Sheldon tapestries

Sheldon tapestries were produced at Britain's first large tapestry works in Barcheston, Warwickshire, England, established by the Sheldon family. A group of 121 tapestries dateable to the late 16th century were produced. Much the most famous are four tapestry maps illustrating the counties of Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Oxfordshire and Warwickshire, with most other tapestries being small furnishing items, such as cushion covers. The tapestries are included in three major collections: the Victoria and Albert Museum, London;[1] the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York;[2] and the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, Scotland (still uncatalogued). Pieces were first attributed in the 1920s to looms at Barcheston, Warwickshire by a Worcestershire antiquary, John Humphreys, without clear criteria;[3] on a different, but still uncertain basis, others were so classified a few years later.[4] No documentary evidence was then, or is now, associated with any tapestry, so no origin for any piece is definitely established.[5]

.JPG.webp)

The Sheldon Tapestry Maps

These are the four tapestry-woven maps commissioned in the late 1580s by Ralph Sheldon (1537–1613), based on the county surveys of Christopher Saxton. The tapestries illustrated the counties of Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Warwickshire and Oxfordshire, with each tapestry portraying one county. Designed to hang together in Ralph Sheldon's home in Weston, near Long Compton, Warwickshire, they would have presented a view across central England, from the Bristol Channel to London, covering the counties where Sheldon’s family and friends held land. The maps are important in showing the landscape of central England in the 16th century, at a time when modern map making was in early development.[6] Of the original four tapestries, three survive in part and only the Warwickshire one is still complete, now displayed at Market Hall Museum, Warwick.

Background

In 1570 Ralph Sheldon's father, William, laid out plans which would, if successful, set up a new tapestry-weaving business in his manor house at Barcheston, Warwickshire. A Flemish tapestry maker, Richard Hyckes, lived there rent-free on condition that he organised the weaving of tapestries and textiles. At the same time Hyckes was working, with the title of arras-maker, in the Great Wardrobe in London, part of the household departments of Queen Elizabeth I. He was head of the team responsible for the care and repair of the 2,500 tapestries inherited from her father King Henry VIII.[7] Ralph Sheldon allowed the business to continue following his father's death; he subsequently commissioned the tapestry maps, though there is no proof that they were woven in Warwickshire. It has been suggested that the size of this project would have required more space and skilled labour than would have been available in Barcheston at that time.[8]

During the English Civil War the Sheldon family supported the Royalist cause, and after the war their lands were confiscated. With the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and accession of King Charles II, their lands were returned to them and a second Ralph Sheldon, known as ‘the Great’ (1623–1684) commissioned copies of two of the earlier tapestries, those of Oxfordshire and Worcestershire, possibly because the originals had been damaged.[9] Instead of the detailed imagery of the Elizabethan borders on the four originals these tapestries were woven with a stylised picture frame and classical decorations. The original 16th-century border on the Warwickshire map was also replaced in the same style, probably at this time.

Design

Each of the four tapestry maps measured approximately 20 feet (6.1 m) wide and 13 feet (4.0 m) high and was based on the recent county maps made by Christopher Saxton, which provided information on rivers, towns, and geographical features such as woods and forests. Each tapestry focussed on a single county and the area of tapestry around that county boundary was filled in with details taken from the appropriate adjoining Saxton county maps. To enable the central county to stand out on each tapestry, it was given a pale background and a red border, while the backgrounds of neighbouring counties were woven in contrasting shades. Because it bordered so many other counties, the Oxfordshire tapestry, for instance, included details from nine of Saxton's maps.

The tapestry designer had to greatly enlarge the scale since the counties on the Saxton printed maps measured approximately 12 by 10 inches (30 by 25 cm).[10] The tapestries therefore had space to add more detail than Saxton’s maps, so they include more natural and man-made features of each area, vary the species and style of trees and size of hills and illustrate items such as fire beacons and windmills. Most villages were drawn in a similar style, as houses grouped around a central church, though towns are more varied and shown in more detail so may have been based on more accurate drawings. Coventry was depicted with many church spires surrounded by its defensive walls, and Worcester included the stone-arched bridge over the River Severn. All settlements, whatever their size, were identified in black capital letters on a pale background.

