Santorini

Santorini (Greek: Σαντορίνη, pronounced [sadoˈrini]), officially Thira (Greek: Θήρα Greek pronunciation: [ˈθira]) and Classical Greek Thera (English pronunciation /ˈθɪərə/), is an island in the southern Aegean Sea, about 200 km (120 mi) southeast from the Greek mainland. It is the largest island of a small circular archipelago, which bears the same name and is the remnant of a caldera. It forms the southernmost member of the Cyclades group of islands, with an area of approximately 73 km2 (28 sq mi) and a 2011 census population of 15,550. The municipality of Santorini includes the inhabited islands of Santorini and Therasia, as well as the uninhabited islands of Nea Kameni, Palaia Kameni, Aspronisi and Christiana. The total land area is 90.623 km2 (34.990 sq mi).[2] Santorini is part of the Thira regional unit.[3]

Santorini / Thira

Σαντορίνη / Θήρα | |

|---|---|

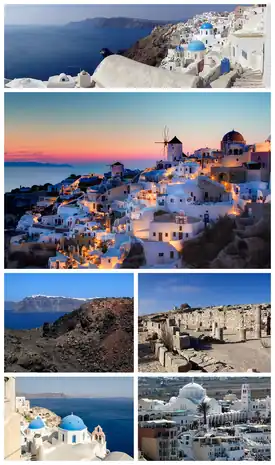

Clockwise from top: Partial panoramic view of Santorini, sunset in the village of Oia, ruins of the Stoa Basilica at Ancient Thera, the Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral of Ypapanti at the town of Fira, the Aegean Sea as seen from Oia, and view of Fira from the island of Nea Kameni at the Santorini caldera. | |

Santorini / Thira Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 36°24′54″N 25°25′57″E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | South Aegean |

| Regional unit | Thira |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Antonis Sigalas |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 90.69 km2 (35.02 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 15,550 |

| • Municipality density | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 14,005 |

| Community | |

| • Population | 1,857 (2011) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 847 00, 847 02 |

| Area code(s) | 22860 |

| Vehicle registration | EM |

| Website | www.thira.gr |

The island was the site of one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recorded history: the Minoan eruption (sometimes called the Thera eruption), which occurred about 3,600 years ago at the height of the Minoan civilization.[4] The eruption left a large caldera surrounded by volcanic ash deposits hundreds of metres deep.

It is the most active volcanic centre in the South Aegean Volcanic Arc, though what remains today is chiefly a water-filled caldera. The volcanic arc is approximately 500 km (300 mi) long and 20 to 40 km (12 to 25 mi) wide. The region first became volcanically active around 3–4 million years ago, though volcanism on Thera began around 2 million years ago with the extrusion of dacitic lavas from vents around Akrotiri.

Names

Santorini was named by the Latin Empire in the thirteenth century, and is a reference to Saint Irene, from the name of the old cathedral in the village of Perissa – the name Santorini is a contraction of the name Santa Irini.[4] Before then, it was known as Kallístē (Καλλίστη, "the most beautiful one"), Strongýlē (Στρογγύλη, "the circular one"),[5] or Thēra. The name Thera was revived in the nineteenth century as the official name of the island and its main city, but the colloquial name Santorini is still in popular use. Thera is the ancient name and it was called like this because of Theras, the leader of the Spartans who colonized it, and gave his name to the island.[6]

History

Minoan Akrotiri

Excavations starting in 1967 at the Akrotiri site under the late Professor Spyridon Marinatos have made Thera the best-known Minoan site outside Crete, homeland of the culture. The island was not known as Thera at this time. Only the southern tip of a large town has been uncovered, yet it has revealed complexes of multi-level buildings, streets, and squares with remains of walls standing as high as eight metres, all entombed in the solidified ash of the famous eruption of Thera. The site was not a palace-complex as found in Crete nor was it a conglomeration of merchant warehousing. Its excellent masonry and fine wall-paintings reveal a complex community. A loom-workshop suggests organized textile weaving for export. This Bronze Age civilization thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, reaching its peak in the period between 2000 and 1630 BC.[7]

Many of the houses in Akrotiri are major structures, some of them three storeys high. Its streets, squares, and walls were preserved in the layers of ejecta, sometimes as tall as eight metres, indicating this was a major town. In many houses stone staircases are still intact, and they contain huge ceramic storage jars (pithoi), mills, and pottery. Noted archaeological remains found in Akrotiri are wall paintings or frescoes that have kept their original colour well, as they were preserved under many metres of volcanic ash. Judging from the fine artwork, its citizens were sophisticated and relatively wealthy people. Among more complete frescoes found in one house are two antelopes painted with a confident calligraphic line, a man holding fish strung by their gills, a flotilla of pleasure boats that are accompanied by leaping dolphins, and a scene of women sitting in the shade of light canopies. Fragmentary wall-paintings found at one site are Minoan frescoes that depict "Saffron-gatherers" offering crocus-stamens to a seated woman, perhaps a goddess important to the Akrotiri culture. The themes of the Akrotiri frescoes show no relationship to the typical content of the Classical Greek décor of 510 BC to 323 BC that depict the Greek pantheon deities.

The town also had a highly developed drainage system. Pipes with running water and water closets found at Akrotiri are the oldest such utilities discovered. The pipes run in twin systems, indicating that Therans used both hot and cold water supplies. The origin of the hot water they circulated in the town probably was geothermic, given the volcano's proximity.

The well preserved ruins of the ancient town are often compared to the spectacular ruins at Pompeii in Italy. The canopy covering the ruins collapsed in an accident in September 2005, killing one tourist and injuring seven more. The site was closed for almost seven years while a new canopy was built. The site was re-opened in April 2012.

The oldest signs of human settlement are Late Neolithic (4th millennium BC or earlier), but c. 2000–1650 BC Akrotiri developed into one of the Aegean's major Bronze Age ports, with recovered objects that came not just from Crete, but also from Anatolia, Cyprus, Syria, and Egypt, as well as from the Dodecanese and the Greek mainland.

Dating of the Bronze Age eruption

The Minoan eruption provides a fixed point for the chronology of the second millennium BC in the Aegean, because evidence of the eruption occurs throughout the region and the site itself contains material culture from outside. The eruption occurred during the "Late Minoan IA" period of Minoan chronology at Crete and the "Late Cycladic I" period in the surrounding islands.

Archaeological evidence, based on the established chronology of Bronze Age Mediterranean cultures, dates the eruption to around 1500 BC.[8] These dates, however, conflict with radiocarbon dating which indicates that the eruption occurred at about 1645–1600 BC.[9] For those, and other reasons, the date of the eruption is disputed.

