Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie

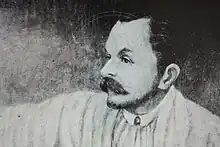

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie d'Arrast, listed in the Chambers Biographical Dictionary as Michel Arnaud d'Abbadie[1] (born 24 July 1815 in Dublin; died 8 November 1893 in Ciboure) was an Irish-born French and Basque explorer known for his travels in Ethiopia with his elder brother Antoine d'Abbadie d'Arrast. Arnaud was a geographer, ethnologist, linguist, familiar with the Abyssinian polemarch and an active witness to their battles and the life of their courts. The general account of the travels of the two brothers was published by Arnaud in 1868 under the title Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Ethiopie. The book has been translated into English ("Twelve Years in Upper Ethiopia").

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie | |

|---|---|

Arnaud-Michel d'Abbadie in Ethiopian clothes a few months before his death in 1893 | |

| Born | 24 July 1815 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 8 November 1893 (aged 78) Ciboure, France |

| Nationality | French, Basque |

| Citizenship | France |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Explorer, Geographer |

Early life

Arnaud's father, Michel Arnauld d'Abbadie (1772-1832), descended from an old family of lay abbots of Arrast, a commune in the canton of Mauléon. In 1791, to avoid the aftermath of the Revolution, Michel Arnauld emigrated first to Spain, then to England and Ireland, where he became a shipowner and imported wines from Spain. He married Eliza Thompson of Park (1779–1865), daughter of a doctor, on 18 July 1807 in Thurles, County Tipperary.[2]

Arnaud d'Abbadie, born July 24, 1815 in Dublin, was the fourth child and second son of six children:[3]

- Elisa (1808-1875), who married Alexandre Glais-Bizoin;

- Antoine (1810-1896);

- Celina (1811-1894),

- Arnaud Michel (1815-1893);

- Juilia (1820-1900), who married Bernard Cluzeau de Cléran;

- Charles Jean (1821-1901), who married Marie-Augustine-Émilie-Henriette Coulomb

Arnaud's father returned to France in 1820 and obtained from Louis XVIII the addition of d'Arrast to his patronymic name of Abbadie. It was only in 1883 that Arnaud, Charles and his son Arnauld Michel asked to legally add d'Arrast to their patronymic name.[4]

1815-1836

Until he was 12, Arnaud, like Antoine, was educated by a governess; he then entered the Lycée Henri-IV in Paris. Arnaud had a great ability to learn languages and spoke perfect English, Latin and Greek.

At seventeen, his friends introduced him to freemasonry as a benevolent philanthropic society. Arnaud was interested in this group, but on the day of his initiation was asked to take an oath not to reveal the secrets of the sect. It was a revelation for him: "If these men hide, it is because they are guilty. Only those who are ashamed of their deeds flee from the light." So he refused to take the oath.[5]

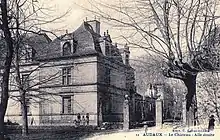

At twenty, Arnaud wanted to enlist in the military, because the colonization of Algeria fascinated him. However, his mother adamantly opposed a military career and sent him to Audaux in the Basque Country, on the lands of his ancestors. Arnaud travelled the Basque Country and learned Basque. He lived with his brother Antoine in the castle of Audaux.[6]

Arnaud knew of his elder brother's plan to explore Abyssinia and decided to accompany him and discover the sources of the Nile. .

Exploration of Abyssinia (1837-1849)

Antoine and Arnaud spent twelve years exploring Abyssinia, largely unknown to nineteenth-century Europeans, who had increasingly explored Africa, but they limited themselves at first to the great rivers. The geography, geodesy, geology and ethnography of vast African regions remained totally unknown, and the triangle within Harar-Mogadishu-Cape Guardafui on the Horn of Africa remained blank on the maps of 1840.

The territory was huge. Abyssinia's four provinces represented more than 300,000 km2. Conditions were extremely difficult. Wars were constant and loyal allies could become enemies from one day to the next. Historians call this period the Era of Princes or the Zemene Mesafint. Religious wars were numerous, between Catholics, Protestants, Muslims, Copts, animists and Jews. Linguistic barriers were numerous. The Ethiopian alphabet has 267 characters used by roughly thirty languages and dialects. Endemic diseases were numerous: typhus, leprosy and ophthalmia. The suspicions of colonial powers also hindered their research: British, Italians, Germans and Turks all suspected the Abbadie brothers of spying.

Arnaud wanted to locate the sources of the Nile. Antoine wanted to map the country and make geodetic and astronomical measurements. He invented new techniques to do so and the maps he produced were surpassed only with the arrival of aerial and satellite photography;

Both brothers were devout Catholics, from a family of lay abbots. Antoine said himself that without the events of 1793, he would sign: "Antoine d’Abbadie, abbé lai d’Arrast en Soule." They also went to the Ethiopian mountains to help the declining Christian religion, threatened by a conquering Islam.[7] Arnaud wanted to rebuild the formerly Christian empire of Ethiopia at the expense of the Muslim occupation. In addition, he wanted to link the state to the "protection" of France and thus thwart British colonization in East Africa.

