Antonov An-124 Ruslan

The Antonov An-124 Ruslan (Russian: Антонов Ан-124 Руслан; Ukrainian: Ан-124 Руслан, lit. 'Ruslan'; NATO reporting name: Condor) is a large, strategic airlift, four-engined aircraft that was designed in the 1980s by the Antonov design bureau in the Ukrainian SSR, then part of the Soviet Union (USSR). The An-124 is the world's second heaviest gross weight production cargo airplane and heaviest operating cargo aircraft, behind the destroyed one-off Antonov An-225 Mriya (a greatly enlarged design based on the An-124) and the Boeing 747-8.[4] The An-124 remains the largest military transport aircraft in service.[5]

| An-124 Ruslan | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Antonov An-124 Ruslan preparing to land | |

| Role | Heavy transport aircraft |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Design group | Antonov |

| Built by | Antonov Serial Production Plant Aviastar-SP |

| First flight | 24 December 1982[1] |

| Introduction | 1986 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Aerospace Forces Volga-Dnepr Airlines Antonov Airlines |

| Produced | 1982–2004 |

| Number built | 55[2] |

| Developed into | Antonov An-225 |

In 1971, design work commenced on the project, which was initially referred to as Izdeliye 400 (Product #400), at the Antonov Design Bureau in response to a shortage in heavy airlift capability within the Military Transport Aviation Command (Komandovaniye voyenno-transportnoy aviatsii or VTA) arm of the Soviet Air Forces. Two separate final assembly lines plants setup for the aircraft, one at Aviastar-SP (ex. Ulyanovsk Aviation Industrial Complex) in Ulyanovsk, Russia and the other was the Kyiv Aviation Plant AVIANT, in Ukraine. Assembly of the first aircraft begun in 1979; the An-124 (which was sometimes referred to as the An-40 in the West) performed its maiden flight on 24 December 1982. The type made its first appearance in the Western world at the 1985 Paris Air Show. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, commercial operations were quickly pursued for the An-124, leading to civil certification being obtained by Antonov on 30 December 1992. Various commercial operators opted to purchase the type, often acquiring refurbished ex-military airlifters or stored fuselages rather than new-build aircraft.

By July 2013, 26 An-124s were reportedly in commercial service while a further ten airlifters were on order.[6] During 2008, it was announced that Russia and Ukraine were to jointly resume production of the type. At one point, it looked as if Russia would order 20 new-build airlifters. However, in August 2014, it was reported that the planned resumption of manufacturing had been shelved due to the ongoing political tensions between Russia and Ukraine.[7] The sole remaining production facility is Russia's Aviastar-SP in Ulyanovsk. The various operators of the An-124 are in discussions with respect to the continuing airworthiness certification of the individual An-124 planes. The original designer of the An-124 is responsible for managing the certification process for its own products, but the Russia-Ukraine conflicts are making this process difficult to manage. In 2019, there were 26 An-124s in commercial service.

Development

Background

During the 1970s, the Military Transport Aviation Command (Komandovaniye voyenno-transportnoy aviatsii or VTA) arm of the Soviet Air Forces had a shortfall in strategic heavy airlift capacity. Its largest aircraft consisted of about 50 Antonov An-22 turboprops, which were used heavily for tactical roles. A declassified 1975 CIA analysis concluded that the USSR did "...not match the US in ability to provide long-range heavy lift support."[8] Soviet officials sought not only additional airlifters, a substantial increase in payload capacity was also desirable so that the same task could be completed with fewer trips.[9]

In 1971, design work on the project commenced at the Antonov Design Bureau; the lead designer of the An-124 (and the enlarged An-225 derivative) was Viktor Tolmachev.[10][11] During development, it was known as Izdeliye 400 (Product #400) in house, and An-40 in the West. The design produced broadly resembled the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, an American strategic airlifter, but also incorporated numerous improvements, the greater use of carbon-fibre composites in its construction (comprising around 5% of the aircraft's total weight) and the more extensive use of titanium being amongst these benefits. Aluminium alloys make up the primary material used in its construction, limited use of steel and titanium alloys were also made.[9] Unlike the C-5, it lacks a fully-pressurised cargo bay or the ability to receive fuel in-flight.[12]

