Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England

In the seventh century the pagan Anglo-Saxons were converted to Christianity (Old English: Crīstendōm) mainly by missionaries sent from Rome. Irish missionaries from Iona, who were proponents of Celtic Christianity, were influential in the conversion of Northumbria, but after the Synod of Whitby in 664, the Anglo-Saxon church gave its allegiance to the Pope.

| This article is part of the series: |

| Anglo-Saxon society and culture |

|---|

|

| People |

| Language |

| Material culture |

| Power and organization |

| Religion |

Background

Christianity in Roman Britain dates to at least the 3rd century. It was introduced by tradesmen, immigrants, and legionaries.[1] In 314, three bishops from Britain attended the Council of Arles. They were Eborius from the city of Eboracum (York), Restitutus from the city of Londinium (London), and Adelfius (the location of his see is uncertain). The presence of these three bishops indicates that by the early 4th century, the British church was already organised on a regional basis and had a distinct episcopal hierarchy.[2] It is unclear how widely the Romano-British people adopted Christianity. Archaeological evidence from Roman villas indicates that some aristocrats were Christians, but there is little evidence for the existence of urban churches.[3]

Roman rule ended in the 5th century, and Romano-British society collapsed. Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain began during the same period.[4] The Anglo-Saxons were a mix of invaders, migrants, and acculturated indigenous people. Before the withdrawal of the Romans, Germanic militia had been stationed in Britain as foederati. After the departure of the Roman army, the Britons recruited the Anglo-Saxons to defend Britain, but they rebelled against their British hosts in 442.[5] The newcomers eventually conquered England, and their religion, Anglo-Saxon paganism, became dominant. The Britons of Wales and Cornwall, however, continued to practice Christianity.[6]

Kent

At the end of the 6th century the most powerful ruler among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was Æthelberht of Kent, whose lands extended north to the River Humber. He married a Frankish princess, Bertha of Paris, daughter of Charibert I and his wife Ingoberga. There were strong trade connections between Kent and the Franks. The marriage was agreed to on the condition that she be allowed to practice her religion.[7] She brought her chaplain, Liudhard, with her. A former Roman church was restored for Bertha just outside the City of Canterbury. Dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours, it served as her private chapel.

Gregorian mission

In 595, Pope Gregory I dispatched Augustine, prior of Gregory's own monastery of St Andrew in Rome, to head the mission to Kent.[8] Augustine arrived on the Isle of Thanet in 597 and established his base at the main town of Canterbury.[9] Æthelberht converted to Christianity sometime before 601; other conversions then followed. The following year, he established the Monastery of SS. Peter and Paul. After Augustine's death in 604, the monastery was named after him and eventually became a missionary school.[10]

Through the influence of Æthelberht, his nephew Sæberht of Essex also converted, as did Rædwald of East Anglia, although Rædwald also retained an altar to the old gods.[11] In 601 Pope Gregory sent additional missioners to assist Augustine. Among them was the monk Mellitus. Gregory wrote the Epistola ad Mellitum advising him that local temples be Christianized and asked Augustine to Christianize pagan practices, so far as possible, into dedication ceremonies or feasts of martyrs in order to ease the transition to Christianity. In 604 Augustine consecrated Mellitus as Bishop of the East Saxons. He established his see at London at a church probably founded by Æthelberht, rather than Sæberht.[12] Another of Augustine's associates was Justus for whom Æthelberht built a church near Rochester, Kent. Upon Augustine's death around 604, he was succeeded as archbishop by Laurence of Canterbury, a member of the original mission.[13]

The North

After the departure of the Romans, the church in Britain continued in isolation from that on the continent and developed some differences in approach. Their version of tradition is often called "Celtic Christianity". It tended to be more monastic-centered than the Roman, which favored a diocesan administration, and differed on the style of tonsure, and dating of Easter. The southern and east coasts were the areas settled first and in greatest numbers by the settlers and so were the earliest to pass from Romano-British to Anglo-Saxon control. The British clergy continued to remain active in the north and west. After meeting with Augustine, around 603, the British bishops refused to recognize him as their archbishop.[14] His successor, Laurence of Canterbury, said Bishop Dagán had refused to either share a roof with the Roman missionaries or to eat with them.[15] There is no indication that the British clergy made any attempts to convert the Anglo-Saxons.

