Impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson

The impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson, 17th president of the United States, was held in the United States Senate and concluded with acquittal on three of eleven charges before adjourning sine die without a verdict on the remaining charges. It was the first impeachment trial of a U.S. president and was the sixth federal impeachment trial in U.S. history. The trial began March 5, 1868, and adjourned on May 26.

| Impeachment trial of Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) President Johnson's Senate impeachment trial, illustrated by Theodore R. Davis in Harper's Weekly | |

| Date | March 5, 1868– May 26, 1868 (2 months and 3 weeks) |

| Accused | Andrew Johnson (president of the United States) |

| Presiding officer | Salmon P. Chase (chief justice of the United States) |

| House managers: |

|

| Defense counsel: | |

| Outcome | Acquitted by the U.S. Senate, remained in office |

| Charges | Eleven high crimes and misdemeanors |

| Cause | Violating the Tenure of Office Act by attempting to replace Edwin Stanton as secretary of war while Congress was not in session and other alleged abuses of presidential power |

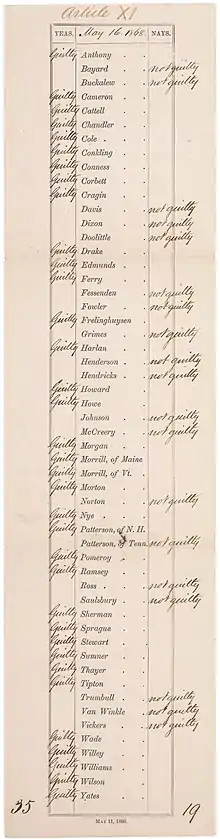

| Accusation | Article XI |

| Votes in favor | 35 "guilty" |

| Votes against | 19 "not guilty" |

| Result | Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) |

| Accusation | Article II |

| Votes in favor | 35 "guilty" |

| Votes against | 19 "not guilty" |

| Result | Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) |

| Accusation | Article III |

| Votes in favor | 35 "guilty" |

| Votes against | 19 "not guilty" |

| Result | Acquitted (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) |

| Motion | Motion to adjourn sine die |

| Votes in favor | 33 |

| Votes against | 17 |

| Result | Motion passed |

| The Senate held a roll call vote on only 3 of the 11 articles before adjourning as a court. | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

16th Vice President of the United States

17th President of the United States

Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

Family

|

||

The trial was held after the United States House of Representatives impeached Johnson on February 24, 1868. In the eleven articles of impeachment adopted in early March 1868, the House had chiefly charged Johnson with violating the 1867 Tenure of Office Act by attempting to remove Secretary of War Edwin Stanton from office and name Lorenzo Thomas secretary of war ad interim.

During the trial, the prosecution offered by the impeachment managers that the House had appointed argued that Johnson had explicitly violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing Stanton without the consent of the Senate. The managers contended that United States presidents were obligated to carry out and honor the laws passed by the United States Congress, regardless of whether the president believed them to be constitutional. The managers argued that, otherwise, presidents would be allowed to regularly disobey the will of Congress (which they argued, as elected representatives, represented the will of the American people).

Johnson's defense both questioned the criminality of the alleged offenses and raised doubts about Johnson's intent. One of the points made by the defense was that ambiguity existed in the Tenure of Office Act that left open a vagueness as to whether it was actually applicable to Johnson's firing of Stanton. They also argued that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and that Johnson's intent in firing Stanton had been to test the constitutionality of the law before the Supreme Court of the United States (and that Johnson was entitled to do so). They further argued that, even if the law were constitutional, that presidents should not be removed from office for misconstruing their constitutional rights. They further argued that Johnson was acting in interest of the necessity of keeping the Department of War functional by appointing Lorenzo Thomas as an interim officer, and that he had caused no public harm in doing so. They also argued that the Republican Party was using impeachment as a political tool. The defense asserted the view that presidents should not be removed from office by impeachment for political misdeeds, as this is what elections were meant for.

The trial resulted in acquittal, with the Senate voting identically on three of the eleven articles of impeachment, failing each time by a single vote to reach the supermajority needed to convict Johnson. On each of those three articles, thirty-five Republican senators voted to convict, while ten Republican senators and all nine Democratic senators voted to acquit. After those three votes all failed to result in a conviction, the Senate then adjourned the trial without voting on the remaining eight articles of impeachment. The majority decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in its 1926 Myers v. United States decision later opined in dictum that the Tenure of Office Act at the center of the impeachment had been a constitutionally invalid law.

Background

Andrew Johnson ascended to the United States presidency after the 1865 assassination of Republican president Abraham Lincoln. Johnson, a Southern Democrat, had been elected vice president in 1864 on a unity ticket with Lincoln.[1] As president, Johnson held open disagreements with the Republican majority of the United States House and Senate (the two chambers of the United States Congress).

Johnson's conflict with the Republican-controlled Congress led to a number of efforts being taken since 1866, particularly by Radical Republicans, to impeach Johnson. On January 7, 1867, the House of Representatives voted to launch of an impeachment inquiry run by the House Committee on the Judiciary, which resulted in a November 25, 1867 5–4 vote by the committee to recommend impeachment. However, on December 7, 1867, vote, the full House rejected impeachment by a 108–57 vote.[2][3][4][5] On January 22, 1868, the House approved by a vote of 103–37 a resolution launching a second impeachment inquiry run by House Select Committee on Reconstruction.[6]

In 1867, Congress had passed the Tenure of Office Act and enacted it by successfully overriding Johnson's veto. The law was written with the intent of both curbing Johnson's power and protecting United States Secretary of War Edwin Stanton from being removed from his office unilaterally by Johnson.[7][8] Stanton was strongly aligned with the Radical Republicans, and acted as an executive branch ally to the Reconstruction policies of the congressional Radical Republicans.[9][10] The Tenure of Office Act restricted the power of the United States president to suspend Senate-confirmed federal branch officers while the Senate was not in session.[11] The Tenure of Office Act was put in place to prevent the president from dismissing an officer that had been previously appointed with the advice and consent of the Senate without the Senate's approval to remove them.[12] Per the law, if the president dismissed such an officer when the Senate was in recess, and the Senate voted upon reconvening against ratifying the removal, the president would be required to reinstate the individual.[11] Johnson, during a Senate recess in August 1867, suspended Stanton pending the next session of the Senate and appointed Ulysses S. Grant as acting secretary of war.[13] When the Senate convened on January 13, 1868, it refused to ratify the removal by a vote of 35–6.[14] However, disregarding this vote, on February 21, 1868, President Johnson attempted to replace Stanton with Lorenzo Thomas in an apparent violation of the Tenure of Office Act.[15][7]

The same day that Johnson attempted to replace Stanton with Thomas, a one-sentence resolution to impeach Johnson, written by John Covode (R– PA), was referred to the House Select Committee on Reconstruction.[16][17][18] On February 22, the House Select Committee on Reconstruction released a report which recommended Johnson be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors, and also reported an amended version of the impeachment resolution.[19][20] On February 24, the House of Representatives voted 126–47 to impeach Johnson for "high crimes and misdemeanors", which were detailed in 11 articles of impeachment (the 11 articles were separately approved in votes held on March 2 and March 3, 1868).[21][22][23] The primary charge against Johnson was that he had violated the Tenure of Office Act by removing Stanton from office.[21]

Johnson's was the first impeachment trial of a United States president.[24] It was also only the sixth federal impeachment trial in American history, after the impeachment trials of William Blount, John Pickering, Samuel Chase, James H. Peck, and West Hughes Humphreys.[25] In only two of the previous impeachment trials had the Senate voted to convict.[14]

In the United States' federal impeachment trials, if an incumbent officeholder is convicted by a vote of two-thirds of the Senate, they are automatically removed from office. The Senate can, only after voting to convict, vote by a simple majority to additionally bar the convicted individual from holding federal office in the future.[26][27][28][29]

