History of Uruguay

The history of Uruguay comprises different periods: the pre-Columbian time or early history (up to the 16th century), the Colonial Period (1516–1811), the Period of Nation-Building (1811–1830), and the history of Uruguay as an independent country (1830).

| History of Uruguay |

|---|

|

|

|

Native

The earliest traces of human presence are about 10,000 years old and belong to the hunter-gatherer cultures of Catalanense and Cuareim cultures, which are extensions of cultures originating in Brazil. The earliest discovered bolas is about 7,000 years old. Examples of ancient rock art have been found at Chamangá. About 4,000 years ago, Charrúa and Guarani people arrived here. During precolonial times, Uruguayan territory was inhabited by small tribes of nomadic Charrúa, Chaná, Arachán, and Guarani peoples who survived by hunting and fishing and probably never reached more than 10,000 to 20,000 people. It is estimated that there were about 9,000 Charrúa and 6,000 Chaná and Guaraní at the time of first contact with Europeans in the 1500s. The native peoples had almost disappeared by the time of Uruguay's independence as a result of European diseases and constant warfare.[1]

European genocide culminated on 11 April 1831 with the Massacre of Salsipuedes, when most of the Charrúa men were killed by the Uruguayan army on the orders of President Fructuoso Rivera. The remaining 300 Charrúa women and children were divided as household slaves and servants among Europeans.

Colonization

During the colonial era, the present-day territory of Uruguay was known as Banda Oriental (east bank of River Uruguay) and was a buffer territory between the competing colonial pretensions of Portuguese Brazil and the Spanish Empire. The Portuguese first explored the region of present-day Uruguay in 1512–1513.[2]

The first European explorer to land there was Juan Díaz de Solís in 1516, but he was killed by natives. Ferdinand Magellan anchored at the future site of Montevideo in 1520. Sebastian Cabot in 1526 explored Río de la Plata, but no permanent settlements were established at that time. The absence of gold and silver limited the settlement of the region during the 16th and 17th centuries. In 1603, cattle and horses were introduced by the order of Hernando Arias de Saavedra, and, by the mid-17th century, their number had greatly multiplied. The first permanent settlement on the territory of present-day Uruguay was founded by Spanish Jesuits in 1624 at Villa Soriano on the Río Negro, where they tried to establish a Misiones Orientales system for the Charrúas.

_(cropped).png.webp)

In 1680, Portuguese colonists established Colônia do Sacramento on the northern bank of La Plata river, on the opposite coast from Buenos Aires. Spanish colonial activity increased as Spain sought to limit Portugal's expansion of Brazil's frontiers. In 1726, the Spanish established San Felipe de Montevideo on the northern bank and its natural harbor soon developed into a commercial center competing with Buenos Aires. They also moved to capture Côlonia del Sacramento. The 1750 Treaty of Madrid secured Spanish control over Banda Oriental, settlers were given land here and a local cabildo was created.

In 1776, the new Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata was established with its capital at Buenos Aires, and it included the territory of Banda Oriental. By this time, the land had been divided among cattle ranchers, and beef was becoming a major product. By 1800, more than 10,000 people lived in Montevideo and another 20,000 in the rest of the province. Out of these, about 30 percent were African slaves.[3]

Uruguay's early 19th-century history was shaped by an ongoing conflict between the British, Spanish, Portuguese, and local colonial forces for dominance of the La Plata Basin. In 1806 and 1807, during the Anglo-Spanish War (1796–1808), the British launched invasions. Buenos Aires was taken in 1806 and then liberated by forces from Montevideo led by Santiago de Liniers. In a new and stronger British attack in 1807, Montevideo was occupied by a 10,000-strong British force. The British forces were unable to invade Buenos Aires for the second time, however, and Liniers demanded the liberation of Montevideo in the terms of capitulation. The British gave up their attacks when the Peninsular War turned Great Britain and Spain into allies against Napoleon.[4]

Struggle for independence, 1811–1828

Provincial freedom under Artigas

The May Revolution of 1810 in Buenos Aires marked the end of Spanish rule in the Vice-royalty and the establishment of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. The Revolution divided the inhabitants of Montevideo between royalists, who remained loyal to the Spanish crown (many of which remained so), and revolutionaries, who supported the independence of the provinces from Spain. This soon led to the First Banda Oriental campaign between Buenos Aires and the Spanish viceroy.

Local patriots under José Gervasio Artigas issued the Proclamation of 26 February 1811, which called for a war against the Spanish rule. With the help from Buenos Aires, Artigas defeated Spaniards on 18 May 1811 at the Battle of Las Piedras and began Siege of Montevideo. At this point, Spanish viceroy invited Portuguese from Brazil to launch a military invasion of Banda Oriental. Afraid to lose this province to the Portuguese, Buenos Aires made peace with the Spanish viceroy. British pressure persuaded the Portuguese to withdraw in late 1811, leaving the royalists in control of Montevideo. Angered by this betrayal by Buenos Aires, Artigas, with some 4,000 supporters, retreated to Entre Ríos Province. During the Second Banda Oriental campaign in 1813, Artigas joined José Rondeau's army from Buenos Aires and started the second siege of Montevideo, resulting in its surrender to Río de la Plata.

Artigas participated in the formation of the League of the Free People, which united several provinces that wanted to be free from the dominance of Buenos Aires and create a centralized state as envisaged by the Congress of Tucumán. Artigas was proclaimed Protector of this League. Guided by his political ideas (Artiguism), he launched a land reform, dividing land to small farmers.

Brazilian province

The steady growth of the influence and prestige of the Liga Federal frightened the Portuguese government, which did not want the League's republicanism to spread to the adjoining Portuguese colony of Brazil. In August 1816, forces from Brazil invaded and began the Portuguese conquest of the Banda Oriental with the intention of destroying Artigas and his revolution. The Portuguese forces included a fully armed force of disciplined Portuguese European veterans of the Napoleonic Wars with local Brazilian troops. This army, with more military experience and material superiority, occupied Montevideo on 20 January 1817. In 1820, Artigas's forces were finally defeated in the Battle of Tacuarembó, after which Banda Oriental was incorporated into Brazil as its Cisplatina province. During the War of Independence of Brazil in 1823–1824, another siege of Montevideo occurred.

The Thirty-Three

On 19 April 1825, with the support of Buenos Aires, the Thirty-Three Orientals, led by Juan Antonio Lavalleja, landed in Cisplatina. They reached Montevideo on 20 May. On 14 June, in La Florida, a provisional government was formed. On 25 August, the newly elected provincial assembly declared the secession of Cisplatina province from Empire of Brazil and allegiance to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. In response, Brazil launched the Cisplatine War.

This war ended on 27 August 1828 when Treaty of Montevideo was signed. After mediation by Viscount Ponsonby, a British diplomat, Brazil and Argentina agreed to recognize an independent Uruguay as a buffer state between them. As with Paraguay, however, Uruguayan independence was not completely guaranteed, and only the Paraguayan War secured Uruguayan independence from the territorial ambitions of its larger neighbors. The Constitution of 1830 was approved in September 1829 and adopted on 18 July 1830.[5]

The "Guerra Grande", 1839–1852

Soon after achieving independence, the political scene in Uruguay became split between two new parties, both splinters of the former Thirty-Three: the conservative Blancos ("Whites") and the liberal Colorados ("Reds"). The Colorados were led by the first President Fructuoso Rivera and represented the business interests of Montevideo; the Blancos were headed by the second President Manuel Oribe, who looked after the agricultural interests of the countryside and promoted protectionism.

Both parties took their informal names from the color of the armbands that their supporters wore. Initially, the Colorados wore blue, but, when it faded in the sun, they replaced it with red. The parties became associated with warring political factions in neighboring Argentina. The Colorados favored the exiled Argentinian liberal Unitarios, many of whom had taken refuge in Montevideo, while the Blanco president Manuel Oribe was a close friend of the Argentine ruler Juan Manuel de Rosas.

Oribe took Rosas's side when the French navy blockaded Buenos Aires in 1838. This led the Colorados and the exiled Unitarios to seek French backing against Oribe, and, on 15 June 1838, an army, led by the Colorado leader Rivera, overthrew Oribe who fled to Argentina. The Argentinian Unitarios then formed a government-in-exile in Montevideo, and, with secret French encouragement, Rivera declared war on Rosas in 1839. The conflict would last 13 years and become known as the Guerra Grande (the Great War).

