Grey Owl

Archibald Stansfeld Belaney (English: /ˈstænsfiːld/; September 18, 1888 – April 13, 1938), commonly known as Grey Owl, was a popular writer, public speaker and conservationist. Born an Englishman, in the latter years of his life he passed as half Indian, claiming he was the son of a Scottish man and an Apache woman.[lower-alpha 1] With books, articles and public appearances promoting wilderness conservation, he achieved fame in the 1930s. Shortly after his death in 1938, his real identity as the Englishman Archie Belaney was exposed.[2]: 210ff

Grey Owl | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Yousuf Karsh, 1936 | |

| Born | Archibald Stansfeld Belaney September 18, 1888 Hastings, East Sussex, England |

| Died | April 13, 1938 (aged 49) Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Education | Hastings Grammar School |

| Occupation(s) | Environmentalist, fur trapper |

| Employers | Dominion Parks Service |

| Known for | Environmental conservation |

| Spouses | Angele Egwuna (m. 1910)Constance Holmes (m. 1917)Yvonne Perrier (m. 1937) |

| Partner | Gertrude Bernard |

| Children | 4 |

Belaney rose to prominence as an author and lecturer on environmental issues. While working for the Dominion Parks Branch of Canada in the 1930s, Grey Owl was established as the "caretaker of park animals," first at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba and then at Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan.[2]: 92, 108 His views on conservation, expressed in numerous articles, books, lectures and films, reached audiences beyond the borders of Canada, bringing attention to the negative impact of exploiting nature and the urgent need for people to develop respect for the natural world.[3]

Recognition of Belaney includes biographies, academic studies, historic plaques in England, Ontario and Quebec, and a film based on his life, Grey Owl, directed by Richard Attenborough.

Early life

Archibald Stansfeld Belaney was born on September 18, 1888, in Hastings, England into an upper-middle-class English family. His father was George Belaney and his mother Katherine "Kittie" Cox. His paternal grandfather had come from Scotland and married in England.[2]: 8–11

Kittie was George Belaney's second wife. Before Archie's birth, George had immigrated to the United States with his then-wife Elizabeth Cox and her younger sister, Kittie. After Elizabeth's early death, George married 15-year old Kittie. Within the year they returned to England in time for the birth of their son Archie. George was unable to settle down to steady employment and wasted much of the family's fortune on various unsuccessful business ventures. He agreed to return permanently to the United States in exchange for a small allowance. Archie remained in England in the care of his father's mother, Juliana Belaney, and his father's two younger sisters, Janet Adelaide Belaney and Julia Caroline Belaney, whom the boy would know as Aunt Ada and Aunt Carry. It was Aunt Ada who would come to dominate Archie's early life.[2]: 11–13

Belaney attended Hastings Grammar School, where he excelled in subjects such as English, French and chemistry.[2]: 19 "He mixed little with the other students in class, or afterwards. The shy, withdrawn boy, ashamed of having been abandoned by his parents, lived largely in his own world.[2]: 15 Outside school, he spent time reading and exploring St Helen's Wood near his home.[4] He also collected snakes.[2]: 14

Belaney was known for pranks, such as using his chemistry set to make small bombs, which he called "Belaney Bombs".[2]: 21 Fascinated by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Belaney read about them and drew pictures of them in the margins of his books. He prepared maps showing the linguistic divisions in Canada and the locations of the tribes. His knowledge impressed his aunt Ada:

She was amazed at his knowledge of the detail. These names came rolling off his tongue without any hesitation. He was not interested in the romantic picture of the Indians but in their mastery over nature, how they lived and survived in such a harsh climate, how they organized their lives, married, hunted, fished, trapped for furs, helped themselves to the bounty of nature but “farmed” the game so that the numbers of animals never grew less.[1]: 37

Belaney left Hastings Grammar School and started working as a clerk in a lumber yard, where, on weekends, he and his friend George McCormick perfected knife throwing and marksmanship. He hated the job and ensured a sudden end to it by lowering a bag of fireworks down the chimney of the company's office. The resulting explosion almost destroyed the building. Although, in agreement with his aunt Ada, he was supposed to work longer in England, he was finally allowed to move to Canada,[2]: 23–24 with the understanding he would "learn to be a farmer while he was getting used to the country."[1]: 39

On March 29, 1906, Belaney boarded SS Canada for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Arriving on April 6, he went to Toronto, where, with no intention of becoming a farmer, he worked for some time in a retail shop (perhaps Eaton's).[2]: 24, 36

First years in Canada

Toronto held no appeal for Belaney, and in the summer or fall of 1906 he headed north. In an autobiographical manuscript, he later wrote about his experience as the train left the farmland of southern Ontario and entered the Canadian Shield:

Against the horizon & beyond the edge of the low range of hills that bounded a distance of full 30 miles, a heavy column of smoke rose & seemed to meet the sky where it turned & rolled off in immense billows to the south, the smoke of a forest fire. Over all shone the sun bringing into contrast the lights & shades of hill and valley. To me this was a wonderful sight; my first glimpse of the wilderness.[2]: 35

As he got off the train at Lake Timiskaming, located on the boundary between Ontario and Quebec, he encountered Bill Guppy, who later recalled "...his first meeting at the Temiskaming station with the 'decent young fellow, with such a friendly air, and so earnest about becoming a guide.' The veteran woodsman took him on, and would never forget this young Englishman who had '"individuality", a little something that made him stick out in any crowd.'"[2]: 35

Belaney spent the winter of 1906-1907 with Guppy and his brothers, getting his first lessons in trapping. In spring Belaney and the Guppys left for Lake Temagami by canoe. During the long trip he experienced his first taste of portaging heavy loads over difficult trails. The Guppys found work for the summer as guides at the recently constructed Temagami Inn on Temagami Island. With no experience, Belaney was forced to work at the inn as a "chore-boy." He returned home to Hastings for a short visit during the winter of 1907-1908, perhaps to ask for money from his aunts. He learned then that his father had been killed in a drunken brawl in the United States.[2]: 37–39

