Damascus

Damascus (/dəˈmæskəs/ də-MASK-əs, UK also /dəˈmɑːskəs/ də-MAH-skəs; Arabic: دِمَشق, romanized: Dimašq, IPA: [diˈmaʃq]; Hebrew: דִמַשְׁק, romanized: Dimashq; Classical Syriac: ܕܰܪܡܣܘܩ, romanized: Darmsûq) is the capital of Syria, the oldest capital in the world according to some.[8][9][10] Known colloquially in Syria as aš-Šām (الشَّام) and dubbed, poetically, the "City of Jasmine" (مَدِيْنَةُ الْيَاسْمِينِ Madīnat al-Yāsmīn),[1] Damascus is a major cultural center of the Levant and the Arab world.

Damascus

دِمَشق | |

|---|---|

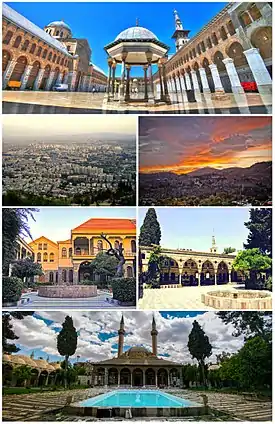

Umayyad Mosque General view of Damascus • Mount Qasioun Maktab Anbar • Azm Palace Sulaymaniyya Takiyya | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nicknames: | |

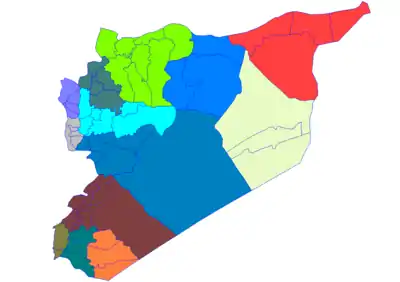

Damascus Location of Damascus within Syria  Damascus Damascus (Eastern Mediterranean)  Damascus Damascus (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 33°30′47″N 36°17′31″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Damascus Governorate, Capital City |

| Municipalities | 16 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Mohammad Tariq Kreishati[4] |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 105 km2 (41 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 77 km2 (29.73 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 680 m (2,230 ft) |

| Population (2022 estimate) | |

| • Capital city | 2,503,000[6] |

| Demonyms | English: Damascene Arabic: دِمَشقِيّ, romanized: Dımaşkî |

| Time zone | UTC+3 |

| Area code(s) | Country code: 963, City code: 11 |

| Geocode | C1001 |

| ISO 3166 code | SY-DI |

| Climate | BWk |

| HDI (2021) | 0.612[7] – medium |

| International airport | Damascus International Airport |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Ancient City of Damascus |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 20 |

| Region | Arab States |

Situated in southwestern Syria, Damascus is the center of a large metropolitan area. Nestled among the eastern foothills of the Anti-Lebanon mountain range 80 kilometres (50 mi) inland from the eastern shore of the Mediterranean on a plateau 680 metres (2,230 ft) above sea level, Damascus experiences an arid climate because of the rain shadow effect. The Barada River flows through Damascus.

Damascus is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.[11] First settled in the 3rd millennium BC, it was chosen as the capital of the Umayyad Caliphate from 661 to 750. After the victory of the Abbasid dynasty, the seat of Islamic power was moved to Baghdad. Damascus saw its importance decline throughout the Abbasid era, only to regain significant importance in the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods. Today, it is the seat of the central government of Syria. As of September 2019, eight years into the Syrian civil war, Damascus was named the least livable city out of 140 global cities in the Global Liveability Ranking.[12] As of June 2023, it was the least livable out of 173 global cities in the same Global Liveability Ranking.

Names and etymology

| ṯmsqw[13] in hieroglyphs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Era: New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) | |||||||||||

The name of Damascus first appeared in the geographical list of Thutmose III as ṯmśq (𓍘𓄟𓊃𓈎𓅱) in the 15th century BC.[14] The etymology of the ancient name ṯmśq is uncertain. It is attested as Imerišú (𒀲𒋙) in Akkadian, ṯmśq (𓍘𓄟𓊃𓈎𓅱) in Egyptian, Damašq (𐡃𐡌𐡔𐡒) in Old Aramaic and Dammeśeq (דַּמֶּשֶׂק) in Biblical Hebrew. A number of Akkadian spellings are found in the Amarna letters, from the 14th century BC: Dimašqa (𒁲𒈦𒋡), Dimašqì (𒁲𒈦𒀸𒄀), and Dimašqa (𒁲𒈦𒀸𒋡).

Later Aramaic spellings of the name often include an intrusive resh (letter r), perhaps influenced by the root dr, meaning "dwelling". Thus, the English and Latin name of the city is Damascus, which was imported from Greek Δαμασκός and originated from the Qumranic Darmeśeq (דרמשק), and Darmsûq (ܕܪܡܣܘܩ) in Syriac,[15][16] meaning "a well-watered land".[17]

In Arabic, the city is called Dimashq (دمشق Dimašq).[18] The city is also known as aš-Šām by the citizens of Damascus, of Syria and other Arab neighbors and Turkey (eş-Şam). Aš-Šām is an Arabic term for "Levant" and for "Syria"; the latter, and particularly the historical region of Syria, is called Bilād aš-Šām (بلاد الشام, lit. 'land of the Levant').[note 2] The latter term etymologically means "land of the left-hand side" or "the north", as someone in the Hijaz facing east, oriented to the sunrise, will find the north to the left. This is contrasted with the name of Yemen (اَلْيَمَن al-Yaman), correspondingly meaning "the right-hand side" or "the south". The variation ش ء م (š-ʾ-m'), of the more typical ش م ل (š-m-l), is also attested in Old South Arabian, 𐩦𐩱𐩣 (šʾm), with the same semantic development.[23][24]

Geography

Damascus was built in a strategic site on a plateau 680 m (2,230 ft) above sea level and about 80 km (50 mi) inland from the Mediterranean, sheltered by the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, supplied with water by the Barada River, and at a crossroads between trade routes: the north–south route connecting Egypt with Asia Minor, and the east–west cross-desert route connecting Lebanon with the Euphrates river valley. The Anti-Lebanon Mountains mark the border between Syria and Lebanon. The range has peaks of over 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and blocks precipitation from the Mediterranean sea, so the region of Damascus is sometimes subject to droughts. However, in ancient times this was mitigated by the Barada River, which originates from mountain streams fed by melting snow. Damascus is surrounded by the Ghouta, irrigated farmland where many vegetables, cereals, and fruits have been farmed since ancient times. Maps of Roman Syria indicate that the Barada river emptied into a lake of some size east of Damascus. Today it is called Bahira Atayba, the hesitant lake because in years of severe drought, it does not even exist.[25]

The modern city has an area of 105 km2 (41 sq mi), out of which 77 km2 (30 sq mi) is urban, while Jabal Qasioun occupies the rest.[26]

.jpg.webp)

The old city of Damascus, enclosed by the city walls, lies on the south bank of the river Barada which is almost dry (3 cm (1 in) left). To the southeast, north, and north-east it is surrounded by suburban areas whose history stretches back to the Middle Ages: Midan in the southwest, Sarouja and Imara in the north and north-west. These neighborhoods originally arose on roads leading out of the city, near the tombs of religious figures. In the 19th century outlying villages developed on the slopes of Jabal Qasioun, overlooking the city, already the site of the al-Salihiyah neighborhood centered on the important shrine of medieval Andalusian Sheikh and philosopher Ibn Arabi. These new neighborhoods were initially settled by Kurdish soldiery and Muslim refugees from the European regions of the Ottoman Empire which had fallen under Christian rule. Thus they were known as al-Akrad (the Kurds) and al-Muhajirin (the migrants). They lay 2–3 km (1–2 mi) north of the old city.

From the late 19th century on, a modern administrative and commercial center began to spring up to the west of the old city, around the Barada, centered on the area known as al-Marjeh or "the meadow". Al-Marjeh soon became the name of what was initially the central square of modern Damascus, with the city hall in it. The courts of justice, post office, and railway station stood on higher ground slightly to the south. A Europeanized residential quarter soon began to be built on the road leading between al-Marjeh and al-Salihiyah. The commercial and administrative center of the new city gradually shifted northwards slightly towards this area.

In the 20th century, newer suburbs developed north of the Barada, and to some extent to the south, invading the Ghouta oasis. In 1956–1957, the new neighborhood of Yarmouk became a second home to thousands of Palestinian refugees.[27] City planners preferred to preserve the Ghouta as far as possible, and in the later 20th century some of the main areas of development were to the north, in the western Mezzeh neighborhood and most recently along the Barada valley in Dummar in the north west and on the slopes of the mountains at Barzeh in the north-east. Poorer areas, often built without official approval, have mostly developed south of the main city.

