Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (Italian: Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 1475 – 1 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death, in December 1521.[2]

Leo X | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

.jpg.webp) Detail from Raphael's Portrait of Leo X | |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 9 March 1513 |

| Papacy ended | 1 December 1521 |

| Predecessor | Julius II |

| Successor | Adrian VI |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 15 March 1513 by Raffaele Sansone Riario |

| Consecration | 17 March 1513 by Raffaele Sansone Riario |

| Created cardinal |

by Innocent VIII |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici 11 December 1475 |

| Died | 1 December 1521 (aged 45) Rome, Papal States |

| Buried | Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome |

| Previous post(s) |

|

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

| Other popes named Leo | |

Ordination history of Pope Leo X | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Born into the prominent political and banking Medici family of Florence, Giovanni was the second son of Lorenzo de' Medici, ruler of the Florentine Republic, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1489. Following the death of Pope Julius II, Giovanni was elected pope after securing the backing of the younger members of the Sacred College. Early on in his rule he oversaw the closing sessions of the Fifth Council of the Lateran, but struggled to implement the reforms agreed. In 1517 he led a costly war that succeeded in securing his nephew Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici as Duke of Urbino, but reduced papal finances.

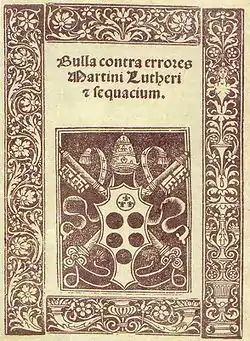

In Protestant circles, Leo is associated with granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica, a practice that was soon challenged by Martin Luther's 95 Theses. Leo rejected the Protestant Reformation, and his Papal bull of 1520, Exsurge Domine, condemned Luther's condemnatory stance, rendering ongoing communication difficult.

He borrowed and spent money without circumspection and was a significant patron of the arts. Under his reign, progress was made on the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica and artists such as Raphael decorated the Vatican rooms. Leo also reorganised the Roman University, and promoted the study of literature, poetry and antiquities. He died in 1521 and is buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome. He was the last pope not to have been in priestly orders at the time of his election to the papacy.

Early life

Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was born on 11 December 1475 in the Republic of Florence, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, head of the Florentine Republic, and Clarice Orsini.[2] From an early age Giovanni was destined for an ecclesiastical career. He received the tonsure at the age of seven and was soon granted rich benefices and preferments.

His father, Lorenzo de' Medici, was worried about his character early on and wrote a letter to Giovanni to warn him to avoid vice and luxury at the beginning of his ecclesiastical career. Here is a notable excerpt: "There is one rule which I would recommend to your attention in preference to all others. Rise early in the morning. This will not only contribute to your health, but will enable you to arrange and expedite the business of the day; and as there are various duties incident to".[3]

Cardinal

His father prevailed on his relative Pope Innocent VIII to name him cardinal of Santa Maria in Domnica on 9 March 1489 when he was age 13,[4] although he was not allowed to wear the insignia or share in the deliberations of the college until three years later. Meanwhile, he received an education at Lorenzo's humanistic court under such men as Angelo Poliziano, Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino and Bernardo Dovizio Bibbiena. From 1489 to 1491 he studied theology and canon law at Pisa.[2]

On 23 March 1492, he was formally admitted into the Sacred College of Cardinals and took up his residence at Rome, receiving a letter of advice from his father. The death of Lorenzo on the following 8 April temporarily recalled the 16-year-old Giovanni to Florence. He returned to Rome to participate in the conclave of 1492 which followed the death of Innocent VIII, and unsuccessfully opposed the election of Cardinal Borgia (elected as Pope Alexander VI).

He subsequently made his home with his elder brother Piero in Florence throughout the agitation of Savonarola and the invasion of Charles VIII of France, until the uprising of the Florentines and the expulsion of the Medici in November 1494. While Piero found refuge at Venice and Urbino, Giovanni traveled in Germany, in the Netherlands, and in France.[5]

In May 1500, he returned to Rome, where he was received with outward cordiality by Pope Alexander VI, and where he lived for several years immersed in art and literature. In 1503 he welcomed the accession of Pope Julius II to the pontificate; the death of Piero de' Medici in the same year made Giovanni head of his family. On 1 October 1511, he was appointed papal legate of Bologna and the Romagna, and when the Florentine republic declared in favour of the schismatic Pisans, Julius II sent Giovanni (as legate) with the papal army venturing against the French. The French won a major battle and captured Giovanni.[6] This and other attempts to regain political control of Florence were frustrated until a bloodless revolution permitted the return of the Medici. Giovanni's younger brother Giuliano was placed at the head of the republic,[7] but Giovanni managed the government.