Belaney returned to Temagami in 1908 and continued working as a chore-boy at the Temagami Inn. According to Donald B. Smith, "He set out to lose the remaining traces of his English accent. He refined his story of his Indian boyhood in Mexico and the American Southwest."[2]: 39 It was there that he met Angele Egwuna, who was working at the inn as a kitchen-helper. She spoke little English and he little Ojibwa, but a friendship developed. Through Angele he also met members of her family, who called him "gitchi-saganash" (tall Englishman). Her uncle gave him the nickname "ko-hom-see" (little owl), a name that would be transformed years later into “Grey Owl.”

The Egwunas invited Belaney to spend the winter of 1909-1910 trapping with them in the bush to the east of the south arm of Lake Temagami.

That winter Archie learned how the Temagami Ojibwa harvested their hunting territories, taking only those animals required for clothing and for food, leaving the rest to breed. They took only the increase. The Indians farmed the beaver most carefully, keeping count of the number of occupants, old and young, of each lodge.[2]: 42

The time with the Egwunas improved both his proficiency with the Ojibwa language and the skills he needed to survive and make a living in the bush. Belaney would later report this as his "formal adoption" by the Ojibwa. The boy from Hastings was finally living the life he had dreamed of.[2]: 39–42

In the summers of 1910 and 1911, Belaney worked as a guide at Camp Keewaydin, an American boys’ camp on Lake Temagami. On August 23 he and Angele Egwuna were married on Bear Island in a Christian ceremony. In spring 1911 their daughter Agnes was born.[2]: 43–44

There is no clear record of Belaney's life in the winter of 1911-1912.[2]: 45 He next surfaces, alone, in the summer of 1912 in Biscotasing. He worked in the surrounding area as a forest ranger during the summers of 1912-1914 and spent the winters in the bush on the trapline. In Bisco, Belaney began a relationship with Marie Girard, a Metis woman who worked as a maid in the boarding-house where he stayed. At his invitation she joined him on his trapline during the winter of 1913-14.[2]: 47–52

There is again no clear record of Belaney's life in the winter of 1914-1915.[2]: 52 In June, 1915, he sailed for England with the Canadian Army. Marie Girard died of tuberculosis in the fall of 1915, shortly after giving birth to their son, John Jero.[2]: 53 In his first years in Canada, Belaney had established himself as a backcountry woodsman, with a keen appreciation for the wilderness. His debut as husband and father had not been a success.

In the Canadian Army

Belaney enlisted with the Canadian Overseas Expeditionary Force on May 6, 1915 during the First World War.[lower-alpha 2] In June he was shipped to England and initially assigned to the 23rd Reserve Battalion in Kent. He later joined the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), known as the Black Watch, and was shipped to the front line in France, where he served as a sniper. Fellow soldiers accepted his assumed Indian identity, with one writing that he "...saw him squirm up muddy hills in a way no white man could. He had all the actions and features of an Indian.... Never in all my life did I ever meet a man who was better able to hide when we would go out onto No Man’s Land."[2]: 55–58

Belaney was wounded in the right wrist in January 15, 1916. Then on April 23, he was shot in the right foot, a serious injury from which he never fully recovered. He was shipped back to England, where he was treated in various hospitals. From November 1916 to March 1917, he convalesced in the Canadian Military Hospital in his home town of Hastings.[2]: 58–60

Encouraged by his aunts, Belaney renewed his childhood friendship with Florence (Ivy) Holmes. Ivy, then 26, was an accomplished professional dancer, who had travelled extensively in Europe. Acquainted with her since childhood, he dispensed with the pretense of being Indian. She found that his stories about canoeing in Canada made the "backwoods sound terribly attractive." Belaney was silent about his wife and child back in Canada. They were married on February 10, 1917.[2]: 61–63

The couple decided that Belaney would return to Canada and establish himself near Biscotasing, then send for Ivy, who "looked forward to seeing his beloved wilderness." Exactly how he thought that plan would work out, with a legal wife and child no more than 100 kilometers away and (as far as he knew) a mistress in the same town, is a mystery. Belaney left for Canada on September 19, 1917. Ivy never saw him again. He wrote to her for a year until he finally admitted that he was already married. Ivy divorced him in 1921.[2]: 63, 68

Back to Canada

Belaney returned to Canada in September, 1917, and was discharged from the army at the end of November. His most pressing concern was his wounded foot, which was painful and limited his mobility - an unfortunate prospect for someone who wanted to go back into the bush. In October he received treatment at a hospital in Toronto, but achieved little success. He had other worries: What to do about his first wife, Angele, and his daughter Agnes? What to do about his second wife, Ivy, still in England and expecting to be sent for? What to do about his illegitimate son, Johnny, born to his deceased mistress Marie? After meeting with Angele, he returned to Biscotasing at the end of 1917, alone.[2]: 64–65

Belaney soon gained a reputation for drunkenness and disorderly conduct in Bisco.[2]: 68–69 Despite this, he made a favorable impression on many people, one person recalling "[I] liked immensely this endearing rebel. Archie was one of the nicest things that happened to me when I was growing up."[2]: 71

Belaney spent much of 1918 recuperating and gradually regained control of his right foot, but the disability remained for the rest of his life, with his foot sometimes swelling to twice its normal size.[2]: 68 He did not approach Johnny and the boy did not learn who his father was till years later.[2]: 67 He finally admitted to Ivy that he was already married, which ended their relationship. (He would be served divorce papers in 1921.) Now he had a new worry: His aunts were furious with him and regarded his treatment of Angele and Ivy as "nothing less than diabolical."[2]: 71

In the summer of 1919, Belaney worked on a survey party in the bush. A co-worker recalled "The 'Mexican half-breed' had an unattractive side. 'He was taciturn and morose, with a violent, almost maniacal temper.'"[2]: 68

His best friends in Bisco were the Espaniels, an Indigenous family with whom he lived in the early 1920s. He joined them for two winters trapping at Indian Lake on the east branch of the Spanish River. Belaney also maintained a cabin on his hunting ground nearby at Mozhabong Lake.