Summary of the articles of impeachment

Both the first eight articles and the eleventh article adopted in the House related to Johnson violating the Tenure of Office Act by attempting to dismiss Secretary of War Stanton. In addition, several of these articles also accused Johnson of violating other acts, and the eleventh article also accused Johnson of violating his oath of office. The ninth article focused on an accusation that Johnson had violated the Command of Army Act, and the eleventh article reiterated this. The tenth article charged Johnson with attempting, "to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt, and reproach the Congress of the United States", but did not cite a clear violation of the law.[21][22][24][30]

The eleven articles presented the following charges:

- Article 1: That Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act in his February 21, 1868 order to remove Secretary of War Stanton[22]

- Article 2: That Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act by sending "a letter of authority" to Lorenzo Thomas regarding his appointment to be acting Secretary of War when there was, in fact, no legal vacancy, because Secretary Stanton had been removed in violation of the Tenure of Office Act[22]

- Article 3: That Johnson had violated the Tenure of Office Act by appointing Lorenzo Thomas to be acting Secretary of War when there was, in fact, no legal vacancy, because Secretary Stanton had been removed in violation of the Tenure of Office Act[22]

- Article 4: That Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act by conspiring with Lorenzo Thomas and others "unlawfully to hinder and prevent Edwin M. Stanton, then and there Secretary of the Department of War" from carrying out his duties[22]

- Article 5: That Johnson had conspired with Lorenzo Thomas and others to "prevent and hinder the execution" of the Tenure of Office Act[22]

- Article 6: That Johnson had violated both the Tenure of Office Act and An Act to Define and Punish Certain Conspiracies by conspiring with Lorenzo Thomas "by force to seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War" under control of Secretary Stanton in violation of, thereby committing a high crime in office[22]

- Article 7: That Johnson had violated both the Tenure of Office Act by conspiring with Lorenzo Thomas "by force to seize, take, and possess the property of the United States in the Department of War" under control of Secretary Stanton, thereby committing a high misdemeanor in office[22]

- Article 8: That Johnson had unlawfully sought "to control the disbursements of the moneys appropriated for the military service and for the Department of War", by moving to remove Secretary Stanton and appoint Lorenzo Thomas[22]

- Article 9: That Johnson had violated the Command of Army Act by unlawfully instructing Major General William H. Emory to ignore as unconstitutional the 1867 Army Appropriations Act language that all orders issued by the President and Secretary of War "relating to military operations ... shall be issued through the General of the Army"[21][22]

- Article 10: That Johnson had on numerous occasions, made "with a loud voice, certain intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues, and did therein utter loud threats and bitter menaces ... against Congress [and] the laws of the United States duly enacted thereby, amid the cries, jeers and laughter of the multitudes then assembled and within hearing"[22]

- Article 11: That Johnson had violated his oath of office to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed" by unlawfully and unconstitutionally challenging the authority of the 39th Congress to legislate due to unreconstructed southern states had not been readmitted to the Union; violated the Tenure of Office Act by removing Secretary of War Stanton; contrived to fail to execute the Command of Army Act, which directed that executive orders to the military were to be issued through the General of the Army; and prevented the execution of an act entitled "An act to provide for the more efficient government of the rebel states".[22][24][30]

Officers of the trial

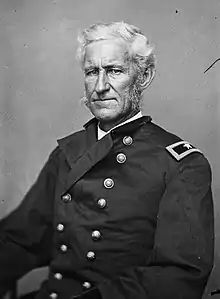

Salmon P. Chase as presiding officer

.jpg.webp)

Per the Constitution of the United States' rules on impeachment trials of incumbent presidents, Chief Justice of the United States Salmon P. Chase presided over the trial.[31]

Chase had his own personal objections to the impeachment itself. Chase was of the opinion that, in a presidential impeachment, the Senate truly sat as a court to try the president. Therefore, Chase believed that this meant any charge against a president in an impeachment needed to be legally sustained. He objected to the viewpoint common among Radical Republicans that an impeachment could be a merely political proceeding by a legislative body.[32] A difference in attitude between the prosecution and the defense as to whether impeachment was a political proceeding or a true court proceeding may be evidenced in the fact that the prosecution referred to Chase as "Mr. President" (seeing it as a political proceeding, and therefore viewing Chase as merely presiding over the Senate), while the defense referred to Chase as "Mr. Chief Justice" (viewing Chase as presiding over a court).[32][33]

While Chase had long been associated with more extremist elements of the Republican Party, Chase's conduct during the trial saw him receive condemnation from the Radical Republicans. Radical Republicans were the greatest critics of Chase's conduct during the trial, while Democrats, contrarily, strongly praised his conduct.[32]

House managers

.jpg.webp)

Top row L-R: Butler, Stevens, Williams, Bingham; bottom row L-R: Wilson, Boutwell, Logan

The House of Representatives appointed seven members to serve as House impeachment managers, equivalent to prosecutors. These seven members were John Bingham, George S. Boutwell, Benjamin Butler, John A. Logan, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams and James F. Wilson.[34]

It was at the request of the impeachment managers that a further two articles of impeachment were adopted by the House on May 3, the day after the committee was appointed, and the day after the initial nine articles of impeachment were adopted.[19][21]

| House managers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman of the House Committee of Impeachment Managers John Bingham (Republican, Ohio) |

George S. Boutwell (Republican, Massachusetts) |

Benjamin Butler (Republican, Massachusetts) |

John A. Logan (Republican, Illinois) | ||||

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

_(1).jpg.webp) | ||||

| Thaddeus Stevens (Republican, Pennsylvania) |

Thomas Williams (Republican, Pennsylvania) |

James F. Wilson (Republican, Iowa) |

|||||

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) | |||||

Selection of members

.png.webp)

The seven individuals to serve as impeachment managers had been selected by the House by ballot on March 2, 1868, after the initial nine articles of impeachment had been passed.[19]

The House Republican caucus had met March 1, 1868 (the previous night) to hold an internal vote to determine a consensus on who they would support to be impeachment managers. Barred from attending were independent Republican Samuel Fenton Cary of Ohio and "Conservative Republican" Thomas E. Stewart of New York,[35][36] both of whom had voted against impeachment (unlike the rest of the Republican caucus).[21] With 79 members present, the House Republican caucus held a vote, with the rules stating that those receiving the highest number of votes would be chosen, and that no person would be chosen unless they had received a minimum of 40 votes in their favor. The first ballot saw Boutwell receive 75 votes, Bingham 74 votes, Wilson 71 votes, Williams 66 votes, Butler 48 votes, and Logan 40, thus designating the six as having the support of the Republican caucus. Stevens and Thomas Jenckes (R– RI) had each received 37 votes on the first ballot, while several other congressmen received between two and ten votes. On the second ballot, Stevens received 41 votes, securing him the House Republican caucus' support to be an impeachment manager.[37]

Bingham was a leading Moderate Republican while Boutwell was a leading Radical Republican. Bingham served as chairman of the House Committee of Impeachment Managers.[38][39][40] He had past experience serving in such a role, having previously served as the chairman of impeachment managers for the impeachment of West Hughes Humphreys.[40] Stevens, another leading Radical Republican was passed over on the first ballot likely because many House members felt that the old and ailing Stevens lacked the strength needed to serve as an effective prosecutor. However, his relentless opposition to the president likely garnered him enough respect to receive enough votes on the second ballot. Benjamin Butler, who had only served in the House of Representatives for less than a year, was likely chosen for his breadth of experience practicing criminal law. The Chicago Tribune declared that, "Butler was one of the greatest criminal lawyers in the country," and jested that Johnson was, "the greatest criminal". The two other Radical Republicans selected as impeachment managers, Logan and Williams, were less obvious choices. While John Logan was a charismatic individual that had commanded the Grand Army of the Republic, he did not have a notable legal career and the House of Representatives was full of other individuals that had had legal careers of great note. Thomas Williams was considered a respected lawyer, but his level of expressed contempt for President Johnson was regarded as extreme. Additionally, only ten weeks before, at the close of the first impeachment inquiry against Johnson Williams had written a poorly constructed House Committee on the Judiciary majority report in favor of impeachment[38] that had failed to convince even a majority of Republicans to vote for impeachment in the December 1867 vote.[5]