Pope

Papal election

Giovanni was elected pope on 9 March 1513, and this was proclaimed two days later.[8] The absence of the French cardinals effectively reduced the election to a contest between Giovanni (who had the support of the younger and noble members of the college) and Raffaele Riario (who had the support of the older group). On 15 March 1513, he was ordained priest, and consecrated as bishop on 17 March. He was crowned Pope on 19 March 1513 at the age of 37. He was the last non-priest to be elected pope.[2]

.jpg.webp)

War of Urbino

Leo had intended his younger brother Giuliano and his nephew Lorenzo for brilliant secular careers. He had named them Roman patricians; the latter he had placed in charge of Florence; the former, for whom he planned to carve out a kingdom in central Italy of Parma, Piacenza, Ferrara and Urbino, he had taken with himself to Rome and married to Filiberta of Savoy.[10]

The death of Giuliano in March 1516, however, caused the pope to transfer his ambitions to Lorenzo. At the very time (December 1516) that peace between France, Spain, Venice and the Empire seemed to give some promise of a Christendom united against the Turks, Leo obtained 150,000 ducats towards the expenses of the expedition from Henry VIII of England, in return for which he entered the imperial league of Spain and England against France.[11]

The war lasted from February to September 1517 and ended with the expulsion of the duke and the triumph of Lorenzo; but it revived the policy of Alexander VI, increased brigandage and anarchy in the Papal States, hindered the preparations for a crusade and wrecked the papal finances. Francesco Guicciardini reckoned the cost of the war to Leo at the sum of 800,000 ducats. Ultimately, however, Lorenzo was confirmed as the new duke of Urbino.[11]

Plans for a Crusade

The war of Urbino was further marked by a crisis in the relations between the pope and the cardinals. The sacred college had allegedly grown very worldly and troublesome since the time of Sixtus IV, and Leo took advantage of a plot by several of its members to poison him, not only to inflict exemplary punishments by executing one (Alfonso Petrucci) and imprisoning several others, but also to make radical changes in the college.[11]

On 3 July 1517, he published the names of thirty-one new cardinals, a number almost unprecedented in the history of the papacy. Among the nominations were such notable men such as Lorenzo Campeggio, Giambattista Pallavicini, Adrian of Utrecht, Thomas Cajetan, Cristoforo Numai and Egidio Canisio. The naming of seven members of prominent Roman families, however, reversed the policy of his predecessor which had kept the political factions of the city out of the Curia. Other promotions were for political or family considerations or to secure money for the war against Urbino. The pope was accused of having exaggerated the conspiracy of the cardinals for purposes of financial gain, but most of such accusations appear unsubstantiated.[11]

Leo, meanwhile, felt the need of staying the advance of the Ottoman sultan, Selim I, who was threatening eastern Europe, and made elaborate plans for a crusade. A truce was to be proclaimed throughout Christendom; the pope was to be the arbiter of disputes; the emperor and the king of France were to lead the army; England, Spain and Portugal were to furnish the fleet; and the combined forces were to be directed against Constantinople. Papal diplomacy in the interests of peace failed, however; Cardinal Wolsey made England, not the pope, the arbiter between France and the Empire; and much of the money collected for the crusade from tithes and indulgences was spent in other ways.[11]

In 1519 Hungary concluded a three years' truce with Selim I, but the succeeding sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, renewed the war in June 1521 and on 28 August captured the citadel of Belgrade. The pope was greatly alarmed, and although he was then involved in war with France he sent about 30,000 ducats to the Hungarians. Leo treated the Eastern Catholic Greeks with great loyalty, and by a bull of 18 May 1521 forbade Latin clergy to celebrate mass in Greek churches and Latin bishops to ordain Greek clergy. These provisions were later strengthened by Clement VII and Paul III and went far to settle the constant disputes between the Latins and Uniate Greeks.[11]

Protestant Reformation

Leo was disturbed throughout his pontificate by schism, especially the Reformation sparked by Martin Luther.[11]

In response to concerns about misconduct from some indulgence preachers, in 1517 Martin Luther wrote his Ninety-five Theses on the topic of indulgences. The resulting pamphlet spread Luther's ideas throughout Germany and Europe. Leo failed to fully comprehend the importance of the movement, and in February 1518 he directed the vicar-general of the Augustinians to impose silence on his monks.[11]

On 24 May, Luther sent an explanation of his theses to the pope; on 7 August he was summoned to appear at Rome. An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was cancelled, and Luther went instead to Augsburg in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Cajetan; but neither the arguments of the cardinal, nor Leo's dogmatic papal bull of 9 November requiring all Christians to believe in the pope's power to grant indulgences, moved Luther to retract. A year of fruitless negotiations followed, during which the controversy took popular root across the German states.[11]

A further papal bull of 15 June 1520, Exsurge Domine or Arise, O Lord, condemned forty-one propositions extracted from Luther's teachings, and was taken to Germany by Eck in his capacity as apostolic nuncio. Leo followed by formally excommunicating Luther by the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem or It Befits the Roman Pontiff, on 3 January 1521. In a brief, the Pope also directed Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor to take energetic measures against heresy.[11]

