Maryland campaign

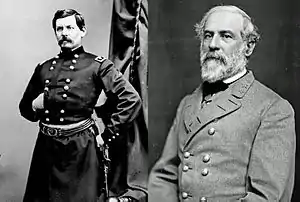

The Maryland campaign (or Antietam campaign) occurred September 4–20, 1862, during the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's first invasion of the North was repulsed by the Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who moved to intercept Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia and eventually attacked it near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The resulting Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history.

| Maryland campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Union General George B. McClellan and Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the principal commanders of the campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 102,234[1][2] | 55,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

28,272 total (2,783 killed; 12,108 wounded; 13,381 captured/missing)[3][4] |

16,229 total (3,812 killed; 10,591 wounded; 1,826 captured/missing)[5] | ||||||

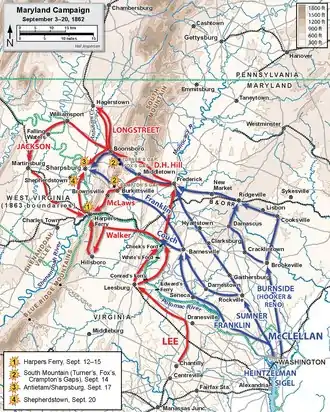

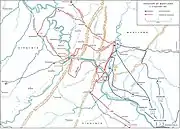

Following his victory in the northern Virginia campaign, Lee moved north with 55,000 men through the Shenandoah Valley starting on September 4, 1862. His objective was to resupply his army outside of the war-torn Virginia theater and to damage Northern morale in anticipation of the November elections. He undertook the risky maneuver of splitting his army so that he could continue north into Maryland while simultaneously capturing the Federal garrison and arsenal at Harpers Ferry. McClellan accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders to his subordinate commanders and planned to isolate and defeat the separated portions of Lee's army.

While Confederate Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured Harpers Ferry (September 12–15), McClellan's army of 102,000 men attempted to move quickly through the South Mountain passes that separated him from Lee. The Battle of South Mountain on September 14 delayed McClellan's advance and allowed Lee sufficient time to concentrate most of his army at Sharpsburg. The Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg) on September 17 was the bloodiest day in American military history with over 22,000 casualties. Lee, outnumbered two to one, moved his defensive forces to parry each offensive blow, but McClellan never deployed all of the reserves of his army to capitalize on localized successes and destroy the Confederates. On September 18, Lee ordered a withdrawal across the Potomac and on September 19–20, fights by Lee's rear guard at Shepherdstown ended the campaign.

Although Antietam was a tactical draw, it meant the strategy behind Lee's Maryland campaign had failed. President Abraham Lincoln used this Union victory as the justification for announcing his Emancipation Proclamation, which effectively ended any threat of European support for the Confederacy.

Background

Military situation

The year 1862 started out well for Union forces in the Eastern Theater. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac had invaded the Virginia Peninsula during the Peninsula Campaign and by June stood only a few miles outside the Confederate capital at Richmond. But, when Robert E. Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1, fortunes reversed. Lee fought McClellan aggressively in the Seven Days Battles; McClellan lost his nerve, and his army retreated down the Peninsula. Lee then conducted the northern Virginia campaign in which he outmaneuvered and defeated Maj. Gen. John Pope and his Army of Virginia, most significantly at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas). Lee's Maryland campaign can be considered the concluding part of a logically connected, three-campaign, summer offensive against Federal forces in the Eastern Theater.[6]

The Confederates had suffered significant manpower losses in the wake of the summer campaigns. Nevertheless, Lee decided his army was ready for a great challenge: an invasion of the North. His goal was to reach the major Northern states of Maryland and Pennsylvania, and cut off the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line that supplied Washington, D.C. His movements would threaten Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, so as to "annoy and harass the enemy."[7]

Several motives led to Lee's decision to launch an invasion. First, he needed to supply his army and knew the farms of the North had been untouched by war, unlike those in Virginia. Moving the war northward would relieve pressure on Virginia. Second was the issue of Northern morale. Lee knew the Confederacy did not have to win the war by defeating the North militarily; it merely needed to make the Northern populace and government unwilling to continue the fight. With the Congressional elections of 1862 approaching in November, Lee believed that an invading army playing havoc inside the North could tip the balance of Congress to the Democratic Party, which might force Abraham Lincoln to negotiate an end to the war. He told Confederate President Jefferson Davis in a letter of September 3 that the enemy was "much weakened and demoralized."[8]

There were secondary reasons as well. The Confederate invasion might be able to incite an uprising in Maryland, especially given that it was a slave-holding state and many of its citizens held a sympathetic stance toward the South. Some Confederate politicians, including Jefferson Davis, believed the prospect of foreign recognition for the Confederacy would be made stronger by a military victory on Northern soil, but there is no evidence that Lee thought the South should base its military plans on this possibility. Nevertheless, the news of the victory at Second Bull Run and the start of Lee's invasion caused considerable diplomatic activity between the Confederate States and France and the United Kingdom.[9] Additionally, generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith in the Western Theatre outmaneuvered Don Carlos Buell to reach the border state of Kentucky from eastern Tennessee through the Battle of Richmond which coincided with Confederate victories in the East.