For the March 2, 1868 official vote on impeachment managers, Speaker Colfax had made attempts to include a Democrat among those to act as tellers to count the ballots on this vote. But each time he appointed a Democrat as a teller, they declined to serve as one. Colfax had first appointed Samuel S. Marshall (D– IL). When Marshall had declined to serve, Colfax then appointed Samuel J. Randall (D– PA). When Randall too declined, Colfax appointed William E. Niblack (D–IN), only to have him also decline to serve. This left only members of the Republican Party as tellers. The tellers were Thomas Jenckes (R– RI), Luke P. Poland (R– VT), and Rufus P. Spalding (R– OH).[19] It was indicated that Democrats did not wish to participate in the selection of impeachment managers.[19] After the tellers were named, Luke P. Poland nominated Bingham, Boutwell, Butler, Logan, Stevens, Williams, and Wilson to serve as impeachment managers.[19] 118 House members cast votes on who should serve as impeachment managers.[19] No Democrats participated in the vote.[41] The seven individuals selected in the vote were those who received the most votes in favor of them as managers. A candidate needed to receive at least 60 votes in order to be elected. As seven individuals met this threshold, the vote only required a single round of balloting.[19]

Vote on impeachment managers

Vote on impeachment managers[19][36]

At least 60 votes needed to be electedParty Candidate Votes % Republican John Bingham 114 14.25 Republican George S. Boutwell 113 14.13 Republican James F. Wilson 112 14.00 Republican Benjamin Butler 108 13.50 Republican Thomas Williams 107 13.38 Republican John A. Logan 106 13.25 Republican Thaddeus Stevens 105 13.13 Republican Thomas Jenckes 22 2.75 Republican Luke P. Poland 3 0.38 Republican Glenni William Scofield 3 0.38 Republican Godlove Stein Orth 2 0.25 Republican John F. Benjamin 1 0.13 Republican Austin Blair 1 0.13 Republican John C. Churchill 1 0.13 Republican John A. Peters 1 0.13 Republican Charles Upson 1 0.13 Total votes 800 100

Designation of a chairman

When Speaker Schuyler Colfax initially read the results of the balloting, he read Stevens and Butler's names first, seeming to imply that Stevens would serve as the committee's chairman while Butler would be his deputy. Bingham furiously exclaimed, "I'll be damned if I serve under Butler."[38] Likely to sidestep this problem, Speaker Colfax decided to announce that the committee itself would choose who would serve as its chairman, as opposed to the full House deciding.[19][38] Boutwell had originally been chosen as the chairman of impeachment managers for Johnson's impeachment trial, but, before the trial, resigned this position in favor of having Bingham serve in it.[40] Despite Bingham being carrying this title, it was Benjamin Butler who ultimately would step up to act as the lead prosecutor. Despite Thaddeus Stevens having been a major force behind the effort to impeach Johnson, he could not be the leading force of the prosecution due to his poor health at the time of the trial, which prevented him from attending many of the meetings of the impeachment managers. Despite not being the official chairman, Butler effectively served as the lead prosecutor during the trial.[38]

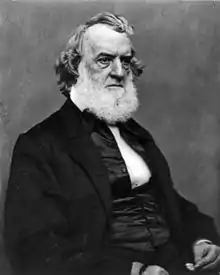

Johnson's counsel

.jpg.webp)

The president's defense team was made up of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, William M. Evarts, William S. Groesbeck, Thomas Amos Rogers Nelson, and Henry Stanbery.[24][42] Stanbery had resigned as United States attorney general on March 12, 1868, in order to devote all of his time to serving on Johnson's defense team.[24][43] The members of Johnson's defense team were all well-known and well-esteemed as lawyers.[24]

Originally also to be part of the defense team was Jeremiah S. Black.[44] Black was originally to act as Johnson's chief counsel for the trial, but he withdrew due to differences with Johnson.[14][45]

| President's counsel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benjamin Robbins Curtis (former associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States) |

William M. Evarts | William S. Groesbeck (former member of the United States House of Representatives) |

Thomas Amos Rogers Nelson (former member of the United States House of Representatives) |

Henry Stanbery (United States attorney general -resigned as attorney general on March 12, 1868) | ||

.png.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

_(1).jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) |

.jpg.webp) | ||

Pretrial

Senate informed of the impeachment (February 25)

On the morning of February 25, 1868, the Senate was informed by Congressmen John Bingham and Thaddeus Stevens that Johnson had been impeached and that articles of impeachment would be created.[24][46][47]

Bingham and Stevens delivered a message reading,

By order of the House of Representatives we appear at the bar of the Senate, and in the name of the House of Representatives, and of all the people of the United States, we do impeach Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, of high crimes and misdemeanors in office; and we do further inform the Senate that the House of Representatives will, in due time, exhibit particular articles of impeachment against him, and make good the same; and in their name we do demand that the Senate take order for the appearance of the said Andrew Johnson to answer to said impeachment.[47]

Senate select committee to consider and report on the message of the House

The Senate referred the message it received from Bingham and Stevens to a purposely created select committee.[47][48] The committee was created on February 25 after the adoption of a resolution introduced by Jacob M. Howard (R– NH). After the resolution creating the special committee was created, Howard was appointed to the committee, along with Senators Roscoe Conkling (R– NY), George F. Edmunds (R– VT), Reverdy Johnson (D– MD), Oliver P. Morton (R– IN), Samuel C. Pomeroy (R– KY), Lyman Trumbull (R– IL).[49] The next day, Howard reported from the committee a resolution declaring that the Senate was ready to receive the articles of impeachment. This resolution was adopted by the Senate through unanimous consent.[47][48][49][50]

Development of rules for trial (February 25–March 2)

The Senate proceeded to develop a set of rules for the trial and its officers.[31] The select committee appointed on February 25 were tasked with developing the rules to be used.[49][32][25] The select committee was chaired by Senator Jacob M. Howard (R–MI).[51] On February 28, the proposed new rules of procedure in impeachment trials was reported to the Senate by select committee member Howard.[24][49][50] The Senate adopted the new rules for impeachment trials on March 2, 1868.[24][49]

The first two impeachment trials in United States history (those of William Blount and John Pickering) had each had their own individual set of rules. The nineteen rules established for the trial of Samuel Chase appear also to have been used for the trials of James H. Peck and West Hughes Humphreys.[25] However, the exact language of the rules used for previous trials could not be utilized for the Johnson impeachment, as those rules used wording specific to a trial being presided over by an officer of the Senate (as had been the case for all previous impeachment trials), while the Constitution stipulates that impeachments trials for incumbent presidents are presided over by the chief justice of the United States.[52]

The select committee sought to create permanent rules that would be used for any future impeachments, declaring it to be, "proper to report general rules for the trial of all impeachments". Indeed, the rules adopted in 1868 have, with very few changes, remained the rules for impeachment trials ever since.[25][53] The select committee came forward with a recommendation of twenty-five rules, many of which were versions of the rules adopted for Chase's trial, and some others which codified practices from the other previous trials.[25] The twenty-five rules were quickly debated and adopted.[24] During the trial, disputes arose about the interpretations of the rules, and this lead the Senate to agree to three changes to the rules to better clarify their intent.[25]

Chief Justice Chase had voiced objection to the Senate drafting their rules prior to being convened as a court of impeachment.[32] On March 4, 1868, Chase sent the Senate a message which expressed his legal conclusions that, contrary to the conclusions reached by the Senate, rules for the government proceedings of the court of impeachment should only be framed when the Senate is formally convened as a court of impeachment, that articles of impeachment should only be presented to the Senate once it had formally convened as a court of impeachment, and that no summons or other process should be issued outside of the formal court of impeachment.[49]

Articles of impeachment presented to Senate (March 4)

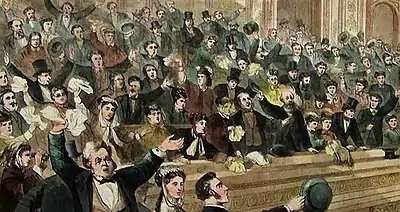

.jpg.webp)

