Stucco decoration in Islamic architecture

Stucco decoration in Islamic architecture refers to carved or molded stucco and plaster. The terms "stucco" and "plaster" are used almost interchangeably in this context to denote most types of stucco or plaster decoration with slightly varying compositions.[1] This decoration was mainly used to cover walls and surfaces and the main motifs were those predominant in Islamic art: geometric, arabesque (or vegetal), and calligraphic, as well as three-dimensional muqarnas.[2][3][4] Plaster of gypsum composition was extremely important in Islamic architectural decoration as the relatively dry climate throughout much of the Islamic world made it easy to use this cheap and versatile material in a variety of spaces.[4]

Stucco decoration was already used in ancient times in the region of Iran and the Greco-Roman Mediterranean.[5] In Islamic architecture, stucco decoration appeared during the Umayyad period (late 7th–8th centuries) and underwent further innovations and generalization during the 9th century under the Abbasids in Iraq, at which point it spread further across the Islamic world and was incorporated into regional architectural styles.[2][6] Examples of historic carved stucco decoration are found in Egypt, Iran, Afghanistan, and India, among other areas.[7][4] It was commonly used in "Moorish" or western Islamic architecture in the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and parts of North Africa (the Maghreb), since at least the Taifa and Almoravid periods (11th–12th centuries).[2] In the Iberian Peninsula it reached a creative pinnacle in Moorish architecture during the Nasrid dynasty (1238–1492), who built the Alhambra.[8] Mudejar architecture also made broad use of such decoration.[9][10] The Spanish term yesería is sometimes used in the context of Islamic and Mudéjar architecture in Spain.[9][11]

History

Origins and early development

The use of carved stucco has been documented back to ancient times. Stucco decoration was used in Iran, Central Asia and the Greco-Roman Mediterranean,[5] though it was most strongly associated with Iranian architecture under the Parthians and Sasanians.[6] As the Islamic conquests of the 7th century captured Mesopotamia, Iran, and Central Asia and annexed them to the new Islamic empire, the long tradition of carved and painted stucco decoration in these regions was assimilated into early Islamic architecture.[4] The Umayyad caliphs (661–750 AD) made use of carved stucco in their architecture,[5] although it was of limited scope until the late Umayyad period.[12] Examples of early 8th century stucco survive at Umayyad sites like Khirbat al-Mafjar and Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (whose portal is now at National Museum of Damascus).[12][2] As with other early Islamic sculptural decoration, the carved stucco decoration in the Umayyad period started out with an eclectic mix of styles originating in existing Classical, early Byzantine, and ancient Near Eastern artistic traditions.[2][4]

It was only in the 9th century that a distinctively "Islamic" style of stucco decoration emerged.[4] Under the Abbasids, based in Iraq, stucco decoration developed more abstract motifs, as seen in the 9th-century palaces of Samarra. Three styles are distinguished by modern scholars: "style A" consists of vegetal motifs, including vine leaves, derived from more traditional Byzantine and Levantine styles; "style B" is a more abstract and stylized version of these motifs; and "style C", also known as the "beveled" style, is entirely abstract, consisting of repeating symmetrical forms of curved lines ending in spirals.[2][4][7]: 267–268 The Abbasid style became popular throughout the lands of the Abbasid Caliphate and is found as far as Afghanistan (e.g. Mosque of Haji Piyada in Balkh) and Egypt (e.g. Ibn Tulun Mosque).[2][4][7]: 1

Regionalization

As the Abbasid realm fragmented in the following centuries, architectural styles became increasingly regionalized.[2] Towards the 11th century, muqarnas, a technique of three-dimensional geometric sculpting often compared to "stalactites", is attested across many parts of the Islamic world, often carved from stucco. It grew more popular from the 12th century onward.[13]