Ancient period

.jpg.webp)

Santorini remained unoccupied throughout the rest of the Bronze Age, during which time the Greeks took over Crete. At Knossos, in a LMIIIA context (14th century BC), seven Linear B texts while calling upon "all the deities" make sure to grant primacy to an elsewhere-unattested entity called qe-ra-si-ja and, once, qe-ra-si-jo. If the endings -ia[s] and -ios represent an ethnic suffix, then this means "The One From Qeras[os]". If the initial consonant were aspirated, then *Qhera- would have become "Thera-" in later Greek. "Therasia" and its ethnikon "Therasios" are both attested in later Greek; and, since -sos was itself a genitive suffix in the Aegean Sprachbund, *Qeras[os] could also shrink to *Qera. If qe-ra-si-ja was an ethnikon first, then in following the entity the Cretans also feared whence it came.[10]

Probably after what is called the Bronze Age collapse, Phoenicians founded a site on Thera. Herodotus reports that they called the island Callista and lived on it for eight generations.[11] In the ninth century BC, Dorians founded the main Hellenic city on Mesa Vouno, 396 m (1,299 ft) above sea level. This group later claimed that they had named the city and the island after their leader, Theras. Today, that city is referred to as Ancient Thera.

In his Argonautica, written in Hellenistic Egypt in the third century BC, Apollonius Rhodius includes an origin and sovereignty myth of Thera being given by Triton in Libya to the Greek Argonaut Euphemus, son of Poseidon, in the form of a clod of dirt. After carrying the dirt next to his heart for several days, Euphemus dreamt that he nursed the dirt with milk from his breast, and that the dirt turned into a beautiful woman with whom he had sex. The woman then told him that she was a daughter of Triton named Calliste, and that when he threw the dirt into the sea it would grow into an island for his descendants to live on. The poem goes on to claim that the island was named Thera after Euphemus' descendant Theras, son of Autesion, the leader of a group of refugee settlers from Lemnos.

The Dorians have left a number of inscriptions incised in stone, in the vicinity of the temple of Apollo, attesting to pederastic relations between the authors and their lovers (eromenoi). These inscriptions, found by Friedrich Hiller von Gaertringen, have been thought by some archaeologists to be of a ritual, celebratory nature, because of their large size, careful construction and – in some cases – execution by craftsmen other than the authors. According to Herodotus,[12] following a drought of seven years, Thera sent out colonists who founded a number of cities in northern Africa, including Cyrene. In the fifth century BC, Dorian Thera did not join the Delian League with Athens; and during the Peloponnesian War, Thera sided with Dorian Sparta, against Athens. The Athenians took the island during the war, but lost it again after the Battle of Aegospotami. During the Hellenistic period, the island was a major naval base for Ptolemaic Egypt.

Medieval and Ottoman period

As with other Greek territories, Thera then was ruled by the Romans. When the Roman Empire was divided, the island passed to the eastern side of the Empire which today is known as the Byzantine Empire.[13] According to George Cedrenus, the volcano erupted again in the summer of 727, the tenth year of the reign of Leo III the Isaurian.[14] He writes: "In the same year, in the summer, a vapour like an oven's fire boiled up for days out of the middle of the islands of Thera and Therasia from the depths of the sea, and the whole place burned like fire, little by little thickening and turning to stone, and the air seemed to be a fiery torch." This terrifying explosion was interpreted as a divine omen against the worship of religious icons[15][16] and gave the Emperor Leo III the Isaurian the justification he needed to begin implementing his Iconoclasm policy.

The name "Santorini" first appears c. 1153-1154 in the work of the Muslim geographer al-Idrisi, as "Santurin", from the island's patron saint, Saint Irene.[17] After the Fourth Crusade, it was occupied by the Duchy of Naxos which held it up to circa 1280 when it was reconquered by Licario (the claims of earlier historians that the island had been held by Jacopo I Barozzi and his son as a fief have been refuted in the second half of the twentieth century);[18][19][20] it was again reconquered from the Byzantines circa 1301 by Iacopo II Barozzi, a member of the Cretan branch of the Venetian Barozzi family, whose descendant held it until it was annexed in c. 1335 by Niccolo Sanudo after various legal and military conflicts.[21] In 1318–1331 and 1345–1360 it was raided by the Turkish principalities of Menteshe and Aydın, but did not suffer much damage.[17] Because of the Venetians the island became home to a sizable Catholic community and is still the seat of a Catholic bishopric.

From the 15th century on, the suzerainty of the Republic of Venice over the island was recognized in a series of treaties by the Ottoman Empire, but this did not stop Ottoman raids, until it was captured by the Ottoman admiral Piyale Pasha in 1576, as part of a process of annexation of most remaining Latin possessions in the Aegean.[17] It became part of the semi-autonomous domain of the Sultan's Jewish favourite, Joseph Nasi. Santorini retained its privileged position in the 17th century, but suffered in turn from Venetian raids during the frequent Ottoman–Venetian wars of the period, even though there were no Muslims on the island.[17]

Santorini was captured briefly by the Russians under Alexey Orlov during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, but returned to Ottoman control after.

19th century

In 1807, the islanders were forced by the Sublime Porte to send 50 sailors to Mykonos to serve in the Ottoman navy.[22]

In 1810, Santorini with 32 ships possessed the seventh largest of the Greek fleet after Kefallinia (118), Hydra (120), Psara (60), Ithaca (38) Spetsai (60) and Skopelos (35).[23]

During the last years of Ottoman rule, the majority of residents were farmers and seafarers who exported their abundant produce, while the level of education was improving on the island, with the Monastery of Profitis Ilias being one of the most important monastic centres in the Cyclades.[22]

In 1821 the island was home to 13,235 inhabitants, which within a year had risen to 15,428.[24]

Greek War of Independence

As part of its plans to foment a revolt against the Ottoman Empire and gain Greek Independence, Alexandros Ypsilantis, the head of the Filiki Eteria in early 1821, dispatched Dimitrios Themelis from Patmos and Evangelis Matzarakis (–1824), a sea captain from Kefalonia who had Santorini connections to establish a network of supporter in the Cyclades.[25] As his authority, Matzarakis had a letter from Ypsilantis (dated 29 December 1820) addressed to the notables of Santorini and the Orthodox metropolitan bishop Zacharias Kyriakos (served 1814–1842). At the time, the population of Santorini was divided between those who supported independence, and (particularly among the Catholics and non-Orthodox) those who were ambivalent or distrustful of a revolt being directed by Hydra and Spetses or were fearful of the Sultan's revenge. While the island didn't come out in direct support of the revolt, they did send 100 barrels of wine to the Greek fleet as well in April 1821, 71 sailors, a priest and the presbyter Nikolaos Dekazas, to serve on the Spetsiote fleet.[22]

Because of the lack of majority support for direct participation in the revolt, it was necessary for Matzarakis to enlist the aid of Kefalonians living in Santorini to, on 5 May 1821[22] (the feast day of the patron saint of the island), raise the flag of the revolution and then expel the Ottoman officials from the island.[25] The Provisional Administration of Greece organized the Aegean islands into six provinces, one of which was Santorini and appointed Matzarakis its governor in April 1822.[26][27] While he was able to raise a large amount of money (double that collected on Naxos), he was soon found to lack the diplomatic skills needed to convince the islanders who had enjoyed considerable autonomy to now accept direction from a central authority and contribute tax revenue to it. He claimed to his superiors that the islanders needed "political re-education" as they did not understand why they had to pay higher taxes than those levied under the Ottomans in order to support the struggle for independence. The hostility against the taxes caused many of the tax collectors to resign.