To travel to this hostile country, they needed to know its habits and customs. They inquired as best they could before they left France and once there, their ethnological, linguistic, political observations were of the utmost importance;

Stay in Abyssinia

The two brothers were very different. Antoine, the scientist, seemed the most conciliatory, but by perseverance and patience got what he wanted. He dressed as an Ethiopian dedicated to study, a "memhir". He walked barefoot, for only lepers and Jews wore sandals. He worked assiduously to integrate and soon was called "the man of the book";

Arnaud was more flamboyant, and stood out. He forged ties to princes and warlords, participated in battles and came close to death many times. He was above all the friend and confidant of Dejazmach Goshu, prince of Gojjam, who considered him his son. Arnaud was known as "ras Michael".

In 1987 the historian, jurist, linguist and high Ethiopian official Berhanou Abebe published verses, distiches from the Era of Princes which refer to Arnaud ("ras Michael"): "I have not even provisions to offer them, / Let the earth devour me in the place of the men of ras Michael. / Is it an oversight of the embosser or the lack of bronze / That the scabbard of Michael's saber has no ornamentation?.[8]

For tactical reasons Arnaud and Antoine travelled separately. They spent little time together but kept in touch. They united for the Ennarea expedition to the kingdom of Kaffa in search of the source of the White Nile.

In general Arnaud prepared the ground for Antoine, making the first visits and approaches to the local lords. Antoine then quietly gathered valuable information on the geography, geology, archeology and natural history of Ethiopia.

1837-1839

Antoine d'Abbadie arrived in Egypt around October 16, 1837, and joined his brother Arnaud, already in Cairo. They stayed about two months and became friends with Giuseppe Sapeto,[9] a Lazarist father, and an English explorer named Richards. In December 1837 the two brothers and Father Sapeto left for Massawa, the port of entry to Abyssinia.

.png.webp)

When they arrived in Massawa, rumor said that Dejazmach Wube, governor of Tigray, the first region they needed to cross, had massacred a Protestant mission and prohibited all Europeans from entering the territory on pain of death. Richards returned to Cairo. Arnaud and Father Sapeto went to Adwa to speak directly with Dejazmach Wube. Antoine stayed in Massawa with their luggage.

The rumor was false. The Protestants had not been massacred but imprisoned and expelled from Tigray for not sufficiently respecting the rites of the Ethiopian church and the Marian devotions. Arnaud used his diplomatic talent with Dejazmach Wube, who allowed Father Sapeto to stay in Adwa. He and Antoine crossed Tigray without incident. They arrived in Gondar on May 28, 1838. Antoine realized that his instruments were not suitable for precision work and returned to France to obtain adequate instruments. He embarked at Massawa in July 1838 and returned twenty months later in February 1840.

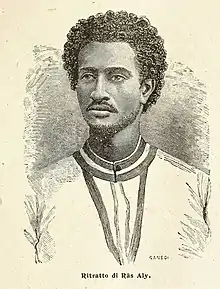

In Gondar, Lik Atskou, a learned high dignitary, took Arnaud under his protection and presented him to Ali, ras of Begemder, who was the same age as Arnaud and had the same sporting passions; they become friends. Ali's mother, Menen Liben Amede, Ali's former regent, was a very powerful woman and she too accepted Arnaud.[10]

Arnaud acquired a reputation as a doctor and diviner and important people showed him friendship. Sahle Selassie, prince of Shewa, the richest province of Abyssinia, promised him help travel in Ennarea, where the brothers Abbadie expected to find the source of the white Nile. Dejazmach Goshu, prince of Gojjam under the suzerainty of Ras Ali, became Arnaud's closest friend in Abyssinia. He sent one of his sons, Lij Dori, to Gondar to be treated by Arnaud, with an invitation to come to Gojjam. Since he had to go through Gojjam to enter Ennarea, Arnaud accepted and travelled south towards Dambatch with Lij Dori and his troops. On this journey Arnaud witnessed his first battle. A warlord tried to kidnap Lidj Dori, the better to negotiate a deal with Dejazmach Goshu. Arnaud also visited the "Eye of Abay" the source of the Blue Nile.

Dejazmach Goshu and his wife Waizero Sahalu accepted Arnaud as an adopted son. He took part in a campaign against the Oromos and dressed as an Ethiopian soldier. On the death of Dejazmach Kenfu, governor of Dembiya under subservient to Ras Ali, a war of succession broke out. Ras Ali allied with Dejazmach Goshu and his son Birru against the sons of Dejazmach Kenfu. Arnaud took part in the Battle of Konzula on October 4, 1839. Kenfu's sons were taken prisoner.[11]

1840-1842

Antoine d'Abbadie arrived in Massawa with his new geodesy instruments in February 1840. The brothers left for Adwa on February 12 intending to return to Gondar, where Antoine would do geodetic surveys for several months, while Arnaud went to Gojjam, the court of Dejazmach Goshu. Then together they would cross the country of the Oromos to reach the kingdom of Ennarea, where they thought they would find the source of the White Nile.[12]