On March 3, 1868, the Senate received a message delivered by Clerk of the United States House of Representatives Edward McPherson informing them of the House's appointment of impeachment managers, and that the managers had been directed to bring the articles of impeachment to the Senate and exhibit them to the Senate.[49] On March 4, 1868, amid tremendous public attention and press coverage, the eleven articles of impeachment were presented to the Senate.[24][31] At 1pm, Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate George T. Brown announced the presence of the impeachment managers at the door of the Senate chamber. Senator Benjamin Wade (R–OH), the president pro tempore of the Senate, then requested the managers take the seats assigned to them within the Senate's bar. Then Wade had the sergeant at arms make the proclacmation,

Hear ye! Hear ye! Hear ye! All persons are commanded to keep silence, on pain of imprisonment, while the House of Representatives is exhibiting to the Senate of the United States articles of impeachment against Andrew Johnson, President of the United States.[47]

Then, Bingham read the articles of impeachment. After the articles of impeachment were read, a resolution was adopted resolving to have the Senate meet at 1pm the next day to begin the trial, with the swearing-in of senators as jurors to be administered at that time by the chief justice. It also resolved that, once senators were seated as jurors, the Senate would receive the impeachment managers. The adoption of this resolution was followed by the adoption of a further resolution which, among other specifications, ordered that the Senate provide notice to the chief justice and request his attendance as presiding officer.[47]

Convening of the Senate as a court of impeachment

_(14576076430)_(1).jpg.webp)

At 1pm on March 5, 1868 (the day after the articles of impeachment were delivered), President Pro-Tempore of the Senate Benjamin Wade gaveled the suspension of legislative business, and the Senate then convened as a court of impeachment with Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presiding, marking the beginning the trial.[24][31][54] Chief Justice Chase was escorted into the chamber by Senators Charles R. Buckalew (D– PA), Samuel C. Pomeroy (R– KY), Henry Wilson (R– MA), who had been appointed the previous day to a committee for the sole purpose of escorting Chase.[49]

On this first day, precursing heavy attendance seen later, the galleries of the Senate were crowded, with it being reported that, "scores of ladies were seated on the steps. The aisles and doors were choked up with spectators".[54] Many members of the House of Representatives crowded on the floors and the lobbies of the Senate chamber, including James Mitchell Ashley (who had been among the earliest and fiercest proponents of impeaching Johnson) and Speaker Colfax.[2][3][54] The Senate's diplomatic gallery was crowded with foreign ministers and senators' wives.[54]

Oaths (March 5 and 6)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Second illustration:Chief Justice Chase administering the juror's oath to Benjamin Wade

On March 5 and 6,[22] the following oath (prescribed in the rules adopted on March 2[49]) was taken both by Chief Justice Chase as the presiding officer of the trial and as a juror's oath by the senators,

I do solemnly swear, that in all things appertaining to the trial of the impeachment of Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, now pending, I will do impartial justice, according to the Constitution and the laws. So help me god.[54]

Once he took his seat at the chair of the Senate at the convening of the trial, Chase declared

Senators, I attend the Senate in obedience to your notice, for the purpose of joining with you in forming a court of impeachment for the trial of the President of the United States, and I am now ready to take the oath.[49]

The oath was then administered to Chief Justice Chase by Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Samuel Nelson.[49][54][55] Chase had opted to take an oath despite the fact that the Senate rules had stated that, as merely a presiding officer, Chase was not required to be sworn any oath.[33] Afterwards, Chase began administering the oath to senators individually in alphabetical order.[49][54]

When Benjamin Wade's turn to take the juror's oath came, Senator Thomas A. Hendricks (D– IN) questioned Benjamin Wade's impartiality and suggested that Wade should be disqualified from sitting as a member of the court due to his conflict of interest.[49][54][56] Hendricks' objection concerned the fact that Wade was, as president pro tempore of the Senate, the first-in-line at the time to succeed Johnson. This meant that, if Johnson was convicted (and thereby removed), Wade would succeed Johnson in occupying the presidency. While the office of president pro-tempore of the Senate was actually third in line under the Presidential Succession Act that governed succession at the time, the vice presidency (the office that was second in line) had been vacant ever since Johnson succeeded to the presidency due to there being no constitutional provision at the time for filling an intra-term vacancy in the vice presidency (such a provision would not exist until nearly a century later after the ratification of Twenty-fifth Amendment).[49][54][56] Several senators stood to respond to Hendricks' objections. Chase first recognized John Sherman (R– OH), who was the other senator representing Wade's state of Ohio. Sherman argued that Ohio was entitled to two representatives in the court of impeachment. When Jacob M. Howard (R– NH) responded to Henricks' objection, he argued that he saw no distinction between the alleged conflict of interest of Wade and the conflict of interest that Senator David T. Patterson (D– TN) had in being an in-law relative of President Johnson.[49][54] Reviled by the Senate's Radical Republican majority, Hendricks withdrew his objection a day later and left the matter to Wade's own conscience.[56][57] Wade ultimately voted for conviction. Wade made promises during the trial to impeachment manager Benjamin Butler that he would appoint Butler as secretary of state if Wade assumed the presidency after a Johnson conviction.[58]

After Hendricks withdrew his objection, Chase administered the oath to Wade and the remaining senators that had not yet taken it.[49][59] After the oaths were administered, Chief Justice Chase submitted a question to the Senate asking whether Senators agreed that the rules for the trial adopted on March 2, 1868 should be considered the rules for the court of impeachment. The Senate voted in the affirmative by voice vote. The Senate next agreed to a motion put forth by Jacob M. Howard to notify the impeachment managers that the Senate was organized as a court of impeachment and ready to receive them. After a pause, at 2:47pm, six of the seven impeachment managers (with Thaddeus Stevens absent) appeared at the bar of the Senate and were announced by the sergeant at arms of the Senate, and were invited by Chief Justice Chase to take their assigned seats at the front of the chamber. After this, the Senate adopted an order put forth by Jacob M. Howard to, as required by the rules and procedures adopted, issue a summons to President Johnson, returnable on March 13 at 1pm.[49]

Delivery of summons to Johnson (March 7)

_(3x4).jpg.webp)

_(3x4).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Second image: Illustration of Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate George T. Brown delivering the Senate's summons to Andrew Johnson at the White House on March 7, 1868

Third image: Chief Justice Chase's writ of summons to Johnson

On March 7, 1868, Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate George T. Brown traveled from the United States Capitol to the White House in order to present Johnson with his summons.[24][60] In addition to the Senate's summons, a writ of summons was sent by Chief Justice Chase to President Johnson on March 7, 1868, notifying him of the pending impeachment trial, giving him both the date of the trial and summarizing the reason he was accused of being, "unmindful[ness] of the high duties of his office".[61]

On the advice of counsel, Johnson opted against appearing at the trial.[24][31][38] Johnson had, at times, personally desired to attend the trial, but was persuaded against doing so by his counsel, who argued that doing so would diminish the presidency.[38] His counsel was concerned that Johnson would lose his temper at the trial if he attended.[62] Johnson did, however, grant a number of interviews with reporters during the course of the trial.[24] Impeachment manager Benjamin Butler had advocated for compelling Johnson's attendance, and felt that the impeachment managers had been "too weak in the knees" in failing to do so.[38][63]

Adoption of rules on admission tickets (March 10)

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

Second image: Illustration of spectators having their tickets checked upon entrance

.jpg.webp)

%252C_from_a_sketch_by_E._Jump._LCCN2011645260_(cropped_to_Gentleman's_gallery).jpg.webp)