| General |

|---|

| Early |

| Medieval |

| Early Modern |

| Eighteenth century to present |

When Æthelfrith of Bernicia seized the neighboring kingdom of Deira, Edwin, son of Ælla of Deira fled into exile. Around 616, at the Battle of Chester, Æthelfrith ordered his forces to attack a body of monks from the Abbey of Bangor-on-Dee, "If then they cry to their God against us, in truth, though they do not bear arms, yet they fight against us, because they oppose us by their prayers."[16] Shortly after, Æthelfrith was killed in battle against Edwin, who with the support of Rædwald of East Anglia claimed the throne. Edwin married the Christian Æthelburh of Kent, daughter of Æthelberht, and sister of King Eadbald of Kent. A condition of their marriage was that she be allowed to continue the practice of her religion. When Æthelburh traveled north to Edwin's court, she was accompanied by the missioner Paulinus of York. Edwin eventually became a Christian, as did members of his court. When Edwin was killed in 633 at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, Æthelburh and her children returned to her brother's court in Kent, along with Paulinus. James the Deacon remained behind to serve as a missioner in the kingdom of Lindsey, but Bernicia and Deira reverted to heathenism.

Insular missions

The introduction of Christianity to Ireland dates to sometime before the 5th century, presumably in interactions with Roman Britain. In 431, Pope Celestine I consecrated Palladius a bishop and sent him to Ireland to minister to the "Scots believing in Christ".[17] Monks from Ireland, such as Finnian of Clonard, studied in Britain at the monastery of Cadoc the Wise, at Llancarfan and other places. Later, as monastic institutions were founded in Ireland, monks from Britain, such as Ecgberht of Ripon and Chad of Mercia, went to Ireland. In 563 Columba arrived in Dál Riata from his homeland of Ireland and was granted land on Iona. This became the centre of his evangelising mission to the Picts.

When Æthelfrith of Northumbria was killed in battle against Edwin and Rædwald at the River Idle in 616, his sons fled into exile. Some of that time was spent in the kingdom of Dál Riata, where Oswald of Northumbria became Christian. At the death of Edwin's successors at the hand of Cadwallon ap Cadfan of Gwynedd, Oswald returned from exile and laid claim to the throne. He defeated the combined forces of Cadwallon and Penda of Mercia at the Battle of Heavenfield. In 634, Oswald, who had spent time in exile at Iona, asked abbot Ségéne mac Fiachnaí to send missioners to Northumbria. At first, a bishop named Cormán was sent, but he alienated many people by his harshness, and returned in failure to Iona reporting that the Northumbrians were too stubborn to be converted. Aidan criticised Cormán's methods and was soon sent as his replacement.[18] Oswald gave Aidan the island of Lindisfarne, near the royal court at Bamburgh Castle. Since Oswald was fluent in both one of the and Irish, he often served as interpreter for Aidan. Aidan built churches, monasteries and schools throughout Northumbria. Lindisfarne became an important centre of Insular Christianity under Aidan, Cuthbert, Eadfrith and Eadberht. Cuthbert's tomb became a center for pilgrimage.

Monastic foundations

Around 630 Eanswith, daughter of Eadbald of Kent, founded Folkestone Priory.[19]

William of Malmesbury says Rædwald had a step-son, Sigeberht of East Anglia, who spent some time in exile in Gaul, where he became a Christian.[20] After his step-brother Eorpwald was killed, Sigeberht returned and became ruler of the East Angles. Sigeberht's conversion may have been a factor in his achieving royal power, since at that time Edwin of Northumbria and Eadbald of Kent were Christian. Around 631, Felix of Burgundy arrived in Canterbury and Archbishop Honorius sent him to Sigeberht. Alban Butler says Sigeberht met Felix during his time in Gaul and was behind Felix's coming to Anglo-Saxon England.[21] Felix established his episcopal see at Dommoc and a monastery at Soham Abbey. Although Felix's early training may have been influenced by the Irish tradition of Luxeuil Abbey, his loyalty to Canterbury ensured that the church in East Anglia adhered to Roman norms.[22] Around 633, Sigeberht welcomed from Ireland, Fursey and his brothers Foillan and Ultan and gave them land to establish an abbey at Cnobheresburg. Felix and Fursey effected a number of conversions and established many churches in Sigeberht's kingdom. Around the same time Sigeberht established a monastery at Beodricesworth.

