Mascaron (architecture)

In architecture and the decorative arts, a mascaron ornament is a face, usually human, sometimes frightening or chimeric, whose alleged function was originally to frighten away evil spirits so that they would not enter the building.[1] The concept was subsequently adapted to become a purely decorative element. The most recent architectural styles to extensively employ mascarons were Beaux Arts and Art Nouveau.[2][3] In addition to architecture, mascarons are used in the other applied arts.

Types

Green Man

In the 11th century, European stonemasons began adding carved foliate mascarons, known as Green Men, to the decoration of churches, an image that early 20th-century scholars suggested had secretly represented a surviving pre-Christian god. Today, few scholar believe this idea. The Green Man is primarily interpreted as a symbol of rebirth, representing the cycle of new growth that occurs every spring.[4]

.jpg.webp) Early Byzantine mosaic with a foliate head, possibly from the reign of Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), Great Palace Mosaic Museum, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey)[5]

Early Byzantine mosaic with a foliate head, possibly from the reign of Byzantine emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565), Great Palace Mosaic Museum, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey)[5].jpg.webp)

Second Empire style ceiling with a foliate head in the Napoleon III Apartments, in the Louvre Palace, Paris, designed by Hector Lefuel and decorated with paintings by Charles Raphaël Maréchal, 1859-1860[7]

Second Empire style ceiling with a foliate head in the Napoleon III Apartments, in the Louvre Palace, Paris, designed by Hector Lefuel and decorated with paintings by Charles Raphaël Maréchal, 1859-1860[7].jpg.webp)

Bucranium

A bucranium (plural bucrania) is basically an ox skull mascaron, usually used in Antiquity, for decorating funerary and commemorative monuments. The motif originated in a ceremony wherein an ox's head was hung from the wooden beams supporting the temple roof; this scene was later represented, in stone, on the frieze, or stone lintels, above the columns in Doric temples. The ox skull is usually decorated with ribbons and festoons. The motif is reused during the Renaissance, losing its Ancient symbolism, being reduced only to a simple ornament. Later it is no longer used until the 18th century, when the excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum lead to Neoclassicism, a movement that tried to revive the aesthetic of Classical Greece and Rome.[8][9]

Ancient Greek bucrania on a bell krater from Rudiae with an offering scene, by the Bucranium Painter, c.375-350 BC, ceramic, Museo archeologico Sigismondo Castromediano, Lecce, Italy

Ancient Greek bucrania on a bell krater from Rudiae with an offering scene, by the Bucranium Painter, c.375-350 BC, ceramic, Museo archeologico Sigismondo Castromediano, Lecce, Italy

Rococo bucrania on the foot of a potpurri vase, by Jean-Pierre Ador, 1768, multicoloured gold, en plein and basse-taille enamel, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, US[10]

Rococo bucrania on the foot of a potpurri vase, by Jean-Pierre Ador, 1768, multicoloured gold, en plein and basse-taille enamel, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, US[10].jpg.webp) Neoclassical bucrania on a gueridon (small high table) from the salon of madame Récamier, c.1790, mahogany, gilt bronze and marble, Louvre[11]

Neoclassical bucrania on a gueridon (small high table) from the salon of madame Récamier, c.1790, mahogany, gilt bronze and marble, Louvre[11] Beaux Arts mosaic of bucrania and festoons on the Grand Palais, Paris, by Charles Girault, 1897-1900

Beaux Arts mosaic of bucrania and festoons on the Grand Palais, Paris, by Charles Girault, 1897-1900

History

In Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, mascarons were used mainly for decoration, but sometimes for threatening evil spirits. Since the Baroque, they were only used as an ornament, usually presented at the tops of various things (window or door keystones, handles, cartouches etc.).

Ancient Near East and Egypt

Mascarons were rarely present in the Ancient Near East. The ones used usually take the form of bull or lion heads. Good examples can be seen at the Lyres of Ur.

In ancient Egypt, Hathor was the supreme goddess of love, identified by the Greeks with Aphrodite. Her face was used for decorating multiple objects. She was most often depicted as a woman wearing a headdress with horns and a sun disk. Mirrors and sistra (a musical instrument used in ancient Egypt) feature a Hathor mascaron on the handle. Some mirrors feature her because in Egypt they were often made of gold or bronze and therefore symbolized the sun disk, and because they were connected with beauty and femininity.[12] Hathor was sometimes represented as a human face with bovine ears. This mask-like face was placed on the capitals of columns beginning in the late Old Kingdom. Columns of this style were used in many temples to Hathor and other goddesses.[13] Mascarons were also present on Egyptian canopic jars. These were vessels used for storing the internal organs removed during mummification. The earliest jars were simple, but during the First Intermediate Period, the lids of the jars began to be modelled in the form of human heads. From the 18th Dynasty, they were designed each with a different mascaron, so they resemble the four sons of Horus (baboon, jackal, falcon and human).[14]

.jpg.webp) Sumerian bull mascaron for a lyre, c.2600–2350 BC, bronze, inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Sumerian bull mascaron for a lyre, c.2600–2350 BC, bronze, inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Sumerian bull mascaron of the Queen's lyre from Puabi's grave, c.2500 BC, lapis lazuli, shell and gold, British Museum, London

Sumerian bull mascaron of the Queen's lyre from Puabi's grave, c.2500 BC, lapis lazuli, shell and gold, British Museum, London.jpg.webp) Ancient Egyptian mirror with a Hathor mascaron, c.1479–1425, disk: silver, handle: wood sheathed in gold with restored inlay, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ancient Egyptian mirror with a Hathor mascaron, c.1479–1425, disk: silver, handle: wood sheathed in gold with restored inlay, Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Ancient Egyptian canopic jars, 744-656 BC, painted sycomore fig wood, British Museum[15]