From the Espaniels, Archie learned the “Indian way of doing things” — which in Jim Espaniel’s words “the white man calls conservation.” Archie must keep track of the number of lodges in his hunting territory and the age of their inhabitants. Most important of all, he must leave a pair behind in each lodge.[2]: 71–72

In the summers of 1920 and 1921, he worked as the deputy forest ranger on the Mississagi Forest Reserve.

Here Archie was at his best, on the five three-week tours through the huge reserve, checking on the summer ranger stations situated 50 to 60 kilometres from each other.... [Belaney] loved the wilderness. He insisted that [the men under his supervision] carefully check all camping sites for fire and also work on the trails, keeping up the portages to the different lakes in their district, allowing access in case of a fire.[2]: 70

Worried about the logging of Ontario's remaining old-growth pine forests, Belaney wanted the Mississagi area made into a park. In a fledgling attempt at conservationism, he posted signs saying "GOD MADE THIS COUNTRY FOR THE TREES DON’T BURN IT UP AND MAKE IT LOOK LIKE HELL” and “GOD MADE THE COUNTRY BUT MAN DESTROYED IT.”[2]: 70

Inspired by his boyhood reading of authors such as Fenimore Cooper and Longfellow, Belaney invented his own elaborately choreographed "war dance," which "...surprised the local Ojibwa and Cree for, as fur buyer Jack Leve put it, 'the Bisco Indians didn’t know his brand of Indian lore.'"[2]: 73 Local reactions to the war dance were mixed, with some people saying it was good fun, while others said it was just an excuse for drinking. Some Indigenous men joined in, while others thought the dance was evil.[2]: 73

Belaney's big day arrived on Victoria Day, May 23, 1923. The Sudbury Star reported: "War Dance Given at Biscotasing. A Big Celebration Held on Victoria Day. In honour of the good queen to which his grandfather and namesake had sent his epic poem, The Hundred Days of Napoleon, Archie put on the greatest war dance of his life."[2]: 74

In April, 1925, a particularly egregious piece of misbehaviour resulted in an arrest warrant being issued for Belaney. Soon after, he left Bisco for good, returning to Temagami and taking up again with Angele, who bore him a second daughter, Flora, in 1926. Amazingly, there is no record of Angele ever reproaching him for his treatment of her, and she appeared to accept his wayward conduct to the end.

Angele never forgot his last words to her that fall: “I go away. I will come back sometime. I like travel.” She still loved him, and as she knew that he “liked to go and travel in the Indian way,” she made him a new leather costume. She saw him off at the train station in the fall of 1925. Angele never saw Archie again.[2]: 75–76

By then, Belaney had already begun his fourth relationship.

Transformation into Grey Owl

The transformation of Archie Belaney from a backcountry woodsman into the popular writer and public speaker Grey Owl began in 1925. His concern, expressed in books, articles and public appearances, was the vanishing wilderness and the consequences of this for the creatures living in it, including man. His message was “Remember you belong to nature, not it to you.”[6]: 127

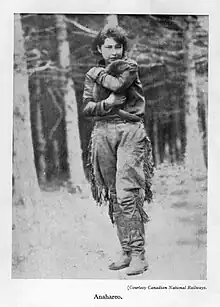

In the late summer of 1925, 37-year-old Belaney began courting 19-year-old Gertrude Bernard. Their relationship would last eleven years, till 1936,[6]: 111 and prove to be both tumultuous and a crucial factor in Belaney's transformation.[7] They met at Camp Wabikon on Lake Temagami, where he was working as a guide.[8]: 1ff She was of Mohawk Algonquin descent.[9] Her father's nickname for her was “Pony,” but Belaney would give her another name, “Anahareo,” which he derived from “Naharrenou,” the name of the Apache chief who was her great-great-grandfather.[8]: 18, 33 According to her account in Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl, Belaney's answer to her father's question about his background was this: “I come from Mexico. [M]y father was Scotch and my mother was an Apache Indian.”[8]: 9 Anahareo did not discover Belaney's true identity until his death and exposure in 1938.[8]: 180

In February, 1926, Anahareo joined Belaney in the Abitibi region of northwestern Quebec, where he was earning a living trapping.[8]: 12 Their courtship was eventful at times, with Anahareo stabbing Belaney with a knife at one point.[8]: 63 In summer Belaney proposed to her. Due to his undissolved marriage to his first wife, Angele Egwuna, the couple could not marry under Canadian law, but the chief of the Lac Simon Band of Indians declared them husband and wife.[6]: 52

After a summer working as a fire ranger in Quebec, Belaney was back trapping again in the winter of 1926/27. Anahareo accompanied him on the trapline and was horrified by what she experienced:

Nothing in her small-town up-bringing had prepared her for the heart-wrenching sight of the frozen corpses of animals who had died in agony while trying desperately to escape from the unyielding metal jaws of the leghold traps. Nor could she bear to watch as Archie used the wooden handle of his axe to club to death those who were still living.[6]: 52