After the defeat of Pope at Second Bull Run, President Lincoln reluctantly returned to the man who had mended a broken army before—George B. McClellan, who had done it after the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas). He knew that McClellan was a strong organizer and a skilled trainer of troops, able to recombine the units of Pope's army with the Army of the Potomac faster than anyone, and there was no other viable choice for the job except Burnside, who was asked and declined command of the army. On September 2, Lincoln named McClellan to command "the fortifications of Washington, and all the troops for the defense of the capital."[10] The appointment was controversial in the Cabinet, a majority of whom signed a petition declaring to the president "our deliberate opinion that, at this time, it is not safe to entrust to Major General McClellan the command of any Army of the United States."[11] The president admitted that it was like "curing the bite with the hair of the dog." But Lincoln told his secretary, John Hay, "We must use what tools we have. There is no man in the Army who can man these fortifications and lick these troops of ours into shape half as well as he. If he can't fight himself, he excels in making others ready to fight."[12]

Opposing forces

Union

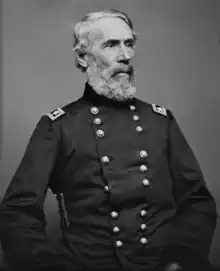

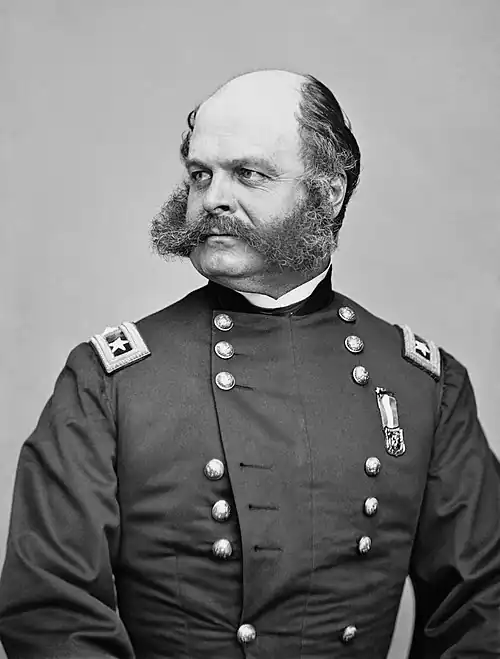

| Union corps commanders |

|---|

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac, bolstered by units absorbed from John Pope's Army of Virginia, included six infantry corps, about 102,000 men.[1][13]

- The I Corps, under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Gens. Rufus King, James B. Ricketts, and George G. Meade.

- The II Corps, under Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gens. Israel B. Richardson and John Sedgwick, and Brig. Gen. William H. French.

- The V Corps, under Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gen. George W. Morell, Brig. Gen. George Sykes, and Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys.

- The VI Corps, under Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gens. Henry W. Slocum and William F. "Baldy" Smith, and a division from the IV Corps under Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch.

- The IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Gens. Orlando B. Willcox, Samuel D. Sturgis, and Isaac P. Rodman, and the Kanawha Division, under Brig. Gen. Jacob D. Cox.

- The XII Corps, under Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Gens. Alpheus S. Williams and George S. Greene, and the cavalry division of Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton.

During the march north into Maryland, McClellan changed his army's command structure, appointing commanders for three "wings": the left, commanded by William B. Franklin, consisted of his own VI Corps plus the division of Darius Couch; the center, under Edwin Sumner, consisted of his II Corps and the XII Corps; the right, under Ambrose Burnside, consisted of his IX Corps (temporarily commanded by Maj. Gen. Jesse L. Reno until he was killed at South Mountain) and the I Corps. This wing organization was revoked just before the start of the Battle of Antietam.[14]

The army that McClellan took into Maryland was not an entirely cohesive or battle-ready fighting force. At its core were the Peninsula veterans of the II, V, and VI Corps, but a large portion of the army were untested rookie regiments or troops who had never fought as part of the Army of the Potomac. Some of the rookies had never even loaded their muskets, and others were unknowingly armed with defective weapons.

The "core" Army of the Potomac, the II, III, V, and VI Corps, which had served through the Peninsula Campaign, were the easiest ones to get ready for action. In addition there were the three corps that had comprised Pope's army. Aside from the Pennsylvania Reserves, which had born the brunt of action in the Seven Days Battles, none of these troops had served under McClellan before, all had been poorly led, and did not have much record of battlefield success. The two divisions of Burnside's IX Corps were also new to McClellan, but they had served capably in North Carolina early in the year. The IX Corps was also being joined by Brig. Gen Jacob D. Cox's "Kanawah" division from West Virginia, new to McClellan as well. These troops had seen no major action so far and were essentially green.

The I Corps had excellent troops; as mentioned above the Pennsylvania Reserves had been in the thick of the Seven Days Battles and all three divisions were heavily engaged at Second Bull Run. McDowell however had been written off as a loser, he was despised by his own troops and would not hold a command in the Civil War again. McClellan's first choice to lead the I Corps was his friend and intimate Jesse Reno, then having operational command of the IX Corps but instead the position went to Joe Hooker, considered a more experienced officer.