Leo was pope during the spread of Lutheranism into Scandinavia. The pope had repeatedly used the rich northern benefices to reward members of the Roman curia, and towards the close of the year 1516, he sent the impolitic Arcimboldi as papal nuncio to Denmark to collect money for St Peter's. This led to the Reformation in Denmark. King Christian II took advantage of the growing dissatisfaction of the native clergy toward the papal government, and of Arcimboldi's interference in the Swedish revolt, to expel the nuncio and summon Lutheran theologians to Copenhagen in 1520. Christian approved a plan by which a formal state church should be established in Denmark, all appeals to Rome should be abolished, and the king and diet should have final jurisdiction in ecclesiastical causes. Leo sent a new nuncio to Copenhagen (1521) in the person of the Minorite Francesco de Potentia, who readily absolved the king and received the bishopric of Skara. The pope or his legate, however, took no steps to correct abuses or otherwise discipline the Scandinavian churches.[11]

.JPG.webp)

Consistories

The pope created 42 new cardinals in eight consistories including two cousins (one who would become his successor Pope Clement VII) and a nephew. He also elevated Adriaan Florensz Boeyens into the cardinalate who would become his immediate successor Pope Adrian VI. Leo X's consistory of 1 July 1517 saw 31 cardinals created, and this remained the largest allocation of cardinals in one consistory until Pope John Paul II named 42 cardinals in 2001.

Canonizations

Pope Leo X canonized eleven individuals during his reign with seven of those being a group cause of martyrs. The most notable canonization from his papacy was that of Francis of Paola on 1 May 1519.

Final years

That Leo did not do more to check the anti-papal rebellion in Germany and Scandinavia is to be partially explained by the political complications of the time, and by his own preoccupation with papal and Medicean politics in Italy. The death of the emperor Maximilian in 1519 had seriously affected the situation. Leo vacillated between the powerful candidates for the succession, allowing it to appear at first that he favoured Francis or a minor German prince. He finally accepted Charles of Spain as inevitable.[11]

Leo was now eager to unite Ferrara, Parma and Piacenza to the States of the Church (The Papal States). An attempt late in 1519 to seize Ferrara failed, and the pope recognized the need for foreign aid. In May 1521 a treaty of alliance was signed at Rome between him and the emperor. Milan and Genoa were to be taken from France and restored to the Empire, and Parma and Piacenza were to be given to the Church on the expulsion of the French. The expense of enlisting 10,000 Swiss was to be borne equally by Pope and emperor. Charles V took Florence and the Medici family under his protection and promised to punish all enemies of the Catholic faith. Leo agreed to invest Charles V with the Kingdom of Naples, to crown him Holy Roman Emperor, and to aid in a war against Venice. It was provided that England and the Swiss might also join the league. Henry VIII announced his adherence in August 1521. Francis I had already begun war with Charles V in Navarre, and in Italy, too, the French made the first hostile movement on 23 June 1521. Leo at once announced that he would excommunicate the king of France and release his subjects from their allegiance unless Francis I laid down his arms and surrendered Parma and Piacenza to the Church. The pope lived to hear the joyful news of the capture of Milan from the French and of the occupation by papal troops of the long-coveted provinces (November 1521).[11]

Having fallen ill with bronchopneumonia,[12] Pope Leo X died on 1 December 1521, so suddenly that the last sacraments could not be administered; but the contemporary suspicions of poison were unfounded. He was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva.[11]

Character, interests and talents

General assessment

Leo has been criticized for his handling of the events of the papacy.[13] He had a musical and pleasant voice and a cheerful temper.[14] He was eloquent in speech and elegant in his manners and epistolary style.[15] He enjoyed music and the theatre, art and poetry, the masterpieces of the ancients and the creations of his contemporaries, especially those seasoned with wit and learning. He especially delighted in ex tempore Latin verse-making (at which he excelled) and cultivated improvisatori.[16] He is said to have stated, "Let us enjoy the papacy since God has given it to us",[17] Ludwig von Pastor says that it is by no means certain that he made the remark; and historian Klemens Löffler says that "the Venetian ambassador who related this of him was not unbiased, nor was he in Rome at the time."[18] However, there is no doubt that he was by nature pleasure-loving and that the anecdote reflects his casual attitude to the high and solemn office to which he had been called.[19] On the other hand, in spite of his worldliness, Leo prayed, fasted, went to confession before celebrating Mass in public, and conscientiously participated in the religious services of the Church.[20] To the virtues of liberality, charity, and clemency he added the Machiavellian qualities of deception and shrewdness, so highly esteemed by the princes of his time.[11][21]

