Anglo-Saxon glass

Anglo-Saxon glass has been found across England during archaeological excavations of both settlement and cemetery sites. Glass in the Anglo-Saxon period was used in the manufacture of a range of objects including vessels, beads, windows and was even used in jewellery.[1] In the 5th century AD with the Roman departure from Britain, there were also considerable changes in the usage of glass.[2] Excavation of Romano-British sites have revealed plentiful amounts of glass but, in contrast, the amount recovered from 5th century and later Anglo-Saxon sites is minuscule.[2]

The majority of complete vessels and assemblages of beads come from the excavations of early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, but a change in burial rites in the late 7th century affected the recovery of glass, as Christian Anglo-Saxons were buried with fewer grave goods, and glass is rarely found. From the late 7th century onwards, window glass is found more frequently. This is directly related to the introduction of Christianity and the construction of churches and monasteries.[2][3] There are a few Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical[4] literary sources that mention the production and use of glass, although these relate to window glass used in ecclesiastical buildings.[2][3][5] Glass was also used by the Anglo-Saxons in their jewellery, both as enamel or as cut glass insets.[6][7]

Glass vessels

The vast majority of complete vessels come from early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, allowing similar glass vessel to be grouped together creating typologies. More recent excavations of contemporary settlements have revealed fragments of similar vessels types, indicating there are few, if any, differences between domestic glass and those ritually deposited in graves.[5] There is a significant difference between Roman and Anglo-Saxon vessel forms, and glass working techniques became more limited. Few of the Anglo-Saxon forms can be classified as tableware, as this term implies to some extent that vessels can be set on a flat surface. The forms used had primarily rounded or pointed bases, or when bases were present would have been too top heavy and unstable. This implies that vessels were held in the hand until the drink was completed.[2] The evidence for glass vessels is patchier in the 8th century, as the number of complete vessels found decreases. This is directly related to the introduction of Christianity and the change in burial rite.[5][8]

.jpg.webp)

The first typology for Anglo-Saxon glass vessels was devised by Dr. Donald B. Harden in 1956,[8] which was later revised in 1978.[5] The names established by Harden have now become familiar with usage, and Professor Vera Evison’s typology retained many categories while adding some new types, some from newly excavated vessels that could not be placed into Harden’s typology.[2]

| Bowls: Wide vessel often with a flat base. Variety of decoration used including mould blown examples. | Cone Beaker: Tall, tapering vessel with a pointed or curved base. | ||

| Stemmed and Bell Beakers: Bell beakers have a distinctive concave curve to a central pointed base. The stemmed beakers are similar but have a flat foot attached to the central point. | Claw Beaker: Developed from a delicate cup with applied dolphins, in the Anglo-Saxon period these were thicker vessels with plainer, more claw like appliqués. | ||

| Bottles: Rare in Anglo-Saxon England compared to on the continent, in the Rhineland and Northern France. | Palm Cups and Funnel Beakers: Palm cups are bowl shaped but have a curved base. Funnel beakers are funnel shaped with a pointed base. | ||

| Globular Beaker: These were the most common vessels found in the 6th-7th century. Previously known as squat jugs by Harden they are narrow-necked vessels with everted rims, globular bodies and pushed in base. Often occur in pairs. | Pouch Bottles: Unstable, rounded based vessel, form and decoration like the globular beaker although often taller. | ||

| Bag Beaker: More cylindrical form of the globular beaker, with a rounded or pointed base. | Horn: Drinking horn shaped vessel. | ||

| Inkwell: Fragments of inkwells have been discovered in 8th century contexts and indicate a small cylindrical vessel with narrow central opening at the top. | Cylindrical Jar: A few fragments from cylindrical jars have been discovered. |

The chemical composition of Anglo-Saxon glass vessels is very similar to late Roman glass, which has high amounts of iron, manganese and titanium. The slightly higher amounts of iron in the Early Anglo-Saxon glass results in a colourless glass, with a green-yellow tinge. By the end of the 7th century some innovations can be observed. With generally better quality glass, a greater range of colours found and the beginning of the tendency to use a second colour for decoration. Most Anglo-Saxon vessels were free blown, although occasionally some mould blown examples are found, mostly with vertical ribbing. The rims were fire rounded, sometimes slightly thickened and cupped, rolled or folded either inwards or outwards. Decoration was accomplished almost entirely by the application of trails which could be in the same colour as the vessel or contrasting, or in the form of a reticella[9] like trail.[2][5]