In 1973, the construction of the necessary facilities to produce the new airlifter began. Two separate final assembly lines plants were established to produce the airlifter: the company Aviastar-SP (ex. Ulyanovsk Aviation Industrial Complex) in Ulyanovsk, Russia and by the Kyiv Aviation Plant AVIANT, in Ukraine. Furthermore, the programme used components, systems, and various other elements drawn from in excess of 100 factories across the Eastern world. In 1979, manufacturing activity on the first airframe began.[13]

On 24 December 1982, the type performed its maiden flight. Three years later, the An-124 made its first appearance in the Western world when an example was displayed at the 1985 Paris Air Show.[9] Following the fall of the Soviet Union, commercial operations of the An-124 became an increasingly important area of activity; to this end, civil certification was sought for the type by Antonov; this was issued on 30 December 1992.[14]

Post-Soviet developments

Sales of the An-124 to various commercial operators proceeded throughout the 1990s and into the mid 2000s; many of these were former military aircraft that were refurbished by Antonov prior to delivery, or unfinished fuselages that had been preserved, rather than producing new-build aircraft.[15] During the early 2000s, the cargo operator Volga-Dnepr opted to upgrade its An-124 freighter fleet, these works included engine modifications to conform with chapter four noise regulations, various structural improvements that increased service life, and numerous avionics and systems changes to facilitate four person operations, reducing the crew needed from six or seven.[16]

During April 2008, it was announced that Russia and Ukraine had agreed to resume the production of the An-124 in the third quarter of 2008.[17] One month later, a new variant — the An-124-150 — was announced; it featured several improvements, including a maximum lift capacity of 150 tonnes.[18] However, in May 2009, Antonov's partner, the Russian United Aircraft Corporation announced it did not plan to produce any An-124s in the period 2009–2012.[19] During late 2009, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev ordered production of the aircraft resumed; at this point, Russia was expected to procure 20 new-build An-124s.[20][21] In August 2014, Jane's reported that, Russian Deputy Minister of Industry and Trade Yuri Slusar announced that production of the An-124 had been stopped as a consequence of the ongoing political tensions between Russia and Ukraine.[7]

In late 2017, multiple An-124s were upgraded by the Aviastar-SP plant in Ulyanovsk, Russia, three of which were reportedly scheduled to return to flight during the following year. As Russia–Ukraine relations continued to sour, Antonov begun to source new suppliers while also pushing to westernize the An-124.[16] During 2018, the American engine manufacturer GE Aviation was studying reengining it with CF6s for CargoLogicAir, a Volga-Dnepr subsidiary. It was believed that this would likely provide a range increase; as Volga-Dnepr Group operated 12 aircraft, the change would imply purchasing between 50 and 60 engines with spares.[16] The Russian engine specialist Aviadvigatel also indicated that a further development of its PD-14, which was intended for use on an upgraded model of the Russian-manufactured An-124, designated PD-35, generated 50% more power than the present Ukrainian Progress D-18T engines.

During January 2019, Antonov revealed its plans to restart production of the An-124 without support from Russia.[22]

Russian replacement design

At MAKS Air Show in 2017, the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI) announced its An-124-102 Slon (Elephant) design to replace the similar An-124-100. The design was detailed in January 2019 before wind tunnel testing scheduled for August–September. It is intended to be produced at the Aviastar-SP factory in Ulyanovsk. It should transport 150 t (330,000 lb) over 3,800 nmi (7,000 km) (up from 1,675 nmi, 3,102 km), or 180 t (400,000 lb) over 2,650 nmi (4,910 km) at 460 kn (850 km/h). The Russian MoD wants a range of 4,100 nmi (7,600 km) with five Sprut-SDM-1 light tanks, their 100 crew and 300 armed soldiers.[23]

The planned An-124-102 is larger at 82.3 m (270 ft) long from 69 m (227 ft), with a 87–88 m (286–290 ft) span versus 73.3 m (240.5 ft) and 24.0 m (78.7 ft) high compared with 21.0 m (68.9 ft).[24] A new higher aspect ratio, composite wing and a 214–222 t (472,000–489,000 lb) airframe would allow a 490–500 t (1,080,000–1,100,000 lb) gross weight. It should be powered by Russian PD-35s developed for the CR929 widebody, producing 35 tf (77,000 lbf) up from 23 tf (51,000 lbf). Two fuselages are planned, one for Volga-Dnepr with a width of 5.3 m (17.4 ft) from the An-124's 4.4 m (14.4 ft), and one for the Russian MoD of 6.4 m (21 ft) wide to carry vehicles in two lines.[23]

