Anton Meyer

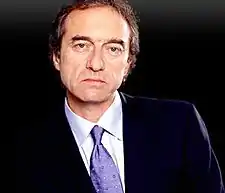

Anton Meyer is a fictional character from the BBC medical drama Holby City, played by actor George Irving. He appeared in the series from its first episode, broadcast on 12 January 1999, until series four, episode 46, broadcast on 20 August 2002. His role in the show is that of consultant cardiothoracic surgeon and head of the cardiothoracic surgery department at Holby General. Irving had considerable input in creating the character, who was initially envisioned by the series producers as an Iranian surgeon named Hussein. At Irving's suggestion, Meyer became Hungarian, an emigrant to Britain following the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Little of the backstory created for Meyer was ever revealed on-screen, as part of a deliberate bid to present the character as enigmatic, allowing viewers to project their own imagination onto him.

| Anton Meyer | |

|---|---|

| Holby City character | |

| |

| First appearance | "Whose Heart Is It Anyway?" 12 January 1999 |

| Last appearance | "Pawns in the Game – Part One" 20 August 2002 |

| Created by | Tony McHale Mal Young |

| Portrayed by | George Irving |

| Spinoff(s) | Casualty, 2002 |

| In-universe information | |

| Occupation | Consultant cardiothoracic surgeon Clinical Chairman Head of cardiothoracic surgery |

| Family | Hannah Philips (sister) |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

Meyer is a driven, arrogant surgeon, with high expectations of his colleagues. His major storylines see him operate on his own sister, fear that he may have motor neuron disease, lose his spleen after being shot in a road rage incident, and ultimately depart from Holby for Michigan when the hospital Board make impositions on his autonomy. Irving made the decision to leave the series as he struggled to set the character aside outside of work, which had a negative impact on his personal life. He ruled out the possibility of returning to Holby City in future, preferring his memory of Meyer to remain untarnished.

Meyer proved popular with viewers and critics. Jim Shelley of The Mirror described Meyer as "one of the best characters on television in recent years".[1]

Storylines

Meyer's major storylines include operating on his own sister when she falls ill, despite a long-term enmity with his brother-in-law, Greg.[2] He seeks help from his friend, neurologist Professor Charles Merrick (Simon Williams), when he fears he may have motor neuron disease, but Merrick deduces he has an easily treatable thyroid problem instead.[3] Merrick's daughter Victoria (Lisa Faulkner) works on Meyer's firm for a period as a Senior house officer (SHO). When she is murdered by the irate father of one of her patients, Meyer becomes involved when he is trapped in a lift with her killer, James Campbell. Campbell overdoses on pills and dies in the lift before Meyer can revive him to face justice.[4]

At the beginning of series four, Meyer is shot in a road-rage incident on his way to work. This sees the introduction of Ric Griffin (Hugh Quarshie) who performs lifesaving surgery to remove the bullet from Meyer's spine. The culprit is later admitted to the hospital as a patient, when he crashes his car after trying to flee following the shooting. He tries to escape from the hospital in fear that the police will discover him, and after three attempts at leaving the hospital, he finally achieves his goal but collapses in the hospital car park and dies.[5]

When the parents of Rufus Wooding, a young patient of Meyer's, suddenly withdraw their consent for a complicated operation, total cavo-pulmonary connection (TCPC), Meyer discovers that his SHO, Sam Kennedy (Collette Brown), has intervened and persuaded the parents not to go ahead with surgery.[6] Believing that his authority has been undermined, Meyer promptly fires her.[7] Kennedy threatens to go to the press if Meyer is not investigated, so the hospital Board begin an enquiry, during which Meyer is suspended. The investigation is headed by Meyer's old friend and rival, Tom Campbell-Gore (Denis Lawson).[8] It concluded that Meyer's clinical skills were exemplary and unquestionable, although the Board, aware that Meyer's penchant for taking extremely difficult cases has made hospital death rates appear bad, remove Meyer's discretion to decide when to operate in such cases. This decision angers Meyer, who argues that he performs operations that are in the interests of the patients not league tables. The Board also relieve Meyer of his registrar Alex Adams (Jeremy Sheffield). Meyer resigns to work in Michigan to develop an artificial heart, while Campbell-Gore takes his post at Holby.[9]

Creation

Irving was heavily involved in the creation of his character, writing Meyer's biography before assuming the role. He felt that it was important for him to understand Meyer's motivation and the reason he is so driven, as the character is presented as a "peacock ogre" who throws scalpels at one of his colleagues in an early episode, and unless Irving could fathom why, his portrayal would be "one step removed".[10] Meyer was loosely based on the cardiothoracic surgeon Sir Magdi Yacoub. He was originally intended to be of Iranian descent and had the surname Hussein, before the series producers changed their minds and made him central European instead. Irving had developed a Hungarian accent for a film role prior to his involvement with Holby City, and decided that "Meyer was temperamentally Hungarian–gloomy with a bit of Mediterranean liveliness."[10] It was decided that Meyer had left Hungary following the 1956 uprising, with his parents, who were intellectuals.[10]