Things were also not helped by the governor's authoritarian character, arbitrariness and arrests of prominent islanders losing him the support of Zacharias Kyriakos, who had initially supported Matzarakis. In retaliation Matzarakis accused him of being a "Turkophile" and had the archbishop imprisoned and then exiled him. The abbots of the monasteries, the priests and the prelates, complained to Demetrios Ypsilantis, president of the National Assembly.

Matzarakis soon had to hire bodyguards as the island descended into open revolt against him.[25] Fearful for his life Matzarakis later fled the island,[25] and was dismissed from his governorship by Demetrios Ypsilantis. Mazarakis however later represented Santorini in the National Assembly and following his death was succeeded in that position in November 1824 by Pantoleon Augerino.

Once they heard of massacres of the Greek population of Chios in April 1822, many islanders became fearful of Ottoman reprisals, with two villages stating they were prepared to surrender,[25] though sixteen monks from the Monastery of Profitis Ilias, led by their abbot Gerasimos Mavrommatis declared in writing their support for the revolt.[28] Four commissioners for the Aegean islands (among them, Benjamin of Lesvos and Konstantinos Metaxas) appointed by the Provisional Administration of Greece arrived in July 1822 to investigate the issues on Santorini. The commissioners were uncompromising in their support for Matzarakis. With news from Chios fresh in their minds the island's notables eventually arrested Metaxas, with the intention of handing him over to the Ottomans in order to prove their loyalty. He was rescued by his Ionian guards.

Matters became so heated that Antonios Barbarigos (- 1824) who had been serving in the First National Assembly at Epidaurus since 20 January 1820 was seriously wounded in the head by a knife attack on Santorini in October 1822 during a dispute between the factions. In early 1823, the Second National Assembly at Astros, imposed a contribution of 90,000 grosis on Santorini to fund the fight for independence, while in 1836 they also had to contribute in 1826 to the obligatory loan of 190,000 grosis imposed on the Cyclades.[24]

In decree 573 issued by the National Assembly 17 May 1823 Santorini was recognized as one of 15 provinces in the Greek controlled Aegean (nine in the Cyclades and six in the Sporades).[26]

The island became part of the fledgling Greek state under the London Protocol of 3 February 1830, rebelled against the government of Ioannis Kapodistrias in 1831, and became definitively part of the independent Kingdom of Greece in 1832, with the Treaty of Constantinople.[17]

Santorini joined an insurrection that had broken out in Nafplio on 1 February 1862 against the rule of King Otto of Greece. However, the royal authorities was able to quickly restore control and the revolt had been suppressed by 20 March of that year. However, the unrest arose again later in the year which lead to the 23 October 1862 Revolution and the overthrow of King Otto.

World War II

During the Second World War, Santorini was occupied in 1941 by Italian forces and then by the Germans following the Italian armistice in 1943. In 1944, the German garrison on Santorini was raided by a group of British Special Boat Service Commandos, killing most of its men. Five locals were later shot in reprisal, including the mayor.[29][30]

Post-war

In general the island's economy continued to decline following World War II with a number of factories closing as a lot of industrial activity relocated after to Athens. In an attempt to improve the local economy the Union of Santorini Cooperatives was established 1947 to process, export and promote the islands agriculture products, in particular its wine. In 1952 they constructed near the village of Monolithos what is today the island's only remaining tomato processing factory. The island's tourism in the early 1950s generally took the form of small numbers of wealthy tourists on yacht cruises though the Aegean. The island's children would present arriving passengers with flowers and bid them happy sailing by lighting small lanterns along the steps from Fira down to the port, offering them a beautiful farewell spectacle. Once such visitor was the actress Olivia de Havilland who visited the island in September 1955 at the invitation of Petros Nomikos.[31]

In the early 1950s the shipping magnate Evangelos P. Nomikos and his wife Loula decided to support their birthplace and so asked residents to choose whether they wanted the couple to pay for the construction of either a hotel or a hospital, to which local authorities replied that they would prefer a hotel. As a result, in 1952, the Nomikos' commissioned the architect Venetsanos to undertake the design and paid for the construction of the Hotel Atlantis, which was at the time the most glamorous hotel in the Cyclades.[32]

In 1954, Santorini had approximately 12,000 inhabitants and very few visitors. The only modes of transport on the island were a jeep, a small bus and the island's traditional donkeys and mules.

1956 earthquake

At 3.11 am on 9 July 1956 an earthquake with a magnitude (depending on the particular study) of 7.5,[33] 7.6,[33] 7.7[34] or 7.8[35] struck 30 km south of the island of Amorgos. It was the largest earthquake of the 20th century in Greece and had a devastating impact on Santorini.[35][34] It was followed by aftershocks, the most significant being the first occurring at 03:24, 13 minutes after the main shock, which had a 7.2 magnitude.[35] This aftershock which originated close to the island of Anafi is believed to have been responsible for most of the damage and casualties on Santorini.[35] The earthquake was accompanied by a tsunami which while much higher at other islands is estimated to have reached 3 metres at Perissa and 2 metres at Vlichada on Santorini.[35]

Immediately following the earthquake the Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Karamanlis declared Santorini a state of "large-scale local disaster" and visited the island to inspect the situation on 14 July.[36]

Many countries have offered to send relief efforts, though Greece refused to accept the offer of the United Kingdom to send warships to help from Cyprus where they were involved in the Cyprus Emergency.[36]

As there was no airport the Greek military made air drops of food, tents and supplies, while camps for the homeless were established on the outskirts of Fira.[37]

On Santorini the earthquakes killed 53 people and injured another 100.[38][36] On Santorini 35% of the houses collapsed and 45% suffered major or minor damage.[36] In total, 529 houses were destroyed, 1,482 were severely damaged and 1,750 lightly damaged.[36] Almost all public buildings were completely destroyed. One of the largest buildings that survived unscathed was the newly built Hotel Atlantis, which allowed it to be used as a temporary hospital and to house public services. The greatest damage was experienced on the Western side along the edge of the caldera, especially at Oia, with parts of the ground collapsing into the sea. The damage from the earthquake reduced most of the population to extreme poverty and caused many to leave the island in search of better opportunities with most settling in Athens.[36]

Tourism

The expansion of tourism in recent years has resulted in the growth of the economy and population. Santorini was ranked the world's top island by many magazines and travel sites, including the Travel+Leisure Magazine,[39] the BBC,[40] as well as the US News.[41] An estimated 2 million tourists visit annually.[42] In recent years, Santorini has been emphasising sustainable development and the promotion of special forms of tourism, the organization of major events such as conferences and sport activities.