On 5 November 2019, the TsAGI released pictures of a 1.63 m (5 ft 4 in) long and 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) wide model, ahead of windtunnel testing.[25][26][27] On 26 March 2020, TsAGI released new pictures of a wind tunnel model, announcing that the researchers of the Institute had completed the first cycle of aerodynamic testing; the results confirmed the characteristics laid down during preliminary studies.[28]

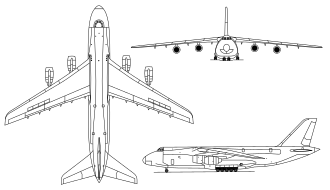

Design

The Antonov An-124 Ruslan is a large, strategic airlift, four-engined aircraft. Externally, it bears numerous similarities to the American Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, having a double fuselage to allow for a rear cargo door (on the lower fuselage) that can open in flight without affecting structural integrity.[29][12] The An-124 has a slightly shorter fuselage, has a slightly greater wingspan, and is capable of carrying a 17 percent larger payload. In place of the C-5's T-tail, the An-124 is furnished with a conventional empennage, similar in design to that of the Boeing 747. Many of the flight control surfaces, such as the slats, flaps, and spoilers, closely resemble or are identical to those of the C-5. The An-124 features a fly-by-wire control system.[30] This is a hybrid control system, as it also implements conventional mechanical controls for some aspects; these have been arranged in a manner that provides redundancy against the failure of a single hydraulic circuit.[9]

A single An-124 is capable of carrying up to 150 tonnes (150 long tons; 170 short tons) of cargo internally in a standard military configuration; it can also carry 88 passengers in an upper deck behind the wing centre section. The forward area of this upper deck is where the flight deck and the crew area accommodated; movement between the upper and lower decks is via a pair of foldable internal ladders.[9] The cargo compartment of the An-124 is 36×6.4×4.4 m (118×21×14 ft), ca. 20% larger than the main cargo compartment of the C-5 Galaxy, which is 36.91×5.79×4.09 m (121.1×19.0×13.4 ft). Largely due to the limited pressurisation of its main cargo compartment (24.6 kPa, 3.57 psi),[31][30] the airlifter has seldom been used to deploy paratroopers or to carry passengers, as they would typically require oxygen masks and cold-weather clothing in such conditions.[32] In comparison, the upper deck is fully pressurised.[9] The floor of the cargo deck is entirely composed of titanium, a measure that is usually prohibited by the material cost.[30] It is suitable for carrying almost any heavy vehicle, including multiple main battle tanks.[9]

The An-124 is powered by four Lotarev D-18 turbofan engines, each capable of generating up to 238–250 kN of thrust. To reduce the landing distance required, thrust reversers are present.[9] Pilots have stated that the airlifter is relatively light on the controls and is easy to handle for an aircraft of its size.[33] A pair of TA18-200-124 auxiliary power units (APUs) are accommodated within the main landing gear fairings.[9] As a consequence of the heat and blast effects produced by these APUs, some airports require pavement protection to be deployed.[34] The landing gear of the An-124 is outfitted with an oleo strut suspension system for its 24 wheels. This suspension has been calibrated to allow for landing on rough terrain and is able to kneel, which allows for easier loading and unloading via the front cargo door.[29][9] Other features intended to ease loading including an onboard overhead crane in the cargo deck, capable of lifting up to 30 tonnes, while items up to 120 tonnes can be winched on board.[35][9] Two separate radar units are typically present, one is intended for ground mapping and navigation purposes, while the other is for weather.[9]

Operational history

During the 2000s, Germany headed an initiative to lease An-124s for NATO strategic airlift requirements. Two aircraft were leased from SALIS GmbH as a stopgap until the Airbus A400M became available.[36] Under NATO SALIS programme NAMSA is chartering six An-124-100 transport aircraft. According to the contract An-124-100s of Antonov Airlines and Volga-Dnepr are used within the limits of NATO SALIS programme to transport cargo by requests of 18 countries: Belgium, Hungary, Greece, Denmark, Canada, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, United Kingdom, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Finland, France, Germany, Czech Republic and Sweden. Two An-124-100s are constantly based on full-time charter in the Leipzig/Halle airport, but the contract specifies that if necessary, two more aircraft will be provided at six days' notice and another two at nine days' notice.[37] The aircraft proved extremely useful for NATO especially with ongoing operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.[38]