She attempted to make him see the torture that animals suffered when they were caught in traps.[10] According to the account given in Pilgrims of the Wild, Belaney located a beaver lodge, which he knew to be occupied by a mother beaver, and set a trap for her. When the mother beaver was caught, he began to canoe away to the cries of the kittens, which greatly resemble the sound of human infants. Anahareo begged him to set the mother free, but, needing the money from the beaver's pelt, he could not be swayed. The next day he rescued the baby beavers, which the couple adopted.[11]: 27–33 As Albert Braz stated in his article "St. Archie of the Wild", "[P]rimarily because of this episode, Belaney comes to believe that it is 'monstrous' to hunt such creatures and determines to 'study them' rather than 'persecuting them further.'"[10]: 212

In 1928, lured by stories of abundant wildlife and bush, Belaney and Anahareo, along with the adopted beavers, McGinnis and McGinty, moved to southeastern Quebec, where they were to reside until 1931. Their intention was to set up a beaver colony, where the beavers would be protected and could be studied. Arriving in Cabano in autumn to find the vicinity heavily logged and unsuitable, they moved to the area of Lake Touladi, east of Lake Témiscouata, and built a cabin on Birch Lake, where they spent Christmas and the rest of winter. They found a family of beaver in the vicinity.[6]: 61, 62, 66 That winter Grey Owl wrote his first article, "The Passing of the Last Frontier", which was published in 1929 under the name A.S. Belaney in the English outdoors magazine Country Life.[2]: 297

In March 1929, Belaney received a check from Country Life for the article and a request for the book that would be published in 1931 as The Men of the Last Frontier. An unfortunate incident occurred that put an end to their dream of founding a beaver colony on Birch Lake: A friend of theirs, Dave White Stone, had arrived at their cabin while they were away and, unaware of their plans, had trapped the beavers that were to be the start of the colony. Then yet another unfortunate incident occurred: The two beavers, McGinnis and McGinty, disappeared. The couple was devastated by the incidents. Dave White Stone found them two beaver kittens, one of which soon died. They adopted the surviving beaver, naming it Jelly Roll, and moved to a cabin on Hay Lake near Cabano. [6]: 66–69 At the end of summer the three relocated for some time to the nearby resort town of Metis, where Belaney gave his first public lecture.[12][6]: 69 He moved back to Hay Lake with Jelly Roll, while Anahareo left to work in northern Quebec.

In 1930, Belaney published his first article for the periodical Canadian Forest and Outdoors, "The Vanishing Life of the Wild.”[2]: 297 Under the name "Grey Owl," he wrote many articles for the periodical in the following years, becoming increasingly known in Canada and the United States. In June he inadvertently caught a beaver in a trap, which he nursed back to health and named Rawhide.[6]: 76 His writing brought him into contact with Gordon Dallyn, the editor of Canadian Forest and Outdoors, who introduced him to James Harkin, the Commissioner of National Parks.[2]: 89 In the spring, he received a visit from the Parks Branch publicity director, J.C. Campbell[6]: 71 The Parks Branch commissioned the first beaver film, The Beaver People,[13] which featured the two beavers, as well as Anahareo and Belaney (identified as Grey Owl), and was shot in the summer of 1930.[14]: 54, 100 [2]: 299 [lower-alpha 3] In correspondence with Country Life, Belaney signed himself "Grey Owl" for the first time in November.[2]: 85

In January 1931, Belaney, in the persona of Grey Owl, gave a talk at the annual convention of the Canadian Forestry Association in Montreal, where the film was shown in public for the first time. “The event was a huge success. It set the pattern for numerous speeches Grey Owl was to give, dressed in his Indian regalia, with films and his tame beaver to illustrate his stories.”[6]: 79

In late 1931, Grey Owl's first book, on which he had been working for two years, finally appeared. To Grey Owl's chagrin, the publisher, Country Life, changed the title from The Vanishing Frontier to The Men of the Last Frontier without consulting him. He wrote to the publisher:

That you changed the title shows that you, at least, missed the entire point of the book. You still believe that man as such is pre-eminent, governs the powers of Nature. So he does, to a large extent, in civilization, but not on the Frontier, until that Frontier has been removed. ... I speak of Nature, not men; they are incidental, used to illustrate a point only.[2]: 115

Among other topics the book describes the plight of the beaver in the face of extensive trapping and raises concerns about the future of the Canadian wilderness and wildlife. The demand for beaver pelts in the 1920s and 30s had increased so much that the beaver was on the verge of extinction in Canada. Trappers were being drawn to the forests in higher numbers than ever before. Grey Owl argued that the only way to save the animal was to stop the influx of trappers.[15]: 151 This was highly unlikely during the Depression, "beavers [being] to the north what gold was to the west".[15]: 144 Though the book focusses on the beaver, Grey Owl also used the animal as “...representative not only of all North American Wild Life but of the wilderness itself...”[16] He believed that Canada's wilderness and vast open spaces, both of which were fast disappearing, were what made it unique in the world.[10]: p. 207 Grey Owl also raised concerns about how the Canadian government and logging industry were working together to exploit the forests and attempt to replace them with "synthetic forests," all the while projecting a false image of forest preservation.[15]: 172, 173 He wrote:

So we have the highly-diverting spectacle of one man, standing in the midst of ten million acres of stumps and arid desolation, planting with a shovel a little tree ten inches high, to be the cornerstone of a new and synthetic forest, urged on to the deed by a deputation of smug and smiling profiteers, who do not really care if the tree matures or not unless their descendants are to be engaged in the lumbering business.[15]: 173

The Men of the Last Frontier was Grey Owl's desperate wakeup call to the people of Canada to resist the destruction of their wilderness.

