Mamluk architecture

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style that developed under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk sultans were prolific patrons of architecture and contributed enormously to the fabric of historic Cairo.[1] The Mamluk period, particularly in the 14th century, oversaw the peak of Cairo's power and prosperity.[2] Their architecture also appears in cities such as Damascus, Jerusalem, Aleppo, Tripoli, and Medina.[3]

_-_Egypt-13A-061_(cropped).jpg.webp)   Top: Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan in Cairo, Egypt (1356–1361); Centre: Mausoleum of Sultan Qalawun in Cairo (1285); Bottom: Citadel of Qaitbay in Alexandria, Egypt (late 15th century) | |

| Years active | 1250–1517 (combined with other styles after 1517) |

|---|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Major Mamluk monuments typically consisted of multi-functional complexes which could combine various elements such as a patron's mausoleum, a madrasa, a khanqah (Sufi lodge), a mosque, a sabil, or other charitable functions found in Islamic architecture. These complexes were built with increasingly complicated floor plans which reflected the need to accommodate limited urban space as well as a desire to visually dominate their urban environment. Their architectural style was also distinguished by increasingly elaborate decoration, which began with pre-existing traditions like stucco and glass mosaics but eventually favoured carved stone and marble mosaic paneling. Among the most distinguished achievements of Mamluk architecture were their ornate minarets and the carved stone domes of the late Mamluk period.[4][5][1]

While the Mamluk empire was conquered by the Ottomans in 1517, Mamluk-style architecture continued as a local tradition in Cairo which was blended with new Ottoman architectural elements.[6] In the late 19th century, "Neo-Mamluk" or Mamluk Revival buildings began to be built to represent a form of national architecture in Egypt.[7][8]

History

The Mamluks were a military corps recruited from slaves that served under the Ayyubid dynasty and eventually took over from that dynasty in 1250, ruling over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz until the Ottoman conquest of 1517. Mamluk rule is traditionally divided into two periods: the Bahri Mamluks (1250–1382) of Kipchak origin from southern Russia, named after the location of their barracks on the sea, and the Burji (1382–1517) of Circassian origin, who were quartered in the Citadel. However, Mamluk architecture is oftentimes categorized more by the reigns of major sultans, than a specific design.[4] Caroline Williams, in her guide to the historic monuments of Cairo, suggests dividing the history of Mamluk architecture in the city in three approximate phases: Early Mamluk (1250–1350), Middle Mamluk (1350–1430), and Late Mamluk (1430–1517).[9]

Bahri Mamluk period

Despite their military character, the Mamluks were also prolific builders and left a rich architectural legacy throughout Cairo and in other major cities of their empire.[10] Continuing a practice started by the Ayyubids, much of the land occupied by former Fatimid palaces in Cairo was sold and replaced by newer buildings, becoming a prestigious site for the construction of Mamluk religious and funerary complexes.[11] Construction projects initiated by the Mamluks pushed the city outward while also bringing new infrastructure to the centre of the city.[12]

The end of the Ayyubid period and the start of the Mamluk period were marked by creation of the first multi-purpose funerary complexes in Cairo. The last Ayyubid sultan, al-Salih Ayyub, founded the Madrasa al-Salihiyya in 1242. His wife, Shajar ad-Durr, added his mausoleum to it after his death in 1249, and then built her own mausoleum and madrasa complex in 1250 at another location south of the Citadel.[13] These two complexes were the first in Cairo to combine a founder's mausoleum with a religious and charitable complex, which would come to characterize the nature of most Mamluk royal foundations afterward.[13][14] The early Mamluk period that followed became an era of architectural experimentation, during which some trends of later Mamluk architecture began to develop.[15] For example, by the late Bahri period entrance portals had developed into the distinctive tall, recessed portals with muqarnas ("stalactite" sculpting) canopies that remained common until the end of the Mamluk sultanate. Architects also experimented with the placement of different elements of a building complex (like the domed mausoleum chamber or the minaret) in order to enhance the visual impact of their monuments in an urban setting.[15]

The defeat of the Mongols and of the last Crusader states in the Levant in the second half of the 13th century resulted in a relatively long period of peace within the Mamluk empire, which in turn brought economic prosperity.[16] One of the most important architectural achievements of this period is the funerary complex of al-Mansur Qalawun (who reigned between 1279 and 1290), which was built in 1284–1285 over the remains of a former Fatimid palace at Bayn al-Qasrayn, in the heart of the city.[17] The enormous complex included his monumental mausoleum, a madrasa, and a large hospital (maristan). The hospital, one of the most important medical centres in the Islamic world of this era, continued to operate until the late Ottoman period.[17] During the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad (1293–1341, with interregnums), Qalawun's grandson, Cairo reached its apogee in terms of population and wealth.[18] He was one of the most prolific patrons of architecture in Mamluk history. Under his reign Cairo expanded in multiple directions and new districts, such al-Darb al-Ahmar and the area below and west of the Citadel, filled up with palaces and religious foundations built by his emirs (Mamluk commanders and officials). Al-Nasir Muhammad also carried out some of the most significant works inside the Citadel, erecting a new mosque, a palace, and a grand domed throne hall known as the Great Iwan.[19]

After al-Nasir Muhammad's death (1341), Cairo was hit by the Black Death (1348) and the sultanate underwent prolonged political instability up until the early 15th century.[20] Despite this, the largest and most ambitious Mamluk religious building, the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan, was constructed during this period. Craftsmen were recruited from many regions of the Mamluk empire to work on the highly costly project, which may account for the apparent influence of Iranian (Ilkhanid) and Anatolian Seljuk architecture in some elements of the building. The complex was left partly unfinished after the death of the founder, al-Nasir Hasan, in 1361.[21][22] After this, other notable Mamluk complexes from the late Bahri period in Cairo include the Sultaniyya Mausoleum and the Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha'ban.

- Bahri Mamluk architecture

%252C_Syria_-_Burial_chamber_mihrab_looking_southwest_-_PHBZ024_2016_1317_-_Dumbarton_Oaks_(edited).jpg.webp) Mihrab of the Mausoleum of Sultan Baybars in Damascus (built 1277–1281), with marble and glass mosaics

Mihrab of the Mausoleum of Sultan Baybars in Damascus (built 1277–1281), with marble and glass mosaics Complex of Qalawun in Cairo (built in 1284–85). It included a mausoleum, a madrasa, and a maristan (hospital).[23]

Complex of Qalawun in Cairo (built in 1284–85). It included a mausoleum, a madrasa, and a maristan (hospital).[23] Courtyard of the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad (built in 1318 and modified in 1335) at the Citadel of Cairo

Courtyard of the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad (built in 1318 and modified in 1335) at the Citadel of Cairo Entrance portal of the Mosque of Ahmad al-Mihmandar (1325), built by one of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad's emirs

Entrance portal of the Mosque of Ahmad al-Mihmandar (1325), built by one of Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad's emirs

Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha'ban (1368–1369); the two domes correspond to mausoleum chambers

Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Sha'ban (1368–1369); the two domes correspond to mausoleum chambers

Burji Mamluk period

The Burji Mamluk sultans followed the artistic traditions established by their Bahri predecessors. The architecture of the early Burji period continued the style of the late Bahri period.[26] Though the plagues returned frequently throughout the 15th century, Cairo remained a major metropolis and its population recovered in part through rural migration. More conscious efforts were conducted by rulers and city officials to redress the city's infrastructure and cleanliness.[27] Some Mamluk sultans in this period, such as Barbsay (r. 1422–1438) and Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496), had relatively long and successful reigns.[28]: 183, 222–230 At the beginning of the Burji period, Barquq (r. 1382–1399, with interruption) built his own major funerary complex at Bayn al-Qasrayn, which resembled the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan in many ways, although much smaller.[26][29] After him, the funerary complex of Faraj ibn Barquq (his son), is one of the most accomplished monuments of this period. This foundation also kickstarted the development of the Northern Cemetery of Cairo as a Mamluk necropolis.[30][31] In the late 14th and early 15th centuries, stone-built minarets became increasingly refined and stone domes (instead of wood or brick domes) became widespread. The domes also started to be carved with simple decorative motifs. The "sabil-kuttab" (a combination of sabil at ground level and primary school on an upper level) started to appear as a common element of religious complexes.[32]