United Launch Alliance (ULA) contracts the An-124 to transport the Atlas V launch vehicle from its facilities in Decatur, Alabama to Cape Canaveral. ULA also uses the An-124 to transport the Atlas V launch vehicle and Centaur upper stage from their manufacturing facility in Denver, Colorado to Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg Space Force Base.[39] Two flights are required to transfer each launch vehicle (one for the Atlas V main booster stage and another for the Centaur upper stage).[40] It is also contracted by Space Systems Loral to transport satellites from Palo Alto, CA to the Arianespace spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana[41] and by SpaceX to transport payload fairings between their factory in Hawthorne, California and Cape Canaveral.[42]

By 2013, the An-124 had reportedly visited 768 airports in over 100 countries.[43]

By late 2020, three civil operators of the An-124 remained. Antonov Airlines with seven aircraft, Volga-Dnepr Airlines with 12, and Maximus Air Cargo with one. In November 2020, Volga-Dnepr reported that it was indefinitely grounding its fleet of An-124 aircraft to inspect the 60 engines (including spares) following the 13 November 2020 unconfined engine failure at Novosibirsk.[44] As of 29 December 2020, the first Volga-Dnepr An-124-100 was back in service.[45]

Significant activities

_is_carefully_loaded_onto_a_Russian-built_An-124_Condor_(Antonov).jpg.webp)

- In May 1987, an An-124 set a world record, covering the distance of 20,151 km (10,881 nmi) without refuelling.[46] The flight took 25 hours and 30 minutes; the takeoff weight was 455,000 kg.

- In July 1985, an An-124 carried 171,219 kg (377,473 lb) of cargo to an altitude of 2,000 m (6,600 ft) and 170,000 kg to an altitude of 10,750 m (35,270 ft).[47]

- In June 1994, an An-124 flew the first IE 201 Class diesel-electric locomotive from the General Motors Diesel works in London, Ontario, Canada to Dublin, Ireland for clearance testing and crew training, before subsequent units were delivered by ship.[48]

- An An-124 was used to transport the Obelisk of Axum back to its native homeland of Ethiopia from Rome in April 2005.[49]

- An An-124 was used to transport an EP-3E Aries II electronic intelligence aircraft from Hainan Island, China on 4 July 2001 following the Hainan Island incident.

- An An-124 was used to transport the first Bombardier Movia-series railcar for the Delhi Metro on 26 February 2009.[50]

- In July 2010, an An-124 was used to transport four 35-foot and three 21-foot skimmer boats from France to the US to assist with the clean-up of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[51]

- An An-124 was used in April 2011 to airlift a large Putzmeister concrete pump from Germany to Japan to help cool reactors damaged in the Fukushima nuclear accident.[52] The An-225 was used to transport an even larger Putzmeister concrete pump to Japan from the US.[53]

- An An-124 was used in May 2018 to transport an 87,000 lb die tool from Eaton Rapids, Michigan, US to Nottingham, England to restart Ford F-150 production after a fire in the Eaton Rapids Magnesium Casting Facility.[54]

- Several An-124s were used by the German Bundeswehr to airlift military equipment from Mazar-i-Sharif to Leipzig during the 2021 German troop withdrawal from Afghanistan. Among the equipment were two NH-90 helicopters.[55][56]

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, several An-124s were used to cargo masks and other medical equipment from China to foreign countries. For example, Terio International Inc. dispatched their first one on June 7 2020 between Nanjing and Montréal, which was done as a direct flight.[57][58]

- On 24 February 2022, an An-124 with registration number UR-82009 was confirmed to be destroyed by Russian artillery during the Battle of Antonov Airport, Kyiv.[59] Five other Ukrainian An-124s were diverted to Leipzig at the conclusion of their commercial flights.[60]

- On 3 March 2023, an An-124 delivered 101 tons of humanitarian aid for earthquake victims in Turkey and Syria.[61][62]

- On 9 June 2023, an An-124 was seized by Canadian government authorities at Toronto Pearson Airport. It had been stranded following closure of Canadian airspace to Russian air navigation.[63]

Variants

- An-124 Ruslan

- Strategic heavy airlift transport aircraft

- An-124-100

- Commercial transport aircraft

- An-124-100M-150

- Version with a payload increased to 150 tonnes (maximum take-off weight 420 tonnes), with uprated Lotarev D-18T series 4 engines; one An-124-100 converted[64]