Ancient Egyptian canopic jars, 744-656 BC, painted sycomore fig wood, British Museum[15] Ancient Egyptian sistrum with a Hathor mascaron, c.305–282 BC, faience, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ancient Egyptian sistrum with a Hathor mascaron, c.305–282 BC, faience, Metropolitan Museum of Art Ancient Egyptian mascarons of Hathoric column capitals from the Dendera Temple complex, Dendera, Egypt, unknown architect, 1st century AD

Ancient Egyptian mascarons of Hathoric column capitals from the Dendera Temple complex, Dendera, Egypt, unknown architect, 1st century AD

Greco-Roman world

In ancient Greece, Rome, and in the architecture of the Etruscan civilization, lion mascarons were often used to decorate temple cornices. The tile-ends at the edges of a roof were concealed by ornamental blocks known as antefixae, which were sometimes decorated with human mascarons.[16]

Sometimes, mascarons were used for threatening. Medusa decorates the architrave of the temple of Didyma, and is intended to frighten the enemies of Apollo, stylized so as to be seen from a distance and allow play of light and shadow.

Besides faces, mascarons sometimes took the form of theatre masks. Theatrical manifestations are initially a sacred ceremony linked to the cult of Dionysus. These sacred ceremonies are reflected in decorative friezes with the faces of Dionysos (a.k.a. Bacchus), maenads (bacchantes among the Romans), satyrs, and Silenus, all with festoons between them, decorating religious buildings.

Later, the Roman Empire took all these decorative elements, as they incorporated many cultural elements of Ancient Greece.

Ancient Greek mascaron of a gorgon from the sanctuary of Apollo, Didyma, present-day Turkey, unknown architect, 6th and 3rd centuries BC

Ancient Greek mascaron of a gorgon from the sanctuary of Apollo, Didyma, present-day Turkey, unknown architect, 6th and 3rd centuries BC.jpg.webp)

_MET_DP207966.jpg.webp)

%252C_ADUT365(8).jpg.webp) Etruscan vessel with a single handle, in the shape of a satyr's head, c.340 BC, ceramic, Petit Palais, Paris

Etruscan vessel with a single handle, in the shape of a satyr's head, c.340 BC, ceramic, Petit Palais, Paris.jpg.webp)

Polychrome Roman mask mascarons on the border of a mosaic with doves drinking from a golden basin, after Sosus of Pergamon, 1st century BC, mosaic, National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy[19]

Polychrome Roman mask mascarons on the border of a mosaic with doves drinking from a golden basin, after Sosus of Pergamon, 1st century BC, mosaic, National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy[19].jpg.webp) Roman head of Medusa, 37-41 AD, bronze, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome[20]

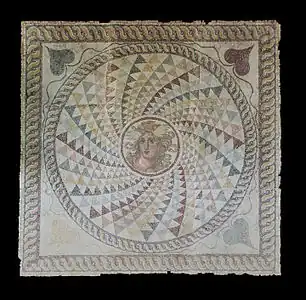

Roman head of Medusa, 37-41 AD, bronze, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome[20] Medusa mascaron on a mosaic floor, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece, unknown architect or craftsman, 2nd century[21]

Medusa mascaron on a mosaic floor, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece, unknown architect or craftsman, 2nd century[21] Roman mascarons on a sarcophagus, 2nd century, stone, Antalya Museum, Konyaaltı, Turkey

Roman mascarons on a sarcophagus, 2nd century, stone, Antalya Museum, Konyaaltı, Turkey

Ancient China

In the Neolithic period in China, small jade objects were created. The hardness of jade gives it durability, which helped at its conservation over millennia. Some of these objects, like the cong, a straight tube with a circular interior and square outer section, were decorated with highly stylized mascarons.

During the Chinese Bronze Age (the Shang and Zhou dynasties), court intercessions and communication with the spirit world were conducted by a shaman (possibly the king himself). In the Shang dynasty (c.1600–1050 BC), the supreme deity was Shangdi, but aristocratic families preferred to contact the spirits of their ancestors. They prepared elaborate banquets of food and drink for them, heated and served in bronze ritual vessels. These bronze vessels had many shapes, depending on their purpose: for wine, water, cereals or meat, and some of them were marked with readable characters, which shows the development of writing. One of the most commonly used motifs on these vessels was the taotie, a stylized mascaron divided symmetrically, with nostrils, eyes, eyebrows, jaws, cheeks and horns, surrounded by incised patterns.[22]

Highly stylized mascarons on a cong, produced by the Liangzhu culture, c.2500 BC, jade, British Museum, London

Highly stylized mascarons on a cong, produced by the Liangzhu culture, c.2500 BC, jade, British Museum, London

Taotie on a hu (ritual altar vessel), c.1100 BC, cast bronze, British Museum

Taotie on a hu (ritual altar vessel), c.1100 BC, cast bronze, British Museum_masks%252C_handle_2%252C_China%252C_Warring_States_Period%252C_475-221_BC%252C_bronze_-_Fitchburg_Art_Museum_-_DSC08852.JPG.webp) Taotie of a handle, 475-221 BC, bronze, Fitchburg Art Museum, Fitchburg, US

Taotie of a handle, 475-221 BC, bronze, Fitchburg Art Museum, Fitchburg, US Mascaron on an ornamental handle of a bi disc, c.100 BC, jade, Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Mascaron on an ornamental handle of a bi disc, c.100 BC, jade, Museum of the Mausoleum of the Nanyue King, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica

Aztec facade of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent (detail reconstruction), Teotihuacan, Mexico, c.225[23]

Aztec facade of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent (detail reconstruction), Teotihuacan, Mexico, c.225[23]

Middle Ages

The use of mascarons continued during the Middle Ages. They are found in Gothic architecture, especially in the 14th century [24] Mascarons were also used in medieval Russian architecture.