In the late Mamluk period new complexes were generally more restrained in size and were given increasingly complicated and irregular layouts, as architects had to contend with the limited spaces available to build in crowded cities.[33] After al-Nasir Muhammad, Qaytbay was one of the most prolific patrons of art and architecture of the Mamluk era. He built or restored numerous monuments in Cairo, in addition to commissioning projects beyond Egypt.[28]: 223 [34] During his reign, the shrines of Mecca and Medina were extensively restored and new monuments were built in Jerusalem.[35][36] In Cairo, the funerary complex of Qaytbay was one of the most celebrated monuments of Mamluk architecture.[37] His reign also saw the peak of artistic quality in the decorative arts, such as the stone-carved decoration of domes.[38] Building continued under the last Mamluk sultan, Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghuri (r. 1501–17), who commissioned his own complex (1503–5) and conducted a major reorganization and reconstruction of the Khan al-Khalili district.[39] This last period also saw renewed experimentation in the shape of minarets, sometimes returning to prototypes used in earlier monuments.[38]

_-_Madrasa_of_Sultan_al-Zahir_Barquq_(14803204015).jpg.webp) Prayer hall of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (built between 1384 and 1386) in Cairo

Prayer hall of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (built between 1384 and 1386) in Cairo Mosque of al-Utrush in Aleppo (1410), an example of provincial Mamluk architecture

Mosque of al-Utrush in Aleppo (1410), an example of provincial Mamluk architecture Interior of a mausoleum in the Khanqah-Mosque of Faraj ibn Barquq (built between 1400 and 1411) in the Northern Cemetery of Cairo

Interior of a mausoleum in the Khanqah-Mosque of Faraj ibn Barquq (built between 1400 and 1411) in the Northern Cemetery of Cairo Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh (built between 1415 and 1420), with its mausoleum dome visible

Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh (built between 1415 and 1420), with its mausoleum dome visible Complex of Sultan Qaytbay (1474) in the Northern Cemetery of Cairo

Complex of Sultan Qaytbay (1474) in the Northern Cemetery of Cairo Complex of Sultan al-Ghuri (1505), a two-part building with a madrasa on one side and a khanqah and mausoleum on the other

Complex of Sultan al-Ghuri (1505), a two-part building with a madrasa on one side and a khanqah and mausoleum on the other

Ottoman period

In 1517 the Ottoman conquest of Egypt formally brought Mamluk rule to an end, although Mamluks themselves continued to play a prominent role in local politics.[40] In architecture, some new structures were subsequently built in the classical Ottoman architectural style. The Sulayman Pasha Mosque from 1528 is an example of this. However, many new buildings were still built in the Mamluk style up until the 18th century (e.g. the Sabil-Kuttab of Abd ar-Rahman Katkhuda[41]), albeit with some elements borrowed from Ottoman architecture, and, conversely, new buildings constructed with an overall Ottoman form often borrowed details from Mamluk architecture (e.g. the Sinan Pasha Mosque[42]). Some building types from the late Mamluk period, such as sabil-kuttabs (a combination of sabil and kuttab) and multi-storied caravanserais (wikalas or khans), actually grew in number during the Ottoman period. Changes in the Ottoman architecture in Egypt include the introduction of pencil-shaped minarets from the Ottomans and domed mosques which gained dominance over the hypostyle mosques of the Mamluk period.[43][44][1]

Mosque of Mahmud Pasha (1568)

Mosque of Mahmud Pasha (1568) Details inside the Sinan Pasha Mosque (1571)

Details inside the Sinan Pasha Mosque (1571)

Neo-Mamluk architecture

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a "Neo-Mamluk" style was also used in Egypt, which emulated the forms and motifs of Mamluk architecture but adapted them to modern architecture. Patrons and governments favoured it partly as a nationalist response against Ottoman and European styles and a concordant effort to promote local "Egyptian" styles (though the architects were sometimes Europeans).[7][8][45] Examples of this style are the Museum of Islamic Arts in Cairo, the Al-Rifa'i Mosque, the Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi Mosque in Alexandria, and numerous private and public buildings such as those of Heliopolis.[7][8][45][46]

Characteristics

Overview

Mamluk architecture is distinguished by the construction of multi-functional buildings whose floor plans became increasingly creative and complex due to the limited available space in the city and the desire to make monuments visually dominant in their urban surroundings.[4][1][5] Expanding on the Fatimid Caliphate's development of street-adjusted mosque façades, the Mamluks developed their architecture to enhance street vistas, positioning major elements in a deliberate way to be clearly visible by passersby.[47] While the organization of Mamluk era monuments varied, the funerary dome and minaret were constant themes. These attributes are prominent features in a Mamluk mosque's profile and were significant in the beautification of the city skyline. In Cairo, the funerary dome and minaret were respected as symbols of commemoration and worship.[48] One aspect of Mamluk design was the intentional juxtaposition of the round dome, the vertical minaret, and the tall façade walls of the building, which architects placed in differing arrangements in order to maximize the visual impact of a building in its specific urban environment.[49] Patrons also prioritized the placement of their mausoleum next to both the prayer hall inside and the street outside, so that those walking by or offering prayers could easily see the tomb through the windows.[50][51]

Mamluk buildings could include a single mausoleum or a small charitable building (e.g. a public drinking fountain), while larger architectural complexes typically combined many functions into one or more buildings. These could include charitable functions and social services, such as a mosque, khanqah (Sufi lodge), madrasa, bimaristan (hospital), maktab or kuttab (elementary school), sabil (kiosk for dispensing free water), or hod (drinking trough for animals); or commercial functions, such as a wikala or khan (a caravanserai to house merchants and their goods) or a rabʿ (a Cairene apartment complex for renters).[4][1]

Among other developments, during the Mamluk period the cruciform or four-iwan floorplan was adopted for madrasas and became more common for new monumental complexes than the traditional hypostyle mosque, although the vaulted iwans of the early period were replaced with flat-roofed iwans in the later period.[52][53] Monumental decorated entrance portals became common compared to earlier periods, often carved with muqarnas and covered in other decorative schemes.[15] Vestibule chambers behind these were sometimes covered with ornate vaulted ceilings in stone. The vestibule of the Madrasa of Uljay al-Yusufi (circa 1373) features the first ornate groin vault ceiling of its kind in Mamluk architecture and variations of this feature were repeated in later monuments.[54]

- Architectural types and elements

Example of portal, façade, dome, and minaret visually juxtaposed along a main street in Cairo (Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi, circa 1481)

Example of portal, façade, dome, and minaret visually juxtaposed along a main street in Cairo (Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi, circa 1481) Example of a sabil (below) and a kuttab (above) integrated into the street façade of a complex (Complex of Sultan al-Ghuri, circa 1505)

Example of a sabil (below) and a kuttab (above) integrated into the street façade of a complex (Complex of Sultan al-Ghuri, circa 1505) Example of a Mamluk mosque in the traditional hypostyle form, the al-Maridani Mosque (1340)

Example of a Mamluk mosque in the traditional hypostyle form, the al-Maridani Mosque (1340).jpg.webp) Example of the cruciform four-iwan layout in the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1386)

Example of the cruciform four-iwan layout in the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1386) Example of monumental entrance portal at the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1386)

Example of monumental entrance portal at the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1386) Earliest example of ornate groin vault, in the vestibule of the Madrasa of Uljay al-Yusufi (1373)

Earliest example of ornate groin vault, in the vestibule of the Madrasa of Uljay al-Yusufi (1373)

Decoration

The decoration of monuments also became more elaborate as the Mamluk period progressed. In the Bahri Mamluk period carved stucco was widely used in interiors and on the exterior of brick domes and minarets. Glass mosaics, while present in early Mamluk monuments, were discontinued in the late Bahri period.[15][55] Ablaq masonry (masonry with alternating layers of coloured stone) was also commonly used and is recorded in some of Baybars' early monuments, such as the Qasr Ablaq (Ablaq Palace) that he built for himself in Damascus (no longer extant).[56] Some of the stucco decoration in early monuments appears to be influenced by the stucco decoration of other regions, and may have involved craftsmen recruited or imported from these regions. The fine stucco mihrab of the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, for example, resembles contemporary Iranian stuccowork under the Ilkhanids in artistic centers like Tabriz. The rich stuccowork on that same building's minaret, on the other hand, appears to include Andalusi or Maghrebi craftsmanship alongside local Fatimid motifs.[57][58][59]

- Stucco decoration

Stucco decoration in the former vestibule of the Sultan Qalawun's mausoleum (1285)

Stucco decoration in the former vestibule of the Sultan Qalawun's mausoleum (1285) Stucco-carved mihrab in the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad (1304)