They first needed to cross the Tigray, but its governor, the Dejazmach Wube, was very aggressive towards them. During their courtesy visit, Arnaud annoyed Wube who, under the effect of mead, threatened to cut off his tongue and a hand and a foot. Arnaud had the choice between using his weapon, or accepting the punishment to save his brother's life. His courage impressed Wube, who reconsidered. He ordered Arnaud and Antoine to leave his territory immediately, and never return.[13]

In Adwa, the brothers separated; Arnaud, defying the prohibition of Dejazmach Wube, remained in Adwa with his horse, which was ailing; Antoine left for Massawa with the luggage and the servants. Antoine traveled the Massawa region for several months, using his new instruments. In a hunting accident shrapnel from a cartridge injured his eye. He left for Aden to find a doctor. Arnaud traveled to Digsa, where he bonded with Bahar Negach. During this period, Arnaud increased his reputation by rescuing several Christian women sold as slaves. When Arnaud received news of his brother's accident, he left for Aden. Unable to keep his horse, he sent it to the Prince of Joinville, who had helped Antoine obtain his geodesy instruments.[14]

The trip to Aden was complicated, as the region was under English rule and Captain Haines believed that Arnaud and Antoine were spying for France. When Arnaud arrived in Aden, Antoine had already left for Cairo for treatment, but had left a message: they could try to reach the kingdom of Ennarea from the south, via Berbera, the region of Harar and the Shewa, or Prince Sahle Selassie would protect them.

In Berbera the local potentates, under the influence of the English, blocked them. Antoine and Arnaud could not travel within the country. During their forced stay, they deepened their knowledge of languages, habits and customs; Antoine collected manuscripts and prepared a dictionary. On January 15, 1841, they left Berbara, made too inhospitable by Captain Haines, for the port of Tadjoura. Their plan was still to reach the kingdom of Ennarea from the south.

After three months of attempted negotiations, faced with pressure from Captain Haines, they abandoned the project and on May 12, 1841, left Djibouti for Yemen. As Christians the brothers were not well-received.[15] Antoine returned to Massawa. Arnaud left on a mission to Jeddah then joined Antoine in August 1841. They were still trying to cross the Tigray. Arnaud left alone for Adwa. He stopped at Digsa and against all advice, visited the Dejazmach Wube. The political situation had changed. Wube was waging war against Ras Ali and allied with Dejazmach Goshu. Arnaud was received with great fanfare by Dejazmach Wube.

1842-1844

Thanks to Dejazmach Wube's changed alliances, Arnaud could cross Tigray to go to Gojjam and Antoine could stay in Tigray and travel freely. He arrived in Adwa on January 2, 1842, and spent several months making geodetic measurements. Then Dejazmach Wube was taken prisoner in a battle and the territory was in turmoil. Antoine was forced to find refuge for several weeks in a church in Adwa, then escaped and went to Gondar.

There he studied languages, collected manuscripts and made geodesic triangulations (850 absolute landmarks for cartography). Towards the end of September he visited Lake Tana and in January–February the churches of Lalibela. and left Gondar in February 1843 for Gojjam.

Arnaud, after leaving the Dejazmach Wube, went to Gondar where he learned of the victory of Ras Ali at the Battle of Dabra Tabor on February 13, 1842. He renewed his contacts with Lik Atskou, Waizoro Mannan and the Abuna. In August 1842 he left Gondar to join Dejazmach Goshu and his wife Woizero Sahalu near Dorokoa. He also renewed his relations with Birru, the illegitimate son of Goshu, who was encamped with his army in the vicinity. Arnaud was totally involved in military life with Goshu and Birru.

In February 1843 the armies of Goshu and Birru met to fight Ras Ali. Antoine arrived on February 27. He was tasked by the Abuna of Aksoum with mediating the dispute between Ras Ali and Dejazmach Goshu. Despite Arnaud's intercession, the mission failed.

Antoine wanted Arnaud to go with him to Ennarea in search of the source of the White Nile, but given the military situation, Arnaud decided that he must stay with the Dejazmach Goshu. He believed that Goshu's influence over the Oromo tribes could protect his brother on this dangerous expedition. So Antoine left alone on May 19, 1843 for Mota.

The campaign against Ras Ali began. The two armies fought in Wello until the end of June 1843. Arnaud was with Birru. The latter appreciated his qualities and forced him to stay by his side. He also wanted to separate Arnaud and Goshu, as he intended to take his father's place. Arnaud and other devotees of Goshu tried to leave the camp of Birru in October 1843 and go to the city of Mota, then join the camp of Goshu.

At the beginning of 1844 he finally received news from his brother: Antoine was a captive in Oromo country, with Abba Bagibo, Prince of Ennarea. Antoine, who had left with a caravan in May 1843, arrived in Saka in the kingdom of Limmu-Ennarea, on July 26. He was received in audience by King Abba Bagibo. The latter suspected Antoine, the first white man he had seen, of supernatural knowledge, and kept him at his court.

