Apothecary

Apothecary (/əˈpɒθəkəri/) is an archaic English term for a medical professional who formulates and dispenses materia medica (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms 'pharmacist' and 'chemist' (British English) have taken over this role.

In some languages and regions, "apothecary" is not archaic and has become those languages' term for "pharmacy" or a pharmacist who owns one.

Apothecaries' investigation of herbal and chemical ingredients was a precursor to the modern sciences of chemistry and pharmacology.[1]

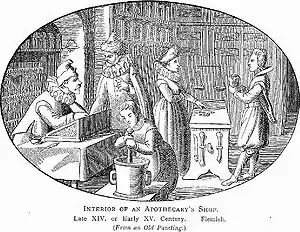

In addition to dispensing herbs and medicine, apothecaries offered general medical advice and a range of services that are now performed by other specialist practitioners, such as surgeons and obstetricians.[2] Apothecary shops sold ingredients and the medicines they prepared wholesale to other medical practitioners, as well as dispensing them to patients.[3] In 17th-century England, they also controlled the trade in tobacco which was imported as a medicine.[4]

Etymology

The term "apothecary" derives from the Ancient Greek ἀποθήκη (apothḗkē, "a repository, storehouse") via Latin apotheca ("repository, storehouse, warehouse", cf. bodega and boutique), Medieval Latin apothecarius ("storekeeper"), and eventually Old French apotecaire.[5]

In some European and other languages, the term is current and used to designate a pharmacist/chemist, such as German and Dutch Apotheker,[6] Latvian aptiekārs and Luxembourgish Apdikter.[7] Likewise, "pharmacy" translates as apotek in Danish,[8] Norwegian[9][10] and Swedish, apteekki in Finnish, apoteka in Bosnian, aptieka in Latvian, апотека (apoteka) in Serbian, аптека (apteka) in Russian, Bulgarian, Macedonian and Ukrainian, Apotheke in German and apteka in Polish.[11] The word in Indonesian is apoteker,[12] which was borrowed from the Dutch apotheker.[13] In Yiddish the word is אַפּטייק apteyk.

Use of the term in the names of businesses varies with time and location. It is generally an Americanism, though some areas of the United States use it to invoke an experience of nostalgic revival and it has been used for a wide variety of businesses; while in other areas such as California its use is restricted to licensed pharmacies.[14]

History

The profession of apothecary can be dated back at least to 2600 BC to ancient Babylon, which provides one of the earliest records of the practice of the apothecary. Clay tablets have been found with medical texts recording symptoms, prescriptions, and the directions for compounding.[15]

In ancient India, the Sushruta Samhita, a compendium on the practice of medicine and medical formulations, has been traced back to the 1st century BC.[16]

The Papyrus Ebers from ancient Egypt, written around 1500 BC, contain a collection of more than 800 prescriptions. It lists over 700 different drugs.[15][17]

The Shen-nung pen ts'ao ching, a Chinese book on agriculture and medicinal plants (3rd century AD),[18][15][19] is considered a foundational material for Chinese medicine and herbalism and became an important source for Chinese apothecaries.[20] The book, which documented 365 treatments, had a focus on roots and grass. It had treatments which came from minerals, roots and grass, and animals.[18][19] Many of the mentioned drugs and their uses are still followed today. Ginseng's use as a sexual stimulant and aid for erectile dysfunction stems from this book.[21] Ma huang, an herb first mentioned in the book, led to the introduction of the drug ephedrine into modern medicine.[18]

According to Sharif Kaf al-Ghazal,[22] and S. Hadzovic,[23] apothecary shops existed during the Middle Ages in Baghdad,[22] operated by pharmacists in 754 during the Abbasid Caliphate, or Islamic Golden Age.[23] Apothecaries were also active in Al-Andalus by the 11th century.[24]

By the end of the 14th century, Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1342–1400) was mentioning an English apothecary in the Canterbury Tales, specifically "The Nun's Priest's Tale" as Pertelote speaks to Chauntecleer (lines 181–184):

... and for ye shal nat tarie,

Though in this toun is noon apothecarie,

I shal myself to herbes techen yow,

That shul been for youre hele and for youre prow.

In modern English, this can be translated as:

... and you should not linger,

Though in this town there is no apothecary,

I shall teach you about herbs myself,

That will be for your health and for your pride.

In Renaissance Italy, Italian Nuns became a prominent source for medicinal needs. At first they used their knowledge in non-curative uses in the convents to solidify the sanctity of religion among their sisters. As they progressed in skill they started to expand their field to create profit. This profit they used towards their charitable goals. Because of their eventual spread to urban society, these religious women gained "roles of public significance beyond the spiritual realm (Strocchia 627).[25] Later apothecaries led by nuns were spread across the Italian peninsula.