Stucco-carved mihrab in the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad (1304) Stucco decoration on the minaret of the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad (1304)

Stucco decoration on the minaret of the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad (1304) Stucco decoration around the dome of the Madrasa of Sunqur Sa'di (circa 1321)

Stucco decoration around the dome of the Madrasa of Sunqur Sa'di (circa 1321) Kufic Arabic inscription carved in stucco, Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361)

Kufic Arabic inscription carved in stucco, Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361)

Over time, especially as stone construction replaced brick, stone carving and colored marble mosaics or paneling became the dominant decorative methods.[15][55] These were used on walls and for the pavement of floors. Influences from the Syrian region and possibly even Venice were evident in these trends.[15] The motifs themselves include geometric patterns and vegetal arabesques, along with bands and panels of calligraphy in floriated Kufic, Square Kufic, and Thuluth scripts.[60] In religious structures, the mihrab (a concave wall niche symbolizing the direction of prayer) was often the focus of internal decoration. The "conch" (concave part) of the mihrab niche was frequently decorated with a radiating "sunrise" motif.[61] The "blazon" of the founder was sometimes included in varying locations amongst the decoration, but this was not a consistent feature of all buildings. A Mamluk blazon was typically a roundel which contained a calligraphic rendition of the sultan's name and title.[62]

- Stone and marble decoration

Stone with inlaid mosaic decoration in the Mausoleum of Sultan Qalawun (1285), including Square Kufic motifs

Stone with inlaid mosaic decoration in the Mausoleum of Sultan Qalawun (1285), including Square Kufic motifs Mihrab with central "sunrise" motif and glass mosaics in the spandrels above, at the Taybarsiyya Madrasa (1304) at Al-Azhar Mosque

Mihrab with central "sunrise" motif and glass mosaics in the spandrels above, at the Taybarsiyya Madrasa (1304) at Al-Azhar Mosque Marble and stone-paneled mihrab and wall of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361)

Marble and stone-paneled mihrab and wall of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361) Example of marble mosaic pavement in the Madrasa of Sultan Barquq (1386)

Example of marble mosaic pavement in the Madrasa of Sultan Barquq (1386) Stone-carved and marble mosaic decoration above an entrance of the Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi (1481)

Stone-carved and marble mosaic decoration above an entrance of the Mosque of Qijmas al-Ishaqi (1481) Blazon of Qaytbay carved onto the drum of his mausoleum dome (c. 1474)

Blazon of Qaytbay carved onto the drum of his mausoleum dome (c. 1474)_DSCF4628.jpg.webp) Stone carving on the minaret of Qaytbay (1495) at the Al-Azhar Mosque

Stone carving on the minaret of Qaytbay (1495) at the Al-Azhar Mosque Calligraphic dado of marble inlaid with black paste in the Madrasa-Mosque of al-Ghuri (1505)

Calligraphic dado of marble inlaid with black paste in the Madrasa-Mosque of al-Ghuri (1505)

Wood was used throughout the Mamluk era, although it became harder to procure in the late period. Wooden ceilings had painted and gilded decoration that resembled book illumination of the same period.[63] Minbars (pulpits), the only major furniture in mosques, were also usually ornate works of wood-carving and inlaid decoration featuring geometric motifs.[63] The doors of religious monuments were typically sheeted with bronze which was fashioned into geometric patterns as well. The richest examples are the doors of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan; those of its entrance were appropriated and moved to al-Mu'ayyad's mosque afterwards, but the doors of the mausoleum, which are also inlaid with floral patterns in silver and gold, remain in their original place.[63]

- Wood and metal decoration

Painted and gilded wooden ceiling in the Sabil-Kuttab of Sultan Qaytbay (1479)

Painted and gilded wooden ceiling in the Sabil-Kuttab of Sultan Qaytbay (1479) Wooden minbar gifted to the Mosque of al-Salih Talai by Baktimur al-Jugandar circa 1300; one of the oldest surviving Mamluk minbars[64]

Wooden minbar gifted to the Mosque of al-Salih Talai by Baktimur al-Jugandar circa 1300; one of the oldest surviving Mamluk minbars[64] Details on the wooden Minbar of al-Ghamri (circa 1451)

Details on the wooden Minbar of al-Ghamri (circa 1451).jpg.webp) The bronze and silver-inlaid doors of the mausoleum of Sultan Hasan (mid-14th century)

The bronze and silver-inlaid doors of the mausoleum of Sultan Hasan (mid-14th century) Bronze-plating decoration on the doors of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1384)

Bronze-plating decoration on the doors of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Barquq (1384)

Minarets

Mamluk minarets became very ornate and usually consisted of three tiers separated by balconies, with each tier having a different design than the others, a characteristic which was generally unique to Cairo.[65] Early Bahri minarets were more often built in brick, but some, like the minarets of Qalawun's complex and of al-Nasir Muhammad's mosque, were built in stone. From the 1340s onward stone minarets became more common and eventually were the standard.[65] In Mamluk constructions the masons who built the minarets were – at least in some cases – different from the masons who built the rest of the building, as evidenced by the signatures of the masons on certain monuments. As a result, the builders of minarets were probably specialized in this task and were able to experiment on their own more than the builders of the main structure.[65]

Minarets in the Bahri period initially continued the trend of earlier Fatimid and Ayyubid minarets, with square shafts ending in a lantern structure – known as a mabkhara ("incense burner") – topped by a fluted dome.[66][67] This is evident in the large minaret of Qalawun's complex (1285), although the top of this minaret was rebuilt later and no longer preserves its summit.[68][69] The minarets of the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar al-Jawli (1303) and of the Madrasa of Sunqur Sa'di (circa 1315), are better-preserved and have a similar style, except that their shape is more slender and the shaft of the second tier is octagonal, prefiguring later changes.[66][67] The minaret of the al-Maridani Mosque (circa 1340) is the first one to have an entirely octagonal shaft and the first one to end with a narrow lantern structure consisting of eight slender columns topped by a bulbous stone finial. This style of minaret later became the basic standard form of minarets, while the makhbara-style minaret disappeared in the second half of the 14th century.[70][67][65]

Later Mamluk minarets in the Burji period most typically had an octagonal shaft for the first tier, a round shaft on the second, and a lantern structure with finial on the third level.[51][71] The stone-carved decoration of the minaret also became very extensive and varied from minaret to minaret. Minarets with completely square or rectangular shafts reappeared at the very end of the Mamluk period during the reign of Sultan al-Ghuri (r. 1501–1516). During al-Ghuri's reign the lantern summits were also doubled – as with the minaret of the Mosque of Qanibay Qara or al-Ghuri's minaret at the al-Azhar Mosque – or even quadrupled – as with the original minaret of al-Ghuri's madrasa.[71][65] A double lantern summit had previously appeared in one of the original minarets of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan in the mid-14th century, but was not repeated until this late period.[72] (Unfortunately, the original minaret of Sultan Hasan collapsed in the 17th century and the top of al-Ghuri's quadruple-lantern minaret collapsed in the 19th century; both were reconstructed in slightly simpler styles, as they appear today.[73])

- Mamluk minarets

The minaret of Sultan Qalawun's complex, originally built in 1285. The third level was rebuilt in brick by his son in 1303. The conical cap is from Ottoman repairs centuries later.[68]

The minaret of Sultan Qalawun's complex, originally built in 1285. The third level was rebuilt in brick by his son in 1303. The conical cap is from Ottoman repairs centuries later.[68] Minaret of the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar (1303), with an example of the mabkhara-style summit

Minaret of the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar (1303), with an example of the mabkhara-style summit Minaret of Amir el-Maridani Mosque (1340), the earliest example of the style which was repeated in later minarets

Minaret of Amir el-Maridani Mosque (1340), the earliest example of the style which was repeated in later minarets Twin minarets of Bab Zuweila, built between 1415 and 1420 for the nearby Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh

Twin minarets of Bab Zuweila, built between 1415 and 1420 for the nearby Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh Minaret of the Madrasa-Mosque of al-Ashraf Barsbay (1425)

Minaret of the Madrasa-Mosque of al-Ashraf Barsbay (1425) Minaret of the Funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (1474)

Minaret of the Funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (1474).jpg.webp) Minaret of the Mosque of Qanibay Qara (1503), with a rectangular shaft and double lantern summit

Minaret of the Mosque of Qanibay Qara (1503), with a rectangular shaft and double lantern summit