The XII Corps under Nathaniel Banks had a poor reputation; it had been badly defeated by "Stonewall" Jackson's troops during the Valley Campaign in spring, had fought poorly at Cedar Mountain, and Pope held the corps and Banks in such low regard that he kept them away from the Second Bull Run battlefield. Banks was dropped from command of the XII Corps and eventually sent to Louisiana. Brig. Gen Alpheus Williams temporarily commanded the corps until Joseph Mansfield assumed command on September 14.

The III Corps and XI Corps had both suffered severe losses at Second Bull Run and were almost driven from the field in panic; they were left behind in Washington, D.C., to rest and refit. The III Corps were excellent troops who had fought hard on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run, while the XI Corps, consisting of a large number of German-American troops, as well as its commander Maj. Gen Franz Sigel had a poor reputation and no record of success on the battlefield.

McClellan was thus able to use his influence to remove several underperforming generals, namely McDowell, Heintzelman, and Banks; the Army of the Potomac in this regard was a little behind its Confederate opponent as Lee had been able to purge his ranks of inadequate generals in the aftermath of the Seven Days Battles. The administration had wanted to remove Porter and Franklin, whom they considered politically suspect, but McClellan was able to retain them for this campaign.

Of the six corps that participated in the Maryland campaign, the II and VI were the largest and most well-rested as neither had fought since the Seven Days Battles. The II Corps received a new division of nine month troops commanded by Brig. Gen William French and the VI Corps had one new regiment; all the rest of the men in both corps had fought on the Peninsula. The I Corps was the smallest, as it had suffered heavy losses at Second Bull Run (one of its divisions had also been heavily engaged in the Seven Days) and would lose still more men at South Mountain; it is estimated that the corps had 8,000 men at Antietam out of a paper strength of 14,000. The VI Corps was also joined by Darius Couch's division, formerly part of Erasmus Keyes's IV Corps, and now being brought up from the Virginia Peninsula.

The V Corps was heavily engaged in the Seven Days Battles and at Second Bull Run, and had lost significant amounts of men; several new regiments of green troops would replace them. A new division of nine month regiments led by Brig. Gen Andrew A. Humphreys was added, but they would not arrive until after Antietam.

The IX Corps had had two divisions at Second Bull Run (commanded by General Reno as Burnside was not present at the battle); for the Maryland campaign, it was joined by a third division under Brig. Gen Samuel Sturgis and Brig. Gen Jacob Cox's "Kanawah" Division, on loan from the West Virginia area. It included several green regiments and the corps as a whole was quite inexperienced as Second Bull Run had been the only serious engagement it had fought in.

The XII Corps had not fought at Second Bull Run and its last engagement had been at Cedar Mountain a month earlier; some men from this corps were left in the Washington defenses and swapped for a number of green regiments. After Nathaniel Banks was fired on September 12, the senior division commander, Alpheus Williams, commanded the corps for a few days until Maj. Gen Joseph K. Mansfield, an old regular army officer with 40 years of service, was named to command.

Confederate

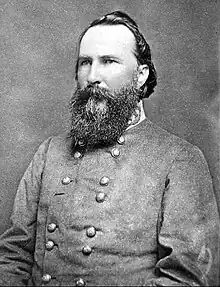

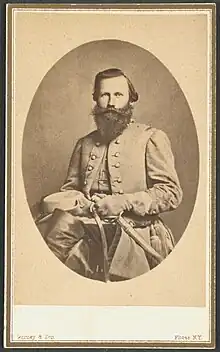

| Confederate corps commanders |

|---|

General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia was organized into two large infantry corps, about 55,000 effectives at the beginning of September.[15]

The First Corps, under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson, Brig. Gen. David R. Jones, Brig. Gen. John G. Walker, Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood, and an independent brigade under Brig. Gen. Nathan G. "Shanks" Evans.

The Second Corps, under Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, consisted of the divisions of Brig. Gen. Alexander R. Lawton, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill (the Light Division), Brig. Gen. John R. Jones, and Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill.

The remaining units were the Cavalry Corps, under Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, and the reserve artillery, commanded by Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton. The Second Corps was organized with artillery attached to each division, in contrast to the First Corps, which reserved its artillery at the corps level.

One of the more unusual aspects of the Maryland campaign was the severely understrength condition of the Army of Northern Virginia. Robert E. Lee had commanded nearly 90,000 men in it when he assumed command of the army in June, but the Seven Days Battles cost him 20,000 casualties and the northern Virginia campaign another 12,000 or so. Along with the marching into Maryland, the manpower of the army dropped even more due to straggling, lack of food, and a significant number of soldiers in Virginia regiments deserting on the grounds that they had signed up to defend their state and not invade the North. Significant numbers of Confederate soldiers had no shoes and were unable to handle the macadamized roads of Maryland. Lee may have had under 40,000 men on the field at Antietam, the smallest and most ragged his army would be until the final days of the Petersburg Siege. Many brigades were the size of regiments, their regiments company-sized. Despite the ragged condition of the army, morale was high and almost all of the Confederates were veterans, which put them at an advantage over the numerous green Union regiments.

The divisions of McLaws and D.H. Hill had been left in the Richmond area during the northern Virginia campaign; they quickly rejoined the army for the march into Maryland. Lee was also reinforced by Brig. Gen John G. Walker's two-brigade division from North Carolina.

