Apthorp Farm

The Apthorp Farm that lay on Manhattan's Upper West Side straddled the old Bloomingdale Road, laid out in 1728, which was re-surveyed as The "Boulevard" – now Upper Broadway. It was the largest block of real estate remaining from the "Bloomingdale District", a rural suburb of 18th-century New York City. Legal disputes between the eventual heirs of the Loyalist Charles Ward Apthorp and purchasers of parcels of real estate held in abeyance the speculative development of the area between 89th and 99th Streets, from Central Park to the Hudson River until final judgment was awarded in July 1910; at that time the New York Times estimated its worth at $125,000,000.[1]

History

Charles Ward Apthorp Jr. (1729–1797) was the eldest son of prominent and wealthy Boston-born British agent Charles Apthorp in Massachusetts. He assembled the property in Manhattan through purchases in 1762 and 1763. In 1764 he built for himself an ambitious house, one of the grandest pre-Revolutionary houses on the island, on the rise of ground between what are now 90th and 91st Streets, and Columbus and Amsterdam Avenues, with a lane forty-feet wide extending down to the Bloomingdale Road.[2] The New York Times observed in 1910 "Had this tract been handed down from son to son on the British landed gentry system the owner to-day would virtually be New York's Duke of Westminster."[1] The house gained its name of "Elmwood" from the mature American elms that shaded it until it was demolished in 1891 to make way for 91st Street, having served for decades as a beer garden, public inn and picnic grounds called "Elm Park".

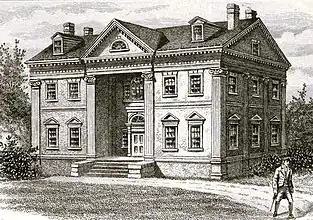

Apthorp's house faced the Hudson River, whose far shore and the Hudson Palisades were visible from its elevated position. It stood on a fieldstone service basement lit from a light well that surrounded the house. Six steps led to a wide and deeply recessed entrance bay and an arch-headed main door with flanking windows united by a common cornice, the "Palladian window". A similar grouping over it lit the central upper hall. On either side there were two flanking bays with pedimented window surrounds on the grand main floor and square three-over-three windows on the bedroom floor. There were two dormer windows in the attic. At each corner was a colossal fluted Ionic pilaster; the architecturally correct entablature was carried straight across the eaves, broken slightly forward over the entrance bay, where it was surmounted by a pediment. Ionic pilasters marched across the end fronts, three bays deep, whose gables were treated as pediments. The wooden siding was scored to imitate ashlar masonry.

It seems that such an unusual design has been adapted from an engraving in one of the illustrated architectural guides, addressed to gentlemen and builders alike, that by 1767 could have filled a library shelf. One such book owned by Charles Ward Apthorp is known, for he inscribed his name and the date 1759 in a copy of a translation of Sébastien Leclerc's architectural treatise that was published in London as A Treatise of Architecture, with Remarks and Observations By that Excellent Master thereof Sébastien Leclerc, Knight of the Empire, Designer and Engraver to the Cabinet of the late French King... Its four dedications were to the Worshipful Companies of Carvers, Joyners, Bricklayers and Masons of London, each represented by their coat-of-arms. The book passed to Apthorp's nephew, the architect Charles Bulfinch.[3] The ultimate source for all such neo-Palladian five-bay villas with recessed loggia entrances under a pediment, is Palladio's own Villa Emo.

Apthorp had been appointed to the Governor's Council the previous year, a position he held right through the British occupation of New York, until the 1783 evacuation, earning him the fierce opprobrium of his Patriot neighbors.

Aside from his private drive, Apthorp laid out cross-lanes on his farm, long known as Stryker's Lane and Jauncey's Lane. Jauncey's Lane gained its name from the rich Englishman, William Jauncey, who purchased Apthorp's "Elmwood". Also called "Apthorp's Lane" or simply the "Crossroad to Harlem, it extended eastwards to Harlem Commons[4] later taken into Central Park. The Crossroad to Harlem had a part to play in the Battle of Harlem Heights, 16 September 1776, for it was the route the British General Clinton took after marching up from the city along the Boston Post Road, in cutting across the island; they failed to intercept Silliman's brigade of militia, toiling up the Bloomingdale Road to rejoin the American troops at twilight.[5] The picturesque and leafy lanes marked property boundaries when he left his estate of some 200 acres (0.81 km2) among his ten children, but they were abolished, on paper at least, by the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 that laid out the present grid plan of Manhattan, which, it was assumed, would take more than a century to build upon. Early suits over the property were brought as early as 1799, and final litigation among the Apthorp heirs, and their assigns who had purchased parcels of the Apthorp property, for building rights over the former route of the Bloomingdale Road and lanes abandoned by the city, in order to close them once and for all, dragged on for five years, 1905–1911.