Hilda of Whitby was the grand-niece of Edwin of Northumbria. In 627 Edwin and his household were baptized Christian. When Edwin was killed in the Battle of Hatfield Chase, the widowed Queen Æthelburh, her children, and Hilda returned to Kent, now ruled by Æthelburh's brother, Eadbald of Kent. Æthelburh established Lyminge Abbey, one of the first religious houses to be founded in the new Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. It was a double monastery, built on Roman ruins. Æthelburh was the first abbess. It is assumed that Hilda remained with the Queen-Abbess. Nothing further is known of Hild until around 647 when having decided not to join her older sister Hereswith at Chelles Abbey in Gaul, Hild returned north. (Chelles had been founded by Bathild, the Anglo-Saxon queen consort of Clovis II.) Hild settled on a small parcel of land near the mouth of the river Ware, where under the direction of Aidan of Lindisfarne, she took up religious life. In 649, he appointed her abbess of the double monastery of Hartlepool Abbey, previously founded by the Irish recluse Hieu.[23] In 655, in thanksgiving for his victory over Penda of Mercia at the Battle of the Winwæd, King Oswiu brought his year old daughter Ælfflæd to his kinswoman Hilda to be brought up at the abbey.[24] (Hild was the grand-niece of Edwin of Northumbria; Oswiu was the son of Edwin's sister Acha.) Two years later, Oswiu established a double monastery at Streoneshalh, (later known as Whitby), and appointed Hild abbess. Ælfflæd then grew up there. The abbey became the leading royal nunnery of the kingdom of Deira, a centre of learning, and burial-place of the royal family.

Resolving blood feuds

Eormenred of Kent was the son of King Eadbald and grandson of King Æthelberht of Kent. Upon the death of his father, his brother Eorcenberht became king. The description of Eormenred as king may indicate that he ruled jointly with his brother or, alternatively, that as sub-king in a particular area. Upon his death, his two young sons were entrusted to the care of their uncle King Eorcenberht, who was succeeded upon his death by his son Ecgberht. Through the connivance of King Ecgberht's advisor Thunor, the sons of Eormenred were murdered. The king was viewed as having either acquiesced or given the order.[25] In order to quench the family feud which this kinslaying would have provoked, Ecgberht agreed to pay a weregild for the murdered princelings to their sister. (Weregild was an important legal mechanism in early Germanic society; the other common form of legal reparation at this time was blood revenge. The payment was typically made to the family or to the clan.) The legend claims that Domne Eafe was offered (or requested) as much land as her pet hind could run around in a single lap. The result, whether miraculous or by the owner's guidance, was that she gained some eighty sulungs of land on Thanet as weregild, on which to establish the double monastery of St. Mildred's at Minster-in-Thanet.[19] (cf. the story of St. Brigid's miraculous cloak).

A similar situation arose in the North. Eanflæd was the daughter of King Edwin of Northumbria. Her maternal grandfather was King Æthelberht of Kent. She was married to Oswiu, King of Bernicia. In 651, after seven years of peaceful rule, Oswiu declared war on Oswine, King of neighboring Deira. Oswine, who belonged to the rival Deiran royal family, was Oswiu's maternal second cousin.[26] Oswine refused to engage in battle, instead retreating to Gilling and the home of his friend, Earl Humwald.[27] Humwald betrayed Oswine, delivering him to Oswiu's soldiers by whom Oswine was put to death.[28] In Anglo-Saxon culture, it was assumed that the nearest kinsmen to a murdered person would seek to avenge the death or require some other kind of justice on account of it (such as the payment of weregild). However, Oswine's nearest kinsman was Oswiu's own wife, Eanflæd, also second cousin to Oswine.[29] In compensation for her kinsman's murder, Eanflæd demanded a substantial weregild, which she then used to establish Gilling Abbey.[30] The monastery was staffed in part by the relatives of both of their families, and given the task of offering prayers for both Oswiu's salvation and Oswine's departed soul. By founding the monastery shortly after Oswine's death,[31] Oswiu and Eanflæd avoided the creation of a feud.[32]

Synod of Whitby (664)

By the early 660s, Insular Christianity received from the monks of Iona was standard in the north and west, while the Roman tradition brought by Augustine was the practice in the south. In the Northumbrian court King Oswiu followed the tradition of the missionary monks from Iona, while Queen Eanflæd, who had been brought up in Kent followed the Roman tradition. The result was that one portion of the court would be celebrating Easter, while the other was still observing the Lenten fast.

At that time, Kent, Essex, and East Anglia were following Roman practice. Oswiu's eldest son, Alhfrith, son of Rhiainfellt of Rheged, seems to have supported the Roman position. Cenwalh of Wessex recommended Wilfrid, a Northumbrian churchman who had recently returned from Rome,[33] to Alhfrith as a cleric well-versed in Roman customs and liturgy.[34] Alhfrith gave Wilfrid a monastery he had recently founded at Ripon, with Eata, abbot of Melrose Abbey and former student of Aidan of Lindisfarne.[35] Wilfrid ejected Abbot Eata, because he would not conform to Roman customs; and Eata returned to Melrose.[34] Cuthbert, the guest-master was also expelled.[36] Wilfrid introduced a form of the Rule of Saint Benedict into Ripon.

