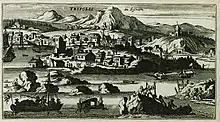

Tripoli, Lebanon

Tripoli (Arabic: طرابلس, ALA-LC: Ṭarābulus;[lower-alpha 1] Lebanese Arabic: Ṭrablus) is the largest city in northern Lebanon and the second-largest city in the country. Situated 81 km (50 mi) north of the capital Beirut, it is the capital of the North Governorate and the Tripoli District. Tripoli overlooks the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and it is the northernmost seaport in Lebanon. It holds a string of four small islands offshore. The Palm Islands were declared a protected area because of their status of haven for endangered loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta), rare monk seals and migratory birds. Tripoli borders the city of El Mina, the port of the Tripoli District, which it is geographically conjoined with to form the greater Tripoli conurbation.

Tripoli

طرابلس | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles, Mansouri Great Mosque minaret, Mamluk architecture, bay view, and a Syriac Catholic church | |

| Nickname(s): The City of Knowledge and Scholars | |

Tripoli | |

| Coordinates: 34°26′12″N 35°50′04″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | North Governorate |

| District | Tripoli District |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ahmed Qamar Al-Din |

| Area | |

| • Total | 27.3 km2 (10.5 sq mi) |

| Population (January 2019) | |

| • Total | 243,800 |

| Time zone | +2 |

| • Summer (DST) | +3 |

| Area code | 06 |

| Website | tripoli-lebanon.org |

The history of Tripoli dates back at least to the 14th century BCE. The city is well known for containing the Mansouri Great Mosque and the largest Crusader fortress in Lebanon, the Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles. It has the second highest concentration of Mamluk architecture after Cairo.

In the Arab World, Tripoli is sometimes known as Ṭarābulus al-Sham (Arabic: طرابلس الشام), or Levantine Tripoli, to distinguish it from its Libyan counterpart, known as Tripoli-of-the-West (Arabic: طرابلس الغرب; Ṭarābulus al-Gharb).

With the formation of Lebanon and the 1948 breakup of the Syrian–Lebanese customs union, Tripoli, once on par in economic and commercial importance to Beirut, was cut off from its traditional trade relations with the Syrian hinterland and therefore declined in relative prosperity.[2]

Names

According to classical writers Diodorus Siculus, Pliny the Elder, and Strabo, the city was founded by combining colonies from three different Phoenician cities - Tyre, Sidon and Arwad. These colonies were each a stadion (c. 180 m) apart from each other, and the combined city became known as "Triple City", or Tripolis in Greek.[3]

Tripoli had a number of different names as far back as the Phoenician age. In the Amarna letters the name "Derbly", possibly a Semitic cognate of the city's modern Arabic name Ṭarābulus, was mentioned, and in other places "Ahlia" or "Wahlia" are mentioned (14th century BCE).[4] In an engraving concerning the invasion of Tripoli by the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (888–859 BCE), it is called Mahallata or Mahlata, Mayza, and Kayza.[5]

Under the Phoenicians, the name Athar was used to refer to Tripoli.[6] When the Ancient Greeks settled in the city they called it Τρίπολις (Tripolis), meaning "three cities," influenced by the earlier phonetically similar but etymologically unrelated name Derbly.[7] The Arabs called it Ṭarābulus and Ṭarābulus al-Šām (referring to bilād al-Šām, to distinguish it from the Libyan city with the same name).

Once, Tripoli was also known as al-fayḥā′ (الفيحاء), which is a term derived from the Arabic verb faha which is used to indicate the diffusion of a scent or smell. Tripoli was once known for its vast orange orchards. During the season of blooming, the pollen of orange flowers was said to be carried on the air, creating a splendid perfume which filled the city and suburbs.[8]

The city of Tripoli is also given the title of "The City of Knowledge and Scholars" (from Arabic: طرابلس مدينة العلم والعلماء, romanized: Tarābulus madīnat al-'ilm wal-'ulamā'.)[9][10][11][12]

History

Evidence of settlement in Tripoli dates back as early as 1400 BCE. In the 9th century, the Phoenicians established a trading station in Tripoli and later, under Persian rule, the city became the center of a confederation of the Phoenician city-states of Sidon, Tyre, and Arados Island. Under Hellenistic rule, Tripoli was used as a naval shipyard and the city enjoyed a period of autonomy. It came under Roman rule around 64 BCE. The 551 Beirut earthquake and tsunami destroyed the Byzantine city of Tripoli along with other Mediterranean coastal cities.

