Milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digest solid food.[1] Immune factors and immune-modulating components in milk contribute to milk immunity. Early-lactation milk, which is called colostrum, contains antibodies that strengthen the immune system and thus reduce the risk of many diseases. Milk contains many nutrients, including protein and lactose.[2]

.jpg.webp)

As an agricultural product, dairy milk is collected from farm animals. In 2011, dairy farms produced around 730 million tonnes (800 million short tons) of milk[3] from 260 million dairy cows.[4] India is the world's largest producer of milk and the leading exporter of skimmed milk powder, but it exports few other milk products.[5][6] Because there is an ever-increasing demand for dairy products in India, it could eventually become a net importer of dairy products.[7] New Zealand, Germany, and the Netherlands are the largest exporters of milk products.[8] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that children over the age of 12 months should have two servings of dairy milk products a day.[9]

More than six billion people worldwide consume milk and milk products, and between 750 and 900 million people live in dairy-farming households.[10]

Etymology and terminology

The term milk comes from "Old English meoluc (West Saxon), milc (Anglian), from Proto-Germanic *meluks "milk" (source also of Old Norse mjolk, Old Frisian melok, Old Saxon miluk, Dutch melk, Old High German miluh, German Milch, Gothic miluks)".[11]

Since 1961, the term milk has been defined under Codex Alimentarius standards as "the normal mammary secretion of milking animals obtained from one or more milkings without either addition to it or extraction from it, intended for consumption as liquid milk or for further processing."[12] The term dairy refers to animal milk and animal milk production.

Types of consumption

There are two distinct categories of milk consumption: all infant mammals drink milk directly from their mothers' bodies, and it is their primary source of nutrition; and humans obtain milk from other mammals for consumption by humans of all ages, as one component of a varied diet.

Nutrition for infant mammals

In almost all mammals, milk is fed to infants through breastfeeding, either directly or by expressing the milk to be stored and consumed later. The early milk from mammals is called colostrum. Colostrum contains antibodies that provide protection to the newborn baby as well as nutrients and growth factors.[13] The makeup of the colostrum and the period of secretion varies from species to species.[14]

For humans, the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for six months and breastfeeding in addition to other food for up to two years of age or more.[15] In some cultures it is common to breastfeed children for three to five years, and the period may be longer.[16]

Fresh goats' milk is sometimes substituted for breast milk, which introduces the risk of the child developing electrolyte imbalances, metabolic acidosis, megaloblastic anemia, and a host of allergic reactions.[17]

Food product for humans

In many cultures, especially in the West, humans continue to consume milk beyond infancy, using the milk of other mammals (especially cattle, goats and sheep) as a food product. Initially, the ability to digest milk was limited to children as adults did not produce lactase, an enzyme necessary for digesting the lactose in milk. People therefore converted milk to curd, cheese, and other products to reduce the levels of lactose. Thousands of years ago, a chance mutation spread in human populations in northwestern Europe that enabled the production of lactase in adulthood. This mutation allowed milk to be used as a new source of nutrition which could sustain populations when other food sources failed.[18] Milk is processed into a variety of products such as cream, butter, yogurt, kefir, ice cream, and cheese. Modern industrial processes use milk to produce casein, whey protein, lactose, condensed milk, powdered milk, and many other food-additives and industrial products.

Whole milk, butter, and cream have high levels of saturated fat.[19][20] The sugar lactose is found only in milk, and possibly in forsythia flowers and a few tropical shrubs.[21] Lactase, the enzyme needed to digest lactose, reaches its highest levels in the human small intestine immediately after birth, and then begins a slow decline unless milk is consumed regularly.[22] Those groups who continue to tolerate milk have often exercised great creativity in using the milk of domesticated ungulates, not only cattle, but also sheep, goats, yaks, water buffalo, horses, reindeer and camels. India is the largest producer and consumer of cattle milk and buffalo milk in the world.[23]

| Country | Milk (liters) | Cheese (kg) | Butter (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 135.6 | 6.7 | 2.4 | |

| 127.0 | 22.5 | 4.1 | |

| 105.9 | 10.9 | 3.0 | |

| 105.3 | 11.7 | 4.0 | |

| 90.1 | 19.1 | 1.7 | |

| 78.4 | 12.3 | 2.5 | |

| 75.8 | 15.1 | 2.8 | |

| 62.8 | 17.1 | 3.6 | |

| 55.7 | 3.6 | 0.4 | |

| 55.5 | 26.3 | 7.5 | |

| 54.2 | 21.8 | 2.3 | |

| 51.8 | 22.9 | 5.9 | |

| 49.1 | 23.4 | 0.7 | |

| 47.5 | 19.4 | 3.3 | |

| 39.5 | – | 3.5 | |

| 9.1 | – | 0.1 |

History

Humans first learned to consume the milk of other mammals regularly following the domestication of animals during the Neolithic Revolution or the development of agriculture. This development occurred independently in several global locations from as early as 9000–7000 BC in Mesopotamia[25] to 3500–3000 BC in the Americas.[26] People first domesticated the most important dairy animals – cattle, sheep and goats – in Southwest Asia, although domestic cattle had been independently derived from wild aurochs populations several times since.[27] Initially animals were kept for meat, and archaeologist Andrew Sherratt has suggested that dairying, along with the exploitation of domestic animals for hair and labor, began much later in a separate secondary products revolution in the fourth millennium BC.[28] Sherratt's model is not supported by recent findings, based on the analysis of lipid residue in prehistoric pottery, that shows that dairying was practiced in the early phases of agriculture in Southwest Asia, by at least the seventh millennium BC.[29][30]

From Southwest Asia domestic dairy animals spread to Europe (beginning around 7000 BC but did not reach Britain and Scandinavia until after 4000 BC),[31] and South Asia (7000–5500 BC).[32] The first farmers in central Europe[33] and Britain[34] milked their animals. Pastoral and pastoral nomadic economies, which rely predominantly or exclusively on domestic animals and their products rather than crop farming, were developed as European farmers moved into the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the fourth millennium BC, and subsequently spread across much of the Eurasian steppe.[35] Sheep and goats were introduced to Africa from Southwest Asia, but African cattle may have been independently domesticated around 7000–6000 BC.[36] Camels, domesticated in central Arabia in the fourth millennium BC, have also been used as dairy animals in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula.[37] The earliest Egyptian records of burn treatments describe burn dressings using milk from mothers of male babies.[38] In the rest of the world (i.e., East and Southeast Asia, the Americas and Australia), milk and dairy products were historically not a large part of the diet, either because they remained populated by hunter-gatherers who did not keep animals or the local agricultural economies did not include domesticated dairy species. Milk consumption became common in these regions comparatively recently, as a consequence of European colonialism and political domination over much of the world in the last 500 years.

In the Middle Ages, milk was called the "virtuous white liquor" because alcoholic beverages were safer to consume than the water generally available.[39] Incorrectly thought to be blood diverted from the womb to the breast, it was also known as "white blood", and treated like blood for religious dietary purposes and in humoral theory.[40]

James Rosier's record of the 1605 voyage made by George Weymouth to New England reported that the Wabanaki people Weymouth captured in Maine milked "Rain-Deere and Fallo-Deere." But Journalist Avery Yale Kamila and food historians said Rosier "misinterpreted the evidence." Historians report the Wabanaki did not domesticate deer.[41][42] The tribes of the northern woodlands have historically been making nut milk.[43] Cows were imported to New England in 1624.[44]

Industrialization

The growth in urban population, coupled with the expansion of the railway network in the mid-19th century, brought about a revolution in milk production and supply. Individual railway firms began transporting milk from rural areas to London from the 1840s and 1850s. Possibly the first such instance was in 1846, when St Thomas's Hospital in Southwark contracted with milk suppliers outside London to ship milk by rail.[45] The Great Western Railway was an early and enthusiastic adopter, and began to transport milk into London from Maidenhead in 1860, despite much criticism. By 1900, the company was transporting over 25 million imperial gallons (110 million litres; 30 million US gallons) annually.[46] The milk trade grew slowly through the 1860s, but went through a period of extensive, structural change in the 1870s and 1880s.