- An-124-102 Slon

- Commercial transport version with an EFIS flight deck, developed by TsAGi

- An-124-115M

- Planned new variant with EFIS based on Rockwell Collins avionic parts

- An-124-130

- Proposed version

- An-124-135

- Variant with one seat in the rear and the rest of the cargo area (approx. 1,800 square feet) dedicated to freight

- An-124-200

- Proposed version with General Electric CF6-80C2 engines, each rated at 59,200 lbf (263 kN)

- An-124-210

- Joint proposal with Air Foyle to meet UK's Short Term Strategic Airlifter (STSA) requirement, with Rolls-Royce RB211-524H-T engines, each rated 60,600 lbf (264 kN) and Honeywell avionics—STSA competition abandoned in August 1999, reinstated, and won by the Boeing C-17A.

- An-124-300

- The -300 is planned variant with upgraded engines with higher thrust. Variant was ordered by the Russian Aerospace Forces in 2020.[65]

Operators

Military

- Russian Aerospace Forces – 12 in service, 14 in reserve.[66] In 2008, a contract was signed with Aviastar-SP for modernization of 10 aircraft by 2015.[67] As of December 2019, at least 11 aircraft were modernized. 2 on order.[68][69][70][71][72][73]

- 12th Military Transport Aviation Division

- 566th Military Transport Aviation Regiment – Seshcha air base, Bryansk Oblast[74]

- 18th Military Transport Aviation Division[75]

- 235th Military Transport Aviation Regiment – Ulyanovsk Vostochny Airport, Ulyanovsk Oblast[76]

- 224th Air Detachment of Military Transport Aviation – Migalovo, Tver Oblast

- 12th Military Transport Aviation Division

Former military operators

- Soviet Air Force – aircraft were transferred to Russian and Ukrainian Air Forces after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Civil

_(2).jpg.webp)

As of late 2020, 20 An-124s were in commercial service.[11]

- Volga-Dnepr (12, with 3 on order)[6][77]

Former civil operators

- Libyan Arab Air Cargo – had 2 aircraft in service as of 2013;[6] 1 seized by Ukraine in 2017,[79] and 1 destroyed on ground by shelling at Mitiga International Airport in June 2019.[80]

- Aeroflot Russian International Airlines – retired from fleet in 2000

- Ayaks Cargo (Ayaks Polet Airlines)

- Polet Airlines – ceased operations 2014

- Rossiya Airlines – retired from fleet

- Transaero Airlines – retired from fleet

- Titan Cargo – company ceased operations 2002

- TransCharter Titan Cargo – ceased operations 2003

- Aeroflot Soviet Airlines – transferred to the Russian Aeroflot fleet

- Air Foyle (in partnership with Antonov Design Bureau) – joint venture dissolved 2006

- HeavyLift Cargo Airlines (in partnership with Volga-Dnepr Airlines) – ceased operations 2006

- Antonov AirTrack – ceased operations

Notable accidents

As of June 2019, five accidents with An-124 hull-losses have been recorded involving a total of 97 fatalities,[81][80] including:

- On 13 October 1992, CCCP-82002, operated by Antonov Airlines crashed near Kyiv, Ukraine during flight testing, suffering nose cargo door failure during high-speed descent (part of test program) resulting in total loss of control. The airplane came down in a forest near Kyiv, killing eight of the nine crew on board.[82]

- On 15 November 1993, RA-82071, operated by Aviastar Airlines crashed into a mountain at 11,000 feet (3,400 m) while in a holding pattern at Kerman, Iran. There were 17 fatalities.[83]

- On 8 October 1996, RA-82069, owned by Aeroflot but operated by Ayaks Cargo, crashed at San Francesco al Campo, Italy, while initiating a go-around after a low visibility approach on Turin Caselle airport's runway 36. There were four fatalities.[84]

- On 6 December 1997, RA-82005, operated by the Russian Air Force, crashed in a residential area after take-off in Irkutsk, Russia. All 23 people on board and 49 people on the ground were killed.[85]

- On 13 November 2020, the second engine of RA-82042, operated by Volga-Dnepr Airlines, suffered an uncontained engine failure after takeoff from Novosibirsk, Russia. Subsequently, after landing there, the aircraft suffered a runway excursion and the nose landing gear collapsed.[86] On 25 November, the airline voluntarily grounded its entire fleet of An-124 aircraft.[87] By 29 December, the first Volga-Dnepr An-124-100 was back in service.[45]