From the 15th century to the 16th century, the apothecary gained the status of a skilled practitioner. In England, the apothecaries merited their own livery company, the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, founded in 1617.[26][27] Its roots, however, go back much earlier to the Guild of Pepperers formed in London in 1180.[28]

However, there were ongoing tensions between apothecaries and other medical professions, as is illustrated by the publication of 'A Short View of the Frauds and Abuses Committed by Apothecaries' by the Physician Christopher Merrett in 1669[30] and the experiences of Susan Reeve Lyon and other women apothecaries in 17th century London.[3] Often women (who were prohibited from entering medical school) became apothecaries which took away business from male physicians.[31] In 1865 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became the first woman to be licensed to practice medicine in Britain by passing the examination of the Society of Apothecaries.[32] By the end of the 19th century, the medical professions had taken on their current institutional form, with defined roles for physicians and surgeons, and the role of the apothecary was more narrowly conceived, as that of pharmacist (dispensing chemist in British English).[33]

In German-speaking countries, such as Germany, Austria and Switzerland, pharmacies or chemist stores are still called apothecaries or in German Apotheken. The Apotheke ("store") is legally obligated to be run at all times by at least one Apotheker (male) or Apothekerin (female), who actually has an academic degree as a pharmacist – in German Pharmazeut (male) or Pharmazeutin (female) – and has obtained the professional title Apotheker by either working in the field for numerous years, usually by working in a pharmacy store, or taking additional exams. Thus a Pharmazeut is not always an Apotheker.[34] Magdalena Neff became the first woman to gain a medical qualification in Germany when she studied pharmacy at the Technical University of Karlsruhe and later passed the apothecary's examination in 1906.[35]

Apothecaries used their own measurement system, the apothecaries' system, to provide precise weighing of small quantities.[36] Apothecaries dispensed vials of poisons as well as medicines, and as is still the case, medicines could be either beneficial or harmful if inappropriately used. Protective methods to prevent accidental ingestion of poisons included the use of specially-shaped containers for potentially poisonous substances such as laudanum.[37]

Apothecary work as gateway to women as healers

Apothecary businesses were typically family-run, and wives or other women of the family worked alongside their husbands in the shops, learning the trade themselves. Women were still not allowed to train and be educated in universities so this allowed them a chance to be trained in medical knowledge and healing. Previously, women had some influence in other women's healthcare, such as serving as midwives and other feminine care in a setting that was not considered appropriate for males. Though physicians gave medical advice, they did not make medicine, so they typically sent their patients to particular independent apothecaries, who did also provide some medical advice, in particular remedies and healing.

Methods

Recipes

Many recipes for medicines included herbs, minerals, and pieces of animals (meats, fats, skins) that were ingested, made into paste for external use, or used as aromatherapy. Some of these are similar to natural remedies used today, including catnip,[38] chamomile, fennel, mint, garlic, and witch hazel.[39] Many other ingredients used in the past such as urine, fecal matter, earwax, human fat, and saliva, are no longer used and are generally considered ineffective or unsanitary.[40] Trial and error were the main source for finding successful remedies, as little was known about the chemistry of why certain treatments worked. For instance, it was known that drinking coffee could help cure headaches, but the existence and properties of caffeine itself was still a mystery.[41]

Noted apothecaries

See also

References

- Awofeso, N. (2013). Organisational capacity building in health systems. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 9780415521796. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- King, H. (2007). Midwifery, obstetrics and the rise of gynaecology: The uses of a sixteenth-century compendium. Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate. p. 80. ISBN 9780754653967. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Woolf, J.S. (2009). "Women's business: 17th-century female pharmacists". Chemical Heritage Magazine. 27 (3): 20–25. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Gately, I. (2001). Tobacco: A cultural history of how an exotic plant seduced civilization. New York: Grove Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0802139603. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Harper, Douglas. "apothecary". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "Apotheker - Van Dale". vandale.nl. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- "Apdikter". Lëtzebuerger Online Dictionnaire. Ministère de la Culture. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "apotek — Den Danske Ordbog". ordnet.dk. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- "apteka – Słownik języka polskiego PWN". sjp.pwn.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2019-09-17.