Urban demand began to grow, as consumer purchasing power increased and milk became regarded as a required daily commodity. Over the last three decades of the 19th century, demand for milk in most parts of the country doubled or, in some cases, tripled. Legislation in 1875 made the adulteration of milk illegal – This combined with a marketing campaign to change the image of milk. The proportion of rural imports by rail as a percentage of total milk consumption in London grew from under 5% in the 1860s to over 96% by the early 20th century. By that point, the supply system for milk was the most highly organized and integrated of any food product.[45] Milk was analyzed for infection with tuberculosis. In 1907 180 samples were tested in Birmingham and 13.3% were found to be infected.[47]

The first glass bottle packaging for milk was used in the 1870s. The first company to do so may have been the New York Dairy Company in 1877. The Express Dairy Company in England began glass bottle production in 1880. In 1884, Hervey Thatcher, an American inventor from New York, invented a glass milk bottle, called "Thatcher's Common Sense Milk Jar," which was sealed with a waxed paper disk.[48] In 1932, plastic-coated paper milk cartons were introduced commercially.[48]

In 1863, French chemist and biologist Louis Pasteur invented pasteurization, a method of killing harmful bacteria in beverages and food products.[48] He developed this method while on summer vacation in Arbois, to remedy the frequent acidity of the local wines.[49] He found out experimentally that it is sufficient to heat a young wine to only about 50–60 °C (122–140 °F) for a brief time to kill the microbes, and that the wine could be nevertheless properly aged without sacrificing the final quality.[49] In honor of Pasteur, the process became known as "pasteurization". Pasteurization was originally used as a way of preventing wine and beer from souring.[50] Commercial pasteurizing equipment was produced in Germany in the 1880s, and producers adopted the process in Copenhagen and Stockholm by 1885.[51][52]

Sources

The females of all mammal species can, by definition, produce milk, but cow's milk dominates commercial production. In 2011, FAO estimates 85% of all milk worldwide was produced from cows.[53] Human milk is not produced or distributed industrially or commercially; however, human milk banks collect donated human breastmilk and redistribute it to infants who may benefit from human milk for various reasons (premature neonates, babies with allergies, metabolic diseases, etc.) but who cannot breastfeed.[54]

In the Western world, cow's milk is produced on an industrial scale and is, by far, the most commonly consumed form of milk. Commercial dairy farming using automated milking equipment produces the vast majority of milk in developed countries. Dairy cattle, such as the Holstein, have been bred selectively for increased milk production. About 90% of the dairy cows in the United States and 85% in Great Britain are Holsteins.[22] Other dairy cows in the United States include Ayrshire, Brown Swiss, Guernsey, Jersey and Milking Shorthorn (Dairy Shorthorn).

Other animal-based sources

Aside from cattle, many kinds of livestock provide milk used by humans for dairy products. These animals include water buffalo, goat, sheep, camel, donkey, horse, reindeer and yak. The first four respectively produced about 11%, 2%, 1.4% and 0.2% of all milk worldwide in 2011.[53]

In Russia and Sweden, small moose dairies also exist.[55]

According to the US National Bison Association, American bison (also called American buffalo) are not milked commercially;[56] however, various sources report cows resulting from cross-breeding bison and domestic cattle are good milk producers, and have been used both during the European settlement of North America[57] and during the development of commercial Beefalo in the 1970s and 1980s.[58]

Swine are almost never milked, even though their milk is similar to cow's milk and perfectly suitable for human consumption. The main reasons for this are that milking a sow's numerous small teats is very cumbersome, and that sows cannot store their milk as cows can.[59] A few pig farms do sell pig cheese as a novelty item; these cheeses are exceedingly expensive.[60]

Production worldwide

| Rank | Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 186,143,000 | |

| – | 167,256,000 | |

| 2 | 98,646,000 | |

| 3 | 45,623,000 | |

| 4 | 35,539,000 | |

| 5 | 31,592,000 | |

| 6 | 31,527,000 | |

| 7 | 22,791,000 | |

| 8 | 21,372,000 | |

| World | 842,989,000 | |

| Rank | Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 101,251,009 | |

| 2 | 87,822,387 | |

| 3 | 36,508,411 | |

| 4 | 34,400,000 | |

| 5 | 33,164,910 | |

| 6 | 31,959,801 | |

| 7 | 25,147,310 | |

| 8 | 22,508,000 | |

| 9 | 21,871,305 | |

| 10 | 20,000,000 |

| Rank | Country | Production (metric tons) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,888,077 | |

| 2 | 2,671,911 | |

| 3 | 1,165,043 | |

| 4 | 965,000 | |

| 5 | 679,300 | |

| 6 | 554,143 | |

| 7 | 523,900 | |

| 8 | 467,148 | |

| 9 | 407,346 | |

| 10 | 407,000 |

In 2012, the largest producer of milk and milk products was India, followed by the United States of America, China, Pakistan and Brazil.[66] All 28 European Union members together produced 153.8 million tonnes (169.5 million short tons) of milk in 2013, the largest by any politico-economic union.[67]

Increasing affluence in developing countries, as well as increased promotion of milk and milk products, has led to a rise in milk consumption in developing countries in recent years. In turn, the opportunities presented by these growing markets have attracted investments by multinational dairy firms. Nevertheless, in many countries production remains on a small scale and presents significant opportunities for diversification of income sources by small farms.[68] Local milk collection centers, where milk is collected and chilled prior to being transferred to urban dairies, are a good example of where farmers have been able to work on a cooperative basis, particularly in countries such as India.[69]

Production yields

FAO reports[53] Israel dairy farms are the most productive in the world, with a yield of 12,546 kilograms (27,659 lb) milk per cow per year. This survey over 2001 and 2007 was conducted by ICAR (International Committee for Animal Recording)[70] across 17 developed countries. The survey found that the average herd size in these developed countries increased from 74 to 99 cows per herd between 2001 and 2007. A dairy farm had an average of 19 cows per herd in Norway, and 337 in New Zealand. Annual milk production in the same period increased from 7,726 to 8,550 kg (17,033 to 18,850 lb) per cow in these developed countries. The lowest average production was in New Zealand at 3,974 kg (8,761 lb) per cow. The milk yield per cow depended on production systems, nutrition of the cows, and only to a minor extent different genetic potential of the animals. What the cow ate made the most impact on the production obtained. New Zealand cows with the lowest yield per year grazed all year, in contrast to Israel with the highest yield where the cows ate in barns with an energy-rich mixed diet.

The milk yield per cow in the United States was 9,954 kg (21,945 lb) per year in 2010. In contrast, the milk yields per cow in India and China – the second and third largest producers – were respectively 1,154 kg (2,544 lb) and 2,282 kg (5,031 lb) per year.[71]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report mentions the possibility that the already recorded stagnation of dairy production in both China and West Africa can be attributed to persistent increases in heat stress caused by climate change.[72]: 747 This is a plausible hypothesis, because even mild heat stress can reduce daily yields: research in Sweden found that average daily temperatures of 20–25 °C (68–77 °F) reduce daily milk yield per cow by 0.2 kg, with the loss reaching 0.54 kg for 25–30 °C (77–86 °F).[73] Research in a humid tropical climate describes a more linear relationship, with every unit of heat stress reducing yield by 2.13%.[74] In the intensive farming systems, daily milk yield per cow declines by 1.8 kg during severe heat stress. In organic farming systems, the effect of heat stress on milk yields is limited, but milk quality suffers substantially, with lower fat and protein content.[75] In China, daily milk production per cow is already lower than the average by between 0.7 and 4 kg in July (the hottest month of the year), and by 2070, it may decline by up to 50% (or 7.2 kg) due to climate change.[76] Heatwaves can also reduce milk yield, with particularly acute impacts if the heatwave lasts for four or more days, as at that point the cow's thermoregulation capacity is usually exhausted, and its core body temperature starts to increase.[77]

Price

It was reported in 2007 that with increased worldwide prosperity and the competition of bio-fuel production for feed stocks, both the demand for and the price of milk had substantially increased worldwide. Particularly notable was the rapid increase of consumption of milk in China and the rise of the price of milk in the United States above the government subsidized price.[78] In 2010 the Department of Agriculture predicted farmers would receive an average of $1.35 per US gallon ($0.36/L; $1.62/imp gal) of cow's milk, which is down 30 cents per US gallon (7.9 ¢/L; 36 ¢/imp gal) from 2007 and below the break-even point for many cattle farmers.[79]

Composition

Milk is an emulsion or colloid of butterfat globules within a water-based fluid that contains dissolved carbohydrates and protein aggregates with minerals.[80] Because it is produced as a food source for the young, all of its contents provide benefits for growth. The principal requirements are energy (lipids, lactose, and protein), biosynthesis of non-essential amino acids supplied by proteins (essential amino acids and amino groups), essential fatty acids, vitamins and inorganic elements, and water.[81]

pH

The pH of cow's milk, ranging from 6.7 to 6.9, is similar to other bovines and non-bovine mammals.[82]