Domes

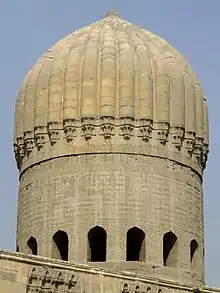

According to scholar Doris Behrens-Abouseif, the evolution of Mamluk domes followed similar trends to that of minarets but happened at a slower pace.[74] Mamluk domes transitioned over time from wooden or brick structures to stone masonry structures. On the interior, the transition between the base of the round dome and the walls of the square chamber below were initially accomplished through multi-tiered squinches and later with muqarnas-carved pendentives.[67][75] Early domes in the Bahri period were hemispherical but slightly pointed and can be sorted into two general types: a dome with a short drum whose curvature begins immediately at its base and whose surface was usually plain (e.g. like the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir), or a tall dome whose curvature begins closer to the top and is frequently ribbed (e.g. the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar).[75] Many of these Mamluk wooden and brick domes collapsed and/or were rebuilt in subsequent centuries due to neglect, structural instability, or earthquakes. Some examples of reconstruction include the domes of the Mausoleum of Sultan Hasan, the Mausoleum of Sultan Barquq, the mausoleum in the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, the dome of the al-Nasir Muhammad Mosque at the Citadel, and even the much later brick dome of the Mausoleum of al-Ghuri (which was finally demolished in the 19th century and never rebuilt).[4][1]

A number of wood or brick domes in the Bahri period were double-shelled domes (meaning an outer dome built over an inner dome) and had a bulbous or bulging profile which resembles that of later Timurid domes. Examples of this include the dome of the Mausoleum of Sarghitmish (which was rebuilt in the 19th century), the twin domes of the Sultaniyya Mausoleum, and the original dome of Sultan Hasan's mausoleum (which later collapsed and was rebuilt in a different shape).[76] These domes may have been inspired by Iranian domes of either the Ilkhanid or Jalayirid periods.[77][76] However, it is difficult to establish a chronological line of influences due to the lack of surviving precedents in other regions.[77][76] Doris Behrens-Abouseif has argued that the bulbous dome shape may be a local Cairene innovation which was combined with the tradition of Iranian double-shelled domes.[76]

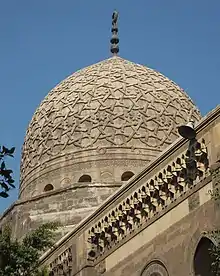

Later domes in the Burji period were more strongly pointed and had tall drums. Stone domes were progressively given more detailed surface decoration, starting with simple motifs like "chevron" patterns and eventually culminating with complex geometric or arabesque motifs in the late Mamluk period.[75][69] The large stone domes of the twin mausoleums in the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq (built between 1400 and 1411) were an important step in the development of stone domes and a high point of Mamluk engineering. They are the first large domes in Cairo to be built in stone[78] and they remain the largest stone domes of the Mamluk period in Cairo, with a diameter of 14.3 meters.[79][80] The peak of ornamental stone dome architecture was achieved under the reign of Qaytbay in the late 15th century, as seen at his funerary complex in the Northern Cemetery.[81][82]

- Mamluk domes

_DSCF4051.jpg.webp) Ribbed domes of the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar (1303)

Ribbed domes of the Mausoleum of Salar and Sanjar (1303)_(cropped)_DSCF5884.jpg.webp) Plain dome of the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir (1310)

Plain dome of the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir (1310) Bulbous dome at the Sultaniyya Mausoleum (circa 1350s)

Bulbous dome at the Sultaniyya Mausoleum (circa 1350s)_(cropped)_DSCF8212.jpg.webp) Dome of the Mosque of Aytimish al-Bajasi (1383)

Dome of the Mosque of Aytimish al-Bajasi (1383) One of the mausoleum domes of the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq (circa 1411)

One of the mausoleum domes of the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq (circa 1411).jpg.webp) Stone dome with carved chevron pattern (Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad, 1420)

Stone dome with carved chevron pattern (Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad, 1420) Interior of al-Mu'ayyad's dome, with example of muqarnas-carved pendentives

Interior of al-Mu'ayyad's dome, with example of muqarnas-carved pendentives Stone dome with carved geometric pattern (Mausoleum of Sultan Barsbay, circa 1432)

Stone dome with carved geometric pattern (Mausoleum of Sultan Barsbay, circa 1432).jpg.webp) Stone dome with superimposed geometric and floral motifs at the Funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (completed in 1474)

Stone dome with superimposed geometric and floral motifs at the Funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay (completed in 1474) Stone dome with arabesque motifs (Mosque of Qanibay Qara, 1503)

Stone dome with arabesque motifs (Mosque of Qanibay Qara, 1503)

Portals

Mamluk entrance portals were a prominent part of the façade and were heavily decorated, similar to other architectural traditions in the Islamic era. However, the overall façade of a building was often composed of other elements such as windows, a sabil and maktab, and general decoration, which attenuated the prominence of the entrance portal in comparison to other architectural styles like those of Syria.[83] The portals of the Bahri period were varied in their designs. Some, like that of Qalawun's complex (1285) and Sanjar and Salar's Mausoleum (1303), were decorated with features like marble paneling but were not architecturally emphasized in their proportions or position in the overall façade of the building.[83] By contrast, the most monumental and impressive portal of the Bahri era belongs to the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir (1310).[83]

Portals were often recessed into the façade and ended in an ornate stone-carved canopy above. Among other variations, a common design for the canopy in the mid-14th century was muqarnas vaulting, or a semi-dome above a muqarnas zone.[83][84] The use of muqarnas canopies in portals was initially a feature more characteristic of Damascus, where it was common in Ayyubid monuments, but it spread to Cairo in the 14th century.[85] An unusual flat muqarnas canopy was used in several monuments around the 1330s such as the Mosque of Amir Ulmas (1330) and the Palace of Bashtak (1339).[83] The massive entrance portal of the Madrasa-Mosque of Sultan Hasan (1356-1361) has an overall design that is strongly reminiscent of Anatolian Seljuk portals like the 13th-century Gök Medrese in Sivas. The portal's decoration, which was left unfinished in parts, also includes motifs of Chinese origin (which had also been present in earlier Mamluk art objects).[86][24] It has a grand muqarnas canopy. Other portals around the same period or shortly after, such as the entrance of the Madrasa of Sarghitmish (1356) and the Madrasa of Umm Sultan Sha'ban (1368), have a narrower pyramidal muqarnas vault canopy that is also similar to Anatolian Seljuk or Ilkhanid designs. The muqarnas portal of the Madrasa of Umm Sultan Sha'ban, however, is the last major example of this kind in the Mamluk period.[87]

In the 15th century, during the Burji period, portals that were mostly decorated with muqarnas became less common. The main entrance portal of the Mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh (built between 1415 and 1420) was also the last truly monumental portal built in the Mamluk period.[88] After this, portals with a "trilobed" profile and groin vaulting – typically a semi-dome above two other quarter-domes that resembled squinches – became the main theme. Some of these incorporated muqarnas into the squinches as well. This composition was also later adopted for the interior pendentives of domes, which may indicate parallel developments between portal architecture and dome architecture.[89] The most impressive groin vault portal was the gate of Bab al-Ghuri built in 1511 at Khan al-Khalili.[55]

- Mamluk portals

Entrance of Sultan Qalawun's complex (1285), with ablaq decoration

Entrance of Sultan Qalawun's complex (1285), with ablaq decoration_DSCF9254.jpg.webp) Portal of the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir (1310)

Portal of the Khanqah of Baybars al-Jashankir (1310).jpg.webp) Example of portal topped by a semi-dome with muqarnas under it, at the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad (1318 and 1335)

Example of portal topped by a semi-dome with muqarnas under it, at the Mosque of al-Nasir Muhammad (1318 and 1335) Portal of the Palace of Amir Qawsun: the inner portal with semi-dome and muqarnas dates from 1337, while the muqarnas canopy above dates from Qaytbay's reign (1468–1496)[90][91]

Portal of the Palace of Amir Qawsun: the inner portal with semi-dome and muqarnas dates from 1337, while the muqarnas canopy above dates from Qaytbay's reign (1468–1496)[90][91] Entrance portal with flat muqarnas canopy at the Mosque of Amir Ulmas al-Hajib (1330)

Entrance portal with flat muqarnas canopy at the Mosque of Amir Ulmas al-Hajib (1330) Massive portal of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361)

