Second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

The second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States took place on Saturday, March 4, 1865, at the East Portico of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. This was the 20th inauguration and marked the commencement of the second and final term of Abraham Lincoln as president and only term of Andrew Johnson as vice president. Lincoln was assassinated 42 days into this term, and Johnson succeeded to the presidency. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administered the presidential oath of office. This was the first inauguration to feature African Americans in the inaugural parade.[1]

Lincoln taking the oath at his second inauguration. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase administering oath of office. | |

| Date | March 4, 1865 |

|---|---|

| Location | United States Capitol, Washington, D.C. |

| Participants | Abraham Lincoln 16th president of the United States — Assuming office Salmon P. Chase Chief Justice of the United States — Administering oath Andrew Johnson 16th vice president of the United States — Assuming office Hannibal Hamlin 15th vice president of the United States — Administering oath |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal

Political

16th President of the United States

First term

Second term

Presidential elections

Assassination and legacy

|

||

Media coverage

This was the first inauguration to be extensively photographed, and the pictures have since become iconic. One is widely thought to show John Wilkes Booth, who would later assassinate Lincoln.

Walt Whitman, arguably the American poet of the 19th century, reported on the inauguration for the Republican-aligned New York Times.[2]

Inaugural address

While Lincoln did not believe his address was particularly well received at the time, it is now generally considered one of the finest speeches in American history. Historian Mark Noll has deemed it "among the handful of semisacred texts by which Americans conceive their place in the world."[3]

- Fellow–Countrymen:

- At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

- On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

- One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh." If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

- With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.[4]

Vice-presidential oath and inaugural address

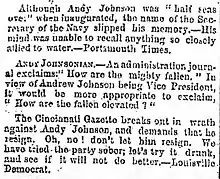

Before the president was sworn in, Vice President-elect Andrew Johnson took his oath of office at the Senate Chamber. At the ceremony Johnson, who had been drinking to offset the pain of typhoid fever (as he explained later), gave a rambling address in the Senate chamber and appeared obviously intoxicated.[5] There is no independent evidence of typhoid but Johnson did most definitely go out drinking the night before the ceremony and then drank several glasses of whiskey in Hannibal Hamlin's office the next morning.[6] In the course of the ceremony Johnson asked to be reminded of the names of various cabinet members and theatrically kissed the Bible on which he was to swear the oath of office.[6] Historian Eric Foner has labeled the inauguration "a disaster for Johnson" and his speech "an unfortunate prelude to Lincoln's memorable second inaugural address." At the time Johnson was ridiculed in the press as a "drunken clown,"[7] and Johnson's performance is remembered as a mortifying fiasco.[6] Lincoln, for his part, "just looked terribly sad."[6]

See also

Further reading

- Burt, John. "Collective Guilt in Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address." American Political Thought 4.3 (2015): 467–88.

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989). ISBN 0-393-31742-0 online edition

- Weiner, Greg. "Of Prudence and Principle: Reflections on Lincoln's Second Inaugural at 150." Society 52.6 (2015): 604–10.

- White, Ronald C. Lincoln's Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural (2006)

References

- "The 20th Presidential Inauguration: Abraham Lincoln, March 04, 1865". United States Senate. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- Dudding, Will (2018-10-22). "When Walt Whitman Reported for The New York Times". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- Noll, Mark (2002). America's God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 426. ISBN 0-19-515111-9.

- "Abraham Lincoln: Second Inaugural Address" Saturday, March 4, 1865. Inaugural Addresses of the Presidents of the United States. Bartleby.com (1989)

- Trefousse p. 198

- Gordon-Reed, Annette (2011). Andrew Johnson (1st ed.). New York, NY: Times Books/Henry Holt. pp. 86–90. ISBN 978-0-8050-6948-8. OCLC 154806758.

- Brinkley, Alan; Dyer (Eds.), David (2004). The American Presidency. New York: Houghton Mifflin. p. 191. ISBN 0-618-38273-9.