Baroque

The Baroque (UK: /bəˈrɒk/, US: /-ˈroʊk/; French: [baʁɔk]) or Baroquism[1] is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s.[2] It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo (in the past often referred to as "late Baroque") and Neoclassical styles. It was encouraged by the Catholic Church as a means to counter the simplicity and austerity of Protestant architecture, art, and music, though Lutheran Baroque art developed in parts of Europe as well.[3]

Top: Venus and Adonis by Peter Paul Rubens (1635–1640); centre: The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Bernini (1651); bottom: the Palace of Versailles in France (c. 1660–1715) | |

| Years active | 17th–18th centuries |

|---|---|

The Baroque style used contrast, movement, exuberant detail, deep color, grandeur, and surprise to achieve a sense of awe. The style began at the start of the 17th century in Rome, then spread rapidly to the rest of Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, then to Austria, southern Germany, and Poland. By the 1730s, it had evolved into an even more flamboyant style, called rocaille or Rococo, which appeared in France and Central Europe until the mid to late 18th century. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires including the Iberian Peninsula it continued, together with new styles, until the first decade of the 19th century.

In the decorative arts, the style employs plentiful and intricate ornamentation. The departure from Renaissance classicism has its own ways in each country. But a general feature is that everywhere the starting point is the ornamental elements introduced by the Renaissance. The classical repertoire is crowded, dense, overlapping, loaded, in order to provoke shock effects. New motifs introduced by Baroque are: the cartouche, trophies and weapons, baskets of fruit or flowers, and others, made in marquetry, stucco, or carved.[4]

Origin of the word

The English word baroque comes directly from the French. Some scholars state that the French word originated from the Portuguese term barroco ("a flawed pearl"), pointing to the Latin verruca,[5] ("wart"), or to a word with the suffix -ǒccu (common in pre-Roman Iberia).[6][7][8] Other sources suggest a Medieval Latin term used in logic, baroco, as the most likely source.[9]

In the 16th century, the Medieval Latin word baroco moved beyond scholastic logic and came into use to characterise anything that seemed absurdly complex. The French philosopher Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) associated the term baroco with "Bizarre and uselessly complicated."[10] Other early sources associate baroco with magic, complexity, confusion, and excess.[9]

The word baroque was also associated with irregular pearls before the 18th century. The French baroque and Portuguese barroco were terms often associated with jewelry. An example from 1531 uses the term to describe pearls in an inventory of Charles V of France's treasures.[11] Later, the word appears in a 1694 edition of Le Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française, which describes baroque as "only used for pearls that are imperfectly round."[12] A 1728 Portuguese dictionary similarly describes barroco as relating to a "coarse and uneven pearl".[13]

An alternative derivation of the word baroque points to the name of the Italian painter Federico Barocci (1528–1612).[14]

In the 18th century, the term began to be used to describe music, and not in a flattering way. In an anonymous satirical review of the première of Jean-Philippe Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie in October 1733, which was printed in the Mercure de France in May 1734, the critic wrote that the novelty in this opera was "du barocque", complaining that the music lacked coherent melody, was unsparing with dissonances, constantly changed key and meter, and speedily ran through every compositional device.[15]

In 1762, Le Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française recorded that the term could figuratively describe something "irregular, bizarre or unequal".[16]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was a musician and composer as well as a philosopher, wrote in the Encyclopédie in 1768: "Baroque music is that in which the harmony is confused, and loaded with modulations and dissonances. The singing is harsh and unnatural, the intonation difficult, and the movement limited. It appears that term comes from the word 'baroco' used by logicians."[10][17]

In 1788, Quatremère de Quincy defined the term in the Encyclopédie Méthodique as "an architectural style that is highly adorned and tormented".[18]

The French terms style baroque and musique baroque appeared in Le Dictionnaire de l'Académie Française in 1835.[19] By the mid-19th century, art critics and historians had adopted the term "baroque" as a way to ridicule post-Renaissance art. This was the sense of the word as used in 1855 by the leading art historian Jacob Burckhardt, who wrote that baroque artists "despised and abused detail" because they lacked "respect for tradition".[20]

In 1888, the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin published the first serious academic work on the style, Renaissance und Barock, which described the differences between the painting, sculpture, and architecture of the Renaissance and the Baroque.[21]

Architecture: origins and characteristics

The Baroque style of architecture was a result of doctrines adopted by the Catholic Church at the Council of Trent in 1545–1563, in response to the Protestant Reformation. The first phase of the Counter-Reformation had imposed a severe, academic style on religious architecture, which had appealed to intellectuals but not the mass of churchgoers. The Council of Trent decided instead to appeal to a more popular audience, and declared that the arts should communicate religious themes with direct and emotional involvement.[23][24] Similarly, Lutheran Baroque art developed as a confessional marker of identity, in response to the Great Iconoclasm of Calvinists.[25]

Baroque churches were designed with a large central space, where the worshippers could be close to the altar, with a dome or cupola high overhead, allowing light to illuminate the church below. The dome was one of the central symbolic features of Baroque architecture illustrating the union between the heavens and the earth. The inside of the cupola was lavishly decorated with paintings of angels and saints, and with stucco statuettes of angels, giving the impression to those below of looking up at heaven.[26] Another feature of Baroque churches are the quadratura; trompe-l'œil paintings on the ceiling in stucco frames, either real or painted, crowded with paintings of saints and angels and connected by architectural details with the balustrades and consoles. Quadratura paintings of Atlantes below the cornices appear to be supporting the ceiling of the church. Unlike the painted ceilings of Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, which combined different scenes, each with its own perspective, to be looked at one at a time, the Baroque ceiling paintings were carefully created so the viewer on the floor of the church would see the entire ceiling in correct perspective, as if the figures were real.

The interiors of Baroque churches became more and more ornate in the High Baroque, and focused around the altar, usually placed under the dome. The most celebrated baroque decorative works of the High Baroque are the Chair of Saint Peter (1647–1653) and the Baldachino of St. Peter (1623–1634), both by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The Baldequin of St. Peter is an example of the balance of opposites in Baroque art; the gigantic proportions of the piece, with the apparent lightness of the canopy; and the contrast between the solid twisted columns, bronze, gold and marble of the piece with the flowing draperies of the angels on the canopy.[27] The Dresden Frauenkirche serves as a prominent example of Lutheran Baroque art, which was completed in 1743 after being commissioned by the Lutheran city council of Dresden and was "compared by eighteenth-century observers to St Peter's in Rome".[3]

The twisted column in the interior of churches is one of the signature features of the Baroque. It gives both a sense of motion and also a dramatic new way of reflecting light.

The cartouche was another characteristic feature of Baroque decoration. These were large plaques carved of marble or stone, usually oval and with a rounded surface, which carried images or text in gilded letters, and were placed as interior decoration or above the doorways of buildings, delivering messages to those below. They showed a wide variety of invention, and were found in all types of buildings, from cathedrals and palaces to small chapels.[28]

Baroque architects sometimes used forced perspective to create illusions. For the Palazzo Spada in Rome, Borromini used columns of diminishing size, a narrowing floor and a miniature statue in the garden beyond to create the illusion that a passageway was thirty meters long, when it was actually only seven meters long. A statue at the end of the passage appears to be life-size, though it is only sixty centimeters high. Borromini designed the illusion with the assistance of a mathematician.

Italian Baroque

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, by Donato Bramante, Michelangelo, Carlo Maderno and others, completed in 1615[29]

St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, by Donato Bramante, Michelangelo, Carlo Maderno and others, completed in 1615[29]

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, by Francesco Borromini, 1638–1677

San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, Rome, by Francesco Borromini, 1638–1677

St. Peter's Square, Rome, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1656–1667[29]

St. Peter's Square, Rome, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1656–1667[29]_-_2021-08-28_-_3.jpg.webp) Santa Maria della Pace, Rome, by Pietro da Cortona, 1656–1667[32]

Santa Maria della Pace, Rome, by Pietro da Cortona, 1656–1667[32]

The first building in Rome to have a Baroque facade was the Church of the Gesù in 1584; it was plain by later Baroque standards, but marked a break with the traditional Renaissance facades that preceded it. The interior of this church remained very austere until the high Baroque, when it was lavishly ornamented.