Damascus used to be surrounded by an oasis, the Ghouta region (Arabic: الغوطة, romanized: al-ġūṭä), watered by the Barada river. The Fijeh spring, west along the Barada valley, used to provide the city with drinking water and various sources to the west are tapped by water contractors. The flow of the Barada dropped with the rapid expansion of housing and industry in the city and it is almost dry. The lower aquifers are polluted by the city's runoff from heavily used roads, industry and sewage.

Climate

Damascus has a cool arid climate (BWk) in the Köppen-Geiger system,[28] due to the rain shadow effect of the Anti-Lebanon Mountains[29] and the prevailing ocean currents. Summers are prolonged, dry and hot with less humidity. Winters are cool and somewhat rainy; snowfall is infrequent. Autumn is brief and mild, but has the most drastic temperature change, unlike spring where the transition to summer is more gradual and steady. Annual rainfall is around 130 mm (5 in), occurring from October to May.

| Climate data for Damascus (Damascus International Airport) 1991–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.2 (73.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

41.4 (106.5) |

45.0 (113.0) |

45.8 (114.4) |

44.8 (112.6) |

44.6 (112.3) |

38.0 (100.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

25.1 (77.2) |

45.8 (114.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.6 (94.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

26.2 (79.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.8 (33.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.8 (12.6) |

−12 (10) |

−6 (21) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 26.0 (1.02) |

22.4 (0.88) |

13.9 (0.55) |

5.6 (0.22) |

4.8 (0.19) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.01) |

6.3 (0.25) |

21.4 (0.84) |

23.6 (0.93) |

124.7 (4.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 4.8 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 23.0 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 69 | 59 | 50 | 43 | 41 | 44 | 48 | 47 | 52 | 63 | 75 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 164.3 | 182.0 | 226.3 | 249.0 | 322.4 | 357.0 | 365.8 | 353.4 | 306.0 | 266.6 | 207.0 | 164.3 | 3,164.1 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.3 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 11.4 | 10.2 | 8.6 | 6.9 | 5.3 | 8.5 |

| Source: NOAA[30] | |||||||||||||

History

Early settlement

Carbon-14 dating at Tell Ramad, on the outskirts of Damascus, suggests that the site may have been occupied since the second half of the seventh millennium BC, possibly around 6300 BC.[31] However, evidence of settlement in the wider Barada basin dating back to 9000 BC exists, although no large-scale settlement was present within Damascus' walls until the second millennium BC.[32]

Late Bronze

Some of the earliest Egyptian records are from the 1350 BC Amarna letters, when Damascus (called Dimasqu) was ruled by king Biryawaza. The Damascus region, as well as the rest of Syria, became a battleground circa 1260 BC, between the Hittites from the north and the Egyptians from the south,[33] ending with a signed treaty between Hattusili III and Ramesses II where the former handed over control of the Damascus area to Ramesses II in 1259 BC.[33] The arrival of the Sea Peoples, around 1200 BC, marked the end of the Bronze Age in the region and brought about new development of warfare.[34] Damascus was only a peripheral part of this picture, which mostly affected the larger population centers of ancient Syria. However, these events contributed to the development of Damascus as a new influential center that emerged with the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age.[34]

Damascus is mentioned in Genesis 14:15 as existing at the time of the War of the Kings.[35] According to the 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in his twenty-one volume Antiquities of the Jews, Damascus (along with Trachonitis), was founded by Uz, the son of Aram.[36] In Antiquities i. 7,[37] Josephus reports:

Nicolaus of Damascus, in the fourth book of his History, says thus: "Abraham reigned at Damascus, being a foreigner, who came with an army out of the land above Babylon, called the land of the Chaldeans: but, after a long time, he got him up, and removed from that country also, with his people, and went into the land then called the land of Canaan, but now the land of Judea, and this when his posterity were become a multitude; as to which posterity of his, we relate their history in another work. Now the name of Abraham is even still famous in the country of Damascus; and there is shown a village named from him, The Habitation of Abraham.

Aram-Damascus

Damascus is first documented as an important city during the arrival of the Aramaeans, a Semitic people, in the 11th century BC. By the start of the first millennium BC, several Aramaic kingdoms were formed, as Aramaeans abandoned their nomadic lifestyle and formed federated tribal states. One of these kingdoms was Aram-Damascus, centered on its capital Damascus.[39] The Aramaeans who entered the city without battle, adopted the name "Dimashqu" for their new home. Noticing the agricultural potential of the still-undeveloped and sparsely populated area,[40] they established the water distribution system of Damascus by constructing canals and tunnels which maximized the efficiency of the river Barada. The same network was later improved by the Romans and the Umayyads, and still forms the basis of the water system of the old part of the city today.[41] The Aramaeans initially turned Damascus into an outpost of a loose federation of Aramaean tribes, known as Aram-Zobah, based in the Beqaa Valley.[40]

The city would gain pre-eminence in southern Syria when Ezron, the claimant to Aram-Zobah's throne who was denied kingship of the federation, fled Beqaa and captured Damascus by force in 965 BC. Ezron overthrew the city's tribal governor and founded the independent entity of Aram-Damascus. As this new state expanded south, it prevented the Kingdom of Israel from spreading north and the two kingdoms soon clashed as they both sought to dominate trading hegemony in the east.[40] Under Ezron's grandson, Ben-Hadad I (880–841 BC), and his successor Hazael, Damascus annexed Bashan (modern-day Hauran region), and went on the offensive with Israel. This conflict continued until the early 8th century BC when Ben-Hadad II was captured by Israel after unsuccessfully besieging Samaria. As a result, he granted Israel trading rights in Damascus.[42]

Another possible reason for the treaty between Aram-Damascus and Israel was the common threat of the Neo-Assyrian Empire which was attempting to expand into the Mediterranean coast. In 853 BC, King Hadadezer of Damascus led a Levantine coalition, that included forces from the northern Aram-Hamath kingdom and troops supplied by King Ahab of Israel, in the Battle of Qarqar against the Neo-Assyrian army. Aram-Damascus came out victorious, temporarily preventing the Assyrians from encroaching into Syria. However, after Hadadzezer was killed by his successor, Hazael, the Levantine alliance collapsed. Aram-Damascus attempted to invade Israel, but was interrupted by the renewed Assyrian invasion. Hazael ordered a retreat to the walled part of Damascus while the Assyrians plundered the remainder of the kingdom. Unable to enter the city, they declared their supremacy in the Hauran and Beqa'a valleys.[42]

By the 8th century BC, Damascus was practically engulfed by the Assyrians and entered a Dark Age. Nonetheless, it remained the economic and cultural center of the Near East as well as the Arameaen resistance. In 727, a revolt took place in the city, but was put down by Assyrian forces. After Assyria led by Tiglath-Pileser III went on a wide-scale campaign of quelling revolts throughout Syria, Damascus became totally subjugated by their rule. A positive effect of this was stability for the city and benefits from the spice and incense trade with Arabia. In 694 BC, the town was called Šaʾimerišu (Akkadian: 𒐼𒄿𒈨𒊑𒋙𒌋) and its governor was named Ilu-issīya.[43] However, Assyrian authority was dwindling by 609–605 BC, and Syria-Palestine was falling into the orbit of Pharaoh Necho II's Egypt. In 572 BC, all of Syria had been conquered by Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonians, but the status of Damascus under Babylon is relatively unknown.[44]

Hellenistic period

Damascus was conquered by Alexander the Great. After the death of Alexander in 323 BC, Damascus became the site of a struggle between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires. The control of the city passed frequently from one empire to the other. Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander's generals, made Antioch the capital of his vast empire, which led to the decline of Damascus' importance compared with new Seleucid cities such as Syrian Laodicea in the north. Later, Demetrius III Philopator rebuilt the city according to the Greek hippodamian system and renamed it "Demetrias".[45]

Roman period

In 64 BC, the Roman general Pompey annexed the western part of Syria. The Romans occupied Damascus and subsequently incorporated it into the league of ten cities known as the Decapolis[46] which themselves were incorporated into the province of Syria and granted autonomy.[47]

The city of Damascus was entirely redesigned by the Romans after Pompey conquered the region. Still today the Old Town of Damascus retains the rectangular shape of the Roman city, with its two main axes: the Decumanus Maximus (east-west; known today as the Via Recta) and the Cardo (north-south), the Decumanus being about twice as long. The Romans built a monumental gate which still survives at the eastern end of Decumanus Maximus. The gate originally had three arches: the central arch was for chariots while the side arches were for pedestrians.[25]

In 23 BC, Herod the Great was given lands controlled by Zenodorus by Caesar Augustus[48] and some scholars believe that Herod was also granted control of Damascus as well.[49] The control of Damascus reverted to Syria either upon the death of Herod the Great or was part of the lands given to Herod Philip which were given to Syria with his death in 33/34 AD.