The King of Kaffa wanted to see the white man and asked Abba Bagibo to send him. In exchange, he accepted an alliance that Bagibo had wanted for a long time. Antoine was sent by Abba Bagibo as a "marriage brother" to arrange the marriage of a king's daughter to Abba Bagibo. He was the first European to visit the Kaffa. He stayed 14 days in Bonga, then returned with Abba Bagibo on December 19, 1843. He feared he would never be able to return to Gojjam.

Arnaud threatened to use his army to prevent all caravans from entering the country of Abba Bagibo if his brother was not freed. On February 25, 1844, Antoine left Ennarea with a caravan and returned to Gojjam on April 10, 1844. He visited the source of the Abaïe and made geodetic measurements, then went to Baguina, to the Agew. He returned to Gondar on July 30, 1844.

Meanwhile Dejazmach Goshu was taken prisoner by Dejazmach Syoum. Birru was plotting against his father. Vassals loyal to the Goshu were relieved of their responsibilities. Birru insisted on keeping Arnaud with him, promising him honors and territories if he accepted his suzerainty. Birru didn't want to let Arnaud go to Ras Ali to negotiate his father's release because he was afraid Arnaud would succeed.

Arnaud remained faithful to his friend Goshu and, dodging Birru's troops, arrived at Debre Tabor around May 15, 1844. He wanted to negotiate the release of Goshu with Ras Ali.

Ras Ali received "Michael" with honors and Arnaud convinced him that the best political solution was to free Goshu. The problem was that Goshu was held back by Ali's mother, who had a strained relationship with her son. So Arnaud left for Gondar to negotiate directly with her. Arnaud was helped by Atse Yohannes (second husband of Menen Liben Amede).

Menen's grievance against Goshu was simply that he was Birru's father. The quarrel between Ali and Birru was irreconcilable and Birru's wife, Oubdar, was Menen's favorite daughter. She hated her son-in-law and wanted her daughter back, so she offered to trade her for Goshu's release. Birru, who secretly did not want his father's release, disrupted the negotiations in April 1844.

Thanks to Arnaud, Lik Atskou and Ali the second attempt to negotiate was a success: Goshu was brought to Gondar, Menen forgave him and he was released. Goshu and Arnaud left for Debre Tabor to seal the reconciliation with Ras Ali.

Alliances changed again: Goshu and Syoum, under the suzerainty of Ali, allied against Birru and Wube. Birru increased his army to 50,000 men. Factional warfare ensued, and as is often the case, consisted of many battles with no winner or loser.

Arnaud returned to Gondar in July 1844 and was joined by Antoine on July 30. The latter left for Massawa on September 25 and returned around December 20. Meeting in Gondar, the two brothers analyzed the information in their possession on the possible source of the White Nile. They believed that the Gibe, flowed into the Omo, which was, in the opinion of Joseph-Pons d'Arnaud, the main tributary of the White Nile. Despite the dangers they planned a second trip to Ennaréa, to determine the source of the Gibe.

1844-1846

The two brothers left Gondar on February 18, 1845. Antoine left for Kouarato, on his way to the kingdom of Enarea, and Arnaud for the hot springs of Gur Amba, where he met Walter Plowden,[16] an English explorer, who left his companion John Bell (future advisor to Tewodros II) at Mahadera Mariam. One of Arnaud's men injured a native, which posed a problem. There was a threat of a trial, with very serious consequences for Arnaud if the man died. To avoid danger, Arnaud and Plowden immediately left for Kouarata near Lake Tana to join Antoine, Goshu and Ali. They arrived on March 8, 1845.

To increase his military power, Goshu went on tour with Arnaud to recruit deserters from Birru. They returned to Kouarata on April 8, 1845. Antoine left with Ras Ali to go to Gojjam, because it took an escort of armed troops to cross the country, held by various factions opposed to Ali and Goshu. Antoine left Ali on April 14, 1845, and traveled south alone. He crossed Abaye again and arrived unescorted in the kingdom of Jimma in June. Ten days later, he crossed into the kingdom of Limma-Enarea and began to collect information on the rivers and their sources. He ended up recognizing in the Gibé the main tributary of the Omo and therefore of the White Nile. The source was in the Ababya forest north of Jimma.

The internal war between Ali, Goshu, Birru, Wube was in full swing. Arnaud participated very actively, and was so appreciated by Goshu that he offered to entrust him with the command of his armies. At the same time, Antoine called on him to leave Goshu and come to Ennarea to seek the source of the White Nile. Arnaud was torn between Goshu and his brother but in the end told Goshu that he must join his brother, but would come back after their expedition. Sadly, Goshu gave his blessing. Arnaud also needed Ali's authorization to join Antoine, however, and Ali categorically refused. Arnaud was too useful as a soldier. Arnaud managed to convince Ali that if he entrusted him with a diplomatic mission to the prince of Enarea, Abba Bagibo, the result would benefit Ali. The mission would also protect Arnaud against mistreatment by Abba Bagibo.