Russian mascarons of the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl, Bogolyubovo, Russia, unknown architect or sculptor, 1165[25]

Russian mascarons of the Church of the Intercession on the Nerl, Bogolyubovo, Russia, unknown architect or sculptor, 1165[25] Romanesque mascaron of the Église de la Trinité d'Angers, Angers, France, c.1150-1175, unknown architect or sculptor[26]

Romanesque mascaron of the Église de la Trinité d'Angers, Angers, France, c.1150-1175, unknown architect or sculptor[26] Romanesque mascaron of the Église de la Trinité d'Angers, Angers, France, c.1150-1175, unknown architect or sculptor[27]

Romanesque mascaron of the Église de la Trinité d'Angers, Angers, France, c.1150-1175, unknown architect or sculptor[27]._1230-1234%253B_collapsed_and_rebuilt_in_15th_c._Detail_of_a_stone_carving_in_the_exterior_wall._(6349686387).jpg.webp) Russian mascarons on the Saint George Cathedral, Yuryev-Polsky, Russia, unknown architect or sculptor, 1230-1234, collapsed and was rebuilt in 1471[28]

Russian mascarons on the Saint George Cathedral, Yuryev-Polsky, Russia, unknown architect or sculptor, 1230-1234, collapsed and was rebuilt in 1471[28]

Renaissance

Renaissance artists reread the myths of Greco-Roman Antiquity which gave them new subjects and ornaments. Archaeological discoveries like the excavations of the Baths of Caracalla by the farneses, or Laocoön and His Sons, inspired sculptors and architects of the 15th and 16th centuries. The Villa of Emperor Hadrian and the Pantheon in Rome offer construction models radically different from the Gothic style. The forms of Antiquity are coming back into fashion: columns, pilasters, pediments, domes, and statues decorate the buildings of this era.

In the Quattrocento, the last Gothic influences tended to disappear; It was not until the beginning of the 16th century that the decorative faces of Antiquity took their place again in the form of mascarons.

The Renaissance fashion spread into the rest of Western Europe. It arrived in France with the Italian Wars. Rosso Fiorentino (born in Florence in 1494, died in Fontainebleau in 1540) and Le Primatice (born in Bologna in 1504 and died in Paris in 1570) came to work at Fontainebleau for the King of France Francis I. Rosso, who worked in Italy until the sack of the city of Rome in 1527, mastered the stucco technique. Le Primaticce had collaborated in Mantua with Giulio Romano.

Mascaron adorning the front door of the campanile of the Church of Santa Maria Formosa, Venice, Italy, designed by Mauro Codussi, 1492

Mascaron adorning the front door of the campanile of the Church of Santa Maria Formosa, Venice, Italy, designed by Mauro Codussi, 1492 Mascarons on a column of the Gouverneto Monastery, Greece, unknown architect or sculptor, 1537[29] (although other sources say 1548)[30]

Mascarons on a column of the Gouverneto Monastery, Greece, unknown architect or sculptor, 1537[29] (although other sources say 1548)[30]

Baroque and Rococo

Succeeding Mannerism, and developing as a result of religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants across Europe, Baroque art emerged in the late 16th century. The name may derive from 'barocco', the Portuguese word for misshaped pearl, and it describes art that combined emotion, dynamism and drama with powerful color, realism and strong tonal contrasts. Between 1545 and 1563 at the Council of Trent, it was decided that religious art must encourage piety, realism and accuracy, and, by attracting viewers' attention and empathy, glorify the Catholic Church and strengthen the image of Catholicism. Since Baroque architecture and design extended the classical vocabulary of the Renaissance, mascarons continued to be used. During the 17th and 18th centuries, they were most often decorated keystones above arched doors or windows, inside a cartouche. They were present especially at the first floor of many palaces, which often have continuous arched windows and doors. Another frequent use was at the top of cartouches.

The Baroque was followed by the Rococo, which kept some of characteristics of the Baroque, like monumentality and curving shapes, but came with new features, like pastel colours, foliate ornamentation, asymmetry and an emphasis on secular architecture. The Rococo is also mainly associated with palace and domestic architecture, compared to how the Baroque is often seen as a mainly ecclesiastical style. One of the most noticeable characteristic is its delicacy. Besides the use of curving lines and flowers, the fanciness of the style is also visible in the many artworks that show scenes of aristocratic life. People in Rococo painting by artists like Antoine Watteau, Jean-Baptiste van Loo, François Boucher, or Jean Siméon Chardin have cupid-like faces. Of course, this feature is present in sculpture too, including mascarons. Like in the case of Baroque architecture, most Rococo mascarons are placed on keystones of arched doors or windows. Good examples of them are present at most hôtel particuliers from the reign of Louis XV (1715-1774).

The interactions between Western European nations and the rest of the world brought on by colonialist exploration have had an impact on aesthetics. Rarely, for making a building of an object more over the top, mascarons of Native Americans were added, showing them with stereotypical feather headdresses. Similarly, mascarons of Sub-Saharian Africans were added on buildings from the Place de la Bourse in Bordeaux, France. They are the result of the fact that colonization and slavery contributed to the wealth of the city of Bordeaux, both through the slave trade, the trade in goods produced by slaves and the possession of plantations. Out of all these forms of exoticism, the most popular one was Chinoiserie, a style in fine art, architecture and design, popular during the 18th century, that was heavily inspired by Chinese art, but also by Rococo at the same time. Because traveling to China or other Far Eastern countries was something hard at that time and so remained mysterious to most Westerners, European imagination were fuelled by perceptions of Asia as a place of wealth and luxury, and consequently patrons from emperors to merchants vied with each other in adorning their living quarters with Asian goods and decorating them in Asian styles. Where Asian objects were hard to obtain, European craftsmen and painters stepped up to fill the demand, creating a blend of Rococo forms and Asian figures, motifs and techniques. As a result, some European aristocrats built garden pavilion inspired by what architects imaged Chinese architecture as looking like. Of course, many of their elements are much closer to the Rococo than to Qing dynasty palaces. Some of these structures feature mascarons of people from the Far East, like in the case of the Chinese House from the Sanssouci Park in Potsdam, Germany, or the Chinese Pavilion from the gardens of the Drottningholm Palace in Sweden.[31]