The island's pumice quarries have been closed since 1986, in order to preserve the caldera. In 2007, the cruise ship MS Sea Diamond ran aground and sank inside the caldera. As of 2019, Santorini is a particular draw for Asian couples who come to Santorini to have pre-wedding photos taken against the backdrop of the island's landscape.[43]

Geography

Geological setting

The Cyclades are part of a metamorphic complex that is known as the Cycladic Massif. The complex formed during the Miocene and was folded and metamorphosed during the Alpine orogeny around 60 million years ago. Thera is built upon a small non-volcanic basement that represents the former non-volcanic island, which was approximately 9 by 6 km (5.6 by 3.7 mi). The basement rock is primarily composed of metamorphosed limestone and schist, which date from the Alpine Orogeny. These non-volcanic rocks are exposed at Mikro Profititis Ilias, Mesa Vouno, the Gavrillos ridge, Pyrgos, Monolithos, and the inner side of the caldera wall between Cape Plaka and Athinios.

The metamorphic grade is a blueschist facies, which results from tectonic deformation by the subduction of the African Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate. Subduction occurred between the Oligocene and the Miocene, and the metamorphic grade represents the southernmost extent of the Cycladic blueschist belt.

Volcanism

Volcanism on Santorini is due to the Hellenic subduction zone southwest of Crete. The oceanic crust of the northern margin of the African Plate is being subducted under Greece and the Aegean Sea, which is thinned continental crust. The subduction compels the formation of the Hellenic arc, which includes Santorini and other volcanic centres, such as Methana, Milos, and Kos.[44]

The island is the result of repeated sequences of shield volcano construction followed by caldera collapse.[45] The inner coast around the caldera is a sheer precipice of more than 300 m (980 ft) drop at its highest, and exhibits the various layers of solidified lava on top of each other, and the main towns perched on the crest. The ground then slopes outwards and downwards towards the outer perimeter, and the outer beaches are smooth and shallow. Beach sand colour depends on which geological layer is exposed; there are beaches with sand or pebbles made of solidified lava of various colours: such as the Red Beach, the Black Beach and the White Beach. The water at the darker coloured beaches is significantly warmer because the lava acts as a heat absorber.

The area of Santorini incorporates a group of islands created by volcanoes, spanning across Thera, Thirasia, Aspronisi, Palea, and Nea Kameni.

Santorini has erupted many times, with varying degrees of explosivity. There have been at least twelve large explosive eruptions, of which at least four were caldera-forming.[44] The most famous eruption is the Minoan eruption, detailed below. Eruptive products range from basalt all the way to rhyolite, and the rhyolitic products are associated with the most explosive eruptions.

The earliest eruptions, many of which were submarine, were on the Akrotiri Peninsula, and active between 650,000 and 550,000 years ago.[44] These are geochemically distinct from the later volcanism, as they contain amphiboles.

Over the past 360,000 years there have been two major cycles, each culminating with two caldera-forming eruptions. The cycles end when the magma evolves to a rhyolitic composition, causing the most explosive eruptions. In between the caldera-forming eruptions are a series of sub-cycles. Lava flows and small explosive eruptions build up cones, which are thought to impede the flow of magma to the surface.[44] This allows the formation of large magma chambers, in which the magma can evolve to more silicic compositions. Once this happens, a large explosive eruption destroys the cone. The Kameni islands in the centre of the lagoon are the most recent example of a cone built by this volcano, with much of them hidden beneath the water.

Minoan eruption

During the Bronze Age, Santorini was the site of the Minoan eruption, one of the largest volcanic eruptions in human history. This violent eruption was centred on a small island just north of the existing island of Nea Kameni in the centre of the caldera; the caldera itself was formed several hundred thousand years ago by the collapse of the centre of a circular island, caused by the emptying of the magma chamber during an eruption. It has been filled several times by ignimbrite since then, and the process repeated itself, most recently 21,000 years ago. The northern part of the caldera was refilled by the volcano, then collapsed once more during the Minoan eruption. Before the Minoan eruption, the caldera formed a nearly continuous ring with the only entrance between the tiny island of Aspronisi and Thera; the eruption destroyed the sections of the ring between Aspronisi and Therasia, and between Therasia and Thera, creating two new channels.

On Santorini, a deposit of white tephra thrown from the eruption is found lying up to 60 m (200 ft) thick, overlying the soil marking the ground level before the eruption, and forming a layer divided into three fairly distinct bands indicating different phases of the eruption. Archaeological discoveries in 2006 by a team of international scientists revealed that the Santorini event was much more massive than previously thought; it expelled 61 km3 (15 cu mi) of magma and rock into the Earth's atmosphere, compared to previous estimates of only 39 km3 (9.4 cu mi) in 1991,[46][47] producing an estimated 100 km3 (24 cu mi) of tephra. Only the Mount Tambora volcanic eruption of 1815, the 181 AD eruption of the Taupo Volcano, and possibly Baekdu Mountain's 946 AD eruption have released more material into the atmosphere during the past 5,000 years.

The Minoan eruption has been considered as possible inspiration for ancient stories including Atlantis and the Exodus. These hypotheses are not supported by current archaeological research, but remain popular in pseudohistory and pseudoarchaeology.

Post-Minoan volcanism

Post-Minoan eruptive activity is concentrated on the Kameni islands, in the centre of the lagoon. They have been formed since the Minoan eruption, and the first of them broke the surface of the sea in 197 BC.[44] Nine subaerial eruptions are recorded in the historical record since that time, with the most recent ending in 1950.

In 1707 an undersea volcano breached the sea surface, forming the current centre of activity at Nea Kameni in the centre of the lagoon, and eruptions centred on it continue – the twentieth century saw three such, the last in 1950. Santorini was also struck by a devastating earthquake in 1956. Although the volcano is dormant at the present time, at the current active crater (there are several former craters on Nea Kameni), steam and carbon dioxide are given off.

Small tremors and reports of strange gaseous odours over the course of 2011 and 2012 prompted satellite radar technological analyses and these revealed the source of the symptoms; the magma chamber under the volcano was swollen by a rush of molten rock by 10 to 20 million cubic metres between January 2011 and April 2012, which also caused parts of the island's surface to rise out of the water by a reported 8 to 14 centimetres.[48] Scientists say that the injection of molten rock was equivalent to 20 years' worth of regular activity.[48]

Climate

According to the National Observatory of Athens Santorini has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh) with Mediterranean (Csa) characteristics, such as the dry summers and the relatively wetter winters. It has an average annual precipitation of around 280 mm and an average annual temperature of around 19°C.[49][50]

| Climate data for Santorini | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.1 (86.2) |

27.1 (80.8) |

22.6 (72.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.6 (71.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.9 (53.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

10.4 (50.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 56.2 (2.21) |

45.4 (1.79) |

48.8 (1.92) |

10.4 (0.41) |

6.9 (0.27) |

1.9 (0.07) |

0.04 (0.00) |

2.8 (0.11) |

3.5 (0.14) |

17.9 (0.70) |

36.6 (1.44) |

51.8 (2.04) |

282.24 (11.1) |

| Source: National Observatory of Athens Monthly Bulletins (Jul 2013-Mar 2023)[51][52] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Santorini's primary industry is tourism, particularly in the summer months. Agriculture also forms part of its economy, and the island sustains a wine industry. The economic life of Santorini before 1960, when the flow of foreign visitors to the island for tourist purposes gradually began, was based on crops and trade.

