History of Antarctica

The history of Antarctica emerges from early Western theories of a vast continent, known as Terra Australis, believed to exist in the far south of the globe. The term Antarctic, referring to the opposite of the Arctic Circle, was coined by Marinus of Tyre in the 2nd century AD.

The rounding of the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn in the 15th and 16th centuries proved that Terra Australis Incognita ("Unknown Southern Land"), if it existed, was a continent in its own right. In 1773, James Cook and his crew crossed the Antarctic Circle for the first time. Although he discovered new islands, he did not sight the continent itself. It is believed that he came as close as 240 km (150 mi) from the mainland.

On 27 January 1820, a Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev discovered an ice shelf at Princess Martha Coast that later became known as the Fimbul Ice Shelf. Bellingshausen and Lazarev became the first explorers to see and officially discover the land of the continent of Antarctica. Three days later, on 30 January 1820, a British expedition captained by Irishman Edward Bransfield sighted Trinity Peninsula, and ten months later an American sealer, Nathaniel Palmer, sighted Antarctica on 17 November 1820. The first landing was most likely just over a year later when American Captain John Davis, a sealer, set foot on the ice.

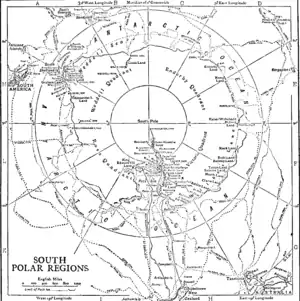

Several expeditions attempted to reach the South Pole in the early 20th century, during the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration". Many resulted in injury and death. Norwegian Roald Amundsen finally reached the Pole on 14 December 1911, following a dramatic race with the Briton Robert Falcon Scott.

Early exploration

The search for Terra Australis Incognita

Aristotle speculated, "Now since there must be a region bearing the same relation to the southern pole as the place we live in bears to our pole...".[1]

Some authors have suggested that a figure in Māori oral tradition, Hui Te Rangiora (also known as 'Ui Te Rangiora) and his crew explored Antarctic waters in the early seventh century on the vessel Te Ivi o Atea.[2] Accounts name the area "Te tai-uka-a-pia", which describes a 'frozen ocean' and 'arrowroot', which resembles fresh snow when scraped.[3][2][4] However, this interpretation of the original account is disputed by Te Rangi Hīroa (Sir Peter Henry Buck) who lists evidence for his belief that 'later historians embellished the tales by adding details learned from European whalers and teachers'.[5] This interpretation of oral history and the probability of such a voyage have likewise been dismissed more recently by Ngāi Tahu scholars, who agree that 'it is very unlikely that Māori or other Polynesian voyaging reached the Antarctic'.[6][7]

It was not until Prince Henry the Navigator began in 1418 to encourage the penetration of the torrid zone in the effort to reach India by circumnavigating Africa that European exploration of the southern hemisphere began.[8] In 1473, Portuguese navigator Lopes Gonçalves proved that the equator could be crossed, and cartographers and sailors began to assume the existence of another, temperate continent to the south of the known world.

The doubling of the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 by Bartolomeu Dias first brought explorers within touch of the Antarctic cold, and proved that there was an ocean separating Africa from any Antarctic land that might exist.[8]

Ferdinand Magellan, who passed through the Straits of Magellan in 1520, assumed that the islands of Tierra del Fuego to the south were an extension of this unknown southern land, and it appeared as such on a map by Ortelius: Terra australis recenter inventa sed nondum plene cognita ("Southern land recently discovered but not yet fully known").[9]

%252C_Spain.svg.png.webp)

In 1539, the King of Spain, Charles V, created the Governorate of Terra Australis[10] granted to Pedro Sancho de la Hoz,[11][12] who in 1540 transferred the title to the conqueror Pedro de Valdivia[13] and later was incorporated to Chile.

European geographers connected the coast of Tierra del Fuego with the coast of New Guinea on their globes, and allowing their imaginations to run riot in the vast unknown spaces of the south Atlantic, south Indian and Pacific oceans they sketched the outlines of the Terra Australis Incognita ("Unknown Southern Land"), a vast continent stretching in parts into the tropics. The search for this great south land or Third World was a leading motive of explorers in the 16th and the early part of the 17th centuries.[8] In 1599, according to the account of Jacob le Maire, the Dutch Dirck Gerritsz Pomp observed mountainous land at latitude (64°). If so, these were the South Shetland Islands, and possibly the first European sighting of Antarctica (or offshore-lying islands belonging to it). Other accounts, however, do not note this observation, casting doubt on their accuracy. It has been argued that the Spaniard Gabriel de Castilla claimed to have sighted "snow-covered mountains" beyond the 64° S in 1603, but this claim is not generally recognized.

Quirós, in 1606, took possession for the king of Spain all of the lands he had discovered in Australia del Espiritu Santo (the New Hebrides) and those he would discover "even to the Pole".[8]

Francis Drake, like Spanish explorers before him, had speculated that there might be an open channel south of Tierra del Fuego. Indeed, when Schouten and Le Maire discovered the southern extremity of Tierra del Fuego and named it Cape Horn in 1615, they proved that the Tierra del Fuego archipelago was of small extent and not connected to the southern land.[8]

Finally, in 1642, Tasman showed that even New Holland (Australia) was separated by sea from any continuous southern continent. Voyagers round the Horn frequently met with contrary winds and were driven southward into snowy skies and ice-encumbered seas; but, so far as can be ascertained, none of them before 1770 reached the Antarctic Circle, or knew it, if they did.[8]

The Dutch expedition to Valdivia of 1643 intended to round Cape Horn sailing through Le Maire Strait but strong winds made it instead drift south and east.[14] Northerly winds pushed the expedition as far south as 61°59 S where icebergs were abundant before a southerly wind that begun on April 7 allowed the fleet to advance west.[14] The small fleet led by Hendrik Brouwer managed to enter the Pacific Ocean sailing south of Isla de los Estados disproving earlier beliefs that it was part of Terra Australis.[14][15][16]

South of the Antarctic Convergence

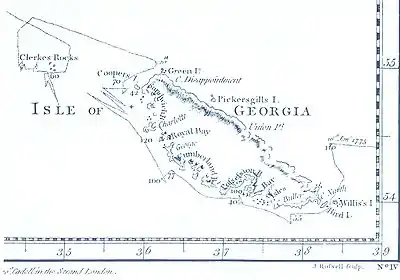

The visit to South Georgia by the English merchant Anthony de la Roché in 1675 was the first ever discovery of land south of the Antarctic Convergence.[17][18] Soon after the voyage cartographers started to depict 'Roché Island', honouring the discoverer.

