Archbishop William Henry Elder

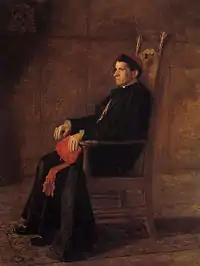

Archbishop William Henry Elder is a 1903 oil portrait by the American artist Thomas Eakins depicting the Archbishop of Cincinnati William Henry Elder, one of a series of portraits of Catholic clergy Eakins undertook late in his career. In this psychologically probing portrait, Eakins depicts the stoic Elder, frail but still imposing at 84, confronting his own mortality.

| Archbishop William Henry Elder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Thomas Eakins |

| Year | 1903 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 168.1 cm × 114.7 cm (66 3/16 in × 45 3/16 in) |

| Location | Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati |

The painting, which Eakins considered "one of my best", was awarded the Temple Gold Medal by the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Eakins famously had the medal melted down out of spite, bitter over his forced resignation from the Academy 18 years beforehand.

It is currently in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum, which purchased it in 1978.

Background

In the final decade of his active career (c. 1900–1910), Thomas Eakins painted a series of portraits of Catholic clergy. In all over a dozen clergy sat for Eakins, more than any other single profession.[1]

The series came about through Eakins's relationship with Samuel Murray, a former student and close companion. Murray was a staunch Catholic with strong ties to the Philadelphia Irish-American Catholic community. As St. Charles Borromeo Seminary was only about two miles from Eakins's home, the two chose it as a destination for their Sunday bicycle excursions, often staying for late afternoon vespers service and dinner.[2]

While the genesis of the series is clear enough, Eakins's motivations are less readily apparent. A lifelong agnostic who was outspokenly critical of Christianity in general[3] – and Catholicism in particular – Eakins debated Christ's divinity with Monsignor James P. Turner, who later sat for him,[4] and would "smile superciliously whenever someone spoke of future life."[5] Furthermore, most of these portraits were gifts, not commissions – initiated at Eakins's request and completed at his own expense.[6] These gifts were not always well received by their recipients, either: Dr. Patrick J. Garvey hid his under his bed,[7] and the portraits of Mother Mary Patricia Waldron[8] and Bishop Edmond Prendergast[9] were lost, presumed destroyed.

Kirkpatrick suggests that Eakins respected the clerics as intellectuals despite not seeing eye-to-eye with them on spiritual matters – several were accomplished scholars. Eakins may also have appreciated their lack of worldly pretense, a trait which he shared.[10] Schendler wrote that priestly vestments offered "possibilities of form and color not available to [Eakins] in the dark suits of Philadelphia businessmen."[11] Adams speculated that Eakins decided to paint clerical portraits because he was intrigued by "the sexually ambiguous quality of priestly clothes", and "the way that the clergy appeared to cross normal gender boundaries",[5] though later biographers such as Kirkpatrick have dismissed this interpretation.[6]

- Selected clerical portraits by Eakins

Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1901–02, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles

Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1901–02, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Monsignor James F. Loughlin, 1902, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton

Monsignor James F. Loughlin, 1902, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton Archbishop Diomede Falconio, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Archbishop Diomede Falconio, 1905, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Monsignor James P. Turner, c. 1906, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Monsignor James P. Turner, c. 1906, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

Subject

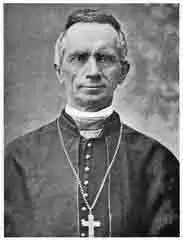

The oldest of the clerics who sat for Eakins, the 84-year-old Elder was near the end of a long and distinguished career in the church.[12] Born in Baltimore in 1819, he was ordained a priest in 1846. In 1857 he was appointed Bishop of Natchez, Mississippi.

During the Civil War he rose to prominence by refusing to follow an order given by occupying Union forces to include prayers for the President in local Catholic services – a stand for which he was briefly jailed. He further distinguished himself during a yellow fever epidemic in 1878, when he caught the disease while ministering to the sick.[12]

In 1883 Elder succeeded John Baptist Purcell as the Archbishop of Cincinnati. A capable administrator, Elder soon reorganized the diocese administration and brought it out of debt.[13]

In 1903 Bishop Henry K. Moeller, Elder's secretary and future successor, heard of Eakins's clerical portraits from Henry Turner,[9] a colleague at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, and decided to commission a portrait in honor of his superior.[14] Having accepted the commission, Eakins departed Philadelphia for Cincinnati by train on November 25, 1903; Moeller paid his travel expenses.[9][13]

This was the farthest that Eakins travelled to paint a portrait; most of his subjects were local to Philadelphia. It was also unusual among his clerical portraits in that it was a commission from a stranger, rather than a gift for someone he had come to know personally. Eakins worked quickly – on December 15 he wrote to his friend and former student Frank W. Stokes that he'd finished Elder's portrait in one week.[12] "I think it one of my best," he added.[13]

Analysis

The resulting portrait, executed in oil on a 168.1 cm × 114.7 cm canvas,[15] is "a stunning painting, but not because it flatters the Archbishop."[16]

Elder is depicted seated in a frontal pose, wearing a black cassock with a violet sash and biretta.[12] The wood–paneled room behind him is left indistinct, and his vestments are depicted in little detail, putting the emphasis on Elder's gnarled hands and weathered features.