Eastern Islamic lands

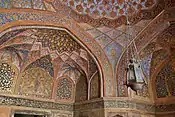

In the Greater Iranian region, a fairly distinctive style evolved from Abbasid models, employing stucco carved in high relief, especially in the decoration of mihrabs during the periods of Seljuk and Mongol domination.[2][7]: 121–122 Among the most notable examples are the mihrab of Friday Mosque of Ardistan (c. 1135 or 1160),[2] the Ilkhanid mihrab at the Great Mosque of Isfahan (1310),[14] and the mihrab of the Pir i-Bakran Mausoleum (early 14th century).[2] An earlier Mesopotamian tradition of muqarnas domes, as seen in the Imam ad-Dur Shrine near Samarra (1085–1090), was also passed on to Iran, with an important early example being the Tomb of 'Abd al-Samad at Natanz (1307–1308).[4] The Iranian fashion of stucco decoration spread to other nearby regions. In Indo-Islamic architecture (in the Indian subcontinent) it was commonly either sculpted or used to apply painted decoration, or both, although its importance declined in the mid-16th century. In the Deccan, stucco was often used to create round architectural medallions with plant motifs.[4] In Iran itself, high relief stucco carving grew less popular during the 15th century but then underwent a revival at the beginning of the 17th century, under the Safavids, when it was used in palace architecture.[4]

Egypt

Fine stucco carving was still employed in Egypt during the Fatimid period (10th to 12th centuries). The earlier Samarra styles evolved to incorporate more naturalistic forms. In carved Arabic inscriptions, for example, flowers and leaves were added to embellish the letters. One of the finest examples from this period is the mihrab of the al-Juyushi Mosque.[4][2] After this period, stucco decoration became less important and only occasional examples are attested under Mamluk rule, most of it in Cairo.[2][4] While it was common enough under the Bahri Mamluks (13th to 14th centuries), it was largely supplanted by other forms of decoration afterwards.[15]: 90 The existing stucco examples from this period are nonetheless of high quality, as seen in the mihrab of the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, dated to 1304.[2][4] This monument also appears to demonstrate the influence or presence of craftsmen from other regions. The style of stucco decoration around the mihrab, for example, is reminiscent of Iranian stucco work in the style of Tabriz under the contemporary Ilkhanids.[15]: 154–155 [16]: 226 The lavish stucco decoration of the madrasa's minaret, on the other hand, appears to involve contemporary Maghrebi styles and craftsmanship alongside local motifs.[16]: 225 [17]: 77 Stucco decoration underwent a brief revival during the reign of Qaytbay (r. 1468–1496), when it was used again in interior decoration.[15]: 90

Western Islamic lands

The Umayyad conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the 8th century brought Islam to this region, which subsequently became known as Al-Andalus in Arabic. The establishment of a new Umayyad dynasty in Córdoba after 756, in the form of the Emirate of Córdoba (and the Caliphate of Córdoba after 929), led to the development of a distinctive style of Islamic architecture culminating in architectural masterpieces such as the Great Mosque of Córdoba. This style, popularly known as "Moorish" architecture,[18] was also influenced by other Islamic architectural traditions further east.[19] Archeological evidence near Kairouan in Tunisia and Sedrata in Algeria indicate that the Abbasid style of carved stucco was also introduced to the region of Ifriqiya.[4] Initially, however, the Abbasid style had little influence on art in al-Andalus, where stucco began to be used for decoration in the later half of the 10th century.[4]

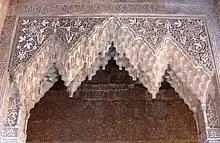

The western Islamic architectural tradition continued to evolve over the subsequent Taifas period (11th century) and under the rule of North African empires, the Almoravids and the Almohads (11th to 13th centuries).[20][21] Stucco became the most common medium of decoration in the 11th century.[4] It was carved in high relief during the Taifas period (e.g. Aljafería Palace in Zaragoza) and during the Almoravid period (e.g. Qubba al-Barudiyyin in Marrakesh).[2] The elaborate decorative style of the Almoravids was initially restrained under their successors, the Almohads, whose monuments attest to a more subdued but elegant decoration. After them, however, architectural decoration reached new heights of lavishness in Al-Andalus and the western Maghreb.[4] The fashion evolved to favour stucco carved in shallow relief and to cover large surfaces along upper walls and under vaults.[2] Starting in the 13th century, the Nasrid dynasty in Granada constructed the palace complex known today as the Alhambra, which is replete with rich stucco decoration. Stucco decoration was also used profusely in the monuments of the Marinid dynasty in North Africa, particularly in madrasas, a number of which have survived in Morocco.[21]: 188 The al-'Attarin Madrasa in Fez, for example, built by the Marinids between 1323 and 1325, is one of the finest examples of this decoration.[4] Comparable stucco decoration has also been found in the former palace of the Zayyanids in Tlemcen, Algeria.[22]: 267