The character of Leo X was formerly assailed by lurid aspersions of debauchery, murder, impiety, and atheism. In the 17th century it was estimated that 300 or 400 writers, more or less, reported (on the authority of a single polemical anti-Catholic source) a story that when someone had quoted to Leo a passage from one of the Four Evangelists, he had replied that it was common knowledge "how profitable that fable of Christe hath ben to us and our companie".[22] These aspersions and more were examined by William Roscoe in the 19th century (and again by Ludwig von Pastor in the 20th) and rejected.[23] Nevertheless, even the eminent philosopher David Hume, while claiming that Leo was too intelligent to believe in Catholic doctrine, conceded that he was "one of the most illustrious princes that ever sat on the papal throne. Humane, beneficent, generous, affable; the patron of every art, and friend of every virtue".[24] Martin Luther, in a conciliatory letter to Leo, himself testified to Leo's universal reputation for morality:

Indeed, the published opinion of so many great men and the repute of your blameless life are too widely famed and too much reverenced throughout the world to be assailed by any man, of however great name, or by any arts. I am not so foolish to attack one whom everybody praises ...[25]

The final report of the Venetian ambassador Marino Giorgi supports Hume's assessment of affability and testifies to the range of Leo's talents.[26] Bearing the date of March 1517 it indicates some of his predominant characteristics:[11]

The pope is a good-natured and extremely free-hearted man, who avoids every difficult situation and above all wants peace; he would not undertake a war himself unless his own personal interests were involved; he loves learning; of canon law and literature he possesses remarkable knowledge; he is, moreover, a very excellent musician.[11]

Leo is the fifth of the six popes who are unfavourably profiled by historian Barbara Tuchman in The March of Folly, and who are accused by her of precipitating the Protestant Reformation. Tuchman describes Leo as a cultured – if religiously devout – hedonist.[27][28]

Intellectual interests

Leo X's love for all forms of art stemmed from the humanistic education he received in Florence, his studies in Pisa and his extensive travel throughout Europe when a youth. He loved the Latin poems of the humanists, the tragedies of the Greeks and the comedies of Cardinal Bibbiena and Ariosto, while relishing the accounts sent back by the explorers of the New World. Yet "Such a humanistic interest was itself religious. ... In the Renaissance, the vines of the classical world and the Christian world, of Rome, were seen as intertwined. It was a historically minded culture where artists' representations of Cupid and the Madonna, of Hercules and St. Peter could exist side-by-side".[29]

Love of music

Pastor says that "From his youth, Leo, who had a fine ear and a melodious voice, loved music to the pitch of fanaticism".[30] As pope he procured the services of professional singers, instrumentalists and composers from as far away as France, Germany and Spain. Next to goldsmiths, the highest salaries recorded in the papal accounts are those paid to musicians, who also received largesse from Leo's private purse. Their services were retained not so much for the delectation of Leo and his guests at private social functions as for the enhancement of religious services on which the pope placed great store. The standard of singing of the papal choir was a particular object of Leo's concern, with French, Dutch, Spanish and Italian singers being retained. Large sums of money were also spent on the acquisition of highly ornamented musical instruments, and he was especially assiduous in securing musical scores from Florence.[31] He also fostered technical improvements developed for the diffusion of such scores. Ottaviano Petrucci, who had overcome practical difficulties in the way of using movable type to print musical notation, obtained from Leo X the exclusive privilege of printing organ scores (which, according to the papal brief, "adds greatly to the dignity of divine worship") for a period for 15 years from 22 October 1513.[32] In addition to fostering the performance of sung Masses, he promoted the singing of the Gospel in Greek in his private chapel.[33]

Unworthy pursuits

Even those who defend him against the more outlandish attacks on his character acknowledge that he partook of entertainment such as masquerades, "jests," fowling, and hunting boar and other wild beasts.[34] According to one biographer, he was "engrossed in idle and selfish amusements".[35]

Leo indulged buffoons at his Court, but also tolerated behaviour which made them the object of ridicule. One case concerned the conceited improvisatore Giacomo Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, who was the butt of a burlesque procession organised in the style of an ancient Roman triumph. Baraballo was dressed in festal robes of velvet and with ermine and presented to the pope. He was then taken to the piazza of St Peter's and was mounted on the back of Hanno, a white elephant, the gift of King Manuel I of Portugal. The magnificently ornamented animal was then led off in the direction of the Capitol to the sound of drums and trumpets. But while crossing the bridge of Sant'Angelo over the Tiber, the elephant, already distressed by the noise and confusion around him, shied violently, throwing his passenger onto the muddy riverbank below.[36]

Sexuality

Leo's most recent biographer, Carlo Falconi, says Leo hid a private life of moral irregularity behind a mask of urbanity.[37] Scabrous verse libels of the type known as pasquinades were particularly abundant during the conclave which followed Leo's death in 1521 and made imputations about Leo's unchastity, implying or asserting homosexuality.[38] Suggestions of homosexual attraction appear in works by two contemporary historians, Francesco Guicciardini and Paolo Giovio. Zimmerman notes Giovio's "disapproval of the pope's familiar banter with his chamberlains – handsome young men from noble families – and the advantage he was said to take of them."[39]