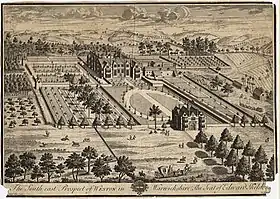

Numerous private houses were shown, often depicted in detail and indicating the building style of the house. Most had a connection with Sheldon’s family and friends and the Warwickshire tapestry included Coughton Court, home of Sheldon's wife, as well as the Sheldon properties in Weston, Skiltes and Beoley. Because of the overlap of geographical areas, each of the four tapestries was able to include Sheldon’s house in Weston which, unlike most of the other houses which were surrounded by fencing, was shown bordered by a hedge.

Every tapestry had the arms of Queen Elizabeth in the upper left corner, a panel of text inspired by William Camden's Britannia in the upper right and a scale and dividers in the lower left corner.

Each right-hand corner of the tapestry had a coat of arms, representing different generations of the Sheldon family. Gloucestershire shows the arms of Ralph Sheldon (d. 1613) and Anne Throckmorton, Warwickshire shows those of Edward Sheldon (d.1643) and his wife Elizabeth Markham, while the simple Sheldon coat seen on Oxfordshire may represent their son William, born early in 1589. The Elizabethan Worcestershire tapestry lacks its right-hand side so that the arms are missing, but when it was woven a second time it showed those of William Sheldon (d.1570) and his wife Anne Willington. The 17th-century Oxfordshire map carries the arms of Ralph 'the Great' Sheldon and his wife Henrietta Maria Savage.[11]

Each tapestry was then surrounded by a decorated border approximately 18 inches (46 cm) deep, which included representations of allegorical and classical figures as well as pieces of text referring to the county depicted.[12] The orientation of the four tapestries is not the same. The tapestry maps of Worcestershire and Oxfordshire have north at the top, while Warwickshire and Gloucestershire were made with north to the left.

Dispersal

The tapestries remained in the house and in 1738 George Vertue recorded that he had seen the Elizabethan maps and later copies of Oxfordshire and Worcestershire hanging together in the Great Drawing Room in Weston. Thirty years later in 1768 Walpole saw only ‘Three large maps of Counties in tapestry’.[13] In 1781 when the contents of the house were sold, only three pieces were listed, by size, in the entries in Christie's auction catalogue.[14][15]

The three tapestries listed are identifiable as the 16th-century Warwickshire map with its 17th-century border and the two 17th-century copies of Oxfordshire and Worcestershire; they were bought by Horace Walpole. He later gave them to Lord Harcourt, who left them to the Archbishop of York and in 1827 they were given to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society who put them on display.[16] In 1897 the Warwickshire tapestry was lent to the new Birmingham museum at its opening, and in 1914 the tapestries were exhibited at an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Because the border around the Warwickshire map had been replaced in the 17th century, it had been assumed that the whole map had also been made at that time.[17] In 1980 a study of the tapestry revealed that the border had been stitched to the tapestry and not woven with it; this meant that the centre of the tapestry was older, revealing that the Warwickshire map dated from the 16th century and so was the only one of the original four tapestries which was still complete.[18] Cleaning and conservation of the Warwickshire tapestry was carried out in 2011, prior to its temporary exhibition at the British Museum in 2012. During this treatment the lining was removed from the back where some fragments of the Elizabethan original were found. The original colours could also be seen, bright green and yellow, though on the front of the tapestry these have now faded to blue.[19] Cleaning also highlighted previously hidden details like the many cottages hidden among the trees of the Forest of Arden and the stone circle near Great Rollright, possibly the earliest depiction of the Rollright Stones, Neolithic and Bronze Age megaliths on the Oxford- and Warwickshire border.[20]

The Warwickshire tapestry contains a woven date, 1588. It was perhaps meant to commemorate the marriage of Edward Sheldon and Elizabeth Markham in that year, rather than being date the tapestry was woven.