Massive portal of the Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (1356–1361) Pyramidal muqarnas canopy, along with ablaq, marble mosaic, and carved stone decoration, in the portal of the Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Shaban (1368)

Pyramidal muqarnas canopy, along with ablaq, marble mosaic, and carved stone decoration, in the portal of the Madrasa of Umm al-Sultan Shaban (1368) Entrance portal of the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh (1420)

Entrance portal of the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh (1420) Trilobed entrance portal with groin vaults at the Funerary complex of Barsbay (1432)

Trilobed entrance portal with groin vaults at the Funerary complex of Barsbay (1432) Trilobed entrance portal with groin vaults and muqarnas at the Funerary complex of Qaytbay (1474)

Trilobed entrance portal with groin vaults and muqarnas at the Funerary complex of Qaytbay (1474).jpg.webp) Elaborate groin vault gateway built by Sultan al-Ghuri at the Khan el-Khalili (1511)

Elaborate groin vault gateway built by Sultan al-Ghuri at the Khan el-Khalili (1511)

Apartment complexes

Multi-story buildings occupied by rental apartments, known as a rab' (plural ribā' or urbu), became common in the Mamluk period and continued to be a feature of the city's housing during the later Ottoman period.[92][93] This type of housing was a relatively unique to Cairo at the time. These apartments were often laid out as multi-story duplexes or triplexes. They were sometimes attached to caravanserais (wikalas) where the two lower floors were for commercial and storage purposes and the upper floors above were rented out to tenants. Even in the case of these wikala-rab' combinations, the apartment complexes had their own street entrances separate from the commercial complex below.[92] The oldest partially-preserved example of this type of structure is the Wikala of Amir Qawsun, which was built before 1341, but multiple later examples have survived from later centuries, either as part of caravanserais or as independent buildings.[92][93] Residential buildings in Cairo were in turn organized into close-knit neighbourhoods called a harat, which in many cases had gates that could be closed off at night or during disturbances.[93]

Role of architectural patronage

The patrons of architecture during the Mamluk period included both the sultans themselves and their mamluk amirs (commanders and high-ranking officials). Mamluk architectural complexes and their institutions were protected by waqf agreements, which gave them the status of charitable endowments or trusts which were legally inalienable under Islamic law. This allowed the sultan's legacy to be assured through his architectural projects, and his tomb – and potentially the tombs of his family – was typically placed in a mausoleum attached to his religious complex. Since charity is one of the fundamental pillars of Islam, these charitable projects publicly demonstrated the sultan's piousness, while madrasas in particular also linked the ruling Mamluk elite with the ulama, the religious scholars who also inevitably acted as intermediaries with the wider population.[4] Such projects helped confer legitimacy to the Mamluk sultans (rulers), who lived apart from the general population and were Ajam, of slave origin (mamluks were purchased and brought as young slaves then emancipated to serve in the military or government). Their charitable constructions strengthened their symbolic role as pious protectors of orthodox Sunni Islam and as sponsors of ṭuruq (Sufi brotherhoods) and of the local shrines of saints.[4]

Additionally, the provisions of the pious endowments also served the role of providing a financial future for the sultan's family after his death, as the Mamluk Sultanate was non-hereditary and the sultan's sons only rarely succeeded in taking the throne after his death, and rarely for long.[2][5] The sultan's family and descendants could benefit by retaining control of the various waqf establishments he built, and by legally retaining a part of the revenues from those establishments as tax-free income, all of which could not, in theory, be annulled by the regimes of subsequent sultans. As such, the building zeal of the Mamluk rulers was also motivated by very real pragmatic benefits, as recognized by some contemporary observers like Ibn Khaldun.[4]

Mamluk architecture beyond Cairo

Throughout the Mamluk period, Cairo remained by far the most important center of architectural patronage, as befitting its central political role as capital and economic role as a center of trade and craftsmanship. Partly as a result of this, the architecture and craftsmanship of monuments outside Cairo also rarely matched that of Cairo itself.[94] For most of the Mamluk period, the sultans rarely sponsored religious complexes or other non-military works outside Cairo.[95] There were exceptions, most notably Sultan Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496), who sponsored new religious and charitable constructions in several cities beyond Cairo.[96][34] He even sent craftsmen from Egypt in order to reproduce the architectural style of Cairo in these locations.[34] The sultans did regularly maintain or restore major religious sites such as the Haram al-Sharif (Temple Mount) in Jerusalem and the mosques of Medina and Mecca.[95] Most provincial monuments were instead commissioned by local Mamluk governors and amirs, or sometimes by wealthy local merchants.[95]

Beyond Cairo and Egypt, the major urban centres of the empire were located in Greater Syria. Aleppo, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Tripoli all contain numerous Mamluk-era monuments to this day. In the Syrian region, local architecture remained relatively conservative, largely perpetuating the established architectural traditions that existed under the earlier Ayyubid dynasty with regards to the style of domes, minarets, and other distinctive elements. The entrance portals were often the most impressive elements, while minarets, by contrast with Cairo, were less monumental and less ornate.[97] Mamluk monuments in Syria, like those of Cairo, were essentially funerary monuments centered on the mausoleum of the founder. As in Cairo, the mausoleum chamber was usually positioned next to the street so as to be highly visible. Compared to Cairo, however, these funerary complexes were smaller in scale and their facilities or accommodations were not as extensive as those of the capital.[97]

Damascus

Damascus had its own architectural traditions and the established Ayyubid style continued to be heavily influential during the Mamluk period. As Damascus was the "second city" of the Mamluk sultanate, it was one of the most patronized cities outside of Cairo.[98][10] Although many of the Mamluk buildings from this era have been damaged or only partly preserved, the city still contains the second-highest concentration of Mamluk monuments after Cairo.[99] Early Mamluk structures continued the established local tradition of flamboyant stonework and muqarnas portals, which eventually spread to Mamluk architecture in Cairo in the 14th century.[85]

The Citadel of Damascus, where the Mamluk garrison had held out, was demolished during the events of the Mongol invasion in 1260, but the rest of the city fared better than Aleppo, which was severely damaged by the invasion.[100] During the early Mamluk period Damascus prospered and international trade increased.[101] Baybars, who took power shortly after the defeat of the Mongols, spent much time in Damascus during his military campaigns in the region. He commissioned the creation of a great palace in the city, the Qasr al-Ablaq (Ablaq Palace), designed by the architect Ibrahim ibn Gana'im. The palace no longer survives today.[102] The same architect also designed Baybars' mausoleum and madrasa, which was commissioned after his death by his son, Baraka Khan, in 1277. The madrasa and mausoleum was added to an existing house that Saladin had lived in as a child.[102][103]: 48 The most notable feature of the new mausoleum is its decoration, which includes a dado of marble mosaics, a frieze of carved stucco at eye-level, and above this an extensive zone of glass mosaics that recall the mosaics of the Umayyad period in the city's Great Mosque. The mausoleum was not completed until 1281, during the reign of Qalawun.[103]: 48

Tankiz al-Nasiri, the Mamluk amir who governed Syria for 28 years (1312–1340) during al-Nasir Muhammad's reign, commissioned a major mosque in 1317.[98][104] It is located just west of the Citadel. At the time of its construction, it was the second-largest mosque in the area of Damascus after the Great Mosque.[98] The mosque was damaged and then largely demolished in the mid-20th century; only the minaret, the entrance portals, and Tankiz's attached mausoleum have been preserved.[98] Tankiz also restored and improved much of the city's infrastructure and built other monuments. His palace, no longer extant, was located on the same site as the present-day Azm Palace.[104] He also built a madrasa on the south side of this palace which still serves as a school today, preserving a finely-crafted muqarnas entrance portal.[105]

Madrasas were already an established feature of Damascus and the Mamluks built new ones while also restoring or expanding old ones. A total of 78 madrasas existed in the city during the Mamluk period, in addition to two other madrasas reserved for women.[106] Madrasas were often combined with the tombs of their founders to form religious-funerary complexes, as in Cairo. Prestigious Funerary monuments continued to be built in the established necropolis of al-Salihiyah, northwest of the walled city, but new funerary complexes also began to be built around the area of al-Midan in the early 14th century.[107] The latter area stretched along the road towards Mecca and it also contained exercise fields and training grounds for the Mamluks. Its northern section was enclosed by a wall in 1291. The southernmost area of construction in the Midan was known as Qubaybat ("little domes"), due to the large number of domed tombs. At the time, this area was mostly rural but today most of it has been overtaken with modern constructions. Only a few Mamluk-era monuments remain there today, including the al-Karimi or al-Dakak Mosque (1318), the Madrasa Qunshliya (1320), and the Mausoleum of Altunbugha (1329).[108] One of the most impressive Mamluk buildings from the 14th century, the Madrasa al-'Ajami, was built by a local businessman before or around 1348. It is located along a main street just outside the southwestern wall of the city. Its street façade demonstrates a more complete integration of contemporary Mamluk decoration with the local Damascus traditions, featuring decorative multi-coloured stonework and a tall recessed portal with a muqarnas canopy.[109] Caravanserais were also built in the city during the Mamluk period. Only two remain today: the Khan al-Dikka, which is only partly preserved, and the Khan Jaqmaq, which was first built in 1418 but then rebuilt in 1601 during the Ottoman period.[110]

