Millefleur

Millefleur, millefleurs or mille-fleur (French mille-fleurs, literally "thousand flowers") refers to a background style of many different small flowers and plants, usually shown on a green ground, as though growing in grass. It is essentially restricted to European tapestry during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, from about 1400 to 1550, but mainly about 1480–1520. The style had a notable revival by Morris & Co. in 19th century England, being used on original tapestry designs, as well as illustrations from his Kelmscott Press publications. The millefleur style differs from many other styles of floral decoration, such as the arabesque, in that many different sorts of individual plants are shown, and there is no regular pattern. The plants fill the field without connecting or significantly overlapping. In that it also differs from the plant and floral decoration of Gothic page borders in illuminated manuscripts.

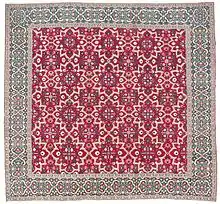

There is also a rather different style known as millefleur in Indian carpets from about 1650 to 1800.

In the 15th century, an elaborate glass making technique was developed. See Millefiori, Murano glass and other glassmakers make pieces, particularly paper weights, that use the motif.[1][2]

Tapestries

In the millefleur style the plants are dispersed across the field on a green background representing grass, to give the impression of a flowery meadow, and cover evenly the whole decorated field. At the time they were called verdures in French. They are mostly flowering plants shown as a whole, and in flower, with the coloration of the flowers of a distinct brightness compared to the usually darker background. Many are recognizable as specific species, with varying degrees of realism, but accuracy does not seem to be the point of the depiction. Neither are the flowering plants used to create perspective or depth of field. There are very often animals and sometimes human figures dispersed around the field, often rather small in relation to the plants, and at a similar size to each other, whatever their relative sizes in reality.

The tapestries usually include large figures whose meaning is not always apparent, which seems to derive from the division of labour under the guild system, so that the weavers were obliged to repeat figure designs by members of the painters' guild, but could design the backgrounds themselves. Such was the case in Brussels at any rate, after a lawsuit between the two groups in 1476.[3] The subjects are generally secular, but there are some religious survivals.[4]

Millefleur style was most popular in late 15th and early 16th century French and Flemish tapestry, with the best known examples including The Lady and the Unicorn and The Hunt of the Unicorn. These are from what has been called the "classic" period, where each "bouquet" or plant is individually designed, improvised by the weavers as they worked, while later tapestries, probably mostly made in Brussels, usually have mirror images of plants on the right and left sides of the piece, suggesting a cartoon re-used twice. The precise origin of the pieces has been much argued about, but the only surviving example whose original payment can be traced was a large heraldic millefleur carpet made for Duke Charles the Bold of Burgundy in Brussels, part of which is now in the Bern Historical Museum.[5]

The beginnings of the style may be seen in earlier tapestries. The famous Apocalypse Tapestry series (Paris, 1377–82) has several backgrounds covered in vegetal motifs, but these are springing from tendrils in the way of illuminated manuscript borders. In fact most of the very large sets do not fully use the style, with the meadow of flowers extending right to the top of the picture space. The early Devonshire Hunting Tapestries (1420s) have naturalistic landscape backgrounds, seen from a somewhat elevated viewpoint, so that the lower two-thirds or so of each scene has a millefleur background, but this gives way to forest or sea and sky at the top of the tapestry. The Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald (about 1450) and most of The Hunt of the Unicorn set (about 1500) are similar. From the main period, each tapestry in The Lady and the Unicorn set has three distinct zones of millefleur background: the island containing the figures, where the plants are densely arranged, an upper background zone where they are arranged in vertical bands, and accompany animals at very varied scales, and a lower zone where a single row of plants have slight gaps between them.