- "Hasil Pencarian - KBBI Daring". kbbi.kemdikbud.go.id. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- "apotek - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- Friedman, N. (2014). "Going medieval: The revival of "apothecary"". Visual Thesaurus. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Allen, L. Jr. (2011). "A history of pharmaceutical compounding" (PDF). Secundum Artem. 11 (3). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-28. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Meulenbeld, G. J (2000). A history of Indian medical literature. Vol. IA. Groningen. pp. 342–344. ISBN 90-6980-124-8. OCLC 872371654.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - American Botanical Council. (1998). "A pictorial history of herbs in medicine and pharmacy". Herbalgram (42): 33–47.

- Pursell, J. (2015). The herbal apothecary: 100 medicinal herbs and how to use them. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon ISBN 978-1604695670

- US National Library of Medicine. “Shen Nung, the Divine Husbandman.” Classics of Traditional Chinese Medicine, from the History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, an online version of an exhibit held at the NLM, Nationals Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD October 19, 1999-May 30, 2000.

- Pursell, J. (2015). The herbal apothecary: 100 medicinal herbs and how to use them. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. pp. 3–14. ISBN 978-1604695670.

- Chuncai, Z. (2002). Illustrated yellow emperor's canon of medicine (Chinese/English ed.). Dolphin Books. ISBN 978-7800518171.

- Al-Ghazal, S.K. (2004). "The valuable contributions of Al-Razi (Rhazes) in the history of pharmacy during the Middle Ages", Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, 3(6), pp. 9-11.

- Hadzović, S. (1997). "Pharmacy and the great contribution of Arab-Islamic science to its development". Medicinski Arhiv (in Croatian). 51 (1–2): 47–50. ISSN 0350-199X. OCLC 32564530. PMID 9324574.

- Harley, J.B.; Woodward, D. (1992). The history of cartography. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-226-31635-2.

- Strocchia, S.T. (2011). "The nun apothecaries of Renaissance Florence: Marketing medicines in the convent". Renaissance Studies. 25 (5): 627–647. doi:10.1111/j.1477-4658.2011.00721.x. S2CID 152957502.

- Barrett, C.R.B. (1905). The history of the society of apothecaries of London. London: E. Stock.

I shall endeavour to trace the history of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London, from its incorporation as a separate body on December 6, 1617, down to the present day.

- Copeman, W.S. (1967). "The worshipful society of apothecaries of London--1617-1967". Br Med J. 4 (5578): 540–541. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5578.540. PMC 1749172. PMID 4863972.

- "Origins". The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London. Archived from the original on 2016-11-11. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- "The Lady Apothecary". The Walters Art Museum.

- Merrett, Christopher (1669). "A Short View of the Frauds and Abuses Committed by Apothecaries". Project Gutenberg. Archived from the original on 2006-05-24. Retrieved 2021-03-26.

- Green, Monica (1989). "Women's Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe". Signs. 14 (2): 434–473. doi:10.1086/494516. JSTOR 3174557. PMID 11618104. S2CID 38651601.

- Porrirr, A.G. (1919). "Reviewed work: The life of Sophia Jex-Blake, by Margaret Todd". Political Science Quarterly. 34 (1): 180. JSTOR 2141537.

- Liaw, S.T.; Peterson, G. (2009). "Doctor and pharmacist - back to the apothecary!". Australian Health Review. 33 (2): 268–78. doi:10.1071/ah090268. PMID 19563315.

- "German Pharmacy, Apotheke, vs Drogerie". Journey to Germany. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Beisswanger, G.; Hahn, G.; Seibert, E.; Szász, I.; Trischler, C. (2001). Frauen in der Pharmazie: Die Geschichte eines Frauenberufs. Stuttgart: Deutscher Apotheker Verlag.

- Cazalet, S. (2001). "Tables of weights and measures. Apothecaries' weight". HOMÉOPATHE INTERNATIONAL.

- Griffenhagen, G.; Bogard, M. (1999). History of drug containers and their labels. Madison, Wisconsin: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy. p. 35. ISBN 978-0931292262. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Wilson, R.C. (2010). Drugs and pharmacy in the life of Georgia, 1733-1959. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0820335568. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Allen, D.E.; Hatfield, G. (2004). Medicinal plants in folk tradition: An ethnobotany of Britain & Ireland. Portland (Or.) [etc.]: Timber Press. ISBN 9780881926385.

- Douglas, J. (2008). "Remedies and recipes". Writing the Renaissance. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Trifone, N. (2017). "A Dose of Expertise". Retrieved 8 October 2017.

External links

- "On Keeping Shop: A Guidebook for Preparing Orders" is a book, in Arabic, from 1260 that extensively discusses the art of being an apothecary