Baroque mascaron of a clock with rais, visual manifestation of the metaphor Sun King (le Roi Soleil) for Louis XIV, on the Marble Court facade of the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France, designed by Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, c. 1660-1715

Baroque mascaron of a clock with rais, visual manifestation of the metaphor Sun King (le Roi Soleil) for Louis XIV, on the Marble Court facade of the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France, designed by Louis Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, c. 1660-1715 Baroque Hercules mascaron of the Dôme des Invalides, Paris, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1677–1706[32]

Baroque Hercules mascaron of the Dôme des Invalides, Paris, by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1677–1706[32] Baroque mascaron in the Hall of Mirrors, Palace of Versailles, designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1678-1684[33]

Baroque mascaron in the Hall of Mirrors, Palace of Versailles, designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart, 1678-1684[33] Baroque mascaron on the pedestal of a clock, designed and made by André Charles Boulle, c.1690, gilt wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Baroque mascaron on the pedestal of a clock, designed and made by André Charles Boulle, c.1690, gilt wood, Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC Rococo mascaron above the door of the Hôtel de Chenizot (Rue Saint-Louis-en-l'Île no. 51–53), Paris, designed by Pierre Vigné de Vigny, 1719

Rococo mascaron above the door of the Hôtel de Chenizot (Rue Saint-Louis-en-l'Île no. 51–53), Paris, designed by Pierre Vigné de Vigny, 1719 Rococo Native American mascaron on a corbel of a balcony of the Hôtel de Salm-Dyck (Rue du Bac no. 97), Paris, designed by François Debias-Aubry, 1722

Rococo Native American mascaron on a corbel of a balcony of the Hôtel de Salm-Dyck (Rue du Bac no. 97), Paris, designed by François Debias-Aubry, 1722 Baroque putti mascarons on a column of the El Transparente altarpiece, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain, designed and made by Narciso Tomé, 1729-1732[34]

Baroque putti mascarons on a column of the El Transparente altarpiece, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain, designed and made by Narciso Tomé, 1729-1732[34] Rococo cartouche with two horse mascarons and a Green Man at the bottom, on the facade of the Palais Rohan, Strasbourg, France, 1732-1742

Rococo cartouche with two horse mascarons and a Green Man at the bottom, on the facade of the Palais Rohan, Strasbourg, France, 1732-1742 Rococo mascaron in the courtyard of the Hôtel Le Lièvre de la Grange (Rue de Braque no. 4–6), Paris, designed by Victor-Thierry Dailly, 1734-1735

Rococo mascaron in the courtyard of the Hôtel Le Lièvre de la Grange (Rue de Braque no. 4–6), Paris, designed by Victor-Thierry Dailly, 1734-1735 Rococo mascaron on a building in Place Stanislas, Nancy, France, designed by Emmanuel Héré de Corny, 1752-1756

Rococo mascaron on a building in Place Stanislas, Nancy, France, designed by Emmanuel Héré de Corny, 1752-1756 Rococo candelabrum vase with elephant mascarons, 1757–1758, by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, probably designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis, soft-paste porcelain with enamel and gilding, Art Institute of Chicago, US

Rococo candelabrum vase with elephant mascarons, 1757–1758, by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, probably designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis, soft-paste porcelain with enamel and gilding, Art Institute of Chicago, US Rococo mascaron of an African woman in a cartouche on a building in the Place de la Bourse, Bordeaux, France, unknown architect and sculptor, 18th century

Rococo mascaron of an African woman in a cartouche on a building in the Place de la Bourse, Bordeaux, France, unknown architect and sculptor, 18th century Chinoiserie mascaron above a window of the Chinese Pavilion, Ekerö Municipality, Sweden, designed by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, 1763–1769[35]

Chinoiserie mascaron above a window of the Chinese Pavilion, Ekerö Municipality, Sweden, designed by Carl Fredrik Adelcrantz, 1763–1769[35]

Neoclassicism and historicism

Excavations during the 18th century at Pompeii and Herculaneum, which had both been buried under volcanic ash during the 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius, inspired a return to order and rationality.[36] In the mid-18th century, antiquity was upheld as a standard for architecture as never before. Neoclassical architecture focused on Ancient Greek and Roman details, plain, white walls and grandeur of scale. Compared to the previous styles, Baroque and Rococo, Neoclassical exteriors tended to be more minimalist, featuring straight and angular lines, but being still ornamented.

Neoclassicism was the status quo from the mid to late 18th century, until the middle of the 19th. The transition from Rococo to Neoclassicism was not dramatic. The Louis XVI style in France shows clearly the strong interest of architects and designers for the volumes, proportions and motifs of ancient Greece and Rome, but their creations still have the aristocratic and cozy vibe of the Rococo. Similarly, some of the creations of Robert Adam, one of the most well known British architects who designed in the Neoclassical style, still have the delicacy of Rococo, like in the case of the Eating Room from the Osterley Park in London.

After the French Revolution, Neoclassical architecture and design advocated a return to austerity after the "excesses" of the Rococo and thus limited the use of mascarons. The Empire style of the First French Empire (1800-1815) didn't feature many mascarons, since they are rare in Ancient Greek and Roman architecture and design. The keystone often decorated in the past centuries was left empty at the beginning of the 19th century. The interest for Ancient Greece and Rome also led to an appetite for the Ancient Egypt. After the French campaign in Egypt and Syria, Egyptian art was brought to European collections, and the history, nature and life in Egypt were documented by scientists. Sometimes, Neoclassical buildings and designs mix Greco-Roman elements with Egyptian motifs.