The exact size of the Army of Northern Virginia at Antietam has been a source of debate since the 19th century since no army returns were made between July 20 and September 22. "Lost Cause" propagandists during the postwar years presented a picture of Lee being severely understrength and possibly having as few as 30,000 men on the field. Union generals and veterans of the war generally believed that the Army of Northern Virginia was not that small on September 17, and estimated Confederate strength as high as 50,000 men. It seems almost certain that the most exhausted and understrength Confederate divisions were Lawton's and the Stonewall Division, as both had been fighting and marching since May almost without a break. Other Confederate divisions such as D.H. Hill's, had not fought since the Peninsula and would have been better rested and more physically fit. The lack of food was a serious problem for the Army of Northern Virginia, as most crops were a month away from harvesting in September and many soldiers were forced to subsist on field corn and green apples, which gave them indigestion and diarrhea. As noted above, malnutrition was greatest in the two divisions of Jackson's old Valley Army due to months of unbroken fighting and marching.

Initial movements

On September 3, just two days after the Battle of Chantilly, Lee wrote to President Davis that he had decided to cross into Maryland unless the president objected. On the same day, Lee began shifting his army north and west from Chantilly towards Leesburg, Virginia. On September 4, advance elements of the Army of Northern Virginia crossed into Maryland from Loudoun County. The main body of the army advanced into Frederick, Maryland, on September 7. The 55,000-man army had been reinforced by troops who had been defending Richmond—the divisions of Maj. Gens. D.H. Hill and Lafayette McLaws and two brigades under Brig. Gen. John G. Walker—but they merely made up for the 9,000 men lost at Bull Run and Chantilly.[16]

Lee's invasion coincided with another strategic offensive by the Confederacy. Generals Braxton Bragg and Edmund Kirby Smith had simultaneously launched invasions of Kentucky.[17] Jefferson Davis sent to all three generals a draft public proclamation, with blank spaces available for them to insert the name of whatever state their invading forces might reach. Davis wrote to explain to the public (and, indirectly, the European Powers) why the South seemed to be changing its strategy. Until this point, the Confederacy had claimed it was the victim of aggression and was merely defending itself against "foreign invasion." Davis explained that the Confederacy was still waging a war of self-defense. He wrote there was "no design of conquest," and that the invasions were only an aggressive effort to force the Lincoln government to let the South go in peace. "We are driven to protect our own country by transferring the seat of war to that of an enemy who pursues us with a relentless and apparently aimless hostility."[18]

Davis's draft proclamation did not reach his generals until after they had issued proclamations of their own. They stressed that they had come as liberators, not conquerors, to these border states, but they did not address the larger issue of the Confederate strategy shift as Davis had desired. Lee's proclamation announced to the people of Maryland that his army had come "with the deepest sympathy [for] the wrongs that have been inflicted upon the citizens of the commonwealth allied to the States of the South by the strongest social, political, and commercial ties ... to aid you in throwing off this foreign yoke, to enable you again to enjoy the inalienable rights of freemen."[19]

Dividing Lee's army

Lee divided his army into four parts as it moved into Maryland. After receiving intelligence of militia activity in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Lee sent Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to Boonsboro and then to Hagerstown. (The intelligence overstated the threat since only 20 militiamen were in Chambersburg at the time.)[20] Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson was ordered to seize the Union arsenal at Harpers Ferry with three separate columns. This left only the thinly spread cavalry of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart and the division of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill to guard the army's rear at South Mountain.[21]

The specific reason Lee chose this risky strategy of splitting his army to capture Harpers Ferry is not known. One possibility is that he knew it commanded his supply lines through the Shenandoah Valley. Before he entered Maryland he had assumed that the Federal garrisons at Winchester, Martinsburg, and Harpers Ferry would be cut off and abandoned without firing a shot (and, in fact, both Winchester and Martinsburg were evacuated).[22] Another possibility is that it was simply a tempting target with many vital supplies but virtually indefensible.[20] McClellan requested permission from Washington to evacuate Harpers Ferry and attach its garrison to his army, but his request was refused.[23]

Reactions to invasion

Lee's invasion was fraught with difficulties from the beginning. The Confederate Army's numerical strength suffered in the wake of straggling and desertion. Although he started from Chantilly with 55,000 men, within 10 days this number had diminished to 45,000.[24] Some troops refused to cross the Potomac River because an invasion of Union territory violated their beliefs that they were fighting only to defend their states from Northern aggression. Countless others became ill with diarrhea after eating unripe "green corn" from the Maryland fields or fell out because their shoeless feet were bloodied on hard-surfaced Northern roads.[22] Lee ordered his commanders to deal harshly with stragglers, whom he considered cowards "who desert their comrades in peril" and were therefore "unworthy members of an army that has immortalized itself" in its recent campaigns.[25]