Lipids

Initially milk fat is secreted in the form of a fat globule surrounded by a membrane.[83] Each fat globule is composed almost entirely of triacylglycerols and is surrounded by a membrane consisting of complex lipids such as phospholipids, along with proteins. These act as emulsifiers which keep the individual globules from coalescing and protect the contents of these globules from various enzymes in the fluid portion of the milk. Although 97–98% of lipids are triacylglycerols, small amounts of di- and monoacylglycerols, free cholesterol and cholesterol esters, free fatty acids, and phospholipids are also present. Unlike protein and carbohydrates, fat composition in milk varies widely due to genetic, lactational, and nutritional factor difference between different species.[83]

Fat globules vary in size from less than 0.2 to about 15 micrometers in diameter between different species. Diameter may also vary between animals within a species and at different times within a milking of a single animal. In unhomogenized cow's milk, the fat globules have an average diameter of two to four micrometers and with homogenization, average around 0.4 micrometers.[83] The fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K along with essential fatty acids such as linoleic and linolenic acid are found within the milk fat portion of the milk.[22]

| Fatty acid | length | mol% (rounded) |

|---|---|---|

| Butyryl | C4 | 12 |

| Myristyl | C14 | 11 |

| Palmityl | C16 | 24 |

| Oleyl | C18:1 | 24 |

Proteins

Normal bovine milk contains 30–35 grams of protein per liter, of which about 80% is arranged in casein micelles. Total proteins in milk represent 3.2% of its composition (nutrition table).

Caseins

The largest structures in the fluid portion of the milk are "casein micelles": aggregates of several thousand protein molecules with superficial resemblance to a surfactant micelle, bonded with the help of nanometer-scale particles of calcium phosphate. Each casein micelle is roughly spherical and about a tenth of a micrometer across. There are four different types of casein proteins: αs1-, αs2-, β-, and κ-caseins. Most of the casein proteins are bound into the micelles. There are several competing theories regarding the precise structure of the micelles, but they share one important feature: the outermost layer consists of strands of one type of protein, k-casein, reaching out from the body of the micelle into the surrounding fluid. These kappa-casein molecules all have a negative electrical charge and therefore repel each other, keeping the micelles separated under normal conditions and in a stable colloidal suspension in the water-based surrounding fluid.[22][85]

Milk contains dozens of other types of proteins beside caseins and including enzymes. These other proteins are more water-soluble than caseins and do not form larger structures. Because the proteins remain suspended in whey, remaining when caseins coagulate into curds, they are collectively known as whey proteins. Lactoglobulin is the most common whey protein by a large margin.[22] The ratio of caseins to whey proteins varies greatly between species; for example, it is 82:18 in cows and around 32:68 in humans.[86]

| Species | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Human | 29.7:70.3 – 33.7:66.3 |

| Bovine | 82:18 |

| Caprine | 78:22 |

| Ovine | 76:24 |

| Buffalo | 82:18 |

| Equine | 52:48 |

| Camel | 73:27 – 76:24 |

| Yak | 82:18 |

| Reindeer | 80:20 – 83:17 |

Salts, minerals, and vitamins

Bovine milk contains a variety of cations and anions traditionally referred to as "minerals" or "milk salts". Calcium, phosphate, magnesium, sodium, potassium, citrate, and chloride are all included and they typically occur at concentrations of 5–40 mM. The milk salts strongly interact with casein, most notably calcium phosphate. It is present in excess and often, much greater excess of solubility of solid calcium phosphate.[81] In addition to calcium, milk is a good source of many other vitamins. Vitamins A, B6, B12, C, D, K, E, thiamine, niacin, biotin, riboflavin, folates, and pantothenic acid are all present in milk.

Calcium phosphate structure

For many years the most widely accepted theory of the structure of a micelle was that it was composed of spherical casein aggregates, called submicelles, that were held together by calcium phosphate linkages. However, there are two recent models of the casein micelle that refute the distinct micellular structures within the micelle.

The first theory, attributed to de Kruif and Holt, proposes that nanoclusters of calcium phosphate and the phosphopeptide fraction of beta-casein are the centerpiece to micellar structure. Specifically in this view unstructured proteins organize around the calcium phosphate, giving rise to their structure, and thus no specific structure is formed.

Under the second theory, proposed by Horne, the growth of calcium phosphate nanoclusters begins the process of micelle formation, but is limited by binding phosphopeptide loop regions of the caseins. Once bound, protein-protein interactions are formed and polymerization occurs, in which K-casein is used as an end cap to form micelles with trapped calcium phosphate nanoclusters.

Some sources indicate that the trapped calcium phosphate is in the form of Ca9(PO4)6; whereas others say it is similar to the structure of the mineral brushite, CaHPO4·2H2O.[87]

Sugars and carbohydrates

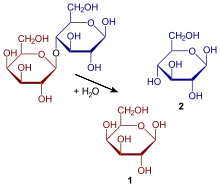

Milk contains several different carbohydrates, including lactose, glucose, galactose, and other oligosaccharides. The lactose gives milk its sweet taste and contributes approximately 40% of the calories in whole cow's milk's. Lactose is a disaccharide composite of two simple sugars, glucose and galactose. Bovine milk averages 4.8% anhydrous lactose, which amounts to about 50% of the total solids of skimmed milk. Levels of lactose are dependent upon the type of milk as other carbohydrates can be present at higher concentrations than lactose in milks.[81]

Miscellaneous contents

Other components found in raw cow's milk are living white blood cells, mammary gland cells, various bacteria, vitamin C, and a large number of active enzymes.[22]

Appearance

Both the fat globules and the smaller casein micelles, which are just large enough to deflect light, contribute to the opaque white color of milk. The fat globules contain some yellow-orange carotene, enough in some breeds (such as Guernsey and Jersey cattle) to impart a golden or "creamy" hue to a glass of milk. The riboflavin in the whey portion of milk has a greenish color, which sometimes can be discerned in skimmed milk or whey products.[22] Fat-free skimmed milk has only the casein micelles to scatter light, and they tend to scatter shorter-wavelength blue light more than they do red, giving skimmed milk a bluish tint.[85]

Processing

In most Western countries, centralized dairy facilities process milk and products obtained from milk, such as cream, butter, and cheese. In the US, these dairies usually are local companies, while in the Southern Hemisphere facilities may be run by large multi-national corporations such as Fonterra.

Pasteurization

Pasteurization is used to kill harmful pathogenic bacteria such as M. paratuberculosis and E. coli 0157:H7 by heating the milk for a short time and then immediately cooling it.[88] Types of pasteurized milk include full cream, reduced fat, skim milk, calcium enriched, flavored, and UHT.[89] The standard high temperature short time (HTST) process of 72 °C (162 °F) for 15 seconds completely kills pathogenic bacteria in milk,[90] rendering it safe to drink for up to three weeks if continually refrigerated.[91] Dairies print best before dates on each container, after which stores remove any unsold milk from their shelves.

A side effect of the heating of pasteurization is that some vitamin and mineral content is lost. Soluble calcium and phosphorus decrease by 5%, thiamin and vitamin B12 by 10%, and vitamin C by 20% or greater (even to complete loss).[92] Because losses are small in comparison to the large amount of the two B-vitamins present, milk continues to provide significant amounts of thiamin and vitamin B12. The loss of vitamin C is not nutritionally significant in a well-balanced diet, as milk is not an important dietary source of vitamin C.

Filtration

Microfiltration is a process that partially replaces pasteurization and produces milk with fewer microorganisms and longer shelf life without a change in the taste of the milk. In this process, cream is separated from the skimmed milk and is pasteurized in the usual way, but the skimmed milk is forced through ceramic microfilters that trap 99.9% of microorganisms in the milk[93] (as compared to 99.999% killing of microorganisms in standard HTST pasteurization).[94] The skimmed milk then is recombined with the pasteurized cream to reconstitute the original milk composition.