In 1840, an army of exiled Unitarios attempted to invade northern Argentina from Uruguay but had little success. In 1842, the Argentinian army overran Uruguay on Oribe's behalf. They seized most of the country but failed to take the capital. The Great Siege of Montevideo, which began in February 1843, lasted nine years. The besieged Uruguayans called on resident foreigners for help. French and Italian legions were formed. The latter was led by the exiled Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was working as a mathematics teacher in Montevideo when the war broke out. Garibaldi was also made head of the Uruguayan navy.

During this siege, Uruguay had two parallel governments:

- Gobierno de la Defensa in Montevideo, led by Joaquín Suárez (1843–1852).

- Gobierno del Cerrito (with headquarters at Cerrito de la Victoria neighborhood), ruling the rest of the country, led by Manuel Oribe (1843–1851).

The Argentinian blockade of Montevideo was ineffective as Rosas generally tried not to interfere with international shipping on the River Plate, but, in 1845, when access to Paraguay was blocked, Great Britain and France allied against Rosas, seized his fleet, and began a blockade of Buenos Aires, while Brazil joined in the war against Argentina. Rosas reached peace deals with Great Britain and France in 1849 and 1850, respectively. The French agreed to withdraw their legion if Rosas evacuated Argentinian troops from Uruguay. Oribe still maintained a loose siege of the capital. In 1851, the Argentinian provincial strongman Justo José de Urquiza turned against Rosas and signed a pact with the exiled Unitarios, the Uruguayan Colorados, and Brazil against him. Urquiza crossed into Uruguay, defeated Oribe, and lifted the siege of Montevideo. He then overthrew Rosas at the Battle of Caseros on 3 February 1852. With Rosas's defeat and exile, the "Guerra Grande" finally came to an end. Slavery was officially abolished in 1852. A ruling triumvirate consisting of Rivera, Lavalleja, and Venancio Flores was established, but Lavalleja died in 1853, Rivera in 1854, and Flores was overthrown in 1855.[6]

Foreign relations

The government of Montevideo rewarded Brazil's financial and military support by signing five treaties in 1851 that provided for a perpetual alliance between the two countries. Montevideo confirmed Brazil's right to intervene in Uruguay's internal affairs. Uruguay also renounced its territorial claims north of the Río Cuareim, thereby reducing its area to about 176,000 square kilometers (68,000 sq mi) and recognized Brazil's exclusive right of navigation in the Laguna Merin and the Rio Yaguaron, the natural border between the countries.{{Handelmann, Heinrich, and Lucia Furquim Lahmeyer. Historia do Brasil / por Henrique Handelmann [traducção brasileira feita pelo Instituto historico e geographico brasileiro]. Translated by Lucia Furquim Lahmeyer. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa nacional, 1931.}}

In accordance with the 1851 treaties, Brazil intervened militarily in Uruguay as often as it deemed necessary.[7] In 1865, the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was signed by the Emperor of Brazil, the President of Argentina, and the Colorado general Venancio Flores, the Uruguayan head of government whom they had both helped to gain power. The Triple Alliance was created to wage a war against the Paraguayan leader Francisco Solano López.[7] The resulting Paraguayan War ended with the invasion of Paraguay and its defeat by the armies of the three countries. Montevideo, which was used as a supply station by the Brazilian navy, experienced a period of prosperity and relative calm during this war.[7]

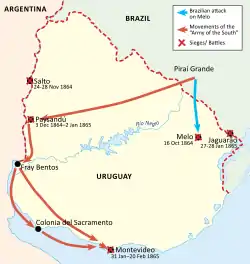

The Uruguayan War, 1864–65

The Uruguayan War was fought between the governing Blancos and an alliance of the Empire of Brazil with the Colorados who were supported by Argentina. In 1863, the Colorado leader Venancio Flores launched the Liberating Crusade aimed at toppling President Bernardo Berro and his Colorado–Blanco coalition (Fusionist) government. Flores was aided by Argentina's President Bartolomé Mitre. The Fusionist coalition collapsed as Colorados joined Flores's ranks.

The Uruguayan civil war developed into a crisis of international scope that destabilized the entire region. Even before the Colorado rebellion, the Blancos had sought an alliance with Paraguayan dictator Francisco Solano López. Berro's now purely Blanco government also received support from Argentine Federalists, who opposed Mitre and his Unitarians. The situation deteriorated as the Empire of Brazil was drawn into the conflict. Brazil decided to intervene to reestablish the security of its southern frontiers and its influence over regional affairs. In a combined offensive against Blanco strongholds, the Brazilian–Colorado troops advanced through Uruguayan territory, eventually surrounding Montevideo. Faced with certain defeat, the Blanco government capitulated on 20 February 1865.[8]

The short-lived war would have been regarded as an outstanding success for Brazilian and Argentine interests, had Paraguayan intervention in support of the Blancos (with attacks upon Brazilian and Argentine provinces) not led to the long and costly Paraguayan War. In February 1868, former Presidents Bernardo Berro and Venancio Flores were assassinated.

Social and economic developments up to 1900

.jpg.webp)

Colorado rule

The Colorados ruled without interruption from 1865 until 1958 despite internal conflicts, conflicts with neighboring states, political and economic fluctuations, and a wave of mass immigration from Europe.[9]

1872 power-sharing agreement

The government of General Lorenzo Batlle y Grau suppressed the Revolution of the Lances, which started in September 1870 under the leadership of Blanco Timoteo Aparicio.[10] After two years of struggle, a peace agreement was signed on 6 April 1872 when a power-sharing agreement was signed giving the Blancos control over four out of the thirteen departments of Uruguay—Canelones, San Jose, Florida, and Cerro Largo—and a guaranteed, if limited representation in Parliament.[10] This establishment of the policy of coparticipation represented the search for a new formula of compromise, based on the coexistence of the party in power and the party in opposition.[10]

Despite this agreement, Colorado rule was threatened by the failed Tricolor Revolution in 1875 and the Revolution of the Quebracho in 1886. The Colorado effort to reduce the Blancos to only three departments caused a Blanco uprising of 1897 that ended with the creation of 16 departments, of which the Blancos now had control over six. The Blancos were given one third of the seats in Congress.[11] This division of power lasted until President Jose Batlle y Ordonez instituted his political reforms which caused the last uprising by the Blancos in 1904 which ended with the Battle of Masoller and the death of Blanco leader Aparicio Saravia.

Military in power, 1875–1890

The power-sharing agreement of 1872 split the Colorados into two factions—the principistas, who were open to cooperation with the Blancos, and the netos, who were against it. In the 1873 Presidential election, the netos supported election of José Eugenio Ellauri, who was a surprise candidate with no political powerbase. Five days of rioting in Montevideo between the two Colorado factions led to a military coup on 15 January 1875. Ellauri was exiled and neto representative Pedro Varela assumed the Presidency.[12]

In May 1875, the principistas began the Tricolor Revolution, which was defeated later in the year by an unexpected coalition of Blanco leader Aparicio Saravia and the Army under the command of Lorenzo Latorre. Between 1875 and 1890, the military became the center of political power.[13] The Presidency was controlled by colonels Latorre, Santos and Tajes. This period lasted through the Presidencies of Pedro Varela (January 1875–March 1876), Lorenzo Latorre (March 1876–March 1880), Francisco Antonino Vidal (March 1880–March 1882), Maximo Santos (March 1882–March 1886), Francisco Antonino Vidal (March 1886–May 1886), Maximo Santos (May 1886–November 1886), and Maximo Tajes (November 1886–March 1890).