Arnaud left with a caravan travelling towards Ennarea. On the way he met Plowden and Bell, and together they crossed the Blue Nile to arrive in Oromo country. The two Englishmen carried rifles, but Arnaud advised them to get rid of all their firearms, because they provoked the covetousness of the Oromos, who would not hesitate to kill to obtain them, and if Plowden or Bell killed a Oromo, all Europeans in the vicinity would be massacred. After the crossing, Arnaud and the English separated, each with their Oromo protector; Arnaud's was Choumi, a Oromo notable. Arnauld arrived in the village of Choumi on July 8, 1845.Plowden did not follow Arnaud's advice and a few days later, during a confrontation with a band of Oromos, he killed a man. In consequence Oromo armed bands wanted to massacre all Europeans on their territory. The road to Ennarea was now blocked for Arnauld.

Stuck at Choumi, Arnaud could not return to Gojjam. He took advantage of this period of inactivity to learn the Galla languages. In the villages, Arnaud used his knowledge of customs and psychology to practice geomancy. He made.an impression and had a reputation as a diviner. On August 25, Arnaud received news from Antoine, who was at Abba Bagibo's. The latter wanted Arnaud to come to him. Antoine said that the road might be passible although very dangerous. Arnauld left with six men and crossed hostile countries. On December 10, Arnaud crossed the Gibé and arrived safe in the kingdom of Limmou-Enaréa. He reached Antoine in Saqqa, the main town of Ennarea, on December 15, 1845.

Arnaud and Antoine had an audience with Abba Bagibo on December 20, 1845, and asked permission to go to the source of the Gibé, under the pretext of making an offering to a local god. Abba Bagibo, a recent convert to Islam, also kept ancestral beliefs and granted their request.The two brothers left Saqqa on January 15 and arrived at the source on January 19, 1846.

Antoine and Arnaud were retained as "guests" by Abba Bagibo. He wanted to use Arnaud's "divinatory gift" for his own ends. Escape was almost impossible, and it would be necessary to kill several guards and cross deserts to avoid armed gangs. Arnaud planned to hide his brother in a caravan leaving the country, then escape himself and cross Ennarea and the Oromo country alone. But before he put the plan into execution, a whim of Abba Bagibo opened a way out: Abba Bagibo wanted a relative of Ras Ali as his wife and tasked Arnaud with negotiating for her. The two brothers left Saqqa with all honors.

The return route was strewn with difficulties and quarrels between tribes; they were repeatedly threatened with death. They were forced to separate and only reunited in December 1846.

1847-1849

Arnaud and Antoine arrived in Gondar on April 20, 1847, along the eastern coast of Lake Tana. They learned that their younger brother, Charles was in Massawa looking for them. Their mother had had no news of them for almost twelve years, and was worried; she sought advice and help from the Vatican and the Viceroy of Egypt, then sent her third son to Ethiopia.[17]

Antoine explored Agame and in 1848 Semien Gondar where he climbed Ras Dashen, the highest point in Ethiopia and the Simien Mountains. His elevation measurement (4,600 meters; 15,100 ft) was very close to the modern estimate (4,550 meters; 14,930 ft).

Antoine's chronic ophthalmia rendered him blind and he was forced to leave Abyssinia for good. On October 4, 1848, Antoine left Massawa and arrived in Cairo on November 3. Arnaud and Charles left Massawa at the end of November. The three brothers returned to France at the beginning of 1849.

Sources of the Nile

Since ancient times it had been known that the Nile results from the confluence of two rivers near Khartoum in Sudan, the Blue Nile and the White Nile. The source of these two rivers remained a mystery until the eighteenth century. The goal of the brothers was to find the source of the White Nile, which some geographers (especially Joseph-Pons d'Arnaud) believed to be in the kingdom of Kaffa.

Blue Nile

Carte interactive

Carte interactive

The source of the Blue Nile had been found by the Portuguese monk Pedro Páez[18][19] in 1618 and visited by the Scottish explorer James Bruce in 1770. The river rises near Gish Abay, 100 kilometers (62 mi) southwest of Lake Tana, crosses the lake with a noticeable current (as the Rhône crosses Lake Geneva), then exits at Baher Dar and makes a long loop towards Khartoum.

In 1840-1841, Arnaud was in the vicinity of the spring with troops of Lidj Dori and took the time to visit it. He was the third European to do so. He gave a rather brief description on his book.[20] Arnauld gave little importance to the precise, more or less arbitrary, name of the source of a river with multiple tributaries: "But I leave these questions, those which flow from them, and the theories which give rise to them, to those for whom they contain a first-rate interest; what mattered most to me in my visit to the famous springs of Abbaïe was the study of the populations that had to be crossed to reach them" In June–July 1844, Antoine was with the army of Dejazmach Birru, the son of Dejazmach Goshu, who wanted to subdue two provinces near the source. Naturally, Antoine wanted to be the fifth European to visit "the Eye of Abbaia" (the English explorer mentioned by Antoine in his account is probably Charles Beke, who followed the course of the Blue Nile from Khartoum). Birru gave him an escort of fifteen spears to protect him in that hostile country. Antoine wrote a detailed description of the source and geographical measurements he made.[21]

White Nile

There remained the White Nile and its source. In April 1844, Antoine published his ideas and observations on the possible tributaries of the White Nile.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Antoine and Arnaud d'Abbadie believed that the Omo River was the main tributary of the White Nile. Because the Ghibie River was the main tributary of the Omo, they consideref the source of the Ghibie to be the source of the White Nile. After suffering many difficulties and dangers, on January 15, 1846, the two brothers arrived at the source of the Ghibie in the Babya forest north of Jimma. They planted the French flag and drank to the health of King Louis-Philippe I.[29] The coordinates of the source are: 7° 56' 37.68" N, 36° 54' 183 E28.[30]

Unfortunately, their basic assumption was wrong: the Omo is not a tributary of the White Nile.