Mudéjar decoration in Christian Spain

As Christian kingdoms progressively conquered the Iberian Peninsula, they continued to use the Islamic style, or "Mudéjar" style, in many of their new buildings. Moorish or Islamic-style plasterwork is found, for example, in 14th-century Castilian architecture such as the palace of Pedro I in the Alcázar of Seville, the Royal Convent of Santa Clara in Tordesillas (former palace of Alfonso XI), and the Jewish Synagogue of El Tránsito in Toledo. In these examples, Christian inscriptions and Castilian heraldry are also included against backgrounds of traditional Islamic arabesque and geometric motifs.[9] An important tradition of decorative plasterwork grew in Toledo, which fell to Castilian control in 1085. Many examples of Mudéjar plasterwork throughout Castile can be attributed to craftsmen from this city. From the 11th century to the mid-14th century, such plasterwork continued to be dominated by motifs of Islamic origin that are similar to contemporary Almoravid, Almohad, or Nasrid art. After the mid-14th century, other motifs were added to this repertoire, such as vine and oak leaves inspired by Gothic art and, later, figures of people and animals.[23]

Motifs and styles

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Islamic and Mujédar stucco decoration followed the main types of ornamentation in Islamic art: geometric, arabesque or vegetal, and calligraphic motifs.[3][2] Three-dimensional muqarnas was often also carved in stucco,[24][7] most typically found as transitional elements on vaults, domes, capitals, friezes, and doorways.[7]: 206–208 This motif consisted of interlocking niches projected in many levels one over the other, forming geometric patterns when seen from below.[7]: 206–208 [13] Walls were covered with the remaining ornamental types, intermixed and arranged for visual appeal and impact.[25]: 81 Stucco was sometimes used for murals and painted decoration in some regions and periods,[24] a technique that was popular in Iran for example.[26] Figural motifs (such as animals or human forms) are also attested in stucco carving, though they were not in general usage across the Islamic world.[2]

Initially, elaborately carved three-dimensional decoration was found in some palaces during the Umayyad period, while during the Abbasid period the carving became shallower and more flattened.[2] High relief stucco sculpting was still notably employed later to decorate the mihrabs of mosques in medieval Iran, using arabesques of stems and leaves on multiple levels carved in depth.[2][3] Ornate window grilles in Islamic architecture were also commonly carved from stucco and filled with stained glass.[4][27] More exceptionally, some mosques in Morocco and Algeria contained decorative domes made of stucco with intricately carved arabesques that were pierced to allow light to pass through, as in the Great Mosque of Tlemcen (built and decorated under the Almoravids in the early 12th century).[24][21] In Nasrid and Mudéjar architecture, the lower section or dado section of walls was typically covered in mosaic tile (zellij), whereas carved stucco covered the remaining wall above the dado with arabesques, geometric patterns, and epigraphic motifs. A similar configuration predominated in Marinid architecture.[28][21]: 188 [24]

- Examples of motifs and styles

.jpg.webp) Star-like polygonal geometric motif (with arabesque details) in stucco wall decoration at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid)

Star-like polygonal geometric motif (with arabesque details) in stucco wall decoration at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid) Arabesque (vegetal) motifs in carved stucco on the mihrab of the Friday Mosque of Ardistan, Iran (12th century, Seljuk)