It is speculated that control of Damascus was gained by Aretas IV Philopatris of Nabatea between the death of Herod Philip in 33/34 AD and the death of Aretas in 40 AD but there is substantial evidence against Aretas controlling the city before 37 AD and many reasons why it could not have been a gift from Caligula between 37 and 40 AD.[50][51] In fact, all these theories stem not from any actual evidence outside the New Testament but rather "a certain understanding of 2 Corinthians 11:32" and in reality "neither from archaeological evidence, secular-historical sources, nor New Testament texts can Nabatean sovereignty over Damascus in the first century AD be proven."[52] Roman emperor Trajan who annexed the Nabataean Kingdom, creating the province of Arabia Petraea, had previously been in Damascus, as his father Marcus Ulpius Traianus served as governor of Syria from 73 to 74 AD, where he met the Nabatean architect and engineer, Apollodorus of Damascus, who joined him in Rome when he was a consul in 91 AD, and later built several monuments during the 2nd century AD.[53]

Damascus became a metropolis by the beginning of the 2nd century and in 222 it was upgraded to a colonia by the Emperor Septimius Severus. During the Pax Romana, Damascus and the Roman province of Syria in general began to prosper. Damascus's importance as a caravan city was evident with the trade routes from southern Arabia, Palmyra, Petra, and the silk routes from China all converging on it. The city satisfied the Roman demands for eastern luxuries. Circa 125 AD the Roman emperor Hadrian promoted the city of Damascus to "Metropolis of Coele-Syria".[54][55]

Little remains of the architecture of the Romans, but the town planning of the old city did have a lasting effect. The Roman architects brought together the Greek and Aramaean foundations of the city and fused them into a new layout measuring approximately 1,500 by 750 m (4,920 by 2,460 ft), surrounded by a city wall. The city wall contained seven gates, but only the eastern gate, Bab Sharqi, remains from the Roman period. Roman Damascus lies mostly at depths of up to five meters (16 feet) below the modern city.

The old borough of Bab Tuma was developed at the end of the Roman/Byzantine era by the local Eastern Orthodox community. According to the Acts of the Apostles, Saint Paul and Saint Thomas both lived in that neighborhood. Roman Catholic historians also consider Bab Tuma to be the birthplace of several Popes such as John V and Gregory III. Accordingly, there was a community of Jewish Christians who converted to Christianity with the advent of Saint Paul's proselytisation.

During the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, the city was besieged and captured by Shahrbaraz in 613, along with a large number of Byzantine troops as prisoners,[56] and was in Sasanian hands until near the end of the war.[57]

Rashidun period

Muhammad's first indirect interaction with the people of Damascus was when he sent a letter, through his companion Shiya ibn Wahab, to Harith ibn Abi Shamir, the king of Damascus. In his letter, Muhammad stated: "Peace be upon him who follows true guidance. Be informed that my religion shall prevail everywhere. You should accept Islam, and whatever under your command shall remain yours."[58][59]

After most of the Syrian countryside was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate during the reign of Caliph Umar (r. 634–644), Damascus itself was conquered by the Arab Muslim general Khalid ibn al-Walid in August–September 634 CE. His army had previously attempted to capture the city in April 634, but without success.[60] With Damascus now in Muslim-Arab hands, the Byzantines, alarmed at the loss of their most prestigious city in the Near East, had decided to wrest back control of it. Under Emperor Heraclius, the Byzantines fielded an army superior to that of the Rashidun in manpower. They advanced into southern Syria during the spring of 636 and consequently Khalid ibn al-Walid's forces withdrew from Damascus to prepare for renewed confrontation.[61] In August, the two sides met along the Yarmouk River where they fought a major battle which ended in a decisive Muslim victory, solidifying Muslim rule in Syria and Palestine.[62] While the Muslims administered the city, the population of Damascus remained mostly Christian—Eastern Orthodox and Monophysite—with a growing community of Muslims from Mecca, Medina, and the Syrian Desert.[63] The governor assigned to the city which had been chosen as the capital of Islamic Syria was Mu'awiya I.

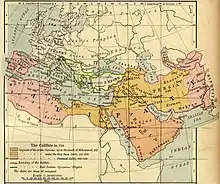

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

Following the fourth Rashidun caliph Ali's death in 661, Mu'awiya was chosen as the caliph of the expanding Islamic empire. Because of the vast amounts of assets his clan, the Umayyads, owned in the city and because of its traditional economic and social links with the Hijaz as well as the Christian Arab tribes of the region, Mu'awiya established Damascus as the capital of the entire Caliphate.[64] With the ascension of Caliph Abd al-Malik in 685, an Islamic coinage system was introduced and all of the surplus revenue of the Caliphate's provinces were forwarded to the treasury of Damascus. Arabic was also established as the official language, giving the Muslim minority of the city an advantage over the Aramaic-speaking Christians in administrative affairs.[65]

Abd al-Malik's successor, al-Walid initiated construction of the Grand Mosque of Damascus (known as the Umayyad Mosque) in 706. The site originally had been the Christian Cathedral of St. John and the Muslims maintained the building's dedication to John the Baptist.[66] By 715, the mosque was complete. Al-Walid died that same year and he was succeeded at first by Suleiman ibn Abd al-Malik and then by Umar II, who each ruled for brief periods before the reign of Hisham in 724. With these successions, the status of Damascus was gradually weakening as Suleiman had chosen Ramla as his residence and later Hisham chose Resafa. Following the murder of the latter in 743, the Caliphate of the Umayyads—which by then stretched from Spain to India— was crumbling as a result of widespread revolts. During the reign of Marwan II in 744, the capital of the empire was relocated to Harran in the northern Jazira region.[67]

On 25 August 750, the Abbasids, having already beaten the Umayyads in the Battle of the Zab in Iraq, conquered Damascus after facing little resistance. With the heralding of the Abbasid Caliphate, Damascus became eclipsed and subordinated by Baghdad, the new Islamic capital. Within the first six months of Abbasid rule, revolts began erupting in the city, albeit too isolated and unfocused to present a viable threat. Nonetheless, the last of the prominent Umayyads were executed, the traditional officials of Damascus ostracised, and army generals from the city were dismissed. Afterwards, the Umayyad family cemetery was desecrated and the city walls were torn down, reducing Damascus into a provincial town of little importance. It roughly disappeared from written records for the next century and the only significant improvement of the city was the Abbasid-built treasury dome in the Umayyad Mosque in 789. In 811, distant remnants of the Umayyad dynasty staged a strong uprising in Damascus that was eventually put down.[68]

Ahmad ibn Tulun, a dissenting Turkish governor appointed by the Abbasids, conquered Syria, including Damascus, from his overlords in 878–79. In an act of respect for the previous Umayyad rulers, he erected a shrine on the site of Mu'awiya's grave in the city. Tulunid rule of Damascus was brief, lasting only until 906 before being replaced by the Qarmatians who were adherents of Shia Islam. Due to their inability to control the vast amount of land they occupied, the Qarmatians withdrew from Damascus and a new dynasty, the Ikhshidids, took control of the city. They maintained the independence of Damascus from the Arab Hamdanid dynasty of Aleppo and the Baghdad-based Abbasids until 967. A period of instability in the city followed, with a Qarmatian raid in 968, a Byzantine raid in 970, and increasing pressures from the Fatimids in the south and the Hamdanids in the north.[69]

The Shia Fatimids gained control in 970, inflaming hostilities between them and the Sunni Arabs of the city who frequently revolted. A Turk, Alptakin drove out the Fatimids five years later, and through diplomacy, prevented the Byzantines during the Syrian campaigns of John Tzimiskes from attempting to annex the city. However, by 977, the Fatimids under Caliph al-Aziz, wrested back control of the city and tamed Sunni dissidents. The Arab geographer, al-Muqaddasi, visited Damascus in 985, remarking that the architecture and infrastructure of the city was "magnificent", but living conditions were awful. Under al-Aziz, the city saw a brief period of stability that ended with the reign of al-Hakim (996–1021). In 998, hundreds of Damascus' citizens were rounded up and executed by him for incitement. Three years after al-Hakim's mysterious disappearance, the Arab tribes of southern Syria formed an alliance to stage a massive rebellion against the Fatimids, but they were crushed by the Fatimid Turkish governor of Syria and Palestine, Anushtakin al-Duzbari, in 1029. This victory gave the latter mastery over Syria, displeasing his Fatimid overlords, but gaining the admiration of Damascus' citizens. He was exiled by Fatimid authorities to Aleppo where he died in 1041.[70] From that date to 1063, there are no known records of the city's history. By then, Damascus lacked a city administration, had an enfeebled economy, and a greatly reduced population.[71]