Specifications (An-124-100M)

Data from Jane's all the World's Aircraft 2006-07,[88] Volga-Dnepr[89]

General characteristics

- Crew: Eight (pilot, copilot, navigator, chief flight engineer, electrical flight engineer, radio operator, two loadmasters)

- Capacity: 88 passengers in upper aft fuselage, or the hold can take an additional 350 pax on a palletised seating system / 150,000 kg (330,693 lb)

- Length: 69.1 m (226 ft 8 in)

- Wingspan: 73.3 m (240 ft 6 in)

- Height: 21.08 m (69 ft 2 in)

- Wing area: 628 m2 (6,760 sq ft)

- Aspect ratio: 8.6

- Airfoil: TsAGI Supercritical[90]

- Empty weight: 181,000 kg (399,037 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 402,000 kg (886,258 lb) * Maximum landing weight: 330,000 kg (727,525 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 210,172 kg 463,343 lb 262,715.15 L (69,402.00 US gal; 57,789.25 imp gal)

- Powerplant: 4 × Progress D-18T high-bypass turbofan engines, 229 kN (51,000 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Cruise speed: 865 km/h (537 mph, 467 kn) max

- 800–850 km/h (500–530 mph; 430–460 kn) at FL 328-394 (32,800–39,400 ft (9,997–12,009 m) at regional pressure setting)

- Approach speed: 230–260 km/h (140–160 mph; 120–140 kn)

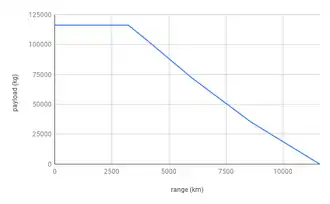

- Range: 3,700 km (2,300 mi, 2,000 nmi) with max payload

- 8,400 km (5,200 mi; 4,500 nmi) with 80,000 kg (176,370 lb) payload

- 11,500 km (7,100 mi; 6,200 nmi) with 40,000 kg (88,185 lb) payload

- Ferry range: 14,000 km (8,700 mi, 7,600 nmi) with max fuel and minimum payload

- Service ceiling: 12,000 m (39,000 ft) max certified altitude

- Wing loading: 640.1 kg/m2 (131.1 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.23

- Take-off run (maximum take-off weight): 3,000 m (9,800 ft)

- Landing roll (maximum landing weight): 900 m (3,000 ft)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Airbus Beluga

- Boeing 747-400F

- Boeing 747-8F

- Boeing C-17 Globemaster III

- Lockheed C-5 Galaxy

- Ilyushin PAK VTA

References

Citations

- "Era of Ruslan: 25 years" (Press release). Antonov. 24 December 2007. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- "An-124 Production List". russianplanes.net (in Russian). Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "AN-124-100 Performance". Antonov. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Although the enlarged An-124-100M-150 version has a 7% higher payload than the operational Boeing 747-8F, the 747-8F has over two times the range at 5,050 mi (8,130 km) with a payload of 295,800 lb (134,200 kg) compared to the An-124-100M-150 at the same payload. The An-124-100M-150 is able to carry less than half the payload at the same range.[3]

- Novichkov, Nikolai (2 December 2014). "Russia completes initial An-124 upgrade programme". janes.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "World Airliner Census". Flight International, 16–22 August 2013.

- "UPDATE: Time called on An-124 production re-start". IHS Jane's Defence Industry. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "Trends in Soviet Military Programs" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. October 1976. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2012.

originally Top Secret

- "The Condor: A New Soviet Heavy Transport" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2012.

originally classified Secret

- "Volga-Dnepr Group Celebrates 80th Birthday of Legendary Chief Designer of the An-124 and An-225 Transport Aircraft". Volga-dnepr.com. 24 December 1982. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018.

- Villamizar, Helwing (26 December 2021). "Today in Aviation: Maiden Flight of the Antonov An-124". Airways Magazine. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Fricker 1990, pp. 57-78.

- "Era of Ruslan: 25 years". Antonov. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- E. Gordon, Antonov's Heavy Transports, Midland Publishing.

- Kurapov, Herman A. (April 2006). "Strategic Airlifters: a Comprehensive Comparison between the Boeing C-17 and the Antonov An-124-100". casr.ca. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009.