In Rome in 1605, Paul V became the first of series of popes who commissioned basilicas and church buildings designed to inspire emotion and awe through a proliferation of forms, and a richness of colours and dramatic effects.[33] Among the most influential monuments of the Early Baroque were the facade of St. Peter's Basilica (1606–1619), and the new nave and loggia which connected the facade to Michelangelo's dome in the earlier church. The new design created a dramatic contrast between the soaring dome and the disproportionately wide facade, and the contrast on the facade itself between the Doric columns and the great mass of the portico.[34]

In the mid to late 17th century the style reached its peak, later termed the High Baroque. Many monumental works were commissioned by Popes Urban VIII and Alexander VII. The sculptor and architect Gian Lorenzo Bernini designed a new quadruple colonnade around St. Peter's Square (1656 to 1667). The three galleries of columns in a giant ellipse balance the oversize dome and give the Church and square a unity and the feeling of a giant theatre.[35]

Another major innovator of the Italian High Baroque was Francesco Borromini, whose major work was the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane or Saint Charles of the Four Fountains (1634–1646). The sense of movement is given not by the decoration, but by the walls themselves, which undulate and by concave and convex elements, including an oval tower and balcony inserted into a concave traverse. The interior was equally revolutionary; the main space of the church was oval, beneath an oval dome.[35]

Painted ceilings, crowded with angels and saints and trompe-l'œil architectural effects, were an important feature of the Italian High Baroque. Major works included The Entry of Saint Ignatius into Paradise by Andrea Pozzo (1685–1695) in the Church of Saint Ignatius in Rome, and The triumph of the name of Jesus by Giovanni Battista Gaulli in the Church of the Gesù in Rome (1669–1683), which featured figures spilling out of the picture frame and dramatic oblique lighting and light-dark contrasts.[36]

The style spread quickly from Rome to other regions of Italy: It appeared in Venice in the church of Santa Maria della Salute (1631–1687) by Baldassare Longhena, a highly original octagonal form crowned with an enormous cupola. It appeared also in Turin, notably in the Chapel of the Holy Shroud (1668–1694) by Guarino Guarini. The style also began to be used in palaces; Guarini designed the Palazzo Carignano in Turin, while Longhena designed the Ca' Rezzonico on the Grand Canal, (1657), finished by Giorgio Massari with decorated with paintings by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo.[37] A series of massive earthquakes in Sicily required the rebuilding of most of them and several were built in the exuberant late Baroque or Rococo style.

Spanish Baroque

The Catholic Church in Spain, and particularly the Jesuits, were the driving force of Spanish Baroque architecture. The first major work in this style was the San Isidro Chapel in Madrid, begun in 1643 by Pedro de la Torre. It contrasted an extreme richness of ornament on the exterior with simplicity in the interior, divided into multiple spaces and using effects of light to create a sense of mystery.[41] The Cathedral in Santiago de Compostela was modernized with a series of Baroque additions beginning at the end of the 17th century, starting with a highly ornate bell tower (1680), then flanked by two even taller and more ornate towers, called the Obradorio, added between 1738 and 1750 by Fernando de Casas Novoa. Another landmark of the Spanish Baroque is the chapel tower of the Palace of San Telmo in Seville by Leonardo de Figueroa.[42]

Granada had only been conquered from the Moors in the 15th century, and had its own distinct variety of Baroque. The painter, sculptor and architect Alonso Cano designed the Baroque interior of Granada Cathedral between 1652 and his death in 1657. It features dramatic contrasts of the massive white columns and gold decor.

The most ornamental and lavishly decorated architecture of the Spanish Baroque is called Churrigueresque style, named after the brothers Churriguera, who worked primarily in Salamanca and Madrid. Their works include the buildings on the city's main square, the Plaza Mayor of Salamanca (1729).[42] This highly ornamental Baroque style was influential in many churches and cathedrals built by the Spanish in the Americas.

Other notable Spanish baroque architects of the late Baroque include Pedro de Ribera, a pupil of Churriguera, who designed the Royal Hospice of San Fernando in Madrid, and Narciso Tomé, who designed the celebrated El Transparente altarpiece at Toledo Cathedral (1729–1732) which gives the illusion, in certain light, of floating upwards.[42]

The architects of the Spanish Baroque had an effect far beyond Spain; their work was highly influential in the churches built in the Spanish colonies in Latin America and the Philippines. The Church built by the Jesuits for a college in Tepotzotlán, with its ornate Baroque facade and tower, is a good example.[43]

Central Europe

Poznań Fara, Poznań, Poland, by Bartłomiej Nataniel Wąsowski, Giovanni Catenazzi and Pompeo Ferrari, 1651–1732

Poznań Fara, Poznań, Poland, by Bartłomiej Nataniel Wąsowski, Giovanni Catenazzi and Pompeo Ferrari, 1651–1732

Plague Column, Vienna, Austria, by Matthias Rauchmiller and Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, 1682 and 1694[45]

Plague Column, Vienna, Austria, by Matthias Rauchmiller and Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, 1682 and 1694[45]

Interior of the Karlskirche, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, 1715–1737[47]

Interior of the Karlskirche, by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, 1715–1737[47]

From 1680 to 1750, many highly ornate cathedrals, abbeys, and pilgrimage churches were built in Central Europe, in Bavaria, Austria, Bohemia and southwestern Poland. Some were in Rococo style, a distinct, more flamboyant and asymmetric style which emerged from the Baroque, then replaced it in Central Europe in the first half of the 18th century, until it was replaced in turn by classicism.[50]

The princes of the multitude of states in that region also chose Baroque or Rococo for their palaces and residences, and often used Italian-trained architects to construct them.[51] Notable architects included Johann Fischer von Erlach, Lukas von Hildebrandt and Dominikus Zimmermann in Bavaria, Balthasar Neumann in Bruhl, and Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann in Dresden. In Prussia, Frederick II of Prussia was inspired by the Grand Trianon of the Palace of Versailles, and used it as the model for his summer residence, Sanssouci, in Potsdam, designed for him by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (1745–1747). Another work of Baroque palace architecture is the Zwinger in Dresden, the former orangerie of the palace of the Dukes of Saxony in the 18th century.

One of the best examples of a rococo church is the Basilika Vierzehnheiligen, or Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, a pilgrimage church located near the town of Bad Staffelstein near Bamberg, in Bavaria, southern Germany. The Basilica was designed by Balthasar Neumann and was constructed between 1743 and 1772, its plan a series of interlocking circles around a central oval with the altar placed in the exact centre of the church. The interior of this church illustrates the summit of Rococo decoration.[52] Another notable example of the style is the Pilgrimage Church of Wies (German: Wieskirche). It was designed by the brothers J. B. and Dominikus Zimmermann. It is located in the foothills of the Alps, in the municipality of Steingaden in the Weilheim-Schongau district, Bavaria, Germany. Construction took place between 1745 and 1754, and the interior was decorated with frescoes and with stuccowork in the tradition of the Wessobrunner School. It is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Another notable example is the St. Nicholas Church (Malá Strana) in Prague (1704–1755), built by Christoph Dientzenhofer and his son Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer. Decoration covers all of walls of interior of the church. The altar is placed in the nave beneath the central dome, and surrounded by chapels, light comes down from the dome above and from the surrounding chapels. The altar is entirely surrounded by arches, columns, curved balustrades and pilasters of coloured stone, which are richly decorated with statuary, creating a deliberate confusion between the real architecture and the decoration. The architecture is transformed into a theatre of light, colour and movement.[27]

In Poland, the Italian-inspired Polish Baroque lasted from the early 17th to the mid-18th century and emphasised richness of detail and colour. The first Baroque building in present-day Poland and probably one of the most recognizable is the Church of St. Peter and Paul in Kraków, designed by Giovanni Battista Trevano. Sigismund's Column in Warsaw, erected in 1644, was the world's first secular Baroque monument built in the form of a column.[53] The palatial residence style was exemplified by the Wilanów Palace, constructed between 1677 and 1696.[54] The most renowned Baroque architect active in Poland was Dutchman Tylman van Gameren and his notable works include Warsaw's St. Kazimierz Church and Krasiński Palace, St. Anne's in Kraków and Branicki Palace in Bialystok.[55] However, the most celebrated work of Polish Baroque is the Fara Church in Poznań, with details by Pompeo Ferrari. After Thirty Years' War under the agreements of the Peace of Westphalia two unique baroque wattle and daub structures was built: Church of Peace in Jawor, Holy Trinity Church of Peace in Świdnica the largest wooden Baroque temple in Europe.