Seljuq and Ayyubid periods

With the arrival of the Seljuq Turks in the late 11th century, Damascus again became the capital of independent states. It was ruled by Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I starting in 1079 and he was succeeded by his son Abu Nasr Duqaq in 1095. The Seljuqs established a court in Damascus and a systematic reversal of Shia inroads in the city. The city also saw an expansion of religious life through private endowments financing religious institutions (madrasas) and hospitals (maristans). Damascus soon became one of the most important centers of propagating Islamic thought in the Muslim world. After Duqaq's death in 1104, his mentor (atabeg), Toghtekin, took control of Damascus and the Burid line of the Seljuq dynasty. Under Duqaq and Toghtekin, Damascus experienced stability, elevated status and a revived role in commerce. In addition, the city's Sunni majority enjoyed being a part of the larger Sunni framework effectively governed by various Turkic dynasties who in turn were under the moral authority of the Baghdad-based Abbasids.[72]

While the rulers of Damascus were preoccupied in conflict with their fellow Seljuqs in Aleppo and Diyarbakir, the Crusaders, who arrived in the Levant in 1097, conquered Jerusalem, Mount Lebanon and Palestine. Duqaq seemed to have been content with Crusader rule as a buffer between his dominion and the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. Toghtekin, however, saw the Western invaders as a viable threat to Damascus which, at the time, nominally included Homs, the Beqaa Valley, Hauran, and the Golan Heights as part of its territories. With military support from Sharaf al-Din Mawdud of Mosul, Toghtekin managed to halt Crusader raids in the Golan and Hauran. Mawdud was assassinated in the Umayyad Mosque in 1109, depriving Damascus of northern Muslim backing and forcing Toghtekin to agree to a truce with the Crusaders in 1110.[73] In 1126, the Crusader army led by Baldwin II fought Burid forces led by Toghtekin at Marj al-Saffar near Damascus; however, despite their tactical victory, the Crusaders failed in their objective to capture Damascus.

Following Toghtekin's death in 1128, his son, Taj al-Muluk Buri, became the nominal ruler of Damascus. Coincidentally, the Seljuq prince of Mosul, Imad al-Din Zengi, took power in Aleppo and gained a mandate from the Abbasids to extend his authority to Damascus. In 1129, around 6,000 Isma'ili Muslims were killed in the city along with their leaders. The Sunnis were provoked by rumors alleging there was a plot by the Isma'ilis, who controlled the strategic fort at Banias, to aid the Crusaders in capturing Damascus in return for control of Tyre. Soon after the massacre, the Crusaders aimed to take advantage of the unstable situation and launch an assault against Damascus with nearly 2,000 knights and 10,000 infantry. However, Buri allied with Zengi and managed to prevent their army from reaching the city.[76] Buri was assassinated by Isma'ili agents in 1132; he was succeeded by his son, Shams al-Mulk Isma'il who ruled tyrannically until he himself was murdered in 1135 on secret orders from his mother, Safwat al-Mulk Zumurrud; Isma'il's brother, Shihab al-Din Mahmud, replaced him. Meanwhile, Zengi, intent on putting Damascus under his control, married Safwat al-Mulk in 1138. Mahmud's reign then ended in 1139 after he was killed for relatively unknown reasons by members of his family. Mu'in al-Din Unur, his mamluk ("slave soldier") took effective power of the city, prompting Zengi—with Safwat al-Mulk's backing—to lay siege against Damascus the same year. In response, Damascus allied with the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem to resist Zengi's forces. Consequently, Zengi withdrew his army and focused on campaigns against northern Syria.[77]

In 1144, Zengi conquered Edessa, a crusader stronghold, which led to a new crusade from Europe in 1148. In the meantime Zengi was assassinated and his territory was divided among his sons, one of whom, Nur ad-Din, emir of Aleppo, made an alliance with Damascus. When the European crusaders arrived, they and the nobles of Jerusalem agreed to attack Damascus. Their siege, however, was a complete failure. When the city seemed to be on the verge of collapse, the crusader army suddenly moved against another section of the walls, and were driven back. By 1154, Damascus was firmly under Nur ad-Din's control.[78]

In 1164, King Amalric of Jerusalem invaded Fatimid Egypt, which requested help from Nur ad-Din. The Nur ad-Din sent his general Shirkuh, and in 1166 Amalric was defeated at the Battle of al-Babein. When Shirkuh died in 1169, he was succeeded by his nephew Yusuf, better known as Saladin, who defeated a joint crusader-Byzantine siege of Damietta.[79] Saladin eventually overthrew the Fatimid caliphs and established himself as Sultan of Egypt. He also began to assert his independence from Nur ad-Din, and with the death of both Amalric and Nur ad-Din in 1174, he was well-placed to begin exerting control over Damascus and Nur ad-Din's other Syrian possessions.[80] In 1177 Saladin was defeated by the crusaders at the Battle of Montgisard, despite his numerical superiority.[81] Saladin also besieged Kerak in 1183, but was forced to withdraw. He finally launched a full invasion of Jerusalem in 1187, and annihilated the crusader army at the Battle of Hattin in July. Acre fell to Saladin soon after, and Jerusalem itself was captured in October. These events shocked Europe, resulting in the Third Crusade in 1189, led by Richard I of England, Philip II of France and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor, though the last drowned en route.[82]

The surviving crusaders, joined by new arrivals from Europe, put Acre to a lengthy siege which lasted until 1191. After re-capturing Acre, Richard defeated Saladin at the Battle of Arsuf in 1191 and the Battle of Jaffa in 1192, recovering most of the coast for the Christians, but could not recover Jerusalem or any of the inland territory of the kingdom. The crusade came to an end peacefully, with the Treaty of Jaffa in 1192. Saladin allowed pilgrimages to be made to Jerusalem, allowing the crusaders to fulfil their vows, after which they all returned home. Local crusader barons set about rebuilding their kingdom from Acre and the other coastal cities.[83]

Saladin died in 1193, and there were frequent conflicts between different Ayyubid sultans ruling in Damascus and Cairo. Damascus was the capital of independent Ayyubid rulers between 1193 and 1201, from 1218 to 1238, from 1239 to 1245, and from 1250 to 1260. At other times it was ruled by the Ayyubid rulers of Egypt.[84] During the internecine wars fought by the Ayyubid rulers, Damascus was besieged repeatedly, as, e.g., in 1229.[85]

The patterned Byzantine and Chinese silks available through Damascus, one of the Western termini of the Silk Road, gave the English language "damask".[86]

Mamluk period

Ayyubid rule (and independence) came to an end with the Mongol invasion of Syria in 1260, in which the Mongols led by Kitbuqa entered the city on 1 March 1260, along with the King of Armenia, Hethum I, and the Prince of Antioch, Bohemond VI; hence, the citizens of Damascus saw for the first time for six centuries three Christian potentates ride in triumph through their streets.[87] However, following the Mongol defeat at Ain Jalut on 3 September 1260, Damascus was captured five days later and became the provincial capital of the Mamluk Sultanate, ruled from Egypt, following the Mongol withdrawal. Following their victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khaznadar, the Mongols led by Ghazan besieged the city for ten days, which surrendered between December 30, 1299, and January 6, 1300, though its Citadel resisted.[88] Ghazan then retreated with most of his forces in February, probably because the Mongol horses needed fodder, and left behind about 10,000 horsemen under the Mongol general Mulay.[89] Around March 1300, Mulay returned with his horsemen to Damascus,[90] then followed Ghazan back across the Euphrates. In May 1300, the Egyptian Mamluks returned from Egypt and reclaimed the entire area[91] without a battle.[92] In April 1303, the Mamluks managed to defeat the Mongol army led by Kutlushah and Mulay along with their Armenian allies at the Battle of Marj al-Saffar, to put an end to Mongol invasions of the Levant.[93] Later on, the Black Death of 1348–1349 killed as much as half of the city's population.[94]

In 1400, Timur, the Turco-Mongol conqueror, besieged Damascus. The Mamluk sultan dispatched a deputation from Cairo, including Ibn Khaldun, who negotiated with him, but after their withdrawal Timur sacked the city on 17 March 1401.[95] The Umayyad Mosque was burnt and men and women taken into slavery. A huge number of the city's artisans were taken to Timur's capital at Samarkand. These were the luckier citizens: many were slaughtered and their heads piled up in a field outside the north-east corner of the walls, where a city square still bears the name Burj al-Ru'us (between modern-day Al-Qassaa and Bab Tuma), originally "the tower of heads".