Ultrafiltration uses finer filters than microfiltration, which allow lactose and water to pass through while retaining fats, calcium and protein.[95] As with microfiltration, the fat may be removed before filtration and added back in afterwards.[96] Ultrafiltered milk is used in cheesemaking, since it has reduced volume for a given protein content, and is sold directly to consumers as a higher protein, lower sugar content, and creamier alternative to regular milk.[97]

Creaming and homogenization

Upon standing for 12 to 24 hours, fresh milk has a tendency to separate into a high-fat cream layer on top of a larger, low-fat milk layer. The cream often is sold as a separate product with its own uses. Today the separation of the cream from the milk usually is accomplished rapidly in centrifugal cream separators. The fat globules rise to the top of a container of milk because fat is less dense than water.[22]

The smaller the globules, the more other molecular-level forces prevent this from happening. The cream rises in cow's milk much more quickly than a simple model would predict: rather than isolated globules, the fat in the milk tends to form into clusters containing about a million globules, held together by a number of minor whey proteins.[22] These clusters rise faster than individual globules can. The fat globules in milk from goats, sheep, and water buffalo do not form clusters as readily and are smaller to begin with, resulting in a slower separation of cream from these milks.[22]

Milk often is homogenized, a treatment that prevents a cream layer from separating out of the milk. The milk is pumped at high pressures through very narrow tubes, breaking up the fat globules through turbulence and cavitation.[98] A greater number of smaller particles possess more total surface area than a smaller number of larger ones, and the original fat globule membranes cannot completely cover them. Casein micelles are attracted to the newly exposed fat surfaces.

Nearly one-third of the micelles in the milk end up participating in this new membrane structure. The casein weighs down the globules and interferes with the clustering that accelerated separation. The exposed fat globules are vulnerable to certain enzymes present in milk, which could break down the fats and produce rancid flavors. To prevent this, the enzymes are inactivated by pasteurizing the milk immediately before or during homogenization.

Homogenized milk tastes blander but feels creamier in the mouth than unhomogenized. It is whiter and more resistant to developing off flavors.[22] Creamline (or cream-top) milk is unhomogenized. It may or may not have been pasteurized. Milk that has undergone high-pressure homogenization, sometimes labeled as "ultra-homogenized", has a longer shelf life than milk that has undergone ordinary homogenization at lower pressures.[99]

UHT

Ultra Heat Treatment (UHT) is a type of milk processing where all bacteria are destroyed with high heat to extend its shelf life for up to 6 months, as long as the package is not opened. Milk is firstly homogenized and then is heated to 138 degrees Celsius for 2–4 seconds. The milk is immediately cooled down and packed into a sterile container. As a result of this treatment, all the pathogenic bacteria within the milk are destroyed, unlike when the milk is just pasteurized. The treated milk will keep for up to 6 months if unopened. UHT milk does not need to be refrigerated until the package is opened, which makes it easier to ship and store. However, in this process there is a loss of vitamin B1 and vitamin C, and there is also a slight change in the taste of the milk.[100]

Nutrition and health

The composition of milk differs widely among species. Factors such as the type of protein; the proportion of protein, fat, and sugar; the levels of various vitamins and minerals; and the size of the butterfat globules, and the strength of the curd are among those that may vary.[24] For example:

- Human milk contains, on average, 1.1% protein, 4.2% fat, 7.0% lactose (a sugar), and supplies 72 kcal of energy per 100 grams.

- Cow's milk contains, on average, 3.4% protein, 3.6% fat, and 4.6% lactose, 0.7% minerals[101] and supplies 66 kcal of energy per 100 grams. See also Nutritional value further on in this article and more complete lists at online sources that list values and differences in categories.[102]

Donkey and horse milk have the lowest fat content, while the milk of seals and whales may contain more than 50% fat.[103]

| Constituents | Unit | Cow | Goat | Sheep | Water buffalo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | g | 87.8 | 88.9 | 83.0 | 81.1 |

| Protein | g | 3.2 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| Fat | g | 3.9 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 8.0 |

| ----Saturated fatty acids | g | 2.4 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 4.2 |

| ----Monounsaturated fatty acids | g | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| ----Polyunsaturated fatty acids | g | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Carbohydrate (i.e. the sugar form of lactose) | g | 4.8 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Cholesterol | mg | 14 | 10 | 11 | 8 |

| Calcium | mg | 120 | 100 | 170 | 195 |

| Energy | kcal | 66 | 60 | 95 | 110 |

| kJ | 275 | 253 | 396 | 463 |

Cow's milk: variation by breed

These compositions vary by breed, animal, and point in the lactation period.

| Cow breed | Approximate percentage |

|---|---|

| Jersey | 5.2 |

| Zebu | 4.7 |

| Brown Swiss | 4.0 |

| Holstein-Friesian | 3.6 |

The protein range for these four breeds is 3.3% to 3.9%, while the lactose range is 4.7% to 4.9%.[22]

Milk fat percentages may be manipulated by dairy farmers' stock diet formulation strategies. The infection known as mastitis, especially in dairy cattle, can cause fat levels to decline.[104]

Nutritional value

Processed cow's milk was formulated to contain differing amounts of fat during the 1950s. One cup (250 mL) of 2%-fat cow's milk contains 285 mg of calcium, which represents 22% to 29% of the daily recommended intake (DRI) of calcium for an adult. Depending on its age, milk contains 8 grams of protein, and a number of other nutrients (either naturally or through fortification).

Whole milk has a glycemic index of 39±3.[105] A food is considered to have a low GI if it is 55 or less.

For protein quality, whole milk has a Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) of 1.43, with the limiting amino acid for those groups being methionine and cysteine.[106] A DIAAS of 1 or more is considered to be an excellent/high protein quality source.[107]

Allergy

One of the most common food allergies in infants is to cow's milk. This is an immunologically mediated adverse reaction, rarely fatal, to one or more cow's milk proteins.[108] Milk allergy affects between 2% and 3% of babies and young children.[109] To reduce risk, recommendations are that babies should be exclusively breastfed for at least four months, preferably six months, before introducing cow's milk.[110] The majority of children outgrow milk allergy, but for about 0.4% the condition persists into adulthood.[111]

Lactose intolerance

Lactose intolerance is a condition in which people have symptoms due to deficiency or absence of the enzyme lactase in the small intestine, causing poor absorption of milk lactose.[112][113] People affected vary in the amount of lactose they can tolerate before symptoms develop,[112] which may include abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, gas, and nausea.[112] Severity depends on the amount of milk consumed.[112] Those affected are usually able to drink at least one cup of milk without developing significant symptoms, with greater amounts tolerated if drunk with a meal or throughout the day.[112][114]

Evolution of lactation

The mammary gland is thought to have derived from apocrine skin glands.[115] It has been suggested that the original function of lactation (milk production) was keeping eggs moist. Much of the argument is based on monotremes (egg-laying mammals).[115][116][117] The original adaptive significance of milk secretions may have been nutrition[118] and immunological protection.[119][120][121][122].

Tritylodontid cynodonts seem to have displayed lactation, based on their dental replacement patterns.[123]

Bovine growth hormone supplementation

Since November 1993, recombinant bovine somatotropin (rbST), also called rBGH, has been sold to dairy farmers with FDA approval. Cows produce bovine growth hormone naturally, but some producers administer an additional recombinant version of BGH which is produced through genetically engineered E. coli to increase milk production. Bovine growth hormone also stimulates liver production of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1). The US Food and Drug Administration,[124] the National Institutes of Health[125] and the World Health Organization[126] have reported that both of these compounds are safe for human consumption at the amounts present.

Milk from cows given rBST may be sold in the United States, and the FDA stated that no significant difference has been shown between milk derived from rBST-treated and that from non-rBST-treated cows.[127] Milk that advertises that it comes from cows not treated with rBST, is required to state this finding on its label.

Cows receiving rBGH supplements may more frequently contract an udder infection known as mastitis.[128] Problems with mastitis have led to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan banning milk from rBST treated cows. Mastitis, among other diseases, may be responsible for the fact that levels of white blood cells in milk vary naturally.[129][130]

rBGH is also banned in the European Union, for reasons of animal welfare.[131]

Varieties and brands

Milk products are sold in a number of varieties based on types/degrees of:

- additives (e.g. vitamins, flavorings)

- age (e.g. cheddar, old cheddar)

- coagulation (e.g. cottage cheese)

- farming method (e.g. organic, grass-fed, haymilk)

- fat content (e.g. half and half, 3% fat milk, 2% milk, 1% milk, skim milk)

- fermentation (e.g. buttermilk)

- flavoring (e.g. chocolate and strawberry)

- homogenization (e.g. cream top)

- packaging (e.g. bottle, carton, bag)

- pasteurization (e.g. raw milk, pasteurized milk)

- reduction or elimination of lactose

- species (e.g. cow, goat, sheep)

- sweetening (e.g., chocolate and strawberry milk)

- water content (e.g. dry milk powder, condensed milk, ultrafiltered milk)

Milk preserved by the UHT process does not need to be refrigerated before opening and has a much longer shelf life (six months) than milk in ordinary packaging. It is typically sold unrefrigerated in the UK, US, Europe, Latin America, and Australia.