Arabesque (vegetal) motifs in carved stucco on the mihrab of the Friday Mosque of Ardistan, Iran (12th century, Seljuk).jpg.webp) Calligraphic frieze in carved stucco at the Al-'Attarin Madrasa in Fez (14th century, Marinid)

Calligraphic frieze in carved stucco at the Al-'Attarin Madrasa in Fez (14th century, Marinid) Stucco "Stalactite"-style muqarnas in the Palace of the Lions at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid)

Stucco "Stalactite"-style muqarnas in the Palace of the Lions at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid).jpg.webp) Full muqarnas dome in stucco in the Palace of the Lions at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid)

Full muqarnas dome in stucco in the Palace of the Lions at the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid)_7749.jpg.webp) Stucco-decorated gate of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (early 8th century, Umayyad), reconstructed at the National Museum of Damascus

Stucco-decorated gate of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi (early 8th century, Umayyad), reconstructed at the National Museum of Damascus.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) Stucco grille window from the al-Salih Tala'i Mosque in Cairo (12th century, Fatimid), with arabesque and Kufic Arabic motifs

Stucco grille window from the al-Salih Tala'i Mosque in Cairo (12th century, Fatimid), with arabesque and Kufic Arabic motifs Stucco wall decoration and stucco grille windows in the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fez (14th century, Marinid)

Stucco wall decoration and stucco grille windows in the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fez (14th century, Marinid).jpg.webp) Sebka, arabesque, and epigraphic motifs on the walls of the Hall of Ambassadors in the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid)

Sebka, arabesque, and epigraphic motifs on the walls of the Hall of Ambassadors in the Alhambra (14th century, Nasrid) Painted and carved plaster decoration inside Akbar's Tomb in Agra, India (early 17th century, Mughal)

Painted and carved plaster decoration inside Akbar's Tomb in Agra, India (early 17th century, Mughal)

Material

In the context of Islamic architecture, the terms "stucco" and "plaster" are used almost interchangeably to denote most types of stucco or plaster decoration with varying compositions. In its most flexible usage, it can even denote a material made from a mixture of mud and clay.[1] In more precise terms, however, "stucco" is a substance based on lime which is harder and sets more slowly, while "plaster" is a substance based on gypsum which is softer and sets more quickly.[1] The mixture could consist of pure gypsum and dissolved glue or of lime mixed with powdered marble or eggshell.[4]

In art history, the Spanish term yesería is most often associated with carved stucco or plaster on the Iberian peninsula and Latin America. In historic Nasrid architecture, the composition and color of stucco varied depending upon the purity of gypsum stone and additives used to bestow properties to the mixtures such as hardness, setting time, and binding.[25]: 23, 56 The chemical formula for gypsum is CaSO4•2H2O. Gypsum is the most common sulfate mineral.[29] The combination of abundant source material, ease of preparation and handling, wide adaptability for use, and quick setting time accounted for stucco's widespread use.[25] In the 19th century, plaster of Paris was used in restoration and redecoration at later dates over the original stucco layer.[25]: 23

Technique

Throughout the Islamic world, stucco was smoothed and the decorative designs were marked out with a pointed instrument. The carving was then done with iron tools while the material was still slightly wet. Evidence of this technique has been found in unfinished stucco decoration at Khirbat al-Mafjar (8th century) near Jericho and in the interior of the Kutubiyya Mosque's minaret in Marrakesh (12th century).[4] Alternatively, the stucco could be cast from molds.[4] In Iran, gypsum mixtures were initially stirred continuously until they lost their ability to set rapidly, and then this mixture was applied in several coats, taking up to 48 hours before setting.[4]

Nasrid stucco

In Nasrid art, the two basic techniques for creating stucco decoration were carving in situ and casting molds which were then attached to the structure. In situ carving was the most common method initially, but towards the early 14th century, during the reign of Muhammad III, molding became more standard.[8] Hand carving was accomplished by initially tracing design onto applied stucco layer and then carving using simple hand tools[8] of iron.[30] Casting allowed for more elaborate and intricate designs that could be repeated, creating systematic stylization.[8] Molds were commonly made from wood or plaster; the item was often cast in clay, then coated in gesso.[30] After molded pieces were attached to the walls, they were painted or whitewashed as needed.[8] Analysis of the original stuccos in the Alhambra show that Nasrid artisans were well versed in the properties of stucco and used different gypsum mixtures for carving and casting. For example, additives to slow drying and setting were used on stucco mixtures that were carved in place to allow artisans more time to complete their work.[25]: 23 [8]