Work for Dominion Parks Branch

In the spring of 1931, Grey Owl accepted an offer of employment from the Parks Branch as a conservationist at the Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba. He and Anahareo, with the beavers, left Quebec, bound for the new job in the west, where a cabin had been built for them on Beaver Lodge Lake. In June, a second beaver film was produced.[6]: 82 This film, The Beaver Family,[17] was shot by the cameraman W. J. Oliver, and released in 1932.[14]: 54, 100 [2]: 299 Grey Owl would work with W.J. Oliver on more beaver films in the coming years. The story of their first meeting is both amusing and revealing:

The friendship between Grey Owl and Bill Oliver began rather awkwardly one June day in 1931.... Grey Owl greeted him with this remark: “So you're the cameraman. I may as well tell you I have not much use for white men.” When Bill asked why, his host replied: “I have never had the pleasure of meeting many who did not want to deface God's earth.” Only after Grey Owl's death did Bill Oliver realize the irony of the situation. The Indian making these remarks was born and raised in Hastings, Sussex, just fifty kilometers or so from the village of Ash (near Canterbury), Bill's hometown.[2]: 101

Beaver Lodge Lake proved to be unsuitable for the beavers, as a summer drought resulted in the water becoming stagnant.[1]: 223 In October the group relocated to Lake Ajawaan in Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan. The bigger waterways of the park were found to be a better habitat for beaver, as the lake at Riding Mountain National Park had a risk of freezing to the bottom during winter.[2]: 108 They found the park ideal for their needs, since it was isolated, heavily wooded and teeming with wildlife. Grey Owl also had a favourable impression of the Superintendent of the Park, Major J.A. Wood.[1]: 223 A cabin, known thereafter as Beaver Lodge, was built for them according to Grey Owl's specifications. There the third beaver film, Strange Doings in Beaverland, was shot by W. J. Oliver in 1932.[14]: 54, 100 [2]: 299 Oliver also took many photographs of Grey Owl looking "consciously Indian," which were used as publicity for his lecturing tours.[2]: 124 The photographs were also used as illustrations in Grey Owl's works.

Between 1936 and his death he was informally visited at his base by the then Governor-General, Lord Tweedsmuir, an admirer of Grey Owl's writings on wildlife, an event photographed by Shuldham Redfern.[18]

During a publication tour of Canada, Grey Owl met Yvonne Perrier, a French Canadian woman. In November 1936 they married.

Tours in North America and Britain

In 1935–36 and 1937–38, Grey Owl toured extensively in Canada, the United States and Britain. Arrayed in Indian regalia, with his silent beaver films playing behind him, he lectured to packed halls, including a Royal Command Performance at Buckingham Palace in 1937, attended by King George VI and the young Princess Elizabeth. Grey Owl was impressed by the King, who struck him as a “keen woodsman.” In parting, it is reported that Grey Owl put out his hand to the King and said “Well, good-bye, Brother, and good luck to you.”[2]: 188–189 The tours, organized by his publisher Lovat Dickson, also served to promote his book Pilgrims of the Wild, whose sales would eventually reach 50,000 in the United Kingdom.[2]: 115

In From the Land of Shadows: the Making of Grey Owl, Donald B. Smith described Grey Owl's performance in Hastings, England in late 1935:

After his words of greeting from the Hastings stage, Grey Owl showed “Pilgrims of the Wild,” an eleven minute film about his life with his wife, Anahareo, at his home in distant Saskatchewan. The film had been shot at Beaver Lodge, in Prince Albert National Park in September 1935, a month before Grey Owl left Canada for Britain. It showed him and his beautiful Indian wife canoeing, portaging and calling the beaver...

The film took its title from Grey Owl's autobiography published the previous year. In this moving account the former trapper told the story of how he had decided to abandon the hunt and to work instead for the conservation of the beaver and all wildlife...

While the silent film ran, the lecturer moved to and fro across the front of the screen recounting tales of his beloved northern Canada. He told stories about wildlife--particularly about those intelligent, hard-working animals he lived with: the beaver, Canada's national animal. He talked directly to his audience, and used no notes. His animated dialogue and his second, third and fourth films magically transported his listeners from the narrow streets of Hastings to the vast, unbroken Canadian forests.”[2]: 4

On March 26, 1938, Grey Owl appeared at a packed Massey Hall in Toronto. “On that evening nearly three thousand Canadians gave him the greatest ovation of his life.” He then took the Canadian Pacific transcontinental train to Regina, where he gave his last lecture on March 29.[2]: 209

Alcohol use

Belaney started drinking when he arrived in Canada as a young man and was a lifelong drinker. "If one accepts alcoholism as 'recurring trouble, problems or difficulties associating with drinking,' Archie by 1930 had become an alcoholic."[2]: 85, 86 His favorite drink, according to Anahareo, was "Johnny Dewar's Extra Special."[8]: 133 He would also drink vanilla extract and occasionally make his own moonshine.[2]: 86

Following his return from service in the First World War, Belaney's use of alcohol increased, and it was not unusual for him to appear drunk in public.[19] On the ship back to Canada from his 1935 British tour, it was noted that he "drank heavily, ate only onions and was noticeably ill."[20][lower-alpha 4]

Excessive alcohol consumption compromised Grey Owl's position with the Dominion Parks Branch in Ottawa. He was supposed to meet a group of important governmental officials at the studio of Yousuf Karsh, who had organised a dinner in his honour. However, as the dinner began, Grey Owl was absent. Karsh later found him "raising a drunken row in the bar."[2]: 156 This public display of a Parks Branch employee drunk in public caused James Harkin to have to defend Grey Owl's position within Parks Branch, writing to the Assistant Deputy Minister Roy A. Gibson "I am sorry to hear that Grey Owl has been indulging too freely in liquor. As a matter of fact, with so much Indian blood in his veins I suppose that it is inevitable that from time to time he will break out in this connection."[2]: 157 His consumption of alcohol at Prince Albert National Park created more friction between himself and Parks Branch as he was seen to "indulge too freely in liquor."[19]