French Baroque

Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles, 1678–1684[62]

Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles, 1678–1684[62] Garden façade of the Palace of Versailles, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1678–1688[63]

Garden façade of the Palace of Versailles, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1678–1688[63] The Marble Court of the Palace of Versailles, 1680[64]

The Marble Court of the Palace of Versailles, 1680[64]

Baroque in France developed quite differently from the ornate and dramatic local versions of Baroque from Italy, Spain and the rest of Europe. It appears severe, more detached and restrained by comparison, preempting Neoclassicism and the architecture of the Enlightenment. Unlike Italian buildings, French Baroque buildings have no broken pediments or curvilinear façades. Even religious buildings avoided the intense spatial drama one finds in the work of Borromini. The style is closely associated with the works built for Louis XIV (reign 1643–1715), and because of this, it is also known as the Louis XIV style. Louis XIV invited the master of Baroque, Bernini, to submit a design for the new wing of the Louvre, but rejected it in favor of a more classical design by Claude Perrault and Louis Le Vau.[67][68]

The main architects of the style included François Mansart (1598–1666), Pierre Le Muet (Church of Val-de-Grace, 1645–1665) and Louis Le Vau (Vaux-le-Vicomte, 1657–1661). Mansart was the first architect to introduce Baroque styling, principally the frequent use of an applied order and heavy rustication, into the French architectural vocabulary. The mansard roof was not invented by Mansart, but it has become associated with him, as he used it frequently.[69]

The major royal project of the period was the expansion of Palace of Versailles, begun in 1661 by Le Vau with decoration by the painter Charles Le Brun. The gardens were designed by André Le Nôtre specifically to complement and amplify the architecture. The Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors), the centerpiece of the château, with paintings by Le Brun, was constructed between 1678 and 1686. Mansart completed the Grand Trianon in 1687. The chapel, designed by de Cotte, was finished in 1710. Following the death of Louis XIV, Louis XV added the more intimate Petit Trianon and the highly ornate theatre. The fountains in the gardens were designed to be seen from the interior, and to add to the dramatic effect. The palace was admired and copied by other monarchs of Europe, particularly Peter the Great of Russia, who visited Versailles early in the reign of Louis XV, and built his own version at Peterhof Palace near Saint Petersburg, between 1705 and 1725.[70]

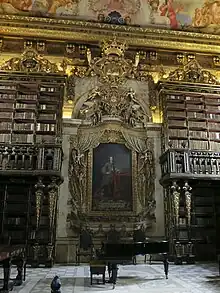

Portuguese Baroque

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Azulejo in the cloisters of the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora, Lisboa, Portugal, with a scene based on a print by Jean Le Pautre, unknown architect or craftsman, 1730–1735[73]

Azulejo in the cloisters of the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora, Lisboa, Portugal, with a scene based on a print by Jean Le Pautre, unknown architect or craftsman, 1730–1735[73].jpg.webp) Grand Staircase of the Pilgrimage Church of Bom Jesus do Monte, Braga, Portugal, by Carlos Luís Ferreira Amarante and others, c.1784[74]

Grand Staircase of the Pilgrimage Church of Bom Jesus do Monte, Braga, Portugal, by Carlos Luís Ferreira Amarante and others, c.1784[74]

Baroque architecture in Portugal lasted about two centuries (the late seventeenth century and eighteenth century). The reigns of John V and Joseph I had increased imports of gold and diamonds, in a period called Royal Absolutism, which allowed the Portuguese Baroque to flourish.

Baroque architecture in Portugal enjoys a special situation and different timeline from the rest of Europe.

It is conditioned by several political, artistic, and economic factors, that originate several phases, and different kinds of outside influences, resulting in a unique blend,[75] often misunderstood by those looking for Italian art, find instead specific forms and character which give it a uniquely Portuguese variety. Another key factor is the existence of the Jesuitical architecture, also called "plain style" (Estilo Chão or Estilo Plano)[76] which like the name evokes, is plainer and appears somewhat austere.

The buildings are single-room basilicas, deep main chapel, lateral chapels (with small doors for communication), without interior and exterior decoration, simple portal and windows. It is a practical building, allowing it to be built throughout the empire with minor adjustments, and prepared to be decorated later or when economic resources are available.

In fact, the first Portuguese Baroque does not lack in building because "plain style" is easy to be transformed, by means of decoration (painting, tiling, etc.), turning empty areas into pompous, elaborate baroque scenarios. The same could be applied to the exterior. Subsequently, it is easy to adapt the building to the taste of the time and place, and add on new features and details. Practical and economical.

With more inhabitants and better economic resources, the north, particularly the areas of Porto and Braga,[77][78][79] witnessed an architectural renewal, visible in the large list of churches, convents and palaces built by the aristocracy.

Porto is the city of Baroque in Portugal. Its historical centre is part of UNESCO World Heritage List.[80]

Many of the Baroque works in the historical area of the city and beyond, belong to Nicolau Nasoni an Italian architect living in Portugal, drawing original buildings with scenographic emplacement such as the church and tower of Clérigos,[81] the logia of the Porto Cathedral, the church of Misericórdia, the Palace of São João Novo,[82] the Palace of Freixo,[83] the Episcopal Palace (Portuguese: Paço Episcopal do Porto)[84] along with many others.

Russian Baroque

The debut of Russian Baroque, or Petrine Baroque, followed a long visit of Peter the Great to western Europe in 1697–1698, where he visited the Chateaux of Fontainebleau and Versailles as well as other architectural monuments. He decided, on his return to Russia, to construct similar monuments in St. Petersburg, which became the new capital of Russia in 1712. Early major monuments in the Petrine Baroque include the Peter and Paul Cathedral and Menshikov Palace.

During the reign of Empress Anna and Elizaveta Petrovna, Russian architecture was dominated by the luxurious Baroque style of Italian-born Bartolomeo Rastrelli, which developed into Elizabethan Baroque. Rastrelli's signature buildings include the Winter Palace, the Catherine Palace and the Smolny Cathedral. Other distinctive monuments of the Elizabethan Baroque are the bell tower of the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra and the Red Gate.[88]

In Moscow, Naryshkin Baroque became widespread, especially in the architecture of Eastern Orthodox churches in the late 17th century. It was a combination of western European Baroque with traditional Russian folk styles.

Baroque in the Spanish and Portuguese Colonial Americas

Church of San Francisco Acatepec, San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, unknown architect, 17th–18th centuries

Church of San Francisco Acatepec, San Andrés Cholula, Mexico, unknown architect, 17th–18th centuries.jpg.webp) Church of San Lorenzo de Carangas, Potosí, Bolivia, unknown architect, mid-16th century–c.1744[90][91]

Church of San Lorenzo de Carangas, Potosí, Bolivia, unknown architect, mid-16th century–c.1744[90][91]

_por_Rodrigo_Tetsuo_Argenton.jpg.webp)

Due to the colonization of the Americas by European countries, the Baroque naturally moved to the New World, finding especially favorable ground in the regions dominated by Spain and Portugal, both countries being centralized and irreducibly Catholic monarchies, by extension subject to Rome and adherents of the Baroque Counter-reformist most typical. European artists migrated to America and made school, and along with the widespread penetration of Catholic missionaries, many of whom were skilled artists, created a multiform Baroque often influenced by popular taste. The Criollo and indigenous crafters did much to give this Baroque unique features. The main centres of American Baroque cultivation, that are still standing, are (in this order) Mexico, Peru, Brazil, Ecuador, Cuba, Colombia, Bolivia, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama and Puerto Rico.

Of particular note is the so-called "Missionary Baroque", developed in the framework of the Spanish reductions in areas extending from Mexico and southwestern portions of current-day United States to as far south as Argentina and Chile, indigenous settlements organized by Spanish Catholic missionaries in order to convert them to the Christian faith and acculturate them in the Western life, forming a hybrid Baroque influenced by Native culture, where flourished Criollos and many indigenous artisans and musicians, even literate, some of great ability and talent of their own. Missionaries' accounts often repeat that Western art, especially music, had a hypnotic impact on foresters, and the images of saints were viewed as having great powers. Many natives were converted, and a new form of devotion was created, of passionate intensity, laden with mysticism, superstition, and theatricality, which delighted in festive masses, sacred concerts, and mysteries.[98][99]

The Colonial Baroque architecture in the Spanish America is characterized by a profuse decoration (portal of La Profesa Church, Mexico City; facades covered with Puebla-style azulejos, as in the Church of San Francisco Acatepec in San Andrés Cholula and Convent Church of San Francisco of Puebla), which will be exacerbated in the so-called Churrigueresque style (Facade of the Tabernacle of the Mexico City Cathedral, by Lorenzo Rodríguez; Church of San Francisco Javier, Tepotzotlán; Church of Santa Prisca of Taxco). In Peru, the constructions mostly developed in the cities of Lima, Cusco, Arequipa and Trujillo, since 1650 show original characteristics that are advanced even to the European Baroque, as in the use of cushioned walls and solomonic columns (Church of la Compañía de Jesús, Cusco; Basilica and Convent of San Francisco, Lima).[100] Other countries include: the Metropolitan Cathedral of Sucre in Bolivia; Cathedral Basilica of Esquipulas in Guatemala; Tegucigalpa Cathedral in Honduras; León Cathedral in Nicaragua; the Church of la Compañía de Jesús in Quito, Ecuador; the Church of San Ignacio in Bogotá, Colombia; the Caracas Cathedral in Venezuela; the Cabildo of Buenos Aires in Argentina; the Church of Santo Domingo in Santiago, Chile; and Havana Cathedral in Cuba. It is also worth remembering the quality of the churches of the Spanish Jesuit Missions in Bolivia, Spanish Jesuit missions in Paraguay, the Spanish missions in Mexico and the Spanish Franciscan missions in California.[101]

In Brazil, as in the metropolis, Portugal, the architecture has a certain Italian influence, usually of a Borrominesque type, as can be seen in the Co-Cathedral of Recife (1784) and Church of Nossa Senhora da Glória do Outeiro in Rio de Janeiro (1739). In the region of Minas Gerais, highlighted the work of Aleijadinho, author of a group of churches that stand out for their curved planimetry, facades with concave-convex dynamic effects and a plastic treatment of all architectural elements (Church of São Francisco de Assis in Ouro Preto, 1765–1788).