Rebuilt, Damascus continued to serve as a Mamluk provincial capital until 1516.

Ottoman period

In early 1516, the Ottoman Empire, wary of the danger of an alliance between the Mamluks and the Persian Safavids, started a campaign of conquest against the Mamluk sultanate. On 21 September, the Mamluk governor of Damascus fled the city, and on 2 October the khutba in the Umayyad mosque was pronounced in the name of Selim I. The day after, the victorious sultan entered the city, staying for three months. On 15 December, he left Damascus by Bab al-Jabiya, intent on the conquest of Egypt. Little appeared to have changed in the city: one army had simply replaced another. However, on his return in October 1517, the sultan ordered the construction of a mosque, tekkiye and mausoleum at the shrine of Shaikh Muhi al-Din ibn Arabi in al-Salihiyah. This was to be the first of Damascus' great Ottoman monuments. During this time, according to an Ottoman census, Damascus had 10,423 households.[96]

The Ottomans remained for the next 400 years, except for a brief occupation by Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt from 1832 to 1840. Because of its importance as the point of departure for one of the two great Hajj caravans to Mecca, Damascus was treated with more attention by the Porte than its size might have warranted—for most of this period, Aleppo was more populous and commercially more important. In 1559 the western building of Sulaymaniyya Takiyya, comprising a mosque and khan for pilgrims on the road to Mecca, was completed to a design by the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan, and soon afterwards the Salimiyya Madrasa was built adjoining it.[97]

Early in the nineteenth century, Damascus was noted for its shady cafes along the banks of the Barada. A depiction of these by William Henry Bartlett was published in 1836, along with a poetical illustration by Letitia Elizabeth Landon, see ![]() Cafes in Damascus.. Under Ottoman rule, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis and were allowed to practice their religious precepts. During the Damascus affair of 1840 the false accusation of ritual murder was brought against members of the Jewish community of Damascus. The massacre of Christians in 1860 was also one of the most notorious incidents of these centuries, when fighting between Druze and Maronites in Mount Lebanon spilled over into the city. Several thousand Christians were killed in June 1860, with many more being saved through the intervention of the Algerian exile Abd al-Qadir and his soldiers (three days after the massacre started), who brought them to safety in Abd al-Qadir's residence and the Citadel of Damascus. The Christian quarter of the old city (mostly inhabited by Catholics), including a number of churches, was burnt down. The Christian inhabitants of the notoriously poor and refractory Midan district outside the walls (mostly Orthodox) were, however, protected by their Muslim neighbors.

Cafes in Damascus.. Under Ottoman rule, Christians and Jews were considered dhimmis and were allowed to practice their religious precepts. During the Damascus affair of 1840 the false accusation of ritual murder was brought against members of the Jewish community of Damascus. The massacre of Christians in 1860 was also one of the most notorious incidents of these centuries, when fighting between Druze and Maronites in Mount Lebanon spilled over into the city. Several thousand Christians were killed in June 1860, with many more being saved through the intervention of the Algerian exile Abd al-Qadir and his soldiers (three days after the massacre started), who brought them to safety in Abd al-Qadir's residence and the Citadel of Damascus. The Christian quarter of the old city (mostly inhabited by Catholics), including a number of churches, was burnt down. The Christian inhabitants of the notoriously poor and refractory Midan district outside the walls (mostly Orthodox) were, however, protected by their Muslim neighbors.

American Missionary E.C. Miller records that in 1867 the population of the city was 'about' 140,000, of whom 30,000 were Christians, 10,000 Jews and 100,000 'Mohammedans' with fewer than 100 Protestant Christians.[98] In the meantime, American writer Mark Twain visited Damascus, then wrote about his travel in The Innocents Abroad, in which he mentioned: "Though old as history itself, thou art fresh as the breath of spring, blooming as thine own rose-bud, and fragrant as thine own orange flower, O Damascus, pearl of the East!".[99] In November 1898, German emperor Wilhelm II toured Damascus, during his trip to the Ottoman Empire.[100]

20th century

In the early years of the 20th century, nationalist sentiment in Damascus, initially cultural in its interest, began to take a political coloring, largely in reaction to the turkicisation program of the Committee of Union and Progress government established in Istanbul in 1908. The hanging of a number of patriotic intellectuals by Jamal Pasha, governor of Damascus, in Beirut and Damascus in 1915 and 1916 further stoked nationalist feeling, and in 1918, as the forces of the Arab Revolt and the British Imperial forces approached, residents fired on the retreating Turkish troops.

On 1 October 1918, T.E. Lawrence entered Damascus, the third arrival of the day, the first being the Australian 3rd Light Horse Brigade, led by Major A.C.N. 'Harry' Olden.[101] Two days later, 3 October 1918, the forces of the Arab revolt led by Prince Faisal also entered Damascus.[102] A military government under Shukri Pasha was named and Faisal ibn Hussein was proclaimed king of Syria. Political tension rose in November 1917, when the new Bolshevik government in Russia revealed the Sykes-Picot Agreement whereby Britain and France had arranged to partition the Arab east between them. A new Franco-British proclamation on 17 November promised the "complete and definitive freeing of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks." The Syrian National Congress in March adopted a democratic constitution. However, the Versailles Conference had granted France a mandate over Syria, and in 1920 a French army commanded by the General Mariano Goybet crossed the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, defeated a small Syrian defensive expedition at the Battle of Maysalun and entered Damascus. The French made Damascus capital of their League of Nations Mandate for Syria.

When in 1925 the Great Syrian Revolt in the Hauran spread to Damascus, the French suppressed with heavy weaponry, bombing and shelling the city on 9 May 1926. As a result, the area of the old city between Al-Hamidiyah Souq and Medhat Pasha Souq was burned to the ground, with many deaths, and has since then been known as al-Hariqa ("the fire"). The old city was surrounded with barbed wire to prevent rebels infiltrating from the Ghouta, and a new road was built outside the northern ramparts to facilitate the movement of armored cars.

On 21 June 1941, 3 weeks into the Allied Syria-Lebanon campaign, Damascus was captured from the Vichy French forces by a mixed British Indian and Free French force. The French agreed to withdraw in 1946, following the British intervention during the Levant Crisis, thus leading to the full independence of Syria. Damascus remained the capital.

Civil war

By January 2012, clashes between the regular army and rebels reached the outskirts of Damascus, reportedly preventing people from leaving or reaching their houses, especially when security operations there intensified from the end of January into February.[103]

By June 2012, bullets and shrapnel shells smashed into homes in Damascus overnight as troops battled the Free Syrian Army in the streets. At least three tank shells slammed into residential areas in the central Damascus neighborhood of Qaboun, according to activists. Intense exchanges of assault-rifle fire marked the clash, according to residents and amateur video posted online.[104]

The Damascus suburb of Ghouta suffered heavy bombing in December 2017 and a further wave of bombing started in February 2018, also known as Rif Dimashq Offensive.

On 20 May 2018, Damascus and the entire Rif Dimashq Governorate came fully under government control for the first time in 7 years after the evacuation of IS from Yarmouk Camp.[105] In September 2019, Damascus entered the Guinness World Records as the least liveable city, scoring 30.7 points on the Economist's Global Liveability Index in 2019, based on factors such as: stability, healthcare, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure.[106] However, the trend of being the least liveable city on Earth started in 2017,[107] and continued as of 2023.[108]

Economy

The historical role that Damascus played as an important trade center has changed in recent years due to political development in the region as well as the development of modern trade.[2] Most goods produced in Damascus, as well as in Syria, are distributed to countries of the Arabian peninsula.[2] Damascus has also held an annual international trade exposition every fall, since 1954.[109]

The tourism industry in Damascus has a lot of potential, however the civil war has hampered these prospects. The abundance of cultural wealth in Damascus has been modestly employed since the late 1980s with the development of many accommodation and transportation establishments and other related investments.[2] Since the early 2000s, numerous boutique hotels and bustling cafes opened in the old city which attract plenty of European tourists and Damascenes alike.[110]

In 2009 new office space was built and became available on the real estate market.[111]

Damascus is home to a wide range of industrial activity, such as textile, food processing, cement and various chemical industries.[2] The majority of factories are run by the state, however limited privatization in addition to economic activities led by the private sector, were permitted starting in the early 2000s with the liberalization of trade that took place.[2] Traditional handcrafts and artisan copper engravings are still produced in the old city.[2]

The Damascus stock exchange formally opened for trade in March 2009, and the exchange is the only stock exchange in Syria.[112] It is located in the Barzeh district, within Syria's financial markets and securities commission. Its final home is to be located in the upmarket business district of Yaafur.[113]

Demographics

Population

Damascus's population in 2004 was estimated to be 2.7 million people.[114] The estimated population of Damascus in 2011 was 1,711,000. However, in 2022, the city had an estimated population of 2,503,000, which in early 2023 rose to 2,584,771.[115]

Damascus is the center of a crowded metropolitan area with an estimated population of 5 million. The metropolitan area of Damascus includes the cities of Douma, Harasta, Darayya, Al-Tall and Jaramana.