As soon as Antoine announced the discovery[31][32] his assertion was contested, notably by the English explorer Charles Beke.[33] Antoine d'Abbadie retaliated as soon as he became aware of Beke's communication.[34][35]

The published correspondence between Antoine d'Abbadie and Charles Beke is very hushed, but vitriolic. Beke analyzed Antony's observations in detail and indicated a number of plausible errors or inconsistencies. But the situation between the two men was such that Beke openly saif that he believed that Antoine d'Abbadie never went to the kingdom of Kaffa invented everything. In protest, Beke returned the gold medal,[36] awarded to him by the Geographical Society in 1846, for his exploration of the Blue Nile.[37]

1850-1893

On 26 July 1850 Antoine and Arnaud d'Abbadie d'Arrast received the gold medal of the Société de Géographie.[38] On September 27, 1850, the two brothers were made knights of the Legion of Honor.[39]

Ambitions for Ethiopia

The trip to Ethiopia made a strong impression on Arnaud who became attached to this country. "The plateaus of upper Ethiopia, which were difficult for us to reach, became to me like a promised land. The oath that bound me to Dedjadj Birro encouraged me to make new efforts and, with the energy and self-sacrifice of our age, we decided to brave everything rather than give up our enterprise."[40]

He had only one idea in mind: to make his friend the Dejazmach Goshu the new emperor of Ethiopia and link their two countries:

"I would like us to leave this land of Damot. I would like victory to remain on our side in a happy fight against Ali. I would like My lord (Dejazmach Goshu) to be seated in Ali's seat, and I would like to hear an order issued in his name that restored to the original possessors all the lands of Ethiopia.

I would also have liked our weapons to have been used to sweep from this land to the tip of the earth all traces of our Muslim invaders. I would like to see them pushed back into the Wollo, even beyond. I would like to see My lord send messages to Dejazmach Wube to summon this prince to come, to recognize our suzerainty. From there, I would like to govern to the shores of the Red Sea. So, after a few months, the waves would bring us half a dozen engineers from my country with weapons and cannons. These men would serve us to establish at the center of our conquests a great stronghold which, though sitting, in the middle of a plain, would be stronger than the Steepest hillforts.

I would like to reconquer all these neighboring lands of Gojjam that the pagan Gallas (Oromos) have torn from the Christian races. For them, I would like to send them an inflexible master who would send them priests to teach them our religion. A few years of fortune and all these things would be possible... Like the emperors of Ethiopia and better than them, we would enter into friendly relations with the sovereigns of Egypt, the chiefs of Arabia and those of Europe."[41]

Return to Ethiopia

Arnaud returned to France on a mission. He wanted to complete his project of a Christian empire of Ethiopia with Dejazmach Goshu as emperor, under the protection of France. He addressed his report to the government through the Duke of Bassano. The latter responded favourably and, without an official mission, Arnaud was instructed to bring diplomatic gifts to Goshu on behalf of France, intended to promote an alliance. Arnaud's mother made him promise not to cross the Tekezé, a sub-tributary of the Black Nile on the western border of Tigray. She wanted him to stay where he could easily reach the sea to return to France.

As soon as he landed in Massawa, the news of the return of "Ras Michael" spread; the Dejazmach Goshu was looking forward to seeing his friend again. Unfortunately, Goshu was on the other side of the river in the Gojjam. Arnaud kept his promise and was unable to join Goshu. They exchanged many letters, but Arnaud remained faithful to his oath.

In November 1852, the Battle of Gur Amba ended with the death of Dejazmach Goshu and the victory of Kassa Hailou, the future Tewodros II.

For Arnaud, it was a disaster; he had lost a very dear friend. His hope of building a Christian empire vanished with him. Desperate, he returned to France at the end of December 1852.

His last attempt to link France and Ethiopia was in 1863. The British were omnipresent in the region (Sudan, Aden, Somalia) and aimed to take Ethiopia under their protection. The Negus was prepared to resist the British offer if France sent him military aid. Arnaud asked Napoleon III for an audience to explain the advantages to be expected for the France. The emperor listened politely, but for reasons of alliances signed with England, refused to intervene. In 1868 the British expedition to Ethiopia put Ethiopia under the protection of the British Empire.

Arnaud travelled relatively little after 1853. He did, however, go to Jerusalem where he wanted to found, at his own expense, an asylum for Ethiopian pilgrims.