One of the worst episodes of destruction occurred in 1401 when Timur (Tamerlane) sacked the city during his invasion of Syria. The city (and the wider empire) only recovered under the more stable rule of Barsbay. During the late Mamluk period new monuments were more often built outside the walled city, where more space was available to build. One major mosque from Barsbay's time is the Mosque of Khalil al-Tawrizi (or al-Tawrizi Mosque), built in 1420–1423 to the southwest of the city.[111][112] Around the same time, in 1418–1420, the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya was built on the orders of the Mamluk governor, Sayf al-Din Jaqmaq al-Arghunshawi (the future Sultan Jaqmaq), over the ruins of an older school destroyed in 1401.[112][113]: 114 Both the al-Tawrizi Mosque and the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya are the first religious monuments in Damascus to forego the traditional open courtyard layout and to adopt the Cairene layout with a "covered" or roofed courtyard and a projecting tomb chamber.[114][112] The Madrasa al-Sabuniyya, built in 1459–1464, is one of the most impressive late Mamluk monuments in the city, built by Ahmad ibn al-Sabuni. Located near the Madrasa al-'Ajami, it also has similar stonework decoration.[95][10][113]: 125 Qaytbay's contribution to the city includes the addition of a third minaret to the old Great Mosque in 1482–1488.[115]

- Mamluk architecture in Damascus

Al-Karimi Mosque (1318, possibly with later renovations)

Al-Karimi Mosque (1318, possibly with later renovations) Al-Sanjakdar Mosque, built by a Mamluk governor in 1347–1349

Al-Sanjakdar Mosque, built by a Mamluk governor in 1347–1349 Entrance portal of the Madrasa al-'Ajami (c. 1348)

Entrance portal of the Madrasa al-'Ajami (c. 1348) Entrance portal of the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya (1418–1420, restored in 20th century)

Entrance portal of the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya (1418–1420, restored in 20th century) Interior of the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya (1418–1420, restored in 20th century)

Interior of the Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya (1418–1420, restored in 20th century) Exterior of the Madrasa al-Sabuniyya (1459–1464)

Exterior of the Madrasa al-Sabuniyya (1459–1464) Entrance portal of Madrasa al-Sabuniyya (1459–1464)

Entrance portal of Madrasa al-Sabuniyya (1459–1464)_5179.jpg.webp) Minaret of Qaytbay at the Great Mosque of Damascus (1482–1488)

Minaret of Qaytbay at the Great Mosque of Damascus (1482–1488)

Aleppo

Aleppo suffered from the Mongol invasions of 1260 but progressively recovered afterwards. The early years of Mamluk rule in the city were occupied by repairs and restorations.[116] The city walls were extended further east, which opened up new space for future constructions. In the early 14th century some Mamluk governors commissioned mausoleums for themselves, but few major monuments were built in this early period.[116] One interesting monument is the Mehmendar Mosque (1302), whose round minaret (departing from the Ayyubid tradition of square minarets) is carved in a style reminiscent of Artuqid, Seljuk or Ilkhanid architecture.[116] Another religious construction, the Mosque of Ala al-Din Altunbugha al-Nasiri, was built in 1318 and is still mostly Ayyubid in style except for the more elaborate entrance portal and minaret.[116] The 1354 establishment of the Maristan of Arghun al-Kamil or Maristan Arghuni, a large bimaristan (hospital) for the mentally ill, was the most significant creation of the early Mamluk period in the city. It was composed of six units, each devoted to different types of treatment, arranged around three internal courtyards.[116][47] Its doorway, however, was likely reused from an earlier Ayyubid building.[116]

Towards the late 14th century Aleppo's prosperity increased more definitively as silk road trade routes were diverted through it, turning it into an entrepot for eastern caravans from Iran and Venetian merchants from the west.[117] Among the numerous monuments surviving from this period are the Mosque of Mankalibugha al-Shamsi (circa 1367), notable for its tall minaret, the Tawashi Mosque (1372), notable for its stone-carved details, and the al-Bayadah Mosque (1378), notable for its long street façade decorated with ablaq masonry and muqarnas carvings above the recessed windows.[116] Monumental entrance portals with muqarnas carvings became a standard feature of Mamluk architecture in the city, and stonemasons experimented with new decorative ideas and flourishes. The prosperity is also reflected in the increased attention to city's souks or markets. Previously, markets were organized in a grid-like pattern of streets but contained no formal architecture to house the shops. Some market streets were covered with wooden roofs. In the Mamluk period, however, some souk streets were covered with vaulted roofs of stone for the first time and stone booths for shops were built at regular intervals along them.[116] Caravanserais (khans) were also established in growing numbers. Hammams or public bathhouses also grew in number. The largest historic hammam in Syria today is the Yalbugha Hammam in Aleppo, originally built by the Mamluk governor Yalbugha al-Nasiri in 1389 and rebuilt in the following century. Behind its ablaq façade, its three main sections consisted of a four-iwan plan with around a central dome.[116]

During Timur's invasion in 1400 Aleppo surrendered without a fight and was spared the destruction dealt to Damascus. However, like the rest of Syria, its craftsmanship suffered from the mass deportation of the region's craftsmen to Timur's capital in Central Asia.[117] Nonetheless, in the 15th century the city continued to prosper, grew beyond its old walls, and new monumental buildings were added in various areas.[116] The al-Utrush Mosque, begun in 1399 by the Mamluk governor Aqbugha al-Utrush but finished by his successor Demirdash in 1410,[117] displayed a much stronger Mamluk influence in its details and was built on a more imposing scale.[116] One of the most audacious constructions was a large banquet hall or reception hall built on top of the two Ayyubid towers and gatehouse at the entrance of the Citadel. It was added by the Mamluk governor Jakam min 'Iwad in 1406–07. The hall has ornate windows on its outer façade, while the interior was covered by roof of nine domes. (The hall later fell into ruins and was reconstructed in the 20th century with a flat roof and limited accuracy.)[116][47][118] The oldest surviving khans in the city date from this period, including the Khan al-Qadi (1441), originally built as a madrasa but quickly converted to commercial use, and the Khan al-Sabun (1479), notable for its ornate window.[116]

- Mamluk architecture in Aleppo

The minaret of the Mehmendar Mosque (1302)

The minaret of the Mehmendar Mosque (1302) Maristan of Arghun al-Kamili (1354), entrance portal (possibly Ayyubid)

Maristan of Arghun al-Kamili (1354), entrance portal (possibly Ayyubid) Maristan of Arghun al-Kamili (1354), internal courtyard

Maristan of Arghun al-Kamili (1354), internal courtyard Muqarnas over the entrance of the Tawashi Mosque (1372)

Muqarnas over the entrance of the Tawashi Mosque (1372) Decorative engaged column carved at the Tawashi Mosque (1372)

Decorative engaged column carved at the Tawashi Mosque (1372) Hammam of Yalbugha (1389)

Hammam of Yalbugha (1389) The Mamluk banquet hall (1406–07) built over the Ayyubid gatehouse of the Citadel of Aleppo

The Mamluk banquet hall (1406–07) built over the Ayyubid gatehouse of the Citadel of Aleppo Details of the decorated façade of the al-Utrush Mosque (1410)

Details of the decorated façade of the al-Utrush Mosque (1410) Ornate window over the entrance of the Khan al-Sabun (1479)

Ornate window over the entrance of the Khan al-Sabun (1479) Mausoleum of Khayr Bak (1514) (not to be confused with the funerary complex by the same founder in Cairo)

Mausoleum of Khayr Bak (1514) (not to be confused with the funerary complex by the same founder in Cairo)