Current locations

The history of the three 16th-century maps is more complicated. They were not identifiably listed in the sale catalogue of 1781; probably already damaged, the tapestries of Worcestershire, Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire were acquired by different owners by unknown means. The antiquarian Richard Gough donated large sections of the Worcestershire and Oxfordshire and smaller fragments of the Gloucestershire tapestries to the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford in 1809. In 2007, the Bodleian Library acquired a further piece of the Gloucestershire tapestry map, costing over £100,000.[21][22] This, with a companion piece, had first come to light in the 1860s[23] and re-emerged in 1914;[24] they decorated a fire screen. So too did two other parts of the 16th-century Oxfordshire tapestry; they had been in the possession of Horace Walpole and were sold from Strawberry Hill House in 1842.[25] they were donated in 1954 to the Victoria and Albert Museum.[26]

In 1960, the three complete tapestries were sold at Sotheby's, London. Worcestershire was bought by the Victoria and Albert Museum,[27] the Oxfordshire tapestry was bought by a private buyer and is now on display at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.[28] The Warwickshire tapestry was bought for the Warwickshire Museum Service and is now displayed in the Market Hall Museum, Warwick.[29]

References

- Wingfield-Digby, G., The Victoria and Albert Museum, Catalogue of Tapestries Medieval and Renaissance, London 1980, pg.71-83.

- Standen, E.A., European post-medieval Tapestries and Related Hangings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1985, nos. 119-124.

- Humphreys, J., 'Elizabethan Sheldon Tapestries', Archaeologia 74, 1924, pg. 181-202, reprinted as a monograph with the same title, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1929

- Barnard, E.A.B. and Wace, A.J.B., ‘The Sheldon tapestry weavers and their work’, Archaeologia 78, 1928, pg. 255-314

- Turner, H.L., "Tapestries once at Chastleton House and their influence on the image of the tapestries called Sheldon: a re-assessment", The Antiquaries Journal, vol. 88, 2008, pg. 313-343, also available on-line.

- "The newly acquired Sheldon Tapestry Map goes on display". Bodleian Libraries. University of Oxford. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- Campbell, T.P. Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Yale University Press, 2007.

- Turner, No Mean Prospect: Ralph Sheldon's Tapestry Maps, pg. 38-39

- Turner, No Mean Prospect, pg. 44

- Turner, No Mean Prospect, pg. 10-18

- Tapestry Maps Portfolio, no author, Victoria and Albert Museum, London c. 1915.

- Turner, pg. 30-34

- Walpole’s Journal, Walpole Soc Annual XVI, 1927-28

- Christie and Ansell 1781, Sale Catalogue of the property of William Sheldon, Weston, August 28-September 11, 1781

- Turner, Hilary. "The Tapestries called Sheldon" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- Turner, pg. 46-48

- Turner, pg. 47

- Turner, H.L. "The Sheldon Tapestry Map of Warwickshire", Warwickshire History, vol. 12 2002, pg 32-44.

- Wood, Maggie (July 26, 2012). "The tale of a tapestry". The British Museum. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Sharpe, Emily (30 August 2012). "Ancient stones revealed on tapestry". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Renaissance Tapestry Maps reunited after more than a century". Bodleian Libraries. University of Oxford. 21 June 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- "Making History 06/10/2009". BBC Radio 4. 6 October 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Notes and Queries, Jan-June 1869, 4th series, 606, 540, 428

- Wingfield-Digby, Catalogue 1981, p. 69.

- Sale Catalogue, Strawberry Hill 1842, day 17, lot 59 and later in the catalogue of a Bristol bookseller called Strong;

- Wingfield-Digby, Catalogue 1981, p. 67.

- "Tapestry". Victoria & Albert museum. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- Turner, Hilary (2006). "Oxfordshire in wool and silk: Ralph Sheldon the Great's tapestry map of Oxfordshire" (PDF). Oxoniensia, Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "The Sheldon Tapestry Maps". Warwickshire Heritage and Culture. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

Bibliography

- Turner, Hilary (2010). No Mean Prospect: Ralph Sheldon's Tapestry Maps. The Plotwood Press. ISBN 978 0 9529920 11.