Inauguration of Chester A. Arthur

At 2:15 a.m. Eastern Time on September 20, 1881, Chester A. Arthur was inaugurated the 21st president of the United States. The inauguration marked the commencement of Chester A. Arthur's only term (a partial term of 3 years, 165 days) as president. The presidential oath of office was administered by New York Supreme Court Justice John R. Brady at Arthur's private residence in New York City. Two days later, Arthur underwent a second inauguration ceremony in Washington, D.C., with the oath administered by Morrison Waite, the Chief Justice of the United States. Arthur became president following the death of his predecessor James A. Garfield, who had been assassinated by a troubled office seeker, Charles J. Guiteau.

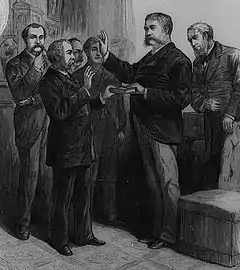

Arthur being administered the oath of office | |

| Date | September 20, 1881 September 22, 1881 |

|---|---|

| Location | 123 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York (September 20) United States Capitol, Washington, D.C. (September 22) |

| Participants | Chester A. Arthur 21st president of the United States — Assuming office John R. Brady Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York — Administering oath (September 20) Morrison Waite Chief Justice of the United States — Administering oath (September 22) |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

20th Vice President of the United States

21st President of the United States

Presidential and Vice presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

Arthur was the fourth vice president to ascend to the presidency after his president's death, but he was the first to do so after a long period of presidential incapacitation. Garfield's long recovery period created an "80-day crisis" during which his cabinet was unsure of how to delegate the responsibilities of the presidency. With Congress in recess and Arthur generally disliked by the public, the cabinet decided not to disperse Garfield's responsibilities. When Garfield succumbed to his wound in September, Arthur assumed his office under the precedent established by John Tyler in 1841. The question of presidential incapacitation remained into the 20th century, particularly after Woodrow Wilson suffered a non-fatal stroke, until the Twenty-fifth Amendment was ratified in 1967.

Background

Presidential succession

The first president of the United States to die in office was William Henry Harrison, who succumbed to pneumonia shortly after midnight on April 4, 1841.[1] At the time, Article Two of the United States Constitution stated that "In the Case of the Removal of the President from Office, or of his Death ... the Same shall devolve on the Vice President".[2] The members of Harrison's cabinet could not agree on the meaning of the article. Some believed that "the Same" meant that the vice president automatically assumed the office of the presidency through the remainder of his predecessor's term, while others interpreted it to mean that the vice president would become an acting or interim president.[3] Under the latter interpretation, then-Vice President John Tyler would only take on the duties of the presidency until a special election decided who would next hold the official title.[4]

Tyler believed that Article Two afforded him both the duties and title of the presidency immediately upon Harrison's death. He argued this interpretation to Harrison's cabinet, who ultimately acquiesced.[5][6] Although Tyler personally believed that the vice-presidential oath of office sufficiently served as his presidential oath, he understood that taking the presidential oath would further legitimize his claim to the office, and a formal inauguration ceremony took place on April 6.[7][8] Three days after the ceremony, he delivered an official presidential address to explain that, as vice president for a deceased president, Tyler "has had devolved upon him the Presidential office".[9] Congress formalized Tyler's assumption of the office with the Wise Resolution that June.[10]

Future presidential inaugurations through Article Two were less controversial than Tyler's. Upon Zachary Taylor's death in office in 1850, his vice president, Millard Fillmore, learned of his predecessor's death by a note from Taylor's cabinet which was addressed to the "President of the United States".[11] Fillmore was formally sworn in on July 10, 1850, in the House of Representatives Chamber of the United States Capitol.[12] Upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the cabinet asked Andrew Johnson where and when he wished to be inaugurated: he chose his hotel room at the earliest possible time.[13] Salmon P. Chase administered the presidential oath of office at the Raleigh Hotel between 10 and 11 a.m. (ET).[14][15]

Election of 1880

By 1880, the Republican Party of the United States was divided into two factions based on their views of the patronage system. The Stalwarts sought to preserve the system, while the Half-Breeds supported James G. Blaine's efforts at civil service reform.[16] At the 1880 Republican National Convention, Blaine was the front-runner for the presidential nomination from the Half-Breed faction, while the Stalwarts sought a third term for Ulysses S. Grant.[17] The two parties remained deadlocked until the 34th ballot, at which point the delegation from Wisconsin united behind James A. Garfield, a young Ohio congressman and Half-Breed who had no interest in running and had instead campaigned on behalf of John Sherman.[16][18] Two ballots later, Garfield won the Republican nomination with 399 votes.[19]