During Umayyad rule, Tripoli became a commercial and shipbuilding center. It achieved semi-independence under Fatimid rule, when it developed into a center of learning. The Crusaders laid siege to the city at the beginning of the 12th century and were able finally to enter it in 1109. This caused extensive destruction, including the burning of Tripoli's famous library, Dar al-'Ilm (House of Knowledge), with its thousands of volumes. During the Crusaders' rule the city became the capital of the County of Tripoli. In 1289, it fell to the Mamluks and the old port part of the city was destroyed. A new inland city was then built near the old castle. During Ottoman rule from 1516 to 1918, it retained its prosperity and commercial importance. Tripoli and all of Lebanon was under French mandate from 1920 until 1943 when Lebanon achieved independence.

Ancient period

Many historians reject the presence of any Phoenician civilization in Tripoli before the 8th (or sometimes 4th) century BCE. Others argue that the north–south gradient of Phoenician port establishments on the Lebanese coast indicates an earlier age for the Phoenician Tripoli.

Tripoli has not been extensively excavated because the ancient site lies buried beneath the modern city of El Mina. However, a few accidental finds are now in museums. Excavations in El Mina revealed skeletal remains of ancient wolves, eels, and gazelles, part of the ancient southern port quay, grinding mills, different types of columns, wheels, Bows, and a necropolis from the end of the Hellenistic period. A sounding made in the Crusader castle uncovered Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, in addition to Roman, Byzantine, and Fatimid remains. At the Abou Halka area (at the southern entrance of Tripoli) refuges dating to the early (30,000 years old) and middle Stone Age were uncovered.[13]

Tripoli became a financial center and main port of northern Phoenicia with sea trade (East Mediterranean and the West), and caravan trade (North Syria and hinterland).

Under the Seleucids, Tripoli gained the right to mint its own coins (112 BCE); it was granted autonomy between 104 and 105, which it retained until 64 BCE. At the time, Tripoli was a center of shipbuilding and cedar timber trade (like other Phoenician cities).

During the Roman and Byzantine period, Tripoli witnessed the construction of important public buildings including municipal stadium or gymnasium due to strategic position of the city midway on the imperial coastal highway leading from Antioch to Ptolemais. In addition, Tripoli retained the same configuration of three distinct and administratively independent quarters (Aradians, Sidonians, and Tyrians). The territory outside the city was divided between the three quarters.

Umayyad, Abbasid and Fatimid periods

Tripoli gained in importance as a trading centre for the whole Mediterranean after it was inhabited by the Arabs. Tripoli was the port city of Damascus; the second military port of the Arab Navy, following Alexandria; a prosperous commercial and shipbuilding center; a wealthy principality under the Kutama Ismaili Shia Banu Ammar emirs.[14] Legally, Tripoli was part of the jurisdiction of the military province of Damascus (Jund Dimashq).[15]

The Jewish community of Tripoli traces its roots back to the seventh century, as recounted by the Abbasid-era historian al-Baladhuri. During the caliphate of Rashidun caliph Uthman (644–655), the governor of Syria, Mu'awiya, settled Jews in Tripoli, fostering amicable relations with the majority Sunni Muslims. However, during the persecution of dhimmis by the Shi'ite Fatimid caliph al-Hakim (996–1021), the synagogue faced conversion into a mosque. Notably, during the Seljuk invasion in the 1070s, Tripoli served as a refuge for Jews from Palestine, as documented in Cairo Geniza records.[16]

During a visit by the traveler Nasir-i-Khusrau in 1047, he estimated the size of the population in Tripoli to be around 20,000 and the whole population were Shia Muslims.[17] And according to Nasir Khusraw, the Fatimid Sultan raised a mighty army from Tripoli to defend it against Byzantine, Frankish, Andalusian and Moroccan invasions and raids.[17]

Crusader period

The city became the chief town of the County of Tripoli (Latin Crusader state of the Levant) extending from Byblos to Latakia and including the plain of Akkar with the famous Krak des Chevaliers. Tripoli was also the seat of a bishopric. Tripoli was home to a busy port and was a major center of silk weaving, with as many as 4,000 looms. Important products of the time included lemons, oranges, and sugar cane. For 180 years, during the Frankish rule, Occitan was among the languages spoken in Tripoli and neighboring villages.

At that time, Tripoli had a heterogeneous population including Western Europeans, Greeks, Armenians, Maronites, Nestorians, Jews, and Muslims. During the Crusade period, Tripoli witnessed the growth of the inland settlement surrounding the "Pilgrim's Mountain" (the citadel) into a built-up suburb including the main religious monuments of the city such as: The "Church of the Holy Sepulchre of Pilgrim's Mountain" (incorporating the Shiite shrine), the Church of Saint Mary of the Tower, and the Carmelite Church. The state was a major base of operations for the military order of the Knights Hospitaller, who occupied the famous castle Krak Des Chevaliers (today a UNESCO world heritage site). The state ceased to exist in 1289, when it was captured by the Egyptian Mamluk sultan Qalawun.