Agriculture

.jpg.webp)

In the middle of the 19th century, Santorini presents a great commercial activity with foreign countries and especially with Russia, where it exports all its produced wine.[53][54] Because of its unique ecology and climate - and especially its volcanic ash soil - Santorini is home to unique and prized produce such as the Santorini cherry tomato. Viticulture, whose history goes back to prehistoric times, could not remain unaffected by the rapid increase in tourism, where there was a gradual decrease until 1997. Although today viticulture is the most important sector of agricultural production in Santorini and now traditional throughout Greece.

Wine industry

The island remains the home of a small, but flourishing, wine industry, based on the indigenous Assyrtiko grape variety, with auxiliary cultivations of Aegean white varieties such as Athiri and Aidani and the red varieties such as Mavrotragano and Mandilaria. The vines are extremely old and resistant to phylloxera (attributed by local winemakers to the well-drained volcanic soil and its chemistry), so the vines needed no replacement during the great phylloxera epidemic of the late 19th century. In their adaptation to their habitat, such vines are planted far apart, as their principal source of moisture is dew, and they often are trained in the shape of low-spiralling baskets, with the grapes hanging inside to protect them from the winds.[55]

The viticultural pride of the island is the sweet and strong Vinsanto (Italian: "holy wine"), a dessert wine made from the best sun-dried Assyrtiko, Athiri, and Aidani grapes, and undergoing long barrel aging (up to twenty or twenty-five years for the top cuvées). It matures to a sweet, dark, amber-orange unctuous dessert wine that has achieved worldwide fame, possessing the standard Assyrtiko aromas of citrus and minerals, layered with overtones of nuts, raisins, figs, honey, and tea.

White wines from the island are extremely dry with a strong citrus scent and mineral and iodide salt aromas contributed by the ashy volcanic soil, whereas barrel aging gives to some of the white wines a slight frankincense aroma, much like Vinsanto. It is not easy to be a winegrower in Santorini; the hot and dry conditions give the soil a very low productivity. The yield per hectare is only 10 to 20% of the yields that are common in France or California. The island's wines are standardised and protected by the "Vinsanto" and "Santorini" OPAP designations of origin.[56]

Brewing

A brewery, the Santorini Brewing Company, began operating out of Santorini in 2011, based in the island's wine region.[57]

Governance

The present municipality of Thera (officially: "Thira", Greek: Δήμος Θήρας),[58][59] which covers all settlements on the islands of Santorini and Therasia, was formed at the 2011 local government reform, by the merger of the former Oia and Thera municipalities.[3]

Oia is now called a Κοινότητα (community), within the municipality of Thera, and it consists of the local subdivisions (Greek: τοπικό διαμέρισμα) of Therasia and Oia.

The municipality of Thera includes an additional 12 local subdivisions on Santorini island: Akrotiri, Emporio, Episkopis Gonia, Exo Gonia, Imerovigli, Karterados, Megalohori, Mesaria, Pyrgos Kallistis, Thera (the seat of the municipality), Vothon, and Vourvoulos.[60]

Towns and villages

- Akrotiri

- Ammoudi

- Athinios

- Emporio

- Finika

- Fira

- Firostefani

- Imerovigli

- Kamari

- Karterados

- Messaria

- Monolithos

- Oia

- Perissa

- Pyrgos Kallistis

- Vothonas

- Vourvoulos

Attractions

Architecture

The traditional architecture of Santorini is similar to that of the other Cyclades, with low-lying cubical houses, made of local stone and whitewashed or limewashed with various volcanic ashes used as colours. These colours, in recent years, tend to replace white in the colour of house façades, according to the traditional architecture of the island as it was developed until the great earthquake of 1956. The unique characteristic is the common utilisation of the hypóskapha: extensions of houses dug sideways or downwards into the surrounding pumice. These rooms are prized because of the high insulation provided by the air-filled pumice, and are used as living quarters of unique coolness in the summer and warmth in the winter. These are premium storage space for produce, especially for wine cellaring: the Kánava wineries of Santorini.

When strong earthquakes struck the island in 1956, half the buildings were completely destroyed and a large number suffered repairable damage. The underground dwellings along the ridge overlooking the caldera, where the instability of the soil was responsible for the great extent of the damage, needed to be evacuated. Most of the population of Santorini had to emigrate to Piraeus and Athens.[61]

%252C_Greece-2.jpg.webp)

Fortifications

During the 15th and 16th centuries the Cyclades were under threat from pirates who plundered the harvests, enslaved men and women and sold them in the slave markets. The small bays of the island were also ideal as hideouts. In response the islanders built their settlements at the highest most inaccessible points, and very close to, or on top of, each other; while their external walls, devoid of openings, formed a protective perimeter around the village. In addition the following additional types of fortifications were built throughout the island to protect the island's inhabitants.

- Casteli (castles), also written as kasteli, were large fortified permanent settlements. There were five on the island, Agios Nikolaos (at Oia), Akrotiri, Emborio, Pyrgos, and Skaros. At the entrance to every casteli was a church dedicated to Agia (St.) Theodosia, the Protector-Saint of castles.

- Goulas (from the Turkish word kule which means 'tower'[62]) were multi-storey, rectangular, and the highest tower of most kastelli. There were four goulas on the island. They were used both as an observatory and as a place of refuge for the islanders. They had thick walls, parapets, an iron gate, murder holes, and embrasures.

- Viglio were small coastal watchtowers, which were permanently garrisoned, from where a watch was maintained and an alarm raised when a pirate ship was sighted.

Infrastructure

Electricity

Electricity for both Santorini and Therasia is principally supplied from the Thira Autonomous Power Station which is located at Monolithos in the eastern part of Santorini. Owned by Public Power Corporation (PPC) it has generators powered by diesel engines and gas turbines. The two islands have a total installed capacity of 75.09 MW of thermal generation and 0.25 MW of renewable generation.[63] There is a programme underway at a cost of €124 million as part of the Cyclades Interconnection Project to connect the island via a submarine cable to Naxos and hence by extension to the mainland system by 2023.[64]

A fire at the power station in Monolithos on 13 August 2018 put it out of service, resulting in a total loss of electricity supply across the two islands. Within four days electricity had been restored to all but 10% of the islands' consumers. Vessels were dispatched to carry two power generators to assist in supporting the restoration of the electricity supply.[65][66]

Electricity is distributed around the island by The Hellenic Electricity Distribution System Operator (HEDNO S.A. or DEDDIE S.A.) which is a 100% owned subsidiary of PPC. A cable connects the Thirasia and Santorini electrical distribution systems.