Reduction or elimination of lactose

Lactose-free milk can be produced by passing milk over lactase enzyme bound to an inert carrier. Once the molecule is cleaved, there are no lactose ill effects. Forms are available with reduced amounts of lactose (typically 30% of normal), and alternatively with nearly 0%. The only noticeable difference from regular milk is a slightly sweeter taste due to the cleavage of lactose into glucose and galactose. Lactose-reduced milk can also be produced via ultra filtration, which removes smaller molecules such as lactose and water while leaving calcium and proteins behind. Milk produced via these methods has a lower sugar content than regular milk.[95] To aid digestion in those with lactose intolerance, another alternative is dairy foods, milk and yogurt, with added bacterial cultures such as Lactobacillus acidophilus ("acidophilus milk") and bifidobacteria.[132] Another milk with Lactococcus lactis bacteria cultures ("cultured buttermilk") often is used in cooking to replace the traditional use of naturally soured milk, which has become rare due to the ubiquity of pasteurization, which also kills the naturally occurring Lactococcus bacteria.[133]

Additives and flavoring

Commercially sold milk commonly has vitamin D added to it to make up for lack of exposure to UVB radiation. Reduced-fat milks often have added vitamin A palmitate to compensate for the loss of the vitamin during fat removal; in the United States this results in reduced fat milks having a higher vitamin A content than whole milk.[134] Milk often has flavoring added to it for better taste or as a means of improving sales. Chocolate milk has been sold for many years and has been followed more recently by strawberry milk and others. Some nutritionists have criticized flavored milk for adding sugar, usually in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, to the diets of children who are already commonly obese in the US.[135]

Distribution

Due to the short shelf life of normal milk, it used to be delivered to households daily in many countries; however, improved refrigeration at home, changing food shopping patterns because of supermarkets, and the higher cost of home delivery mean that daily deliveries by a milkman are no longer available in most countries.

Australia and New Zealand

In Australia and New Zealand, prior to metrication, milk was generally distributed in 1 pint (568 mL) glass bottles. In Australia and Ireland there was a government funded "free milk for school children" program, and milk was distributed at morning recess in 1/3 pint bottles. With the conversion to metric measures, the milk industry was concerned that the replacement of the pint bottles with 500 mL bottles would result in a 13.6% drop in milk consumption; hence, all pint bottles were recalled and replaced by 600 mL bottles. With time, due to the steadily increasing cost of collecting, transporting, storing and cleaning glass bottles, they were replaced by cardboard cartons. A number of designs were used, including a tetrahedron which could be close-packed without waste space, and could not be knocked over accidentally (slogan: "No more crying over spilt milk"). However, the industry eventually settled on a design similar to that used in the United States.[136]

Milk is now available in a variety of sizes in paperboard milk cartons (250 mL, 375 mL, 600 mL, 1 liter and 1.5 liters) and plastic bottles (1, 2 and 3 liters). A significant addition to the marketplace has been "long-life" milk (UHT), generally available in 1 and 2 liter rectangular cardboard cartons. In urban and suburban areas where there is sufficient demand, home delivery is still available, though in suburban areas this is often 3 times per week rather than daily. Another significant and popular addition to the marketplace has been flavored milks; for example, as mentioned above, Farmers Union Iced Coffee outsells Coca-Cola in South Australia.[137]

India

In rural India, milk is home delivered, daily, by local milkmen carrying bulk quantities in a metal container, usually on a bicycle. In other parts of metropolitan India, milk is usually bought or delivered in plastic bags or cartons via shops or supermarkets.

The current milk chain flow in India is from milk producer to milk collection agent. Then it is transported to a milk chilling center and bulk transported to the processing plant, then to the sales agent and finally to the consumer.

A 2011 survey by the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India found that nearly 70% of samples had not conformed to the standards set for milk. The study found that due to lack of hygiene and sanitation in milk handling and packaging, detergents (used during cleaning operations) were not washed properly and found their way into the milk. About 8% of samples in the survey were found to have detergents, which are hazardous to health.[138]

Pakistan

In Pakistan, milk is supplied in jugs. Milk has been a staple food, especially among the pastoral tribes in this country.

United Kingdom

Since the late 1990s, milk-buying patterns have changed drastically in the UK. The classic milkman, who travels his local milk round (route) using a milk float (often battery powered) during the early hours and delivers milk in 1-pint glass bottles with aluminum foil tops directly to households, has almost disappeared. Two of the main reasons for the decline of UK home deliveries by milkmen are household refrigerators (which lessen the need for daily milk deliveries) and private car usage (which has increased supermarket shopping). Another factor is that it is cheaper to purchase milk from a supermarket than from home delivery. In 1996, more than 2.5 billion liters of milk were still being delivered by milkmen, but by 2006 only 637 million liters (13% of milk consumed) was delivered by some 9,500 milkmen.[139] By 2010, the estimated number of milkmen had dropped to 6,000.[140] Assuming that delivery per milkman is the same as it was in 2006, this means milkmen deliveries now only account for 6–7% of all milk consumed by UK households (6.7 billion liters in 2008/2009).[141]

Almost 95% of all milk in the UK is thus sold in shops today, most of it in plastic bottles of various sizes, but some also in milk cartons. Milk is hardly ever sold in glass bottles in UK shops.

United States

In the United States, glass milk bottles have been replaced mostly with milk cartons and plastic jugs. Gallons of milk are almost always sold in jugs, while half gallons and quarts may be found in both paper cartons and plastic jugs, and smaller sizes are almost always in cartons.

The "half pint" (237 mL, 5⁄12 imp pt) milk carton is the traditional unit as a component of school lunches, though some companies have replaced that unit size with a plastic bottle, which is also available at retail in 6- and 12-pack size.

Packaging

Glass milk bottles are now rare. Most people purchase milk in bags, plastic bottles, or plastic-coated paper cartons. Ultraviolet (UV) light from fluorescent lighting can alter the flavor of milk, so many companies that once distributed milk in transparent or highly translucent containers are now using thicker materials that block the UV light. Milk comes in a variety of containers with local variants:

- Argentina

- Commonly sold in 1-liter bags and cardboard boxes. The bag is then placed in a plastic jug and the corner cut off before the milk is poured.

- Australia and New Zealand

- Distributed in a variety of sizes, most commonly in aseptic cartons for up to 1.5 liters, and plastic screw-top bottles beyond that with the following volumes; 1.1 L, 2 L, and 3 L. 1-liter milk bags are starting to appear in supermarkets, but have not yet proved popular. Most UHT-milk is packed in 1 or 2 liter paper containers with a sealed plastic spout.[136]

- Brazil

- Used to be sold in cooled 1-liter bags, just like in South Africa. Today the most common form is 1-liter aseptic cartons containing UHT skimmed, semi-skimmed or whole milk, although the plastic bags are still in use for pasteurized milk. Higher grades of pasteurized milk can be found in cartons or plastic bottles. Sizes other than 1-liter are rare.

- Canada

- 1.33 liter plastic bags (sold as 4 liters in 3 bags) are widely available in some areas (especially the Maritimes, Ontario and Quebec), although the 4 liter plastic jug has supplanted them in western Canada. Other common packaging sizes are 2 liter, 1 liter, 500 mL, and 250 mL cartons, as well as 4 liter, 1 liter, 250 mL aseptic cartons and 500 mL plastic jugs.

- Chile

- Distributed most commonly in aseptic cartons for up to 1 liter, but smaller, snack-sized cartons are also popular. The most common flavors, besides the natural presentation, are chocolate, strawberry and vanilla.

- China

- Sweetened milk is a drink popular with students of all ages and is often sold in small plastic bags complete with straw. Adults not wishing to drink at a banquet often drink milk served from cartons or milk tea.

- Colombia

- Sells milk in 1-liter plastic bags.

- Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro

- UHT milk (trajno mlijeko/trajno mleko/трајно млеко) is sold in 500 mL and 1 L (sometimes also 200 mL) aseptic cartons. Non-UHT pasteurized milk (svježe mlijeko/sveže mleko/свеже млеко) is most commonly sold in 1 L and 1.5 L PET bottles, though in Serbia one can still find milk in plastic bags.