The city's growth rate is higher than Syria as a whole, primarily due to rural-urban migration and the influx of young Syrian migrants drawn by employment and educational opportunities.[116] The migration of Syrian youths to Damascus has resulted in an average age within the city that is below the national average.[116] Nonetheless, the population of Damascus is thought to have decreased in recent years as a result of the ongoing Syrian civil war.

Ethnicity

The vast majority of Damascenes are Syrian Arabs. The Kurds are the second largest ethnic minority, with a population of approximately 300,000.[117] They reside primarily in the neighborhoods of Wadi al-Mashari ("Zorava" or "Zore Afa" in Kurdish) and Rukn al-Din.[118][119] Other minorities include Palestinians, Assyrians, Syrian Turkmen, Armenians, Circassians and a small Greek community.

There was once a significant Jewish community in Damascus, but as of 2023, only a few elderly Jews remain.[120]

Religion

Islam is the largest religion. The majority of Muslims are Sunni while Alawites and Twelver Shi'a comprise sizeable minorities. Alawites live primarily in the Mezzeh districts of Mezzeh 86 and Sumariyah. Twelvers primarily live near the Shia holy sites of Sayyidah Ruqayya and Sayyidah Zaynab. It is believed that there are more than 200 mosques in Damascus, the most well-known being the Umayyad Mosque.[121]

Christians represent about 10%–15% of the population. Several Eastern Christian rites have their headquarters in Damascus, including the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Syriac Catholic Church, and the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch. The Christian districts in the city are Bab Tuma, Qassaa and Ghassani. Each have many churches, most notably the ancient Chapel of Saint Paul and St Georges Cathedral in Bab Tuma. At the suburb of Soufanieh a series of apparitions of the Virgin Mary have reportedly been observed between 1982 and 2004.[122] The Patriarchal See of the Syriac Orthodox is based in Damascus, Bab Touma.

A smaller Druze minority inhabits the city, notably in the mixed Christian-Druze suburbs of Tadamon,[123] Jaramana,[124] and Sahnaya.

There was a small Jewish community namely in what is called Harat al-Yahud the Jewish quarter. They are the remnants of an ancient and much larger Jewish presence in Syria, dating back at least to Roman times, if not before to the time of King David.[125]

Gallery

.jpg.webp)

The Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque

Sufism

Sufism throughout the second half of the 20th century has been an influential current in the Sunni religious practises, particularly in Damascus. The largest women-only and girls-only Muslim movement in the world happens to be Sufi-oriented and is based in Damascus, led by Munira al-Qubaysi. Syrian Sufism has its stronghold in urban regions such as Damascus, where it also established political movements such as Zayd, with the help of a series of mosques, and clergy such as Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi, Sa'id Hawwa, Abd al-Rahman al-Shaghouri and Muhammad al-Yaqoubi.[126]

Historical sites

Damascus has a wealth of historical sites dating back to many different periods of the city's history. Since the city has been built up with every passing occupation, it has become almost impossible to excavate all the ruins of Damascus that lie up to 2.4 m (8 ft) below the modern level. The Citadel of Damascus is in the northwest corner of the Old City. The Damascus Straight Street (referred to in the account of the conversion of St. Paul in Acts 9:11), also known as the Via Recta, was the decumanus (east–west main street) of Roman Damascus, and extended for over 1,500 m (4,900 ft). Today, it consists of the street of Bab Sharqi and the Souk Medhat Pasha, a covered market. The Bab Sharqi street is filled with small shops and leads to the old Christian quarter of Bab Tuma (St. Thomas's Gate), where St George's Cathedral, the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Church, is notably located. Medhat Pasha Souq is also a main market in Damascus and was named after Midhat Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Syria who renovated the Souk. At the end of the Bab Sharqi street, one reaches the House of Ananias, an underground chapel that was the cellar of Ananias's house. The Umayyad Mosque, also known as the Grand Mosque of Damascus, is one of the largest mosques in the world and also one of the oldest sites of continuous prayer since the rise of Islam. A shrine in the mosque is said to contain the body of St. John the Baptist. The mausoleum where Saladin was buried is located in the gardens just outside the mosque. Sayyidah Ruqayya Mosque, the shrine of the youngest daughter of Husayn ibn Ali, can also be found near the Umayyad Mosque. The ancient district of Amara is also within a walking distance from these sites. Another heavily visited site is Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque, where the tomb of Zaynab bint Ali is located.

Shias, Fatemids and Dawoodi Bohras believe that after the battle of Karbala (680 AD), in Iraq, the Umayyad Caliph Yezid brought Imam Husain's head to Damascus, where it was first kept in the courtyard of Yezid Mahal, now part of Umayyad Mosque complex. All other remaining members of Imam Husain's family (left alive after Karbala) along with heads of all other companions, who were killed at Karbala, were also brought to Damascus. These members were kept as prisoners on the outskirts of the city (near Bab al-Saghir), where the other heads were kept at the same location, now called Ru'ûs ash-Shuhadâ-e-Karbala or ganj-e-sarha-e-shuhada-e-Karbala.[127] There is a qibla (place of worship) marked at the place, where devotees say Imam Ali-Zain-ul-Abedin used to pray while in captivity.

The Harat Al Yehud[128] or Jewish Quarter is a recently restored historical tourist destination popular among Europeans before the outbreak of civil war.

Walls and gates of Damascus

The Old City of Damascus with an approximate area of 86.12 hectares[129] is surrounded by ramparts on the northern and eastern sides and part of the southern side. There are seven extant city gates, the oldest of which dates back to the Roman period. These are, clockwise from the north of the citadel:

- Bab al-Faradis ("the gate of the orchards", or "of the paradise")

- Bab al-Salam ("the gate of peace"), all on the north boundary of the Old City

- Bab Tuma ("Touma" or "Thomas's Gate") in the north-east corner, leading into the Christian quarter of the same name,

- Bab Sharqi ("eastern gate") in the east wall, the only one to retain its Roman plan

- Bab Kisan in the south-east, from which tradition holds that Saint Paul made his escape from Damascus, lowered from the ramparts in a basket; this gate has been closed and turned into Chapel of Saint Paul marking this event,

- Bab al-Saghir (The Small Gate)

- Bab al-Jabiya at the entrance to Souk Midhat Pasha, in the south-west.

Other areas outside the walled city also bear the name "gate": Bab al-Faraj, Bab Mousalla and Bab Sreija, both to the south-west of the walled city.

Churches in the old city

- Chapel of Saint Paul

- House of Saint Ananias

- Mariamite Cathedral of Damascus

- Cathedral of the Dormition of Our Lady

- Saint John the Damascene Church

- Saint Paul's Laura

- Saint George's Syriac Orthodox Cathedral

Islamic sites in the old city

- Umayyad Mosque, also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus

- Sayyidah Ruqayya Mosque

- Bab Saghir Cemetery

- Mausoleum of Saladin

- Nabi Habeel Mosque

Old Damascene houses

- Azm Palace, originally built in 1750 as the residence for the Ottoman governor of Damascus As'ad Pasha al-Azm, housing the Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions.

- Bayt al-Aqqad.

- Maktab Anbar, a mid-19th-century Jewish private mansion, restored by the Ministry of Culture in 1976 to serve as a library, exhibition center, museum and craft workshops.[130]

- Beit al-Mamlouka, a 17th-century Damascene house, serving as a luxury boutique hotel within the old city since 2005.