Stucco was often polychromed. Age and weather, along with centuries of redecoration and restoration have significantly altered the original appearance of most stucco that date to the Nasrid period.[31] Current advances in analytical instrumentation that allows for in situ analysis of the stucco are yielding information about original pigments and techniques.[32] A further example of Nasrid artisans skill with stucco was their use of high purity gypsum coating that served both as a sealant and a preparatory stage for subsequent painting or gilding on the original stucco layer. The Alhambra has been the focus of recent investigations. The primary colors used on the stucco of the Alhambra were red, blue, green, golden, and black. Spectroscopic analysis of pigments attributed to original decoration of the Alhambra show cinnabar as the pigment used for red color. Lapis lazuli, a highly prized and expensive pigment, accounts for the blue. Malachite has been detected as the source of the green hues. Carbon black was used for black pigment.[33] Gilding, especially on the muqarnas, has been noted. The application of both pigment and gilding to these geometrically complex ceilings showed their knowledge and skill in optical allusion and spatial harmony. Investigations have focused on the muqarnas ornamented ceiling in the Hall of Kings in the Alhambra. Data is revealing the expansive use of two of the most expensive materials on this ceiling, lapis lazuli and gold leaf revealing the original dazzling opulence of the space.[34]

See also

- Pargetting for another tradition of decorative plasterwork

- Tadelakt

- Qadad

References

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Stucco and plasterwork". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780195309911.

General terms for a decorative art that, at its simplest, is a render of mortar designed to decorate a smooth wall or ceiling and, in its more sophisticated form, is a combination of high-relief, sculptural and surface decoration. The words stucco and plaster are used virtually interchangeably and, most flexibly, can be applied to mixtures of mud or clay; more precisely, however, stucco usually means a hard, slow-setting substance based on lime as opposed to quick-setting plaster based on gypsum.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture; X. Decoration; A. Sculpture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 193–198. ISBN 9780195309911.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Ornament and pattern". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–78. ISBN 9780195309911.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Stucco and plasterwork". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. pp. 235–238. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Hamilton, R. W. (1953). "Carved Plaster in Umayyad Architecture". Iraq. 15 (1): 43–55. doi:10.2307/4199565. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4199565. S2CID 192962299.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). "stucco". Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. pp. 267–268. ISBN 9781134613663.

- Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. ISBN 9781134613663.

- Victoria and Albert Museum, Online Museum (2012-02-02). "Nasrid Plasterwork: Symbolism, Materials & Techniques". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- Nickson, Tom (2009). "The Locked-Up Garden: The Nature of Medieval Castile". In Cleaver, Laura; Gerry, Kathryn B.; Harris, Jim (eds.). Art & Nature: Studies in Medieval Art and Architecture. Courtauld Institute of Art. pp. 44–51. ISBN 978-1-907485-00-8.

- Borrás Gualís, Gonzalo M.; Lavado Paradinas, Pedro; Pleguezuelo Hernández, Alfonso; Pérez Higuera, María Teresa; Mogollón Cano-Cortés, María Pilar; Morales, Alfredo J.; López Guzman, Rafael; Sorroche Cuerva, Miguel Ángel; Stuyck Fernández Arche, Sandra (2018). Mudéjar Art. Islamic Aesthetics in Christian Art. Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF (Museum Ohne Grenzen). ISBN 978-3-902782-15-1.

- Boloix-Gallardo, Bárbara, ed. (2021). A Companion to Islamic Granada. Brill. p. 458. ISBN 978-90-04-42581-1.