James Cook was aware of La Roché's discovery when surveying and mapping the island in 1775.[19]

Edmond Halley's voyage in HMS Paramour for magnetic investigations in the South Atlantic met the pack ice in 52° S in January 1700, but that latitude (he reached 140 mi or 230 km off the north coast of South Georgia) was his farthest south. A determined effort on the part of the French naval officer Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier to discover the "South Land" – described by a half legendary "sieur de Gonneyville" – resulted in the discovery of Bouvet Island in 54°10′ S, and in the navigation of 48° of longitude of ice-cumbered sea nearly in 55° S in 1739.[8]

In 1771, Yves Joseph Kerguelen sailed from France with instructions to proceed south from Mauritius in search of "a very large continent." He lighted upon a land in 50° S which he called South France, and believed to be the central mass of the southern continent. He was sent out again to complete the exploration of the new land, and found it to be only an inhospitable island which he renamed the Isle of Desolation, but which was ultimately named after him.[8]

The Antarctic Circle

The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of Alexander Dalrymple, the brilliant and erratic hydrographer who was nominated by the Royal Society to command the Transit of Venus expedition to Tahiti in 1769. The command of the expedition was given by the admiralty to Captain James Cook. Sailing in 1772 with the Resolution, a vessel of 462 tons under his own command and the Adventure of 336 tons under Captain Tobias Furneaux, Cook first searched in vain for Bouvet Island, then sailed for 20 degrees of longitude to the westward in latitude 58° S, and then 30° eastward for the most part south of 60° S, a higher southern latitude than had ever been voluntarily entered before by any vessel. On 17 January 1773 the Antarctic Circle was crossed for the first time in history and the two ships reached 67° 15' S by 39° 35' E, where their course was stopped by ice.[8]

Cook then turned northward to look for French Southern and Antarctic Lands, of the discovery of which he had received news at Cape Town, but from the rough determination of his longitude by Kerguelen, Cook reached the assigned latitude 10° too far east and did not see it. He turned south again and was stopped by ice in 61° 52′ S by 95° E and continued eastward nearly on the parallel of 60° S to 147° E. On 16 March, the approaching winter drove him northward for rest to New Zealand and the tropical islands of the Pacific. In November 1773, Cook left New Zealand, having parted company with the Adventure, and reached 60° S by 177° W, whence he sailed eastward keeping as far south as the floating ice allowed. The Antarctic Circle was crossed on 20 December and Cook remained south of it for three days, being compelled after reaching 67° 31′ S to stand north again in 135° W.[8]

A long detour to 47° 50′ S served to show that there was no land connection between New Zealand and Tierra del Fuego. Turning south again, Cook crossed the Antarctic Circle for the third time at 109° 30′ W before his progress was once again blocked by ice four days later at 71° 10′ S by 106° 54′ W. This point, reached on 30 January 1774, was the farthest south attained in the 18th century. With a great detour to the east, almost to the coast of South America, the expedition regained Tahiti for refreshment. In November 1774, Cook started from New Zealand and crossed the South Pacific without sighting land between 53° and 57° S to Tierra del Fuego; then, passing Cape Horn on 29 December, he rediscovered Roché Island renaming it Isle of Georgia, and discovered the South Sandwich Islands (named Sandwich Land by him), the only ice-clad land he had seen, before crossing the South Atlantic to the Cape of Good Hope between 55° and 60°. He thereby laid open the way for future Antarctic exploration by exploding the myth of a habitable southern continent. Cook's most southerly discovery of land lay on the temperate side of the 60th parallel, and he convinced himself that if land lay farther south it was practically inaccessible and of no economic value.[8]

First sighting

The first land south of the parallel 60° south latitude was documented by Englishman William Smith, who sighted Livingston Island in the South Shetlands archipelago on 19 February 1819. He found some remnants and signs of the wreckage of the Spanish ship San Telmo, but it is unknown if any surviving crew had landed there.[20][21][22][23][24][25] A few months later, Smith returned to explore the archipelago, landed on King George Island, and claimed the new territories for Britain.

The first confirmed sighting of mainland Antarctica is attributed to the Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev, on the ships Vostok and Mirny. On 27 or 28 January 1820,[26] at a point within 32 km (20 mi) of Princess Martha Coast, they recorded the presence of the Fimbul Ice Shelf at 69°21′28″S 2°14′50″W.[27] Meanwhile, on 30 January 1820, Irishman Edward Bransfield sighted Trinity Peninsula, the northernmost point of the Antarctic mainland. Von Bellingshausen's expedition also discovered Peter I Island and Alexander I Island, the first islands to be discovered south of the Antarctic Circle.

Early exploration

The first landing on the Antarctic mainland is thought to have been made by the American Captain John Davis, a sealer, who claimed to have set foot there on 7 February 1821,[28] though this is not accepted by all historians.[29]

In November 1820, Nathaniel Palmer, an American sealer looking for seal breeding grounds, using maps made by the Loper whaling family, sighted what is now known as the Antarctic Peninsula, located between 55 and 80 degrees west. In 1823, James Weddell, a British sealer, sailed into what is now known as the Weddell Sea. Until the twentieth century, most expeditions were for commercial purpose, to look for the prospects of seal and whale hunting. A piece of wood, from the South Shetland Islands, was the first fossil ever recorded from Antarctica, obtained during a private United States expedition during 1829–31, commanded by Captain Benjamin Pendleton.[30][31][32]

Charles Wilkes, as commander of a United States Navy expedition in 1840,[33] discovered what is now known as Wilkes Land, a section of the continent around 120 degrees East.

After the North Magnetic Pole was located in 1831, explorers and scientists began looking for the South Magnetic Pole. One of the explorers, James Clark Ross, a British naval officer, identified its approximate location, but was unable to reach it on his 4 year-expedition from 1839 to 1843. Commanding the British ships Erebus and Terror, he braved the pack ice and approached what is now known as the Ross Ice Shelf, a massive floating ice shelf over 100 feet (30 m) high. His expedition sailed eastward along the southern Antarctic coast discovering mountains which were since named after his ships: Mount Erebus, the most active volcano on Antarctica, and Mount Terror.[33]

The first documented landing on the mainland of East Antarctica was at Victoria Land by the American sealer Mercator Cooper on 26 January 1853.[34]

These explorers, despite their impressive contributions to South Polar exploration, were unable to penetrate the interior of the continent and, rather, formed a broken line of discovered lands along the coastline of Antarctica. Following the expedition south by the ships Erebus and Terror, James Clark Ross (January, 1841) suggested that there were no scientific discoveries, or 'problems', worth exploration in the far South.[35] What followed is what historian H.R. Mill called 'the age of averted interest'[35] and in the following twenty years after Ross' return, there was a general lull internationally in Antarctic exploration.[35]

Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration began at the end of the 19th century and closed with Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1917.[36]

During this period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort that resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration and in which 17 major Antarctic expeditions were launched from ten countries.[37]

Origins

An important precursor to the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration was the Dundee Antarctic Expedition of 1892-93 in which four Dundee whaling ships travelled south to the Antarctic in search of whales instead of their usual Arctic route. The expedition was accompanied by several naturalists (including Williams Speirs Bruce) and an artist, William Gordon Burn Murdoch. The publications (both scientific and popular) and exhibitions that resulted did much to reignite public interest in the Antarctic. The performance of the whaling ships was also crucial in the decision to build the RRS Discovery in Dundee.[38]

Following on from that expedition, the specific impetus for the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was a lecture given by Dr John Murray entitled "The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration", given to the Royal Geographical Society in London, 27 November 1893.[39] Murray advocated that research into the Antarctic should be organised to "resolve the outstanding geographical questions still posed in the south".[40] Furthermore, the Royal Geographical Society instated an Antarctic Committee shortly prior to this, in 1887, which successfully encouraged many whalers to explore the Southern regions of the world and laid the groundwork for the lecture given by Murray.[41]