Seeking to appease the Stalwarts, Garfield selected Chester A. Arthur as his running mate. Arthur was viewed as the Stalwarts' second-in-command to New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, and he had previously run the New York Custom House until he was removed from the position by Rutherford B. Hayes for enabling bribery and corruption within the office.[20] Garfield's choice as running mate proved controversial among both factions of the party: the Half-Breeds mistrusted Arthur, who had spurned Conkling and the other Stalwarts by accepting the nomination.[21] Conkling had attempted to persuade Arthur to "contemputously decline" the nomination, arguing that Garfield's loss was a foregone conclusion, to which Arthur replied that even a "barren nomination" would be "a great honor".[22] On the other side of the party, Edwin Lawrence Godkin reassured readers of The Nation that "there is no place in which [Arthur's] powers of mischief will be so small as in the Vice Presidency".[23] Some Republicans asked if it would be possible to split their ballot so that they may vote for Garfield but not Arthur.[23] Garfield defended his running mate against the accusations of corruption, telling Sherman, "he had not been dishonest, just inefficient".[24]

Voter turnout for the 1880 United States presidential election was high, with 78 percent of eligible voters participating.[25] Garfield defeated Winfield Scott Hancock by a 214–155 electoral college vote.[26] He won the popular vote by a margin of only 7,368 votes,[27] at the time the narrowest margin of victory for any United States president-elect,[28] and many of his electoral votes came by narrow margins. Garfield took New York by less than two percent of the vote. If New York's 35 electoral votes had gone to Hancock, he would have won the presidency.[29]

Garfield's assassination

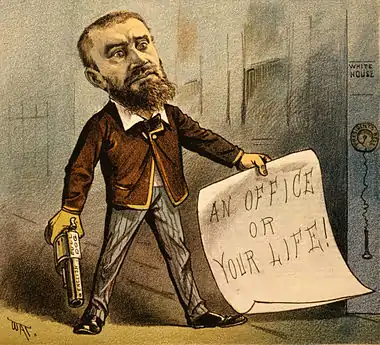

On March 5, 1881, Charles J. Guiteau traveled to Washington, D.C., to petition Garfield for a political office. Guiteau, who is believed to have suffered from either syphilis or schizophrenia that impacted his mental capacities,[30] believed that he was entitled to a diplomatic position for his stump speech in favor of Garfield.[31] He was repeatedly turned away by those through whom he attempted to get an appointment with Garfield, but Arthur took some pity on him, and Guiteau believed that they had a friendship.[32] On May 18, two days after Conkling resigned from his Senate seat, Guiteau decided to assassinate Garfield, believing that God was telling him that "If the President was out of the way every thing would go better".[33] Guiteau purchased a .44 caliber British Bull Dog revolver, a knife, and a box of cartridges on June 6,[34] and he practiced his shooting on the edge of the Potomac River.[35] He spent the following month stalking Garfield, first hoping to shoot him at church before deciding on the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, where Garfield and his wife would board the train to their New Jersey home.[36]

At about 9:30 a.m. ET on the morning of July 2, 1881, Guiteau fired two shots at Garfield, who was accompanied by Blaine at the Baltimore and Potomac station.[37] He was arrested almost immediately after opening fire and told the officers who captured him, "I did it. I will go to jail for it. I am a Stalwart and Arthur will be President."[38] While sitting in the District Jail, Guiteau continued to insist to police that he was personal friends with Arthur, and that he would be rewarded for his assassination of Garfield.[39] New York City Police Commissioner Stephen French feared that the American public would connect Arthur to Guiteau and attempt violence against him. As such, he stationed several police officers and detectives at the Fifth Avenue Hotel where Arthur was staying.[40] Arthur initially avoided traveling to the capital lest he be seen as too eager to assume the presidency, but when Garfield remained alive by 11 p.m., he decided to take a late train into the capital.[41]