Conservationist views

Initially, Grey Owl's efforts and conservation were focused towards the beaver up North; however, with the publication of The Men of the Last Frontier, his conservation efforts came to include all wild animals.[1]: 219 While he had at one time been a fur trapper, he came to believe that "the trap, the rifle, and poison" would some day result in "the Dwellers in the forest to come to an end too."[1]: 219 He expressed in Pilgrims of the Wild how humanity's rush to exploit natural resources for commercial value overlooks "the capabilities and possibilities of the wild creatures involved in it."[21] It was this "commodification of all living things that was responsible for the destruction from the beaver."[22] Grey Owl expressed that if there were "temporary at least" protection for fur bearing animals, then humanity would "see the almost human response to kindness" from animals.[1]: 219 He called for people to remember "you belong to Nature, not it to you."[23][22] Men of the Last Frontier was first called The Vanishing Frontier, and subsequently named Men of the Last Frontier by the publishers, which he felt "missed the entire point of the book" as he "spoke of nature, not men."[1]: 218 The changing of the title exemplified for him the conception of people "that man governs the powers of nature."[1]: 218

Death

The tours were fatiguing for Grey Owl and his years of alcoholism weakened him. In April 1938, he returned to Beaver Lodge, his cabin at Ajawaan Lake. Five days later, he was found unconscious on the floor of the cabin. Although taken to Prince Albert hospital for treatment, he died of pneumonia on April 13, 1938. He was buried near his cabin.

His first wife Angele proved her marriage and, although she had not seen him for several years, inherited most of his estate. After their deaths, Anahareo and Shirley Dawn (died June 3, 1984) in turn were buried at Ajawaan Lake.

Exposure

Doubts about Grey Owl's supposed First Nation identity had been circulating and stories were published immediately after his death. The North Bay Nugget newspaper ran the first exposé the day of his death, a story which they had been holding for three years.[24] This was followed up by international news organisations, such as The Times. His publisher Lovat Dickson tried to prove Belaney's claimed identity, but had to admit that his friend had lied to him. His popularity and support for his causes led The Ottawa Citizen to conclude, "Of course, the value of his work is not jeopardized. His attainments as a writer and naturalist will survive." This opinion was widely shared in the UK national press.[24]

While his writings showed his deep knowledge and concern about the environment, Belaney's account of his origins as "Grey Owl" was fictional. The consequences of the revelation were dramatic. Publishers immediately ceased producing his books under the name "Grey Owl". In some cases, his books were withdrawn from publication. This in turn affected the conservation causes with which Belaney had been associated, resulting in a decrease in donations.

Posthumous recognition

In 1972 the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) produced a documentary special on Grey Owl, directed by Nancy Ryley. In 1999, the film Grey Owl was released. It was directed by Richard Attenborough and starred Pierce Brosnan. The film received mixed reviews and received no theatrical release in the United States.

In June 1997, the mayor of Hastings and the borough's Member of Parliament (MP) (Michael Foster) unveiled a plaque in his honor on the house at 32 St. James Road, Hastings, East Sussex, where he was born.[25][26]

The ranger station at Hastings Country Park, four miles to the east of Hastings, also has a commemorative plaque to Grey Owl. A full-size replica of his Canadian lakeside cabin is in Hastings Museum at Summerfields. An exhibition of memorabilia and a commemorative plaque are at the house at 36 St. Mary's Terrace where he lived with his grandmother and aunts.[25]

The cabin in Riding Mountain National Park where he resided for six months in 1931 has been designated as a Federal Heritage Building and was restored in June 2019.[27]

The cabin he had built in the 1930s still stands in Prince Albert National Park and can be reached by foot (20 kilometer hike) or by canoe (a 16 km paddle).[28]

Grey Owl's names

Belaney had a number of names in his life:

- Archibald Stansfeld Belaney. This was his full, legal name at birth and it was used in the shortened form "Archibald Belaney" throughout his life: Under this name, he enlisted in the army, received disability payments, was employed by Dominion Parks Branch, etc.[lower-alpha 5] He hated the name "Archibald" and preferred to be called "Archie". Even after adopting the name "Grey Owl" for certain purposes, he remained "Archie" to friends and acquaintances. Between themselves, he and Anahareo were always "Archie" and "Gertie."

- Grey Owl. Belaney started using this name in the 1930s in his publications and lectures and it is under this name that he is commonly known to the public. He also used the name in correspondence.[2]: 85

- Archie Grey Owl. Belaney made some abortive attempts to avoid his legal surname by enlisting "Grey Owl" in that role. He used this name in his Record of Employment at Prince Albert National Park. "The civil service, however, continued unimaginatively to address him in all correspondence as “A. Bellaney.” At least they spelt his name incorrectly."[2]: 118

- Wa-sha-quon-asin. The authorship of his books is attributed to this name as well as to "Grey Owl." It actually means "white beak owl” in Ojibwa, but for dramatic effect Belaney would translate it as “He Who Walks By Night.”[2]: 91–92

- Ko-hom-see. This name ("Little Owl") was an affectionate nickname given to Belaney by the Egwuna family, since they regarded him as “the young owl who sits taking everything in." The name was a precursor of “Grey Owl.”[2]: 41

- Anaquoness. This is a nickname that Belaney got in Bisco due to the unusual Mexican sombrero he wore there. He translated the Ojibwa word as “Little Hat.”[2]: 65

- Archie McNeil. Belaney married his third wife, Yvonne Perrier, under this name, fearing a charge of bigamy due to his undissolved marriage with his first wife. In one of the more elaborate fictions he created about his past, his grandfather, George McNeil, was portrayed as third generation Scottish in the United States.[2]: 171–172

Relationships with women

Belaney had known relationships with five women and fathered three known children:[6]: 19, 28, 32, 36, 45, 47, 111, 118

- Angele Egwuna, married in 1910 in Canada. Daughters Agnes Belaney, born in 1911, Flora Belaney, born in 1926.