In 1876, Colonel Latorre overthrew the Varela government and established a strong executive Presidency. The economy was stabilized and exports, mainly of Hereford beef and Merino wool, increased. Fray Bentos corned beef production started. Power of regional caudillos (mostly Blancos) was reduced and a modern state apparatus established. Latorre was followed by Vidal and Santos, during whose rule rebels from Argentina invaded on 28 March 1886, but they were soon defeated by Tajes. On 17 August 1886, in a failed assassination attempt, President Santos was shot in the jaw. Faced with mounting health and economic problems, he resigned on 18 November 1886, and Tajes was then elected president.[12]

During this authoritarian period, the government took steps toward the organization of the country as a modern state, encouraging its economic and social transformation. Pressure groups (consisting mainly of businessmen, hacendados, and industrialists) were organized and had a strong influence on government.[13] In a transition period during the Tajes Presidency, politicians began recovering lost ground and some civilian participation in government occurred.[13]

Immigration

After the "Guerra Grande" there was a steady increase in the number of immigrants, which led to the creation of large Italian Uruguayan and Spanish Uruguayan communities. Within a few decades, the population of Uruguay doubled and Montevideo's tripled as most of the recent immigrants settled there. The number of immigrants rose from 48 percent of the population in 1860 to 68 percent in 1868. In the 1870s, a further 100,000 Europeans arrived, so that, by 1879, about 438,000 people were living in Uruguay, a quarter of them in Montevideo.[14] Due to immigration, Uruguay's population reached one million in the early 20th century.[15]

Economy

The economy saw a steep upswing after the "Guerra Grande", above all in livestock raising and export. Between 1860 and 1868, the number of sheep rose from 3 to 17 million. The reason for this increase lay above all in the improved methods of husbandry introduced by European immigrants.[16]

In 1857, the first bank was opened: Montevideo's Banco Comercial.[17] Three years later, a canal system was begun and the first telegraph line was set up. In 1868 rail links were built between the capital and the countryside.[18] The Italians set up the Camera di Commercio Italiana di Montevideo (Italian Chamber of Commerce of Montevideo) which played a strategic role in trade with Italy and building up the Italian middle class in the city.[19] In 1896, the state bank, Banco de la Republica, was established.[20][21]

Montevideo became a major economic center of the region. Thanks to its natural harbor, it became an entrepôt, or distribution hub, for goods from Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. The towns of Paysandú and Salto, both on the Uruguay River, also experienced similar development.[22]

Social

Despite the dictatorships and political turmoil of the 19th century, a number of positive social advances nevertheless took place. A law of 1838 required “the deduction of one day’s pay per month from the salaries of public employees in order that civil pensions and retirement allowances might be serviced.”[23] In 1896, a teachers’ pension and retirement fund was set up.[24] In terms of public health, an early action involved the establishment of a large market in Montevideo “to improve the highly unsanitary conditions under which meat and other foods had been sold.” In 1853, the Old City took steps to extend its rudimentary sewer system, and Montevideo became the first Latin American city to have a complete sewerage system. Action to provide running water started in 1866. In 1847 the legislature passed an ordinance providing for vaccination against smallpox, while vaccination (which began for schoolchildren as early as 1829) became compulsory for infants in 1850. The 1850’s also saw “the first systematic and extensive steps taken to provide quarantine and disinfection services.” In 1883 a “House of Disinfection” was established in Montevideo and 4 years later a lazaret which was considered a model of its kind was established on the Isla de Flores.[25] In 1871 and 1878 regulations were issued to “govern the construction of conventillos in terms of aeration and sanitation.”[26] In the early 1830s Uruguay’s first real hospital, the Charity Hospital, was established at Montevideo.[23] In education, Uruguay’s first school law was passed in 1826, while the first budget for public instruction “involved the munificent sum of 10,800 pesos.”[27] A project for a national university was approved in 1833, and organizations were formed in 1847 and 1848 to develop and control primary and secondary education. In 1849, the University of Montevideo (officially the University of the Republic) was established on July 18, 1849.[28] In 1878 the first law to set up a free public education system was approved.[29] In 1880 the Executive Branch was authorized to form colonies or help colonization companies, establishing the right of expropriation for reasons of public utility is established. In 1882 public lands occupied by tenants could be used for the formation of agricultural colonies.[30] A decree of November 28, 1882 provided that public lands, occupied by tenants, may be used for the formation of agricultural colonies.[31]

The second half of the 19th century would be characterized by the emergence of important innovations, both in the area of private and public care. The first mutual organizations also appeared, which were based on the prepaid and non-profit system. They would be administered cooperatively, with members electing their own authorities, which were in charge of contracting medical services for the members. In 1853 the First Spanish Association of Mutual Aid was founded, the first of its kind on the entire continent. In the following 40 years, Various institutions would be organized over the next 4 decades, based on the principles of mutualism and with diverse associative origins. The modernizing impulse also lead, as noted by one study, “the young State to begin to formally assume its responsibility in caring for the population.” In 1889, the Public Charity and Beneficence Commission was established by Law, which depended on the Ministry of Government. The task of this commission was to administer charity hospitals. The network of public establishments also started to expand, as demonstrated by the creation of the Salto Hospital in 1878, the Vilardebó Hospital in 1880, those in Colonia, Florida and Paysandú in 1896, and the Fermín Ferreira in 1891. In addition to direct care, the State assumed a greater role in regulation and sectoral stewardship. Law 2408 of 1895, for instance, established the National Hygiene Council, also dependent on the Ministry of Government, with fundamentally regulatory and control functions. Additionally, it was responsible for 18 Departmental Councils, which took the presence of the health authority to every corner of the country.. As noted by one study, “This National Hygiene Council was made up of 16 honorary members representing various State agencies. All members had a voice, but the decision-making capacity was exercised by the seven regular members, who had to be professional doctors. It is noteworthy that the Departmental Councils of the interior of the country, despite having a low degree of management autonomy, provided for the participation of residents in them.[32]

In spite of these developments, Uruguay suffered from numerous social and economic inequalities. As noted by one study, “The government had not as yet turned its attention to the relations of labour and capital: there was no regulation of the labour of women and children, no provision for accidents, no official means of protest for employees against unfair treatment, no restrictions on the hours of work.”[33] Rural workers experienced low wages and poor living conditions and were wholly dependent on the will of the landowner, and while slavery had been abolished in the forties “the rural worker was still without defences against the landowner and was a willing instrument in the hands of political leaders.”[34] As noted by another study, wire fences cut down the need for hands, with excess hands asked or forced to leave. They were dragooned into the army or drifted in rural slums known as pueblos de ratas (rat towns).[35]

Measures to mitigate the problems of Uruguayan society would be undertaken during the course of what became known as the Batlle era.

Batlle era, 1903–33

José Batlle y Ordóñez, President from 1903 to 1907 and again from 1911 to 1915, set the pattern for Uruguay's modern political development and dominated the political scene until his death in 1929. Batlle was opposed to the coparticipation agreement because he considered division of departments among the parties to be undemocratic. The Blancos feared loss of their power if a proportional election system was introduced and started their last revolt in 1904, which ended with the Colorado victory at the Battle of Masoller.[36]

After victory over the Blancos, Batlle introduced widespread political, social, and economic reforms, such as a welfare program, government participation in many facets of the economy, and a new constitution. Between 1904 and 1916, according one study, "the triumphant sector of the Colorado Party, Batllism, emphasized social programs and what the philosopher Carlos Vaz Ferreira (1915) denominated pobrismo (focus on poverty), constructing a state that was intended to be the "shield of the weak" (Perelli 1985)."[37] According to one study, Batlle ratified his war victory "with the 1905 electoral victory which put his supporters into the legislature and his lieutenants in control of the party organization all over Uruguay. Having secured his position, he was ready for reform."[38] In the legislative election that Batlle called for January 1905, his hand-picked candidates won the majority of seats. According to one study, "It was the first election in thirty years in which the outcome was not predetermined."[39] In the 1905 elections for the House of Diputados, Batlle’s sector the Batllistas won 57.7% of the vote. In subsequent elections for the House of Diputados and the Constituency Assembly the Batllistas continued to perform well, winning 64.2% of the vote in 1907, 79.9% of the vote in 1910, 60% of the vote in 1913, 45.2% of the vote in 1916, 49.3% of the vote in 1917, 29.5% of the vote in 1919, and 52.2% of the vote in 1920.[40][41] Also, in the elections of 1905, 1907 and 1913, in nineteen departments Batllismo won in seventeen.[42]According to one observer “Batllismo, from 1911 to 1915, was all-powerful, dominated absolutely in the Chamber of Deputies, it had some reservations in the Senate. There was not a single nationalist representative in the Senate at that time.”[43] As noted by one study, “Until 1917, Batllismo dominated the successive elections and obtained its best result in 1910 with 79.9 % of the votes.”[44] As noted by another study, "The institutional difficulty resulting from the complex reading of the results was apparently not immediately perceived by contemporaries, but it came to the forefront when in January 1917 the legislative elections held according to the traditional rule of public vote gave Batlle back control of both chambers."[45] One study has noted that 1917 "Batllismo had the majority in the chambers that it lacked in the Constituent Assembly."[46]