Luther spent a month in Rome in 1510, three years before Leo became pontiff, and was disillusioned at the corruption he found there.[40] In 1520, the year before his excommunication from the Catholic Church, Luther claimed that Leo lived a "blameless life."[41] However, Luther later distanced himself from this claim and alleged in 1531 that Leo had vetoed a measure that cardinals should restrict the number of boys they kept for their pleasure, "otherwise it would have been spread throughout the world how openly and shamelessly the pope and the cardinals in Rome practice sodomy."[41] Against this allegation is the papal bull Supernae dispositionis arbitrio from 1514 which, inter alia, required cardinals to live "... soberly, chastely, and piously, abstaining not only from evil but also from every appearance of evil" and a contemporary and eye-witness at Leo's Court (Matteo Herculaneo), emphasized his belief that Leo was chaste all his life.[42]

Historians have dealt with the issue of Leo's sexuality at least since the late 18th century, and few have given credence to the imputations made against him in his later years and decades following his death, or else have at least regarded them as unworthy of notice; without necessarily reaching conclusions on whether he was homosexual.[43] Those who stand outside this consensus generally fall short of concluding with certainty that Leo was unchaste during his pontificate.[44] Joseph McCabe accused Pastor of untruthfulness and Vaughan of lying in the course of their treatment of the evidence, pointing out that Giovio and Guicciardini seemed to share the belief that Leo engaged in "unnatural vice" (homosexuality) while pope.[45]

Benevolence

Leo X made charitable donations of more than 6,000 ducats annually to retirement homes, hospitals, convents, discharged soldiers, pilgrims, poor students, exiles, cripples, and the sick and unfortunate.[46]

Death and legacy

Death

Pope Leo X died fairly suddenly of pneumonia at the age of 45 on 1 December 1521 and was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.[47] His death came just 10 months after he had excommunicated Martin Luther, the seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation, who was accused of 41 errors in his teachings.[47]

Failure to stem the Reformation

Possibly the most lasting legacy of the reign of Pope Leo X was his perceived failure not just to stem the Reformation but to fuel it.[47] A key issue was that his pontificate failed to bring about the reforms decreed by the Fifth Lateran Council (held between 1512 and 1517) which aimed to deal with many of their political problems as well as to reform Christendom, specifically relating to the papacy, cardinals, and curia. Some believe enforcing these decrees may have been enough to dampen support for radical challenges to church authority. But instead under his leadership, Rome's fiscal and political problems were deepened. A major contributor was his lavish spending (especially on the arts and himself) which led the papal treasury into mounting debt and his decision to authorize the sale of indulgences. The exploitation of people and corruption of religious principles linked to the practice of selling indulgences quickly became the key stimulus for the onset of the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther's 95 Theses, otherwise entitled "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences", was posted on a Church door in Wittenberg, Germany in October 1517 just seven months after the Lateran V was completed. But Pope Leo X's attempt to prosecute Luther's teaching on indulgences, and to eventually excommunicate him in January 1521, did not get rid of Lutheran doctrine but had the opposite effect of further splintering the Western church.[47]

Excessive spending

Leo was renowned for spending money lavishly on the arts; on charities; on benefices for his friends, relatives, and even people he barely knew; on dynastic wars, such as the War of Urbino; and on his own personal luxury. Within two years of becoming Pope, Leo X spent all of the treasure amassed by the previous Pope, the frugal Julius II, and drove the Papacy into deep debt. By the end of his pontificate in 1521, the papal treasury was 400,000 ducats in debt.[47] This debt contributed not only to the calamities of Leo's own pontificate (particularly the sale of indulgences that precipitated Protestantism) but severely constrained later pontificates (Pope Adrian VI; and Leo's beloved cousin, Clement VII) and forced austerity measures.[48]

Leo X's personal spending was likewise vast. For 1517, his personal income is recorded as 580,000 ducats, of which 420,000 came from the states of the Church, 100,000 from annates, and 60,000 from the composition tax instituted by Sixtus IV. These sums, together with the considerable amounts accruing from indulgences, jubilees, and special fees, vanished as quickly as they were received. To remain financially solvent, the Pope resorted to desperate measures: instructing his cousin, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici, to pawn the Papal jewels; palace furniture; tableware; and even statues of the apostles. Additionally, Leo sold cardinals' hats; memberships to a fraternal order he invented in 1520, the Papal Knights of St. Peter and St. Paul; and borrowed such immense sums from bankers that upon his death, many were ruined.[49]

At Leo's death, the Venetian ambassador Gradenigo estimated the number of the Church's paying offices at 2,150, with a capital value of approximately 3,000,000 ducats and a yearly income of 328,000 ducats.[50]