The trial was conducted mostly in open session. During the Senate, the Senate chamber galleries were filled to capacity at time, and the great public interest in attendance led to the Senate issuing admission passes for the first time in its history. Rules outlining the distribution of tickets were adopted in a general session of the Senate on March 10. For each day of the trial, 1,000 color coded tickets were printed, granting admittance for a single day.[24][31][47][64] Under there rules, forty of each day's tickets went to the diplomatic corps twenty to the secretary to the president of the United States for use by of the president, four to each senator, four to the chief justice of the Supreme Court, two to each member of the House, two to each associate justice of the Supreme Court, two to the chief and associate justices of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, two to each judge of the Court of Claims, two to each officer of the Cabinet, two to the general commanding the United States Army, and sixty to be issued by the president pro tempore of the senate to reporters of the news media. The remainder of tickets were distributed among the senators in proportion to the number of seats their state held in the House of Representatives.[24][47][65] Members of Congress were inundated with hundreds of requests for the tickets they received.[24] The crowding, combined with hot and humid weather, made the Senate chamber uncomfortable. Attendance waned during the prosecution's presentation, which spectators regarding the prosecution's presentation as boring.[38]

Proceedings on March 13, 23, and 24

.jpg.webp)

The Senate met again as a court of impeachment on March 13, the date given for Johnson to respond to his summons. The Senate chamber was crowded. The Baltimore Sun's report on the proceedings noted a lack of "colored citizens" in attendance.[66] Johnson's defense team asked for 40 days to collect evidence and witnesses since the prosecution had had a longer amount of time to do so, but only 10 days were granted.[66][67]

.jpg.webp)

The Senate met again as a court of impeachment on March 23. During these proceedings, Senator Garrett Davis (D– KY) argued that, because not all states were represented in the Senate (due to Reconstruction), the trial could not be held and that it should therefore be adjourned. The motion was voted down. After the charges against the president were made, Henry Stanbery asked for another 30 days to assemble evidence and summon witnesses, saying that in the 10 days previously granted had only been enough time to prepare the president's reply. House manager John A. Logan argued that the trial should begin immediately and that Stanbery was only trying to stall for time. The request was turned down in a vote 41–12. However, the Senate voted the next day to give the defense six more days to prepare evidence, which was accepted.[67]

Presentations, testimony, arguments, and deliberations

During the trial, forty-one witnesses testified (twenty-five called by the prosecution and sixteen called by the defense),[24] providing live testimony.[68] However, one of the witnesses called by both the defense and prosecution, William G. Moore (secretary to the president[69]), was the same individual, so there were only forty unique witnesses.[70]

Prosecution's presentation (March 30–April 9)

List of witnesses called during the prosecution's presentation (in order first called)[70]

- William J. McDonald (March 31) chief clerk of the Senate[71]

- John W. Jones (March 31) keeper of the Senate stationary[71]

- Charles E. Creecy (March 31 and April 4) appointment cleark in the Treasury Department[71]

- Burt Van Horn (March 31) Republican member of the House of Representatives

- James K. Moorhead (March 31) Democratic member of the House of Representatives

- Walter A. Burleigh (March 31) Republican non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives

- Samuel Wilkeson (April 1) journalist[72]

- George W. Karsener (April 1 and 2)

- Thomas W. Ferry (April 2) Republican member of the House of Representatives

- William H. Emory (April 2) officer of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers

- George W. Wallace (April 2) lieutenant colonel of the United States Army in command of the Garrison of Washington, D.C.[73]

- William E. Chandler (April 2) former First Assistant Secretary of the Treasury

- Charles A. Tinker (April 2 and 3) telegraph operator[71]

- James B. Sheridan (April 3) stenographer[71]

- James O. Clephane (April 3) phonographic reporter[71]

- Francis H. Smith (April 3) official reporter of the House[71]

- William G. Moore (April 3) private secretary to President Johnson[71]

- William N. Hudson (April 3) editor of the Cleveland Leader[71]

- Daniel C. McEwen (April 3) short-hand news reporter[71]

- Everett D. Stark (April 3) reporter[71]

- L. L. Walbridge (April 4) short hand news reporter[71]

- Joseph A. Dare (April 4) short-hand news reporter[71]

- Robert S. Chew (April 4) employee of the United States Department of State[71]

- M.H. Wood (April 9)

- Foster Blodgett (April 9) chair of the Georgia Republican Party Central Committee and former mayor of Augusta, Georgia

The prosecution presented their case between March 30 and April 9.[24] The case that was made mainly focused on Johnson's removal of Stanton. Their case was regarded as boring by spectators, largely laying out already-known facts.[38] While the central focus was Johnson's alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act, other issues were brought up in the prosecution's case.[74] House impeachment managers also characterized Johnson as representing a return of "slave power" to the country.[74] During much of the prosecution's presentation, defense counsel William Evarts would often tie down the proceedings by objecting to Butler's questions, which often resulted in the need for a vote by the Senate on whether to allow the question.[38]

A key argument made by the prosecution was an assertion that Johnson had explicitly violated the Tenure of Office Act by dismissing Stanton without the Senate's consent.[74] Another key argument made the prosecution was an assertion that the president had a duty to faithfully execute laws passed by Congress, regardless of whether the president believes the laws to be constitutional. They argued this was the case because, if a president was not obliged to do so, they could routinely go against the will of Congress (which they argued, in turn, represented the will of the American people, as their elected representatives).[74]

.png.webp)

When the trial commenced on March 30,[74] House manager Benjamin Butler opened for the prosecution with a three-hour speech.[38][30] The speech reviewed historical impeachment trials, dating from King John of England.[38] In this speech, he directly refuted arguments that the Tenure of Office Act was not applicable to Johnson's dismissal of Stanton.[30] In this speech, he also read excerpts of Johnson's speeches from his infamous Swing Around the Circle. These remarks were the basis of the tenth article of impeachment.[30] He also made derisive remarks against Johnson, such as referring to him as an "accidental Chief" and "the elect of an Assassin" in reference to the fact that Johnson was not elected president, but rather, had ascended to the presidency after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.[30] Butler argued that the Senate was presented with the question of whether Johnson, "because of his malversion in office is no longer fit." Butler's speech primarily emphasized the first eight impeachment articles, which focused on Johnson's actions related to Edwin Stanton and Lorenzo Thomas being violations of the Tenure of Office Act, alleging Johnson of claiming for himself a, "most stupendous and unlimited prerogative" to ignore that law through these actions. He conceded that he believed that the last three articles of impeachment (including the tenth, which he had authored) paled in comparison to the "grandeur" of the first articles. To support the legality of the Tenure of Office Act, Butler cited historical precedents, including past laws of Congress and writings by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist Papers. In order to argue that all eleven articles should result in conviction, Butler argued an expansive view on what constituted an impeachable offense, arguing that it included any act that subverted a, "fundamental or essential principle of government, or [was] highly prejudicial to the public interest". Butler received much criticism for remarking in his opening speech that the Senate was "bound by no law, either statute or common," but rather that the senators were, "a law unto yourselfs, bound only by natural principles of equity and justice."[38]

.jpg.webp)

In the case given out over the next several days of presentation, Butler spoke out against Johnson's violations of the Tenure of Office Act and further charged that the president had issued orders directly to Army officers without sending them through General Grant. The prosecution called twenty-five witnesses in the course of the proceedings until April 9, when they rested their case.[24][38] The testimony that was taken during the prosecution's presentation was unexciting. While Stanton could have proven a compelling witness, he was not called due to three points of concern by the impeachment managers. The first concern was a fear if Stanton left his physical office to spend an afternoon testifying before the Senate, Lorenzo Thomas could enter the office and change the locks on him. The second concern was that Stanton could potentially come across as arrogant as a witness. The third concern was that Stanton might prove unable to effectively justify that he deserved to remain in offices against the wishes of Johnson.[38]

The disrespectful character of remarks Butler would make about Johnson during the trial may have hurt the prosecution's case with senators who were on the fence. Butler is argued to have also made a number of strategic errors in his presentation,[30] After their presentation, Butler and his fellow House managers publicly expressed confidence that their presentation was successful. On May 4, Butler spoke before a Republican crowd, and declared, "the removal of the great obstruction is certain." However, privately, they were less optimistic about it.[30]

Defense's presentation (April 9–20)

List of witnesses called during the defense's presentation (in order first called)[70]