Transportation

The central bus station is in Fira, the capital of the island, where buses depart very frequently. They cover routes to almost all places around the island and to most tourist spots.

Apart from its connection with other Cyclades islands, Santorini is also connected by ferry with Piraeus on a daily basis all year long, with up to 5 direct crossings during summer.

Airport

Santorini is one of the few Cyclades Islands with a major airport, which lies about 6 km (4 mi) southeast of downtown Thera. The main asphalt runway (16L-34R) is 2,125 m (6,972 ft) in length, and the parallel taxiway was built to runway specification (16R-34L). It can accommodate Boeing 757, Boeing 737, Airbus 320 series, Avro RJ, Fokker 70, and ATR 72 aircraft. Scheduled airlines include the new Olympic Air, Aegean Airlines, Ryanair, and Sky Express, with flights chartered from other airlines during the summer, and with transport to and from the air terminal available through buses, taxis, hotel car-pickups, and hire cars.

Land

Bus services link Fira to most parts of the island.[67]

Ports

Santorini has two ports: Athinios (Ferry Port) and Skala (Old Port).[68] Cruise ships anchor off Skala and passengers are transferred by local boatmen to shore at Skala where Fira is accessed by cable car, on foot or by donkeys and mules. The use of donkeys for tourist transportation has attracted significant criticism from animal rights organisations for animal abuse and neglect, including failure to provide the donkeys with sufficient water or rest. [69] Tour boats depart from Skala for Nea Kameni and other Santorini destinations.[70]

Water and sewerage

As the island lies in a rain shadow between the mountains of Crete and the Peloponnese water seems to have been scarce at least from post-eruption times.[71] This, combined with the small size of the island, the lack of rivers, and the nature of the soil, which is largely composed of volcanic ash, as well as the high summer temperatures meant that there was very little surface water.[72] With only one spring (Zoodochos Pigi – the Life-giving Spring) this encouraged the practice of diverting any rain that fell on roofs and courtyards to elaborate underground cisterns, supplemented in the 20th century with water imported from other areas of Greece. Owing to the lack of water islanders developed non-irrigated crops such as vines and olives that could survive on only the scant moisture provided by the common early-morning fog condensing on the ground as dew.

Many cisterns ceased to be used following the 1956 earthquake. As tourism increased, the existing rainwater harvesting methods proved incapable of supplying the increased demand. As a result, it has become necessary to construct desalination plants which now provide running but non-potable water to most residents. This has led to many of the historic cisterns falling into disrepair.[73]

The first desalination plant was built at Oia following a donation in 1992 by the Oia-born businessman Aristeidis Alafouzos. By 2003 the plant had expanded to house three desalination units (of which two had been donated by Alafouzos).[74] As of 2020 the plant has six desalination units with a total capacity of 2,800 m3 (99,000 cu ft) per day.[75]

In addition to Oia there are currently desalination plants at Aghia Paraskevi, located on the southwest side of the airport with a capacity of 5,000 m3 (180,000 cu ft) per day which supplies Kamari, Vothonas, Messaria, Exo Gonia, Mesa Gonia, Agia Paraskevi, and Monolithos;[76] Fira with a capacity of 1,200 m3 (42,000 cu ft) per day;[75] Akrotiri (also known as the Cape) which has two units with a total capacity of 650 m3 (23,000 cu ft) per day;[75] Exo Gialos which has two units with a total capacity of 2,000 m3 (71,000 cu ft) per day which supplies Fira, Imerovigli, Karteradou, Pyrgos, Megalochori and Vourvoulou;[77] and Therasia which has two TEMAK units with a total capacity of 350 m3 (12,000 cu ft) per day.[75]

There are also a number of small autonomous drinking water production units with a capacity of 6 m3 (210 cu ft) per day located at Kamari, Emporio, Messaria and Thirasia Island.[75]

The provision of water supply and sewage treatment and disposal on both Santorini and Therasia Islands is undertaken by the municipally owned DEYA Thiras. It was founded in May 2011, after the merging of the Municipal Water Supply and Sewerage Company of Thera (DEYA Thera) and the Community Water Supply and Sewerage Company of Oia (K .Ε.Υ.Α. Οίας). Known as DEYATH it is responsible for the planning, construction, management, operation and maintenance of the water supply system (desalination plants and pumping wells), irrigation, drainage, and the wastewater collection networks and treatment plants for the islands of Thira (Santorini) and Therasia. The Loulas and Evangelos Nomikos Foundation has funded a number of projects aimed at improving the water supply and sewage systems on the islands.

Notable people

- Aristeidis Alafouzos businessman

- Giannis Alafouzos, former president of Panathinaikos F.C.

- Mariza Koch, singer

- Spyros Markezinis, politician

- Themison of Thera

In popular culture

The movie Summer Lovers (1982) was filmed on location here.[78]

The island was a featured filming location in the 2005 film The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and its sequel.[79]

Santorini inspired French pop singer-songwriter Nolwenn Leroy for her song "Mystère", released on her 2005 album Histoires Naturelles ("Aux criques de Santorin").[80]

The Santorini Film Festival is held annually at the open-air cinema, Cinema Kamari, in Santorini.[81]

American hip hop musician Rick Ross has a song titled "Santorini Greece", and its 2017 music video was shot on the island.[82]

The 2018 video game Assassin's Creed Odyssey features a DLC extra entitled Fate of Atlantis, in which a gateway to the mythical lost city of Atlantis is located in a temple beneath the island of Thera.[83]

In Pokémon Ruby and Sapphire and their remakes, the landscape of Sootopolis City was modelled on that of Santorini.[84]

The board game Santorini, inspired by the architecture of the island's cliffside villages, was published in 2004 by Gordon Hamilton.[85]

References

Notes

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text". Government Gazette (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 336–337. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- C. Doumas (editor). Thera and the Aegean world: papers presented at the second international scientific congress, Santorini, Greece, August 1978. London, 1978. ISBN 0-9506133-0-4

- Harry Thurston Peck, Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities (1898), Theras

- TheModernAntiquarian.com Archived 2012-10-29 at the Wayback Machine, C. Michael Hogan, Akrotiri, The Modern Antiquarian (2007).

- Warren, Peter M. (2006). "The Date of the Thera Eruption in Relation to Aegean-Egyptian Interconnections and the Egyptian Historical Chronology". In Czerny E.; Hein I.; Hunger H.; Melman D.; Schwab A. (eds.). Timelines: Studies in Honour of Manfred Bietak. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 149. Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Peeters. pp. 2: 305–21. ISBN 978-90-429-1730-9.