Jerusalem

Jerusalem was another site of significant patronage outside Cairo. The frequent building activity in the city during this period is evidenced by the 90 remaining buildings that date from the 13th to 15th centuries.[119] The types of structures built included madrasas, libraries, hospitals, caravanserais, fountains (or sabils), and hammams (bathhouses). The structures were built mostly in stone and often feature muqarnas and ablaq decoration.[119] While sultans themselves only occasionally built new monuments in the city, many more were built by local Mamluk amirs and even by private citizens. The sultans did, however, concern themselves with restoring and maintaining the Muslim holy sites in the city.[95][120] Al-Nasir Muhammad, for example, restored both the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque.[120]

Much of the building activity was concentrated around the edges of the Haram al-Sharif, typically clustering around the main streets leading to the sanctuary.[119][120] Old gates to the Haram al-Sharif lost importance and new gates were built,[119] while significant parts of the northern and western porticos (riwaqs) along the edge of the Haram were completed in this period.[121][120] Bab al-Qattanin (Cotton Gate), for example, was built in 1336–7 and became an important entrance to the compound from the city's commercial center, a new market called Suq al-Qattatin which was built at the same time.[119][121] The patron of this construction was Tankiz, the Mamluk amir in charge of Syria during al-Nasir Muhammad's reign. He also built the Tankiziyya Madrasa (1328–29) on the western edge of the Haram al-Sharif.[121] Other monuments from the Mamluk era in the city include the Madrasa as-Sallāmiyya (1338),[122] the al-Fakhriyya Minaret on the edge of the Haram al-Sharif (date unknown but built sometime between 1345 and 1496),[123] the Madrasa al-Manjakiyya (1361),[124] the Palace of Lady Tunshuk (circa 1388, but integrated into later buildings) and the Mausoleum of Lady Tunshuk across the street from it (built before 1398).[125] Sultan Qaytbay was a notable patron in the city, building the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya (only partly preserved) on the edge of the Haram al-Sharif, completed in 1482 and considered a major Mamluk monument in its own right, and the nearby Sabil of Qaytbay, built shortly after in 1482.[119][121] The Madrasa al-Muzhiriyya was also built in his reign, in 1480–81, by a Mamluk official.[126] Qaytbay's constructions were the last notable Mamluk buildings built in the city.[127]

- Mamluk architecture in Jerusalem

Portal of the Madrasa al-Tankiziyya (1328–29)

Portal of the Madrasa al-Tankiziyya (1328–29).jpg.webp) Suq al-Qattanin (Cotton Market), originally built by Tankiz (1336–7)

Suq al-Qattanin (Cotton Market), originally built by Tankiz (1336–7).jpg.webp) Bab al-Qattanin, a gate on the Haram al-Sharif from the market (1336–7)

Bab al-Qattanin, a gate on the Haram al-Sharif from the market (1336–7) Portal of the Madrasa as-Sallāmiyya (1338)

Portal of the Madrasa as-Sallāmiyya (1338) Al-Fakhriyya Minaret on the edge of the Haram al-Sharif, built in the second half of the 14th century or in the 15th century

Al-Fakhriyya Minaret on the edge of the Haram al-Sharif, built in the second half of the 14th century or in the 15th century Portico windows of the Madrasa al-Manjakiyya, built on top of other structures on the western edge of the Haram al-Sharif (1351)

Portico windows of the Madrasa al-Manjakiyya, built on top of other structures on the western edge of the Haram al-Sharif (1351).jpg.webp) Portal of the Palace of Lady Tunshuk (circa 1388)

Portal of the Palace of Lady Tunshuk (circa 1388) Street façade of the Madrasa al-Muzhiriyya (1480–81)

Street façade of the Madrasa al-Muzhiriyya (1480–81) Portal of the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya (1482)

Portal of the Madrasa al-Ashrafiyya (1482) Sabil of Qaytbay on the Haram al-Sharif (1482)

Sabil of Qaytbay on the Haram al-Sharif (1482)

Tripoli

The ancient city of Tripoli (present-day Lebanon) was captured by Sultan Qalawun from the Crusaders in 1289. The Mamluks destroyed the old city and built a new city 4 km inland from it.[128] About 35 monuments from the Mamluk city have survived to the present day, including mosques, madrasas, khanqahs, hammams, and caravanserais, many of them built by local Mamluk amirs.[129] Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil (r. 1290–93) founded the city's first congregational mosque, still known today as the Great Mosque of Tripoli,[128] in either late 1293 or 1294 (693 AH).[130][131] Six madrasas were built around the mosque: al-Khayriyya Hasan (circa 1309 or after), al-Qartawiyya (founded circa 1326), al-Shamsiyya (1349), al-Nasiriyya (1354–60), and al-Nuriyya (14th century), and an unidentified "Mashhad" Madrasa.[131][132][133][134][135][136][137] The Argun Shah Mosque, founded in 1350, was accompanied by the Madrasa al-Saqraqiyya (1356) and the Madrasa al-Khatuniyya (1373).[131] Other Mamluk madrasas in the city include the Madrasa al-Tawashiyya.[132] The al-Burtasiyya appears to have served as both a mosque and a madrasa.[131][138] Among the seven other mosques built in the Mamluk period, the Taynal Mosque (circa 1336) is notable for its unusual layout, consisting of two consecutive halls, with the second one containing the mihrab and accessed from the first one through an ornate portal with muqarnas, ablaq and geometric decoration.[131][139] The Mamluks did not fortify the city with walls but restored and reused a Crusader citadel on the site.[128] Seven watch towers were constructed near the sea to guard the city, including the surviving Lion Tower.[140]

- Mamluk architecture in Tripoli (Lebanon)

Great Mosque of Tripoli (circa 1294); the arcades are Mamluk but the minaret was an earlier Christian structure[130]

Great Mosque of Tripoli (circa 1294); the arcades are Mamluk but the minaret was an earlier Christian structure[130].jpg.webp) Street façade of the Madrasa al-Nasiriyya (1354–60)

Street façade of the Madrasa al-Nasiriyya (1354–60).jpg.webp) The entrance portal of the Madrasa al-Nuriyya (14th century)

The entrance portal of the Madrasa al-Nuriyya (14th century)_(7413148424).jpg.webp) Details of the portal of the Madrasa al-Tawashiyya

Details of the portal of the Madrasa al-Tawashiyya The inner portal of the Taynal Mosque (circa 1336)

The inner portal of the Taynal Mosque (circa 1336) The Lion Tower, a coastal watch tower built by the Mamluks near Tripoli (photo circa 1900)

The Lion Tower, a coastal watch tower built by the Mamluks near Tripoli (photo circa 1900)

Other towns in Egypt

Alexandria, the ancient capital of Egypt, declined over the Mamluk period. It did not receive significant patronage, but Mamluk rulers did build heavy fortifications to defend it from seaborne attacks.[141][34] The ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria, which was progressively damaged by earthquakes, was maintained up until its collapse in the first half of the 14th century.[34][142] The most notable Mamluk monument in the city is the Citadel of Qaytbay, built afterwards upon the ruins of the lighthouse. The construction of the citadel re-used the remaining foundations of the lighthouse and was completed in 1479.[141][142]

One of the oldest surviving mosques in Damietta is the Mosque of al-Mu'ini (mid-15th century), which is also described in historical sources as a madrasa. It includes the mausoleum of its founder, Muhammad al-Mu'ini, a rich merchant who died in 1455. The mosque has been much restored and its original octagonal minaret was demolished due to safety concerns in 1929. Its original Mamluk portal, no longer used as the main entrance, is located next close to the mausoleum chamber (whose dome is visible) and to original minaret. Its most remarkable feature is an elaborate marble mosaic pavement that scholar Bernard O'Kane believes is from the original Mamluk construction and which Doris Behrens-Abouseif describes as comparable to the best examples in Cairo.[143][144]

The town of al-Khanqah, north of Cairo, was formerly known as Siryaqus until Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad built a khanqah, palace, and marketplace there in 1324. However, the only surviving Mamluk structure is the Mosque of Sultan al-Ashraf Barsbay, dating to 1437. It consists of a hypostyle hall with a central courtyard. Many of the columns are reused from old structures. The mosque is sparsely decorated except for the mihrab, which has marble inlaid with geometric and arabesque motifs. The ceiling was originally had painted decoration as well, but only a part of this was restored in the 20th century and remains today. The minaret is almost identical to the minaret of Barsbay's mosque at al-Muizz Street in Cairo, built 12 years earlier.[145]

The Mosque of Asalbay, in the Fayoum, dates from 1498 to 1499 but has been significantly modified and restored over time. Among its original elements is a well-preserved and restored wooden minbar decorated with geometric patterns and inlay.[146]

References

Citations

- Williams 2018.