Second marriage and children

Arnaud married an American, Elisabeth West Young; she was the daughter of Robert West Young (1805–1880), a physician and Anne Porter Webb.

They had nine children:[42]

- Anne Elisabeth (1865-1918) ;

- Michel Robert (1866-1900) ;

- Thérèse (1867-1945) ;

Ciboure - château d'Elhorriaga

Ciboure - château d'Elhorriaga - Ferdinand Guilhem (1870-1915)

- Marie-Angèle (1871-1955) ;

- Camille Arnauld (1873-1968) ;

- Jéhan Augustin (1874-1912) ;

- Martial (1878-1914) ;

- Marc Antoine (1883-1914).

His salon, rue de Grenelle, was a regular appointment for intelligent and educated men, but Arnauld hated worldliness and he left Paris with his family to return to the Basque Country. He built the castle of Elhorriaga in Ciboure, designed by the architect Lucien Cottet. The castle was occupied by the Wehrmacht during the Second World War and was destroyed in 1985 to make way for a real estate project.[43]

Life in Ciboure and death

.jpg.webp)

In Ciboure he quickly gained a reputation as a charitable man, but always remained discreet. The first volume of the account of travels in Ethiopia was published by Arnauld in 1868 under the title Twelve years of stay in Upper Ethiopia. It recounts the period 1837-1841. The next three volumes were not published during his lifetime. Volume 1 was translated for the first time in 2016 into the Ethiopian language and Volume 2 in 2020 under the title "በኢትዮጵያ ከፍተኛ ተራሮች ቆይታዬ" (My stay in the high mountains of Ethiopia).

Arnaud did not forget his patriotism and in 1870 he tried to form a free company and lead it to defeat the invasion. His call was heard and the company was about to leave when the armistice was signed on January 28, 1871.

At the time of the decrees expelling the congregations in 1880, Arnauld put his house, located a few kilometers from the Spanish border, at the service of the victims of these sectarian laws. The Fathers of the Society of Jesus were, above all, his guests.

Arnaud died on 8 November 1893; he is buried in the cemetery of Ciboure. The photograph in Ethiopian clothes was taken shortly before his death.

The memory of "Ras Michael" remained alive in Ethiopia for a long time, indeed Emperor Menelik II and his wife referred to him:

[…] "He had, in her person, made to love the France. And if we have sympathies among this people today, the old men and Menelik himself will tell you the reason: "We have not forgotten Ras Michael..."[44]"..

References

- Thorne 1984, p. 1

- Goyhenetche, Manex. Antoine d'Abbadie intermédiaire social et culturel du Pays Basque du XIXe siècle? (PDF).

- Les voyageurs français et les relations entre la France et l'Abyssinie de 1835 à 1870. Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire. p. 151.

- "Annonces judiciaires". Gallica. Le Moniteur des Pyrénées: 4. April 11, 1883.

- d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 2.

- Darboux, Gaston (1908). "Notice Historique sur Antoine d'Abbadie". Gallica. Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France: 35-103.

- Bernoville, Gaëtan (May 1950). L'épopée missionnaire d'Éthiopie: Monseigneur Jarosseau et la mission de Gallas. Paris: Albin Michel.

- Abebe, Berhanou (1987). "Distiques du Zamana asafent", Annales d'Éthiopie. p. 32-33.

- Pankhurst, Richard. "Sapeto, Giuseppe (1811-1895)". Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

- Prouty Rosenfeld, Chris (1979). ""Eight Ethiopian women of the "Zemene mesafint" (c. 1769-1855) "". Northeast African Studies. 1 (2): 72-79. JSTOR 43660013.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 445.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 432.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 526-533.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 557.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1980). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Vol. 2. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. p. 2.

- " Walter Plowden, Travels in Abyssinia and the Galla country: with an account of a mission to Ras Ali in 1848 ". London, Longmans, Green & Co. 1868. p. 160-164.

- d'Arnaud, Joseph (1847). " Nouvelles de MM. Antoine et Arnauld d'Abbadie". Bulletin de la Société géographique vol. 7. p. 273-275.

- Beke, Charles (March 1848). Mémoire justificatif en réhabilitation des pères Pierre Paëz et Jérôme Lobo, missionnaires en Abyssinie, en ce qui concerne leurs visites à la source de l'Abaï (le Nil) et à la cataracte d'Alata (I). Bulletin de la Société géographique\. p. 145-186.