The mid-twelfth century earthquake led to the death of many Jews in Tripoli, as noted by Jewish explorer Benjamin of Tudela.[18]

Mamluk period

Tripoli was captured by Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun from the Crusaders in 1289. The Mamluks destroyed the old city and built a new city 4 km inland from it.[20] About 35 monuments from the Mamluk city have survived to the present day, including mosques, madrasas, khanqahs, hammams (bathhouses), and caravanserais, many of them built by local Mamluk amirs (princes).[21] The Mamluks did not fortify the city with walls but restored and reused the Crusader Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles on site.[20]

During the Mamluk period, Tripoli became a central city and provincial capital of the six kingdoms in Mamluk Syria. Tripoli ranked third after Aleppo and Damascus. The kingdom was subdivided into six wilayahs or provinces and extended from Byblos and Aqra mountains south, to Latakia and al Alawiyyin mountains north. It also included Hermel, the plain of Akkar, and Hosn al-Akrad (Krak des Chevaliers).[22]

Tripoli became a major trading port of Syria supplying Europe with candy, loaf and powdered sugar (especially during the latter part of the 14th century). The main products from agriculture and small industry included citrus fruits, olive oil, soap, and textiles (cotton and silk, especially velvet).

The Mamluks formed the ruling class holding main political, military and administrative functions. Arabs formed the population base (religious, industrial, and commercial functions) and the general population included the original inhabitants of the city, immigrants from different parts of the Levant, North Africans who accompanied Qalawun's army during the liberation of Tripoli, Eastern Orthodox Christians, some Western families, and a minority of Jews. The population size of Mamluk Tripoli is estimated at 20,000–40,000; against 100,000 in each of Damascus and Aleppo.[22]

Mamluk Tripoli witnessed a high rate of urban growth and a fast city development (according to traveler's accounts). It also had poles of growth including the fortress, the Great Mosque, and the river banks. The city had seven guard towers on the harbor site to defend the inland city, including what still stands today as the Lion Tower. During the period the castle of Saint Gilles was expanded as the Citadel of Mamluk Tripoli. The "Aqueduct of the Prince" was reused to bring water from the Rash'in spring. Several bridges were constructed and the surrounding orchards expanded through marsh drainage. Fresh water was supplied to houses from their roofs.

The urban form of Mamluk Tripoli was dictated mainly by climate, site configuration, defense, and urban aesthetics. The layout of major thoroughfares was set according to prevailing winds and topography. The city had no fortifications, but heavy building construction characterized by compact urban forms, narrow and winding streets for difficult city penetration. Residential areas were bridged over streets at strategic points for surveillance and defense. The city also included many loopholes and narrow slits at street junctions.

The religious and secular buildings of Mamluk Tripoli comprise a fine example of the architecture of that time. The oldest among them were built with stones taken from 12th and 13th-century churches; the characteristics of the architecture of the period are best seen in the mosques and madrassas, the Islamic schools. It is the madrassas which most attract attention, for they include highly original structures as well as decoration: here a honeycombed ceiling, there a curiously shaped corniche, doorway or moulded window frame. Among the finest is the madrassa al-Burtasiyah, with an elegant façade picked out in black and white stones and a highly decorated lintel over the main door.

Public buildings in Mamluk Tripoli were emphasized through sitting, façade treatment, and street alignment. Well-cut and well-dressed stones (local sandstone) were used as media of construction and for decorative effects on elevations and around openings (the ablaq technique of alternating light and dark stone courses). Bearing walls were used as vertical supports. Cross vaults covered most spaces from prayer halls to closed rectangular rooms, to galleries around courtyards. Domes were constructed over conspicuous and important spaces like tomb chambers, mihrab, and covered courtyards. Typical construction details in Mamluk Tripoli included cross vaults with concave grooves meeting in octagonal openings or concave rosettes as well as simple cupolas or ribbed domes. The use of double drums and corner squinches was commonly used to make the transition from square rooms to round domes.[13]

Decorations in Mamluk buildings concentrated on the most conspicuous areas of buildings: minarets, portals, windows, on the outside, and mihrab, qiblah wall, and floor on the inside. Decorations at the time may be subdivided into structural decoration (found outside the buildings and incorporate the medium of construction itself such as ablaq walls, plain or zigzag moldings, fish scale motifs, joggled lintels or voussoirs, inscriptions, and muqarnas) and applied decoration (found inside the buildings and include the use of marble marquetry, stucco, and glass mosaic).[13]

Mosques evenly spread with major concentration of madrasas around the Mansouri Great Mosque. All khans were located in the northern part of the city for easy accessibility from roads to Syria. Hammams (public baths) were carefully located to serve major population concentrations: one next to the Grand Mosque, the other in the center of the commercial district, and the third in the right-bank settlement.