The Norwegian ship Antarctic was put ashore at Cape Adare, on 24 January 1895.[42]

In August 1895 the Sixth International Geographical Congress in London passed a general resolution calling on scientific societies throughout the world to promote the cause of Antarctic exploration "in whatever ways seem to them most effective".[43] Such work would "bring additions to almost every branch of science".[43] The Congress had been addressed by the Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink, who had just returned from a whaling expedition during which he had become one of the first to set foot on the Antarctic mainland.[8] During his address, Borchgrevink outlined plans for a full-scale pioneering Antarctic expedition, to be based at Cape Adare.[44][45]

The Heroic Age was inaugurated by an expedition launched by the Belgian Geographical Society in 1897; Borchgrevink followed a year later with a privately sponsored British expedition.[46] (Some histories consider the Discovery expedition, which departed in 1901, as the first proper expedition of the Heroic Age.[47])

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition was led by Belgian Adrian de Gerlache. In 1898, they became the first men to spend winter on Antarctica, when their ship Belgica became trapped in the ice. They became stuck on 28 February 1898, and only managed to get out of the ice on 14 March 1899.

During their forced stay, several men lost their sanity, not only because of the Antarctic winter night and the endured hardship, but also because of the language problems between the different nationalities. This was the first expedition to overwinter within the Antarctic Circle,[48][49] and they visited the South Shetland Islands.[50]

Early British expeditions

The Southern Cross Expedition began in 1898 and lasted for two years. This was the first expedition to overwinter on the Antarctic mainland (Cape Adare) and was the first to make use of dogs and sledges. It made the first ascent of The Great Ice Barrier, (The Great Ice Barrier later became formally known as the Ross Ice Shelf). The expedition set a Farthest South record at 78°30'S. It also calculated the location of the South Magnetic Pole.[51][52]

The Discovery Expedition was then launched, from 1901 to 1904 and was led by Robert Falcon Scott. It made the first ascent of the Western Mountains in Victoria Land, and discovered the polar plateau. Its southern journey set a new Farthest South record, 82°17'S. Many other geographical features were discovered, mapped and named. This was the first of several expeditions based in McMurdo Sound.[53][54][55]

A year later, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition was launched, headed by William Speirs Bruce. 'Ormond House' was established as a meteorological observatory on Laurie Island in the South Orkneys and was the first permanent base in Antarctica. The Weddell Sea was penetrated to 74°01'S, and the coastline of Coats Land was discovered, defining the sea's eastern limits.[56][57][58]

Ernest Shackleton, who had been a member of Scott's expedition, organized and led the Nimrod Expedition from 1907 to 1909. The expedition's primary objective was of reaching the South Pole. Based in McMurdo Sound, the expedition pioneered the Beardmore Glacier route to the South Pole, and the (limited) use of motorised transport. Its southern march reached 88°23'S, a new Farthest South record 97 geographical miles from the Pole before having to turn back. During the expedition, Shackleton was the first to reach the polar plateau. Parties led by T. W. Edgeworth David also became the first to climb Mount Erebus and to reach the South Magnetic Pole.[59][60][61]

Expeditions from other countries

The First German Antarctic Expedition was sent to investigate eastern Antarctica in 1901. It discovered the coast of Kaiser Wilhelm II Land, and Mount Gauss. The expedition's ship became trapped in ice, however, which prevented more extensive exploration.[62][63][64]

The Swedish Antarctic Expedition, operating at the same time worked in the east coastal area of Graham Land, and was marooned on Snow Hill Island and Paulet Island in the Weddell Sea, after the sinking of its expedition ship. It was rescued by the Argentinian naval vessel Uruguay.[65][66][67]

The French organized their first expedition in 1903 under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Charcot. Originally intended as a relief expedition for the stranded Nordenskiöld party, the main work of this expedition was the mapping and charting of islands and the western coasts of Graham Land, on the Antarctic peninsula. A section of the coast was explored, and named Loubet Land after the President of France.[68][69][70]

A follow-up trip was organized from 1908 to 1910 which continued the earlier work of the French expedition with a general exploration of the Bellingshausen Sea, and the discovery of islands and other features, including Marguerite Bay, Charcot Island, Renaud Island, Mikkelsen Bay, Rothschild Island.[71]

Race to the South Pole

The prize of the Heroic Age was to find and reach the South Pole. Two expeditions set off in 1910 to attain this goal; a party led by Norwegian Polar explorer Roald Amundsen from the ship Fram and Robert Falcon Scott's British group from the Terra Nova.

Amundsen succeeded in reaching the Pole on 14 December 1911 using a route from the Bay of Whales to the polar plateau via the Axel Heiberg Glacier.[72][73][74]

Scott and his four companions reached the South Pole via the Beardmore route on 17 January 1912, 33 days after Amundsen. All five died on the return journey from the Pole, through a combination of starvation and cold.[75] The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station was later named after these two men.

Further expeditions

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition took place between 1911–1914 and was led by Sir Douglas Mawson. It concentrated on the stretch of Antarctic coastline between Cape Adare and Mount Gauss, carrying out mapping and survey work on coastal and inland territories.

Discoveries included Commonwealth Bay, Ninnis Glacier, Mertz Glacier, and Queen Mary Land. Major accomplishments were made in geology, glaciology and terrestrial biology.[76]

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 was led by Ernest Shackleton and set out to cross the continent via the South pole. However, their ship, the Endurance, was trapped and crushed by pack ice in the Weddell Sea before they were able to land. The expedition members survived after a journey on sledges over pack ice, a prolonged drift on an ice-floe, and a voyage in three small boats to Elephant Island. Then Shackleton and five others crossed the Southern Ocean in an open boat called James Caird and made the first crossing of South Georgia to raise the alarm at the whaling station Grytviken.[77]

A related component of the Trans-Antarctic Expedition was the Ross Sea party, led by Aeneas Mackintosh. Its objective was to lay depots across the Great Ice Barrier, in order to supply Shackleton's party crossing from the Weddell Sea. All the required depots were laid, but in the process three men, including the leader Mackintosh, died.[78]

Shackleton's last expedition and the one that brought the 'Heroic Age' to a close, was the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition from 1921 to 1922 on board the ship Quest. Its vaguely defined objectives included coastal mapping, a possible continental circumnavigation, the investigation of sub-Antarctic islands, and oceanographic work. After Shackleton's death on 5 January 1922, Quest completed a shortened programme before returning home.[79]

Further exploration

By air

After Shackleton's last expedition, there was a hiatus in Antarctic exploration for about seven years. From 1929, aircraft and mechanized transportation were increasingly used, earning this period the sobriquet of the 'Mechanical Age'. Hubert Wilkins first visited Antarctica in 1921–1922 as an ornithologist attached to the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition. From 1927, Wilkins and pilot Carl Ben Eielson began exploring the Arctic by aircraft.[80]

On 15 April 1928, only a year after Charles Lindbergh's flight across the Atlantic, Wilkins and Eielson made a trans-Arctic crossing from Point Barrow, Alaska, to Spitsbergen, arriving about 20 hours later on 16 April, touching along the way at Grant Land on Ellesmere Island.[81] For this feat and his prior work, Wilkins was knighted.