Baroque in the Spanish and Portuguese Colonial Asia

In the Portuguese colonies of India (Goa, Daman and Diu) an architectural style of Baroque forms mixed with Hindu elements flourished, such as the Goa Cathedral and the Basilica of Bom Jesus of Goa, which houses the tomb of St. Francis Xavier. The set of churches and convents of Goa was declared a World Heritage Site in 1986.

In the Philippines, which was a Spanish colony for over three centuries, a large number of Baroque constructions are preserved. Four of these as well as the Baroque and Neoclassical city of Vigan are both UNESCO World Heritage Sites; and although they lack formal classification, The Walled City of Manila along with the city of Tayabas both contain a significant extent of Baroque-era architecture.

Echoes in Wallachia and Moldavia

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Horezu Monastery, Horezu, Romania, with a Solomonic column, unknown architect, 17th-18th centuries[106]

Horezu Monastery, Horezu, Romania, with a Solomonic column, unknown architect, 17th-18th centuries[106] Door and pisanie of the Saints Constantine and Helena Church, Horezu Monastery, unknown architect or sculptor, 1692-1694

Door and pisanie of the Saints Constantine and Helena Church, Horezu Monastery, unknown architect or sculptor, 1692-1694 Maximalist railing of the Potlogi Palace, Potlogi, unknown architect, 1698

Maximalist railing of the Potlogi Palace, Potlogi, unknown architect, 1698.jpeg.webp) Twisting columns and railings of the Mogoșoaia Palace, Mogoșoaia, unknown architect, early 18th century[107]

Twisting columns and railings of the Mogoșoaia Palace, Mogoșoaia, unknown architect, early 18th century[107] Cartouche on a damaged stone in the courtyard of Antim Monastery, Bucharest, unknown sculptor, late 17th-early 18th century

Cartouche on a damaged stone in the courtyard of Antim Monastery, Bucharest, unknown sculptor, late 17th-early 18th century

As we saw, the Baroque is a Western style, born in Italy. Through the commercial and cultural relationships of Italians with countries of the Balkan Peninsula, including Moldavia and Wallachia, Baroque influences arrive to Eastern Europe. These influences were not very strong, since they usually take place in architecture and stone-sculpted ornaments, and are also mixed intensely with details taken from Byzantine and Islamic art.

Before and after the fall of the Byzantine Empire, all the art of Wallachia and Moldavia was primarily influenced by the one of Constantinople. Until the end of the 16th century, with little modifications, the plans of churches and monasteries, the murals, and the ornaments carved in stone remain the same as before. From a period starting with the reigns of Matei Basarab (1632-1654) and Vasile Lupu (1634-1653), which coincides with the popularization of Italian Baroque, new ornaments are added, and the style of religious furniture changes. This is not random at all. Decorative elements and principles are brought from Italy, through Venice, or through the Dalmatian regions, and they are adopted by architects and craftsmen from the east. The window and door frames, the pisanie with dedication, the tombstones, the columns and railings, and a part of the bronze, silver or wooden furniture, receive a more important role than the one they had before. They existed before too, inspired by the Byzantine tradition, but they have a more realist look, showing delicate floral motifs. The relief that existed before too, becomes more accentuated, having volume and consistency now. Before this period, reliefs from Wallachia and Moldavia, like the ones from the East, had only two levels, at a small distance one from the other, one at the surface and the other in depth. Big flowers, maybe roses, peonies or thistles, thick leaves, of acanthus or another similar plant, are twisting on columns, or surround door and windows. A place where the Baroque had a strong influence are columns and the railings. Capitals are more decorated than before with foliage. Columns have often twisting shafts, a local reinterpretation of the Solomonic column. Maximalist railings are placed between these columns, decorated with rinceaux. Some of the ones from the Mogoșoaia Palace are also decorated with dolphins. Cartouches are also used sometimes, mostly on tombstones, like on the one of Constantin Brâncoveanu. This movement, is known as the Brâncovenesc style, after Constantin Brâncoveanu, a ruler of Wallachia whose reign (1654-1714) is highly associated with this kind of architecture and design. The style is also present during the 18th century, and in a part of the 19th. Many of the churches and residences erected by boyards and voivodes of these periods are Brâncovenesc. Although Baroque influences can be clearly seen, the Brâncovenesc style takes much more inspiration from the local tradition.

As the 18th century passes, with the Phanariot (members of prominent Greek families in Phanar, Istanbul) reigns in Wallachia and Moldavia, Baroque influences come from Istanbul too. They came before too, during the 17th century, but with the Phanariots, more Western Baroque motifs that arrived to the Ottoman Empire have their final destination in present-day Romania. In Moldavia, Baroque elements come from Russia too, where the influence of Italian art was strong.[108]

Painting

Triumph of Bacchus and Adriane (part of The Loves of the Gods); by Annibale Carracci; c.1597–1600; fresco; length (gallery): 20.2 m; Palazzo Farnese, Rome[110]

Triumph of Bacchus and Adriane (part of The Loves of the Gods); by Annibale Carracci; c.1597–1600; fresco; length (gallery): 20.2 m; Palazzo Farnese, Rome[110].jpg.webp) The Calling of St Matthew; by Caravaggio; c.1602–1604; oil on canvas; 3 x 2 m; San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome[111]

The Calling of St Matthew; by Caravaggio; c.1602–1604; oil on canvas; 3 x 2 m; San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome[111] Judith Slaying Holofernes; by Artemisia Gentileschi; 1611–1612; oil on canvas; 163 x 126 cm; Uffizi, Florence, Italy[112]

Judith Slaying Holofernes; by Artemisia Gentileschi; 1611–1612; oil on canvas; 163 x 126 cm; Uffizi, Florence, Italy[112] The Four Continents; by Peter Paul Rubens; c.1615; oil on canvas; 209 x 284 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

The Four Continents; by Peter Paul Rubens; c.1615; oil on canvas; 209 x 284 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria.jpg.webp) The Rape of the Sabine Women; by Nicolas Poussin; 1634–1635; oil on canvas; 1.55 × 2.1 m; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City[113]

The Rape of the Sabine Women; by Nicolas Poussin; 1634–1635; oil on canvas; 1.55 × 2.1 m; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City[113] The Night Watch; by Rembrandt; 1642; oil on canvas; 3.63 × 4.37 m; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands[114]

The Night Watch; by Rembrandt; 1642; oil on canvas; 3.63 × 4.37 m; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands[114] The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba; by Claude Lorrain; 1648; oil on canvas; 149.1 × 196.7 cm; National Gallery, London

The Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba; by Claude Lorrain; 1648; oil on canvas; 149.1 × 196.7 cm; National Gallery, London Las Meninas; by Diego Velázquez; 1656; oil on canvas; 3.18 cm × 2.76 m; Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain[115]

Las Meninas; by Diego Velázquez; 1656; oil on canvas; 3.18 cm × 2.76 m; Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain[115] The Triumph of Bacchus; by Michaelina Wautier; before 1659; oil on canvas; 270 x 354 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum[116]

The Triumph of Bacchus; by Michaelina Wautier; before 1659; oil on canvas; 270 x 354 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum[116] Vanitas Still Life; by Maria van Oosterwijck; 1668; oil on canvas; 73 x 88.5 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum[117]

Vanitas Still Life; by Maria van Oosterwijck; 1668; oil on canvas; 73 x 88.5 cm; Kunsthistorisches Museum[117]