The ghostly passage of the lanes can still be detected; that of Jauncey's Lane subsists in the mid-block break between apartment buildings fronting Broadway just north of the northwest corner of 91st Street and running diagonally west to West End Avenue, and formerly all the way to Riverside Drive,[1] and that of Stryker's Lane in the similar gap between 93rd and 94th Streets, once running to the house built by Gerrit Stryker overlooking Stryker's Bay, a river landing now represented by infilled parkland of Riverside Park at the foot of 96th Street and the river.

The original divisions were carefully made by Apthorp's Patriot son-in-law Hugh Williamson, who had married Maria Apthorp at Elmwood, 3 January 1789.[6]

Elm Park

For a time in the mid- to late-19th century, until 1891, the mansion and its grounds, between 90th and 92nd Streets and Ninth (now Columbus) and Tenth (now Amsterdam) Avenues,[7] served as a beer garden, inn and picnic ground known as "Elm Park", a venue that was favored by the large German immigrant community in Manhattan.[8] It was also used as a parade ground by the 69th Regiment in 1855.[9] In 1870, it was the site of the first Orange riot, in which Irish Protestants and Irish Catholics clashed, killing 8 people.

The Apthorp

The Apthorp, the grand apartment block that commemorates Apthorp's name, was built in 1908 on the site of a house built in the 1760s by Apthorp and sold in 1767 to his brother-in-law (via both his wife and sister) James McEvers, with its "houses, outhouses, kitchens, barns and stables." McEvers' heirs sold it in 1792 to the second wife of John C. (Jan Cornelius) Van den Heuvel; following her death in 1792 he became Apthorp's son-in-law when he married Charlotte Augusta Apthorp. In 1827 his heirs sold the property, extending down to the Hudson River, before long to become a right-of-way for the Hudson River Railroad. William Burnham rented it from 1839, maintaining it as the somewhat genteel roadhouse called "Burnham's Mansion House"[10] A large parcel of the southern part of the Apthorp farm extending north to 89th Street, was purchased in 1860 by the real estate magnate William B. Astor whose son, John Jacob Astor III, had married the Van den Heuvel's granddaughter, Charlotte Gibbes. The Van den Heuvel house, partly rebuilt after a fire but as "Burnham's" still occupying a full city lot between 78th and 79th Streets, west of Broadway to West End Avenue, was purchased by William Waldorf Astor, son of John Jacob Astor III and second great grandson to Charles Ward Apthorp Jr., in 1878.[11]

References

Notes

- "The Famous Apthorp Farm Litigation Finally Ended", New York Times July 31, 1910, has provided much of the information in this article.

- (New York Public Library) 19th-century woodcuts and ca 1891 photograph of Apthorp's "Elmwood"; the photograph shows that the woodcuts, one from Booth's History of New York, are inaccurate in their details.

- Bulfinch, Ellen Susan. The Life and Letters of Charles Bulfinch, Architect (Boston, 1896) "Preface", p. 83f; the book remained with the Bulfinch family. The extended title page noted by Ms Bulfinch, the architect's grand-daughter, corresponds to an edition of 1734 of the translation by Ephraim Chambers printed for Richard Ware, London: title page illustrated. The volume remained with the Bulfinch family. Other American copies were in the libraries of Peter Harrison of Newport, Rhode Island, and the Salem Library Company, Massachusetts. Kenneth Hafertepe and James F. O'Gorman, American Architects and Their Books to 1848, (University of Massachusetts) 2001, p. 7, without identifying the edition of Le Clerc, note in this context that "the Bulfinch library at Cambridge includes also a 1759 edition of John Miller's Andrea Palladio's Elements of Architecture which bears no signature".

- Reports of Cases Heard and Determined in the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, 1904 "Van Winkle v. Van Winkle" p. 605-15

- Johnston, Henry Phelps. The Battle of Harlem Heights, (London, 1897) p. 41.

- Report in New-York Gazette, January 5, 1789, reprinted in the New York Times, July 31, 1910.

- "Historical map of the area". Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

- Orr, John W. The Manhattan vol. 4 (1884), p.54

- "The Lost 1764 Apthorpe Mansion"

- A detailed history of the house was published by Hopper Striker Mott in Valentine's Manual of Old New York, 1917, pp. 159-70.

- Trager, James. The New York Chronology, (New York: HarperCollins) 2003, s.v. "1860".

Further reading

- Stokes, I. N. Phelps, The Iconography of Manhattan Island 1498–1909, (v. 6) (New York : Robert H. Dodd, 1915–1928.) Cf. p. 95 on Charles Ward Apthorp, original grants and farms.

External links

Media related to Apthorp Mansion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Apthorp Mansion at Wikimedia Commons