- Estonia

- Commonly sold in 1 L bags or 0.33 L, 0.5 L, 1 L or 1.5 L cartons.

- Parts of Europe

- Sizes of 500 mL, 1 liter (the most common), 1.5 liters, 2 liters and 3 liters are commonplace.

- Finland

- Commonly sold in 1 L or 1.5 L cartons, in some places also in 2 dl and 5 dl cartons.

- Germany

- Commonly sold in 1-liter cartons. Sale in 1-liter plastic bags (common in the 1980s) is now rare.

- Hong Kong

- Milk is sold in glass bottles (220 mL), cartons (236 mL and 1 L), plastic jugs (2 liters) and aseptic cartons (250 mL).

- India

- Commonly sold in 500 mL plastic bags and in bottles in some parts like in the West. It is still customary to serve the milk boiled, despite pasteurization. Milk is often buffalo milk. Flavored milk is sold in most convenience stores in waxed cardboard containers. Convenience stores also sell many varieties of milk (such as flavored and ultra-pasteurized) in various sizes, usually in aseptic cartons.

- Indonesia

- Usually sold in 1-liter cartons, but smaller, snack-sized cartons are available.

- Italy

- Commonly sold in 1-liter cartons or bottles and less commonly in 0.5 or 0.25-liter cartons. Whole milk, semi-skimmed milk, skimmed, lactose-free, and flavored (usually in small packages) milk is available. Milk is sold fresh or UHT. Goat's milk is also available in small amounts. UHT semi-skimmed milk is the most sold, but cafés use almost exclusively fresh whole milk.

- Japan

- Commonly sold in 1-liter waxed paperboard cartons. In most city centers there is also home delivery of milk in glass jugs. As seen in China, sweetened and flavored milk drinks are commonly seen in vending machines.

- Kenya

- Milk in Kenya is mostly sold in plastic-coated aseptic paper cartons supplied in 300 mL, 500 mL or 1 liter volumes. In rural areas, milk is stored in plastic bottles or gourds.[142][143] The standard unit of measuring milk quantity in Kenya is a liter.

- Pakistan

- Milk is supplied in 500 mL plastic bags and carried in jugs from rural to cities for selling

- Philippines

- Milk is supplied in 1000 mL plastic bottles and delivered from factories to cities for selling.

- Poland

- UHT milk is mostly sold in aseptic cartons (500 mL, 1 L, 2 L), and non-UHT in 1 L plastic bags or plastic bottles. Milk, UHT is commonly boiled, despite being pasteurized.

- South Africa

- Commonly sold in 1-liter bags. The bag is then placed in a plastic jug and the corner cut off before the milk is poured.

- South Korea

- Sold in cartons (180 mL, 200 mL, 500 mL 900 mL, 1 L, 1.8 L, 2.3 L), plastic jugs (1 L and 1.8 L), aseptic cartons (180 mL and 200 mL) and plastic bags (1 L).

- Sweden

- Commonly sold in 0.3 L, 1 L or 1.5 L cartons and sometimes as plastic or glass milk bottles.

- Turkey

- Commonly sold in 500 mL or 1 L cartons or special plastic bottles. UHT milk is more popular. Milkmen also serve in smaller towns and villages.

- United Kingdom

- Most stores stock imperial sizes: 1 pint (568 mL), 2 pints (1.136 L), 4 pints (2.273 L), 6 pints (3.408 L) or a combination including both metric and imperial sizes. Glass milk bottles delivered to the doorstep by the milkman are typically pint-sized and are returned empty by the householder for repeated reuse. Milk is sold at supermarkets in either aseptic cartons or HDPE bottles. Supermarkets have also now begun to introduce milk in bags, to be poured from a proprietary jug and nozzle.

- United States

- Commonly sold in gallon (3.78 L), half-gallon (1.89 L) and quart (0.94 L) containers of natural-colored HDPE resin, or, for sizes less than one gallon, cartons of waxed paperboard. Bottles made of opaque PET are also becoming commonplace for smaller, particularly metric, sizes such as one liter. The US single-serving size is usually the half-pint (about 240 mL). Less frequently, dairies deliver milk directly to consumers, from coolers filled with glass bottles which are typically half-gallon sized and returned for reuse. Some convenience store chains in the United States (such as Kwik Trip in the Midwest) sell milk in half-gallon bags, while another rectangular cube gallon container design used for easy stacking in shipping and displaying is used by warehouse clubs such as Costco and Sam's Club, along with some Walmart stores.[144]

- Uruguay

- Pasteurized milk is commonly sold in 1-liter bags and ultra-pasteurized milk is sold in cardboard boxes called Tetra Briks. Non-pasteurized milk is forbidden. Until the 1960s no treatment was applied; milk was sold in bottles. As of 2017, plastic jugs used for pouring the bags, or "sachets", are in common use.

Practically everywhere, condensed milk and evaporated milk are distributed in metal cans, 250 and 125 mL paper containers and 100 and 200 mL squeeze tubes, and powdered milk (skim and whole) is distributed in boxes or bags.

Spoilage and fermented milk products

When raw milk is left standing for a while, it turns "sour". This is the result of fermentation, where lactic acid bacteria ferment the lactose in the milk into lactic acid. Prolonged fermentation may render the milk unpleasant to consume. This fermentation process is exploited by the introduction of bacterial cultures (e.g. Lactobacilli sp., Streptococcus sp., Leuconostoc sp., etc.) to produce a variety of fermented milk products. The reduced pH from lactic acid accumulation denatures proteins and causes the milk to undergo a variety of different transformations in appearance and texture, ranging from an aggregate to smooth consistency. Some of these products include sour cream, yogurt, cheese, buttermilk, viili, kefir, and kumis. See Dairy product for more information.

Pasteurization of cow's milk initially destroys any potential pathogens and increases the shelf life,[145][146] but eventually results in spoilage that makes it unsuitable for consumption. This causes it to assume an unpleasant odor, and the milk is deemed non-consumable due to unpleasant taste and an increased risk of food poisoning. In raw milk, the presence of lactic acid-producing bacteria, under suitable conditions, ferments the lactose present to lactic acid. The increasing acidity in turn prevents the growth of other organisms, or slows their growth significantly. During pasteurization, however, these lactic acid bacteria are mostly destroyed.

In order to prevent spoilage, milk can be kept refrigerated and stored between 1 and 4 °C (34 and 39 °F) in bulk tanks. Most milk is pasteurized by heating briefly and then refrigerated to allow transport from factory farms to local markets. The spoilage of milk can be forestalled by using ultra-high temperature (UHT) treatment. Milk so treated can be stored unrefrigerated for several months until opened but has a characteristic "cooked" taste. Condensed milk, made by removing most of the water, can be stored in cans for many years, unrefrigerated, as can evaporated milk.

Powdered milk

The most durable form of milk is powdered milk, which is produced from milk by removing almost all water. The moisture content is usually less than 5% in both drum- and spray-dried powdered milk.

Freezing of milk can cause fat globule aggregation upon thawing, resulting in milky layers and butterfat lumps. These can be dispersed again by warming and stirring the milk.[147] It can change the taste by destruction of milk-fat globule membranes, releasing oxidized flavors.[147]

Use in other food products

Milk is used to make yogurt, cheese, ice milk, pudding, hot chocolate and french toast, among many other products. Milk is often added to dry breakfast cereal, porridge and granola. Milk is mixed with ice cream and flavored syrups in a blender to make milkshakes. Milk is often served in coffee and tea. Frothy steamed milk is used to prepare espresso-based drinks such as cafe latte.

In language and culture

The importance of milk in human culture is attested to by the numerous expressions embedded in our languages, for example, "the milk of human kindness", the expression "there's no use crying over spilt milk" (which means do not "be unhappy about what cannot be undone"), "don't milk the ram" (this means "to do or attempt something futile") and "Why buy a cow when you can get milk for free?" (which means "why pay for something that you can get for free otherwise").[148]

In Greek mythology, the Milky Way was formed after the trickster god Hermes suckled the infant Heracles at the breast of Hera, the queen of the gods, while she was asleep.[149][150] When Hera awoke, she tore Heracles away from her breast and splattered her breast milk across the heavens.[149][150] In another version of the story, Athena, the patron goddess of heroes, tricked Hera into suckling Heracles voluntarily,[149][150] but he bit her nipple so hard that she flung him away, spraying milk everywhere.[149][150]

In many African and Asian countries, butter is traditionally made from fermented milk rather than cream. It can take several hours of churning to produce workable butter grains from fermented milk.[151]

Holy books have also mentioned milk. The Bible contains references to the "Land of Milk and Honey" as a metaphor for the bounty of the Promised Land. In the Qur'an, there is a request to wonder on milk as follows: "And surely in the livestock there is a lesson for you, We give you to drink of that which is in their bellies from the midst of digested food and blood, pure milk palatable for the drinkers" (16-The Honeybee, 66). The Ramadan fast is traditionally broken with a glass of milk and dates.