- Lorenzo Thomas (April 10) adjutant general of the U.S. Army

- William Tecumseh Sherman (April 11 and 13) major general in the United States Army

- Return J. Meigs III (April 13) clerk of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia[75]

- DeWitt C. Clarke (April 15)

- William G. Moore (April 15) private secretary to President Johnson[76]

- Walter Smith Cox (April 16) attorney

- Richard T. Merrick (April 16) attorney

- Edward O. Perrin (April 16)

- William W. Armstrong (April 17) news reporter[76] and former Ohio secretary of state

- Barton Able (April 17)

- George Knapp (April 17) publisher of The St. Louis Republican[76]

- Henry F. Zeider (April 17) news reporter[76]

- Frederick W. Seward (April 17) United States secretary of state

- Gideon Welles (April 17 and 18) secretary of the navy

- Edgar T. Welles (April 18) son of Gideon Welles[77]

- Alexander Randall (April 18) postmaster general[77]

%252C_from_a_sketch_by_E._Jump._LCCN2011645260_(cropped_to_ladies_gallery)_1.jpg.webp)

The defense's presentation took place between April 9[70] and 20.[24] The defense sought to raise doubt in the minds of senators' minds about Johnson's intent, and sought to question the criminality of the alleged impeachable offenses.[24]

One of the key points argued by the defense was that the language in the Tenure of Office Act was not clear, leaving vagueness as to whether the legislation itself was even applicable to the situation involving Stanton. The defense argued that Johnson had not violated the Tenure of Office Act because President Lincoln did not reappoint Stanton as Secretary of War at the beginning of his second term in 1865 and that he was, therefore, a leftover appointment from his 1861 Cabinet, which, they argued, removed his protection by the Tenure of Office Act.[24][74][38][78]

Another key point argued by the defense was an assertion that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, since, they argued, it interfered with the President's constitutional authority to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed." They argued that a President could not carry out laws when they could not trust their own Cabinet advisors.[74][78] They argued that, even if the act were constitutional, presidents should not be convicted and removed from office for misconstruing their constitutional rights. They argued that if Johnson had misjudged the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, that misjudgment should not result in his removal of office.[24]

Another key argument was that Johnson's intent in firing Stanton had been to test the very constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act before the Supreme Court, which they asserted that he had a right to do.[24]

Another argument made by the defense was that Johnson was only acting, by necessity, to keep a staffed an operational Department of War by appointing Lorenzo Thomas an interim officer. They argued that this had resulted in no public injury that would necessitate Johnson's removal from office.[24]

Another key point argued by the defense was an assertion that presidents should not be removed from office for political misdeeds through impeachment, but, rather, through elections. The defense argued that the Republican Party was abusing impeachment as a political tool.[74]

Defense counsel Benjamin Robbins Curtis called attention to the fact that after the House passed the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate had amended it, meaning that it had to return it to a Senate-House conference committee to resolve the differences. He followed up by quoting the minutes of those meetings, which revealed that while the House members made no notes about the fact that their sole purpose was to keep Stanton in office, and that the Senate had disagreed with that being the intent.[38]

To counter arguments the impeachment managers had made invoking Johnson's public statements as a reason to convict, the defense argued that it was improper to impeach Johnson for exercising his what they asserted was Constitutionally protected free speech, and that any conviction based on the tenth article of impeachment would therefore violate Johnson's constitutional rights.[30]

As their first witness, the defense called Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas. He did not provide adequate information in the defense's cause and Butler made attempts to use his information to the prosecution's advantage.[38] The next witness was General William Tecumseh Sherman, who testified that President Johnson had offered to appoint Sherman to succeed Stanton as secretary of war in order to ensure that the department was effectively administered. This testimony damaged the prosecution, which expected Sherman to testify that Johnson offered to appoint Sherman for the purpose of obstructing the operation or overthrow, of the government. Sherman essentially affirmed that Johnson only wanted him to manage the department and not to execute directions to the military that would be contrary to the will of Congress.[38]

As a witness for the defense, Gideon Welles testified that Johnson's Cabinet had advised the president that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, and both Secretaries William Seward and Edwin Stanton had agreed to create a draft of a veto message. Curtis argued that this was relevant since one of the articles of impeachment charged Johnson with "intending" to violate the Constitution, and Welles testimony portrayed Johnson as having believed that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional. Originally, over the objections of the House Managers, Chief Justice Chase ruled that this testimony was admissible evidence. However, the Senate itself voted to overrule Chase's ruling by a vote of 29–20, thereby deeming it inadmissible as evidence.[79]

During the trial, Chief Justice Chase ruled that Johnson's counsel should be permitted to present evidence that Thomas' appointment to replace Stanton was intended to provide a test case to challenge the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act, including a witness, but the Senate reversed the ruling.[80]

Final arguments (April 22–May 6)

.jpg.webp)

Final arguments took place between April 22 and May 6. The House managers spoke for six days, while the president's counsel spoke for five.[79]

Prosecution's final arguments

The prosecution's closing arguments included charged speech.[79] Thaddeus Stevens painted Johnson as a, "wretched man". John Bingham painted there to be a fundamental need for the, "legislative power of the people to triumph over the usurpations of an apostate President," warning that a failure for this to occur (if the Senate acquitted the president), future historians would regard the impeachment proceedings to have been the moment that, "the fabric of American empire fell and perished from the Earth." Bingham's remarks brought immense applause from the crowd in the Senate gallery.[79]

When one of the managers wanted to examine a witness during the final arguments, the chief justice opined, in response to an objection by a senator, that the Senate would first need to provide an order before such evidence could be allowed to be presented during the final argument. Such an order was thereafter obtained to allow testimony of a witness during the prosecution's final argument.[47]

Defense's final arguments

In his remarks, Groesbeck offered a lively defense of Johnson's perspective of Reconstruction.[79] William Everts argued in his closing argument that violating the Tenure of Office Act did not meet the level of being an impeachable offense.[79]

Closed-door deliberations (May 6–12)

Unlike the rest of the trial, which was conducted in open session before packed galleries, deliberations were held in closed session and their proceedings were kept secret.[24][19] On May 6, Senator George F. Edmunds motioned that the doors be closed, and the Senate voted in the affirmative.[70] The Senate deliberated in closed session on May 6, 7, 11, and 12.[24][70][30]

Delivery of verdict

The Senate was composed of 54 members representing 27 states (10 former Confederate states had not yet been readmitted to representation in the Senate) at the time of the trial. At its conclusion, senators voted on three of the articles of impeachment. On each occasion the vote was 35–19, with 35 senators voting guilty and 19 not guilty. As the constitutional threshold for a conviction in an impeachment trial is a two-thirds majority guilty vote, 36 votes in this instance, Johnson was not convicted.[81] During the votes, senators were called individually and asked by Chief Justice Chase,

Mr. Senator _______, how say you? Is the respondent, Andrew Johnson, president of the United States, guilty or not of a high misdemeanor, as charged in this article of impeachment".[70]

All nine Democratic senators voted against conviction. A total of ten Republican senators defied their party and voted against impeachment.[82] Of the ten Republicans, three were considered "Johnson Republicans", who were certain to vote to acquit. These were James Dixon, James Rood Doolittle, and Daniel Sheldon Norton. However, the other seven, dubbed the "Republican Recusants", had not been initially seen as certain to acquit. These were William P. Fessenden (R– ME), Joseph S. Fowler (R– TN), James W. Grimes (R– IA), John B. Henderson (R– MO), Edmund G. Ross (R– KS), Lyman Trumbull (R– IL), Peter G. Van Winkle (R– WV).[24][38][83] There is substantial evidence that Johnson may have been less in jeopardy of removal than the vote count would indicate and that there were several other Republican senators willing to vote to acquit if their votes had been needed to prevent Johnson's removal,[38] but that there was a deliberate effort by senators to keep the vote close.[84]