Patron of learning

Leo X raised the Church to a high rank as the friend of whatever seemed to extend knowledge or to refine and embellish life. He made the capital of Christendom, Rome, a centre of European culture. While yet a cardinal, he had restored the church of Santa Maria in Domnica after Raphael's designs; and as pope he had San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, on the Via Giulia, built, after designs by Jacopo Sansovino[51] and pressed forward the work on St Peter's Basilica and the Vatican under Raphael and Agostino Chigi. Leo's constitution of 5 November 1513 reformed the Roman university, which had been neglected by Julius II. He restored all its faculties, gave larger salaries to the professors, and summoned distinguished teachers from afar;[52] and, although it never attained to the importance of Padua or Bologna, it nevertheless possessed in 1514 a faculty (with a good reputation) of eighty-eight professors.

Leo called Janus Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing press from which the first Greek book printed in Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity, the ancient monuments of which formed the subject of a famous letter from Raphael to the pope in 1519.[53] The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto were papal secretaries,[54] as well as the famous poet Bernardo Accolti. Other poets, such as Marco Girolamo Vida,[55] Gian Giorgio Trissino[56] and Bibbiena, writers of novelle like Matteo Bandello, and a hundred other literati of the time were bishops, or papal scriptors or abbreviators, or in other papal employs.

Under his pontificate, Latin Christianity assumed a pagan, Greco-Roman character, which, passing from art into manners, gives to this epoch a strange complexion. Crimes for the moment disappeared, to give place to vices; but to charming vices, vices in good taste, such as those indulged in by Alcibiades and sung by Catullus. —Alexandre Dumas père[57]

Statesman

Several minor events of Leo's pontificate are worthy of mention. He was particularly friendly with King Manuel I of Portugal as a result of the latter's missionary enterprises in Asia and Africa. Pope Leo X was granted a large embassy from the Portuguese king furnished with goods from Manuel's colonies.[58] His concordat with Florence (1516) guaranteed the free election of the clergy in that city.

His constitution of 1 March 1519 condemned the King of Spain's claim to refuse the publication of papal bulls. He maintained close relations with Poland because of the Turkish advance and the Polish contest with the Teutonic Knights. His bull of July 1519, which regulated the discipline of the Polish Church, was later transformed into a concordat by Clement VII.[59]

Leo showed special favours to the Jews and permitted them to erect a Hebrew printing-press at Rome. Under Daniel Bomberg, that press produced manuscripts of the Talmud[60] and Mikraot Gedolot with Leo's approval and protection.[61]

He approved the formation of the Oratory of Divine Love, a group of pious men in Rome which later became the Theatine Order, and he canonized Francis of Paola.[62]

See also

Notes

- Alberigo, Giuseppe (1960). "Leone X, papa". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 2. Istituto Treccani.

- Löffler 1910.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project".

- Williams 1998, p. 71.

- "Pope Leo X". 7 February 2014.

- Setton 1984, p. 118.

- Phillips-Court 2011, p. 90.

- "The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church – Biographical Dictionary – Consistory of March 9, 1489". Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Minnich & Raphael 2003, pp. 1005–1052.

- Tomas 2017, p. 13.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Leo (popes) § Leo X". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Leo X, Pope (1475–1521)" (in Italian). Mediateca di Palazzo Medici Riccardi. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- Paul Strathern, The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, 2008, p. 244

- Pastor 1908, pp. 72, 74.

- Pastor 1908, p. 78.

- Roscoe gives an instance of Leo's skill (Roscoe 1806, p. 493). See also Pastor 1908, pp. 77, 149ff.

- Lilly, William Samuel. The Claims of Christianity (1894) p. 191

- Löffler, Klemens. "Pope Leo X." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 23 December 2018

- Pastor 1908, p. 76.

- Pastor 1908, p. 76 and Vaughan 1908, p. 282, both citing the Venetian ambassador Marco Minio, and also Pastor 1908, pp. 78–80.

- Virtues of benevolence: Pastor 1908, p. 81; political treachery: Roscoe 1806, pp. 464ff.

- The claim was made by John Bale in Pageant of Popes (published posthumously in 1574); for the proliferation of the story, see Pierre Bayle quoted by Roscoe 1806, pp. 479ff.

- Roscoe 1806, pp. 478–486; Pastor 1908, pp. 79–81. Vaughan, reviewing the allegation of blasphemous infidelity, called it "a spiteful and monstrous invention by a rabid or unscrupulous Reformer". (Vaughan 1908, pp. 280–283 at p. 281)

- Siebert 1990, p. 95 citing Hume's History of England (1754–1762), vol. 3, p. 95.

- Letter of 6 September 1520, published as a preface to his Freedom of a Christian. See Hans Joachim Hillerbrand, The Division of Christendom, Westminster John Knox Press (Louisville, 2007), p. 53.