- Manning, Stuart W.; Ramsey, C.B.; Kutschera, W.; Higham, T.; Kromer, B.; Steier, P.; Wild, E.M. (2006). "Chronology for the Aegean Late Bronze Age 1700–1400 B.C." Science. 312 (5773): 565–69. Bibcode:2006Sci...312..565M. doi:10.1126/science.1125682. PMID 16645092. S2CID 21557268. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- TheraFoundation.org, Minoan Qe-Ra-Si-Ja. The Religious Impact of the Thera Volcano on Minoan Crete. Archived 2006-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Hist. IV.147

- Hist. IV.149–165

- "Thera - The Ancient City". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 2020-06-29. Archived from the original on 2020-07-03. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- George Cedrenus, Σύνοψις ἱστορίων, Vol I, p. 795.

- Theophanes the Confessor, Chronography pp. 621-622 : «ος [ο Λέων] την κατ’ αυτού θείαν οργήν υπέρ εαυτού λογισάμενος». Νικηφόρος σελ. 64 : «Ταύτά φασιν ακούσαντα τον βασιλέα υπολαμβάνειν θείας οργής είναι μηνύματα».

- Ioannis Panagiotopoulos, «Το ηφαίστειο της Θήρας και η Eικονομαχία». Θεολογία 80 (2009), 235-253

- Savvides, A. (1997). "Santurin Adasi̊". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IX: San–Sze (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Silvano Borsari, "Studi sulle colonie veneziane in Romania nel XIII secolo", 1966, pp.35-37 and 79

- Louise Buenger Robbert (1985). "Venice and the Crusades". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Zacour, Norman P.; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume V: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 379–451. ISBN 0-299-09140-6. p. 432

- Marina Koumanoudi, "The Latins in the Aegean after 1204: Interdependence and Interwoven Interests," in Urbs capta: The Fourth Crusade and its Consequences, 2005, p.262

- Marina Koumanoudi, "The Latins in the Aegean after 1204: Interdependence and Interwoven Interests," in Urbs capta: The Fourth Crusade and its Consequences, 2005, p.263

- "Σημεία αντιφώνησης του Προέδρου της Δημοκρατίας κ.Προκοπίου Παυλοπούλου κατά την ανακήρυξή του σ' Επίτιμο Δημότη του Δήμου Θήρας" [Reply to the President of the Republic Mr. Prokopiou Pavlopoulos during his proclamation as Honorary Citizen of the Municipality of Thira] (in Greek). Presidency of the Hellenic Republic. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- Economou, Emmanouil M.L.; Kyriazis, Nicholas C.; Prassa, Annita (2016). "The Greek Merchant Fleet as a National Navy During the War of Independence 1800-1830" (PDF). MPRA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- "Σαντορίνη και Επανάσταση του 1821" [Santorini and the Revolution of 1821]. Rssing. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Mazower, Mark (2021). The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe (Hardback). Allen Lane. pp. 144, 148, 157–160. ISBN 978-0-241-00410-4.

- "Σφραγιδεσ Ελευθεριασ 1821-1832: Σφραγίδες Κοινοτήτων - Μοναστηρίων Προσωρινής Διοικήσεως τής Ελλάδος' Ελληνικής Πολιτείας" [Seals of Freedom 1821-1832: Seals of Communities - Monasteries of Provisional Administration of Greece, Greek State] (PDF). Historical and Ethnologica' Society of Greece. 1983. pp. 43, 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Μαντζαράκης Ευαγγέλης: (Μαντζοράκης, Μαντσαράκης Γλυκούδης, Ματζαράκης Ευάγγελος)" [Mantzarakis Evangelis: (Mantzorakis, Mantsarakis Glykoudis, Matzarakis Evangelos)]. Foundation of the Greek Parliament for Parliamentarism and Democracy. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Η Ιερά Μονή Προφήτου Ηλιού Θήρας" [The Holy Monastery of Profitos Ilios Thira]. Ιερά Μονή Προφήτου Ηλιού Θήρας. 31 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Mortimer, Gavin. The Special Boat Squadron in WW2, Osprey, 2013, ISBN 1782001891.

- Lewis, Damien (2014). Churchill's Secret Warriors. Quercus. ISBN 978-1848669178.

- Amburn, Ellis (2018). Olivia de Havilland and the Golden Age of Hollywood (Hardback). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-4930-3409-3.

- "Hotel Atlantis: Our History". Hotel Atlantis. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- Tsampouraki-Kraounaki, Konstantina; Sakellariou, Dimitris; Rousakis, Grigoris; Morfis, Ioannis; Panagiotopoulos, Ioannis; Livanos, Isidoros; Manta, Kyriaki; Paraschos, Fratzeska; Papatheodorou, George (2021). "The Santorini-Amorgos Shear Zone: Evidence for Dextral Transtension in the South Aegean Back-Arc Region, Greece". Geosciences. Basel, Switzerland: MDPI. 11 (5): 216. Bibcode:2021Geosc..11..216T. doi:10.3390/geosciences11050216. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- Papadimitriou, Eleftheria; Sourlas, Georgios; Karakostas, Vassilios (2005). "Seismicity Variations in the Southern Aegean, Greece, Before and After the Large (M7.7) 1956 Amorgos Earthquake Due to Evolving Stress". Pure and Applied Geophysics. 162 (5): 783–804. Bibcode:2005PApGe.162..783P. doi:10.1007/s00024-004-2641-z. S2CID 140605036.

- Okal, Emile A.; Synolakis, Costas E.; Uslu, Burak; Kalligeris, Nikos; Voukouvalas, Evangelos (2009). "The 1956 earthquake and tsunami in Amorgos, Greece". Geophysical Journal International. 178 (3): 1533–1554. Bibcode:2009GeoJI.178.1533O. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04237.x.

- Simos, Andriana (9 July 2020). "On This Day: The 1956 Santorini earthquake and its devastating aftermath". The Greek Herald. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- "20 Still Missing In Aegean Quake", New York Times, p. 5, 11 July 1956, archived from the original on 24 April 2022, retrieved 20 March 2022

- Sedgwick, A.C. (10 July 1956), "Quake, Tidal Wave Hit Aegean; At Least 42 Dead in Greek Isles", New York Times, pp. 1, 6, archived from the original on 24 April 2022, retrieved 20 March 2022

- "2011 World's Best Awards". Travel+Leisure. Archived from the original on 2011-07-12. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- "World's Best Islands". BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- "World's Best Island". US News. Archived from the original on 2014-04-08. Retrieved 2014-04-01.

- Smith, Helena (28 August 2017). "Santorini's popularity soars but locals say it has hit saturation point". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- Horowitz, Jason; Boushnak, Laura (6 August 2019). "The Bride, the Groom and the Greek Sunset: A Perfect Wedding Picture". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Druitt, Timothy H.; L. Edwards; R.M. Mellors; D.M. Pyle; R.S.J. Sparks; M. Lanphere; M. Davies; B. Barriero (1999). Santorini Volcano. Geological Society Memoir. Vol. 19. London: Geological Society. ISBN 978-1-86239-048-5.