Baroque painters worked deliberately to set themselves apart from the painters of the Renaissance and the Mannerism period after it. In their palette, they used intense and warm colours, and particularly made use of the primary colours red, blue and yellow, frequently putting all three in close proximity.[118] They avoided the even lighting of Renaissance painting and used strong contrasts of light and darkness on certain parts of the picture to direct attention to the central actions or figures. In their composition, they avoided the tranquil scenes of Renaissance paintings, and chose the moments of the greatest movement and drama. Unlike the tranquil faces of Renaissance paintings, the faces in Baroque paintings clearly expressed their emotions. They often used asymmetry, with action occurring away from the centre of the picture, and created axes that were neither vertical nor horizontal, but slanting to the left or right, giving a sense of instability and movement. They enhanced this impression of movement by having the costumes of the personages blown by the wind, or moved by their own gestures. The overall impressions were movement, emotion and drama.[119] Another essential element of baroque painting was allegory; every painting told a story and had a message, often encrypted in symbols and allegorical characters, which an educated viewer was expected to know and read.[120]

Early evidence of Italian Baroque ideas in painting occurred in Bologna, where Annibale Carracci, Agostino Carracci and Ludovico Carracci sought to return the visual arts to the ordered Classicism of the Renaissance. Their art, however, also incorporated ideas central the Counter-Reformation; these included intense emotion and religious imagery that appealed more to the heart than to the intellect.[121]

Another influential painter of the Baroque era was Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. His realistic approach to the human figure, painted directly from life and dramatically spotlit against a dark background, shocked his contemporaries and opened a new chapter in the history of painting. Other major painters associated closely with the Baroque style include Artemisia Gentileschi, Elisabetta Sirani, Giovanna Garzoni, Guido Reni, Domenichino, Andrea Pozzo, and Paolo de Matteis in Italy; Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and Diego Velázquez in Spain; Adam Elsheimer in Germany; and Nicolas Poussin and Georges de La Tour in France (though Poussin spent most of his working life in Italy). Poussin and La Tour adopted a "classical" Baroque style with less focus on emotion and greater attention to the line of the figures in the painting than to colour.

Peter Paul Rubens was the most important painter of the Flemish Baroque style. Rubens' highly charged compositions reference erudite aspects of classical and Christian history. His unique and immensely popular Baroque style emphasised movement, colour, and sensuality, which followed the immediate, dramatic artistic style promoted in the Counter-Reformation. Rubens specialized in making altarpieces, portraits, landscapes, and history paintings of mythological and allegorical subjects.

One important domain of Baroque painting was Quadratura, or paintings in trompe-l'œil, which literally "fooled the eye". These were usually painted on the stucco of ceilings or upper walls and balustrades, and gave the impression to those on the ground looking up were that they were seeing the heavens populated with crowds of angels, saints and other heavenly figures, set against painted skies and imaginary architecture.[50]

In Italy, artists often collaborated with architects on interior decoration; Pietro da Cortona was one of the painters of the 17th century who employed this illusionist way of painting. Among his most important commissions were the frescoes he painted for the Palace of the Barberini family (1633–39), to glorify the reign of Pope Urban VIII. Pietro da Cortona's compositions were the largest decorative frescoes executed in Rome since the work of Michelangelo at the Sistine Chapel.[122]

François Boucher was an important figure in the more delicate French Rococo style, which appeared during the late Baroque period. He designed tapestries, carpets and theatre decoration as well as painting. His work was extremely popular with Madame Pompadour, the Mistress of King Louis XV. His paintings featured mythological romantic, and mildly erotic themes.[123]

Hispanic Americas

In the Hispanic Americas, the first influences were from Sevillan Tenebrism, mainly from Zurbarán —some of whose works are still preserved in Mexico and Peru— as can be seen in the work of the Mexicans José Juárez and Sebastián López de Arteaga, and the Bolivian Melchor Pérez de Holguín. The Cusco School of painting arose after the arrival of the Italian painter Bernardo Bitti in 1583, who introduced Mannerism in the Americas. It highlighted the work of Luis de Riaño, disciple of the Italian Angelino Medoro, author of the murals of the Church of San Pedro of Andahuaylillas. It also highlighted the Indian (Quechua) painters Diego Quispe Tito and Basilio Santa Cruz Pumacallao, as well as Marcos Zapata, author of the fifty large canvases that cover the high arches of the Cathedral of Cusco. In Ecuador, the Quito School was formed, mainly represented by the mestizo Miguel de Santiago and the criollo Nicolás Javier de Goríbar.

In the 18th century sculptural altarpieces began to be replaced by paintings, developing notably the Baroque painting in the Americas. Similarly, the demand for civil works, mainly portraits of the aristocratic classes and the ecclesiastical hierarchy, grew. The main influence was the Murillesque, and in some cases – as in the criollo Cristóbal de Villalpando – that of Valdés Leal. The painting of this era has a more sentimental tone, with sweet and softer shapes. It highlight Gregorio Vásquez de Arce in Colombia, and Juan Rodríguez Juárez and Miguel Cabrera in Mexico.

Sculpture

Saint Veronica; by Francesco Mochi; 1629–1639; Carrara marble; height: 5 m; St. Peter's Basilica, Rome

Saint Veronica; by Francesco Mochi; 1629–1639; Carrara marble; height: 5 m; St. Peter's Basilica, Rome Ecstasy of Saint Teresa; by Gian Lorenzo Bernini; 1647–1652; marble; height: 3.5 m; Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome[124]

Ecstasy of Saint Teresa; by Gian Lorenzo Bernini; 1647–1652; marble; height: 3.5 m; Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome[124] The King's Fame Riding Pegasus; by Antoine Coysevox; 1698–1702; Carrara marble; height: 3.15 m; Louvre[125]

The King's Fame Riding Pegasus; by Antoine Coysevox; 1698–1702; Carrara marble; height: 3.15 m; Louvre[125] Venus Giving Arms to Aeneas; by Jean Cornu; 1704; terracotta and painted wood; height: 108 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Venus Giving Arms to Aeneas; by Jean Cornu; 1704; terracotta and painted wood; height: 108 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.jpg.webp) The Death of Adonis; by Giuseppe Mazzuoli; 1710s; marble; height: 193 cm; Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

The Death of Adonis; by Giuseppe Mazzuoli; 1710s; marble; height: 193 cm; Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

The dominant figure in baroque sculpture was Gian Lorenzo Bernini. Under the patronage of Pope Urban VIII, he made a remarkable series of monumental statues of saints and figures whose faces and gestures vividly expressed their emotions, as well as portrait busts of exceptional realism, and highly decorative works for the Vatican such as the imposing Chair of St. Peter beneath the dome in St. Peter's Basilica. In addition, he designed fountains with monumental groups of sculpture to decorate the major squares of Rome.[126]

Baroque sculpture was inspired by ancient Roman statuary, particularly by the famous first century CE statue of Laocoön, which was unearthed in 1506 and put on display in the gallery of the Vatican. When he visited Paris in 1665, Bernini addressed the students at the academy of painting and sculpture. He advised the students to work from classical models, rather than from nature. He told the students, "When I had trouble with my first statue, I consulted the Antinous like an oracle."[127] That Antinous statue is known today as the Hermes of the Museo Pio-Clementino.

Notable late French baroque sculptors included Étienne Maurice Falconet and Jean Baptiste Pigalle. Pigalle was commissioned by Frederick the Great to make statues for Frederick's own version of Versailles at Sanssouci in Potsdam, Germany. Falconet also received an important foreign commission, creating the famous statue of Peter the Great on horseback found in St. Petersburg.

In Spain, the sculptor Francisco Salzillo worked exclusively on religious themes, using polychromed wood. Some of the finest baroque sculptural craftsmanship was found in the gilded stucco altars of churches of the Spanish colonies of the New World, made by local craftsmen; examples include the Rosary Chapel of the Church of Santo Domingo in Oaxaca (Mexico), 1724–1731.