- Pastor 1908, pp. 75ff.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1984). The March of Folly. Knopf. pp. 104. ISBN 978-0394527772.

- "Book review – 'The March of Folly' By Barbara W. Tuchman". faculty.webster.edu. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- Crocker III 2001, p. 222.

- Pastor 1908, p. 144.

- See generally on his love of music: Roscoe 1806, pp. 487–490 and Pastor 1908, pp. 144–148.

- Cummings 1884–1885, pp. 103ff.

- Cummings 2009, p. 586.

- Buffoonery: Roscoe 1806, pp. 491–496; Pastor 1908, pp. 77, 151–156. Fowling and hunting: Roscoe 1806, pp. 496–498; Pastor 1908, pp. 157–161; Vaughan 1908, pp. 192–214.

- Vaughan 1908, p. 283.

- Bedini 1981, pp. 79ff. And see Pastor 1908, pp. 154ff.

- Falconi, Carlo, Leone X, Milano (1987).

- See, e.g., Cesareo 1938, pp. 4ff, 78; see also references to lampoons in (Roscoe 1806, p. 464 footnote) (he also prints several in his appendix); and Pastor 1908, p. 68.

- Paolo Giovio, De Vita Leonis Decimi Pont. Max., Firenze (1548, 4 vols), written for the Medici Pope Clement VII and completed in 1533; and (covering the years 1492 to 1534) Francesco Guicciardini, Storia d'Italia, Firenze (1561, first 16 books; 1564 full edn. 20 books) written between 1537 and 1540, and published after his death in the latter year. For the characterisation of the relevant passages (few and brief) in these authors, see, e.g., Vaughan 1908, p. 280: and Wyatt, Michael, "Bibbiena's Closet: Interpretation and the Sexual Culture of a Renaissance Papal Court", comprising chap. 2 of Cestaro, Gary P. (ed.), Queer Italia, London (2004) pp. 35–54 a. To these can be added Zimmerman, T.P., Paolo Giovio: The Historian and the Crisis of Sixteenth-Century Italy, Princeton University Press (1996), citing at p. 23 Giovio's disapproval of the banter. Two pages later Zimmerman notes Giovio's penchant for gossip.

- "BBC History – Historic Figures: Martin Luther (1483–1546)". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Wilson 2007, p. 282; This allegation (made in the pamphlet Warnunge D. Martini Luther/ An seine lieben Deudschen, Wittenberg, 1531) is in stark contrast to Luther's earlier praise of Leo's "blameless life" in a conciliatory letter of his to the pope dated 6 September 1520 and published as a preface to his Freedom of a Christian. See on this, Hillerbrand 2007, p. 53.

- Passage from Supernae dispositionis arbitrio quoted by Jill Burke (Burke 2006, p. 491). Herculaneo, Matteo, publ. in Fabroni, Leonis X: Pontificis Maximi Vita at note 84, and quoted in the material part by Roscoe 1806, p. 485 in a footnote.

- Those who have rejected the evidence include: Fabroni, Angelo, Leone X: Pontificis Maximi Vita, Pisa (1797) at p. 165 with note 84; Roscoe 1806, pp. 478–486; and (Pastor 1908, pp. 80f. with a long footnote). Those who have treated of the life of Leo at any length and ignored the imputations, or summarily dismissed them, include: Gregorovius, Ferdinand, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages Eng. trans. Hamilton, Annie, London (1902, vol. VIII.1), p. 243; Vaughan 1908, p. 280; Hayes, Carlton Huntley, article "Leo X" in The Encyclopædia Britannica, Cambridge (1911, vol. XVI); Creighton, Mandell, A History of the Papacy from the Great Schism to the Sack of Rome, London (new edn., 1919), vol. 6, p. 210; Pellegrini, Marco, articles "Leone X" in Enciclopedia dei Papi, (2000, vol.3) and Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (2005, vol. 64); and Strathern, Paul The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance (a popular history), London (2003, pbk 2005), p. 277. Of these, Ludwig von Pastor and Hayes are known Catholics, and Roscoe, Gregorovius, and Creighton are known non-Catholics.

- The most recent biography of the pope speculates that his private life may have been marked by moral irregularity: Falconi, Carlo, Leone X, Milano (1987). Giovanni Dall'Orto gathered and reviewed the most relevant material (including Falconi, pp. 455–461) in an entry in Wotherspoon & Aldrich, Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History, Routledge, London and New York (2001), at p. 264, arriving only at tentative and provisional conclusions as to Leo's suggested homosexuality.

- A History of the Popes, London (1939), p. 409.

- See, e.g., Pastor 1908, p. 81

- "Pope Leo X". Reformation 500. Concordia Seminary. 7 February 2014.

- "Pope Hadrian VI". www.sgira.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- "History". Knights of St. Peter and St. Paul.