- Norris, Guy (10 October 2018). "Freighter Growth And Possible An-124 Reengining Boost CF6 Prospects". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- "Ukraine, Russia to resume production of giant cargo planes". Forbes. Kyiv. Thomson Financial. 28 April 2008. Archived from the original on 30 August 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- Taverna, Michael A. "Russia, Ukraine Near Deal on Relaunch of Modernized An-124". Berlin, Germany: Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max (7 May 2009). "Superjet the biggest casualty as Russia slashes airliner output plans". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- Maternovsky, Dennis (24 December 2009). "Russia to Resume Making World's Largest Plane, Kommersant Says". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

- "(Archived copy)". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Antonov resumes the production of An-124 Ruslan without Russia". Airlinerwatch. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- Karnozov, Vladimir (4 February 2019). "An-124 Ruslan Replacement Takes Shape". AIN online. Archived from the original on 6 February 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "An-124 Ruslan (Condor) Large Cargo Aircraft". 12 May 2018.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (5 November 2019). "Windtunnel beckons for An-124 successor". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "В ЦАГИ изготовлена аэродинамическая модель большегрузного транспортного самолета "Слон"". Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Rogoway, Tyler (5 November 2019). "Russia Shows Wind Tunnel Model Of An "Elephant" Airlifter Replacement For The An-124". The Drive. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "В ЦАГИ прошли испытания модели самолета "Слон" - Новости - Пресс-центр - ЦАГИ".

- "Air Force Technology - Air Force Technology - An-124 Condor - Long Range Heavy Transport Aircraft". Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Fricker 1990, p. 78.

- Antonov's Heavy Transports. Midland Publishing.

- Phillips, W. Scott (31 August 1999). "Fixed-Wing Aircraft". Federation of American Scientists Military Analysis Network. Archived from the original on 27 February 2006. Retrieved 22 February 2006.

- "AVIATION Reports – 2000 – A00O0279". Transportation Safety Board of Canada. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

The AN124 has been described by training personnel and pilots as being very easy to handle for an aircraft of its size. The AN124 tends to be very light on the controls

- Nielsen, Erik. "Copenhagen Airport, Use of auxiliary power unit (APU)". Copenhagen Airport / Boeing. p. 6.5. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- "An124-100 technical specification". Ruslan International. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- "Strategic airlift agreement enters into force". NATO Update. 23 March 2006. Archived from the original on 7 April 2006. Retrieved 7 April 2006.

- "Strategic Airlift Interim Solution (SALIS)". NATO. Archived from the original on 9 May 2009.

- "Antonov An-124 NATO SALIS Program Extended Through End of 2010". deagel.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012.

- "Lockheed Martin Atlas rocket". The History Channel. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010.

- "Lockheed Martin Delivers Atlas V to Cape Canaveral for NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Mission". Ilslaunch. 4 April 2005. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017.

- "Space Systems/Loral Delivers World'S Largest Satellite To Launch Base". Archived from the original on 9 March 2008.

- "Ukraine's Antonov helps SpaceX transport rocket hardware". Ukrinform. Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "30 years since the AN-124 Ruslan maiden take-of". Antonov.com. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Lennane, Alex (25 November 2020). "'Safety first' as Volga-Dnepr grounds its AN-124 fleet indefinitely". The Loadstar. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Brett, Damian (30 December 2020). "First Volga-Dnepr AN-124 back in the air". Aircargo News. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- "Оружие России; Ан-124 "Руслан" (Condor), дальний тяжелый военно-транспортный самолет". Archived from the original on 3 June 2009.

- "Аэрокосмическое общество Украины; Международная авиационная федерация зарегистрировала 124 мировых рекорда, установленных на самолёте Ан-225". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- "Locomotive Makes Aviation History". Journal of Commerce. 31 July 1994. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- "Obelisk arrives back in Ethiopia". BBC News. 19 April 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Delhi Metro's first rake to be airlifted was carried on a Ukraine-made aircraft". Business Today. 23 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Chapman Freeborn delivers skimmer boats to Gulf of Mexico | eft - Supply Chain & Logistics Business Intelligence". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- "Germany sends giant pump to help cool Fukushima reactor". monstersandcritics.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- "SRS pump will head to Japan". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "Ford's plan to rescue F-150: Drama worthy of a James Bond script". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018.

- "Bundeswehrabzug kommt in Schwung: An-124 holt NH90 aus Afghanistan". www.flugrevue.de (in German). 18 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Abzug aus Afghanistan – Die heiße Phase hat begonnen I Bundeswehr, archived from the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 20 May 2021

- Élise, Paradis; Thériault, Vincent; Thériault, François (November 2021). Made-To-Deliver: An inspiring entrepreneurial story of boldness and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic (1st ed.). Quebec, Canada: Self-Published. ISBN 979-8-4824-0659-5.