Furniture

.jpg.webp)

_cabinet.JPG.webp) Baroque caryatids of a cabinet; c.1675; ebony, kingwood, marquetry of hard stones, gilt bronze, pewter, glass, tinted mirror and horn; unknown dimensions; Museum of Decorative Art, Strasbourg, France[129]

Baroque caryatids of a cabinet; c.1675; ebony, kingwood, marquetry of hard stones, gilt bronze, pewter, glass, tinted mirror and horn; unknown dimensions; Museum of Decorative Art, Strasbourg, France[129] Pier table; 1685–1690; carved, gessoed, and gilded wood, with a marble top; 83.6 × 128.6 × 71.6 cm; Art Institute of Chicago, US[130]

Pier table; 1685–1690; carved, gessoed, and gilded wood, with a marble top; 83.6 × 128.6 × 71.6 cm; Art Institute of Chicago, US[130] Cupboard; by André Charles Boulle; c.1700; ebony and amaranth veneering, polychrome woods, brass, tin, shell, and horn marquetry on an oak frame, gilt-bronze; 255.5 x 157.5 cm; Louvre[131]

Cupboard; by André Charles Boulle; c.1700; ebony and amaranth veneering, polychrome woods, brass, tin, shell, and horn marquetry on an oak frame, gilt-bronze; 255.5 x 157.5 cm; Louvre[131] Commode; by André Charles Boulle; c.1710–1732; walnut veneered with ebony and marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell, gilt-bronze mounts, antique marble top; 87.6 x 128.3 x 62.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)[132]

Commode; by André Charles Boulle; c.1710–1732; walnut veneered with ebony and marquetry of engraved brass and tortoiseshell, gilt-bronze mounts, antique marble top; 87.6 x 128.3 x 62.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)[132]%252C_scrittoio_a_ribalta%252C_magonza_1720_ca.jpg.webp) German slant-front desk; by Heinrich Ludwig Rohde or Ferdinand Plitzner; c.1715–1725; marquetry with maple, amaranth, mahogany, and walnut on spruce and oak; 90 × 84 × 44.5 cm; Art Institute of Chicago[133]

German slant-front desk; by Heinrich Ludwig Rohde or Ferdinand Plitzner; c.1715–1725; marquetry with maple, amaranth, mahogany, and walnut on spruce and oak; 90 × 84 × 44.5 cm; Art Institute of Chicago[133]

The main motifs used are: horns of plenty, festoons, baby angels, lion heads holding a metal ring in their mouths, female faces surrounded by garlands, oval cartouches, acanthus leaves, classical columns, caryatids, pediments, and other elements of Classical architecture sculpted on some parts of pieces of furniture,[134] baskets with fruits or flowers, shells, armour and trophies, heads of Apollo or Bacchus, and C-shaped volutes.[135]

During the first period of the reign of Louis XIV, furniture followed the previous style of Louis XIII, and was massive, and profusely decorated with sculpture and gilding. After 1680, thanks in large part to the furniture designer André Charles Boulle, a more original and delicate style appeared, sometimes known as Boulle work. It was based on the inlay of ebony and other rare woods, a technique first used in Florence in the 15th century, which was refined and developed by Boulle and others working for Louis XIV. Furniture was inlaid with plaques of ebony, copper, and exotic woods of different colors.[136]

New and often enduring types of furniture appeared; the commode, with two to four drawers, replaced the old coffre, or chest. The canapé, or sofa, appeared, in the form of a combination of two or three armchairs. New kinds of armchairs appeared, including the fauteuil en confessionale or "Confessional armchair", which had padded cushions ions on either side of the back of the chair. The console table also made its first appearance; it was designed to be placed against a wall. Another new type of furniture was the table à gibier, a marble-topped table for holding dishes. Early varieties of the desk appeared; the Mazarin desk had a central section set back, placed between two columns of drawers, with four feet on each column.[136]

Music

The term Baroque is also used to designate the style of music composed during a period that overlaps with that of Baroque art. The first uses of the term 'baroque' for music were criticisms. In an anonymous, satirical review of the première in October 1733 of Rameau's Hippolyte et Aricie, printed in the Mercure de France in May 1734, the critic implied that the novelty of this opera was "du barocque," complaining that the music lacked coherent melody, was filled with unremitting dissonances, constantly changed key and meter, and speedily ran through every compositional device.[137] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who was a musician and noted composer as well as philosopher, made a very similar observation in 1768 in the famous Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot: "Baroque music is that in which the harmony is confused, and loaded with modulations and dissonances. The singing is harsh and unnatural, the intonation difficult, and the movement limited. It appears that term comes from the word 'baroco' used by logicians."[17]

Common use of the term for the music of the period began only in 1919, by Curt Sachs,[138] and it was not until 1940 that it was first used in English in an article published by Manfred Bukofzer.[137]

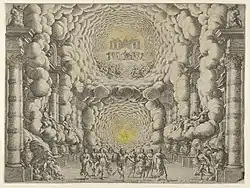

The baroque was a period of musical experimentation and innovation which explains the amount of ornaments and improvisation performed by the musicians. New forms were invented, including the concerto and sinfonia. Opera was born in Italy at the end of the 16th century (with Jacopo Peri's mostly lost Dafne, produced in Florence in 1598) and soon spread through the rest of Europe: Louis XIV created the first Royal Academy of Music, In 1669, the poet Pierre Perrin opened an academy of opera in Paris, the first opera theatre in France open to the public, and premiered Pomone, the first grand opera in French, with music by Robert Cambert, with five acts, elaborate stage machinery, and a ballet.[139] Heinrich Schütz in Germany, Jean-Baptiste Lully in France, and Henry Purcell in England all helped to establish their national traditions in the 17th century.

Several new instruments, including the piano, were introduced during this period. The invention of the piano is credited to Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) of Padua, Italy, who was employed by Ferdinando de' Medici, Grand Prince of Tuscany, as the Keeper of the Instruments.[140][141] Cristofori named the instrument un cimbalo di cipresso di piano e forte ("a keyboard of cypress with soft and loud"), abbreviated over time as pianoforte, fortepiano, and later, simply, piano.[142]

Composers and examples

- Giovanni Gabrieli (c. 1554/1557–1612) Sonata pian' e forte (1597), In Ecclesiis (from Symphoniae sacrae book 2, 1615)

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger (c. 1580–1651) Libro primo di villanelle, 20 (1610)

- Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), L'Orfeo, favola in musica (1610)

- Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672), Musikalische Exequien (1629, 1647, 1650)

- Francesco Cavalli (1602–1676), L'Egisto (1643), Ercole amante (1662), Scipione affricano (1664)

- Johann Jacob Froberger (1616–1667), Complete Music for Harpsichord and Organ, Simone Stella

- Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632–1687), Armide (1686)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704), Te Deum (1688–1698)

- Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber (1644–1704), Mystery Sonatas (1681)

- John Blow (1649–1708), Venus and Adonis (1680–1687)

- Johann Pachelbel (1653–1706), Canon in D (1680)

- Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713), 12 concerti grossi, Op. 6 (1714)

- Marin Marais (1656–1728), Sonnerie de Ste-Geneviève du Mont-de-Paris (1723)

- Henry Purcell (1659–1695), Dido and Aeneas (1688)

- Alessandro Scarlatti (1660–1725), L'honestà negli amori (1680), Il Pompeo (1683), Mitridate Eupatore (1707)

- François Couperin (1668–1733), Les barricades mystérieuses (1717)

- Tomaso Albinoni (1671–1751), Didone abbandonata (1724)

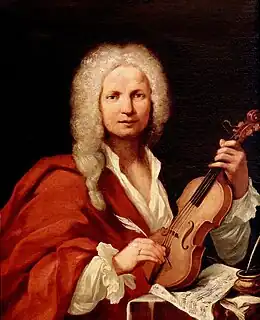

- Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741), The Four Seasons (1725)

- Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679–1745), Il Serpente di Bronzo (1730), Missa Sanctissimae Trinitatis (1736)

- Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767), Der Tag des Gerichts (1762)

- Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729)

- Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683–1764), Dardanus (1739)

- George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), Water Music (1717), Messiah (1741)

- Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757), Sonatas for harpsichord

- Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), Toccata and Fugue in D minor (1703–1707), Brandenburg Concertos (1721), St Matthew Passion (1727)

- Nicola Porpora (1686–1768), Semiramide riconosciuta (1729)

- Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710–1736), Stabat Mater (1736)

Dance

The classical ballet also originated in the Baroque era. The style of court dance was brought to France by Marie de Medici, and in the beginning the members of the court themselves were the dancers. Louis XIV himself performed in public in several ballets. In March 1662, the Académie Royale de Danse, was founded by the King. It was the first professional dance school and company, and set the standards and vocabulary for ballet throughout Europe during the period.[139]

Literary theory

Heinrich Wölfflin was the first to transfer the term Baroque to literature.[143] The key concepts of Baroque literary theory, such as "conceit" (concetto), "wit" (acutezza, ingegno), and "wonder" (meraviglia), were not fully developed in literary theory until the publication of Emanuele Tesauro's Il Cannocchiale aristotelico (The Aristotelian Telescope) in 1654. This seminal treatise - inspired by Giambattista Marino's epic Adone and the work of the Spanish Jesuit philosopher Baltasar Gracián - developed a theory of metaphor as a universal language of images and as a supreme intellectual act, at once an artifice and an epistemologically privileged mode of access to truth.[144]

Theatre

The Baroque period was a golden age for theatre in France and Spain; playwrights included Corneille, Racine and Molière in France; and Lope de Vega and Pedro Calderón de la Barca in Spain.