Abhisheka is conducted by Hindu and Jain priests, by pouring libations on the idol of a deity being worshipped, amidst the chanting of mantras. Usually offerings such as milk, yogurt, ghee, honey may be poured among other offerings depending on the type of abhishekam being performed.

A milksop is an "effeminate spiritless man," an expression which is attested to in the late 14th century.[11] Milk toast is a dish consisting of milk and toast. Its soft blandness served as inspiration for the name of the timid and ineffectual comic strip character Caspar Milquetoast, drawn by H. T. Webster from 1924 to 1952.[152] Thus, the term "milquetoast" entered the language as the label for a timid, shrinking, apologetic person. Milk toast also appeared in Disney's Follow Me Boys as an undesirable breakfast for the aging main character Lem Siddons.

To "milk" someone, in the vernacular of many English-speaking countries, is to take advantage of the person, by analogy to the way a farmer "milks" a cow and takes its milk. The word "milk" has had many slang meanings over time. In the 19th century, milk was used to describe a cheap and very poisonous alcoholic drink made from methylated spirits (methanol) mixed with water. The word was also used to mean defraud, to be idle, to intercept telegrams addressed to someone else, and a weakling or "milksop." In the mid-1930s, the word was used in Australia to refer to siphoning gas from a car.[153]

Non-culinary uses

Besides serving as a beverage or source of food, milk has been described as used by farmers and gardeners as an organic fungicide and fertilizer,[154][155][156] however, its effectiveness is debated. Diluted milk solutions have been demonstrated to provide an effective method of preventing powdery mildew on grape vines, while showing it is unlikely to harm the plant.[157][158]

Milk paint is a nontoxic water-based paint. It can be made from milk and lime, generally with pigments added for color.[159][160][161] In other recipes, borax is mixed with milk's casein protein in order to activate the casein and as a preservative.[162][163]

.jpg.webp)

Milk has been used for centuries as a hair and skin treatment. [164] Hairstylist Richard Marin states that some women rinse their hair with milk to add a shiny appearance to their hair.[164] Cosmetic chemist Ginger King states that milk can "help exfoliate and remove debris [from skin] and make hair softer. Hairstylist Danny Jelaca states that milk's keratin proteins may "add weight to the hair".[164] Some commercial hair products contain milk.[164]

A milk bath is a bath taken in milk rather than just water. Often additives such as oatmeal, honey, and scents such as rose, daisies and essential oils are mixed in. Milk baths use lactic acid, an alpha hydroxy acid, to dissolve the proteins which hold together dead skin cells.[165]

Interspecies milk consumption

The consumption of milk between species is not unique to humans. Seagulls, sheathbills, skuas, western gulls and feral cats have been reported to directly pilfer milk from the elephant seals' teats.[166][167][168][169]

Jewish/Kosher milk

Chalav Yisrael is the term of Jewish religious law regulating consumption of milk.[170][171][172]

See also

- A2 milk

- Babcock test (determines the butterfat content of milk)

- Blocked milk duct

- Bovine Meat and Milk Factors

- Fermented milk products

- Health mark

- Human breast milk

- Lactation

- List of dairy products

- List of national drinks

- Milk borne diseases

- Milk line

- Milk paint

- Milk substitute

- Oat milk

- Operation Flood

- World Milk Day

References

- Van Winckel, M; Velde, SV; De Bruyne, R; Van Biervliet, S (2011). "Clinical Practice". European Journal of Pediatrics. 170 (12): 1489–1494. doi:10.1007/s00431-011-1547-x. PMID 21912895. S2CID 26852044.

- Pehrsson, P.R.; Haytowitz, D.B.; Holden, J.M.; Perry, C.R.; Beckler, D.G. (2000). "USDA's National Food and Nutrient Analysis Program: Food Sampling" (PDF). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 13 (4): 379–89. doi:10.1006/jfca.1999.0867. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2003.

- "Food Outlook – Global Market Analysis" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. May 2012. pp. 8, 51–54. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- "World Dairy Cow Numbers". [FAO]. January 14, 2014. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- Anand Kumar (October 21, 2013). "India emerging as a leading milk product exporter". Dawn. Pakistan. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- "Government scraps incentive on milk powder exports to check prices". timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- "Milk quality in India". milkproduction.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- "Top Milk Exporting Countries". Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- "Cow's Milk and Milk Alternatives". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 25, 2022.

- Hemme, T.; Otte, J., eds. (2010). Status and Prospects for Smallholder Milk Production: A Global Perspective (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- "milk – Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. "General Standard for the Use of Dairy Terms 206-1999" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2017.

- Uruakpa, F.O.; Ismond, M.A.H.; Akobundu, E.N.T. (2002). "Colostrum and its benefits: A review". Nutrition Research. 22 (6): 755–67. doi:10.1016/S0271-5317(02)00373-1.

- Blood DC, Studdert VP, Gay CC (2007). Saunders Comprehensive Veterinary Dictionary. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevierv. ISBN 978-0-7020-2789-5.

- The World Health Organization's infant feeding recommendation Archived April 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine WHO, based on "Global strategy on infant and young child feeding" (2002). Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Dettwyler, Katherine A. (October 1997). "When to Wean". Natural History. Archived from the original on June 6, 2013. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- Basnet, S.; Schneider, M.; Gazit, A.; Mander, G.; Doctor, A. (April 2010). "Fresh Goat's Milk for Infants: Myths and Realities – A Review". Pediatrics. 125 (4): e973–77. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1906. PMID 20231186. S2CID 31557323.

- Curry, Andrew (July 31, 2013). "Archaeology: The milk revolution". Nature. 500 (7460): 20–22. Bibcode:2013Natur.500...20C. doi:10.1038/500020a. PMID 23903732.

- "Nutrition for Everyone: Basics: Saturated Fat – DNPAO". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on January 29, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- "Eat less saturated fat". National Health Service. April 27, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- Adam, Ana C.; Rubio-Texeira, Marta; Polaina, Julio (February 10, 2005). "Lactose: The Milk Sugar from a Biotechnological Perspective". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 44 (7–8): 553–557. doi:10.1080/10408690490931411. ISSN 1040-8398. PMID 15969327. S2CID 24005833.

- McGee, Harold (2004) [1984]. "Milk and Dairy Products". On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (2nd ed.). New York: Scribner. pp. 7–67. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archived from the original on December 26, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- "World's No 1 Milk Producer". Indiadairy.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- Goff, Douglas. "Introduction to Dairy Science and Technology: Milk History, Consumption, Production, and Composition: World-wide Milk Consumption and Production". Dairy Science and Technology. University of Guelph. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- Bellwood, Peter (2005). "The Beginnings of Agriculture in Southwest Asia". First Farmers: the origins of agricultural societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 44–68. ISBN 978-0-631-20566-1.

- Bellwood, Peter (2005). "Early Agriculture in the Americas". First Farmers: the origins of agricultural societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 146–79. ISBN 978-0-631-20566-1.

- Beja-Pereira, A.; Caramelli, D.; Lalueza-Fox, C.; Vernesi, C.; Ferrand, N.; Casoli, A.; Goyache, F.; Royo, L.J.; Conti, S.; Lari, M.; Martini, A.; Ouragh, L.; Magid, A.; Atash, A.; Zsolnai, A.; Boscato, P.; Triantaphylidis, C.; Ploumi, K.; Sineo, L.; Mallegni, F.; Taberlet, P.; Erhardt, G.; Sampietro, L.; Bertranpetit, J.; Barbujani, G.; Luikart, G.; Bertorelle, G. (2006). "The origin of European cattle: Evidence from modern and ancient DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (21): 8113–18. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103.8113B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509210103. PMC 1472438. PMID 16690747.

- Sherratt, Andrew (1981). "Plough and pastoralism: aspects of the secondary products revolution". In Hodder, I.; Isaac, G.; Hammond, N. (eds.). Pattern of the Past: Studies in honour of David Clarke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 261–305. ISBN 978-0-521-22763-6.