- "Geology of Santorini". Volcano Discovery. Archived from the original on 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- URI.edu Archived 2015-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, URI Department of Communications and Marketing

- NationalGeographic.com Archived 2009-03-02 at the Wayback Machine, "Atlantis" Eruption Twice as Big as Previously Believed, Study Suggests.

- Brian Handwerk (12 September 2012). "Santorini Bulges as Magma Balloons Underneath". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 20 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- "Monthly Bulletins". www.meteo.gr. Archived from the original on 2023-02-02. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- "Latest Conditions in Santorini". Archived from the original on 2023-04-17. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- "Monthly Bulletins". www.meteo.gr.

- "Weather station of Santorini". Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- Gilis, Odysseas. "Οδυσσέας Γκιλής. ΘΗΡΑ ΣΑΝΤΟΡΙΝΗ ΣΤΡΟΓΓΥΛΗ ΚΑΛΛΙΣΤΗ" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2023-04-12. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- "Santorini". Archived from the original on 2023-04-11. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- An early observer of this was Theodore Bent in January 1884: "[At] Santorin they always weave the tendrils of their vines into circles, the effect in winter being that each vineyard looks as if hampers were placed all over it in rows and at intervals of every two yards." (The Cyclades, or Life Among the Insular Greeks. London, 1885, p. 41).

- "Greece Santorini History". www.greecesantorini.com. Archived from the original on 2016-02-23. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- "Greece's Handcrafted Beers Hit the Spot | GreekReporter.com". greece.greekreporter.com. 16 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- "Δήμος Θήρας, the official municipal government website" (in Greek). Archived from the original on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Municipality of Thira, English language version of the official municipal government website". Archived from the original on 2012-07-27. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Spreadsheet table of all administrative subdivisions in Greece, and their population as of the 18 March 2001 census" (Excel). Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Interior, Decentralization and E-government. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- "Restoration, Reconstruction and Simulacra" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-07. Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- Σπηλιοπούλου Ι.-Κωτσάκης Α., Οι Πύργοι και οι οχυρωμένες κατοικίες των νησιών του Αιγαίου και της Πελοποννήσου (14ος-19ος αι.), Eoa Kai Esperia, 8 (2013) pp.254-255 Archived 2022-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- GeoEnergy, Think (2018-01-19). "Greek island of Santorini partners with PPC Renewables on geothermal project | ThinkGeoEnergy - Geothermal Energy News". Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- "Santorini-Naxos grid link tender set to be announced by IPTO". Energy Press. December 29, 2020. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- "Interior, tourism ministers to Santorini to check power problems". ekathimerini. August 16, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- "Power supply returning to normal on Santorini". ekathimerini. August 17, 2013. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "Santorini Public Buses". www.ktel-santorini.gr. Archived from the original on 2019-06-15. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- Santorini Port Authority http://www.santorini-port.com Archived 2014-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Greek island accused of abusing its star attraction: donkeys". DW.COM. July 8, 2019. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- Santorini Port Authority http://www.santoriniport.com Archived 2014-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- "Santorini Water Museum, Greece". Water Museums. July 25, 1995. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Bitis, Ioannis (2013). "Water supply methods in Ancient Thera: the case of the sanctuary of Apollo Karneios". Water Supply. 13 (3): 638–645. doi:10.2166/ws.2013.017.

- Enriquez, Jared; Tipping, David C.; Lee, Jung-Ju; Vijay, Abhinav; Kenny, Laura; Chen, Susan; Mainas, Nikolaos; Holst-Warhaft, Gail; Steenhuis, Tammo (2017). "Water Management in the Tourism Economy: Linking the Mediterranean's Traditional Rainwater Cisterns to Modern Needs". Water. 9 (11). doi:10.3390/w9110868.

- "Santorini: Bottled drinking water". ekathimerini. July 30, 2003. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- "Desalination Deva Thira". DEYA Thira. 2020. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- Zolotas, Dimitris (1 September 2016). "Νέο εργοστάσιο αφαλάτωσης στη Σαντορίνη (New desalination plant in Santorini)". Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Προχωρά η αφαλάτωση στον Έξω Γιαλό Φηρών Σαντορίνης (Desalination is proceeding in Exo Gialos, Fira, Santorini)". Cyclades 24. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Summer Lovers". Reelstreets. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 2 Filming Locations". TripSavvy. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "Nolwenn Leroy - Mystère". Lyrics.com.

- "Santorini Film Festival". FilmFreeway. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Here's What Greeks Think of Rick Ross' "Santorini Greece" Music Video". The Culture Trip. 20 September 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "How to start The Fate of Atlantis Assassin's Creed Odyssey DLC". VG 24/7. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- "Places From Pokémon You May Already Know From The Real World". The Odyssey. 18 July 2016. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- Miller, David (March 2, 2017). "Spin Master Taking On Santorini and 5-Minute Dungeon for Push in to Hobby Market". Purple Pawn. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

Bibliography

- Forsyth, Phyllis Y.: Thera in the Bronze Age, Peter Lang Pub Inc, New York 1997. ISBN 0-8204-4889-3

- Friedrich, W., Fire in the Sea: the Santorini Volcano: Natural History and the Legend of Atlantis, translated by Alexander R. McBirney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- History Channel's "Lost Worlds: Atlantis" archeology series. Features scientists Dr J. Alexander MacGillivray (archeologist), Dr Colin F. MacDonald (archaeologist), Professor Floyd McCoy (vulcanologist), Professor Clairy Palyvou (architect), Nahid Humbetli (geologist) and Dr Gerassimos Papadopoulos (seismologist)

Further reading

- Bond, A. and Sparks, R. S. J. (1976). "The Minoan eruption of Santorini, Greece". Journal of the Geological Society of London, Vol. 132, 1–16.

- Doumas, C. (1983). Thera: Pompeii of the ancient Aegean. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Pichler, H. and Friedrich, W.L. (1980). "Mechanism of the Minoan eruption of Santorini". Doumas, C. Papers and Proceedings of the Second International Scientific Congress on Thera and the Aegean World II.

External links

- 5:12 | A documentary about the 1956 earthquake in Santorini.

- TheraFoundation.org, The Eruption of Thera: Date and Implications

- Santorini.gr, Thira (Santorini) Municipality Official WebSite

- CGS.Illinois.edu , Was the Bronze Age Volcanic Eruption of Thira (Santorini) a Megacatastrophe? A Geological/Archeological Detective Story, Grant Heiken, Independent consultant, author, geologist (retired) Los Alamos National Laboratory; lecture presented at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, sponsored by CGS.Illinois.edu, Center for Global Studies and CAS.UIUC.edu Archived 2016-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Advanced Study

- NewAdvent.org, Thera (Santorin) – Catholic Encyclopedia article

- URI.edu: Santorini Eruption much larger than previously thought

- Moving Postcards: Santorini Archived 2020-08-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Older eruption history at Santorini

- Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants and Bang Bang: Santorini In Pop Culture

- The castles of Santorini Archived 2020-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Photos of Santorini

- The sacred Rock Le Rocher sacré (Santorin)