- Marie Girard, relationship from 1912-15 in Canada. Son Johnny Jero, born in 1915.

- Florence (Ivy) Holmes, married in 1917 in England. Divorced 1921.

- Gertrude Bernard (Anahareo), relationship from 1925-36 in Canada. Daughter Dawn, born in 1932.

- Yvonne Perrier, married in 1936 in Canada. (Belaney was married under the name “McNeil”, due to his undissolved marriage with Angele Egwuna.)

Grey Owl's writings

Books

- The Men of the Last Frontier. Toronto: Dundurn Press (2011).

- Pilgrims of the Wild. Toronto: Dundurn Press (2010).

- The Adventures of Sajo and her Beaver People. London: Lovat Dickson Ltd. (1935).

- Tales of an Empty Cabin. London: Lovat Dickson Ltd. (1937).

- The Tree. London: Lovat Dickson Ltd. (1937). (A long story from Tales of an Empty Cabin, published separately as a small volume.)

Collected editions

- The collected works of Grey Owl: Three Complete and Unabridged Canadian classics. Toronto: Prospero (1999).

- A Book of Grey Owl: Selected Wildlife Stories. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada (1989).

Articles

Articles published in Canadian Forest and Outdoors with excerpts archived online.[30]

- "King of the Beaver People" (January 1931)

- "A Day in a Hidden Town" (April 1931)

- "A Mess of Pottage" (May 1931)

- "The Perils of Woods Travel" (September 1931)

- "Indian Legends and Lore" (October 1931)

- "A Philosophy of the Wild" (December 1931)

Other articles:

- "A Description of the Fall Activities of Beaver, with some remarks on Conservation", in Harper Cory's book Grey Owl and the Beaver (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1935).

Translations

- Ambassadeur des bêtes. (Ambassador of the Beasts, was: Part 2 of Tales of an Empty Cabin) Translation by Simonne Ratel. Paris : Hatier-Boivin, 1956

- Саджо и её бобры. Перевод с английского Аллы Макаровой. Предисловие Михаила Пришвина. Москва: Детгиз, 1958

- Cаджо та її бобри. Переклад з англійської Соломії Павличко., Київ: «Веселка», 1986

- Historia opuszczonego szałasu Translation by Aleksander Dobrot [Wiktor Grosz]. Warsaw (Poland): Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Rój" 1939

- Két kicsi hód (The Adventures of Sajo and Her Beaver People). Translated from the English by Ervin Baktay (1957); illustrations by Péter Szecskó. Hungary, Budapest : Móra Ferenc Könyvkiadó, 1957.

- Ludzie z ostatniej granicy Translation by Aleksander Dobrot [Wiktor Grosz]. Warsaw (Poland): Wydawnictwo J. Przeworskiego, 1939

- Индијанка Саџо и њени дабрићи. Translation by Виктор Финк. Illustrated by Михаило Писањук. Covers Ида Ћирић. Дечији Свет, Младо Поколеље, Београд (Belgrade, Serbia), 1967

- Oameni și animale, pelerini ai ținuturilor sălbatice. Translation into Romanian by Viorica Vizante. Iasi, Junimea, 1974

- Рассказы опустевшей хижины. Перевод и предисловие Аллы Макаровой. Художник Б.Жутовский. Москва: Молодая гвардия, 1974

- Pielgrzymi Puszczy Translation by Aleksander Dobrot [Wiktor Grosz]. Warsaw (Poland): Wydawnictwo J. Przeworskiego, 1937

- Pilgrims of the Wild. Éd. ordinaire. Translation by Jeanne Roche-Mazon. Paris : Éditions contemporaines, 1951

- Récits de la cabane abandonnée. (Part1 of Tales of an Empty Cabin) Translation by Jeanne-Roche-Mazon. Paris : Éditions contemporaines, 1951

- Sajo et ses castors (The Adventures of Sajo and Her Beaver People) Translated from the English by Charlotte and Marie-Louise Pressoir; illustrations by Pierre Le Guen. Paris : Société nouvelle des éditions G.P., 1963

- Sajon ja hänen majavainsa seikkailut Translation by J.F. Ruotsalainen. WSOY Finland 1936

- Sejdżio i jej bobry Translation by Aleksander Dobrot [Wiktor Grosz]. Warsaw (Poland): Wydawnictwo J. Przeworskiego, 1938

- Seidzo ja tema kobraste seiklused (The adventures of Sajo and her Beaver people) Translation into Estonian by E. Heinaste, Tallinn, 1967

See also

Notes

- Grey Owl gave his publisher and future biographer, Lovat Dickson, the following account of his origins:

He was the son of a Scottish father and Apache mother. He claimed his father was a man named George MacNeil, who had been a scout during the 1870's Indian Wars in the southwestern United States. Grey Owl said his mother was Katherine Cochise of the Apache Jicarilla band. He further said that both parents had been part of the Wild Bill Hickok Western show that toured England. Grey Owl claimed to have been born in 1888 in Hermosillo, Mexico, while his parents were performing there.[1]: 3

- His Regimental number with the CEF was 415259. His attestation papers show that he claimed to have been born in Montreal on September 18, 1888, had no next of kin and was not married. He stated his trade was "trapper" and that he had previously served in the "Mexican Scouts, 28th Dragoons."[5]

- This film was not shot by W.J. Oliver, nor was it shot in 1928, as some sources state.[14]: 54, 100

- Grey Owl was accompanied back to Canada by Betty Summervell (Summy).