In parallel with Neoclassicism, Romanticism was another movement that developed in the 18th century and that reached its peak in the 19th. Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism, as well as glorification of the past and nature, preferring the medieval to the classical. A mix of literary, religious, and political factors prompted late-18th and 19th century British architects and designers to look back to the Middle Ages for inspiration.[37] In France, Romanticism was not the key factor that led to the revival of Gothic architecture and design. Vandalism of monuments and buildings associated with the Ancien Régime (Old Regime) happened during the French Revolution. Because of this an archaeologist, Alexandre Lenoir, was appointed curator of the Petits-Augustins depot, where sculptures, statues and tombs removed from churches, abbeys and convents had been transported. He organized the Museum of French Monuments (1795-1816), and was the first to bring back the taste for the art of the Middle Ages, which progressed slowly to flourish a quarter of a century later. Mascarons are not very common in the Gothic Revival, since in the Middle Ages they were mainly present on corbels.[38]

Besides the Middle Ages, thanks to Romanticism, interest appeared for other periods too, like the Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo. Without a single overreaching authority in style, pluralism became widespread. The Gothic Revival coexisted with a revival of the Rococo and revivals of other historic styles, some being non-Western.

Louis XVI style mascaron-shaped handle of a vase, by Pierre-Philippe Thomire, c.1780, gilt-bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Louis XVI style mascaron-shaped handle of a vase, by Pierre-Philippe Thomire, c.1780, gilt-bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Neoclassical mascaron, most probably from a piece of furniture, late 18th–early 19th century, gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Neoclassical mascaron, most probably from a piece of furniture, late 18th–early 19th century, gilt bronze, Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Neoclassical secretary decorated with many mascarons, c.1804-1809, amboyna wood veneered on pine; gilt-bronze mounts, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Neoclassical secretary decorated with many mascarons, c.1804-1809, amboyna wood veneered on pine; gilt-bronze mounts, Metropolitan Museum of Art Neoclassical lion mascarons on the ceiling of the Salon Bleu, Château de Compiègne, Compiègne, France, unknown architect of painter, c.1810

Neoclassical lion mascarons on the ceiling of the Salon Bleu, Château de Compiègne, Compiègne, France, unknown architect of painter, c.1810.jpg.webp) Egyptian Revival mascaron with the face of goddess Hathor on the facade of the Foire du Caire building (Place du Caire no. 2), Paris, unknown architect, 1828

Egyptian Revival mascaron with the face of goddess Hathor on the facade of the Foire du Caire building (Place du Caire no. 2), Paris, unknown architect, 1828 Gothic Revival knight mascarons on a candle holder, c.1830-1850, patinated and gilt bronze, Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris

Gothic Revival knight mascarons on a candle holder, c.1830-1850, patinated and gilt bronze, Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris_04.jpg.webp) Rococo Revival mascaron on a vessel, unknown designer, probably produced by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, c.1860, porcelain, Salon des aides de camp, Château de Compiègne

Rococo Revival mascaron on a vessel, unknown designer, probably produced by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory, c.1860, porcelain, Salon des aides de camp, Château de Compiègne Neoclassical mascaron in a mosaic on a ceiling of the Palais Garnier, Paris, designed by Charles Garnier, 1860–1875[39]

Neoclassical mascaron in a mosaic on a ceiling of the Palais Garnier, Paris, designed by Charles Garnier, 1860–1875[39]_Le_Nouvel_Op%C3%A9ra_de_Paris_met_50_foto's_(serietitel)%252C_RP-F-2007-380-33.jpg.webp) Neoclassical mascarons in a round ceiling ornament that depicts the four cardinal points, designed by Charles Garnier, c.1860–1875

Neoclassical mascarons in a round ceiling ornament that depicts the four cardinal points, designed by Charles Garnier, c.1860–1875.jpg.webp) Rococo Revival mascaron on a fireplace in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, probably designed by Édouard André, c.1869-1875

Rococo Revival mascaron on a fireplace in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, probably designed by Édouard André, c.1869-1875 Neoclassical ox mascaron on the Halles centrales de Dijon, designed by Louis-Clément Weinberger, 1873-1875

Neoclassical ox mascaron on the Halles centrales de Dijon, designed by Louis-Clément Weinberger, 1873-1875.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Neoclassical skull mascaron on the tomb of the Dobre Nicolau Family, Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, Romania, designed by Thoma Dobrescu, c.1900

Neoclassical skull mascaron on the tomb of the Dobre Nicolau Family, Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest, Romania, designed by Thoma Dobrescu, c.1900.jpg.webp) Romanian Revival windows with mascarons at the top, on the facade of Strada Polonă no. 13, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1900

Romanian Revival windows with mascarons at the top, on the facade of Strada Polonă no. 13, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1900.jpg.webp)

Beaux Arts and Art Nouveau

The revivalism of the 19th century led in time to Eclecticism (mix of elements of different styles). Because architects usually revived Classical styles, most Eclectic buildings and designs have a distinctive look. In France, they were usually mixes of elements taken from the Renaissance until Napoleon (including Neoclassicism and its forms). The most famous building of this type is the Opéra Garnier in Paris, which combines for example double columns taken from Baroque with rooflines of mascarons and festoons taken from Neoclassicism, on the main facade. Alone, these elements are reminiscent of a specific period, but they are put together in a coherent and harmonious way. Many of the mascarons from Eclectic architecture and designs of the 19th and very early 20th centuries are inspired by those found in Baroque and Rococo, and just like in the 17th and 18th centuries, they are often on a keystone and in a cartouche.

The Belle Époque was a period that begun around 1871–1880 and that ended with the outbreak of World War I in 1914. It was characterized by optimism, regional peace, economic prosperity, colonial expansion, and technological, scientific, and cultural innovations. Eclecticism reached its peak in this period, with Beaux Arts architecture. The style takes its name from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where it developed and where many of the main exponents of the style studied. Buildings in this style often feature Ionic columns with their volues on the corner (like those found in French Baroque), a rusticated basement level, overall simplicity but with some really detailed parts, arched doors, and an arch above the entrance like the one of the Petit Palais in Paris. The style aimed for a Baroque opulence through lavishly decorated monumental structures that evoked Louis XIV's Versailles. Because of the ethereal vibe of the style, many Beaux Arts mascarons have a calm and confident expression, most of them being female. Male mascarons were also sometimes present in decoration, but usually as faces of Hermes, Poseidon or Hercules.