With financial backing from William Randolph Hearst, Wilkins returned to the South Pole and flew over Antarctica in the San Francisco. He named the island of Hearst Land after his sponsor.

US Navy Rear Admiral Richard Evelyn Byrd led five expeditions to Antarctica during the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. He overflew the South Pole with pilot Bernt Balchen on 28 and 29 November 1929, to match his overflight of the North Pole in 1926. Byrd's explorations had science as a major objective and extensively used the aircraft to explore the continent.

Captain Finn Ronne, Byrd's executive officer, returned to Antarctica with his own expedition in 1947–1948, with Navy support, three planes, and dogs. Ronne disproved the notion that the continent was divided in two and established that East and West Antarctica was one single continent, i.e. that the Weddell Sea and the Ross Sea are not connected.[82] The expedition explored and mapped large parts of Palmer Land and the Weddell Sea coastline, and identified the Ronne Ice Shelf, named by Ronne after his wife Edith Ronne.[83] Ronne covered 5,800 kilometres (3,600 mi) by ski and dog sled—more than any other explorer in history.[84]

Overland crossing

The 1955–58 Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition successfully completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica, via the South Pole. Although supported by the British and other Commonwealth governments, most of the funding came from corporate and individual donations.

It was headed by British explorer Dr Vivian Fuchs, with New Zealander Sir Edmund Hillary leading the New Zealand Ross Sea Support team. After spending the winter of 1957 at Shackleton Base, Fuchs finally set out on the transcontinental journey in November 1957, with a twelve-man team travelling in six vehicles; three Sno-Cats, two Weasels and one specially adapted Muskeg tractor. En route, the team were also tasked with carrying out scientific research including seismic soundings and gravimetric readings.

In parallel Hillary's team had set up Scott Base – which was to be Fuchs' final destination – on the opposite side of the continent at McMurdo Sound on the Ross Sea. Using three converted Massey Ferguson TE20 tractors[85] and one Weasel (abandoned part-way), Hillary and his three men (Ron Balham, Peter Mulgrew and Murray Ellis), were responsible for route-finding and laying a line of supply depots up the Skelton Glacier and across the Polar Plateau on towards the South Pole, for the use of Fuchs on the final leg of his journey. Other members of Hillary's team carried out geological surveys around the Ross Sea and Victoria Land areas.

Hillary's party reached the South Pole on 3 January 1958, and was just the third (preceded by Amundsen in 1911 and Scott in 1912) to reach the Pole overland. Fuchs' team reached the Pole from the opposite direction on 19 January 1958, where they met up with Hillary. Fuchs then continued overland, following the route that Hillary had laid and on 2 March succeeded in reaching Scott Base, completing the first overland crossing of the continent by land via the South Pole.[33]

Political history

Spanish claims

.jpg.webp)

According to Argentina and Chile, the Spanish Empire had claims on Antarctica. The capitulación (governorship) granted to the conquistador Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz in 1539 by the King of Spain, Charles V, explicitly included all lands south of the Straits of Magellan, (Terra Australis, and Tierra del Fuego and by extension potentially the entire continent of Antarctica) and to the East and West the borders were the ones specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas and Zaragoza, respectively, thus creating the Governorate of Terra Australis.[10][11][12]

De la Hoz transferred the title to the conqueror Pedro de Valdivia in 1540.[86] In 1555 the claim was incorporated to Chile.[87]

This grant established, according to Argentina and Chile, that an animus occupandi existed on the part of Spain in Antarctica. Spain's sovereignty claim over parts of Antarctica was, according to Chile and Argentina, internationally recognized with the Inter caetera bull of 1493 and the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494. Argentina and Chile treat these treaties as legal international treaties mediated by the Catholic Church that was at that time a recognized arbiter in such matters.[88] Each country currently has claimed a sector of the Antarctic continent that is more or less directly south of its national antarctic-facing lands.

Modern Spain has not claimed any Antarctic territory. It operates two summer research stations (Gabriel de Castilla Base and Juan Carlos I Base) in the South Shetland Islands.

British claims

The United Kingdom reasserted sovereignty over the Falkland Islands in the far South Atlantic in 1833 and maintained a continuous presence there. In 1908, the British government extended its territorial claim by declaring sovereignty over "South Georgia, the South Orkneys, the South Shetlands, and the Sandwich Islands, and Graham's Land, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean and on the Antarctic continent to the south of the 50th parallel of south latitude, and lying between the 20th and the 80th degrees of west longitude".[89] All these territories were administered as Falkland Islands Dependencies from Stanley by the Governor of the Falkland Islands. The motivation for this declaration lay in the need for regulating and taxing the whaling industry effectively. Commercial operators would hunt whales in areas outside of the official boundaries of the Falkland Islands and its dependencies and there was a need to close this loophole.

In 1917, the wording of the claim was modified, so as to, among other things, unambiguously include all the territory in the sector stretching to the South Pole (thus encompassing all of the present-day British Antarctic Territory). The new claim covered "all islands and territories whatsoever between the 20th degree of west longitude and the 50th degree of west longitude which are situated south of the 50th parallel of south latitude; and all islands and territories whatsoever between the 50th degree of west longitude and the 80th degree of west longitude which are situated south of the 58th parallel of south latitude".[89]

Under the ambition of Leopold Amery, the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, Britain attempted to incorporate the entire continent into the Empire. In a memorandum to the governor-generals for Australia and New Zealand, he wrote that 'with the exception of Chile and Argentina and some barren islands belonging to France... it is desirable that the whole of the Antarctic should ultimately be included in the British Empire.'

The first step was taken on 30 July 1923, when the British government passed an Order in Council under the British Settlements Act 1887, defining the new borders for the Ross Dependency - "that part of His Majesty's Dominions in the Antarctic Seas, which comprises all the islands and territories between the 160th degree of East Longitude and the 150th degree of West Longitude which are situated south of the 60th degree of South Latitude shall be named the Ross Dependency."

The Order in Council then went on to appoint the Governor-General and Commander-in Chief of New Zealand as the Governor of the territory.[90]

In 1930, the United Kingdom claimed Enderby Land. In 1933, a British imperial order transferred territory south of 60° S and between meridians 160° E and 45° E to Australia as the Australian Antarctic Territory.[91][92]

Following the passing of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, the government of the United Kingdom relinquished all control over the government of New Zealand and Australia. This however had no bearing on the obligations of the Governor-General of both countries in their capacity as Governor of the Antarctic territories.