Threats to the future of the old City

Due to the rapid decline of the population of Old Damascus (between 1995 and 2009 about 30,000 people moved out of the old city for more modern accommodation),[131] a growing number of buildings are being abandoned or are falling into disrepair. In March 2007, the local government announced that it would be demolishing Old City buildings along a 1,400 m (4,600 ft) stretch of rampart walls as part of a redevelopment scheme. These factors resulted in the Old City being placed by the World Monuments Fund on its 2008 Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites in the world.[132][133] It is hoped that its inclusion on the list will draw more public awareness to these significant threats to the future of the historic Old City of Damascus.

State of old Damascus

In spite of the recommendations of the UNESCO World Heritage Center:[134]

- Souq al-Atiq, a protected buffer zone, was destroyed in three days in November 2006;

- King Faysal Street, a traditional hand-craft region in a protected buffer zone near the walls of Old Damascus between the Citadel and Bab Touma, is threatened by a proposed motorway.

- In 2007, the Old City of Damascus and notably the district of Bab Tuma have been recognized by The World Monument Fund as one of the most endangered sites in the world.[135]

In October 2010, Global Heritage Fund named Damascus one of 12 cultural heritage sites most "on the verge" of irreparable loss and destruction.[136]

Education

Damascus is the main center of education in Syria. It is home to Damascus University, which is the oldest and largest university in Syria. After the enactment of legislation allowing private higher institutions, several new universities were established in the city and in the surrounding area, including:

- Syrian Virtual University

- International University for Science and Technology

- Syrian Private University[137]

- Arab International University

- University of Kalamoon

- Yarmouk Private University

- Wadi International University

- Al-Jazeera University[138]

- European University Damascus

The institutes play an important rule in the education, including:

- Higher Institute of Business Administration

- Higher Institute for Applied Science and Technology

- Higher Institute for Dramatic Arts

- National Institute of Administration

In Damascus, Higher education in Syrian Arab Republic started with sustainable development steps through Damascus University. [139]

- Additional:

- Syrian International Academy for Training and Development

Transportation

Damascus is linked with other major cities in Syria via a motorway network. The M5 connects Damascus with Homs, Hama, Aleppo and Turkey in the north and Jordan in the south. The M1 is going from Homs onto Latakia and Tartus. The M4 links the city with Al-Hasakah and Iraq. The M1 highway connects the city to the western Syria and Beirut.

The main airport is Damascus International Airport, approximately 20 km (12 mi) away from the city, with connections to a few Middle Eastern cities. Before the beginning of the Syrian civil war, the airport had connectivity to many Asian, European, African, and, South American cities. Streets in Damascus are often narrow, especially in the older parts of the city, and speed bumps are widely used to limit the speed of vehicles. Many taxi companies operate in Damascus. Fares are regulated by law and taxi drivers are obliged to use a taximeter.

Public transport in Damascus depends extensively on buses and minibuses. There are about one hundred lines that operate inside the city and some of them extend from the city center to nearby suburbs. There is no schedule for the lines, and due to the limited number of official bus stops, buses will usually stop wherever a passenger needs to get on or off. The number of buses serving the same line is relatively high, which minimizes the waiting time. Lines are not numbered, rather they are given captions mostly indicating the two end points and possibly an important station along the line. Between 2019 and 2022, more than 100 modern buses were delivered from China as part of the international agreement. These deliveries strengthened and modernized the public transport of Damascus.[140][141]

Served by Chemins de Fer Syriens, the former main railway station of Damascus was al-Hejaz railway station, about 1 km (5⁄8 mi) west of the old city. The station is now defunct and the tracks have been removed, but there still is a ticket counter and a shuttle to Damacus Qadam station in the south of the city, which now functions as the main railway station.

In 2008, the government announced a plan to construct a Damascus Metro.[142] The green line will be an essential west–east axis for the future public transportation network, serving Moadamiyeh, Sumariyeh, Mezzeh, Damascus University, Hijaz, the Old City, Abbassiyeen and Qaboun Pullman bus station. A four-line metro network is expected be in operation by 2050.

Culture

Damascus was chosen as the 2008 Arab Capital of Culture.[143] The preparation for the festivity began in February 2007 with the establishing of the Administrative Committee for "Damascus Arab Capital of Culture" by a presidential decree.[144]

Museums

- National Museum of Damascus

- Azem Palace

- Military Museum

- October War Panorama Museum

- Museum of Arabic Calligraphy

- Nur al-Din Bimaristan

Sports and leisure

Popular sports include football, basketball, swimming, tennis, table tennis, equestrian and chess. Damascus is home to many football clubs that participate in the Syrian Premier League including al-Jaish, al-Shorta, Al-Wahda and Al-Majd. Many Other sport clubs are located in several districts of the city: Barada SC, Al-Nidal SC, Al-Muhafaza, Qasioun SC, al-Thawra SC, Maysalun SC, al-Fayhaa SC, Dummar SC, al-Majd SC and al-Arin SC.

The fifth and the seventh Pan Arab Games were held in Damascus in 1976 and 1992 respectively.

The now modernized Al-Fayhaa Sports City features a basketball court and a hall that can accommodate up to 8,000 people. In late November 2021, Syria's national basketball team played there against Kazakhstan, making Damascus host of Syria's first international basketball tournament in almost two decades.[145]

The city also has a modern golf course located near the Ebla Cham Palace Hotel at the southeastern outskirts of Damascus.

Damascus has busy nightlife. Coffeehouses offer Arabic coffee, tea and nargileh (water pipes). Card games, tables (backgammon variants), and chess are activities frequented in cafés.[146] These coffeehouses have had in the past an international reputation, as indicated by Letitia Elizabeth Landon's poetical illustration, Cafes in Damascus, to a picture by William Henry Bartlett in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1837.[147] Current movies can be seen at Cinema City which was previously known as Cinema Dimashq.

Tishreen Park is one of the largest parks in Damascus. It is home to the annual Damascus Flower Show. Other parks include: al-Jahiz, al-Sibbki, al-Tijara, al-Wahda, etc.. The city's famous Ghouta oasis is also a weekend-destination for recreation. Many recreation centers operate in the city including sport clubs, swimming pools and golf courses. The Syrian Arab Horse Association in Damascus offers a wide range of activities and services for horse breeders and riders.[148]

Nearby attractions

- Madaya: a small mountainous town well known holiday resort.

- Bloudan: a town located 51 km (32 mi) north-west of the Damascus, its moderate temperature and low humidity in summer attracts many visitors from Damascus and throughout Syria, Lebanon and the Persian Gulf.

- Zabadani: a city in close to the border with Lebanon. Its mild weather along with the scenic views, made the town a popular resort both for tourists and for visitors from other Syrian cities.

- Maaloula: a town dominated by speakers of Western Neo-Aramaic.

- Saidnaya: a city located in the mountains, 1,500 metres (4,921 ft) above sea level, it was one of the episcopal cities of the ancient Patriarchate of Antioch.

Twin towns – sister cities

Notable people from Damascus

Notes

- Al-Fayhaa (Arabic: الْفَيْحَاء), is an adjective which means "spacious".[3]

- Historically, Baalshamin (Imperial Aramaic: ܒܥܠ ܫܡܝܢ, romanized: Ba'al Šamem, lit. 'Lord of Heaven(s)'),[19][20] was a Semitic sky-god in Canaan/Phoenicia and ancient Palmyra.[21][22] Hence, Sham refers to (heaven or sky).

References

- "Biggest Cities In Syria". 25 April 2017. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- "Damascus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Almaany Team. "معنى كلمة الفَيْحَاءُ في معجم المعاني الجامع والمعجم الوسيط – معجم عربي عربي – صفحة 1". almaany.com. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- "President al-Assad issues decrees on appointing new governors for eight Syrian provinces". SANA. 20 July 2022. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Albaath.news statement by the governor of Damascus, Syria Archived 16 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Arabic), April 2010

- "Damascus population 2022". World Population Review. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- Sub-national HDI. "Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org.

- Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). "Damascus". In Janet L. Abu-Lughod (ed.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 119–126. ISBN 978-1-5760-7919-5. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- Sarah Birke (2 August 2013), Damascus: What's Left, New York Review of Books, archived from the original on 4 December 2018, retrieved 12 May 2021

- Totah, Faedah M. (2009). "Return to the origin: negotiating the modern and unmodern in the old city of Damascus". City & Society. 21 (1): 58–81. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01015.x.

- Bowker, John (1 January 2003), "Damascus", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780192800947.013.1793 (inactive 1 August 2023), ISBN 978-0-19-280094-7, archived from the original on 7 April 2022, retrieved 15 January 2021

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Buckley, Julia (4 September 2019). "World's most livable city revealed". CNN Travel. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Gauthier, Henri (1929). Dictionnaire des Noms Géographiques Contenus dans les Textes Hiéroglyphiques Vol. 6. p. 42.