In 664, King Oswiu convened a meeting at Hild's monastery to discuss the matter. The Celtic party was led by Abbess Hilda, and bishops Colmán of Lindisfarne and Cedd of Læstingau. (In 653, upon the occasion of the marriage of Oswiu's daughter Alchflaed with Peada of Mercia, Oswiu had sent Cedd to evangelize the Middle Angles of Mercia.) The Roman party was led by Wilfrid and Agilbert.

The meeting did not proceed entirely smoothly due to variety of languages spoken, which probably included Old Irish, Old English, Frankish and Old Welsh, as well as Latin. Bede recounted that Cedd interpreted for both sides.[37] Cedd's facility with the languages, together with his status as a trusted royal emissary, likely made him a key figure in the negotiations. His skills were seen as an eschatological sign of the presence of the Holy Spirit, in contrast to the Biblical account of the Tower of Babel.[38] Colman appealed to the practice of St. John; Wilfrid to St. Peter. Oswiu decided to follow Roman rather than Celtic rite, saying ""I dare not longer contradict the decrees of him who keeps the doors of the Kingdom of Heaven, lest he should refuse me admission".[39] Some time after the conference Colman resigned the see of Lindisfarne and returned to Ireland.

Anglo-Saxon saints

A number of Anglo-Saxon saints are connected to royalty.[40] King Æthelberht of Kent and his wife Queen Bertha were later regarded as saints for their role in establishing Christianity among the Anglo-Saxons. Their granddaughter Eanswith founded Folkestone Priory, in 630 the first monastery in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms for women.[41] Her aunt Æthelburh founded Lyminge Abbey about four miles northwest of Folkestone on the south coast of Kent around 634. In a number of instances, the individual retired from court to take up the religious life. The sisters Mildrith, Mildburh, and Mildgyth, great granddaughters of King Æthelberht and Queen Bertha, and all abbesses at various convents, were revered as saints. Ceolwulf of Northumbria abdicated his throne and entered the monastery at Lindisfarne.[42]

In some cases, where the death of a member of royalty appears to be largely politically motivated, it was viewed as martyrdom due to the circumstances. The murdered princes Æthelred and Æthelberht were later commemorated as saints and martyrs. Oswine of Deira was betrayed by a trusted friend to soldiers of his enemy and kinsman Oswiu of Bernicia. Bede described Oswine as "most generous to all men and above all things humble; tall of stature and of graceful bearing, with pleasant manner and engaging address".[43] Likewise, the sons of Arwald of the Isle of Wight were betrayed to Cædwalla of Wessex, but because they were converted and baptized by Abbot Cynibert of Hreutford immediately before being executed, they were considered saints.[44] Edward the Martyr was stabbed to death on a visit to his stepmother Queen Ælfthryth and his stepbrother, the boy Æthelred while dismounting from his horse, although there is no indication that he was particularly noted for virtue.

Royalty could use their affiliation to such cults in order to claim legitimacy against competitors to the throne.[45] A dynasty may have had accrued prestige for having a saint in its family.[46] Promoting a particular cult may have aided a royal family in claiming political dominance over an area, particularly if that area was recently conquered.[46]

Anglo-Saxon mission on the Continent

In 644, the twenty-five year old Ecgberht of Ripon was a student at the monastery of Rath Melsigi when he and many others fell ill of the plague. He vowed that if he recovered, he would become a perpetual pilgrimage from his homeland of Britain and would lead a life of penitential prayer and fasting.[47] He began to organize a mission to the Frisians, but was dissuaded from going by a vision related to him by a monk who had been a disciple of Saint Boisil, prior of Melrose. Ecgberht then recruited others.

Around 677, Wilfrid, bishop of York quarreled with King Ecgfrith of Northumbria and was expelled from his see. Wilfrid went to Rome to appeal Ecgfrith's decision.[48] On the way he stopped in Utrecht at the court of Aldgisl, the rulers of the Frisians, for most of 678. Wilfrid may have been blown off course on his trip from Anglo-Saxon lands to the continent, and ended up in Frisia; or he may have intended to journey via Frisia to avoid Neustria, whose Mayor of the Palace, Ebroin, disliked Wilfrid.[36] While Wilfrid was at Aldgisl's court, Ebroin offered a bushel of gold coins in return for Wilfrid, alive or dead. Aldgisl's hospitality to Wilfrid was in defiance of Frankish domination.