Upon entering Maryland, the Confederates found little support; rather, they were met with reactions that ranged from a cool lack of enthusiasm, to, in most cases, open hostility. Robert E. Lee was disappointed at the state's resistance, a condition that he had not anticipated. Although Maryland was a slaveholding state, Confederate sympathies were considerably less pronounced among the lower and middle classes, which generally supported the Union cause, than among the pro-secession legislature, the majority of the members of which hailed from Southern Maryland, an area almost entirely economically dependent on slave labor. Furthermore, many of the fiercely pro-Southern Marylanders had already traveled south at the beginning of the war to join the Confederate Army in Virginia. Only a "few score" of men joined Lee's columns in Maryland.[26]

Maryland and Pennsylvania, alarmed and outraged by the invasion, rose at once to arms. Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin called for 50,000 militia to turn out, and he nominated Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, a native Pennsylvanian, to command them. (This caused considerable frustration to McClellan and Reynolds's corps commander, Joseph Hooker, but general-in-chief Henry W. Halleck ordered Reynolds to serve under Curtin and told Hooker to find a new division commander.) As far north as Wilkes-Barre, church and courthouse bells rang out, calling men to drill.[27]

In Maryland, panic was much more widespread than in Pennsylvania, which was not yet immediately threatened. Baltimore, which Lee incorrectly regarded as a hotbed of secession merely waiting for the appearance of Confederate armies to revolt, took up the war call against him immediately.[28]

When it was learned in Baltimore that Southern armies had crossed the Potomac River, the reaction was one of instantaneous hysteria followed quickly by stoic resolution. Crowds milled in the street outside newspaper offices waiting for the latest bulletins, and the sale of liquor was halted to restrain the excitable. The public stocked up on food and other essentials, fearing a siege. Philadelphia was also sent into a flurry of frenzied preparations, despite being over 150 miles (240 km) from Hagerstown and in no immediate danger.[29]

McClellan's pursuit

I did not believe before coming here that there was so much Union feeling in the state. ... The whole population [of Frederick] seemed to turn out to welcome us. When Genl McClellan came thro[ugh] the ladies nearly eat him up, they kissed his clothing, threw their arms around his horse's neck and committed all sorts of extravagances.

Brig. Gen. John Gibbon[30]

McClellan moved out of Washington starting on September 7 with his 87,000-man army in a lethargic pursuit.[31] He was a naturally cautious general and assumed he would be facing over 120,000 Confederates. He also was maintaining running arguments with the government in Washington, demanding that the forces defending the capital city report to him.[32] The army started with relatively low morale, a consequence of its defeats on the Peninsula and at Second Bull Run, but upon crossing into Maryland, their spirits were boosted by the "friendly, almost tumultuous welcome" that they received from the citizens of the state.[33]

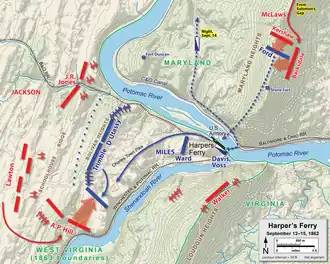

Although he was being pursued at a leisurely pace by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and the Union Army of the Potomac, outnumbering him more than two to one, Lee chose the risky strategy of dividing his army to seize the prize of Harpers Ferry. While the corps of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet drove north in the direction of Hagerstown, Lee sent columns of troops to converge and attack Harpers Ferry from three directions. The largest column, 11,500 men under Jackson, was to recross the Potomac and circle around to the west of Harpers Ferry and attack it from Bolivar Heights, while the other two columns, under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws (8,000 men) and Brig. Gen. John G. Walker (3,400), were to capture Maryland Heights and Loudoun Heights, commanding the town from the east and south.[34]

The Army of the Potomac reached Frederick, Maryland, on September 13. There, Cpl. Barton Mitchell of the 27th Indiana Infantry discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed campaign plans of Lee's army—Special Order 191—wrapped around three cigars. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically, thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail. Upon realizing the intelligence value of this discovery, McClellan threw up his arms and exclaimed, "Now I know what to do!" He waved the order at his old Army friend, Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, and said, "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobbie Lee, I will be willing to go home." He telegraphed President Lincoln: "I have the whole rebel force in front of me, but I am confident, and no time shall be lost. I think Lee has made a gross mistake, and that he will be severely punished for it. I have all the plans of the rebels, and will catch them in their own trap if my men are equal to the emergency. ... Will send you trophies." McClellan waited 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence. His delay squandered the opportunity to destroy Lee's army.[35]

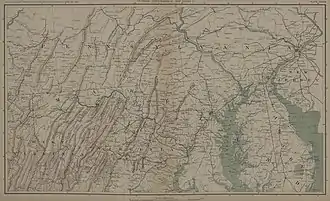

On the night of September 13, the Army of the Potomac moved toward South Mountain, with Burnside's right wing of the army directed to Turner's Gap, and Franklin's left wing to Crampton's Gap. South Mountain is the name given to the continuation of the Blue Ridge Mountains after they enter Maryland. It is a natural obstacle that separates the Shenandoah Valley and Cumberland Valley from the eastern part of Maryland. Crossing the passes of South Mountain was the only way to reach Lee's army.[36]

Lee, seeing McClellan's uncharacteristic aggressive actions, and possibly learning through a Confederate sympathizer that his order had been compromised,[37] quickly moved to concentrate his army. He chose not to abandon his invasion and return to Virginia yet, because Jackson had not completed the capture of Harpers Ferry. Instead, he chose to make a stand at Sharpsburg, Maryland. In the meantime, elements of the Army of Northern Virginia waited in defense of the passes of South Mountain.[38]