About 35 monuments from the Mamluk city have survived to the present day, including mosques, madrasas, khanqahs, hammams, and caravanserais, many of them built by local Mamluk amirs.[21] Major buildings in Mamluk Tripoli included six congregational mosques (the Mansouri Great Mosque, al-Aattar, Taynal, al-Uwaysiyat, al-Burtasi, and al-Tawbat Mosques). Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil (r. 1290–93) founded the city's first congregational mosque in memory of his father (Qalawun), in either late 1293 or 1294 (693 AH).[23][24] Six madrasas were later built around the mosque.[24][25][26] The Mamluks did not fortify the city with walls but restored and reused a Crusader citadel on the site.[20] In addition, there were two quarter mosques (Abd al-Wahed and Arghoun Shah), and two mosques that were built on empty land (al-Burtasi and al-Uwaysiyat). Other mosques incorporated earlier structures (churches, khans, and shops). Mamluk Tripoli also included 16 madrasas of which four no longer exist (al-Zurayqiyat, al-Aattar, al-Rifaiyah, and al-Umariyat). Six of the madrasas concentrated around the Grand Mosque. Tripoli also included a Khanqah, many secular buildings, five Khans, three hammams (Turkish baths) that are noted for their cupolas. Hammams were luxuriously decorated and the light streaming down from their domes enhances the inner atmosphere of the place.

Ottoman period

During the Ottoman period, Tripoli became the provincial capital and chief town of the Eyalet of Tripoli, encompassing the coastal territory from Byblos to Tarsus and the inland Syrian towns of Homs and Hama; the two other eyalets were Aleppo Eyalet, and Şam Eyalet. Until 1612, Tripoli was considered as the port of Aleppo. It also depended on Syrian interior trade and tax collection from mountainous hinterland. Tripoli witnessed a strong presence of French merchants during the 17th and 18th centuries and became under intense inter-European competition for trade. Tripoli was reduced to a sanjak centre in the Vilayet of Beirut in 19th century and retained her status until 1918 when it was captured by British forces.

Public works in Ottoman Tripoli included the restoration of the Citadel of Tripoli by Suleiman I, the Magnificent. That was the only major project during 400 years of Ottoman Rule. Later governors brought further modifications to the original Crusader structure used as garrison center and prison. Khan al-Saboun (originally a military barrack) was constructed in the center of the city to control any uprising. Ottoman Tripoli also witnessed the development of the southern entrance of the city and many buildings, such as the al-Muallaq or "hanging" Mosque (1559), al-Tahhan Mosque (early 17th century), and al-Tawbah mosque (Mamluk construction, destroyed by 1612 flood and restored during early Ottoman Period). It also included several secular buildings, such as Khan al-Saboun (early 17th century) and Hammam al-Jadid (1740).

Independent Lebanon

Since the end of Ottoman rule in 1918, Tripoli has been mired in a period of extended economic and political decline. Beirut's rise as Lebanon's dominant port deprived Tripoli of its former preeminence as a trade hub, and globalization eroded the city's ability to compete in manufacturing.[27] Lebanon's civil war, from 1975 to 1990, hit Tripoli hard. On 15 September 1985 intense fighting broke out between Tawheed al-Islami, a Sunni militia which controlled the harbour and was backed by the PLO, and the Alawite Arab Democratic Party’s militia. The ADP were backed by the communist Red Knights as well as Syrian special forces. After a week of fighting which saw around 150 killed, 4500 wounded and 200,000 people leaving their homes, the Syrians brokered a truce which involved the Syrian army occupying five key positions and the removal of heavy weapons.[28] The truce broke down on 27 September and Tahweed al-Islami positions where bombarded from SSNP and Syrian artillery positions in the surrounding hills. On 1 October, following an Iranian diplomatic intervention, Tahweed agreed to surrender their heavy weapons and Syrian troops, on 6 October, were deployed throughout the city. A further 350 people had been killed and hundreds more wounded.[29]

The Syrian army remained in the city for almost three decades until 2005:

As a majority Sunni city with a growing strain of indigenous Islamist militancy, Tripoli suffered some of the Syrians’ cruelest predations at a time when then-President Hafez al-Assad was engaged in the brutal suppression of Syria’s own Muslim Brotherhood.[27]

Wartime violence and instability triggered waves of emigration and capital flight. It also left Tripoli increasingly isolated, not least due to the dismantling of Lebanon's rail network and the abandonment of the Tripoli railway station. The city, moreover, saw little of the post-war reconstruction funding that Prime Minister Rafic Hariri ushered into Lebanon, with an overwhelming focus on the capital.[27]