- List I, 13 in J. Simons, Handbook for the Study of Egyptian Topographical Lists relating to Western Asia Archived 26 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Leiden 1937. See also Y. AHARONI, The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography, London 1967, p147, No. 13.

- Paul E. Dion (May 1988). "Ancient Damascus: A Historical Study of the Syrian City-State from Earliest Times Until Its Fall to the Assyrians in 732 BC., Wayne T. Pitard". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (270): 98. JSTOR 1357008.

- Frank Moore Cross (February 1972). "The Stele Dedicated to Melcarth by Ben-Hadad of Damascus". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (205): 40. doi:10.2307/1356214. JSTOR 1356214. S2CID 163497507.

- Miller, Catherine; Al-Wer, Enam; Caubet, Dominique; Watson, Janet C.E. (2007). Arabic in the City: Issues in Dialect Contact and Language Variation. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 978-1135978761.

- "Kalmasoft - Phonetic Database of Syriac Words". www.kalmasoft.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- Teixidor, Javier (2015). The Pagan God: Popular Religion in the Greco-Roman Near East. Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781400871391. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides. p. 290. ISBN 9781858287188. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Dirven, Lucinda (1999). The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria. BRILL. p. 76. ISBN 978-90-04-11589-7. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- J.F. Healey (2001). The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. BRILL. p. 126. ISBN 9789004301481. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edomond (1997). "AL-SHĀM". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 9. p. 261.

- Younger, K. Lawson Jr. (7 October 2016). A Political History of the Arameans: From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities (Archaeology and Biblical Studies). Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 551. ISBN 978-1589831285.

- romeartlover, "Damascus: the ancient town" Archived 8 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "DMA-UPD Discussion Paper Series No.2" (PDF). Damascus Metropolitan Area Urban Planning and Development. October 2009. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2012.

- The Palestinian refugees in Syria. Their past, present and future. Dr. Hamad Said al-Mawed, 1999

- M. Kottek; J. Grieser; C. Beck; B. Rudolf; F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Tyson, Patrick J. (2010). "SUNSHINE GUIDE TO THE DAMASCUS AREA, SYRIA" (PDF). climates.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- "Damascus INTL Climate Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Moore, A.M.T. The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford, UK: Oxford University, 1978. 192–198. Print.

- Burns 2005, p. 2

- Burns 2005, pp. 5–6

- Burns 2005, p. 7

- "Genesis 14:15 (New International Version)". Bible Gateway. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The Antiquities of the Jews, by Flavius Josephus, Book 1, Ch. 6, Sect. 4". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "The Antiquities of the Jews, by Flavius Josephus, Book 1, Ch. 7, Sect. 2". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "Damascus, Syria : Image of the Day". nasa.gov. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 11 May 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- Burns 2005, p. 9

- Burns 2005, p. 10

- Burns 2005, pp. 13–14

- Burns 2005, p. 11

- "Yale ORACC". Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Burns 2005, pp. 21–23

- Cohen raises doubts about this claim in Cohen, Getzel M; EBSCOhost (2006), The Hellenistic settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa, University of California Press, archived from the original on 27 May 2014, retrieved 26 May 2014 page 137 note 4 - suggeasting the received tradition of the renaming rests on a few writers following Mionnets writings in 1811

- Warwick Ball (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. p. 181. ISBN 9781134823871. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Skolnik, Fred; Michael Berenbaum ( 2007) Encyclopaedia Judaica Volume 5 Granite Hill Publishers pg 527

- Knoblet, Jerry (2005) Herod the Great University Press of America.

- Burns, Ross (2007) Damascus: A History Routledge pg 52

- Riesner, Rainer (1998) Paul's Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing pg 73–89

- Hengel, Martin (1997) Paul Between Damascus and Antioch: The Unknown Years Westminster John Knox Press pg 130

- Riesner, Rainer (1998) Paul's Early Period: Chronology, Mission Strategy, Theology Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing pg 83–84, 89

- Abdulkarim 2003, pp. 35–37.

- Butcher, Kevin (2004). Coinage in Roman Syria: Northern Syria, 64 BC-AD 253. Royal Numismatic Society. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-901405-58-6. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Barclay Vincent Head (1887). "VII. Coele-Syria". Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics. p. 662. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Kaegi 2003, pp. 75–77.

- Crawford 2013, pp. 42–43.

- Safiur-Rahman Mubarakpuri, The Sealed Nectar Archived 12 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, p. 227

- Akbar Shāh Ḵẖān Najībābādī, History of Islam, Volume 1 Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 194. Quote: "Again, the Holy Prophet "P sent Dihyah bin Khalifa Kalbi to the Byzantine king Heraclius, Hatib bin Abi Baltaeh to the king of Egypt and Alexandria; Allabn Al-Hazermi to Munzer bin Sawa the king of Bahrain; Amer bin Aas to the king of Oman. Salit bin Amri to Hozah bin Ali— the king of Yamama; Shiya bin Wahab to Haris bin Ghasanni to the king of Damascus"

- Burns 2005, pp. 98–99

- Burns 2005, p. 100

- Burns 2005, pp. 103–104

- Burns 2005, p. 105

- Burns 2005, pp. 106–107

- Burns 2005, p. 110

- Burns 2005, p. 113

- Burns 2005, pp. 121–122

- Burns 2005, pp. 130–132

- Burns 2005, pp. 135–136

- Burns 2005, pp. 137–138

- Burns 2005, p. 139

- Burns 2005, p. 142

- Burns 2005, p. 147

- "Madrasa Nuriya al-Kubra". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Madrasa al-Nuriyya al-Kubra (Damascus)". Archnet. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Burns 2005, pp. 148–149

- Burns 2005, p. 151

- Phillips, Jonathan (2007). The Second Crusade: Extending the Frontiers of Christendom. Yale University Press. pp. 216–227.

- Hans E. Mayer, The Crusades (Oxford University Press, 1965, trans. John Gillingham, 1972), pp. 118–120.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Penguin. p. 350.

- Hamilton, Bernard (2000). The Leper King and his Heirs: Baldwin IV and the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–136.

- "The Third Crusade: Richard the Lionhearted and Philip Augustus", in A History of the Crusades, vol. II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311, ed. R. L. Wolff and H. W. Hazard (Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1969), pp. 45–49.

- Wolff and Hazard, pp. 67–85.

- R. Stephen Humphreys, From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260 (State University of New York Press, 1977), passim.

- Kenneth M. Setton, Robert Lee Wolff, Harry W. Hazard (editors), A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189-1311, p. 695 Archived 2 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine, University of Wisconsin Press, series "History of the Crusades", 2006

- Johnston, Ruth A. (31 August 2011). All Things Medieval: An Encyclopedia of the Medieval World. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313364624. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Runciman 1987, p. 307.

- Runciman 1987, p. 439.

- Demurger 2007, p. 146.

- Amitai 1987, p. 247.

- Schein 1979, p. 810.

- Amitai 1987, p. 248.

- Nicolle 2001, p. 80.

- "Islamic city Archived 26 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Ibn Khaldun 1952, p. 97.

- "Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century"

- Abd al-Qadir al-Rihawi; Émilie E. Ouéchek (1975). "Les deux takiyya de Damas". Bulletin d'études orientales. Vol. 28. Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. pp. 217–225. JSTOR 41604595. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- Ellen Clare Miller, 'Eastern Sketches – notes of scenery, schools and tent life in Syria and Palestine'. Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Company. 1871. page 90. quoting Eli Jones, a Quaker from New England.

- Twain 1869, p. 283

- Abdel-Raouf Sinno (1998). "The Emperor's visit to the East: As reflected in contemporary Arabic journalism" (PDF). pp. 14–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- Barker, A. (1998) "The Allies Enter Damascus", History Today, Volume 48

- Roberts, P.M., World War I, a Student Encyclopedia, 2006, ABC-CLIO, p. 657

- "Public transportation in Damascus is having an uphill go of it". Archived from the original on 21 March 2012.

- "Heavy gunfire in Syria's capital during the weekend". Haaretz. 10 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Aboufadel, Leith (20 May 2018). "Syrian military in full control of Damascus for first time in years". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 20 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "Least habitable city". Guinness World Records. September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "Revealed: The world's best (and worst) cities to live in". The Telegraph. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- "The world's least liveable cities are starting to improve". The Economist. 31 July 2023.

- "Damascus International Fair". Archived from the original on 12 November 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Cummins, Chip. "Damascus Revels in Its New Allure to Investors". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2009.