Other European claims

Meanwhile, alarmed by these unilateral declarations, the French government laid claim to a strip of the continent in 1924. The basis for their claim to Adélie Land lay on the discovery of the coastline in 1840 by the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville, who named it after his wife, Adèle.[93] The British eventually decided to recognize this claim and the border between Adélie Land and Australian Antarctic Territory was fixed definitively in 1938.[94]

These developments also concerned Norwegian whaling interests, who wished to avoid the British taxation of whaling stations in the Antarctic and were concerned that they would be commercially excluded from the continent. The whale-ship owner Lars Christensen financed several expeditions to the Antarctic with the view to claim land for Norway and establish stations on Norwegian territory to gain better privileges.[95] The first expedition, led by Nils Larsen and Ola Olstad, landed on Peter I Island in 1929 and claimed the island for Norway. On 6 March 1931, a Norwegian royal proclamation declared the island under Norwegian sovereignty[95] and on 23 March 1933 the island was declared a dependency.[96]

The 1929 expedition led by Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen and Finn Lützow-Holm named the continental land mass near the island as Queen Maud Land, named after the Norwegian queen Maud of Wales.[97] The territory was explored further during the Norvegia expedition of 1930–31.[98] Negotiations with the British government in 1938 resulted in the western border of Queen Maud Land being set at 20°W.[98]

Norway's claim was disputed by Nazi Germany,[99] which in 1938 dispatched the German Antarctic Expedition, led by Alfred Ritscher, to fly over as much of it as possible.[98] The ship Schwabenland reached the pack ice off Antarctica on 19 January 1939.[100] During the expedition, an area of about 350,000 square kilometres (140,000 sq mi) was photographed from the air by Ritscher,[101] who dropped darts inscribed with swastikas every 26 kilometres (16 mi). Germany eventually attempted to claim the territory surveyed by Ritscher under the name New Swabia, but lost any claim to the land following its defeat in the Second World War.[99]

On 14 January 1939, five days prior to the German arrival, Queen Maud Land was annexed by Norway,[97] after a royal decree announced that the land bordering the Falkland Islands Dependencies in the west and the Australian Antarctic Dependency in the east was to be brought under Norwegian sovereignty.[98] The primary basis for the annexation was to secure the Norwegian whaling industry's access to the region.[97][102] In 1948, Norway and the United Kingdom agreed to limit Queen Maud Land to from 20°W to 45°E, and that the Bruce Coast and Coats Land were to be incorporated into Norwegian territory.[98]

South American involvement

This encroachment of foreign powers was a matter of immense disquiet to the nearby South American countries, Argentina and Chile. Taking advantage of a European continent plunged into turmoil with the onset of the Second World War, Chile's president, Pedro Aguirre Cerda declared the establishment of a Chilean Antarctic Territory in areas already claimed by Britain.

Argentina had an even longer history of involvement in the Continent. Already in 1904 the Argentine government began a permanent occupation in the area with the purchase of a meteorological station on Laurie Island established in 1903 by Dr William S. Bruce's Scottish National Antarctic Expedition. Bruce offered to transfer the station and instruments for the sum of 5.000 pesos, on the condition that the government committed itself to the continuation of the scientific mission.[103] British officer William Haggard also sent a note to the Argentine Foreign Minister, Jose Terry, ratifying the terms of Bruce proposition.[103]

In 1906, Argentina communicated to the international community the establishment of a permanent base on South Orkney Islands. However, Haggard responded by reminding Argentina that the South Orkneys were British. The British position was that Argentine personnel was granted permission only for the period of one year. The Argentine government entered into negotiations with the British in 1913 over the possible transfer of the island. Although these talks were unsuccessful, Argentina attempted to unilaterally establish their sovereignty with the erection of markers, national flags and other symbols. [104] Finally, with British attention elsewhere, Argentina declared the establishment of Argentine Antarctica in 1943, claiming territory that overlapped with British ( 20°W to 80°W) and the earlier Chilean (53°W to 90°W) claims.

In response to this and earlier German explorations, the British Admiralty and Colonial Office launched Operation Tabarin in 1943 to reassert British territorial claims against Argentine and Chilean incursion and establish a permanent British presence in the Antarctic.[105] The move was also motivated by concerns within the Foreign Office about the direction of United States post-war activity in the region.

A suitable cover story was the need to deny use of the area to the enemy. The Kriegsmarine was known to use remote islands as rendezvous points and as shelters for commerce raiders, U-boats and supply ships. Also, in 1941, there existed a fear that Japan might attempt to seize the Falkland Islands, either as a base or to hand them over to Argentina, thus gaining political advantage for the Axis and denying their use to Britain.

In 1943, British personnel from HMS Carnarvon Castle[106] removed Argentine flags from Deception Island. The expedition was led by Lieutenant James Marr and left the Falkland Islands in two ships, HMS William Scoresby (a minesweeping trawler) and Fitzroy, on Saturday 29 January 1944.

Bases were established during February near the abandoned Norwegian whaling station on Deception Island, where the Union Flag was hoisted in place of Argentine flags, and at Port Lockroy (on February 11) on the coast of Graham Land. A further base was founded at Hope Bay on 13 February 1945, after a failed attempt to unload stores on 7 February 1944. Symbols of British sovereignty, including post offices, signposts and plaques were also constructed and postage stamps were issued.

Operation Tabarin provoked Chile to organize its First Chilean Antarctic Expedition in 1947–48, where the Chilean president Gabriel González Videla personally inaugurated one of its bases.[107]

Following the end of the war in 1945, the British bases were handed over to civilian members of the newly created Falkland Islands Dependencies Survey (subsequently the British Antarctic Survey) the first such national scientific body to be established in Antarctica.

Post-war developments

Friction between Britain and the Latin American states continued into the post war period. Royal Navy warships were despatched in 1948 to prevent naval incursions and in 1952, an Argentine shore party at Hope Bay (the British Base "D", established there in 1945, came up against the Argentine Esperanza Base, est. 1952) fired a machine gun over the heads of a British Antarctic Survey team unloading supplies from the John Biscoe. The Argentines later extended a diplomatic apology, saying that there had been a misunderstanding and that the Argentine military commander on the ground had exceeded his authority.

The United States became politically interested in the Antarctic continent before and during WWII. The United States Antarctic Service Expedition, from 1939 to 1941, was sponsored by the government with additional support came from donations and gifts by private citizens, corporations and institutions. The objectives of the Expedition, outlined by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was to establish two bases: East Base, in the vicinity of Charcot Island, and West Base, in the vicinity of King Edward VII Land. After operating successfully for two years, but with international tensions on the rise, it was considered wise to evacuate the two bases.[108]

However, immediately after the war, American interest was rekindled with an explicitly geopolitical motive. Operation Highjump, from 1946 to 1947 was organized by Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd Jr. and included 4,700 men, 13 ships, and multiple aircraft. The primary mission of Operation Highjump was to establish the Antarctic research base Little America IV,[109] for the purpose of training personnel and testing equipment in frigid conditions and amplifying existing stores of knowledge of hydrographic, geographic, geological, meteorological and electromagnetic propagation conditions in the area. The mission was also aimed at consolidating and extending United States sovereignty over the largest practicable area of the Antarctic continent, although this was publicly denied as a goal even before the expedition ended.

Towards an international treaty

Meanwhile, in an attempt at ending the impasse, Britain submitted an application to the International Court of Justice in 1955 to adjudicate between the territorial claims of Britain, Argentina and Chile. This proposal failed, as both Latin American countries rejected submitting to an international arbitration procedure.[110]

Negotiations towards the establishment of an international condominium over the continent first began in 1948, involving the 7 claimant powers (Britain, Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway, Chile and Argentina) and the US. This attempt was aimed at excluding the Soviet Union from the affairs of the continent and rapidly fell apart when the USSR declared an interest in the region, refused to recognize any claims of sovereignty and reserved the right to make its own claims in 1950.[110]

An important impetus toward the formation of the Antarctic Treaty System in 1959, was the International Geophysical Year, 1957–1958. This year of international scientific cooperation triggered an 18-month period of intense Antarctic science. More than 70 existing national scientific organizations then formed IGY committees, and participated in the cooperative effort. The British established Halley Research Station in 1956 by an expedition from the Royal Society. Sir Vivian Fuchs headed the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which completed the first overland crossing of Antarctica in 1958. In Japan, the Japan Maritime Safety Agency offered ice breaker Sōya as the South Pole observation ship and Showa Station was built as the first Japanese observation base on Antarctica.