Although it was decided he has a sister, a wife and a daughter, Meyer's personal life is rarely mentioned on screen, enabling viewers to perceive him as a strong man onto whom they can "project whatever they want from their own imagination." Irving believes that modern television drama is populated by characters prone to disclosing everything about themselves, and so feels that having an enigmatic character like Meyer, who behaves in the reserved vein of Humphrey Bogart and Spencer Tracy, makes for a "refreshing change".[10] He commented that revealing more of Meyer's personal life would be anticlimactic compared to viewers' expectations.[10] As preparation for the role, Irving observed coronary artery bypass surgery performed at Papworth and Middlesex Hospital,[10] deeming the experience an "enormous privilege".[11] He had a "real fascination" with medicine and the human body prior to assuming the role, and considered studying biology at university.[12]

Development

Irving concentrated on his own ideas of Meyer's characterisation when playing him, believing it was important to ignore outside input, as Meyer in turn is unperturbed by others' opinions of him. Irving describes Meyer as a driven man, determined to only work with colleagues who meet his exacting standards. He feels that Meyer's "dry sense of humour" and bullying manner are both tools he uses to ensure colleagues meet his standards.[13] Irving believes that Meyer's manipulative nature actually serves the greater good of the hospital, and despite his perfectionist and purist tendencies, Meyer is actually a great humanist, who holds his staff in the highest regard.[14]

Graham Keal of the Birmingham Post observed that Meyer begins the series as a "hate figure"–ferocious, unbending and unsmiling, but is actually more complex a character than that, with "much to admire too."[11] Shane Donaghey of The People compared Meyer to Hannibal Lecter, describing him as "Part panto villain, part grim reaper, with a bedside manner of a cruel vet" and commenting that he manages his department "with an iron fist veiled in a concrete glove."[15]

Meyer has a penchant for listening to classical music whilst in theatre, and has a "right-hand-man" in his registrar, Nick Jordan (Michael French).[11] Meyer's catchphrase is "Walk with me",[12] an instruction he issues to his staff while, according to The Mirror's Jim Shelley, "sneer[ing] imperiously" and "saunter[ing] around the wards like a Roman emperor, suavely saving lives and damning other doctors with their own inadequacies."[1]

Irving was dismayed by the storyline which saw Meyer shot in a road rage incident, describing filming the scenes as an "unpleasant experiences", the worst aspect being that Meyer loses his spleen as a result of his injuries.[16] Of the later storyline which sees Meyer investigated by Tom Campbell-Gore on behalf of the hospital Board, Denis Lawson explained: "[Campbell-Gore] actually rather fancies Meyer's job but if he finds against him in the investigation he cannot get the job because it's a conflict of interest. So he has to play a rather clever game, which he does." On taking over as head of the cardiothoracic surgery department, he commented: "George is fantastic in the show, but obviously I'm going to do something very, very different, so I don't feel that I'm stepping into his shoes."[17]

After four years in the role, Irving decided to leave Holby City and return to performing in theatre. Of his decision to leave, Irving explained that, while he enjoyed Meyer's sureness and confidence, he found it difficult to "switch off" the character outside of work, and had been forced to "put the rest of his life on hold" whilst part of the series, deeming it to be an "intense experience."[12] He felt that, had he stayed in the series, Meyer could not have remained enigmatic much longer, and believed: "you have to stop when a character's time is through."[18] Following Irving's departure from Holby City, Benji Wilson of the Radio Times questioned whether he would ever consider returning. Irving responded: "I don't know—my feeling is that Meyer was of his time. He's the kind of character that belongs at the launch of series like Holby and I think that's where he should remain. The memory of Meyer is important to me and I want it to stay as it is."[19]

Reception

The broadcast of the first episode brought positive comments for Irving and Meyer from television critics. In the Birmingham Post, Graham Keal called Irving's portrayal "a charismatic combination of autocratic arrogance and dry wit", and noted that the character's interactions with Nick Jordan "form the programme's primary double act".[11] Andrew Billen in the New Statesman called Meyer the most compelling character of the series,[20] while Kathleen Morgan of the Daily Record similarly deemed Meyer the star of the show, writing that Irving: "gave a chilling performance as a man who saves lives simply to boost his ego."[21] Following the broadcast of the second episode, Daily Mirror critic Charlie Catchpole wrote that Irving gave the best performance in a hospital drama as "a rude, eccentric, conceited, arrogant bully" since Tom Baker in Medics.[22]

John Russell of The People disliked the storyline which saw Meyer operate on his own sister, describing it as "something between a carve up and a cock up", and commenting that he was "so disturbed" he "switched the tripe off",[23] however, fellow People critic Shane Donaghey lauded Meyer as the only reason to watch Holby City.[15] Tony Purnell of The Mirror gave a poor review when Meyer did not appear for several episodes, commenting that the show was in "very poor health" in his absence, and "the sooner he returns, the better."[24] Purnell praised Meyer's return two episodes later, however was concerned by his Motor Neurone Disease scare, deeming Meyer "the lifeblood of the series" and writing that Holby City could "ill afford to lose him".[25]