- Talgam, Rina (2004). The Stylistic Origins of Umayyad Sculpture and Architectural Decoration. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-447-04738-8.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Muqarnas". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Blair, Sheila; Bloom, Jonathan (2011). "The Friday Mosque at Isfahan". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. pp. 368–369. ISBN 9783848003808.

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (2007). Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774160776.

- Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan M. (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300064650.

- Barrucand, Marianne; Bednorz, Achim (1992). Moorish architecture in Andalusia. Taschen. ISBN 3822896322.

- Department of Islamic Art (2001). "The Art of the Umayyad Period in Spain (711–1031)". www.metmuseum.org. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2022-10-15.

- Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- Charpentier, Agnès; Terrasse, Michel; Bachir, Redouane; Amara, Ayed Ben (2019). "Palais du Meshouar (Tlemcen, Algérie) : couleurs des zellijs et tracés de décors du xive siècle". ArcheoSciences (in French). 432 (2): 265–274. doi:10.4000/archeosciences.6947. ISSN 1960-1360. S2CID 242181689.

- Borrás Gualís, Gonzalo M.; Lavado Paradinas, Pedro; Pleguezuelo Hernández, Alfonso; Pérez Higuera, María Teresa; Mogollón Cano-Cortés, María Pilar; Morales, Alfredo J.; López Guzman, Rafael; Sorroche Cuerva, Miguel Ángel; Stuyck Fernández Arche, Sandra (2018). "Itinerary IX; Mudéjar Plasterwork in Toledo". Mudéjar Art. Islamic Aesthetics in Christian Art. Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF (Museum Ohne Grenzen). ISBN 978-3-902782-15-1.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Bush, Olga (2018). Reframing the Alhambra. Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474416504.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4744-1650-4.

- Komaroff, Linda; Carboni, Stefano, eds. (2002). The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-58839-071-4.

- Keller, Sarah (2021). "Illuminating Transennae – A Technical Reinterpretation". In Giese, Francine (ed.). Mudejarismo and Moorish Revival in Europe: Cultural Negotiations and Artistic Translations in the Middle Ages and 19th-century Historicism. Brill. p. 514. ISBN 978-90-04-44858-2.

- Campbell, Gordon, ed. (2006). The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts: Two-volume Set. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-518948-3.

- "Gypsum Mineral | Uses and Properties". geology.com. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- "A lapidarium of yeserías". www.factumfoundation.org. Factum Foundation.

- Bush, Olga (2018). "Colour, Design and Medieval Optics". Reframing the Alhambra. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 17–58. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474416504.001.0001. ISBN 978-1-4744-1650-4.

- Dominguez-Vidal, A.; de la Torre-López, M. J.; Campos-Suñol, M. J.; Rubio-Domene, R.; Ayora-Cañada, M. J. (2014-01-22). "Decorated plasterwork in the Alhambra investigated by Raman spectroscopy: comparative field and laboratory study". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 45 (11–12): 1006–1012. Bibcode:2014JRSp...45.1006D. doi:10.1002/jrs.4439. ISSN 0377-0486.

- Dominguez-Vidal, Ana; Jose de la Torre-Lopez, Maria; Rubio-Domene, Ramon; Ayora-Cañada, Maria Jose (2012). "In situ noninvasive Raman microspectroscopic investigation of polychrome plasterworks in the Alhambra". The Analyst. 137 (24): 5763–5769. Bibcode:2012Ana...137.5763D. doi:10.1039/c2an36027f. ISSN 0003-2654. PMID 23085888.

- de la Torre-López, Maria Jose; Dominguez-Vidal, Ana; Campos-Suñol, Maria Jose; Rubio-Domene, Ramon; Schade, Ulrich; Ayora-Cañada, Maria Jose (2014-02-24). "Gold in the Alhambra: study of materials, technologies, and decay processes on decorative gilded plasterwork". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 45 (11–12): 1052–1058. Bibcode:2014JRSp...45.1052D. doi:10.1002/jrs.4454. ISSN 0377-0486.

External links

- Nasrid Plasterwork: Symbolism, Materials & Techniques (info on 'naqch hadîda' technique)

.jpeg.webp)