France contributed with Dumont d'Urville Station and Charcot Station in Adélie Land. The ship Commandant Charcot of the French Navy spent nine months of 1949/50 at the coast of Adelie Land, performing ionospheric soundings.[111] The US erected the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station as the first permanent structure directly over the South Pole in January 1957.[112]

Finally, to prevent the possibility of military conflict in the region, the United States, United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and 9 other countries with significant interests negotiated and signed the Antarctic Treaty in 1959. The treaty entered into force in 1961 and sets aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve, established freedom of scientific investigation and banned military activity on that continent. The treaty was the first arms control agreement established during the Cold War.[113]

Recent history

In May 1965, the American physicist Carl R. Disch went missing during the course of his routine research near Byrd Station, Antarctica. His body was never found.[114]

A baby, named Emilio Marcos de Palma, was born near Hope Bay on 7 January 1978, becoming the first baby born on the continent. He also was born farther south than anyone in history.[115]

On 28 November 1979, an Air New Zealand DC-10 on a sightseeing trip crashed into Mount Erebus on Ross Island, killing all 257 people on board.[116]

In 1991 a convention among member nations of the Antarctic Treaty on how to regulate mining and drilling was proposed. Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke and French Prime Minister Michel Rocard led a response to this convention that resulted in the adoption of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, now known as the Madrid Protocol. All mineral extraction was banned for 50 years and the Antarctic was set aside as a "natural reserve, devoted to peace and science".[117]

Børge Ousland, a Norwegian explorer, finished the first unassisted Antarctic solo crossing on 18 January 1997.

On 23 November 2007, the MV Explorer struck an iceberg and sank, but all on board were rescued by nearby ships, including a passing Norwegian cruise ship, the MS Nordnorge.

In 2010, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory was completed.[118] In 2013, it was reported that the observatory had detected 28 neutrinos that originated outside the Solar system,[119]

Women in Antarctica

Women were originally kept from exploring Antarctica until well into the 1950s. A few pioneering women visited the Antarctic land and waters prior to the 1950s and many women requested to go on early expeditions, but were turned away.[120] Early pioneers such as Louise Séguin[121] and Ingrid Christensen were some of the first women to see Antarctic waters.[122] Christensen was the first woman to set foot on the mainland of Antarctica.[122] The first women to have any fanfare about their Antarctic journeys were Caroline Mikkelsen who set foot on an island of Antarctica in 1935,[123] and Jackie Ronne and Jennie Darlington who were the first women to over-winter in Antarctica in 1947.[124] The first woman scientist to work in Antarctica was Maria Klenova in 1956.[125] Silvia Morella de Palma was the first woman to give birth in Antarctica, delivering 3.4 kg (7 lb 8 oz) Emilio Palma at the Argentine Esperanza base 7 January 1978.

Women faced legal barriers and sexism that prevented most from visiting Antarctica and doing research until the late 1960s. The United States Congress banned American women from traveling to Antarctica until 1969.[126] Women were often excluded because it was thought that they could not handle the extreme temperatures or crisis situations.[127] The first woman from the British Antarctic Survey to go to Antarctica was Janet Thomson in 1983 who described the ban on women as a "rather improper segregation."[128][129]

Once women were allowed in Antarctica, they still had to fight against sexism and sexual harassment.[130][131] However, a tipping point was reached in the mid-1990s when it became the new normal that women were part of Antarctic life.[132] Women began to see a change as more and more women began working and researching in Antarctica.[133]

See also

- Colonization of Antarctica

- Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

- History of Livingston Island

- History of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- List of Russian explorers

- Research stations in Antarctica

- Timeline of women in Antarctica

- Ui-te-Rangiora, a Polynesian navigator who may have reached or sighted Antarctica

- Women in Antarctica

References

- "Meteorologica Book II 5". Archived from the original on 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- Wehi, Priscilla M.; Scott, Nigel J.; Beckwith, Jacinta; Pryor Rodgers, Rata; Gillies, Tasman; Van Uitregt, Vincent; Krushil, Watene (2021). "A short scan of Māori journeys to Antarctica". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 52 (5): 1–12. doi:10.1080/03036758.2021.1917633.

- Laura Geggel (15 June 2021). "Antarctica was likely discovered 1 100 years before Westerners 'found' it". Live Science. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- Smith, Stephenson Percy (1899). Hawaiki: the whence of the Maori, being an introduction to Rarotongan history: Part III. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, Volume 8. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- Hīroa, Te Rangi (1964). Vikings of the Sunrise. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited. pp. 116–117. Archived from the original on 2021-09-02. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- Anderson, A (2021). "On the improbability of pre-European Polynesian voyages to Antarctica: a response to Priscilla Wehi and colleagues". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 52 (5): 599–605. doi:10.1080/03036758.2021.1973517. S2CID 239089356. Archived from the original on 2021-10-17. Retrieved 2021-12-26.

- Anderson, A (2021). "A southern Māori perspective on stories of Polynesian polar voyaging". Polar Record. 57. doi:10.1017/S0032247421000693. S2CID 244118774. Archived from the original on 2021-12-26. Retrieved 2021-12-26.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Mill, Hugh Robert (1911). "Polar Regions § Antarctic Region". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Barr, William (2014). "Review of OF MAPS AND MEN: THE MYSTERIOUS DISCOVERY OF ANTARCTICA". Arctic. 67 (3): 410–411. doi:10.14430/arctic4411. JSTOR 24363785.

- Pinochet de la Barra, Óscar (November 1944). La Antártica Chilena. Editorial Andrés Bello.

- Calamari, Andrea (June 2022). "El conjurado que gobernó la Antártida" (in Spanish). Jot Down. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- "Pedro Sancho de la Hoz" (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- "1544" (in Spanish). Biografía de Chile. Archived from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- Barros Arana, Diego. "Capítulo XI". Historia general de Chile (in Spanish). Vol. Tomo cuarto (Digital edition based on the second edition of 2000 ed.). Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. p. 280. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- Lane, Kris E. (1998). Pillaging the Empire: Piracy in the Americas 1500–1750. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-76560-256-5. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Kock, Robbert. "Dutch in Chile". Colonial Voyage.com. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- Dalrymple, Alexander. (1771). A Collection of Voyages Made to the Ocean Between Cape Horn and Cape of Good Hope. Two volumes. London.