When she momentarily left for her own cabin ... Grey Owl acted with lightening speed. He either took out of a suitcase, or purchased on the ship, a number of bottles of whisky, which he hid under his bunk. He drank whenever she left the cabin... After three days ... the intoxicated Grey Owl looked like a ghost. Finally, Summy solved the mystery. During the third day at sea the ship lurched, and a bottle rolled out from under Grey Owl's bunk.[2]: 129, 130

- The possession of a Christian name does not argue against Belaney's Indigenousness. Every Canadian citizen needs a name in the conventional "given name/surname" format, usually completely or partially Christian. The Indian Act forced Indigenous people to adopt made-up names to function in Canadian society:

Traditionally, First Nations people had neither a Christian name nor a surname - they had hereditary names, spirit names, family names, clan names, animal names or nicknames to name but a few.... Traditional naming practices did not make sense to the Indian agents, charged with recording the names of all people living on reserves.... [G]enerally the agents assigned each man a Christian name and more often than not, a non-native surname. Women were given Christian names and assigned the surname of their fathers or husbands.[29]

Belaney's first wife's name was "Angele Egwuna" (a combination of Christian given name and traditional surname), while Anahareo had the completely Christian name "Gertrude Bernard." Thus there would be nothing remarkable in Belaney's having a completely Christian name as well as a traditional animal name.

References

- Dickson, Lovat (1973). Wilderness Man: The Strange Story of Grey Owl. Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada.

- Smith, Donald B. (1990). From the Land of Shadows: the Making of Grey Owl. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books.

- Tina Loo, States of Nature: Conserving Canada's Wildlife in the Twentieth Century, Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006, p. 113.

- Lovat Dickson (1939). Half-Breed: The Story of Grey Owl. London: Peter Davis. p. 47.

- "Personnel Records of the First World War". Library and Archives Canada. February 7, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- Billinghurst, Jane (1999). The Many Faces of Archie Belaney, Grey Owl. Vancouver: Grey Stone Books.

- Albert Braz. Apostate Englishman: Grey Owl the Writer and the Myths, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2015, p. 11

- Anahareo (1972). Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl. Toronto: New Press.

- McCall, Sophie. Afterword. Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl by Anahareo, Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2014, p. 227

- Braz, Albert (2007). "St. Archie of the Wild. Grey Owl's Account of His 'Natural' Conversion". In Fiamengo, Janice (ed.). Other Selves: Animals in the Canadian Literary Imagination. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. pp. 206–226. ISBN 9780776617701.

- Grey Owl (2010). Pilgrims of the Wild. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

- Kerry Martin.“When Anahareo and Grey Owl Came to Metis”

- "The Beaver People". National Film Board of Canada.

- Jameson, Sheilagh S. (1984). W.J. Oliver: Life Through a Master's Lens. Calgary: Glenbow Museum.

- Grey Owl (2011). The Men of the Last Frontier. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

- Grey Owl. Tales of an Empty Cabin, Toronto: Macmillan of Canada, p. ix

- "The Beaver Family". National Film Board of Canada.

- Smith, Janet Adam (1979). John Buchan and His World. Thames & Hudson. p. 105. ISBN 0-500-13067-1.

- Dane Lanken, "The Vision of Grey Owl," Canadian Geographic 119 (1999).

- Peter Unwin, "The Fabulations of Grey Owl," Canada's History 79, no. 2 (April 1999).

- Gnarowski, Michael (2010). Pilgrims of the Wild. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn. p. 27.

- Loo, Tina (2006). States of Nature: Conserving Canada's Wildlife in the Twentieth Century. Vancouver, British Columbia: UBC Press. p. 113.

- Donald B. Smith. "Biography – BELANEY, ARCHIBALD STANSFELD, known as Grey Owl and Wa-sha-quon-asin – Volume XVI (1931–1940) –". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- "Grey Owl", The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed 4 Feb 2010

- Grey Owl's Hastings, 1066.net, accessed 19 Apr 2009

- The Canadian Guide to Britain, vol 1: England page 129

- Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (October 24, 2019). "Digging into the History of Grey Owl's Cabin with a Parks Canada Archaeologist and Restoration Crew – Riding Mountain National Park". www.pc.gc.ca. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- "Pilgrimage to Grey Owl's Legendary Cabin: By Foot or by Canoe – Prince Albert National Park". February 6, 2017.

- "The Indian Act Naming Policies". Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- Grey Owl

Further reading

Numerous books about Belaney have been published, including:

- Anahareo. Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl. Toronto: New Press, 1972.

- Attenborough, Richard, dir. Grey Owl. Screenplay by William Nicholson. Largo Entertainment, 1999.

- Atwood, Margaret. "The Grey Owl Syndrome", Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature. Oxford: Clarendon, 1995. 35–61.

- Billinghurst, Jane. Grey Owl: The Many Faces of Archie Belaney. Vancouver: Greystone Books, 1999.

- Dickson, Lovat. Wilderness Man: The Strange Story of Grey Owl. 1974.

- Dickson, Lovat. The Green Leaf: A Memorial to Grey Owl, London, 1938.

- Dickson, Lovat. Half-Breed; The Story of Grey Owl, London, 1939.

- Smith, Donald B. From the Land of Shadows: the Making of Grey Owl. 1990.

- Ruffo, Armand Garnet, Grey Owl: The Mystery of Archie Belaney. 1996.

External links

- "Grey Owl". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

- Works by Archibald Stansfeld Belaney at Faded Page (Canada)

- See the silent films The Beaver People (1930) and The Beaver Family (1931), National Film Board of Canada.

- "Grey Owl", Prince Albert National Park

- Canadian Heroes in Fact and Fiction: Grey Owl, Library and Archives Canada website

- Grey Owl at IMDb

- Historica Minutes TV Commercial, Canadian Heritage