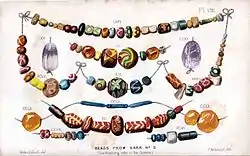

Glass beads

The vast majority of early Anglo-Saxon female graves contain beads, which are often found in large numbers in the area of the neck and chest. Beads are also sometimes found in male burials, with large beads often associated with prestigious weapons. A variety of materials other than glass were available for Anglo-Saxon beads including; amber, rock crystal, amethyst, bone, shells, coral and even metal.[10] These beads are usually considered to have been decorative but may also have a social or ritual function.[11] Anglo-Saxon glass beads show a wide variety of bead manufacturing techniques, sizes, shapes, colours and decorations. Various studies have been carried out investigating the distribution and chronological change of bead types.[12][11]

Several bead manufacturing sites have been identified on the continent, by the presence of waste glass, beads and glass rods. Two late Roman to 5th century sites have been discovered at Trier and Tibiscum in Romania, while closer to England and dating to the 6th-7th century two more sites have been found at Jordenstraat and Rothulfuashem (Netherlands). There is also extensive evidence for bead making workshops in Scandinavia which have been dated to the 8th century or later. The best known examples are Eketorp on Öland (Sweden) and Ribe in Jutland (Denmark).[12][11] There is a tendency for British archaeologists to assume that the majority of glass beads recovered were imported. Although to date there is a lack of direct evidence for bead manufacture in early Anglo-Saxon England, there is evidence for it in early Christian Ireland, northern Britain and the post-Roman west. It is also present on Saxon monastic and settlement sites between the 7th and 9th century. Even so, indirect evidence from the distribution of early Saxon beads has been used to suggest that there is at least three bead groups which were being manufactured in England.[10]

To date only two extensive chemical analysis studies of Anglo-Saxon bead assemblages have been carried out, from the cemeteries of Sewerby in Yorkshire and Apple Down in Sussex. These studies showed that, like glass vessels, the beads had a modified soda-lime-silica composition with high manganese and iron oxide contents. Variations in the composition directly related to the glass colour.[12] Lead rich opaque glass was also prominent in Anglo-Saxon Britain, most likely due to its lower softening temperature and longer working period, which would not melt or distort the bead body.[13] The bead body could be constructed in a number of different ways; winding, drawing, piercing, folding or even a combination of these. Decoration was applied by adding twisting rods of colour, coloured mosaic patterns, enclosing metal between layers of clear glass or simply adding a different colour in either drops or trails.[11][13]

Window glass

With the introduction of Christianity in the early 7th century and the building of ecclesiastical structures the amount of window glass also increased. Window glass, some of which was also coloured, has been identified at more than 17 sites, of which 12 are ecclesiastical. Hundreds of window glass fragments have been found at Jarrow, Wearmouth, Brandon, Whithorn and Winchester.[14][15] This evidence supports the historical records, such as Bede’s account of Benedict Biscop’s importation of glaziers from Gaul to glaze the windows in the monastery at Wearmouth in AD 675.[3][15]

Most Anglo-Saxon window glass is thin, durable, bubbly and when colourless has a pale bluish-green tint. Many of the ecclesiastical sites have also produced strongly coloured glass from the 7th century onwards. Analysis of window glass from Beverley, Uley, Winchester, Whithorn, Wearmouth and Jarrow, has revealed that the majority was again a soda-lime-silica glass but it has also revealed that the composition is different from that of vessel glass, with lower quantities of iron, manganese and titanium suggesting a different source of raw material, possibly from The Levant.[16][15] The analysis also revealed more about the transition from using soda as a flux, to potash.[17][15]

Window glass in antiquity could be produced in three ways; cylinder blown, crown manufacture or cast. In Anglo-Saxon England there is evidence for all three types of methods being used. The vast majority of glass windows were produced by the cylinder blown method, although possibly on a smaller scale than the classic methods mentioned by Theophilus. Some Anglo-Saxon window glass was produced by the crown method and at Repton thick pieces of window glass with swirling layered surfaces were possibly made using the cast method.[15]