Besides Beaux Arts, another movement that was popular during the Belle Époque was Art Nouveau. Rejecting eclecticism, Art Nouveau was one of the first styles of Modernism. It had multiple versions in different countries. The Belgian and French form is characterized by organic shapes, ornaments taken from the plant world, sinuous lines, asymmetry (especially when it comes to objects design), the whiplash motif, the femme fatale, and other elements of nature. In Austria, Germany and the UK, it took a more stylized geometric form, as a form of protest towards revivalism and eclecticism. The geometric ornaments found in Gustav Klimt's paintings and in the furniture of Koloman Moser are representative of the Vienna Secession (Austrian Art Nouveau).[41] Art Nouveau mascarons consist often of faces of young women, showing the preference of many Art Nouveau artists for the femme fatale, a typology of the mysterious, beautiful, and seductive woman whose charms ensnare her lovers, often leading them into compromising, deadly traps. She is often shown as a creature of the night, fused with the natural world. Just like Beaux Arts ones, many Art Nouveau mascarons have calm and confident expressions. Some of the most impressive are found in jewelry. Art Nouveau mascarons were sometimes maximalist, the face having different accessories and/or foliage around it.

Beaux Arts polychrome mosaics with mascarons on the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Monaco, designed by Charles Garnier, 1879

Beaux Arts polychrome mosaics with mascarons on the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Monaco, designed by Charles Garnier, 1879 Beaux Arts mascaron of Avenue de l'Opéra no. 8, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1880

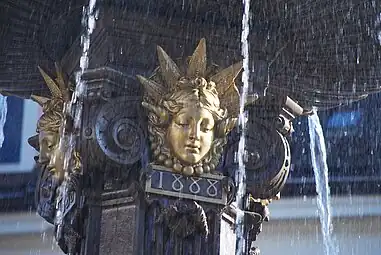

Beaux Arts mascaron of Avenue de l'Opéra no. 8, Paris, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1880 Beaux Arts mascaron of the Grande Fontaine (Avenue Léopold-Robert), La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, by Louis Maximilien Bourgeois, 1888

Beaux Arts mascaron of the Grande Fontaine (Avenue Léopold-Robert), La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, by Louis Maximilien Bourgeois, 1888.jpg.webp) Two Beaux Arts mascarons of Avenue Henri-Martin no. 87, Paris, designed by Albert Walwein, 1892

Two Beaux Arts mascarons of Avenue Henri-Martin no. 87, Paris, designed by Albert Walwein, 1892.jpg.webp) Beaux Arts mascaron on the Pont Alexandre III, Paris, designed by Joseph Cassien-Bernard and Gaston Cousin, 1896-1900

Beaux Arts mascaron on the Pont Alexandre III, Paris, designed by Joseph Cassien-Bernard and Gaston Cousin, 1896-1900 The three Secessionist gorgons on the Secession Building, Vienna, Austria, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, 1897-1898[42]

The three Secessionist gorgons on the Secession Building, Vienna, Austria, designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich, 1897-1898[42] Art Nouveau mascaron-shaped breast ornament, by René Lalique, 1898–1900, silver, email and alabaster, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, Germany

Art Nouveau mascaron-shaped breast ornament, by René Lalique, 1898–1900, silver, email and alabaster, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, Germany Stylized Art Nouveau mascaron of Casa Calvet (Carrer de Casp no. 48), Barcelona, Spain, designed by Antoni Gaudí, 1898-1900

Stylized Art Nouveau mascaron of Casa Calvet (Carrer de Casp no. 48), Barcelona, Spain, designed by Antoni Gaudí, 1898-1900 Beaux Arts mascaron under a balcony of the Cantacuzino Palace (Calea Victoriei no. 141), Bucharest, designed by Ion D. Berindey, 1898-1906[43]

Beaux Arts mascaron under a balcony of the Cantacuzino Palace (Calea Victoriei no. 141), Bucharest, designed by Ion D. Berindey, 1898-1906[43].jpg.webp) Beaux Arts mascaron in a small arabesque on the facade of Strada Clopotarii Vechi no. 4, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect, 1899-1900

Beaux Arts mascaron in a small arabesque on the facade of Strada Clopotarii Vechi no. 4, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect, 1899-1900 Giant Art Nouveau mascaron on a pavilion erected in the court of the Cotroceni Palace, Bucharest, unknown architect, 1901

Giant Art Nouveau mascaron on a pavilion erected in the court of the Cotroceni Palace, Bucharest, unknown architect, 1901

.jpg.webp) Beaux Arts mascaron on Rue de la Paix no. 23, Paris, unknown architect, 1908

Beaux Arts mascaron on Rue de la Paix no. 23, Paris, unknown architect, 1908 Art Nouveau capital with mascarons of the Printemps Haussmann (Boulevard Haussmann no. 64), Paris, designed by René Binet, 1911[44]

Art Nouveau capital with mascarons of the Printemps Haussmann (Boulevard Haussmann no. 64), Paris, designed by René Binet, 1911[44].jpg.webp) Beaux Arts mascaron with a multitude of flowers around it, above a window of the parfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain, (Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 68), Paris, designed by architect Charles-Frédéric Méwès and decorated by Bérard Christian, 1912[45]

Beaux Arts mascaron with a multitude of flowers around it, above a window of the parfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain, (Avenue des Champs-Élysées no. 68), Paris, designed by architect Charles-Frédéric Méwès and decorated by Bérard Christian, 1912[45].JPG.webp) Beaux Arts mascaron with lavander in its hair, above a window of the parfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain

Beaux Arts mascaron with lavander in its hair, above a window of the parfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain Beaux Arts mascaron with flowers in its hair, above the door of the perfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain

Beaux Arts mascaron with flowers in its hair, above the door of the perfumery of Jacques and Pierre Guerlain

Interwar period

Art Deco is a style created as a collective effort of multiple French designers to make a new modern style around 1910. It was obscure before WW1, but became very popular during the interwar period, being heavily associated with the 1920s and the 1930s. The movement was a blend of multiple characteristics taken from Modernist currents from the 1900s and the 1910s, like the Vienna Secession, Cubism, Fauvism, Primitivism, Suprematism, Constructivism, Futurism, De Stijl, and Expressionism. Because of this, mascarons are more angular and stylized, mask-like, clearly influenced by Cubism, a fine art movement with highly stylized and geometrized human figures, like those found in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon painted by Pablo Picasso. Painters, sculptors, designers and architects also found inspiration in non-Western regions, like East Asia, Pre-Columbian Americas or Sub-Saharian African art.[46] Art Deco had four phases: early, mature, late, and Streamline Moderne. The buildings of the 1910s and early 1930s are compositionally and stylistically similar with the Beaux-Arts ones from the 1900s and 1910s, but highly stylized and with a refined geometry. Pilasters and other Classical elements are used during this decade, but geometrized, together with simple floral motifs and abstract ornaments. An example of early Art Deco is the Central Social Insurance Company Building (now the Asirom Building) on Bulevardul Carol I, Bucharest, by Ion Ionescu, 1930s. Most Art Deco mascarons are present on early Art Deco buildings and designs. Mature Art Deco, highly associated with the 1930s, was more modern and exuberant compared to the early form. Stepped setbacks are a key feature of this period. Late Art Deco, from the late 1930s and the 1940s, paves the way for the International Style, but without completely abandoning ornamentation. More complex ornaments like mascarons or foliage disappear completely during this period, being seen as out of fashion. Facades with 90° angle corners and decorated minimally only with simple cornices at each level are key features of this phase. However, this doesn't mean that these buildings are banal or dull. Materials of bright colours were used inside, especially marble and granite, and the exteriors usually had lightning rods. At the same time, Streamline Moderne was also popular in the 1930s and 40s, characterized by rounded corners and overall dynamism.

Although Modernism was mainstream under the form of Art Deco during the interwar period, revivals of historic or local styles continued. In Romania for example, Mediterranean Revival architecture was one of the main styles of the 1930s, together with Art Deco and Romanian Revival (the national style). Of course, some of these styles used mascarons for ornamentation.

At the end of the interwar period, with the rise in popularity of the International Style, characterized by the complete lack of any ornamentation, led to the complete abandonment of any ornaments, including mascarons.

Art Deco mascaron of Avenue de Versailles no. 70-72, Paris, designed by Paul Delaplace and sculpted by Jean Boucher, 1928

Art Deco mascaron of Avenue de Versailles no. 70-72, Paris, designed by Paul Delaplace and sculpted by Jean Boucher, 1928 Art Deco mascaron on an unidentified building in Bordeaux, France, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1930

Art Deco mascaron on an unidentified building in Bordeaux, France, unknown architect or sculptor, c.1930.jpg.webp) Mediterranean Revival (late revivalism) lion mascarons above a series of window of Strada George Enescu no. 14, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1930

Mediterranean Revival (late revivalism) lion mascarons above a series of window of Strada George Enescu no. 14, Bucharest, unknown architect, c.1930.jpg.webp) Art Deco mascarons of the Palais de Chaillot, Paris, designed by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma, 1937[48]

Art Deco mascarons of the Palais de Chaillot, Paris, designed by Louis-Hippolyte Boileau, Jacques Carlu and Léon Azéma, 1937[48] Art Deco mascaron for a fountain, by Henri Navarre, 1937, glass, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris

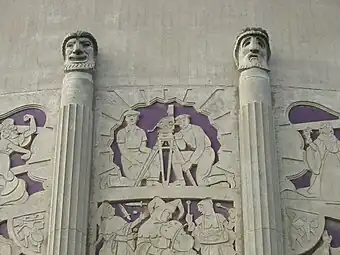

Art Deco mascaron for a fountain, by Henri Navarre, 1937, glass, Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris Art Deco mascarons on the King City High School Auditorium, King City, California, US, designed by Robert Stanton and Joseph Jacinto Mora, 1939

Art Deco mascarons on the King City High School Auditorium, King City, California, US, designed by Robert Stanton and Joseph Jacinto Mora, 1939.jpg.webp) Mediterranean Revival window of the Prof. C.A. Teodorescu House (Bulevardul Eroii Sanitari no. 89), Bucharest, designed by Ion Giurgea, 1941[49]

Mediterranean Revival window of the Prof. C.A. Teodorescu House (Bulevardul Eroii Sanitari no. 89), Bucharest, designed by Ion Giurgea, 1941[49]

Postmodernism

Postmodernism, a movement that questioned Modernism (the status quo after WW2), promoted the inclusion of elements of historic styles in new designs. An early text questioning Modernism was by architect Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), in which he recommended a revival of the 'presence of the past' in architectural design. He tried to include in his own buildings qualities that he described as 'inclusion, inconsistency, compromise, accommodation, adaptation, superadjacency, equivalence, multiple focus, juxtaposition, or good and bad space.'[50] Venturi encouraged 'quotation', which means reusing elements of the past in new designs. Part manifesto, part architectural scrapbook accumulated over the previous decade, the book represented the vision for a new generation of architects and designers who had grown up with Modernism but who felt increasingly constrained by its perceived rigidities. Multiple Postmodern architects and designers put simplified reinterpretations of the elements found in Classical decoration on their creations. However, they were in most cases highly simplified, and more reinterpretations than true reuses of the elements intended. Because of their complexity, mascarons were very rarely used in Postmodern architecture and design.[51]

.jpg.webp) Mascarons in cartouches spilling water in Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans, USA, by Charles Moore, 1978[53]

Mascarons in cartouches spilling water in Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans, USA, by Charles Moore, 1978[53] Mascaron with an Art Nouveau-inspired print on a Vans t-shirt, unknown fashion designer and illustrator, c.2021, print on textile

Mascaron with an Art Nouveau-inspired print on a Vans t-shirt, unknown fashion designer and illustrator, c.2021, print on textile

See also

Notes

- "mascaron". Oxford Reference. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- "BUCHAREST 1870S MASCARON". casedeepoca.com. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- "Art Nouveau in faces: fantasy world of 'New art'". essenziale-hd.com. May 29, 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- White, Ethan Doyle (2023). Pagans - The Visual Culture of Pagan Myths, Legends + Rituals. Thames & Hudson. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-500-02574-1.