- Gagné, Louis (16 November 2021). "« Tailler sa place » : récit d'une réussite entrepreneuriale en contexte pandémique". Radio Canada. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- "Antonov's sources claim that the world's largest aircraft An-225 Mriya was destroyed". sproutwired.com. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- Ponomarenko, Illia (15 April 2022). "Chief pilot of destroyed An-225: 'We must complete the second Mriya'". The Kyiv Independent. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- "Ukrainian aircraft delivers 101 tons of humanitarian aid to Turkey for earthquake victims". Espreso TV. 3 March 2023. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- 39th Air Base Wing (3 March 2023). "Antonov An-124 delivered 101 tons of humanitarian aid to earthquake-raged Türkiye". twitter.com. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- "Government of Canada orders seizure of Russian-registered cargo aircraft at Toronto Pearson Airport". Global Affairs Canada.

- "[Actu] Les Antonov An-124-100 en Russie". Red Samovar. 4 April 2020.

- https://zvezdaweekly.ru/news/202011161330-mKqdi.html

- "Антонов Ан-124". russianplanes.net. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Петр Бутовски об Ан-124 "Руслан"" [Peter Butovskaya about AN-124 "Ruslan"] (in Russian). bmpd.livejournal.com. 9 May 2013. Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ""Авиастар-СП" успешно выполнил гособоронзаказ на модернизацию шести самолетов Ан-124-100 "Руслан"". armstrade.org. 24 November 2014. Archived from the original on 5 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Modernization of another An-124-100 "Ruslan" completed". engineeringrussia.wordpress.com. 13 July 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Именной Ан-124-100 "Руслан" "Олег Антонов" совершил ознакомительный полет после модернизации". armstrade.org. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / "Авиастар-СП" продлил ресурс летной годности и передал в эксплуатацию самолет Ан-124-100 "Руслан"". Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / "Авиастар-СП" продлил ресурс летной годности очередному самолету Ан-124-100 "Руслан"". Archived from the original on 10 September 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "ЦАМТО / Новости / Продлен ресурс летной годности очередного самолета Ан-124-100 "Руслан"". Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "566th Solnechnogorskiy Red Banner order of Kutuzov Military-Transport Aviation Regiment". ww2.dk. Archived from the original on 4 June 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "В ВКС России восстановлена 18-я военно-транспортная авиационная дивизия". bmpd.livejournal.com. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "В Ульяновске восстановлен 235-й военно-транспортный авиационный полк". bmpd.livejournal.com. 3 December 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- "Fleet in Flight Radar". Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Some of the biggest planes in the world were in Kiev at the time of the invasion, see what they are". The Goa Spotlight. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "Ukraine to auction Libya's An-124 Ruslan if Libya fails to pay $1.2 million of debt for aircraft servicing". en.interfax.com.ua. 13 October 2017. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- "5A-DKN hull-loss incident". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- "ASN Aviation Safety Database: Antonov 124-100". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Accident Description, Anotonov 124-100, Tuesday 13 October 1992". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Accident Description, Antonov 124-100, Monday 15 November 1993". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Accident Description, Antonov 124-100, Tuesday 8 October 1996". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- Velovich, Alexander (17 December 1997). "Multiple engine failure blamed for An-124 Irkutsk accident". Moscow, Russia: Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- "Accident Description, Anotonov 124-100, Friday 13 November 2020". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Field, James (25 November 2020). "Volga-Dnepr Grounds Antonov An-124 Fleet Indefinitely". Airways Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Jackson 2005, pp. 569–571.

- "An-124 Specs" (PDF). Volga-Dnepr.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Fricker, John (February 1990). "Heavy Lifters". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 167, no. 2. Hearst Magazines. ISSN 0032-4558.

- Jackson, Paul, ed. (2005). Jane's all the World's Aircraft 2006-07 (97th ed.). London: Jane's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7106-2745-2. OCLC 70112997.

Further reading

- Yeltsov, Gennady (2011). Antonov AN-124: A Tale of Air Supremacy. JustplanesUK. ISBN 978-0-9569328-0-8.

External links

| External video | |

|---|---|

![]() Media related to Antonov An-124 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antonov An-124 at Wikimedia Commons