- Headland, Robert K. (1984). The Island of South Georgia, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25274-1

- Cook, James. (1777). A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World. Performed in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Adventure, In the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. In which is included, Captain Furneaux's Narrative of his Proceedings in the Adventure during the Separation of the Ships Archived 2011-09-16 at the Wayback Machine. Volume II. London: Printed for W. Strahan and T. Cadell. (Relevant fragment)

- Olaya, Vicente G. (2019-06-16). "Una cuarta misión buscará en el Polo Sur al 'San Telmo'". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Archived from the original on 2019-07-27. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

- Xin, Zhang (2010). Be careful, Here is Antarctica - the statistics and analysis of the grave accidents in Antarctica (PGCert). University of Canterbury. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Zarankin, Andrés; Senatore, María Ximena (2005). "Archaeology in Antarctica: Nineteenth-Century Capitalism Expansion Strategies". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 9 (1): 43–56. doi:10.1007/s10761-005-5672-y. ISSN 1092-7697. S2CID 55849547. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (España) (1987). Comunicaciones presentadas en el Primer Symposium Español de Estudios Antárticos: celebrado en Palma de Mallorca del 30 de junio al 4 de julio de 1985 (in Spanish). CSIC Press. ISBN 978-84-00-06530-0. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Cazenave de la Roche, Arnaud (2019). "Pesquisas sobre el descubrimiento de la Antártida: tras la estela del Williams of Blyth y del San Telmo (1819-1821)". Magallánica: Revista de historia moderna (in Spanish). 6 (11): 276–317. hdl:10261/245877. ISSN 2422-779X. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- Martín-Cancela (9 March 2018). Tras las huellas del San Telmo: contexto, historia y arqueología en la Antártida (in Spanish). Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. ISBN 978-84-17358-23-5. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- "The Discovery of Antarctica". www.coolantarctica.com. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- Erki Tammiksaar (14 December 2013). "Punane Bellingshausen" [Red Bellingshausen]. Postimees. Arvamus. Kultuur (in Estonian).

- Alan Gurney, Below the Convergence: Voyages Toward Antarctica, 1699–1839, Penguin Books, New York, 1998. p. 181

- The History of Antarctica: From Ancient Origins To Heroic

- "Charles Wilkes". South-Pole.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-20. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- M. R. A. Thomson (1977). "An Annotated Bibliography Of The Paleontology Of Lesser Antarctica And The Scotia Ridge". N.Z. Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 20 (5): 865–904. doi:10.1080/00288306.1977.10420686.

- "Hero: A New Antarctic Research Ship". PalmerStation.com. 1968. Archived from the original on 2017-05-28. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- "ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION—CHRONOLOGY". Quark Expeditions. 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

- Antarctic Circle—Antarctic First Archived 2006-02-08 at the Wayback Machine. Antarctic-circle.org. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- Fogg, G.E. (2000). The Royal Society and the Antarctic. London, The Royal Society: Notes and Records of the Royal Society London, Vol. 54, No. 1.

- Harrowfield, Richard (2004). Polar Castaways: The Ross Sea Party of Sir Ernest Shackleton, 1914–1917. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-77-357245-4.

- Barczewski, pp. 19–20. (Barczewski mentions a figure of 14 expeditions)

- Matthew Jarron, Independent & Individualist: Art in Dundee 1867-1924 (Dundee, 2015) chapter 7

- Murray, John (1894). The Renewal of Antarctic Exploration. London: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1.

- Crane, David (2005). Scott of the Antarctic: A Life of Courage, and Tragedy in the Extreme South. London: Harper Collins. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-00-715068-7.

- American Association for the Advancement of Science (1887). The Exploration of the Antarctic Regions. New York: Science, Vol. 9, No. 223.

- "Henrik Bull". Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- Borchgrevink, Carstens (1901). First on the Antarctic Continent. George Newnes Ltd. ISBN 978-0-90-583841-0. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2008. pp. 9–10

- Borchgrevink, Carstens (1901). First on the Antarctic Continent. George Newnes Ltd. ISBN 978-0-90-583841-0. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 11 August 2008. pp. 4–5

- Carsten Borchgrevink (1901). First on the Antarctic continent: being an account of the British Antarctic expedition, 1898–1900. London: G. Newnes.

- Jones, Max (2003). The Last Great Quest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-01-9280-483-9.

- "Mountaineering and Polar Collection – Antarctica". National Library of Scotland. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- "Antarctic Explorers – Adrien de Gerlache". South-pole.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- Huntford (Last Place on Earth) pp. 64–75

- R. K. Headland (1989). Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780521309035. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- "The Forgotten Expedition". Antarctic Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 20 November 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- Borchgrevink, Carsten Egeberg (1864–1934). Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Edition. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- Preston, pp. 57–79

- Crane, p. 253 (map); pp. 294–95 (maps)

- Fiennes, p. 89

- "Scotland and the Antarctic, Section 5: The Voyage of the Scotia". Glasgow Digital Library. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Speak, pp. 82–95

- "William S. Bruce". South-Pole.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-19. Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- "Scotland and the Antarctic, Section 3: Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen". Glasgow Digital Library. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2008.

- Riffenburgh, pp. 309–12 (summary of achievements)

- Huntford (Shackleton biography) p. 242 (map)

- "Erich von Drygalski 1865–1949". South-pole.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Mill, pp. 420–24

- Crane, p. 307

- Goodlad, James A. "Scotland and the Antarctic, Section II: Antarctic Exploration". Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- "Otto Nordenskiöld 1869–1928". South-pole.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Barczewski, p. 90

- Mills, William James (11 December 2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57-607422-0. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2008. pp. 135–139

- "Jean-Baptiste Charcot". South-pole.com. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2008.(Francais voyage)

- Mill, pp. 431–32

- "Jean-Baptiste Charcot". South-pole.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2008.(Pourquoispas? voyage)

- Amundsen, Vol I pp. 184–95; Vol II, pp. 120–134

- Huntford (Last Place on Earth), pp. 446–74

- "Roald Amundsen". Norwegian Embassy (UK). Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Explorer and leader: Captain Scott". National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- National Research Council (U.S.), Polar Research Board (1986). Antarctic Treaty System: An assessment. National Academies. p. 96. ISBN 9780309036405. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

- Shackleton, Ernest Henry (1919). South: The Story of Shackleton's 1914–1917 Expedition.

- Tyler-Lewis, Kelly (2007). The Lost Men. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 193–197. ISBN 978-0-74-757972-4.

- Huntford, Roland (1985). Shackleton. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 684. ISBN 978-03-4025-007-5.

- Althoff, William F. Drift Station: Arctic outposts of superpower science. Potomac Books Inc., Dulles, Virginia. 2007. p. 35.

- Wilkins, Hubert Wilkins. Flying the Arctic. p. 313.

- "Milestones, Jan. 28, 1980". Time. 28 January 1980. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Historic Names — Norwegian-American Scientific Traverse of East Antarctica Archived 2008-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. Traverse.npolar.no. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- Navy Military History Archived 2013-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. History.navy.mil. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- "Friends of Ferguson Heritage- The Worst Journey in the World". www.fofh.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "1544" (in Spanish). Biografía de Chile. Archived from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2022-08-25.