- Vigne, D.; Helmer, J.-D. (2007). "Was milk a 'secondary product' in the Old World Neolithisation process? Its role in the domestication of cattle, sheep and goats" (PDF). Anthropozoologica. 42 (2): 9–40. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2013.

- Evershed, R.P.; Payne, S.; Sherratt, A.G.; Copley, M.S.; Coolidge, J.; Urem-Kotsu, D.; Kotsakis, K.; Ozdoğan, M.; Ozdoğan, A.E.; Nieuwenhuyse, O.; Akkermans, P.M.M.G.; Bailey, D.; Andeescu, R.R.; Campbell, S.; Farid, S.; Hodder, I.; Yalman, N.; Ozbaşaran, M.; Biçakci, E.; Garfinkel, Y.; Levy, T.; Burton, M.M. (2008). "Earliest date for milk use in the Near East and southeastern Europe linked to cattle herding". Nature. 455 (7212): 528–31. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..528E. doi:10.1038/nature07180. PMID 18690215. S2CID 205214225.

- Price, T.D. (2000). "Europe's first farmers: an introduction". In T.D. Price (ed.). Europe's First Farmers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-521-66203-1.

- Meadow, R.H. (1996). "The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in northwestern South Asia". In D.R. Harris (ed.). The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. London: UCL Press. pp. 390–412. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3.

- Craig, Oliver E.; John Chapman; Carl Heron; Laura H. Willis; László Bartosiewicz; Gillian Taylor; Alasdair Whittle; Matthew Collins (2005). "Did the first farmers of central and eastern Europe produce dairy foods?". Antiquity. 79 (306): 882–94. arXiv:0706.4406. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00115017. hdl:10149/136330. S2CID 53378351.

- Copley, M.S.; Berstan, R.; Mukherjee, A.J.; Dudd, S.N.; Straker, V.; Payne, S.; Evershed, R.P. (2005). "Dairying in antiquity. III. Evidence from absorbed lipid residues dating to the British Neolithic". Journal of Archaeological Science. 32 (4): 523–56. Bibcode:2005JArSc..32..523C. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.08.006.

- Anthony, D.W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05887-0.

- Gifford-Gonzalez, D. (2004). "Pastoralism and its Consequences". In A.B. Stahl (ed.). African archaeology: a critical introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 187–224. ISBN 978-1-4051-0155-4.

- Peters, J. (1997). "The dromedary: Ancestry, history of domestication and medical treatment in early historic times". Tierarztliche Praxis. Ausgabe G, Grosstiere/Nutztiere. 25 (6): 559–65. PMID 9451759.

- Pećanac, M.; Janjić, Z.; Komarcević, A.; Pajić, M.; Dobanovacki, D.; Misković, SS. (2013). "Burns treatment in ancient times". Med Pregl. 66 (5–6): 263–67. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00603-5. PMID 23888738.

- Valenze, D.M. (2011). "Virtuous White Liquor in the Middle Ages". Milk: a local and global history. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-300-11724-0.

- Weaver, Lawrence Trevelyan (2021). White Blood: A History of Human Milk. Unicorn Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1913491260.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (November 8, 2020). "Americans have been enjoying nut milk and nut butter for at least 4 centuries". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- "Wabanaki Enjoying Nut Milk and Butter for Centuries". Atowi. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- Diemer-Eaton, Jessica (2014). "Food Nuts of the Eastern Woodlands Native Peoples". Woodland Indian Educational Programs. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- Bowling, G. A. (February 1, 1942). "The Introduction of Cattle into Colonial North America*". Journal of Dairy Science. 25 (2): 129–154. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(42)95275-5. ISSN 0022-0302.

- P.J. Atkins (1978). "The Growth of London's Railway Milk Trade, c. 1845–1914". Journal of Transport History. ss-4 (4): 208–26. doi:10.1177/002252667800400402. S2CID 158443104. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- "The History of Milk". DairyCo. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014.

- Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- "The History Of Milk", About.com. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- Vallery-Radot, René (2003). Life of Pasteur 1928. Kessinger. pp. 113–14. ISBN 978-0-7661-4352-4. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

- Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries, p. 357. John Wiley & Songs, Inc., New Jersey. ISBN 0-471-24410-4.

- Peter Atkins (January 2000). "The pasteurization of England: the science, culture and health implications of food processing, 1900–1950". Food, Science, Policy and Regulation in the 20th Century. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- Hwang, Andy; Huang, Lihan (January 31, 2009). Ready-to-Eat Foods: Microbial Concerns and Control Measures. CRC Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4200-6862-7. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- Gerosa and Skoet (2012). "Milk availability – Trends in production and demand and medium-term outlook" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- Why Bank Milk? Archived August 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Human Milk Banking Association of North America

- Grandell, Tommy (July 7, 2004). "Sweden's healthy moose cheese is a prized delicacy". GoUpstate. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- "About Bison: Frequently Asked Questions". National Bison Association. Archived from the original on February 11, 2006. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- Allen, Joel Asaph (June 1877). "Part II., Chapter 4. Domestication of the Buffalo". In Elliott Coues, Secretary of the Survey (ed.). History of the American Bison: bison americanus. extracted from the 9th Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey (1875). Washington, DC: Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey, Government Printing Office. pp. 585–86. OCLC 991639. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- O'Connor, George (March–April 1981). "The Basics of Beefalo Raising". Mother Earth News (68). Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2011.

- "Waarom drinken we de melk van varkens niet?". NRC. June 22, 2010. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- "Nieuw (en peperduur): kaas van varkensmelk – Plezier in de Keuken". Plezier in de Keuken. August 26, 2015. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

- "Dairy Market Review – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations" (PDF). UN Food & Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- "Milk, whole fresh cow producers". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Milk, whole fresh sheep producers". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Milk, whole fresh goat producers". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Milk, whole fresh buffalo producers". UN Food & Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Dairy production and products: Milk production". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- "Milk and milk product statistics – Statistics Explained". European Commission. Archived from the original on November 28, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Henriksen, J. (2009) "Milk for Health and Wealth". FAO Diversification Booklet Series 6, Rome

- Sinha, O.P. (2007) Agro-industries characterization and appraisal: Dairy in India Archived November 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, FAO, Rome

- "International Committee for Animal Recording". ICAR – icar.org. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- FAOSTAT, Yield data 2010 – Cow milk, whole, fresh Archived February 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, FAOSTAT, Food And Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; faostat.fao.org. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- Kerr R.B., Hasegawa T., Lasco R., Bhatt I., Deryng D., Farrell A., Gurney-Smith H., Ju H., Lluch-Cota S., Meza F., Nelson G., Neufeldt H., Thornton P., 2022: Chapter 5: Food, Fibre and Other Ecosystem Products. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke,V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 1457–1579 |doi=10.1017/9781009325844.012

- Ahmed, Haseeb; Tamminen, Lena-Mari; Emanuelson, Ulf (November 22, 2022). "Temperature, productivity, and heat tolerance: Evidence from Swedish dairy production". Climatic Change. 175 (1–2): 1269–1285. Bibcode:2022ClCh..175...10A. doi:10.1007/s10584-022-03461-5. S2CID 253764271.

- Pramod, S.; Sahib, Lasna; Becha B, Bibin; Venkatachalapathy, R. Thirupathy (January 3, 2021). "Analysis of the effects of thermal stress on milk production in a humid tropical climate using linear and non-linear models". Tropical Animal Health and Production. 53 (1): 1269–1285. doi:10.1007/s11250-020-02525-x. PMID 33392887. S2CID 255113614.

- Blanco-Penedo, Isabel; Velarde, Antonio; Kipling, Richard P.; Ruete, Alejandro (August 25, 2020). "Modeling heat stress under organic dairy farming conditions in warm temperate climates within the Mediterranean basin". Climatic Change. 162 (3): 1269–1285. Bibcode:2020ClCh..162.1269B. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02818-y. S2CID 221283658.

- Ranjitkar, Sailesh; Bu, Dengpan; Van Wijk, Mark; Ma, Ying; Ma, Lu; Zhao, Lianshen; Shi, Jianmin; Liu, Chousheng; Xu, Jianchu (April 2, 2020). "Will heat stress take its toll on milk production in China?". Climatic Change. 161 (4): 637–652. Bibcode:2020ClCh..161..637R. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02688-4. S2CID 214783104.