Constitutional scholar Charles Black later opined in his seminal work Impeachment: A Handbook that, "the acquittal was almost certainly...on the belief that no impeachable offense had been charged."[85] It was the prevailing view among acquitting senators that the Congress should not remove a president from office due simply to disagreements over policy, style, or administration.[84] Other motivations for some of the Republican Senators' votes to acquit included fears about negative political impact that convicting Johnson could have on the Republican Party and a dislike for President Pro Tempore of the Senate Benjamin Wade, who would have become acting president if Johnson had been removed.[86][87][88]

Per the rules, senators were able to file public statements on the rationale of their votes. Five Republicans that voted to acquit did so. In his statement explaining his votes for acquittal, Republican Lyman Trumbull argued that, while Johnson was unfit for the presidency, it would be wrong to remove him for misconstruing a law that there was reason for doubt about. He argued that convicting him would disrupt the, "harmonious working of the Constitution". He also argued that, had Johnson been convicted, the main source of the American presidency's political power (the freedom for a president to disagree with the Congress without consequences) would have been destroyed, as would Constitution's system of checks and balances.[89] Trumbull stated,

Once set, the example of impeaching a president for what, when the excitement of the hour shall have subsided, will be regarded as insufficient causes, as several of those now alleged against the president were decided to be by the House of Representatives only a few months since, and no future president will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important, particularly if of a political character. Blinded by partisan zeal, with such an example before them, they will not scruple to remove out of the way any obstacle to the accomplishment of their purposes, and what then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution, so carefully devised and so vital to its perpetuity? They are all gone.[89]

In his explanatory statement, filed weeks after the end of the trial, Joseph S. Fowler called the impeachment a, "scheme to usurp my Government." He declared, "I acted for my country, and hove done what I regard as a good act."[38] James Grimes would declare, "I cannot agree to destroy the harmonious working of the Constitution for the sake of getting rid of an Unacceptable President."[24] Peter Van Winkle's explanation dealt with minor details of the language of the articles of impeachment.[38]

There is evidence of efforts by both those supporting the prosecution and the defense having made offers to senators to persuade their votes. This includes evidence of promises of patronage jobs, cash bribes, and political dealmaking being made to solicit votes for acquittal.[38] There is evidence that the prosecution may have attempted to bribe the senators voting for acquittal to switch their votes to conviction. For instance, Maine Senator Fessenden was offered the ministership to Great Britain, and it was found that impeachment manager Butler said, "Tell [Kansas Senator Ross] that if he wants money there is a bushel of it here to be had."[90]

Some possible factors that the acquitting Republican Senators may have taken into account was that Johnson was already in the final year of his presidency, and it appeared certain that he would not be nominated by either major party in the 1868 presidential election. Additionally, Johnson may have given private promises that he would replace Stanton with someone that would be enough to the taste of the members of the Senate that they could pass confirmation.[78]

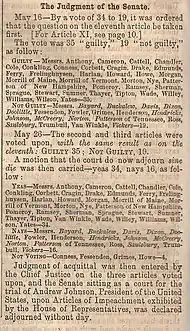

Vote on eleventh article (May 16)

.jpg.webp)

On May 16, the Senate convened to vote on its verdict. A motion was made, and successfully adopted, to vote first on the eleventh article of impeachment. The eleventh article was widely viewed as being the article most likely to result in a vote to convict.[30] For the vote, the Senate galleries were crowded, with the vote being awaited anxiously with great curiosity. The New York Times reported. The spectator galleries of the Senate chamber were crowded. This included its diplomatic box, which the New York Times described as overflowing in a rare occurrence. The members of the House that were present in Washington, D.C. at the time attended the vote. Many individuals crowded elsewhere in the corridors of the Capitol, outside in the grounds of the Capitol, as well as in crowds in the streets of Washington, D.C. eagerly waiting to hear early word of the result in the Senate.[91]

Prior to the vote, Samuel C. Pomeroy, the senior senator from Kansas, told the junior Kansas Senator Ross that if Ross voted for acquittal that Ross would become the subject of an investigation for bribery.[92] Ross was seen as a critical vote, and had been silent about his stance on impeachment throughout the trial and deliberations.[30] Ross' votes against conviction would ultimately be regarded as the decisive vote.[93]

John B. Henderson had, four days prior to the vote, promised to vote for conviction on the eleventh article, but ultimately voted to acquit.[38]

The eleventh article saw a vote of 32–21 to convict, falling one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for a conviction. Afterwards, many newspapers considered the prospect of any other articles producing a conviction to be unlikely since the eleventh article was believed to be the strongest article of impeachment.[94][95][96] News of the vote was greeted with joy by many individuals aligned with Johnson across the nation, with there being public celebrations in several cities, particularly among crowds that had congregated near the bulletin boards of newspaper offices to await word on the verdict.[38][91]

Ten day hiatus

After the vote on the eleventh article resulted in acquittal, in hopes of persuading at least one senator who voted "not guilty" to vote "guilty" on the remaining articles, the Senate voted 32–21 to adjourn for 10 days before continuing voting on the other articles.[38][70]

Believing that they would fail to receive a conviction on any of the other ten articles of impeachment, impeachment managers Thaddeus Stevens and Thomas Williams each wrote up new articles of impeachment that they wanted the House to pass against Johnson, but they failed to receive the approval of the rest of the impeachment managers to pursue this.[38]

During the hiatus the House voted 79–26 on May 16 to approve a resolution introduced by John Bingham that enabled the impeachment managers to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate" and to appoint subcommittees to take testimony.[38][97] A subcommittee was created and began hearing testimony during the hiatus.[38][98] The Butler-led investigation, during the hiatus, began searching for possible corrupt means that may have persuaded senators to acquit. The impeachment managers received a large number of tips from people around the country of leads they should pursue. However, the individual who had Butler's ear the most with his advice on this was news publisher George Wilkes. The investigation included a focus on a number of Johnson-allied figures, including Thurlow Weed (a New York City-based political boss), Samuel Ward (a political lobbyist), and Charles Woolley (a lawyer that was a Johnson ally). The impeachment managers heard from Weed. They sought testimony from Woolley, who kept giving changing excuses for inability to come before them. On the evening of March 25, Sergeant at Arms of the House Nehemiah G. Ordway took custody of Woolley and brought him before the House on March 26. However, Woolley's appearance was interrupted that day by a recess so that congressmen could attend the Senate impeachment trial vote that day.[14][38] The committee turned in a report on their preliminary findings on May 26, hours before the Senate voted.[14] It reported that they had testimony showing implications of bribery, but did not provide solid evidence of bribery.[38]

During the hiatus, many Republicans turned their attention away from the impeachment trial and to the 1868 Republican National Convention being held in Chicago, where Ulysses S. Grant was chosen as the party's nominee for president and Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax was nominated for vice president.[38] By the end of the hiatus, there was little grounds to expect a different result on the remaining articles, as little had changed in the ten days.[38]

Votes on second and third articles and adjournment (May 26)

On May 26, the Senate reconvened the trial. A handful of senators wanted the trial to adjourn until the end of June to allow the impeachment managers to collect more evidence in their investigation into potential corruption before a vote was held. However, since most did not believe the allegations being investigated could be proven, this effort failed.[14] The Senate then voted on the second and third articles, again failing to convict Johnson by the same margin as their votes for the eleventh article, despite the Radical Republican leadership's heavy-handed efforts to change the outcome.[38][99] Article I was not voted on because Republicans were concerned that John Sherman (R– OH) had announced that he would vote to acquit on that count.[38] After both articles failed to result in a conviction invotes to the eleventh article, Senator George Henry Williams (R– OR) motioned to adjourn sine die (meaning without a specific date to resume), which the Senate approved 33–17. Since the Senate never resumed the trial, this ultimately ended the trial without a vote on any further articles.[82][99][100] Before announcing the adjournment by the trial, Chief Justice Chase directed the clerk of the Senate to enter a judgement of acquittal of President Johnson.[19]

Votes on conviction

.jpg.webp)

| Articles of Impeachment, U.S. Senate judgment (36 "guilty" votes necessary for a conviction) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| May 16, 1868 Article XI |