- Francisco Orrego Vicuña; Augusto Salinas Araya (1977). Desarrollo de la Antártica (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Instituto de Estudios Internacionales, Universidad de Chile; Editorial Universitaria. Archived from the original on 2022-08-19. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Prieto Larrain, M. Cristina (2004). "El Tratado Antártico, vehículo de paz en un campo minado". Revista Universum (in Spanish). University of Talca. 19 (1): 138–147. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- International law for Antarctica, p. 652 Archived 2023-03-25 at the Wayback Machine, Francesco Francioni and Tullio Scovazzi, 1996

- http://www.legislation.govt.nz/regulation/imperial/1923/0974/latest/DLM1195.html Archived 2022-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Order in Council Under the British Settlements Act, 1887 (50 & 51 Vict c 54), Providing for the Government of the Ross Dependency.

- Antarctica and international law: a collection of inter-state and national documents, Volume 2. pp. 143. Author: W. M. Bush. Editor: Oceana Publications, 1982. ISBN 0-379-20321-9, ISBN 978-0-379-20321-9

- C2004C00416 / Australian Antarctic Territory Acceptance Act 1933 ( Cth )

- Dunmore, John (2007). From Venus to Antarctica: The Life of Dumont D'Urville. Auckland: Exisle Publ. p. 209. ISBN 9780908988716.

- "A Brief History of Mawson". Australian Government - Australian Arctic Division. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- Kyvik, Helga, ed. (2008). Norge i Antarktis. Oslo: Schibsted Forlag. p. 52. ISBN 978-82-516-2589-0.

- "Lov om Bouvet-øya, Peter I's øy og Dronning Maud Land m.m. (bilandsloven)" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "Dronning Maud Land" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 21 July 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Gjeldsvik, Tore. "Dronning Maud Land". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Widerøe, Turi (2008). "Annekteringen av Dronning Maud Land". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- Murphy, 2002, p. 192.

- Murphy, 2002, p. 204.

- "Forutsetninger for Antarktistraktaten". Norsk Polarhistorie (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Escude, Carlos; Cisneros, Andres. "Historia General de las Relaciones Exteriores de la Republica Argentina" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- Kieran Mulvaney (2001). At the Ends of the Earth: A History of the Polar Regions. Island Press. pp. 124–130. ISBN 9781559639088.

- "About - British Antarctic Survey". www.antarctica.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge » Picture Library catalogue". www.spri.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Antarctica and the Arctic: the complete encyclopedia, Volume 1, by David McGonigal, Lynn Woodworth, page 98

- Bertrand, Kenneth J. (1971). Americans in Antarctica 1775–1948. New York: American Geographical Society.

- Kearns, David A. (2005). "Operation Highjump: Task Force 68". Where Hell Freezes Over: A Story of Amazing Bravery and Survival. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 304. ISBN 978-0-312-34205-0. Retrieved 2011-05-31.

- Klaus Dodds (2012). The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191633515.

- M. Barré, K. Rawer: "Quelques résultats d’observations ionosphériques effectuées près de la Terre Adélie". Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics volume 1, issue 5–6 (1951), pp. 311–314.

- "South Pole's first building blown up after 53 years". OurAmazingPlanet.com. 2011-03-31. Archived from the original on 2020-06-05. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- "ATS - Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty". www.ats.aq. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- "Scientist Missing from Byrd Station Presumed Dead". Bulletin of the United States Antarctic Projects Office. U.S. Antarctic Projects Office. 6 (6): 2. April 1965. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- antarctica.org Archived 2007-10-06 at the Wayback Machine—Science: in force...

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 ZK-NZP Mount Erebus". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 2019-04-24. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- "Bob Hawke: There is not one outstanding leader in the world". Sydney Morning Herald. 2016-07-08. Archived from the original on 2016-07-21. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- "IceCube Neutrino Observatory". Archived from the original on 2015-01-12. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- IceCube Collaboration (2013). "Evidence for High-Energy Extraterrestrial Neutrinos at the IceCube Detector". Science. 342 (6161): 1242856. arXiv:1311.5238. Bibcode:2013Sci...342E...1I. doi:10.1126/science.1242856. PMID 24264993. S2CID 27788533.

- Blackadder, Jesse (2015). "Frozen Voices: Women, Silence and Antarctica" (PDF). In Hince, Bernadette; Summerson, Rupert; Wiesel, Arnan (eds.). Antarctica: Music, Sounds, and Cultural Connections. Canberra: ANU Press. p. 90. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-06-02. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- Hulbe, Christina L.; Wang, Weili; Ommanney, Simon (2010). "Women in Glaciology, a Historical Perspective" (PDF). Journal of Glaciology. 56 (200): 947. Bibcode:2010JGlac..56..944H. doi:10.3189/002214311796406202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 November 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- Blackadder 2015, p.172

- "Women in Antarctica: Sharing this Life-Changing Experience" Archived 2012-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, transcript of speech by Robin Burns, given at the 4th Annual Phillip Law Lecture; Hobart, Tasmania, Australia; 18 June 2005. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- "Antarctic Firsts". Antarctic Circle. 4 October 2014. Archived from the original on 8 February 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Bogle, Ariel (11 August 2016). "New Wikipedia Project Champions Women Scientists in the Antarctic". Mashable. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Davis, Amanda (14 April 2016). "This IEEE Fellow Blazed a Trail for Female Scientists in Antarctica". The Institute. Archived from the original on 26 July 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- Hament, Ellyn. "A Warmer Climate for Women in Antarctica". Origins Antarctica: Scientific Journeys from McMurdo to the Pole. Exploratorium. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Brueck, Hilary (13 February 2016). "Meet the All-Women Team heading to Antarctica This Year". Forbes. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- "Janet Thomson: An 'Improper Segregation of Scientists' at the British Antarctic Survey". Voices of Science. British Library. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- Dean, Cornelia (10 November 1998). "After a Struggle, Women Win A Place 'on the Ice'; In Labs and in the Field, a New Outlook". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Satchell, Michael (5 June 1983). "Women Who Conquer the South Pole (continued)". The San Bernardino County Sun. Archived from the original on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- Rejcek, Peter (13 November 2009). "Women Fully Integrated Into USAP Over Last 40 Years". The Antarctic Sun. United States Antarctic Program. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Marler, Regina (2005). "Ice Queen". Advocate (952): 77. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2016 – via EBSCOhost.

Further reading

- "Working-Class Hero". Portland Magazine. 8 November 2012. — "'She’s just moored there at the dock in Bay Center, sitting in the mud,' says Charles Lagerbom, Northport, Maine, resident and president of the Antarctican Society".

- The South Pole; an account of the Norwegian Antarctic expedition in the "Fram," 1910–12 — Volume 1 and Volume 2 at Project Gutenberg

- The Worst Journey in the World, Volumes 1 and 2 Antarctic 1910–1913 at Project Gutenberg

- South: the story of Shackleton's 1914–1917 expedition at Project Gutenberg

- Anthony, Jason C. (2012). Hoosh: roast penguin, scurvy day, and other stories of Antarctic cuisine. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2666-1.

- Robert Clancy, John Manning, Henk Brolsma: Mapping Antarctica: A Five Hundred Year Record of Discovery. Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-94-007-4320-5 [Print]; ISBN 978-94-007-4321-2 [eBook]

- Ivanov, L. General Geography and History of Livingston Island. In: Bulgarian Antarctic Research: A Synthesis. Eds. C. Pimpirev and N. Chipev. Sofia: St. Kliment Ohridski University Press, 2015. pp. 17–28. ISBN 978-954-07-3939-7

.svg.png.webp)