The 80-day crisis

Most Americans, including Arthur, believed that Garfield would die quickly after the shooting.[42] Harrison and Taylor were indisposed for a matter of days before succumbing to their respective illnesses, while Lincoln had died only hours after his assassination 16 years prior. Instead, Garfield became the first president to lie incapacitated for an extended period of time, alive but physically and mentally weak.[43] His lingering recovery period complicated the Constitutional crisis begun by Harrison. The most that Article Two had addressed an ill or injured president was in the clause "inability to discharge the powers and duties of his office", which did not entirely apply to Garfield, whose lucidity waxed and waned throughout his recovery process.[44]

Another confounding factor was the general public's dislike of Arthur. Garfield's assassination attempt was met with dread as newspapers and politicians realized that his death would result in Arthur's ascension to the presidency.[45] Animosity towards Arthur rose as Garfield's condition deteriorated and abated when he appeared to head towards recovery.[46] Arthur was additionally loathe to appear too eager to assume the duties of the presidency, lest he be accused of usurpation.[47] He withdrew from public life, afraid of the death threats that he received and of the theory that he was complicit in the president's assassination.[48] Per political scientist Jared Cohen and historian Candice Millard, Arthur had never wanted the presidency, and he saw the vice presidency as his ultimate goal. It came with the prestige of such an elite office but did not require the intense responsibilities that the president faced.[49][50]

Absent any active executive leadership, the United States ran into political and economic upheaval. A Supreme Court vacancy remained unfilled, while the investigation into the Star Route scandal stalled. Foreign affairs broadly required attention, and the stock market, always in some state of flux, demonstrated a downward trend. This lack of federal leadership was exacerbated by the fact that Congress had gone into recess in March and was not called to reconvene until December.[51] Blaine was the first to suggest that Article Two allowed the cabinet to name Arthur acting president while Garfield was incapacitated,[52] an opinion which Arthur himself refused.[53] Garfield's cabinet proposed three courses of action for how to handle the president's long recovery period. Under the first option, they could take advantage of Congress's long recess and allow the incapacitated president to retain his power. Second, they could delegate rather than devolve executive power, through which Garfield would carry out his duties through a selected member of his cabinet. Finally, they proposed that Congress pass an act providing for the "temporary discharge of presidential duties during the president's inability", which would be difficult to do during a recess period.[54] The cabinet ultimately chose not to take any drastic action, taking the chance that nothing of immediate urgency would occur.[55]

Inauguration

Initial swearing-in

Garfield's primary physician, Doctor Willard Bliss, did not believe in the nascent antiseptic procedures promoted by his contemporary Joseph Lister,[56] and Garfield's gunshot wound became infected through Bliss's non-sterile attempts to retrieve the bullet.[57] Two months after he was shot, Garfield died at approximately 10:35 p.m. ET on the evening of September 19, 1881.[58][59] A reporter from The Sun arrived at Arthur's house just after midnight to inform him of Garfield's death. Arthur did not initially believe the report, and he told the reporter, "I hope—my God, I do hope it is a mistake."[60] The initial report was shortly followed by a telegram from United States Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh and signed by four other cabinet members. MacVeigh advised Arthur "to take the oath of office as president of the United States without delay" and asked him to come to Washington "on the earliest train tomorrow".[61] He responded quickly to the telegram, saying, "your intelligence fills me with profound sorrow. Express to Mrs. Garfield my profound sympathy."[62] When a reporter for The New York Times arrived at Arthur's home asking if the new president would make a statement, Aleck Powell turned him away, saying, "He is sitting alone in his room sobbing like a child ... I dare not disturb him".[63]

After collecting himself, Arthur dispatched two carriages to find a suitable judge to administer the oath of office. Elihu Root and Pierre C. Van Wyck returned just before 2 a.m. with New York Supreme Court justice John R. Brady, and fifteen minutes later, Stephen French and Daniel G. Rollins provided the services of Charles D. Donohue. His son Chester Alan Arthur II, meanwhile, was recalled to Arthur's home from his studies at Columbia University.[62] Brady administered the presidential oath at 2:15 a.m. in the front parlor room of Arthur's brownstone at 123 Lexington Avenue, reading off of a scrap of paper on which the oath was handwritten.[62] It was the first inauguration to take place in New York City since the first inauguration of George Washington in 1789.[64] Several reporters gathered outside, while French had posted two police officers outside the property. After reciting the oath, Arthur retired to his library to speak with his friend John Reed, finally going to sleep at 5 a.m.[65]