Jewellery glass

The majority of jewellery in the 6th-7th century made intensive use of flat, cut almandine garnets in gold and garnet cloisonné (or "cellwork") but occasionally glass was also cut and inset as gems. The colours used were almost entirely limited to blue and green.[6] Occasionally red glass has been used as a substitute for garnet, for example in some of the Sutton Hoo objects, such as the purse-lid and blue glass in the shoulder clasps.[6][7] The 7th-century Forsbrook Pendant also mixes garnet and blue glass inlays. Anglo-Saxon enamel was also used in the production of jewellery, with coloured glass melted in separate cells.[6]

Chemical analysis of this glass has revealed that they are a soda-lime-silica glass but with a lower iron and manganese oxide content than the high iron, manganese and titanium glass used to make vessels. The similarity between the composition of the glass inlays and Roman coloured glass is remarkable, so much so that it is likely that the Anglo-Saxon craftworkers were re-using Roman opaque glass, possibly Roman glass tesserae.[6]

Glass manufacture

Glass making is the production of raw glass from the raw materials.[18], whilst glass working is the processing of raw glass or recycled glass to create new glass objects; this may take place in the same location as glass making or it can take place elsewhere.

Glass making

Glass consists of four principal components; a former, alkali flux, stabiliser and colourants/opacifiers.

- Former: Silica, which in the Roman and Anglo-Saxon period was added in the form of sand.

- Alkali flux: Soda or potash. The Roman sources, in addition to chemical analysis of glass dating to the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods, suggest that mineral natron was used as the flux. Pliny also states that the preferred source of natron for glass making was from Egypt.[16] At the end of the 1st millennium AD a new source of flux was being used, wood ash, which is a source of potash.[17]

- Stabiliser: Lime or magnesia. In Anglo-Saxon glass the main stabiliser was lime. This may have been deliberately added to the glass batch, but may simply have been a component of the sand that was used. Roman writer Pliny stated that sand from the River Belus was particularly suitable for glass-making,[19] this is a calcareous sand, rich in marine shells, and therefore lime.[16][20]

- Colourants/Opacifiers: These can be naturally present in the glass due to impurities in the raw materials, e.g. in the case of green/blue-green glass which results from the presence of iron in the sand. Other colourants are likely to be deliberate additions to the glass melt of small quantities of mineral-rich material[12][11] or in some cases slags from metalworking processes.[21] The elements in ancient glass that affect its appearance are mainly iron, manganese, cobalt, copper, tin and antimony. The presence or absence of lead is also important, while it doesn’t produce a colour itself (except in the form lead-tin oxide or lead-antimony oxide) it can change the hue of other colourants. In addition when added to opaque glasses it ensures that the colourants form in a controlled way and are uniformly distributed. Opacity in glass can be due to a number of factors; intensity of colour, bubbles in the glass or the inclusion of opacifying agents, such as tin (SnO2 & PbSnO3) and antimony (Ca2Sb2O7 & CaSb2O6 & Pb2Sb2O7).[12][11]

The main type of glass found in the Anglo-Saxon period is a soda-lime-silica glass, continuing the Roman tradition of producing glass.[2][3] There is very little evidence for glass making from the raw materials in Roman Britain[20] and even less evidence in Anglo-Saxon Britain.[3] It would have been nearly impossible to transport the natron from the Middle East to Britain. It is therefore far more likely, that as in the Roman period, glass was being produced near the raw materials and then lumps of raw glass transported. Another source of glass was cullet, recycled broken or crushed glass. Recycling was carried out throughout the Roman period,[20] and large deposits of broken glass at Winchester and Hamwic suggest glass was also being recycled in the Anglo-Saxon period.[3][22] It is possible that by recycling glass in this way it was possible to keep up to the demand for glass products without new raw glass having to be introduced into the system. Additional cullet may also have been collected from the ruins of abandoned Romano-British sites.[3] In the late 7-8th century with the construction of many ecclesiastical establishments and large windows, the demand for glass grew.[17] At this time political problems in the Delta-Wadi Natrun region caused a shortage of natron in the Middle East where the raw glass was produced.[23] This possibly led to glass makers experimenting with new fluxes, which finally led to the introduction of wood ash glasses using potash as the main alkali flux, which was more readily available.[17]