The Batlle era saw the introduction of various reforms[47][48][49][50][51] such as new rights for working people,[52] the encouragement of colonization,[53] universal male suffrage, the nationalization of foreign-owned companies, the creation of a modern social welfare system. Under Batlle, the electorate was increased from 46,000 to 188,000. Income tax for lower incomes was abolished in 1905, secondary schools were established in every city (1906), the right of divorce was given to women (1907), and the telephone network was nationalized (1915).[1] Severance pay for commercial employees was introduced in 1914, and an eight-hour working day in 1915. In 1917, Uruguay proclaimed a secular republic.[54] In 1910 a hospital for children and an asylum were constructed, while building started on a hospital for tuberculosis patients. In 1915, a Maternity House, asylums for older children, a milk program for children up the age of two, and a service in medical emergencies in homes were initiated.[55] Hospital services "also began to improve in the capital cities of the interior" while small asylums were set up for abandoned mothers and their children in some rural towns.[55] Research institutes were also founded, while a children’s hospital, an orphanage, a senior citizen’s home and military hospital were also built.[56] In 1920 a second public hospital was established in Montevideo was established to provide general services, while another facility provided exclusive care for the elderly and beggars.[55] In 1927 the minimum wage for public functionaries was introduced.[57] Various reforms in education were also carried out. Public secondary education was instituted while university education was reformed, "creating new schools for professionals." In 1912 secondary schools were set up in each of the 18 departmental capitals of the interior "and incorporated into the Secondary Education Section of the University that operated in Montevideo (Universidad de la Republica). A secondary night school was established in 1919 "so that adults who had not finished secondary school could continue their formal education."[58] The National Commission for Charity and Public Welfare was authorized to create a "Gota de Leche" clinic.[59] A period of land reform lastly roughly between 1913 and 1923, with 2 laws passed that established 10 agricultural "colonies" totalling "about 75,000 acres, divided into farms averaging about 100 acres in size."[60] Through support provided by the superior Government, Public Assistance was able to open the first Gota de Leche Clinic in the city of Montevideo at the start of 1908.[61]

Around 1900, infant mortality rates (IMR) in Uruguay were among the world's lowest, indicating a very healthy population. By 1910, however, the IMR leveled off, while it continued to drop in other countries. The leading causes of death—diarrheal and respiratory diseases—did not decline, indicating a growing public health problem.[62]

In 1930, Uruguay hosted the first FIFA World Cup. Although relatively few countries took part, the event provided national pride when the home team won the tournament over their neighbors Argentina.[63]

The reforms of the Batlle era served as a rallying cry for supporters of Batlle's ideas. In the lead up to the November 1919 general elections, the Agrupación Colorada Batllista started publishing its program of works carried out from 1903 to 1918. The points covered were ‘Pacification of the country based on respect for institutions; Abolition of the death penalty; abolition of the levy regime for the army's comeback; administrative and personal honesty; construction of bridges, roads, ports, railways; settlement of divorce; creation of departmental high schools; creation of schools and salary increase for teachers; free high school and university education; creation of the State Power Plants, the Mortgage Bank, the Insurance Bank and the State railways and trams; creation of the Agronomy and Veterinary Schools and the Agronomic Stations; organization of the Business School; construction of university buildings; creation of the Historical Museum, the Natural History Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts; creation of boulevards and public walks; initiative of the League of Nations in The Hague; organization of physical education and sports places throughout the country; establishment of old-age pensions; compensation for work accidents; regulation of women's and children's work; suspension of night work; creation of free chairs and salary increase for teachers; creation of the Institutes of Fishing, Industrial Chemistry, Geology and Drilling; suspension of discounts of 10 and 15% on the salaries of public employees; creation of the Educational Colony for Men; campaign against alcoholism; abolition of the Presidency of the Republic; establishment of the secret ballot, proportional representation and mandatory registration; departmental autonomies; separation of Church and State; vote of women and foreigners; popular insurance; legitimation of natural children; paternity investigation; fight against white slavery; establishment of the conditional sentence; establishment of broad and compulsory arbitration in international litigation; establishment of popular libraries; creation of the School of Dramatic Art and the national orchestra; creation of industrial education; creation of agricultural colonies; establishment of the agrarian pledge, rural credit and agricultural defense; creation of the Women's University; agriculture protection; stimulus laws for the improvement of livestock; foundation of hospitals in the departments; creation of the maternity, the Alienated Colony, the Gynecology Pavilion, the Children's Hospital, the Nursing School, the Vacation Colony, the Outdoor Schools and the Institutes for the deaf.’[64]

A couple of years later, the Convention of the Batllista Association 'decided to sanction a double program of principles to establish which were the previous works of the party, that should be maintained, and, at the same time, specify the aspirations or future achievements.' The works carried out as listed were '1. Democratic-representative institutions. 2. of the Collegiate Government form 3. of Municipal autonomy. 4. General and compulsory arbitration in international matters. 5. Of the separation of the State and the Church. 6. Secret ballot and proportional representation. 7. The abolition, without exception, of the death penalty. 8. On the conviction and parole of criminals. 9. Divorce at the will of the woman, without the need to express cause. 10. From the investigation of paternity. 11. Of the rights of natural children. 12. Of the secularism of teaching. 13. Free primary, secondary, preparatory and higher education. 14. From the absenteeism tax. 15. From the University of Women. 16. From departmental high schools. 17. Of night teaching. 18. Of the agronomic stations. 19. Of the free chairs and progressive salaries to the professors. 20. From the Physical Education Commission. 21. Of the right to assistance. 22. From lay public assistance. 23. The right to livelihood. 24. Of the repression of alcoholism. 25. Of the maximum day of eight hours. 26. From pensions to old age. 27. One day's rest after every five days of work. 28. Compensation for work accidents. 29. From the State Insurance Bank. 30. Of the Bank of the Republic exclusively of the State. 31. Of the nationalization of the Mortgage Bank. 32. Of the nationalization of the Power Plants. 33. Of the nationalization of the telegraphs. 34. Of the nationalization of the services of the Port. 35. Of the nationalization of the Northern Tramway and Railway, the Trinidad al Durazno Railway and the Olmos Junction at Maldonado. 36. Of the construction of the country's railways by the State and for the State. 37. The suppression of bullfights, their parodies, non-simulated pigeon shooting, cockfights, the rat-pit and all shows in which the suffering of animals is provoked as an attraction.'[65]

The Batllistas also listed a number of works to be realised, including “48. The prohibition of work for children of both sexes under 15 years of age. 49. The reduction to four hours of the work day for young people between 15 and 18 years of age. 50. The reduction to six hours of the working day work of young people between 18 and 20 years of age and of women 51. He increased up to ten pesos in old age pensions 52. The declaration by law that the mother woman deserves well from the Republic, regardless of her marital status 53. The prohibition for women to work during the 30 days that precede childbirth and during the 30 that follow it 54. The creation of nursing homes to house and assist women in the last 30 days of pregnancy and in the 30 days following childbirth or longer if their health requires it, in which they will also be instructed in how to raise children 55. The installation of nursery rooms in establishments where women with children are employed 56. The allowance of $10 per month for one year counted from the month prior to the childbirth to women who support the child even when they have salary or salary, allocation that will be provided from old age pension funds. 57. The increase in the number of asylums or maternity homes until the popular need is fully satisfied in these establishments 58. The fixing of a minimum wage for community workers, based on the main living conditions, among which must be counted in the first place healthy and sufficient food and hygienic housing and arrangement. 59. The fixing of the minimum wage of $30 for farmhands, huts or dairy, 60. The determination of the food that should be given to farmhands, huts or dairy, which must be healthy and sufficient. 61. Rest in shifts of a full day after every five days of work for ranch, cabin or dairy laborers 62. The participation of workers and employees of state companies in their profits and the increase in salaries and wages. 62. The creation of a mandatory minimum insurance of 2/^ of the wage or salary, against unemployment, illness or disability. 64. The creation of retirement and pensions for all those who work on their own account, individuals or the State. 65. The recognition of the right of retirees or pensioners to reside in the country or abroad, and to marry without losing their pension. 66. The establishment in each judicial section of a doctor, at least, designated annually by popular election of the corresponding section, with a monthly salary of not less than $200 to provide assistance to the workers and in general to any person of modest economic situation, according to a reduced rate that will be set by the municipal authorities. 67. The rigorous application of labor, protection and salary laws to the work regime of convents, asylums, congregations and religious associations.”[65]

Several of these reforms would be realized both during and after Batlle’s lifetime.