Party | Total votes | |

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 |

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 |

| May 26, 1868 Article II |

Party | Total votes | |

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 |

| Nay (not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 |

| May 26, 1868 Article III |

Party | Total votes | |

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yea (guilty) | 0 | 35 | 35 |

| Nay (Not guilty) |

9 | 10 | 19 |

Vote on adjourning sine die

Aftermath

Political ramifications

Surviving the impeachment effort, Johnson remained in office through the end of his term on March 4, 1869, though largely as a lame duck without influence on public policy.[81]

After the vote to adjourn the trial, Edwin Stanton effectively ended his fight against his dismissal, and instructed his assistant adjunct general to take leadership of the War Department, "subject to the disposal and directions of the president." He had the officer deliver to the White House a letter to Johnson that tendered his resignation (refusing to concede that Johnson had already removed him).[38]

The platform adopted at the 1868 Republican National Convention in May 1868 declared that Johnson had been, "justly impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors, and properly pronounced guilty thereof by the vote of thirty-five senators".[103] None of the Republican senators who voted for acquittal ever again served in an elected office.[104] Although they were under intense pressure to change their votes to conviction during the trial, afterward public opinion rapidly shifted around to their viewpoint. Some senators who voted for conviction, such as John Sherman and even Charles Sumner, later changed their minds.[105][106][107]

As the select committee that wrote them intended, the impeachment trial rules outlined for Johnson's impeachment indeed have been permanent, used in all subsequent federal impeachment trials with very few alterations. The impeachment rules were not altered again after the Johnson trial until the 1935 trial of Harold Louderback saw a single rule change. In the 1970s, the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration looked at possibly again changing the rules in advance of the anticipated impeachment trial that might have followed the impeachment process against Richard Nixon, but after to the resignation of Richard Nixon, this was momentarily abandoned. The rule changes considered in the 1970s were not adopted until the Senate acted upon a further recommendation to adopt them in 1986. No further changes have been made to the rules outlined for the Johnson trial.[25]

Some have argued that the acquittal was an acknowledgement of an understanding that impeachment should be used to address abuses of power and violations of public trust, but not as a means for settling political and policy disputes between the Congress and a president.[78]

The impeachment is regarded as having been part of a greater battle over the balance between the balance of power between the legislative branch (Congress) and the executive branch of the United States federal government.[78] The impeachment and trial of Andrew Johnson had important political implications for the balance between federal legislative branch and executive branch power. It reinforced the principle that Congress should not remove the president from office simply because its members disagreed with him over policy, style, and administration of the office. It also resulted in diminished presidential influence on public policy and overall governing power, fostering a system of governance which future-President Woodrow Wilson referred to in the 1880s as "Congressional Government".[81] The latter dynamic would likely have been heightened had Johnson been convicted in his trial.[108][109]

Scapegoating by Radical Republicans

Some Radical Republicans, looking for a scapegoat to blame for their failure to secure the conviction of Johnson, blamed Chief Justice Chase, accusing him of having swayed the decisions of senators against conviction.[32] Contrarily, he received Democratic praise, with the closing clause of the party platform adopted at the 1868 Democratic National Convention resolving, "that the thanks of the convention are tendered to Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase for the justice, dignity, and impartiality with which he presided over the court of impeachment on the trial of President Andrew Johnson."[110]

Another individual that became a scapegoat for Radical Republicans' failure to secure a conviction was sculptor Vinnie Ream. Senator Ross had been boarding at the home of Ream's family during the trial, and Ream was accused after the trial of having persuaded Ross to vote against conviction.[111] In the aftermath of the trial, Ream was initially ordered to vacate Room A of the United States Capitol, which she had been using as a studio for sculpting her government-commissioned statue of Abraham Lincoln. The House had voted on May 28, 1868 (two days after the trial adjourned) to turn that room into a guard room for the United States Capitol Police.[111][112][113] However, Ream received support from powerful New York sculptors and the assistance her friend Thaddeus Stevens (who had been an impeachment manager) in securing the subsequent passage of a resolution by the House granting her permission to utilize the space as a studio for another year.[111][112]

Impeachment managers investigation into possible corrupt influences

.jpg.webp)

- Individuals depicted in the illustration (left to right) are: John A. Logan, George S. Boutwell, Thomas Williams, James F. Wilson, Thurlow Weed, Benjamin F. Butler, Thaddeus Stevens, John A. Bingham, and Andrew Johnson.

•Impeachment itself is illustrated as an idiomatic "dead horse"

•Boutwell pulls the tail of the horse, saying, "I fear we are getting mired, but I certainly smell corruption."

•Wilson wonders, "Can it be possible that our hobby is decaying already."

•Butler replies, pointing to Thurlow Weed (depicted as a head growing out of a plant in a double-entendre of his last name and the word "weed"), "No its this confounded old Weed called Thurlow that makes the bad smell."

•Stevens remarks, "If we could get another charge into him, he might pull through yet."

•Bingham remarks, "Alas! Seven had proved a fatal number to him." (referring to the seven Republican Senators that received the most blame for voting to acquit).

•Johnson, accompanied by an anthropomorphic-looking ram (a reference to Charles Woolley due to the resemblance of his surname to wool) remarks, "It's no use Gentlemen, your old nag is dead and you can't ride it any more' my Woolley friend finished him."

During the trial's ten day hiatus between votes on the verdicts, the House had voted to allow the impeachment managers to investigate alleged "improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate" and to appoint subcommittees to take testimony.[38][97] A subcommittee was appointed, and already began hearing testimony during the hiatus between Senate verdicts.[38][98] On March 26, 1868, after the trial adjourned, the House voted 91–30 to approve a resolution presented by Benjamin Butler authorizing the House impeachment managers to continue this investigation.[115] Butler led the continuation of the investigation and conducted hearings and inquiry into widespread reports that Republican senators had been bribed to vote for Johnson's acquittal.[38] This effort was quickly dubbed as the "smelling committee" by Democrats and some of the press.[14][38][116]

On March 26, shortly after the Senate trial adjourned, the impeachment managers returned to question Charles Woolley, the Johnson allied lawyer that had been forcefully brought before it by the House's sergeant at arms. After he failed to cooperate with their questioning, refusing to answer questions that he asserted were unrelated to the trial, the House voted 60–51 that day to hold him in contempt of Congress and had him held in custody by the sergeant at arms of the House.[38][115][117] He was first kept in the House Committee on Foreign Affairs' hearing room, but, as his arrest grew in length, he was later moved to the basement room that Vinnie Ream had been utilizing as a sculpture studio, forcing the artist to move her work into the hallway.[38][117] Conservatives charged that Benjamin Butler was intentionally targeting Ream in his successful resolution to turn her studio into a Capitol Police guardroom.[14] Woolley's arrest attracted great media attention.[38][117] After he appeared before the investigative committee and answered their questions to an extent that they found satisfactory, the House voted to discharge Woolley from their custody on June 11, 1868.[19]

In the Butler-led post-trial hearings and investigations there was growing evidence that some acquittal votes were acquired by promises of patronage jobs and cash bribes. Political deals were struck as well. James W. Grimes received assurances that acquittal would not be followed by presidential reprisals; Johnson agreed to enforce the Reconstruction Acts, and to appoint General John Schofield to succeed Stanton. Nonetheless, the investigations never resulted in charges, much less convictions, against anyone.[38] The investigation also boomeranged by uncovering evidence that there had been discussions of bribes for votes to convict. It was discovered during the investigation that Kansas Senator Pomeroy, who voted for conviction, had written a letter to Johnson's postmaster general seeking a $40,000 bribe for Pomeroy's acquittal vote along with three or four others in his caucus.[118]

The investigation, while finding evidence of bribery schemes, failed to definitively prove that bribery had taken place. Butler published his final report of the investigation on July 3, 1868. He hoped the timing of the report's release, a week before the 1868 Democratic National Convention was to be held in New York City, might harm Johnson's chance of receiving his party's nomination.[38] At the convention, the Democrats nominated Horatio Seymour for president and Francis Preston Blair Jr. for vice president.[119]

Later analysis