The first missioner was Wihtberht who went to Frisia about 680 and labored for two years with the permission of Aldgisl; but being unsuccessful, Wihtberht returned to Briiain.[49] Willibrord grew up under the influence of Wilfrid, studied under Ecgberht of Ripon, and spent twelve years at the Abbey of Rath Melsigi. Around 690, Ecgberht sent him and eleven companions to Christianise the Frisians. In 695 Willibrord was consecrated in Rome, Bishop of Utrecht. In 698 he established the Abbey of Echternach on the site of a Roman villa donated by the Austrasian noblewoman Irmina of Oeren. Aldgisl's successor Redbad was less supportive than his father, likely because the missionaries were favored by Pepin of Herstal, who sought to expand his territory into Frisia.

In 716, Boniface joined Willibrord in Utrecht. Their efforts were frustrated by the war between Charles Martel and Redbad, King of the Frisians. Willibrord fled to the abbey he had founded in Echternach, while Boniface returned to the Benedictine monastery at Nhutscelle. The following year he traveled to Rome, where he was commissioned by Pope Gregory II as a traveling missionary bishop for Germania.

Benedictine reform

The Benedictine reform was led by Saint Dunstan over the latter half of the 10th century. It sought to revive church piety by replacing secular canons- often under the direct influence of local landowners, and often their relatives- with celibate monks, answerable to the ecclesiastical hierarchy and ultimately to the Pope. This deeply split the newly formed kingdom of England, bringing it to the point of civil war, with the East Anglian nobility (such as Athelstan Half-King, Byrhtnoth) supporting Dunstan and the Wessex aristocracy (Ordgar, Æthelmær the Stout) supporting the secularists. These factions mobilised around King Eadwig (anti-Dunstan) and his brother King Edgar (pro). On the death of Edgar, his son Edward the Martyr was assassinated by the anti-Dunstan faction and their candidate, the young king Æthelred was placed on the throne. However this "most terrible deed since the English came from over the sea" provoked such a revulsion that the secularists climbed down, although Dunstan was effectively retired.

This split fatally weakened the country in the face of renewed Viking attacks.

Church organisation

Under papal authority, the English church was divided into two ecclesiastical provinces, each led by a metropolitan or archbishop. In the south, the Province of Canterbury was led by the archbishop of Canterbury. It was originally to be based at London, but Augustine and his successors remained at Canterbury instead. In the north, the Province of York was led by the archbishop of York.[50] Theoretically, neither archbishop had precedence over the other. In reality, the south was wealthier than the north, and the result was that Canterbury dominated.[51]

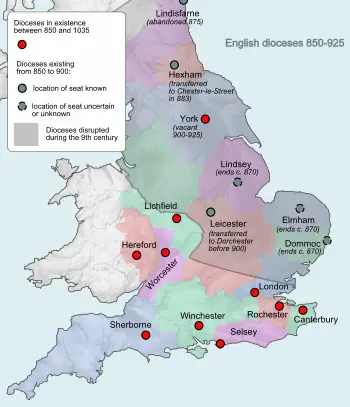

In 669, Theodore of Tarsus became Archbishop of Canterbury. In 672 he convened the Council of Hertford which was attended by a number of bishops from across the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. This Council was a milestone in the organization of the Anglo-Saxon Church, as the decrees passed by its delegates focused on issues of authority and structure within the church.[52] Afterwards Theodore, visiting the whole of Anglo-Saxon held lands, consecrated new bishops and divided up the vast dioceses which in many cases were coextensive with the kingdoms of the heptarchy.[53]

Initially, the diocese was the only administrative unit in the Anglo-Saxon church. The bishop served the diocese from a cathedral town with the help of a group of priests known as the bishop's familia. These priests would baptise, teach and visit the remoter parts of the diocese. Familiae were placed in other important settlements, and these were called minsters.[54]

In the late 10th century, the Benedictine Reform movement helped to restore monasticism in England after the Viking attacks of the 9th century. The most prominent reformers were Archbishop Dunstan of Canterbury (959–988), Bishop Æthelwold of Winchester (963–984), and Archbishop Oswald of York (971–992). The reform movement was supported by King Edgar (r. 959–975). One result of the reforms was the creation of monastic cathedrals at Canterbury, Worcester, Winchester, and Sherborne. These were staffed by cloistered monks, while other cathedrals were staffed by secular clergy called canons. By 1066, there were over 45 monasteries in England, and monks were chosen as bishops more often than in other parts of western Europe.[55]

Most villages would have had a church by 1042,[55] as the parish system developed as an outgrowth of manorialism. The parish church was a private church built and endowed by the lord of the manor, who retained the right to nominate the parish priest. The priest supported himself by farming his glebe and was also entitled to other support from parishioners. The most important was the tithe, the right to collect one-tenth of all produce from land or animals. Originally, the tithe was a voluntary gift, but the church successfully made it a compulsory tax by the 10th century.[56]