Arthur had left himself with no immediate successor. His refusal to fill his vacant Senate seat after the March inauguration had prevented the election of a president pro tempore of the Senate, and with Congress in recess, there was no speaker of the House.[62] Arthur, fearing that he would be assassinated en route to Washington, sent a letter to the White House with instructions to hold an immediate special session of the Senate to elect a president pro tempore and advance the line of succession.[62] This letter was unneeded, as Arthur survived the travel, and three weeks later, he presided over the special session in which Thomas F. Bayard was named as president pro tempore of the Senate.[66]

Washington ceremony

Fearing that the hasty initial inauguration, which had been performed by a state official and without any federal record, would cause a legitimacy crisis, Arthur agreed to repeat the presidential oath in a formal ceremony in Washington, D.C.[66] He traveled to Washington on the morning of September 20 to attend Garfield's funeral procession, and the following day, he repeated the oath of office before Chief Justice Morrison Waite.[67] Around 40 individuals were in attendance at the Vice President's Room of the Capitol, including Hayes and Grant, associate justices John Marshall Harlan and Stanley Matthews, several members of Garfield's cabinet, seven senators, and six members of the House of Representatives.[68] Waite further documented the inauguration to keep within the Supreme Court's records.[66]

Unlike the previous vice presidents who had assumed the presidency, Arthur had never before held political office, and politicians and writers did not know what to expect from his inaugural address. In it, he emphasized the strength of presidential succession, saying, "No higher, more assuring proof could exist of our popular government than the fact that though the chosen of the people be struck down, his constitutional successor is peacefully installed without shock or strain."[69] Arthur attempted to quell the public's fears in his inaugural address, promising that he would follow Garfield's vision for the county rather than striking a different path.[70] These promises were well-received by his audience, but Arthur entered the presidency still widely mistrusted and disliked by the general public.[71]

Aftermath

Arthur's presidency was better-received by the public than it had been during Garfield's incapacitation.[72] The motivations behind Garfield's assassination had spurred a national momentum towards civil service reform, and Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act into law on January 16, 1883.[73] The bill formally mandated that federal government positions be given on merit rather than political patronage.[74] During his presidency, Arthur became ill with Bright's disease, which left him with little desire to seek re-election in 1884. While he received several delegates at the Republican convention, Arthur lost the Republican nomination to Blaine, who lost to Grover Cleveland in the 1884 presidential election.[75] Arthur succumbed to the disease on November 18, 1886.[76]

The brownstone in which Arthur took his initial oath of office has undergone several renovations since his presidency.[77] William Randolph Hearst lived in the house after Arthur's death, and in the mid-20th century, it was inhabited by John Clellon Holmes.[78] Since 1944, the building has been occupied by Kalustyan's, a spice shop and deli.[79] The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but in 2016, the government declared the building to have been so transformed not to qualify as a National Historic Landmark.[80]

The question of long-form presidential incapacitation did not end with Garfield. In 1893, Grover Cleveland underwent surgery for oral cancer in secret, with his advisors claiming that he was on vacation to dissuade any rumors about his health.[81] His condition was not revealed to the public until 1917, long after his presidency.[82] In 1919, Woodrow Wilson suffered a nonfatal stroke that left him semi-invalid for the remainder of his term. A number of his confidants conducted his business for him, including his wife Edith.[83] In 1958, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had suffered a number of severe illnesses during his presidency, confided with Vice President Richard Nixon that there should be "specific arrangements" for the Vice President should Eisenhower "incur a disability that precluded proper performance of duty over any period of sufficient length".[83] In 1961, John F. Kennedy and running mate Lyndon B. Johnson agreed to "adhere to procedures identical to those" of Eisenhower and Nixon,[84] and on February 10, 1967, during Johnson's presidential tenure, the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution codified the informal procedure established by Eisenhower, Nixon, Kennedy, and Johnson.[85]

References

- Crapol 2006, p. 8.

- Cohen 2019, p. 7.

- Gerhardt 2013, p. 39.

- Harmon 2019, pp. 46–47.

- Gerhardt 2013, p. 37.

- Cohen 2019, p. 9.

- Harmon 2019, p. 47.

- Crapol 2006, p. 10.

- Crapol 2006, pp. 10–11.

- Cohen 2019, p. 11.

- Cohen 2019, p. 74.

- Finkelman 2011, p. 72.

- Trefousse 1989, p. 194.

- Harmon 2019, p. 87.

- Cohen 2019, p. 116.

- Cohen 2019, p. 140.

- Millard 2011, p. 34.

- Millard 2011, pp. 39–49.