- "Luminarium Encyclopedia: Pope Leo X (1475-1521)". www.luminarium.org. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- Heydenreich, L.; Lotz, W. (1974). "Architecture in Italy 1400–1600". Pelican History of Art. pp. 195–196.

- "La storia | Sapienza Università di Roma". www.uniroma1.it. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- Hart, Vaughan, Hicks, Peter, Palladio’s Rome. Translation of Andrea Palladio’s L’Antichita di Roma and Descritione de le chiese…in la città de Roma, (1554) including as an appendix Raphael’s famous Letter to Leo X concerning Rome's ancient monuments, Yale University Press, London and New Haven, 2006.

- Paolo Giovio (1551). Vita Leonis Decimi, pontifici maximi: libri IV (in Latin). Florentiae: officina Laurentii Torrentini. p. 67.

- Lancetti, Vencenzo (1831). Della vita e degli scritti di Marco Girolamo Vida (in Italian). Milano: Giuseppe Crespi. pp. 30–31

- Ford, Jeremiah. "Giangiorgio Trissino." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 2 January 2020

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Celebrated Crimes, Vol. I. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1910, pp. 361–414

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 305.

- "Luminarium Encyclopedia: Pope Leo X (1475-1521)". www.luminarium.org. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- Heller, Marvin J (2005). "Earliest Printings of the Talmud: From Bomberg to Schottenstein" (PDF). Yeshiva University Museum: 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2016.

- Habermann, Abraham Meir (1971). Encyclopedia Judaica. Keter. p. 1195.

- Flesch, Marie. "“That spelling tho”: A Sociolinguistic Study of the Nonstandard Form of Though in a Corpus of Reddit Comments." of the 6th Conference on Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and Social Media Corpora (CMC-corpora 2018).

Sources

- Bedini, Silvio A. (30 April 1981). "The Papal Pachyderms". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 125 (2): 75–90.

- Burke, Jill (September 2006). "Sex and Spirituality in 1500s Rome [etc.]". The Art Bulletin. 88 (3): 482–495. doi:10.1080/00043079.2006.10786301. S2CID 193091974.

- Cesareo, G.A. (1938). Pasquino e pasquinate nella Roma di Leone X. Rome. pp. 74ff, 78.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cummings, Anthony (Winter 2009). "Informal Academies and Music in Pope Leo X's Rome". Italica. 86 (4): 583–601.

- Cummings, William H. (1884–1885). "Music Printing". Proceedings of the Musical Association. 11th Sess.: 99–116. doi:10.1093/jrma/11.1.99.

- Crocker III, H.W. (2001). Triumph: The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church. New York: Three Rivers Press.

- Hillerbrand, Hans Joachim (2007). The Division of Christendom. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 53.

- Löffler, Klemens (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Minnich, Nelson H.; Raphael (Winter 2003). "Raphael's Portrait "Leo X with Cardinals Giulio de' Medici and Luigi de' Rossi": A Religious Interpretation". Renaissance Quarterly. 56 (4 (n.d.)): 1005–1052. doi:10.2307/1261978. JSTOR 1261978. S2CID 191368535.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2015). Martin Luther. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. p. 281.

- Pastor, Ludwig von (1908). History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages; Drawn from the Secret Archives of the Vatican and other original sources. Vol. 8. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (English translation) - Phillips-Court, Kristin, ed. (2011). The Perfect Genre: Drama and Painting in Renaissance Italy. Ashgate Publishing.

- Roscoe, William (1806). The Life and Pontificate of Leo the Tenth. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). London.

- Siebert, Donald T. (1990). The Moral Animus of David Hume. London and New Jersey: Associated University Presses. p. 77.

- Setton, Kenneth (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571 By Kenneth Meyer Setton. Vol. 3. The American Philosophical Society.

- Tomas, Natalie R. (2017). The Medici Women: Gender and Power in Renaissance Florence. Routledge.13

- Vaughan, Herbert M. (1908). The Medici Popes. London and New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Williams, George L. (1998). Papal Genealogy: The Families and Descendants of the Popes. McFarland Inc.71

- Wilson, Derek (2007). The life and legacy of Martin Luther. Random House. p. 282.

Further reading

- Luther Martin. Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters, 2 vols., tr. and ed. by Preserved Smith, Charles Michael Jacobs, The Lutheran Publication Society, Philadelphia, Pa. 1913, 1918. vol.I (1507–1521) and vol.2 (1521–1530) from Google Books. Reprint of Vol.1, Wipf & Stock Publishers (March 2006). ISBN 1-59752-601-0

- Zophy, Jonathan W. A Short History of Renaissance and Reformation: Europe Dances over Fire and Water. 1996. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003.

External links

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Vita de Leonis X life in Latin by Paulus Jovius

- Henry VIII to Pope Leo X. 21 May 1521

- Leo X to Frederic, Elector of Saxony. Rome, 8 July 1520

- Paradoxplace Medici Popes' Page