The coup of 1933

Batlle's split executive model lasted until 1933, when, during the economic crisis of the Great Depression, President Gabriel Terra assumed dictatorial powers.[11]

The new welfare state was hit hard by the Great Depression, which also caused a growing political crisis. Terra blamed the ineffective collective leadership model and, after securing agreement from the Blanco leader Luis Alberto de Herrera in March 1933, suspended the Congress, abolished the collective executive, established a dictatorial regime, and introduced a new constitution in 1934. The former President Brum committed suicide in protest against the coup.[66] In 1938, Terra was succeeded by his close political follower and brother-in-law General Alfredo Baldomir. During this time, state retained large control over nation's economy and commerce, while pursuing free-market policies. After the new Constitution of 1942 was introduced, political freedoms were restored.[67]

Post-Batlle reforms

Further reforms were carried out in the years following Batlle’s passing.[68] [69] Under a law of 25 June 1930, a minimum wage previously established on 18 November 1926 for port workers was extended "to include employees of frigoríficos who load and unload ships."[70] Accident compensation legislation was extended to cover persons employed on field work,[71] while an Act of 22 June 1931 "prescribes Sunday closing for chemists' shops, with the exception of those opening on special duty from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Provision is also made for night work." In addition, an Act of 22 October 1931 "provides for an uninterrupted weekly rest of 36 hours from 12.30 p.m. on Saturdays in all commercial establishments except those enumerated in the Act."[72] Under a Decree of 13 April 1934 aimed at establishing "uniform shop-closing hours, which was supplemented and amended by Decrees of 23 May and 4 August 1934, commercial establishments which are closed on Saturday afternoons and which can interrupt their operations at fixed hours without prejudice to the public must close at 7 p.m. Hairdressing establishments must close a t9 p.m. as a rule, and at midnight on Saturdays. These provisions apply to trading in streets and other public places. By agreement between employers and employees establishments may close earlier. Undertakings which do not fulfil the conditions mentioned above are excepted from these provisions, but during the hours when shops covered by the Decrees are closed they may not sell any goods also sold by such shops. The goods in question must be specified on a notice posted in the shop window and inside the shop." On 12 January 1934, the Minister of Public Health was empowered (12 January 1934) to issue regulations governing conditions of work in industrial establishments, while a Decree of 17 February 1934 gave effect "to Public Health Regulations entrusting the Health Inspectorate with factory inspection, etc." On 24 July 1933, a Decree concerning safety in autogenous and electric welding processes for the repair of steam generating plant was promulgated. A Decree of the 5th November1934 "made it compulsory to fit guards to machines for the preparation of macaroni and similar products." A Children's Code provided, among other things, "for a minimum age of 14 years for admission to employment, with some exceptions for school attendance, and for the enforcement of the school attendance provisions." Rules were also laid down "for the organisation of hostels for mothers with young children, working mothers' canteens, day nurseries, etc." Under Administrative Regulations of 24 May 1934, "issued under the Pensions Act, which deal with the superannuation and pension system for persons employed in commerce, industry and public utility undertakings, brings mothers with dependent children under 14 within the scope of the pension scheme, although the amount of the pension has not yet been fixed." An Act of 11 January 1934 "provides that the Ministry of Labour shall establish in the principal town in each department an employment exchange under the Pension Fund for Industry, Commerce and the Public Services."[73]

A Decree of 15 December 1936 regulated "the hours of work of persons employed in places of entertainment open at night" while the Weekly Rest Act of 23 November 1936 provided "that throughout the country shops must be shut on Sunday." To supervise enforcement of the legislation relating to holidays, a Decree of 17 February 1936 "provides that every employer must draw up at the beginning of each year a special table in triplicate, showing the dates on which the members of his staff are to go on holiday. A copy must be sent to the National Labour Institute." Also, on 26 June 1935, the provision of seats was prescribed, which was among positive measures protecting the health of women workers.[74] A Presidential Resolution of 24 February 1938 contained "industrial hygiene regulations covering such matters as medical service in the factory, first-aid, dormitories, canteens, etc." Regulations respecting safety in the construction of scaffolding were amended by a Decree of 7 September 1939, while a Decree was issued "authorising the national board for fuel, alcohol and Portland cement (Administración Nacional de Combustibles, Alcohol y Portland) to include 27,500 pesos in its budget for the payment of family allowances to its manual and non-manual employees from 1 July 1938." Also, a Decree of 19 October 1938 "laid down, for the purposes of the application of labour legislation, a legal definition which finds its main criterion in the preponderance of intellectual or physical effort expended by the wage earner." An Act of 19 November 1937 established the National Institute for Economic Housing, "whose duties are to build houses and provide public services for workers and to encourage privatebuilding." The institution of the family homestead was also introduced by an Act of May 1938.[75]

In March 1939, health registers for workers were introduced, along with periodical medical examination in unhealthy trades, while a Decree of August 1939 "makes it compulsory for employers to provide special protective clothing for workers working in water." A long schedule of diseases was also adopted by a Decree of August 1939 which covered silicosis, among other diseases. A resolution of January 1939 "made provision for instruction in industrial and social hygiene and the training of health visitors." In addition, a Decree of 3 November 1939 dealt with safety in the use of grape pressing machines, and an Act of 22 December 1939 "amended the Act of :23 January 1934 concerning home work and was intended, among other matters, to enable the Minimum Wage-Fixing Machinery Convention, 1928 (No. 26), to be applied. The Act covers home workers of both sexes engaged in manual work for industrial or commercial establishments."[76] A law of December 20 1939 Law No. 9898 (Land for Farmers): authorized an expropriation in favor of evicted farmers, while Law No. 10,051 (on land division) of 1941 established “a regime for expropriation, exploitation, etc., with the intervention of the BHU.” [77]

A Decree of 15 March 1947 "provides for Government intervention in the settlement of collective industrial disputes by means of conciliation boards." Act No. 10,910 of 4 June 1947 "provides for the establishment of other special boards to deal with transfers of salaried or wage-earning employees of public-utility and analogous undertakings; these are composed of three magistrates or exmagistrates, one to be appointed by the employees, one by the undertaking and the third by agreement between the two sides. In case of failure duly to appoint any member of the board, the appointment is made by the President of the Supreme Court of Justice. This Act does not cover employees with less than ten years' service or those whose work necessarily involves frequent transfer from one place to another." Act, No. 10,913 of 25 June 1947 "provides for the establishment of a joint committee, a conciliation board and a court of arbitration in each undertaking holding a concession for a public service. The joint committee is composed of not more than three representatives of the .undertaking and an equal number of delegates of the personnel, the latter being elected by secret ballot under the supervision of the electoral authority. The committees deal with dismissals, transfers, suspensions, disciplinary action and other causes of difference, as well as with questions relating to the organisation of work and to industrial hygiene and safety."[78]

A statute of 1930 permitted teachers who had worked for 10 years to retire they were mothers of small children. This was later extended to all female workers. In the Fifties retirement benefits "were permitted for those who had been self-employed without ever having contributed to a retirement fund."[79] In terms of housing a 1951 law sheltered the functionaries of the legislative branch. A law was passed in 1953 to meet the requirements of the banking retirement fund, which in accordance with the BHU administered funds for housing loans, and in 1954 a law was approved for members of the armed forces.[80] A National Housing Plan was also approved, with considerable housing construction in Montevideo and the coastal cities taking place between 1970 and 1972.[81] A law of December 1968, known as the 1968 National Housing Law, also greatly increased the number of housing cooperatives and "specified a detailed regulatory framework for housing cooperatives."[82][83]