| Site | Date | Na2O | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binchester | 1st | 21.2 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 64.5 | 0.7 | 8 | <0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Castleford | 1st | 16.8 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 69.3 | 0.6 | 6.6 | <0.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| Wroxeter | 1st | 20.3 | 0.6 | 3.2 | 65.4 | 1.1 | 8 | <0.1 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Cadbury Congresbury | 5-6th | 20.1 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 62.8 | 0.7 | 9.3 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| Spong Hill | 5-6th | 18.5 | 0.7 | 3.8 | 65.9 | 1.1 | 7.1 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| Winchester | 5-9th | 16.3 | 0.9 | 4.6 | 67.6 | 1.0 | 7.2 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Repton | 7-8th | 19.6 | 0.7 | 3.4 | 64.6 | 0.9 | 7.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Dorestadt (Netherlands) | 8-9th | 14.9 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 64.7 | 1.1 | 10.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Helgö (Sweden) | 8-9th | 17.3 | 1.1 | 3.8 | 65.6 | 0.9 | 8.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 |

| Hamwic | 8-9th | 13.2 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 70.4 | 1.1 | 7.9 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Lincoln | 9-11th | 13.8 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 69.5 | 0.9 | 9.1 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Roman, Leicester | 1st-3rd | 18.4 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 70.7 | 0.7 | 6.4 | nm | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| HIMT, Carthage | 4-6th | 18.7 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 64.8 | 0.4 | 5.2 | nm | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| Levantine I, Appollonia | 6-7th | 15.2 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 70.6 | 0.7 | 8.1 | nm | <0.1 | 0.4 |

| Levantine II, Bet Eli'ezer | 6-8th | 12.1 | 0.6 | 3.3 | 74.9 | 0.5 | 7.2 | nm | <0.1 | 0.5 |

| Egypt II, Ashmenein | 8-9th | 15.0 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 68.2 | 0.2 | 10.8 | nm | 0.2 | 0.7 |

Table above: Compositions of glass from the 1st Millennium AD. Adapted from data published in Sanderson, Hunter and Warren’s analysis[24] of 1st Millennium AD glass (top) and data published by Freestone’s study of the provenance of ancient glass through compositional analysis (bottom).[16] HIMT stands for high iron, manganese and titanium glass, nm for not measured and where there were only traces or the value was below the analytical equipment's detection limits <0.1 is used.

Glass working

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon society and culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

| Power and organization |

| Religion |

Excavation of Anglo-Saxon sites has produced some evidence for limited glass working in the form of crucibles for melting glass, glass debris and furnaces, although, to date, no furnaces have been found associated with crucibles or glass working debris, or vice versa. All the glass working furnaces that have been found are associated with ecclesiastical sites such as monasteries. This gives the impression that these centres sponsored the majority of glass working in Anglo-Saxon Britain, presumably to primarily work on making glass windows for the church buildings. Documentary sources suggest glass workers were itinerant travelling around the country, producing glass on demand, possibly re-using broken glass, rather than there being a single centre producing worked glass objects which would then need to be transported.[1][3]

Although we can identify the production processes it is still not known how much glass working took place in the Anglo-Saxon period and how widespread it was. The absence of evidence has often been used to argue that the majority of glass was imported from the continent. But this seems unlikely as there are limited numbers of glass vessel manufacturing sites found elsewhere in Europe and some of the Anglo-Saxon glass vessels are unique to England, suggesting the presence of some manufacture centres, possibly in Kent.[2][8] Instead the number of glass working sites reflects not only the nature of the fragmented Anglo-Saxon archaeological record but also the nature of glass, which could be melted down and re-used.[1][20]

See also

- Anglo-Saxon art

- Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon culture and people.

- Forest glass

Notes

- Bayley. Glass-working in Early Medieval England. In Price 2000: 137–142.

- Evison. Glass vessels in England, AD 400-1100. In Price 2000: 47–104.

- Heyworth 1992

- Ecclesiastical: Of or relating to a church or to an established religion.

- Harden 1978

- Bimson and Freestone. Analysis of some glass from Anglo-Saxon Jewellery. In Price 2000: 137–142.

- Bimson 1978.

- Harden 1956.

- The term reticella is often used incorrectly to describe fine twists and cables, often in a herringbone design and generally in two colours. The term is only correctly applicable to a particular technique used to decorate glass vessels by Venetian glassworkers.