By 1000, there were eighteen dioceses in England: Canterbury, Rochester, London, Winchester, Dorchester, Ramsbury, Sherborne, Selsey, Lichfield, Hereford, Worcester, Crediton, Cornwall, Elmham, Lindsey, Wells, York and Durham. To assist bishops in supervising the parishes and monasteries within their dioceses, the office of archdeacon was created. Once a year, the bishop would summon parish priests to the cathedral for a synod.[57]

Church and state

The church was a wealthy institution—owning 25 to 33 per cent of all land according to the Domesday Book. This meant that bishops and abbots had the same status as secular magnates, and it was vital that kings appointed loyal men to these influential offices.[58]

The king was regarded not only as the head of the church but also "the vicar of Christ among a Christian folk".[59] Kings were able to "govern the church largely unimpeded" by appointing bishops and abbots.[58] Bishops were chosen by the king and tended to be recruited from among royal chaplains or monasteries. The bishop-elect was then presented at a synod where clerical approval was obtained and consecration followed. The appointment of an archbishop was more complicated and required approval from the pope. The Archbishop of Canterbury had to travel to Rome to receive the pallium, his symbol of office. These visits to Rome and the payments that accompanied them (such as Peter's Pence) was a point of contention.[60]

References

- DiMaio, Michael Jr. (February 23, 1997). "Licinius (308–324 A.D.)". De Imperatoribus Romanis.

- Petts 2003, p. 39.

- Morris 2021, p. 36.

- Morris 2021, pp. 22 & 30.

- Myres 1989, p. 104.

- Morris 2021, pp. 35–36 & 39.

- Wace, Henry and Piercy, William C., "Bertha, wife of Ethelbert, king of Kent", Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the sixth Century, Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. ISBN 1-56563-460-8

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Lyle, Marjorie (2002), Canterbury: 2000 Years of History, Tempus, ISBN 978-0-7524-1948-0 p. 48

- Maclear, G.F., S. Augustine's, Canterbury: Its Rise, Ruin, and Restoration, London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co., 1888

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Plunkett, Steven (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0 p. 75

- Brooks, N. P. (2004). "Mellitus (d. 624)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2005 revised ed.). Oxford University Press

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09086-5 p. 37

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 71 ISBN 0-271-00769-9

- Stenton 1971, p. 112.

- Alston, George Cyprian. "St. Dinooth." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 21 April 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Cusack, Margaret Anne, "Mission of St. Palladius", An Illustrated History of Ireland, Chapter VIII

- Kiefer, James E., "Aidan of Lindisfarne, Missionary", Biographical Sketches of memorable Christians of the past", Society of Archbishop Justus. 29 August 1999

- Alston, George Cyprian. "The Benedictine Order." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 25 April 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - William of Malmesbury. Chronicle of the Kings of England, London, George Bell and Son, 1904. p. 89

- Butler, Alban. “Saint Felix, Bishop and Confessor”. Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Principal Saints, 1866. CatholicSaints.Info. 7 March 2013

- Stenton 1971, p. 117.

- "Hilda of Whitby", Society for the Study of Women Philosophers

- "An Anglo-Saxon Monastery at Hartlepool", Tees Archaeology

- Wasyliw, Patricia Healy. Martyrdom, Murder, and Magic: Child Saints and Their Cults in Medieval Europe, Peter Lang, 2008, p. 74ISBN 9780820427645

- Yorke, Barbara, Kings and Kingdoms in Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby, 1990, p. 76 ISBN 1-85264-027-8

- Strutt, Joseph (1777). From the Arrival of Julius Caesar to the End of the Saxon Heptarchy. Joseph Cooper. p. 139. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Hutchinson, William (1817). The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham (Volume 1 ed.). p. 9. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge, p. 78 ISBN 978-0-415-24211-0

- Yorke 1990, p. 80.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, p. 106 ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman, p. 234 ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, 3rd edition (London: B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1991) p. 107. ISBN 9780271038513

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. p. 87 ISBN 0-415-24211-8

- Higham, N. J. (1997). The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. p. 42.ISBN 0-7190-4827-3

- Thacker, Alan (2004). "Wilfrid (St Wilfrid) (c.634–709/10)" ((subscription required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29409

- Bede. Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book 3, chapter 25.

- Mayr-Harting 1991, p. 9.

- Thurston, Herbert. "Synod of Whitby." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 23 April 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Rollason, David (1989). Saints and Relics in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 114. ISBN 978-0631165064.

- Yorke, Barbara (2003). Nunneries and the Anglo-Saxon royal houses. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 23. ISBN 0-8264-6040-2.