In 1967 a new constitution was approved which instituted 9 years of mandatory education.[84] Private training colleges that had been established in almost all towns in the interior on the initiative of the teachers' and parents' associations received a government grant in 1949[85] The number of school canteens and school milk services increased, as well as the school psychology services. New classes for handicapped children were also opened.[86] In terms of secondary education, a law of 31 January 1957 "made official seven inland lycées, set up an experimental evening school inland and a day lycée and an evening lycée in the capita." In addition, a law of 29 November 1957 "increased by 9 million the 18 million pesos allocated by the 1950 law for the purchase of land the construction of new buildings for lycées and the adaptation and enlargement of existing schools."[87]

In 1934, a program of establishing low-cost restaurants where well-balanced meals could be served to workers at minimum prices was started. Such as restaurants in 1937-38 served "within a single year more than 1,500,000 meals in Montevideo and more than 2,000,000 in other parts of Uruguay." Paid industrial work done in homes was regulated and restricted by laws of 1934 and 1940, while a 1940 law fixed minimum standards for work on rice plantations. Under an Act of 1944 "certain other kinds of rural workers were extended benefits previously granted urban employees." In addition, an Agricultural Workers’ Code, which was enacted in October 1946, south to provide "general coverage to rural workers on such matters as wages, housing, weekly rest and annual holidays, unfair dismissal, etc." Wage councils were set up by a law of November 1943, while systematic legislation for dealing with compensation for dismissal was adopted in 1944.[88] The coverage of family allowances and unemployment subsidies was also extended,[89] while a number of other labor laws were carried out, concerning such matters as vacations, working hours and health insurance.[90]

World War II

Admiral Graf Spee

On 13 December 1939, the Battle of the River Plate was fought a day's sailing northeast of Uruguay between three British cruisers and the German "pocket battleship" Admiral Graf Spee. After a three-day layover in the port of Montevideo, the captain of Admiral Graf Spee, believing he was hopelessly outnumbered, ordered the ship scuttled on 17 December. Most of the surviving crew of 1,150 were interned in Uruguay and Argentina and many remained after the war. A German Embassy official in Uruguay has said that his government sent an official letter claiming ownership of the vessel. Any German claim would be invalid because, early in 1940, the Nazi government sold salvaging rights of the vessel to a Uruguayan businessman who was acting on behalf of the British government, and any salvaging rights would have expired under Uruguayan law.[91]

In June 1940, Germany threatened to break off diplomatic relations with Uruguay.[92] In December, Germany protested that Uruguay gave safe harbor to HMS Carnarvon Castle after she fought the German raider Thor.[93] The ship was repaired with steel plate reportedly salvaged from Admiral Graf Spee.[94]

International relations

On 25 January 1942, Uruguay terminated its diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany, as did 21 other Latin American nations (Argentina did not).[95] In February 1945, Uruguay signed the Declaration by United Nations and subsequently declared war on the Axis powers but did not participate in any actual fighting.[96]

Collapse of the Uruguayan miracle

Uruguay reached the peak of its economic prosperity thanks to the Second World War and the Korean War, when it reached the highest per capita income in Latin America. The country supplied beef, wool, and leather to the Allied armies. In 1946, a Batlle loyalist, Tomás Berreta, was elected to Presidency, and, after his sudden death, Batlle's nephew, Luis Batlle Berres, became the President. In 1949, to cover the British debt for the beef deliveries during WWII, British owned railroads and water companies were nationalized. The 1951 constitutional referendum created the Constitution of 1952 which returned to the collective executive model and the National Council of Government was created.

The end of the large global military conflicts by mid-1980s caused troubles for the country. Because of a decrease in demand in the world market for agricultural products, Uruguay began having economic problems, which included inflation, mass unemployment, and a steep drop in the standard of living for the workers. This led to student militancy and labor unrest. The collective ruling council was unable to agree on harsh measures that were required to stabilize the economy. As the demand for Uruguay's export products plummeted, the collective leadership tried to avoid budget cuts by spending Uruguay's currency reserves and then began taking foreign loans. The Uruguayan peso was devalued, inflation reached 60%, and the economy was in deep crisis.

The Blancos won the 1958 elections and became the ruling party in the Council. They struggled to improve the economy and advocated a return to strong Presidency. After a constitutional referendum, the Council was replaced by a single Presidency under the new Constitution of 1967. The elections of 1967 returned the Colorados to power, and they became increasingly repressive in the face of growing popular protests and Tupamaros insurgency.

The Tupamaros were an urban guerrilla movement formed in the early 1960s. They began by robbing banks and distributing food and money in poor neighborhoods, then undertaking political kidnappings and attacks on security forces. They occupied a city near Montevideo in an operation known as the Taking of Pando. Their efforts succeeded in first embarrassing, and then destabilizing, the government. The US Office of Public Safety (OPS) began operating in Uruguay in 1965. The US OPS trained Uruguayan police and intelligence in policing and interrogation techniques. The Uruguayan Chief of Police Intelligence, Alejandro Otero, told a Brazilian newspaper in 1970 that the OPS, especially the head of the OPS in Uruguay, Dan Mitrione, had instructed the Uruguayan police how to torture suspects, especially with electrical implements.

Military dictatorship, 1973–1985

President Jorge Pacheco declared a state of emergency in 1968, and this was followed by a further suspension of civil liberties in 1972 by his successor, President Juan María Bordaberry. President Bordaberry brought the Army in to combat the guerrillas of the Tupamaros Movement of National Liberation (MLN), which was led by Raúl Sendic. After defeating the Tupamaros, the military seized power in 1973. Torture was effectively used to gather information needed to break up the MLN and also against trade union officers, members of the Communist Party and even regular citizens. Torture practices extended until the end of Uruguayan dictatorship in 1985. Uruguay soon had the highest per capita percentage of political prisoners in the world. The MLN heads were isolated in improvised prisons and subjected to repeated acts of torture. Emigration from Uruguay rose drastically as large numbers of Uruguayans looked for political asylum throughout the world.

Bordaberry was finally removed from his "president charge" in 1976. He was first succeeded by Alberto Demicheli. Subsequently, a national council chosen by the military government elected Aparicio Méndez. In 1980, in order to legitimize their position, the armed forces proposed a change in the constitution, to be subjected to a popular vote by a referendum. The "No" votes against the constitutional changes totaled 57.2 percent of the turnout, showing the unpopularity of the de facto government that was later accelerated by an economic crisis.

In 1981, General Gregorio Álvarez assumed the presidency. Massive protests against the dictatorship broke out in 1984. After a 24-hour general strike, talks began, and the armed forces announced a plan for return to civilian rule. National elections were held later in 1984. Colorado Party leader Julio María Sanguinetti won the presidency and, following the brief interim Presidency of Rafael Addiego Bruno, served from 1985 to 1990. The first Sanguinetti administration implemented economic reforms and consolidated democratization following the country's years under military rule. Nonetheless, Sanguinetti never supported the human rights violations accusations, and his government did not prosecute the military officials who engaged in repression and torture against either the Tupamaros or the MLN. Instead, he opted for signing an amnesty treaty called in Spanish "Ley de Amnistia".

Around 180 Uruguayans are known to have been killed during the 12-year military rule from 1973 to 1985.[97] Most were killed in Argentina and other neighboring countries, with only 36 of them having been killed in Uruguay.[98] A large number of those killed were never found, and the missing people have been referred to as the "disappeared", or "desaparecidos" in Spanish.

Recent history

Sanguinetti's economic reforms, focusing on the attraction of foreign trade and capital, achieved some success and stabilized the economy. In order to promote national reconciliation and facilitate the return of democratic civilian rule, Sanguinetti secured public approval by plebiscite of a controversial general amnesty for military leaders accused of committing human rights violations under the military regime and sped the release of former guerrillas.

The National Party's Luis Alberto Lacalle won the 1989 presidential election and served from 1990 to 1995. President Lacalle executed major economic structural reforms and pursued further liberalization of trade regimes, including Uruguay's inclusion in the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) in 1991. Despite economic growth during Lacalle's term, adjustment and privatization efforts provoked political opposition, and some reforms were overturned by referendum.