In the years since, living conditions in Tripoli have continued to decline. In 2016, the United Nation's Human Settlements Program estimated that 58% of Tripoli's Lebanese residents lived in poverty.[30] That already high figure preceded Lebanon's 2019 financial crisis, which has ratcheted up poverty and food insecurity.[31]

Tripoli's stagnation is attributable, in part, to the city's dysfunctional politics, in which a fragmented array of Sunni political figures (such as Saad Hariri, Najib Mikati, Faisal Karami, and Ashraf Rifi) vie for influence through competing networks of patronage: "No single leader has been able to assert dominance, leaving city politics to devolve into chaos."[32]

Demographics

Tripoli has a majority Sunni Muslim population. Lebanon's small Alawite community is concentrated in the Jabal Mohsen neighborhood. Christians constitute today less than 5 percent of the population of the city.[2][33]

Geography

Climate

Tripoli has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa) with mild wet winters and very dry, hot summers. Temperatures are moderated throughout the year due to the warm Mediterranean current coming from Western Europe. Therefore, temperatures are warmer in the winter by around 10 °C (18 °F) and cooler in the summer by around 7 °C (13 °F) compared to the interior of Lebanon. Although snow is an extremely rare event that only occurs around once every ten years, hail is common and occurs fairly regularly in the winter. Rainfall is concentrated in the winter months, with the summer typically being very dry.

| Climate data for Tripoli, Lebanon | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.3 (86.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

27.2 (81.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.8 (74.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

26.6 (79.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.8 (67.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 183 (7.2) |

131 (5.2) |

110 (4.3) |

49 (1.9) |

17 (0.7) |

2 (0.1) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

9 (0.4) |

57 (2.2) |

112 (4.4) |

176 (6.9) |

848 (33.3) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[34] | |||||||||||||

Offshore islands

Tripoli has many offshore islands. The Palm Islands Nature Reserve, or the Rabbits' Island, is the largest of the islands with an area of 20 ha (49 acres). The name "Araneb" or Rabbits comes from the great numbers of rabbits that were grown on the island during the time of the French mandate early in the 20th century. It is now a nature reserve for green turtles, rare birds and rabbits. Declared as a protected area by UNESCO in 1992, camping, fire building or other depredation is forbidden. In addition to its scenic landscape, the Palm Island is also a cultural heritage site. Evidence for human occupation, dated back to the Crusader period, was uncovered during 1973 excavations by the General Directorate of Antiquities. The Bakar Islands, also known as Abdulwahab Island, were leased to Adel and Khiereddine Abdulwahab as a shipyard, since the Ottoman rule and until this day a well known ship and marine contractor. It was also known as St Thomas Island during the Crusades. It is the closest to the shore and can be accessed via a bridge that was built in 1998. Bellan Island's name comes from a plant found on the island and used to make brooms. Some people claim that the name comes from the word "blue whale" (Baleine in French) that appeared next to the island in early 20th century. Fanar Island is 1,600 m (5,200 ft) long and is the home of a light-house built during the 1960s.

The opposite of Palms Island, which is a large flat sandy beach, is Ramkin Island. This island is largely made up of cliffs and rocks. Anyone who enjoys adventure, cliff leaping, free diving, spear fishing, and snorkeling will enjoy this location.

Architecture

Citadel of Raymond de Saint-Gilles

The citadel takes its name from Raymond de Saint-Gilles, who dominated the city in 1102 and commanded a fortress to be built in which he named Mont Pelerin (Mt Pilgrim). The original castle was burnt down in 1289, and rebuilt again on numerous occasions and was rebuilt in 1307–08 by Emir Essendemir Kurgi.

Later the citadel was rebuilt in part by the Ottoman Empire which can be seen today, with its massive Ottoman gateway, over which is an engraving from Süleyman the Magnificent who had ordered the restoration. In the early 19th century, the Citadel was extensively restored by the Ottoman Governor of Tripoli Mustafa Agha Barbar.

The Clock Tower

The Clock tower is one of the most iconic monuments in Tripoli. The tower is located in Al-Tell square, and was gifted to the city by the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[27] It was erected in 1906 to celebrate the 30th year of Abdulhamid II of the Ottoman Empire, like the Jaffa Clock Tower in Israel and many others throughout the Empire.

The Clock tower underwent a complete renovation in 1992 with personal funding from the honorary Turkish consul of Northern Lebanon, Sobhi Akkari, and the second at February 2016 as a gift from the Turkish prime minister in cooperation with the Committee of Antiquities and Heritage in the municipality of Tripoli, and now the clock tower is again operational. "Al Manshieh" which is one of the oldest parks in Tripoli, is located next to the clock tower.