- Raymond 1993.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 70, 85–87, 92–93.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 70.

- Williams 2018, p. 17.

- Sanders, Paula (2008). Creating Medieval Cairo: Empire, Religion, and Architectural Preservation in Nineteenth-century Egypt. American University in Cairo Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 9789774160950.

- Avcıoğlu, Nebahat; Volait, Mercedes (2017). ""Jeux de miroir": Architecture of Istanbul and Cairo from Empire to Modernism". In Necipoğlu, Gülru; Barry Flood, Finbarr (eds.). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 1140–1142. ISBN 9781119068570.

- Williams 2018, p. 30-33.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture; VI. c. 1250–c. 1500; C. Central Islamic lands". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Raymond 2000, p. 122

- Raymond 2000, pp. 120–28

- Ruggles, D.F. (2020). Tree of pearls: The extraordinary architectural patronage of the 13th-century Egyptian slave-queen Shajar al-Durr. Oxford University Press.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 114.

- Williams 2018, p. 30-31.

- Raymond 1993, p. 122.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 132-141.

- Raymond 1993, p. 122-124, 140-142.

- Raymond 1993, p. 124-140.

- Raymond 1993, p. 143-153.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 201-213.

- Williams 2018, p. 78-84.

- Raymond 1993, p. 78.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 82.

- Williams 2018, p. 78.

- Williams 2018, p. 227.

- Raymond 1993, p. 169-177.

- Clot, André (1996). L'Égypte des Mamelouks: L'empire des esclaves, 1250–1517. Perrin.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 228-229.

- Williams 2018, p. 281.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 232.

- Williams 2018, p. 31-33.

- Williams 2018, p. 33-34.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 69.

- Blair & Bloom 2009, p. 152.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 92-93.

- Williams 2018, p. 286-287.

- Williams 2018, p. 34.

- Denoix, Sylvie; Depaule, Jean-Charles; Tuchscherer, Michel, eds. (1999). Le Khan al-Khalili et ses environs: Un centre commercial et artisanal au Caire du XIIIe au XXe siècle. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard.

- Williams 2018, p. 230.

- Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 161.

- Bloom & Blair 1995, p. 251.

- Rabbat, Nasser. "Ottoman Architecture in Cairo: The Age of the Governors". web.mit.edu. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Neo-Mamluk Style Beyond Egypt". Rawi Magazine. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- Williams 2018, p. 172-173.

- Bloom & Blair 2009, Aleppo

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 71.

- Williams 2018, p. 108.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 76-77.

- Williams 2018, p. 31.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 73-77.

- Williams 2018, p. 30.

- Williams 2018, p. 109.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 90.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Ablaq". Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 9781134613663.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 77.

- Williams 2018, p. 225-226.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 153-155.

- Williams 2018, p. 30-31, 38-39, and more.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 93-94.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 94.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 95-97.

- Williams 2018, p. 126.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 77-80.

- Williams 2018, p. 57.

- Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 17.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 135.

- Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 20-22.

- Williams 2018, p. 114.

- Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 26.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 206.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 206, 298.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 77.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 80-84.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 83.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 83–84.

- Williams 2018, p. 283.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 234.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 87.

- Williams 2018, p. 34, 288.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 90.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 86.

- Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 16.

- Burns 2007, p. 210.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 207-209.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 86, 198, 219.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 241.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 89.

- Williams 2018, p. 90.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, p. 94.

- Sayed, Hazem I. (1987). The Rab' in Cairo: A Window on Mamluk Architecture and Urbanism (PhD thesis). MIT. pp. 7–9, 58. hdl:1721.1/75720.

- Raymond 2000, p. 123, 157.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 65-70.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 66.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 92–93.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 66-68.

- Kenney, Ellen (2012). "A Mamluk Monument Reconstructed: an Architectural History of the Mosque and Mausoleum of Tankiz al-Nasiri in Damascus". In Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (ed.). The Arts of the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria: Evolution and Impact. V&R unipress; Bonn University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-3-89971-915-4.

- Burns 2007, p. 209.

- Burns 2007, p. 197.

- Burns 2007, p. 205-206.

- Burns 2007, p. 199.

- Rabbat, Nasser (2010). Mamluk History through Architecture: Monuments, Culture and Politics in Medieval Egypt and Syria. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78673-386-3.

- Burns 2007, p. 211-212.

- Burns 2007, p. 213.

- Burns 2007, p. 209-210.

- Burns 2007, p. 210-211.

- Burns 2007, p. 211.

- Burns 2007, p. 214.

- Burns 2007, p. 208.

- Burns 2007, p. 220-221.

- Daiber, Verena. "Madrasa al-Jaqmaqiyya". Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers. Retrieved 2022-02-04.

- Burns, Ross (2009) [First edition in 1992]. The Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845119478.

- Burns 2007, p. 220.

- Burns 2007, p. 221.

- Burns, Ross (2017). Aleppo: A history. Routledge. pp. 179–198. ISBN 9780815367987.

- Blair & Bloom 1995, pp. 85.

- Gonnella, Julia (2012). "Inside Out: The Mamluk Throne Hall in Aleppo". In Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (ed.). The Arts of the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria: Evolution and Impact. Bonn University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9783899719154.

- Bloom & Blair 2009, "Jerusalem"

- Little, Donald P. (2000). "Jerusalem under the Ayyubids and Mamluks 1187–1516 AD". In Asali, K. J. (ed.). Jerusalem in History. Olive Branch Press. pp. 177–200. ISBN 9781566563048.

- Burgoyne 1987.

- "Madrasa al-Salamiyya". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- Burgoyne 1987, p. 270.

- Burgoyne 1987, p. 384.

- Burgoyne 1987, p. 485, 505.

- Burgoyne 1987, p. 579.

- Burgoyne 1987, p. 589-612.

- Luz, Nimrod (2002). "Tripoli Reinvented: A Case of Mamluk Urbanization". In Lev, Yaacov (ed.). Towns and material culture in the medieval Middle East. Brill. pp. 53–71. ISBN 9004125434.

- Bloom & Blair 2009, Tripoli (i)

- "Jami' al-Mansuri al-Kabir". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- Mahamid, Hatim (2009). "Mosques as higher educational institutions in Mamluk Syria". Journal of Islamic Studies. 20 (2): 188–212. doi:10.1093/jis/etp002.

- Mohamad, Danah (2020). Review of the Development and Change of Tripoli Bazaar in Lebanon (PDF). Bursa Uludağ University (Master's thesis). p. 81.

- "Qantara - Madrasa al-Qartâwîyya". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Madrasa al-Nasiriyya". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Madrasa Khayriyya Hasan". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Madrasa al-Nuriyya". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Anonymous Mashhad". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Al-Burtasiya mosque-madrasa". qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Qantara - Mosquée Taynâl". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- "Lion Tower". qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- Frenkel, Yehoshua (2014). "Alexandria in the Ninth/Fifteenth Century: A Mediterranean Port City and a Mamluk Prison City". Al-Masaq. 26 (1): 78–92. doi:10.1080/09503110.2014.877198. S2CID 154903868.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2006). "The Islamic History of the Lighthouse of Alexandria". Muqarnas. 23 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000093.

- O'Kane 2016, p. 196-197.

- Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 68.

- O'Kane 2016, p. 186-191.

- O'Kane 2016, p. 226-229.

Sources

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). Islamic architecture in Cairo : an introduction. Leiden et al.: Brill. pp. 161-162. ISBN 9004086773.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2007). Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774160776.

- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06465-0.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- Burgoyne, Michael Hamilton (1987). Mamluk Jerusalem: An Architectural Study. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem by World of Islam Festival Trust. ISBN 9780905035338.

- Burns, Ross (2009) [First edition in 1992]. The Monuments of Syria: A Guide. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845119478.

- Burns, Ross (2007). Damascus: A History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-48850-6.

- Burns, Ross (2017). Aleppo: A history. Routledge. pp. 179–198. ISBN 9780815367987.

- O'Kane, Bernard (2016). The Mosques of Egypt. American University of Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774167324.

- Raymond, André (1993). Le Caire (in French). Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-02983-2. English translation: Raymond, André (2000). Cairo. Translated by Wood, Willard. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00316-3.

- Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9774168550.

.jpg.webp)