Jim Shelley of The Mirror similarly hoped for Meyer to "get well soon and resuscitate the series."[26] Shelley selected the character as a runner-up for his 2001 "Man of the Year" award,[27] and upon the character's exit from Holby City, described him as "a study in arrogance and laconic authority [...] one of the best characters on television in recent years."[1]

Meyer has been particularly well received by female Holby City fans, elevating Irving to sex-symbol status.[28] Irving felt that this was "fairly predictable in terms of the nature of Meyer—tough and masterful—combined with the aphrodisiac of power, and the life and death aspects of his job."[10] He commented that he was surprised by the positive reaction to his character, explaining: "He seems to have captured people's imaginations, but it's difficult to put your finger on what he has. I think it's got something to do with being a character who says exactly what he means all the time. He's got integrity, which I admire anyway, and I expect the audience responds to that. Surgeons seem to like him too. I find that particularly gratifying. He's got the courage to do what's right for his work and his patients and not worry about popularity or being liked."[28] Conversely, Irving noted that after assuming the role, members of the public would sometimes "give a kind of shudder" upon encountering him, associating him with his character.[29]

References

- Shelley, Jim (21 August 2002). "Ant was a cut above the rest". The Mirror. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- Sam Wheats (writer), Julie Edwards (director) (7 January 2000). "Chasing the Dragon". Holby City. Series 2. Episode 7. BBC. BBC One.

- Andrew Rattenbury (writer), Adrian Bean (director) (29 December 2000). "A Christmas Carol: Part 2". Holby City. Series 3. Episode 9. BBC. BBC One.

- Andrew Rattenbury (writer), Paul Wroblewski (director) (5 June 2001). "The Road Less Travelled". Holby City. Series 3. Episode 30. BBC. BBC One.

- Al Hunter Ashton (writer), Nigel Douglas (director) (9 October 2001). "Rogue Males". Holby City. Series 4. Episode 1. BBC. BBC One.

- Stuart Morris (writer), James Strong (director) (1 August 2002). "Judas Kiss: Part 1". Holby City. Series 4. Episode 43. BBC. BBC One.

- Stuart Morris (writer), James Strong (director) (6 August 2002). "Judas Kiss: Part 2". Holby City. Series 4. Episode 44. BBC. BBC One.

- Martin Jameson (writer), Keith Boak (director) (13 August 2002). "New Hearts, Old Scores". Holby City. Series 4. Episode 45. BBC. BBC One.

- Julia Weston (writer), Keith Boak (director) (20 August 2002). "Pawns in the Game". Holby City. Series 4. Episode 46. BBC. BBC One.

- Duncan, Andrew (2 October 2001), "I'm capable of all Meyer is, but I don't have his certainty", Radio Times

- Keal, Graham (8 January 1999). "Drama gets right to the heart of the matter". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Slade, Alison (20 August 2002), "Walk With Me", TVTimes

- McMullen, Marion (19 January 1999). "Tonight's Highlights". Coventry Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "George gets to heart of the matter". Liverpool Echo. 9 October 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Donaghey, Shane (11 August 2002). "Telly: Mey-er hero". The People. Retrieved 2 October 2023.

- Robins, Derek (1 October 2001), "George Irving on Holby City", Teletext

- Ford, Rory (17 August 2002). "In The Doc". Edinburgh Evening News. Johnston Press. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- Wright, Wes (11 May 2007), "Octagon tonic for a Holby city star", The Bolton News, Newsquest

- Wilson, Benji (14 March 2006), "Radio Times - One Final Question", Radio Times

- Billen, Andrew (29 January 1999). "Weak medicine". New Statesman. p. 41. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- Morgan, Kathleen (13 January 1999). "Last Night; Spin off is a real tonic for fans of doc dramas". Daily Record. Glasgow, Scotland. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Catchpole, Charlie (19 January 1999). "Charlie Catchpole: TV column". The Mirror. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Russell, John (9 January 2000). "Hot Telly: What's Rot". The People. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Purnell, Tony (1 December 2000). "Last Night's View: Sopranos hit perfect note". The Mirror. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Purnell, Tony (15 December 2000). "Last Night's View: Surgeon loses a cutting edge". The Mirror. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- Shelley, Jim (23 October 2001). "Shelley Vision: Comment". The Mirror. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Shelley, Jim (1 January 2002). "Shelley Vision: The Shaftas 2001: And Jim Shelley Can Really Dish It Out". The Mirror. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- McMullen, Marion (8 December 2001). "Weekend TV: Women want Meyer of George!". Coventry Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- McMullen, Marion (23 September 2000). "Carry on doctors". Coventry Telegraph. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

External links

- Anton Meyer at BBC Online

- Anton Meyer on IMDb