- White, Ethan Doyle (2023). Pagans - The Visual Culture of Pagan Myths, Legends + Rituals. Thames & Hudson. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-500-02574-1.

- White, Ethan Doyle (2023). Pagans - The Visual Culture of Pagan Myths, Legends + Rituals. Thames & Hudson. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-500-02574-1.

- Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 136. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- "Bucranium". britannica.com. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- Irina Cios; Călin Demetrescu; Viorica Dene; Liviu Lăzărescu; Hortensia Masichievici; Adina Nanu; Ion Panaitescu; Amelia Pavel; Mircea Popescu; Carmen Răchițeanu; Tereza Sinigalia (1995). Dicționar de artă (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane. p. 79. ISBN 973-33-0268-6.

- Fabergé and the Russian Crafts Tradition - An Empire's Legacy. Thames & Hudson. 2017. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-500-48022-9.

- "Guéridon décoré de têtes de bélier, d'une paire avec OA 5231 BIS". collections.louvre.fr. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Wilkinson 1993, pp. 32, 83.

- Pinch 1993, pp. 135–139.

- Wilkinson, Toby (2008). Dictionary of ANCIENT EGYPT. Thames & Hudson. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-500-20396-5.

- "canopic jar; model". britishmuseum.org. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- Cole, Emily (2002). Architectural Details - A Visual Guide to 5000 Years of Building Styles. Ivy Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-78240-169-8.

- Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Room - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Room - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- BIRD - Exploring the Winged World. Phaidon. 2021. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-83866-140-3.

- Virginia, L. Campbell (2017). Ancient Room - Pocket Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-500-51959-2.

- Gray, George T. (2022). An Introduction to the History of Architecture, Art & Design. Sunway University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-967-5492-24-2.

- Fortenberry 2017, p. 71.

- Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- Irina Cios; Călin Demetrescu; Viorica Dene; Liviu Lăzărescu; Hortensia Masichievici; Adina Nanu; Ion Panaitescu; Amelia Pavel; Mircea Popescu; Carmen Răchițeanu; Tereza Sinigalia (1995). Dicționar de artă (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane. p. 277. ISBN 973-33-0268-6.

- Hubert Faensen, Vladimir Ivanov (1981). Arhitectura Rusă Veche (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane.

- "Eglise de la Trinité". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- "Eglise de la Trinité". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Hubert Faensen, Vladimir Ivanov (1981). Arhitectura Rusă Veche (in Romanian). Editura Meridiane.

- "Gouverneto Monastery". Explore Crete. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Gert Hirner, Jakob Murböck (1998). Wanderungen in Westkreta (in German). Bergverlag Rother. p. 22. ISBN 9783763342211. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Bailey 2012, pp. 279, 281.

- Bailey 2012, pp. 238.

- Hopkins 2014, p. 86.

- Hopkins 2014, p. 82.

- "Kina slott, Drottningholm". www.sfv.se. National Property Board of Sweden. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Hodge 2019, p. 31.

- The Architecture Book - Big Ideas Simply Explained. DK. 2023. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-2414-1503-0.

- M. Jallut, C. Neuville (1966). Histoire des Styles Décoratifs (in French). Larousse. p. 37.

- Jones 2014, p. 296.

- "Restaurare sediu UNNPR". uar-bna.ro. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- Hopkins 2014, p. 140, 143.

- Jones 2014, p. 323.

- Mariana Celac, Octavian Carabela and Marius Marcu-Lapadat (2017). Bucharest Architecture - an annotated guide. Ordinul Arhitecților din România. p. 90. ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- Schwartzman, Arnold (2023). Art Nouveau - The World's Most Beautiful Buildings from Guimard to Gaudi. p. 40. ISBN 9781786750631.

- "Immeuble". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Criticos, Mihaela (2009). Art Deco sau Modernismul Bine Temperat - Art Deco or Well-Tempered Modernism (in Romanian and English). SIMETRIA. pp. 66, 68, 69, 70, 77, 87. ISBN 978-973-1872-03-2.

- "PSS / 41, avenue Montaigne". pss-archi.eu. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- Larbodière, Jean-Marc (2015). L'Architecture de Paris des Origins à Aujourd'hui (in French). Massin. p. 164. ISBN 978-2-7072-0915-3.

- Ghigeanu, Mădălin (2022). Curentul Mediteraneean în arhitectura interbelică. Vremea. p. 360. ISBN 978-606-081-135-0.

- Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 660. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- Hopkins 2014, p. 200, 203.

- Hopkins, Owen (2020). Postmodern Architecture - Less is a Bore. Phaidon. p. 169. ISBN 978 0 7148 7812 6.

- Hodge 2019, p. 47.

References

- Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2012). Baroque & Rococo. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-5742-8.

- Hodge, Susie (2019). The Short Story of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7862-7370-3.

- Hopkins, Owen (2014). Architectural Styles: A Visual Guide. Laurence King. ISBN 978-178067-163-5.

- Jones, Denna, ed. (2014). Architecture The Whole Story. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29148-1.

- Pinch, Geraldine (1993). Votive Offerings to Hathor. Griffith Institute. ISBN 978-0900416545.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (1993). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500236635.