- Guido and Welch. Indirect evidence for glass bead manufacture in early Anglo-Saxon England. In Price 2000 115–120.

- Brugmann 2004

- Guido and Welch 1999

- Hirst. An approach to the study of Anglo-Saxon glass beads. In J. Price 2000 121–130.

- Cramp 1975

- Cramp. Anglo-Saxon Window Glass. In Price 2000: 105–114.

- Freestone 2005

- Henderson 1992

- Biek and Bayley 1979

- Eichholz 1989

- Price and Cool 1991

- Heck and Hoffmann 2002

- Hunter and Heyworth 1998

- Shortland et al. 2006

- Sanderson et al. 1984

References

- Biek, L. & J. Bayley 1979. Glass and other vitreous materials. World archaeology 11:1-25.

- Bimson, M. 1978. Coloured glass and millefiori in the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. In Annales du 7e congrès international d'etude historique du verre: Berlin, Leipzig, 15-21 aout 1977: Liège: Editions du Secretariat Général.

- Bimson and Freestone. Analysis of some glass from Anglo-Saxon Jewellery. In Price 2000: 137–142.

- Brugmann, B. 2004. Glass beads from Anglo-Saxon graves: a study of the provenance and chronology of glass beads from early Anglo-Saxon graves, based on visual examination. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Cramp, R. J. 1975. Window glass from the monastic site of Jarrow: Problems of interpretation. Journal of Glass Studies 17:88-96.

- Cramp, R. J. 2000. Anglo-Saxon Window Glass. In J. Price (ed.) Glass in Britain and Ireland AD 350-1100: 105-114. London: British Museum Occasional paper 127.

- Eichholz, D. E. 1989. Natural history: Pliny Vol.10, Libri XXXVI-XXXVII. London: Heinemann.

- Freestone, I. C. 2005. The provenance of ancient glass through compositional analysis. Materials Research Society Symposium Proceedings 852:1-14.

- Guido, M. & M. Welch 1999. The glass beads of Anglo-Saxon England c. AD 400-700: a preliminary visual classification of the more definitive and diagnostic types. Rochester: Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiqaries of London 56.

- Harden, D. B. 1956. Glass Vessels in Britain and Ireland, A.D. 400-1000. In D. B. Harden (ed.) Dark-age Britain: studies presented to E. T. Leeds with a bibliography of his works: London: Methuen.

- Harden, D. B. 1978. Anglo-Saxon and later Medieval glass in Britain: Some recent developments. Medieval Archaeology 22:1-24.

- Heck, M. & P. Hoffmann 2002. Analysis of Early Medieval Glass Beads: The raw materials to produce green, orange and brown colours. Microchimica Acta 139:71-76.

- Henderson, J. 1992. Early medieval glass technology: the calm before the storm. In S. Jennings and A. Vince (eds) Medieval Europe 1992: Volume 3 Technology and Innovation: 175-180. York: Medieval Europe 1992.

- Heyworth, M. 1992. Evidence for early medieval glass-working in north-western Europe. In S. Jennings and A. Vince (eds) Medieval Europe 1992: Volume 3 Technology and Innovation: 169-174. York: Medieval Europe 1992.

- Hunter, J. R. & M. P. Heyworth 1998. The Hamwic glass. York: Council for British Archaeology.

- Price, J. & H. E. M. Cool 1991. The evidence for the production of glass in Roman Britain. In D. Foy and G. Sennequier (eds) Ateliers de verriers de l'antiquité à la période pré-industrielle: 23-30. Rouen: Association Française pour l'Archéologie du Verre.

- Price, J. 2000. Glass in Britain and Ireland AD 350-1100. London: British Museum Occasional paper 127.

- Sanderson, D. C., J. R. Hunter & S. E. Warren 1984. Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence Analysis of 1st Millennium AD Glass from Britain. Journal of Archaeological Science 11:53-69.

- Shortland, A., L. Schachner, I. C. Freestone & M. S. Tite 2006. Natron as a flux in the early vitreous materials industry: sources, beginnings and reasons for decline. Journal of Archaeological Science 33:521-530.

External links

- Anglo-Saxon, Viking, Norman and British Living History 950-1066AD. Glass and Amber

- Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Glass in the British Museum, Vera I. Evison et al., 2008, text online

- Museum of London, Anglo-Saxon glass finds