- Odden, Per Einer. "The Holy Ceolwulf of Northumbria (~ 695-764)", The Roman Catholic Diocese of Oslo, May 26, 2004

- Parker, Anselm. "St. Oswin." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 23 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Stanton, Richard. A Menology of England and Wales, Burns & Oates, (1892)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Rollason 1989, p. 123.

- Rollason 1989, p. 120.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry. "Ecgberht (639–729)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004, accessed 24 Jan 2014

- Stenton 1971, p. 136.

- St. Cuthbert, His Cult and His Community to AD 1200, (Gerald Bonner et al, eds.) Boydell & Brewer, 1989, p. 194 ISBN 9780851156101

- Starkey 2010, pp. 32–33.

- Huscroft 2016, p. 41.

- Catherine Cubitt, Anglo-Saxon Church Councils, c.650-c.850 (London, 1995), p. 62.

- Thurston, Herbert. "The Anglo-Saxon Church." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 23 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Moorman 1973, p. 27.

- Huscroft 2016, p. 42.

- Moorman 1973, p. 28.

- Moorman 1973, p. 48.

- Huscroft 2016, p. 47.

- Moorman 1973, p. 47: Laws of Ethelred II, quoted in F.M. Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 538

- Loyn 2000, p. 4.

Bibliography

- Chaney, William A. (1960) Paganism to Christianity in Anglo-Saxon England .

- Chaney, William A. (1970). The cult of kingship in Anglo-Saxon England: the transition from paganism to Christianity (Manchester University Press)

- Higham, N. J. (2006) (Re-)Reading Bede: the "Ecclesiastical History" in Context. London: Routledge ISBN 978-0-415-35368-7 ; ISBN 0-415-35367-X

- Huscroft, Richard (2016). Ruling England, 1042-1217 (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1138786554.

- Loyn, H. R. (2000). The English church, 940–1154. The Medieval World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317884729.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). London: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-6589-1.

- Moorman, John R. H. (1973). A History of the Church in England (3rd ed.). Morehouse Publishing. ISBN 978-0819214065.

- Morris, Marc (2021). The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England: 400–1066. Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-64313-312-6.

- Myres, J. N. L. (1989). The English Settlements. Oxford History of England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282235-7.

- Petts, David (2003). Christianity in Roman Britain. Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2540-4.

- Starkey, David (2010). Crown and Country: A History of England through the Monarchy. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780007307715.

- Thomas, Charles (1981) Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500, London: Batsford

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 978-1-85264-027-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006) The Conversion of Britain, Harlow: Pearson Education

Further reading

- Beda Venerabilis (1988). A History of the English Church and People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044042-3.

- Blair, John P. (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Blair, Peter Hunter; Blair, Peter D. (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3.

- Brown, Peter G. (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A. D. 200–1000. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-22138-8.

- Campbell, James (1986). "Observations on the Conversion of England". Essays in Anglo-Saxon History. London: Hambledon Press. pp. 69–84. ISBN 978-0-907628-32-3.

- Campbell, James; John, Eric & Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9.

- Church, S. D. (2008). "Paganism in Conversion-age Anglo-Saxon England: The Evidence of Bede's Ecclesiastical History Reconsidered". History. 93 (310): 162–180. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2008.00420.x.

- Coates, Simon (February 1998). "The Construction of Episcopal Sanctity in early Anglo-Saxon England: the Impact of Venantius Fortunatus". Historical Research. 71 (174): 1–13. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00050.

- Colgrave, Bertram (2007). "Introduction". The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great (Paperback reissue of 1968 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31384-1.

- Collins, Roger (1999). Early Medieval Europe: 300–1000 (Second ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21886-7.

- Dales, Douglas (2005). ""Apostles of the English": Anglo-Saxon Perceptions". L'eredità spirituale di Gregorio Magno tra Occidente e Oriente. Il Segno Gabrielli Editori. ISBN 978-88-88163-54-3.

- Deanesly, Margaret; Grosjean, Paul (April 1959). "The Canterbury Edition of the Answers of Pope Gregory I to St Augustine". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 10 (1): 1–49. doi:10.1017/S0022046900061832.

- Demacopoulos, George (Fall 2008). "Gregory the Great and the Pagan Shrines of Kent". Journal of Late Antiquity. 1 (2): 353–369. doi:10.1353/jla.0.0018. S2CID 162301915.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1985). Anglo-Saxon Art: A New Perspective (Cornell University Press 1985 ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9300-3.

- Dodwell, C. R. (1993). The Pictorial Arts of the West: 800–1200. Pellican History of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06493-3.