Hammams

When Tripoli was visited by Ibn Batutah in 1355, he described the newly founded Mamluk city. "Traversed by water-channels and full of’ gardens", he writes, "the houses are newly built. The sea lies two leagues distant, and the ruins of the old town are seen on the sea-shore. It was taken by the Franks, but al-Malik ath-Tháhir (Qala’un) retook it from them, and then laid the place in ruins and built the present town. There are fine baths here.’’

Indeed, the hammams built in Tripoli by the early Mamluk governors were splendid edifices and many of them are still present until today. Some of the more known are:

- Abed

- Izz El-Din

- Hajeb

- Jadid

- An-Nouri, built 1333 by the Mamluk governor Nur El-Din, is located in the vicinity of the Grand Mosque.[35]

Oscar Niemeyer's Rachid Karame Fairground

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The helicopter landing apron (left) and the gateway arch to the open-air theatre at the Rashid Karami International Fair | |

| Location | Lebanon |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 1702 |

| Inscription | 2022 (45th Session) |

| Endangered | 2022-present |

The International Fair of Tripoli site,[36] formally known as the Rachid Karami International Exhibition Center, is a complex of buildings designed by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer who was commissioned for the project in 1962. The site was built for a World's Fair event to be held in the city, but construction was halted in 1975 due to the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war, and never resumed. The site contains 15 semi-completed Niemeyer buildings within an approximate 75.6 ha (187-acre) area near Tripoli's southern entrance.[37]

"More recent years have seen the fairground undermined by a mixture of periodic instability and nonsensical administrative procedures that make it virtually impossible to put the facility to use. If the city needed any more physical metaphors for decay, the fairground is flanked by a Quality Inn that is literally falling apart, and whose ownership is years overdue on payment to the site’s administrators."[27]

In 2023, the Rashid Karami International Fair was added to both the World Heritage List and the List of World Heritage in Danger.[38]

Tripoli Railway Station

Churches

Many churches in Tripoli are a reminder of the history of the city. These churches also show the diversity of Christians in Lebanon and particularly in Tripoli:

- Beshara Catholic Church

- Armenian Evangelical Baptist Church

- Latin Church (Roman Catholic)

- Moutran Church

- Armenian Orthodox Church

- Greek Catholic Church

- St Efram Syriac Orthodox Church

- St. Elie Orthodox Church

- St. John of the Pilgrims Mount church

- St. Jorjios (George) Catholic Church

Mosques

Tripoli is a very rich city containing many mosques that are spread all over the city. In every district of the city there is a mosque. During the Mamluk era, a lot of mosques were built and many still remain until today.

Some of the more known mosques:

- Al-Attar Mosque

- Abou Bakr Al Siddeeq

- Arghoun Shah

- Al-Burtasi Mosque

- Kabir al Aali

- Mahmoud Beik the Sanjak

- Mansouri Great Mosque

- Omar Ibn El-Khattab Mosque

- Sidi Abdel Wahed

- Tawbah Mosque

- Tawjih Mosque

- Taynal Mosque

- Al Bachir Mosque

- Hamza Mosque

- Al Rahma Mosque

- Al Salam Mosque

- Al-Uwaysiyat Mosque

- Mu'allaq Mosque

The Al-Ghuraba cemetery is located within the city.

Education

Tripoli has a large number of schools of all levels, public and private. It is also served by several universities within the city limits as well as in its metro area.

The universities in Tripoli and its metro area are:

- University of Tripoli Lebanon

- The Lebanese University – North Lebanon Branch

- Universite St Joseph – North Lebanon

- Lebanese International University (Dahr el Ein, Just outside the city)

- Al-Manar University of Tripoli (changed to "City University")

- Jinan University

- University of Balamand (Qelhat, in the Koura district, just outside the city)

- Notre Dame University (Barsa, in the Koura district, just outside the city)

- Arts, Sciences and Technology University in Lebanon-North Lebanon Branch

- Beirut Arab University – North Lebanon Branch

- Universite Saint Espirt de Kaslik – Chekka ( Just Outside The City )

- Université de Technologie et de Sciences Appliquées Libano-Française (chamber of commerce)

- Azm university

Economy

Commerce

Tripoli, while once economically comparable to Beirut, has declined in recent decades.[2] Organizations such as the Business Incubation Association in Tripoli (BIAT) are currently trying to revive traditional export businesses such as furniture production, artisanal copper goods, soaps, as well as expand new industries such as ICT offshoring and new technological invention.[39]

The Tripoli Special Economic Zone (TSEZ) was established in 2008 to provide exemptions from many taxes and duties for investment projects that have more than $300,000 of capital and more than half their workers from Lebanon.[40] It is a 55-hectare site adjacent to the Port of Tripoli.[41]