In the 1994 elections, former President Sanguinetti won a new term, which ran from 1995 until March 2000. As no single party had a majority in the General Assembly, the National Party joined with Sanguinetti's Colorado Party in a coalition government. The Sanguinetti government continued Uruguay's economic reforms and integration into MERCOSUR. Other important reforms were aimed at improving the electoral system, social security, education, and public safety. The economy grew steadily for most of Sanguinetti's term until low commodity prices and economic difficulties in its main export markets caused a recession in 1999, which continued into 2002.

The 1999 national elections were held under a new electoral system established by a 1996 constitutional amendment. Primaries in April decided single presidential candidates for each party, and national elections on 31 October determined representation in the legislature. As no presidential candidate received a majority in the October election, a runoff was held in November. In the runoff, Colorado Party candidate Jorge Batlle, aided by the support of the National Party, defeated Broad Front candidate Tabaré Vázquez.[99]

The Colorado and National Parties continued their legislative coalition, as neither party by itself won as many seats as the 40 percent of each house won by the Broad Front coalition. The formal coalition ended in November 2002, when the Blancos withdrew their ministers from the cabinet, although the Blancos continued to support the Colorados on most issues.

Batlle's five-year term was marked by economic recession and uncertainty, first with the 1999 devaluation of the Brazilian real, then with the outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease (aftosa) in Uruguay's key beef sector in 2001, and finally with the political and economic collapse of Argentina. Unemployment rose to close to 20 percent, real wages fell, the peso was devalued, and the percentage of Uruguayans in poverty reached almost 40 percent.

These worsening economic conditions played a part in turning public opinion against the free market economic policies adopted by the Batlle administration and its predecessors, leading to popular rejection through plebiscites of proposals for privatization of the state petroleum company in 2003 and of the state water company in 2004.

In 1989, elections were held in Montevideo which saw the candidate of the Broad Front, Tabaré Vázquez, elected mayor of Montevideo. Vasquez would go on to hold the post of mayor from 1990 to 1994. The victory of the Broad Front was arguably the result of long-standing social problems, with one observer noting "The combination of economic crisis, military dictatorship and neoliberal policies had led to a drop in living standards and social equality as well as a decrease in social spending and urban services. The social safety net that had once made Uruguay a model welfare state was badly frayed, and government, from garbage collection to mass transport, no longer worked well. Added to these traumas was the trial of dealing with a municipal bureaucracy notorious for its arrogance and inefficiency. Paying one’s taxes or filling out a forin could take hours; securing services from the centralized municipal government could take years." The Frente Amplio promised to tackle these problems, creating a municipal government that was efficient, efficacious and responsive, services that were modern and affordable, and a city whose financial burdens and economic benefits were more equitably distributed. The political subtext was clear. If the Frente Amplio could turn Montevideo around in so dramatic a fashion, it would be in a position to mount a serious challenge for national power, and Vázquez would become a credible presidential candidate.” During the time the Broad Front governed Montevideo, a range of social initiatives were carried out. New street lights were installed, while housing construction was promoted by giving municipal lands to communities “for cooperative self-built residential housing, and by funding the rental of construction machinery and contributing materials at low prices which are repaid through long-term loans from the public Banco Hipotecario or foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs).” More land titles were given to squatters than any previous administration, and a construction-materials “bank” was established to help people improve their housing. Public-vaccination plans were also expanded and an eye-care and clinic plan was initiated, though not fully implemented, while distribution of subsidized milk was tripled and free milk provided for institutional daytime snacks. In addition, the burden of subsidizing students and the elderly from other bus riders through higher fares was shifted to the municipality through direct subsidies to the bus companies.[100]

In 2004, Uruguayans elected Tabaré Vázquez as president, while giving the Broad Front coalition a majority in both houses of parliament.[101] The newly elected government, while pledging to continue payments on Uruguay's external debt, also promised to undertake a crash jobs programs to attack the widespread problems of poverty and unemployment.

In 2009, former Tupamaro and agriculture minister, José Mujica, was elected president, subsequently succeeding Vázquez on 1 March 2010.[102] Abortion was legalized in 2012,[103] followed by same-sex marriage[104] and cannabis in the following year.[105] A number of other reforms were carried out during the Broad Front's time in office in areas like social security, [106] taxation,[107] education,[108] housing,[109] tobacco control, [110] and worker's rights.[111]

The number of trade union activists has quadrupled since 2003, from 110,000 to over 400,000 in 2015 for a working population of 1.5 million people. According to the International Trade Union Confederation, Uruguay has become the most advanced country in the Americas in terms of respect for "fundamental labour rights, in particular freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining and the right to strike".

In November 2014, former president Tabaré Vázquez defeated center-right opposition candidate Luis Lacalle Pou in the presidential election.[112] On 1 March 2015, Tabare Vazquez was sworn in as the new President of Uruguay to succeed president José Mujica.[113]

In November 2019, conservative Luis Lacalle Pou won the election, bringing the end to 15 years of leftist rule of Broad Front. On 1 March 2020, Luis Lacalle Pou, the son of former president Luis Alberto Lacalle, was sworn in as the new President of Uruguay.[114][115]

See also

References

- Jermyn, pp. 17–31.

- Bethell, Leslie (1984). The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume 1, Colonial Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 257.

- Ciferri, Alberto (2019). An Overview of Historical and Socio-economic Evolution in the Americas. United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 978-1-5275-3513-8.

- Kaufman, Will; Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl (1 March 2005). Britain and the Americas [3 volumes]: Culture, Politics, and History [3 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 833. ISBN 978-1-85109-436-3.

- Burford, p. 17.

- Burford, p. 18.

- Rex A. Hudson; Sandra W. Meditz, eds. (1990). "The Struggle for Survival, 1852–1875 (Chapter 7)". Uruguay: A Country Study. Washington DC: Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Caudillos and Political Stability". Country Studies US. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- The New York Times. (2004, July 15). Uruguay. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/15/travel/uruguay.html .

- Rex A. Hudson; Sandra W. Meditz, eds. (1990). "Caudillos and Political Stability (Chapter 9)". Uruguay: A Country Study. Washington DC: Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- Lewis, Paul H. (2005). Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America: Dictators, Despots, and Tyrants. London: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 84–87. ISBN 978-07425-37392.

- Scheina, ch. 25.

- Rex A. Hudson; Sandra W. Meditz, eds. (1990). "Modern Uruguay, 1875–1903 (Chapter 10)". Uruguay: A Country Study. Washington DC: Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- Goebel, pp. 191–229.

- Hudson, Rex (1992). Uruguay: A Country Study. Washington D.C: Federal Research Division. pp. 65. ISBN 0844407372.

- Johan Martin Gerard Kleinpenning, Peopling the Purple Land: A Historical Geography of Rural Uruguay, 1500-1915 (Amsterdam: Centrum voor Studie en Documentatie van Latijns Amerika, 1965/1995) https://books.google.com/books?id=Yf4DAQAAIAAJ

- New York's International Banking Directory (1922), 872; available at https://books.google.com/books?id=1s8oAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA872

- "Trains of Uruguay - Railway Wonders of the World". www.railwaywondersoftheworld.com. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- See A. Beretta Curi (2002), La Camera di Commercio Italiana di Montevideo 1883–1933. Montevideo: Camera de Commercio Italiana. Some translated to English (2009) as essay, The contribution of Italian emigration to the formation of urban entrepreneurship in Uruguay: The creation of the Camera di Commercio Italiana di Montevideo, 1883-1933; available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298654806_The_contribution_of_Italian_emigration_to_the_formation_of_urban_entrepreneurship_in_Uruguay_The_creation_of_the_Camera_di_Commercio_Italiana_di_Montevideo_1883-1933

- Banco de la República Oriental del Uruguay, Sinopsis económica y financiera del Uruguay (Montevideo: Impresara Uruguaya, 1933); and Simon G. Hanson, Utopia in Uruguay: Chapters in the Economic History of Uruguay (Oxford University Press, 1938).