Battles of the Maryland campaign

Harpers Ferry

As Jackson's three columns approached Harpers Ferry, Col. Dixon S. Miles, Union commander of the garrison, insisted on keeping most of the troops near the town instead of taking up commanding positions on the surrounding heights. The South Carolinians under Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw encountered the slim defenses of the most important position, Maryland Heights, but only brief skirmishing ensued. Strong attacks by the brigades of Kershaw and William Barksdale on September 13 drove the mostly inexperienced Union troops from the heights.[39]

During the fighting on Maryland Heights, the other Confederate columns arrived and were astonished to see that critical positions to the west and south of town were not defended. Jackson methodically positioned his artillery around Harpers Ferry and ordered Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill to move down the west bank of the Shenandoah River in preparation for a flank attack on the Federal left the next morning. By the morning of September 15, Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland Heights and at the base of Loudoun Heights. He began a fierce artillery barrage from all sides and ordered an infantry assault. Miles realized that the situation was hopeless and agreed with his subordinates to raise the white flag of surrender. Before he could surrender personally, he was mortally wounded by an artillery shell and died the next day. Jackson took possession of Harpers Ferry and more than 12,000 Union prisoners, then led most of his men to join Lee at Sharpsburg, leaving Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill's division to complete the occupation of the town.[40]

South Mountain

.jpg.webp)

Pitched battles were fought on September 14 for possession of the South Mountain passes: Crampton's, Turner's, and Fox's Gaps. Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill defended Turner's and Fox's Gaps against Burnside. To the south, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws defended Crampton's Gap against Franklin, who was able to break through at Crampton's Gap, but the Confederates were able to hold Turner's and Fox's, if only precariously. (For the counter argument that the Union held Fox's Gap, see Older, Curtis L., Hood's Defeat Near Fox's Gap September 14, 1862.)[41] Lee realized the futility of his position against the numerically superior Union forces, and he ordered his troops to Sharpsburg. McClellan was then theoretically in a position to destroy Lee's army before it could concentrate. McClellan's limited activity on September 15 after his victory at South Mountain, however, condemned the garrison at Harpers Ferry to capture and gave Lee time to unite his scattered divisions at Sharpsburg.[42]

Antietam (Sharpsburg)

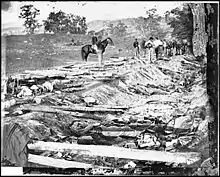

On September 16, McClellan confronted Lee near Sharpsburg. Lee was defending a line to the west of Antietam Creek. At dawn on September 17, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's I Corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee's left flank that began the bloody battle. Attacks and counterattacks swept across the Miller Cornfield and the woods near the Dunker Church as Maj. Gen. Joseph K. Mansfield's XII Corps joined to reinforce Hooker. Union assaults against the Sunken Road ("Bloody Lane") by Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's II Corps eventually pierced the Confederate center, but the Federal advantage was not pressed. In the afternoon, Burnside's IX Corps crossed a stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolled up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.P. Hill's division arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside's men and saving Lee's army from destruction. Although outnumbered two to one, Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in only four of his six available corps. This enabled Lee to shift brigades across the battlefield and counter each individual Union assault. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties—Union 12,401, or 25%; Confederate 10,316, or 31%—Lee continued to skirmish with McClellan throughout September 18, while transporting his wounded men south of the Potomac. McClellan did not renew the offensive. After dark, Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw across the Potomac into the Shenandoah Valley.[43]

Shepherdstown

On September 19, a detachment of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter's V Corps pushed across the river at Boteler's Ford, attacked the Confederate rear guard commanded by Brig. Gen. William N. Pendleton, and captured four guns. Early on September 20, Porter pushed elements of two divisions across the Potomac to establish a bridgehead. A.P. Hill's division counterattacked while many of the Federals were crossing and nearly annihilated the 118th Pennsylvania (the "Corn Exchange" Regiment), inflicting 269 casualties. This rearguard action discouraged further Federal pursuit.[44]

Aftermath and diplomatic implications

Lee successfully withdrew across the Potomac, ending the Maryland campaign and summer campaigning altogether. President Lincoln was disappointed in McClellan's performance. He believed that the general's cautious and poorly coordinated actions in the field had forced the battle to a draw rather than a crippling Confederate defeat. He was even more astonished that from September 17 to October 26, despite repeated entreaties from the War Department and the president, McClellan declined to pursue Lee across the Potomac, citing shortages of equipment and the fear of overextending his forces. General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck wrote in his official report, "The long inactivity of so large an army in the face of a defeated foe, and during the most favorable season for rapid movements and a vigorous campaign, was a matter of great disappointment and regret."[45] Lincoln relieved McClellan of his command of the Army of the Potomac on November 7, effectively ending the general's military career. Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside rose to command the Army of the Potomac. The Eastern Theater was relatively quiet until December, when Lee faced Burnside at the Battle of Fredericksburg.[46]