- Beke, Charles (March 1848). Mémoire justificatif en réhabilitation des pères Pierre Paëz et Jérôme Lobo, missionnaires en Abyssinie, en ce qui concerne leurs visites à la source de l'Abaï (le Nil) et à la cataracte d'Alata. Vol. 2. Bulletin de la Société géographique. p. 209-239.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 229-231.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Le Bahr-el-Azrak ou le Nil-Bleu. Vol. 3. Bulletin de la Société géographique.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Fragment d'une lettre sur le Nil-Blanc, et sur les principales rivières qui concourent à le former (avril 1844). Vol. 3. Bulletin de la Société géographique. p. 311-319.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Source du Nil blanc. Vol. 1. Nouvelles annales des voyages. p. 365-366.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Lettres de l'Abyssinie. Vol. 2. Nouvelles annales des voyages. p. 107-122.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Lettres de l'Abyssinie. Vol. 2. Nouvelles annales des voyages. p. 218-226.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1845). Lettre Omokoullou - 3 novembre 1844. Vol. 3. Nouvelles annales des voyages. p. 83-101.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1846). Sources du Nil. Vol. 11. Revue d'Orient. p. 73-83.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1846). Voyage au royaume d'Enarya. Vol. 11. Revue d'Orient. p. 197-201.

- Jacobs, Alfred (October 15, 1856). Les voyages d'exploration en Afrique: les sources du Nil et l'Afrique équatoriale. Vol. 5. Revue des Deux Mondes. p. 894-896.

- "Une image satellite de la source". Google Maps.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1847). Lettre adressée à M. Jomard (6 août 1847). Vol. 8. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie. p. 94-97.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (October 5, 1847). Lettre adressée à M. Jomard (6 août 1847). Journal des débats politiques et littéraires. p. 2-3.

- Beke, Charles (1847). Lettre de M. Beke adressée au président de la Société de Géographie. Vol. 8. Bulletin de la Société géographique. p. 356-361.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1849). Note sur le haut Fleuve Blanc. Vol. 12. Bulletin de la Société de géographie. p. 144-161.

- d'Abbadie, Antoine (1852). Nouvelles du haut fleuve blanc. Vol. 3. Bulletin de la Société de géographie. p. 340-356.

- de Rochelle, Roux (1846). Rapport sur le concours au prix annuel pour la découverte la plus importante en géographie. Vol. 5. Bulletin de la Société de géographie. p. 291-299.

- Returning the gold medal of the geographic society of France. Bulletin de la Société de géographie. 1851. p. 1-5.

- Daussay, P (1850). "Rapport de la Commission du concours au prix annuel pour la découverte la plus importante en géographie". Vol. 14. Bulletin de la Société de Géographie. p. 10-28.

- Dumas, J (October 4, 1850). Rapport au Président de la république: Légion d'honneur. Journal des débats politiques et littéraires.

- d'Abbadie, Arnaud (1868). Douze ans de séjour dans la Haute-Éthiopie. Hachette. p. 607.

- d'Henriaur, M. (January 23, 1932). Les souhaits d'un Français à un prince Éthiopien il y a cent ans. Le Figaro. p. 6-7.

- Arbre genéologique d'Arnauld d'Abbadie. Geneanet.

- Une vigie de l'histoire. Sud-Ouest.

- d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 1-16.

Bibliography

- Nicaise, Auguste (1868). Compte rendu : Douze ans dans la Haute Éthiopie (Abyssinie) (in French). Bulletin de la Société géographique. p. 389-398.

- d'Arnély, G. (1898). Arnauld d'Abbadie, explorateur de l'Ethiopie (1815-1893) (PDF) (in French). Les Contemporains. p. 1-16.

- Morié, Louis J. (1904). Histoire de l'Éthiopie (Nubie et Abyssinie) depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à nos jours (in French). Paris: A. Challamel. p. 500.

- Pérès, Jacques-Noël (2012). Arnauld d'Abbadie d'Arrast et le voyage aux sources du Nil (in French). Transversalités. p. 29-42.

- Perret, Michel (1986). Villes impériales, villes princières : note sur le caractère des villes dans l'Éthiopie du XVIIIe siècle (in French). Vol. 56. Journal des Africanistes. p. 55-65.

- Tubiana, Joseph. "Les moissons du voyageur ou l'aventure scientifique des frères d'Abbadie (1838-1848)". Euskonews & Média (in French).

- Crummey, Donald (2000). Land and Society in the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia. James Currey Publisher. p. 373. ISBN 9780852557631.

- Blundell, Herbert Weld (1922). The Royal chronicle of Abyssinia, 1769-1840. London: Cambridge: University Press. p. 384-390.

- Ficquet, Éloi (2010). "La mixité religieuse comme stratégie politique. La dynastie des Māmmadoč du Wallo (Éthiopie centrale), du milieu du XVIIIe siècle au début du XXe siècle". Open Edition Journals : Afriques (in French).

- Ficquet, Éloi (2017). "Notes manuscrites d'Arnauld d'Abbadie sur l'administration des établissements religieux en Éthiopie dans les années 1840-1850". Archive ouverte en Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société (in French).

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbadie, Antoine-Thomson d'; and Abbadie, Arnaud-Michel d'". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak - Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Shahan, Thomas Joseph (1907). "Antoine d'Abbadie". In Herbermann, Charles George; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé Bénoist; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). The Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church. Vol. I: Aachen–Assize. New York, NY: The Encyclopedia Press, Inc. LCCN 30023167.

- Thorne, John, ed. (1984). "Abbadie, Michel Arnaud d'". Chambers Biographical Dictionary (Revised ed.). Chambers. ISBN 0-550-18022-2.