- Discussed more recently in Ronn F. Pineo, Cities Of Hope: People, Protests, And Progress In Urbanizing Latin America, 1870-1930 (London: Routledge, 2018). https://books.google.com/books?id=E8mWDwAAQBAJ ISBN 9780429970191

- Raúl A. Molina (1948, 151-64) emphasizes the centrality of early-17th c. colonialist explorer Hernandarias de Saavedra in his choice of settlements, up to the present day. Discussed more recently in Gustavo Verdesio, Forgotten Conquests: Rereading New World History from the Margins (Phila. PA: Temple University Press, 2001), ch. 3, "The Pacific Penetration." https://books.google.com/books?id=tnw7GmI2ZCgC ISBN 9781566398343

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.175

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.180

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.172

- Historias de la vida privada en el Uruguay: El nacimiento de la intimidad, 1870-1920 Volume 2 1996, P.94

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.199

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.200

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.4

- Antecedentes Línea de tiempo 100 años del Reglamento de Tierras

- Instituto Nacional de Colonización. Ley No. 11.029 de 12 de enero de 1948 Informe y proyecto de ley de la Comisión Especial de Reforma Agraria del Senado y discusión parlamentaria en dicho cuerpo 1948, P.64

- La Construcción del Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud 2005-2009, P.13-14

- Utopia in Uruguay: Chapters in the Economic History of Uruguay by Simon Gabriel Hanson, Oxford University Press, 1938, P.16

- Utopia in Uruguay: Chapters in the Economic History of Uruguay by Simon Gabriel Hanson, Oxford University Press, 1938, P.8-9

- José Battle Y Ordoñez of Uruguay: the Creator of His Times, 1902-1907 by Milton I. Vanger, 1963, P.5

- Wade C. Roof, ed., Race and Residence in American Cities (Ann Arbor MI: American Academy of Political and Social Science, 1979), 145. ISBN 9780877612377

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.1

- José Battle Y Ordoñez of Uruguay: the Creator of His Times, 1902-1907 by Milton I. Vanger, 1963, P.274

- Uruguay’s José Batlle y Ordoñez: The Determined Visionary, 1915–1917 by Milton I. Vanger, P.2

- Studies in the Formation of the Nation-State in Latin America, Edited by James Dunkerley, CHAPTER 4 State Reform and Welfare in Uruguay, 1890-1930 by Fernando Lopez-Alves, P.104. As noted by the author "In Table 1 I have shown the popular vote to the Chamber of Representatives and the Constitutional Assembly, because I do not have figures showing votes for Batllismo alone – while, under the electoral system of the time, the Colorado electoral ticket included other factions as well as the Batllista group.”

- La república conservadora, 1916-1929: La "guerra de posiciones" By Gerardo Caetano , 1992, P.74

- Batlle el estado de bienestar en el Río de la Plata By Miguel J. Pujol, 1996, P.143

- Diario de sesiones de la Cámara de Senadores de la República Oriental del Uruguay Volume 259, By Uruguay, Asamblea General, Cámara de Senadores, 1967, P.333

- Batlle el estado de bienestar en el Río de la Plata By Miguel J. Pujol, 1996, P.189

- La lucha por el pasado historia y nación en Uruguay (1920-1930) By Carlos Demasi, 2004, P.26

- La lucha por el pasado historia y nación en Uruguay (1920-1930) By Carlos Demasi, 2004, P.26

- El inicio del Uruguay modern Editorial por Redacción 23 de julio de 2020 en Opinión

- El Uruguay Social por Redacción 15 de enero de 2020, en Opinión, Portada

- Bulletin of the Pan American Union October 1939, Uruguay: A Social Laboratory, P.596-608

- ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD ENTREGA No 136, EDUARDO ACEVEDO, ANALES HISTÓRICOS DEL URUGUAY TOMO VI, Abarca los gobiernos de Viera, Brum, Serrato y Campisteguy, desde 1915 hasta 1930

- Anales Issue 125 by Universidad de la República (Uruguay), 1929

- Batlle y el Batllismo by Roberto B. Giudici and Efraín González Conzi

- Antecedentes Línea de tiempo 100 años del Reglamento de Tierras

- Juan Rial, "The Social Imaginary: Utopian Political Myths in Uruguay (Change and Permanence during and after the Dictatorship)", in Saúl Sosnowski and Louise B. Popkin, eds., Repression, Exile, and Democracy: Uruguayan Culture (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 59-82. ISBN 9780822312680

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.5

- Social Security in Latin America Pressure Groups, Stratification, and Inequality By Carmelo Mesa-Lago, 1978, 3 The Case of Uruguay Prepared by Arturo C. Porzecanski, P.72-73

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.10

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.6

- El Dr. Claudio Williman, su vida pública By José Claudio Williman, 1957, P.482

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy By Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1956 P.119

- Proceedings of the Second Pan American Scientific Congress Volume 9 1917 P.242

- Birn, Anne-Emanuelle (2010). "The infant mortality conundrum in Uruguay during the first half of the twentieth century: an analysis according to causes of death". Continuity & Change. Cambridge University Press. 25 (3): 435–461. doi:10.1017/S0268416010000263. S2CID 145495121.

- Eduardo Galeano, trans. Mark Fried, Soccer in Sun and Shadow (NY: Open Road Media, 2014) ISBN 9781497639041

- ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD ENTREGA No 136, EDUARDO ACEVEDO, ANALES HISTÓRICOS DEL URUGUAY TOMO VI, Abarca los gobiernos de Viera, Brum, Serrato y Campisteguy, desde 1915 hasta 1930 P.149-151

- ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD ENTREGA No 136, EDUARDO ACEVEDO, ANALES HISTÓRICOS DEL URUGUAY TOMO VI, Abarca los gobiernos de Viera, Brum, Serrato y Campisteguy, desde 1915 hasta 1930 P.151-152

- Burford, p. 19.

- Alisky, Marvin H.; Weinstein, Martin; Vanger, Milton I.; James, Preston E. (4 October 2019). "Uruguay". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Includes details of various laws passed in Uruguay from 1935 onwards

- Includes details of social and economic developments in Uruguay from the 19th to 20th centuries

- Utopia in Uruguay: Chapters in the Economic History of Uruguay by Simon Gabriel Hanson, Oxford University Press, 1938, P.142

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1932

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1931

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1934-35

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1936-37

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1938-39

- THE I.L.O YEAR-BOOK 1939-40

- Antecedentes Línea de tiempo 100 años del Reglamento de Tierras

- Social Legislation in Uruguay by Alberto SANGUINETTI FREIRE

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.19

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.20

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.28

- Professionalization of a Social Movement: Housing Cooperatives in Uruguay, 2019

- Labor Law and Practice in Uruguay by Robert C. Hayes, 1972, P.68

- A Century of Social Welfare in Uruguay Growth to the Limit of the Batllista Social State Issue 5 By Fernando Filgueira, 1995, P.27

- International yearbook of education, v. 13, 1951

- International yearbook of education, v. 15, 1953

- yearbook of education, v.19,1957

- Uruguay: Portrait of a Democracy by Russell Humke Fitzgibbon, 1954, P.183

- Significant Social Security Legislation in Uruguay: 1829-1972

- Major Labor Laws and Decrees, January 1 1970

- Rohter, Larry (25 August 2006). "A Swastika, 60 Years Submerged, Still Inflames Debate". New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

For more than 60 years, the scuttled wreck of the Graf Spee rested undisturbed in 65 feet of murky water just outside the harbor here. But now that fragments of the vessel, once the pride of the Nazi fleet, are being recovered, a new battle has broken out over who owns those spoils and what should be done with them.

- White, John W. (20 June 1940). "Minister Ready to Ask for His Passports if Any Local Nazi Leaders Are Deported". New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

Germany has now begun to exert tremendous political and economic pressure on the Uruguayan Government to halt what Berlin calls an unfriendly anti-German campaign here. The Reich has threatened to break off diplomatic relations if any Nazi leaders are deported.

- White, John W. (10 December 1940). "Nazis Protest Aid to Raider's Victim. Object in Uruguay to Giving Carnarvon Castle 72 Hours to Mend Battle Scars". New York Times. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

The German Government, through its Minister in Montevideo, Otto Langmann, made a formal diplomatic protest this afternoon against...

- "Search For Raider". New York Times. 9 December 1940. Retrieved 22 May 2009.