Recently, a Tripoli development plan called "Tripoli Vision 2020" has been formulated and supported by a number of advisory councils including influential key government officials and prominent businessmen in the city. The goal of the project is to provides a comprehensive framework consisting of promoting investment, investing, training, re-skilling, talent placement and output promotion to reinvigorate the city's economy. The Tripoli Vision 2020 was sponsored by the Prime Minister Saad Hariri Office and the Tripoli MPs Joint Office with the comprehensive study conducted by Samir Chreim of SCAS Inc.[42]

Inequality

Tripoli embodies Lebanon's extreme wealth inequality: Although it is one of the country's most concentrated centers of poverty, it is also the hometown of several extravagantly wealthy politicians, notably including Najib Mikati, Taha Mikati and Mohammad Safadi who are accused of accumulating their wealth by embezzling government funds.[43]

The Soap Khan

The khan, built around a square courtyard decorated with a fountain, houses soap making workshops and shops.

At the end of the 15th century, the governor of Tripoli Yusuf Sayfa Pasha established Khan Al Saboun (the hotel of soap traders). This market was finished at the beginning of the 16th century, the last days of the Mamluk rule. The manufacture of soap was very popular in Tripoli. There, the market became a trade center where soap was produced and sold. Afterwards, traders of Tripoli began to export their soap to Europe.

Initially, perfumed soaps were offered as gifts in Europe and as a result, handiwork developed in Tripoli. Due to the ongoing increase of the demand, craftsmen started to consider soap making as a real profession and real art which led to an increased demand for Tripoli soap in various Arab and Asian countries. Currently, many varieties of soap are manufactured and sold in Tripoli such as anti-acne soaps, moisturizing soaps, slimming soaps, etc. which has increased an exportation of these soap products.

The raw material used for these kinds of soap is olive oil. The Tripoli soap is also composed of: honey, essential oils, and natural aromatic raw materials like flowers, petals, and herbs. The soaps are dried in the sun, in a dry atmosphere, allowing the evaporation of the water that served to mix the different ingredients. The drying operation lasts for almost three months. As the water evaporates, a thin white layer appears on the soap surface, from the soda that comes from the sea salts. The craftsman brushes the soap very carefully with his hand until the powder trace is eliminated.

Khan el-Khayyatin–the Tailors' Khan

Unlike other khans built around a square courtyard, el-Khayyatin, built in the 14th century, is a 60 meter long passage with arches on each side.[44]

Arabic sweets

Tripoli is regionally known for its Arabic sweets where people consider it as one of the main attractions and reasons to visit the city. Some sweetshops have even built a regionally and even internationally recognized brand name like Abdul Rahman & Rafaat Al Hallab, who both became so popular, opening shops outside Tripoli and shipping sweets boxes worldwide.

Environmental issues

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Tripoli is twinned with:

Naples, Italy

Naples, Italy Damascus, Syria

Damascus, Syria Larnaca, Cyprus

Larnaca, Cyprus Faro, Portugal

Faro, Portugal Toulouse, France

Toulouse, France

See also

Notes

- This pronunciation of Tripoli's Arabic name is written down as طَرَابُلُس in vowelized form.[1]

References

- "طَرَابُلُس: Lebanon". Geographical Names. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- http://www.mafhoum.com/press10/312P1.htm

- John Murray (Firm); Porter, J.L. (1868). A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: Including an Account of the Geography, History, Antiquities, and Inhabitants of These Countries, the Peninsula of Sinai, Edom, and the Syrian Desert; with Detailed Descriptions of Jerusalem, Petra, Damascus, and Palmyra. A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: Including an Account of the Geography, History, Antiquities, and Inhabitants of These Countries, the Peninsula of Sinai, Edom, and the Syrian Desert; with Detailed Descriptions of Jerusalem, Petra, Damascus, and Palmyra. p. 549. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

Tripoli, according to ancient writers (Diodorus Siculus, Pliny, and Strabo), originally consisted of three quarters, a stadium distant from each other, and founded respectively by colonies from Aradus, Sidon, and Tyre - hence its name, "the Triple City."

- Les peuples et les civilisations du Proche Orient by Jawād Būlus. p. 308.

- Wanderings −2: History of the Jews by Chaim Potok. p. 169.

- History of Syria, Including Lebanon and Palestine by Philip Khuri Hitti. p. 225.

- Lebanon in Pictures by Peter Roop, Sam Schultz, Margaret J. Goldstein. p. 17.