Although a tactical draw, the Battle of Antietam was a strategic victory for the Union. It forced the end of Lee's strategic invasion of the North and gave Abraham Lincoln the victory he was awaiting before announcing the Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, which took effect on January 1, 1863. Although Lincoln had intended to do so earlier, he was advised by his Cabinet to make this announcement after a Union victory to avoid the perception that it was issued out of desperation. The Confederate reversal at Antietam also dissuaded the governments of France and Great Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. And, with the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, it became less likely that future battlefield victories would induce foreign recognition. Lincoln had effectively highlighted slavery as a tenet of the Confederate States of America, and the abhorrence of slavery in France and Great Britain would not allow for intervention on behalf of the South.[47]

The Union lost 28,272 men during the Maryland campaign (2,783 killed, 12,108 wounded, 13,381 missing).[48]

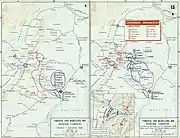

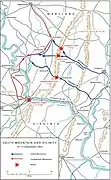

Maryland campaign, actions September 7 to 13, 1862 (Additional map 1)

Maryland campaign, actions September 7 to 13, 1862 (Additional map 1) Maryland campaign, actions September 3 to 13, 1862 (Additional map 2)

Maryland campaign, actions September 3 to 13, 1862 (Additional map 2) Maryland campaign, actions September 14 to 15, 1862 (Additional map 3)

Maryland campaign, actions September 14 to 15, 1862 (Additional map 3)

See also

Notes

- V Corps (Porter): 21,000; I, II, VI, IX, XII Corps + Cav. Div.: 74,234; 3rd Div./V Corps: 7,000; Total Union strength: 102,234

Further information: Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, p. 67, 374 and Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 2, p. 264. - See Maryland campaign: Opposing forces

- Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, p. 204

- Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, p. 549

- 10,291 Confederate casualties: 1,567 killed and 8,724 wounded for the entire Maryland campaign. See: Official Records, Series I, Volume XIX, Part 1, pp. 810–13.

- Eicher, pp. 268–334; McPherson, pp. 30–34, 44–47, 80–86.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 65-66; Esposito, text for map 65; Eicher, pp. 336–37.

- McPherson, pp. 89–92; Glatthaar, p. 164; Eicher, p. 337.

- McPherson, pp. 91–94; Eicher, p. 337.

- Rafuse, p. 268; McPherson, pp. 86–87.

- Sears, McClellan, p. 260.

- Bailey, Bloodiest Day, p. 15.

- 84,000 according to Eicher, p. 338.

- Sears, Landscape, p. 102.

- Eicher, p. 337; O.R. Series 1, Vol. XIX part 2 (S# 28), p. 621; Luvaas and Nelson, pp. 294–300; Esposito, map 67; Sears, Landscape, pp. 366–72. Although most histories, including the Official Records, refer to these organizations as Corps, that designation was not formally made until November 6, after the Maryland campaign. Longstreet's unit was referred to as the Right Wing, Jackson's the Left Wing, for most of 1862. (Gen. Lee referred in official correspondence to these as "commands". See, for instance, Luvaas and Nelson, p. 4.) Harsh, Sounding the Shallows, pp. 32–90, states that D.H. Hill was temporarily in command of a "Center Wing" with his own division (commanded initially by Brig. Gen. Roswell S. Ripley, and the divisions of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws and Brig. Gen. John G. Walker. The other references list him strictly as a division commander.

- Sears, Landscape, p. 69.

- McPherson, p. 75; Sears, Landscape, p. 63. The word invasion has been used historically for these operations, and in the case of Kentucky it is valid. The Confederacy was attempting to regain territory it believed was its own. In the case of Maryland, however, Lee had no plans to seize and hold Union territory, and therefore his actions would more properly be described as a strategic raid or an incursion.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 68–69.

- McPherson, p. 91; Sears, Landscape, pp. 68–69.

- Eicher, p. 339

- Bailey, p. 38.

- Sears, Landscape, p. 83.

- Rafuse, pp. 285–86.

- McPherson, p. 100.

- Glatthaar, p. 167; Esposito, map 65; McPherson, p. 100.

- McPherson, p. 98; Glatthaar, p. 166; Eicher, p. 339.

- McPherson, p. 101.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 99–100.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 100–01.

- McPherson, p. 105.

- Eicher, p. 339.

- Esposito, map 65; Eicher, p. 340.

- McPherson, pp. 104–05.

- Bailey, p. 39.

- Sears, Landscape, p. 113; Glatthaar, p. 168; Eicher, p. 340; Rafuse, pp. 291–93; McPherson, pp. 108–09.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 82–83; Eicher, p. 340.

- Sears, Landscape, pp. 350–52. General Lee made no reference to the lost order in his 1862 reports, and it was not until 1863, after McClellan had published his own report, that Lee acknowledged the circumstances of McClellan's intelligence find. However, in interviews after the war, he mentioned the Confederate sympathizer who had supposedly witnessed McClellan reading the order. Discovery of these interviews prompted Douglas Southall Freeman to include this information in his 1946 Lee's Lieutenants (a revised view from his 1934 work, the four volume biography of Lee), which has led to citations in subsequent sources. Sears argues that "there is substantial evidence that in this instance Lee's memory failed him" and that the "conclusion seems inescapable that Lee learned from the Maryland civilian only that the Federal army had suddenly become active" and nothing more.