- Dyson, Gerald P. (2019). Priests and their Books in Late Anglo-Saxon England. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783273669.

- Fletcher, R. A. (1998). The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity. New York: H. Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-2763-1.

- Foley, W. Trent; Higham, Nicholas. J. (2009). "Bede on the Britons". Early Medieval Europe. 17 (2): 154–185. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.2009.00258.x.

- Frend, William H. C. (2003). Martin Carver (ed.). Roman Britain, a Failed Promise. The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe AD 300–1300. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 79–92. ISBN 1-84383-125-2.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- Gameson, Richard and Fiona (2006). "From Augustine to Parker: The Changing Face of the First Archbishop of Canterbury". In Smyth, Alfred P.; Keynes, Simon (eds.). Anglo-Saxons: Studies Presented to Cyril Roy Hart. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 13–38. ISBN 978-1-85182-932-3.

- Herrin, Judith (1989). The Formation of Christendom. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00831-8.

- Higham, N. J. (1997). The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4827-2.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2006). A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons: The Beginnings of the English Nation. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1738-5.

- Kirby, D. P. (1967). The Making of Early England (Reprint ed.). New York: Schocken Books.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5053-4.

- Jones, Putnam Fennell (July 1928). "The Gregorian Mission and English Education". Speculum (fee required). 3 (3): 335–348. doi:10.2307/2847433. JSTOR 2847433. S2CID 162352366.

- Lapidge, Michael (2006). The Anglo-Saxon Library. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926722-4.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). "Laurentius". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lawrence, C. H. (2001). Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages. New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40427-4.

- Markus, R. A. (April 1963). "The Chronology of the Gregorian Mission to England: Bede's Narrative and Gregory's Correspondence". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 14 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1017/S0022046900064356.

- Markus, R. A. (1970). "Gregory the Great and a Papal Missionary Strategy". Studies in Church History 6: The Mission of the Church and the Propagation of the Faith. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 29–38. OCLC 94815.

- Markus, R. A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58430-2.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (2004). "Augustine (St Augustine) (d. 604)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-03-30.(subscription required)

- McGowan, Joseph P. (2008). "An Introduction to the Corpus of Anglo-Latin Literature". In Philip Pulsiano; Elaine Treharne (eds.). A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature (Paperback ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 11–49. ISBN 978-1-4051-7609-5.

- Meens, Rob (1994). "A Background to Augustine's Mission to Anglo-Saxon England". In Lapidge, Michael (ed.). Anglo-Saxon England 23. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–17. ISBN 978-0-521-47200-5.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2006). "Bertha (b. c.565, d. in or after 601)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2008-03-30.(subscription required)

- Ortenberg, Veronica (1965). "The Anglo-Saxon Church and the Papacy". In Lawrence, C. H. (ed.). The English Church and the Papacy in the Middle Ages (1999 reprint ed.). Stroud: Sutton Publishing. pp. 29–62. ISBN 978-0-7509-1947-0.

- Rollason, D.W. (1982). The Mildrith Legend: A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England. Atlantic Highlands: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1201-9.

- Rumble, Alexander R., ed. (2012). Leaders of the Anglo-Saxon Church: From Bede to Stigand. Boydell and Brewer.

- Schapiro, Meyer (1980). "The Decoration of the Leningrad Manuscript of Bede". Selected Papers: Volume 3: Late Antique, Early Christian and Mediaeval Art. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 199 and 212–214. ISBN 978-0-7011-2514-1.

- Sisam, Kenneth (January 1956). "Canterbury, Lichfield, and the Vespasian Psalter". Review of English Studies. New Series. 7 (25): 1–10. doi:10.1093/res/VII.25.1.

- Spiegel, Flora (2007). "The 'tabernacula' of Gregory the Great and the Conversion of Anglo-Saxon England". Anglo-Saxon England 36. Vol. 36. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1017/S0263675107000014. S2CID 162057678.

- "St Augustine Gospels". Grove Dictionary of Art. Art.net. 2000. Accessed on 10 May 2009

- Thacker, Alan (1998). "Memorializing Gregory the Great: The Origin and Transmission of a Papal Cult in the 7th and early 8th centuries". Early Medieval Europe. 7 (1): 59–84. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00018.

- Walsh, Michael J. (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oates. ISBN 978-0-86012-438-2.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 978-0-333-56797-5.

- Wilson, David M. (1984). Anglo-Saxon Art: From the Seventh Century to the Norman Conquest. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 185807396.

- Wood, Ian (January 1994). "The Mission of Augustine of Canterbury to the English". Speculum (fee required). 69 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2864782. JSTOR 2864782. S2CID 161652367.