- Ghazi Omar Tadmouri (30 October 2009). "Names of Tripoli through the history". Tripoli City. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "President's Message - City University". 2021-05-24. Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- admin (2015-03-14). "طرابلس الفيحاء مدينة العلم والعلماء والآثار... تمتاز بقلعتها وحلوياتها". القدس العربي (in Arabic). Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- اللواء, جريدة. "طرابلس، مدينة العلم والعلماء والإنتفاضات والثورات". جريدة اللواء (in Arabic). Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- Abdo, Ibrahim (2022-08-23). "طرابلس، مدينة العلم والعلماء!". SQM Market (in Arabic). Retrieved 2022-11-20.

- Saliba, R., Jeblawi, S., and Ajami, G., Tripoli the Old City: Monument Survey – Mosques and Madrasas; A Sourcebook of Maps and Architectural Drawings, Beirut: American University of Beirut Publications, 1995.

- William Harris (19 Jul 2012). Lebanon: A History, 600–2011 (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9780195181111.

- Tadmouri, O. AS., Lubnan min al-fath al-islami hatta sukut al-dawla al-'umawiyya (13–132 H/ 634–750 CE): Silsilat Dirasat fi Tarih AlSahel AlShami, Tripoli, 1990. Arabic.

- Schulze, Kirsten. "Sidon". In Stillman, Norman A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Reference Online.

- al-Qubadiani, Nasir ibn Khusraw. Safarnama (سفرنامه). p. 48.

- Schulze, Kirsten. "Tripoli, Lebanon". In Stillman, Norman A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Reference Online.

- "Jami' al-Mansuri al-Kabir". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- Luz, Nimrod (2002). "Tripoli Reinvented: A Case of Mamluk Urbanization". In Lev, Yaacov (ed.). Towns and material culture in the medieval Middle East. Brill. pp. 53–71. ISBN 9004125434.

- Bloom & Blair 2009, Tripoli (i)

- Tadmouri, O. AS., Tarikh Tarablus al-siyasi wa'-hadari Aabr al-'usour, Tripoli, 1984. (in Arabic)

- "Jami' al-Mansuri al-Kabir". Archnet. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- Mahamid, Hatim (2009). "Mosques as higher educational institutions in Mamluk Syria". Journal of Islamic Studies. 20 (2): 188–212. doi:10.1093/jis/etp002.

- Mohamad, Danah (2020). Review of the Development and Change of Tripoli Bazaar in Lebanon (PDF). Bursa Uludağ University (Master's thesis). p. 81.

- "Qantara - Madrasa al-Qartâwîyya". www.qantara-med.org. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- Simon, Alex (30 January 2017). "The city that didn't know where to start - Tripoli's revolving stalemate". synaps.network. Retrieved 2021-11-16.

- Middle East International No 259, 27 September 1985, Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters MP; Jim Muir pp.7,8

- Middle East International No 260, 11 October 1985, Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters MP; Jim Muir pp.10,11

- "Tripoli City Profile | UN-Habitat". unhabitat.org. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- Gebeily, Maya. "Portrait of poverty in Lebanon as UN visits poorest place on Med". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- Parreira, Christiana (23 October 2019). "The art of not governing". Synaps.

- Riad Yazbeck. "Return of the Pink Panthers?" Archived 2012-02-19 at the Wayback Machine. Mideast Monitor. Vol. 3, No. 2, August 2008

- "Climate: Tripoli". November 2011.

- "Hammam Al-Nouri". Tripoli-Lebanon.com. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- International Fair of Tripoli

- McManus, Manus (3 November 2016). "International Fair of Tripoli by Oscar Niemeyer". e-architect. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Three sites 'in danger' added to UNESCO World Heritage List". CNN. 25 January 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- "Projects :: BIAT". biatcenter.org.

- "About us". Tripoli Special Economic Zone. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- "Lebanon's former finance minister hails special economic zone achievements". Xinhua Net. 2018-07-05. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018.

- "Robert Fadel – روبير فاضل". www.robertfadel.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

- Cornish, Chloe (2020-10-05). "Billionaires and bankrupts: Lebanon's second city highlights inequality". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- "Tripoli-Lebanon.com Tourism-Khans Page". www.tripoli-lebanon.com.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th–20th century

- Josiah Conder (1830), "(Tripoli)", The Modern Traveller, London: J.Duncan

- Hogarth, David George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 291–292.

- Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Tripoli, in Lebanon". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- "Tripoli". Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila (2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Retrieved 2013-03-15.

- For further readings about the Fairground of Oscar Niemeyer: https://re.public.polimi.it/cris/rp/rp116405

External links

- Official website of Tripoli (in Arabic)

- Tripoli on Twitter

- tripoli-lebanon.org

- Tripoli-Lebanon.com Archived 2009-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Tripoli fortress and Panorama of the city at 360 on May 2012

- "Tripoli". Islamic Cultural Heritage Database. Istanbul: Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-04-15.

- ArchNet.org. "Tripoli". Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2012-10-24.