During the Baroque period, the art and style of the theatre evolved rapidly, alongside the development of opera and of ballet. The design of newer and larger theatres, the invention the use of more elaborate machinery, the wider use of the proscenium arch, which framed the stage and hid the machinery from the audience, encouraged more scenic effects and spectacle.[145]

The Baroque had a Catholic and conservative character in Spain, following an Italian literary model during the Renaissance.[146] The Hispanic Baroque theatre aimed for a public content with an ideal reality that manifested fundamental three sentiments: Catholic religion, monarchist and national pride and honour originating from the chivalric, knightly world.[147]

Two periods are known in the Baroque Spanish theatre, with the division occurring in 1630. The first period is represented chiefly by Lope de Vega, but also by Tirso de Molina, Gaspar Aguilar, Guillén de Castro, Antonio Mira de Amescua, Luis Vélez de Guevara, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, Diego Jiménez de Enciso, Luis Belmonte Bermúdez, Felipe Godínez, Luis Quiñones de Benavente or Juan Pérez de Montalbán. The second period is represented by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and fellow dramatists Antonio Hurtado de Mendoza, Álvaro Cubillo de Aragón, Jerónimo de Cáncer, Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla, Juan de Matos Fragoso, Antonio Coello y Ochoa, Agustín Moreto, and Francisco Bances Candamo.[148] These classifications are loose because each author had his own way and could occasionally adhere himself to the formula established by Lope. It may even be that Lope's "manner" was more liberal and structured than Calderón's.[149]

Lope de Vega introduced through his Arte nuevo de hacer comedias en este tiempo (1609) the new comedy. He established a new dramatic formula that broke the three Aristotle unities of the Italian school of poetry (action, time, and place) and a fourth unity of Aristotle which is about style, mixing of tragic and comic elements showing different types of verses and stanzas upon what is represented.[150] Although Lope has a great knowledge of the plastic arts, he did not use it during the major part of his career nor in theatre or scenography. The Lope's comedy granted a second role to the visual aspects of the theatrical representation.[151]

Tirso de Molina, Lope de Vega, and Calderón were the most important play writers in Golden Era Spain. Their works, known for their subtle intelligence and profound comprehension of a person's humanity, could be considered a bridge between Lope's primitive comedy and the more elaborate comedy of Calderón. Tirso de Molina is best known for two works, The Convicted Suspicions and The Trickster of Seville, one of the first versions of the Don Juan myth.[152]

Upon his arrival to Madrid, Cosimo Lotti brought to the Spanish court the most advanced theatrical techniques of Europe. His techniques and mechanic knowledge were applied in palace exhibitions called "Fiestas" and in lavish exhibitions of rivers or artificial fountains called "Naumaquias". He was in charge of styling the Gardens of Buen Retiro, of Zarzuela, and of Aranjuez and the construction of the theatrical building of Coliseo del Buen Retiro.[153] Lope's formulas begin with a verse that it unbefitting of the palace theatre foundation and the birth of new concepts that begun the careers of some play writers like Calderón de la Barca. Marking the principal innovations of the New Lopesian Comedy, Calderón's style marked many differences, with a great deal of constructive care and attention to his internal structure. Calderón's work is in formal perfection and a very lyric and symbolic language. Liberty, vitality and openness of Lope gave a step to Calderón's intellectual reflection and formal precision. In his comedy it reflected his ideological and doctrine intentions in above the passion and the action, the work of Autos sacramentales achieved high ranks.[154] The genre of Comedia is political, multi-artistic and in a sense hybrid. The poetic text interweaved with Medias and resources originating from architecture, music and painting freeing the deception that is in the Lopesian comedy was made up from the lack of scenery and engaging the dialogue of action.[155]

The best known German playwright was Andreas Gryphius, who used the Jesuit model of the Dutch Joost van den Vondel and Pierre Corneille. There was also Johannes Velten who combined the traditions of the English comedians and the commedia dell'arte with the classic theatre of Corneille and Molière. His touring company was perhaps the most significant and important of the 17th century.

The foremost Italian baroque tragedian was Federico Della Valle. His literary activity is summed up by the four plays that he wrote for the courtly theater: the tragicomedy Adelonda di Frigia (1595) and especially his three tragedies, Judith (1627), Esther (1627) and La reina di Scotia (1628). Della Valle had many imitators and followers who combined in their works Baroque taste and the didactic aims of the Jesuits (Pallavicino, Graziani, etc.)

Spanish colonial Americas

Following the evolution marked from Spain, at the end of the 16th century, the companies of comedians, essentially transhumant, began to professionalize. With professionalization came regulation and censorship: as in Europe, the theatre oscillated between tolerance and even government protection and rejection (with exceptions) or persecution by the Church. The theatre was useful to the authorities as an instrument to disseminate the desired behavior and models, respect for the social order and the monarchy, school of religious dogma.[156]

The corrales were administered for the benefit of hospitals that shared the benefits of the representations. The itinerant companies (or "of the league"), who carried the theatre in improvised open-air stages by the regions that did not have fixed locals, required a viceregal license to work, whose price or pinción was destined to alms and works pious.[156] For companies that worked stably in the capitals and major cities, one of their main sources of income was participation in the festivities of the Corpus Christi, which provided them with not only economic benefits, but also recognition and social prestige. The representations in the viceregal palace and the mansions of the aristocracy, where they represented both the comedies of their repertoire and special productions with great lighting effects, scenery, and stage, were also an important source of well-paid and prestigious work.[156]

Born in the Viceroyalty of New Spain[157] but later settled in Spain, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón is the most prominent figure in the Baroque theatre of New Spain. Despite his accommodation to Lope de Vega's new comedy, his "marked secularism", his discretion and restraint, and a keen capacity for "psychological penetration" as distinctive features of Alarcón against his Spanish contemporaries have been noted. Noteworthy among his works La verdad sospechosa, a comedy of characters that reflected his constant moralizing purpose.[156] The dramatic production of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz places her as the second figure of the Spanish-American Baroque theatre. It is worth mentioning among her works the auto sacramental El divino Narciso and the comedy Los empeños de una casa.

Gardens

Gardens of Versailles, by André Le Nôtre, begun in 1661[159]

Gardens of Versailles, by André Le Nôtre, begun in 1661[159] Gardens of the Het Loo Palace, Netherlands, unknown architect, 1689[160]

Gardens of the Het Loo Palace, Netherlands, unknown architect, 1689[160]

Garden of the Schwerin Castle, Schwerin, Germany, unknown architect, unknown date

Garden of the Schwerin Castle, Schwerin, Germany, unknown architect, unknown date

The Baroque garden, also known as the jardin à la française or French formal garden, first appeared in Rome in the 16th century, and then most famously in France in the 17th century in the gardens of Vaux le Vicomte and the Palace of Versailles. Baroque gardens were built by Kings and princes in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Spain, Poland, Italy and Russia until the mid-18th century, when they began to be remade into by the more natural English landscape garden.

The purpose of the baroque garden was to illustrate the power of man over nature, and the glory of its builder, Baroque gardens were laid out in geometric patterns, like the rooms of a house. They were usually best seen from the outside and looking down, either from a chateau or terrace. The elements of a baroque garden included parterres of flower beds or low hedges trimmed into ornate Baroque designs, and straight lanes and alleys of gravel which divided and crisscrossed the garden. Terraces, ramps, staircases and cascades were placed where there were differences of elevation, and provided viewing points. Circular or rectangular ponds or basins of water were the settings for fountains and statues. Bosquets or carefully trimmed groves or lines of identical trees, gave the appearance of walls of greenery and were backdrops for statues. On the edges, the gardens usually had pavilions, orangeries and other structures where visitors could take shelter from the sun or rain.[162]

Baroque gardens required enormous numbers of gardeners, continual trimming, and abundant water. In the later part of the Baroque period, the formal elements began to be replaced with more natural features, including winding paths, groves of varied trees left to grow untrimmed; rustic architecture and picturesque structures, such as Roman temples or Chinese pagodas, as well as "secret gardens" on the edges of the main garden, filled with greenery, where visitors could read or have quiet conversations. By the mid-18th century most of the Baroque gardens were partially or entirely transformed into variations of the English landscape garden.[162]

Besides Versailles and Vaux-le-Vicomte, celebrated baroque gardens still retaining much of their original appearance include the Royal Palace of Caserta near Naples; Nymphenburg Palace and Augustusburg and Falkenlust Palaces, Brühl in Germany; Het Loo Palace, Netherlands; the Belvedere Palace in Vienna; Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso, Spain; and Peterhof Palace in St. Petersburg, Russia.[162]

Posterity

Transition to rococo

.jpg.webp) Meudon Observatory, Château de Meudon, Meudon, France, an example of an early Rococo building from the last years of Louis XIV, unknown architect, 1706-1709[163]