Here, as elsewhere in his work, Eakins "did not hesitate to show a sitter as frankly old."[17] Themes of aging and mortality were "as characteristic of [Eakins's] portraiture as costumes and setting were of the portraiture of his contemporaries."[18] Indeed, these themes were so central to Eakins's conception of portraiture as an art form that he once asked a sitter if he could portray him as older than he truly was, writing that he wished "to do a fine piece of work as a work of art and not a likeness."[17]

It is unsurprising then that these themes come to the forefront in his portrait of Elder, the oldest of Eakins's clerical subjects. While Eakins did not exaggerate his sitter's age in this case, he uses that heavy emphasis on an Elder's aged features as a way of exploring his psychology, rather than the objective reality of his appearance.[19] "Archbishop Elder's seeming awareness of his own mortality is one of the painting's strongest notes," Schendler writes, "The meditative quality of the portrait is associated with the impression of physical frailty."[20]

Both in its composition and in its psychologically penetrating depiction of an aging but still imposing cleric, the portrait of Elder is comparable to Velázquez's Portrait of Innocent X.[19] In sum, it is considered a "magnificent, emotionally captivating"[13] portrayal of "an extraordinary man facing inexorable time."[20]

Reception and provenance

Within two weeks of the portrait's completion, director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts Harrison Morris solicited it for their annual exhibition.[12] There it won top honors and was awarded the Temple Gold Medal. Critics acclaimed it as "quite extraordinary in its cold, deliberate analysis of a human personality," and the awards committee wrote that "...it may be doubted that [this award] has ever been given for a more solid and substantial piece of painting."[21]

Despite the academy's acclaim, Eakins was still bitter over having been forced to resign from the Academy 18 years prior. A controversial teacher, Eakins had incited the ire of the school administration by breaking various Academy policies, such as having students pose in the nude for himself and each other.[22][23][24] This came to a head when he was formally reprimanded for removing a loincloth from a male model in front of female students.[25] Further accusations of sexual impropriety – such as a private demonstration of "pelvic motions" to Amelia Van Buren[26] – soon surfaced against Eakins, and chairman of instruction Edward Coates asked for and received his resignation.[27][25]

In what would become a famous incident, Eakins appeared at the formal award ceremony in his bicycling outfit – a raggedy sweater and short trousers. He was heard to tell Coates, who had since risen to the rank of academy president, "I think you've got a heap of impudence to give me a medal."[21] After receiving his award he immediately left by bicycle for the Philadelphia Mint, where he had the gold medal melted down for cash value.[21][16] Returning home, he laid the $73 he had received from the mint on the table in front of his wife Susan Eakins, proclaiming "Sue, here's my Temple Gold Medal."[28]

In early 1904, the portrait was presented to Elder after being shown at the academy.[12] It received a more mixed reception there, as Bishop Moeller reported in a letter to Eakins: "...some who have seen the picture do not like the Archbishop's expression, but that was not your fault. You gave the Archbishop the expression he had while you were doing the work."[29]

Elder died in October 1904, and after his death the portrait remained the property of the Archdiocese, passing down from one Archbishop of Cincinnati to the next.[12] In 1978 it was purchased by the Cincinnati Art Museum, where it remains in 2023.[15]

See also

Citations

- McFeely 179

- Adams 374

- Adams 375

- Kirkpatrick 472

- Adams 376

- Kirkpatrick 470

- Kirkpatrick 473

- Kirkpatrick 474

- Kirkpatrick 475

- Kirkpatrick 471

- Schendler 197

- Goodrich 191

- Kirkpatrick 476

- Amnéus et al. 133

- Archbishop William Henry Elder in the online catalog of the Cincinnati Art Museum. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- Johns 148

- Johns 163

- Johns 165

- Sewell 105

- Schendler 208

- Kirkpatrick 477

- Kirkpatrick 300

- Kirkpatrick 311

- Kirkpatrick 321

- Kirkpatrick 313

- Kirkpatrick 323

- Adams 60

- Goodrich 201

- Adams 409

References

- Adams, Henry (2005). Eakins Revealed: the secret life of an American artist. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195156684.

- Amnéus, Cynthia; Forth, Ron; Hisey, Scott; et al. (2008). Cincinnati Art Museum: Collection Highlights. London: Giles. ISBN 9781904832539.

- Berger, Martin A. (2000). Man Made: Thomas Eakins and the construction of Gilded Age manhood. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520222091.

- Goodrich, Lloyd (1982). Thomas Eakins. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674884906.

- Johns, Elizabeth (1991). Thomas Eakins: The Heroism of Modern Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691002886.

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney (2006). The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300108559.

- McFeely, William S. (2007). Portrait: The life of Thomas Eakins. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393050653.

- Schendler, Sylvan (1967). Eakins. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 247937283.

- Sewell, Darrel (1982). Thomas Eakins: Artist of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art. ISBN 0876330472.

External links

- Archbishop William Henry Elder in the online catalog of the Cincinnati Art Museum

- Archbishop William Henry Elder in the National Portrait Gallery's Catalog of American Portraits

- Archbishop William Henry Elder on Google Arts and Culture