During the 1800s, the millefleur style was revived and incorporated into numerous tapestry designs by Morris & Co. The company's Pomona (1885) and The Achievement of the Grail (1895–96) tapestries demonstrate an adherence to the medieval millefleur style. Other tapestries such as their The Adoration of the Magi (1890) and The Failure of Sir Gawain (c. 1890s) use the style more liberally, borrowing the flowers' often flat, splayed appearance, but overlapping them and using them as part of a landscape and not as a purely decorative backdrop. The Adoration of the Magi was one of the company's most popular designs, with ten versions woven between 1890 and 1907.

_Mon_seul_d%C3%A9sir_(La_Dame_%C3%A0_la_licorne)_-_Mus%C3%A9e_de_Cluny_Paris.jpg.webp) À mon seul désir, from the set The Lady and the Unicorn, late 15th century

À mon seul désir, from the set The Lady and the Unicorn, late 15th century 15th-century tapestry

15th-century tapestry Detail of one of the set The Lady and the Unicorn

Detail of one of the set The Lady and the Unicorn Millefleurs in a heraldic tapestry for the Bishop of Salzburg, after 1519

Millefleurs in a heraldic tapestry for the Bishop of Salzburg, after 1519 The Adoration of the Magi woven by Morris & Co in the late 1800s.

The Adoration of the Magi woven by Morris & Co in the late 1800s.

Indian carpets

The term is also used to describe north Indian carpets, originally of the late Mughal era in the late 17th and 18th century. However these have large numbers of small flowers in repeating units, often either springing unrealistically from long-ranging twisting stems, or arranged geometrically in repeating bunches or clusters. In this they are essentially different from the irregularly arranged whole plant style of European tapestries, and closer to arabesque styles. The flowers springing from the same stem may be of completely different colours and types. There are two broad groups, one directional and more likely to show whole plants (an early version is the upper illustration), and one not directional and often just showing stems and flowers.[6]

They appear to have been manufactured in Kashmir and present-day Pakistan. They reflect a combination of European influences and underlying Persian-Mughal decorative tradition, and a trend for smaller elements in designs.[7] The style, or styles, were later adopted by Persian weavers, especially for prayer rugs, up to about 1900.

Millefiori decoration uses the Italian version of the same word, but is a different style, restricted to glass.

India, Fragment of a Saf Carpet, an early example rather closer to the tapestry style

India, Fragment of a Saf Carpet, an early example rather closer to the tapestry style Millefleur 'Star-Lattice' carpet, 17th–early 18th century Mughal India, Christie's

Millefleur 'Star-Lattice' carpet, 17th–early 18th century Mughal India, Christie's

Other appearances

The millefleur style is sometimes used liberally in Sir Edward Burne-Jones' illustrations for the Kelmscott Press publications, such in as his frontispiece to The Wood Beyond the World (1894).

Millefleur are used in artist Leon Coward's mural The Happy Garden of Life which appeared in the 2016 sci-fi movie 2BR02B: To Be or Naught to Be. The flowers in the mural were adapted and redesigned from those in The Unicorn in Captivity from The Hunt of the Unicorn tapestry series, as part of the mural's religious allusions.[8]

See also

- Mille Fleur is a breed of Belgian chicken.

Notes

- Egglezos, Panos (January 31, 2012). "How It's Made - Millefiori Glass Paperweights" (Video). How It's Made. Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved March 21, 2019 – via YouTube.

- Struble, Karen. "Millefleur glass paperweight ...and more!". Retrieved March 21, 2019 – via Pinterest.

- Souchal, 108

- Souchal, 117

- Souchal, 108

- Walker, 119–125

- Walker, 119–125

- Masson, Sophie (October 19, 2016). "2BR02B: the journey of a dystopian film–an interview with Leon Coward". Feathers of the Firebird (Interview).

References

- Souchal, Geneviève (ed.), Masterpieces of Tapestry from the Fourteenth to the Sixteenth Century: An Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1974, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Galeries nationales du Grand Palais (France), ISBN 0870990861, 9780870990861, google books

- Walker, Daniel (1997). Flowers underfoot : Indian carpets of the Mughal era. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Further reading

- Cavallo, Adolph S., Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), ISBN 0870996444, 9780870996443