- Esposito, map 56; Rafuse, p. 295; Eicher, p. 341.

- McPherson, p. 109; Esposito, map 66; Eicher, pp. 344–49.

- Eicher, pp. 345–47; Glatthaar, p. 168; Esposito, map 56; McPherson, p. 110.

- Older, Curtis L., Hood's Defeat Near Fox's Gap September 14, 1862, Kindle and Apple Books.

- Eicher, pp. 341–44; McPherson, pp. 111–12; Esposito, map 66.

- McPherson, pp. 116–31; Esposito, maps 67–69; Eicher, pp. 348–63.

- Eicher, p. 363.

- Bailey, p. 67.

- McPherson, pp. 150–53; Esposito, map 70; Eicher, pp. 382–83.

- McPherson, pp. 138–39, 146–49; Eicher, pp. 365–66.

- "MGen McClellan's Official Reports". Antietam.aotw.org. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

References

- Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8094-4740-1.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-684-82787-2.

- Harsh, Joseph L. Sounding the Shallows: A Confederate Companion for the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-87338-641-8.

- Luvaas, Jay, and Harold W. Nelson, eds. Guide to the Battle of Antietam. U.S. Army War College Guides to Civil War Battles. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1987. ISBN 0-7006-0784-6.

- McPherson, James M. Crossroads of Freedom: Antietam, The Battle That Changed the Course of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-513521-0.

- Older, Curtis L., Hood's Defeat Near Fox's Gap September 14, 1862. Kindle and Apple Books. ISBN 978-0-9960067-5-0.

- Rafuse, Ethan S. McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle for the Union. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-253-34532-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon. New York: Da Capo Press, 1988. ISBN 0-306-80913-3.

- Sears, Stephen W. Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. ISBN 0-89919-172-X.

- Wolff, Robert S. "The Antietam Campaign." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- National Park Service battle descriptions

Memoirs and primary sources

- Dawes, Rufus R. A Full Blown Yankee of the Iron Brigade: Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8032-6618-9. First published 1890 by E. R. Alderman and Sons.

- Douglas, Henry Kyd. I Rode with Stonewall: The War Experiences of the Youngest Member of Jackson's Staff. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940. ISBN 0-8078-0337-5.

- "Brady's Photographs: Pictures of the Dead at Antietam". New York Times. New York. October 20, 1862.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Ballard, Ted. Battle of Antietam: Staff Ride Guide. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 2006. OCLC 68192262.

- Cannan, John. The Antietam Campaign: August–September 1862. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994. ISBN 0-938289-91-8.

- Carman, Ezra Ayers. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862. Vol. 1, South Mountain. Edited by Thomas G. Clemens. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2010. ISBN 978-1-932714-81-4.

- Carman, Ezra Ayers. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862: Ezra A. Carman's Definitive Account of the Union and Confederate Armies at Antietam. Edited by Joseph Pierro. New York: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 0-415-95628-5.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. Counter-thrust: From the Peninsula to the Antietam. Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-1515-3.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Antietam: Essays on the 1862 Maryland Campaign. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87338-400-8.

- Harsh, Joseph L. Confederate Tide Rising: Robert E. Lee and the Making of Southern Strategy, 1861–1862. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-87338-580-2.

- Harsh, Joseph L. Taken at the Flood: Robert E. Lee and Confederate Strategy in the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-87338-631-0.

- Hartwig, H. Scott., To Antietam Creek: The Maryland Campaign of 1862. Baltimore MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4214-0631-2.

- Jamieson, Perry D. Death in September: The Antietam Campaign. Abilene, TX: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1999. ISBN 1-893114-07-4.

- Murfin, James V. The Gleam of Bayonets: The Battle of Antietam and the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965. ISBN 0-8071-0990-8.

- Orrison, Robert, and Kevin R. Pawlak. To Hazard All: A Guide to the Maryland Campaign, 1862. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2018. ISBN 978-1-61121-409-3.

- Perry D. Jamieson and Bradford A. Wineman, The Maryland and Fredericksburg Campaigns, 1862–1863. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 2015. CMH Pub 75-6.

- Older, Curtis L. Hood's Defeat Near Fox's Gap September 14, 1862. Kindle and Apple Books. ISBN 978-0-9960067-5-0.

External links

- The Battle of Antietam: Battle Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Battle of Antietam Animated Map (Civil War Trust)

- Antietam National Battlefield Park

- Antietam on the Web

- Atlas of the battlefield of Antietam (Library of Congress).

- Animated history of the Battle of Antietam

- Official Reports from Antietam

- Official Records: The Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg),"the bloodiest day of the Civil War" (September 17, 1862)

- USS Antietam

- Collection of pictures by Alexander Gardner

- Online transcription of 1869 record of original Confederate Burials in Washington County, Maryland, including Antietam Battlefield {Washington County Maryland Free Library-for reference only}

- History of Antietam National Cemetery, including a descriptive list of all the loyal soldiers buried therein, published 1869

- Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light Sept 1862, first edition after the Battle of Antietam

- Brotherswar.com The Battle of Antietam

- Map of North America and American Civil War at time of the Battle of Antietam at omniatlas.com