- Millard 2011, pp. 50–51.

- Clark 1993, pp. 23–24.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 142–145.

- Harmon 2019, p. 100.

- Clark 1993, p. 27.

- Clark 1993, pp. 26–27.

- Millard 2011, p. 72.

- Ackerman 2003, pp. 220–221.

- Peskin 1978, p. 510.

- Cohen 2019, p. 146.

- Ackerman 2003, p. 221.

- Resnick 2015.

- Ackerman 2003, p. 265.

- Cohen 2019, p. 155.

- Millard 2011, p. 110.

- Clark 1993, p. 49.

- Millard 2011, p. 117.

- Millard 2011, pp. 138–141.

- Cohen 2019, p. 157.

- Ackerman 2003, p. 379.

- Millard 2011, p. 159.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 160–161.

- Greenberger 2017, pp. 158–159.

- Greenberger 2017, pp. 158–160.

- Millard 2011, pp. 253–254.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 167–168.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 161.

- Cohen 2019, p. 166.

- Cohen 2019, p. 168.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 162.

- Cohen 2019, p. 160.

- Millard 2011, p. 193.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 166–167.

- Peskin 1978, p. 604.

- Ackerman 2003, p. 421.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 168–169.

- Cohen 2019, p. 169.

- Millard 2011, p. 185.

- Millard 2011, pp. 268–269.

- Millard 2011, p. 265.

- Harmon 2019, p. 101.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 169–170.

- Clark 1993, p. 109.

- Cohen 2019, p. 171.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 172.

- Hendricks 2015, p. 173.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 173.

- Cohen 2019, p. 172.

- Greenberger 2017, pp. 174–15.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 175.

- Harmon 2019, p. 102.

- Millard 2011, p. 269.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 176.

- Cohen 2019, p. 173.

- Greenberger 2017, pp. 183, 207.

- Millard 2011, p. 289.

- Cohen 2019, pp. 181–182.

- Greenberger 2017, p. 236.

- National Park Service.

- Besonen 2015.

- Roberts 2014.

- Roberts 2019, p. 101.

- Schlup 1979, pp. 304–306.

- Schlup 1979, p. 304.

- Stathis 1982, p. 209.

- Stathis 1982, p. 210.

- Stathis 1982, p. 211.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield. New York, NY: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1151-5.

- Besonen, Julie (December 11, 2015). "Holographic Studios and Kalustyan's Cafe in Kips Bay". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- Clark, James C. (1993). The Murder of James A. Garfield: The President's Last Days and the Trial and Execution of His Assassin. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-89950-910-X.

- Cohen, Jared (2019). Accidental Presidents: Eight Men Who Changed America. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-5011-0984-3.

- Crapol, Edward P. (2006). John Tyler: The Accidental President. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-7223-9.

- Finkelman, Paul (2011). Millard Fillmore: The American Presidents Series, The 13th President, 1850–1853. New York, NY: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-8715-4.

- Gerhardt, Michael J. (2013). The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-996779-7.

- Greenberger, Scott S. (2017). The Unexpected President: The Life and Times of Chester A. Arthur. New York, NY: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82390-9.

- Harmon, F. Martin (2019). Presidents by Fate: Nine Who Ascended through Death or Resignation. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4766-3684-9.

- Hendricks, Nancy (2015). America's First Ladies: A Historical Encyclopedia and Primary Document Collection of the Remarkable Women of the White House. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. ISBN 978-1-61069-883-2.

- Millard, Candice (2011). Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine and the Murder of a President. New York, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-52626-5.

- National Park Service. "Chester A. Arthur House". United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- Peskin, Allan (1978). Garfield: A Biography. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-873-38210-6.

- Resnick, Brian (October 4, 2015). "This Is the Brain that Shot President James Garfield". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- Roberts, Sam (December 8, 2014). "Where a President Took the Oath, Indifference May Become Official". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- Roberts, Sam (2019). A History of New York in 27 Buildings: The 400-Year Untold Story of an American Metropolis. New York, NY: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-62040-980-0.

- Schlup, Leonard (1979). "Presidential Disability: The Case of Cleveland and Stevenson". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 9 (3): 303–310. JSTOR 27547485.

- Stathis, Stephen W. (1982). "Presidential Disability Agreements Prior to the 25th Amendment". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 12 (2): 208–215. JSTOR 27547806.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography. New York, NY and London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31742-0.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)