Meudon Observatory, Château de Meudon, Meudon, France, an example of an early Rococo building from the last years of Louis XIV, unknown architect, 1706-1709[163] Chest of drawers; by Charles Cressent; c.1730; various wood types; gilt-bronze mounts and a Brèche d'Aleps marble top; height: 91.1 cm; Waddesdon Manor, Waddesdon, UK

Chest of drawers; by Charles Cressent; c.1730; various wood types; gilt-bronze mounts and a Brèche d'Aleps marble top; height: 91.1 cm; Waddesdon Manor, Waddesdon, UK

.jpg.webp) The Salon Oval de la Princesse of the Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand, Charles-Joseph Natoire and Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, 1737-1739

The Salon Oval de la Princesse of the Hôtel de Soubise, Paris, by Germain Boffrand, Charles-Joseph Natoire and Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne, 1737-1739 The Triumph of Venus; by François Boucher; 1740; oil on canvas; 130 × 162 cm; Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden

The Triumph of Venus; by François Boucher; 1740; oil on canvas; 130 × 162 cm; Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden.jpeg.webp) Vieux-Laque Room, Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austria, decorated with Chinese black lacquerware panels, by Nikolaus Pacassi, 1743-1763[165]

Vieux-Laque Room, Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna, Austria, decorated with Chinese black lacquerware panels, by Nikolaus Pacassi, 1743-1763[165] Gate with two statues and elaborate wrought-iron grilles, Würzburg, Germany, grilles by Johann Georg Oegg, 1752

Gate with two statues and elaborate wrought-iron grilles, Würzburg, Germany, grilles by Johann Georg Oegg, 1752 Chinese House, Sanssouci Park, Potsdam, Germany, an example of Chinoiserie, by Johann Gottfried Büring, 1755–1764[166]

Chinese House, Sanssouci Park, Potsdam, Germany, an example of Chinoiserie, by Johann Gottfried Büring, 1755–1764[166]%252C.jpg.webp) Coffeepot, decorated with foliage; 1757; silver; height: 29.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Coffeepot, decorated with foliage; 1757; silver; height: 29.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.jpg.webp) The Music Lesson; by the Chelsea Porcelain Factory; c.1765; soft-paste porcelain; 39.1 × 31.1 × 22.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Music Lesson; by the Chelsea Porcelain Factory; c.1765; soft-paste porcelain; 39.1 × 31.1 × 22.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Pagod, based on Asian figures of Budai, an example of Chinoiserie; by Johann Joachim Kändler; c.1765; hard paste porcelain; Metropolitan Museum of Art[167]

Pagod, based on Asian figures of Budai, an example of Chinoiserie; by Johann Joachim Kändler; c.1765; hard paste porcelain; Metropolitan Museum of Art[167]%252C_RP-P-2011-164-8.jpg.webp) Cartouche from the Second Livre de Cartouches, an example of asymmetry; c.1710-1772; engraving on paper; 23 x 19.8 cm; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Cartouche from the Second Livre de Cartouches, an example of asymmetry; c.1710-1772; engraving on paper; 23 x 19.8 cm; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

The Rococo is the final stage of the Baroque, and in many ways took the Baroque's fundamental qualities of illusion and drama to their logical extremes. Beginning in France as a reaction against the heavy Baroque grandeur of Louis XIV's court at the Palace of Versailles, the rococo movement became associated particularly with the powerful Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), the mistress of the new king Louis XV (1710–1774). Because of this, the style was also known as 'Pompadour'. Although it's highly associated with the reign of Louis XV, it didn't appear in this period. Multiple works from the last years of Louis XIV's reign are examples of early Rococo. The name of the movement derives from the French 'rocaille', or pebble, and refers to stones and shells that decorate the interiors of caves, as similar shell forms became a common feature in Rococo design. It began as a design and decorative arts style, and was characterized by elegant flowing shapes. Architecture followed and then painting and sculpture. The French painter with whom the term Rococo is most often associated is Jean-Antoine Watteau, whose pastoral scenes, or fêtes galantes, dominate the early part of the 18th century.

There are multiple similarities between Rococo and Baroque. Both styles insist on monumental forms, and so use continuous spaces, double columns or pilasters, and luxurious materials (including gilded elements). There also noticeable differences. Rococo designed freed themselves from the adherence to symmetry that had dominated architecture and design since the Renaissance. Many small objects, like ink pots or porcelain figures, but also some ornaments, are often asymmetrical. This goes hand in hand with the fact that most ornamentation consisted of interpretation of foliage and sea shells, not as many Classical ornaments inherited from the Renaissance like in Baroque. Another key difference is the fact that since the Baroque is the main cultural manifestation of the spirit of the Counter-Reformation, it is most often associated with ecclesiastical architecture. In contrast, the Rococo is mainly associated with palaces and domestic architecture. In Paris, the popularity of the Rococo coincided with the emergence of the salon as a new type of social gathering, the venues for which were often decorated in this style. Rococo rooms were typically smaller than their Baroque counterparts, reflecting a movement towards domestic intimacy.[168] Colours also match this change, from the earthy tones of Caravaggio's paintings, and the interiors of red marble and gilded mounts of the reign of Louis XIV, to the pastel and relaxed pale blue, Pompadour pink, and white of the Louis XV and Madame de Pompadour's France. Similarly to colours, there was also a transition from serious, dramatic and moralistic subjects in painting and sculpture, to lighthearted and joyful themes.

One last difference between Baroque and Rococo is the interest that 18th century aristocrats had for East Asia. Chinoiserie was a style in fine art, architecture and design, popular during the 18th century, that was heavily inspired by Chinese art, but also by Rococo at the same time. Because traveling to China or other Far Eastern countries was something hard at that time and so remained mysterious to most Westerners, European imagination were fuelled by perceptions of Asia as a place of wealth and luxury, and consequently patrons from emperors to merchants vied with each other in adorning their living quarters with Asian goods and decorating them in Asian styles. Where Asian objects were hard to obtain, European craftsmen and painters stepped up to fill the demand, creating a blend of Rococo forms and Asian figures, motifs and techniques. Aside from European recreations of objects in East Asian style, Chinese lacquerware was reused in multiple ways. European aristicrats fully decorated a handful of rooms of palaces, with Chinese lacquer panels used as wall panels. Due to its aspect, black lacquer was popular for Western men's studies. Those panels used were usually glossy and black, made in the Henan province of China. They were made of multiple layers of lacquer, then incised with motifs in-filled with colour and gold. Chinese, but also Japanese lacquer panels were also used by some 18th century European carpenters for making furniture. In order to be produced, Asian screens were dismantled and used to veneer European-made furniture.

Complete abandonment with Neoclassicism

.jpg.webp)

This caricature contrasts Rococo 1778 (at right) and Neoclassical 1793 (at left) styles for both men and women, showing the large changes in just 15 years, and overall the contrast between the Baroque and Rococo fashion with a lot of lacework and wigs, and the simplicity and the same time elegance of Neoclassical outfits

This caricature contrasts Rococo 1778 (at right) and Neoclassical 1793 (at left) styles for both men and women, showing the large changes in just 15 years, and overall the contrast between the Baroque and Rococo fashion with a lot of lacework and wigs, and the simplicity and the same time elegance of Neoclassical outfits Rue Jacob no. 46, an example of the Directoire style (a period in French Neoclassicism), very minimalist compared to Baroque or Rococo facades, Paris, unknown architect, unknown date

Rue Jacob no. 46, an example of the Directoire style (a period in French Neoclassicism), very minimalist compared to Baroque or Rococo facades, Paris, unknown architect, unknown date.jpg.webp)

Empire style dress of Madame Récamier, in very different to Baroque and Rococo fashion, painted by François Gérard, 1802

Empire style dress of Madame Récamier, in very different to Baroque and Rococo fashion, painted by François Gérard, 1802 Empire style vase, very different from the blue-and-white ceramics of the 17th century; 1809; hard-paste porcelain and gilded bronze handles; height: 74.9 cm, diameter: 35.6 cm; Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, US[173]

Empire style vase, very different from the blue-and-white ceramics of the 17th century; 1809; hard-paste porcelain and gilded bronze handles; height: 74.9 cm, diameter: 35.6 cm; Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, US[173]

In 1750, Madame de Pompadour sent her nephew, Abel-François Poisson de Vandières, on a two-year mission to study artistic and archeological developments in Italy. He was accompanied by several artists, including the engraver Nicolas Cochin and the architect Soufflot. They returned to Paris with a passion for classical art. Vandiéres became the Marquis of Marigny, and was named Royal Director of buildings in 1754. He turned official French architecture toward Neoclassicism, a movement that heavily takes its inspiration from and tries to revive the art of Ancient Greece and Rome. Cochin became an important art critic; he denounced the petit style of François Boucher (one of the main Rococo painters), and called for a grand style with a new emphasis on antiquity and nobility in the academies of painting of architecture.[174]