Franco-Prussian War

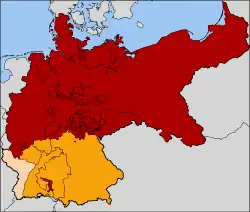

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War,[lower-alpha 2] often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 January 1871, the conflict was caused primarily by France's determination to reassert its dominant position in continental Europe, which appeared in question following the decisive Prussian victory over Austria in 1866.[12] According to some historians, Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck deliberately provoked the French into declaring war on Prussia in order to induce four independent southern German states—Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria and Hesse-Darmstadt—to join the North German Confederation; other historians contend that Bismarck exploited the circumstances as they unfolded. All agree that Bismarck recognized the potential for new German alliances, given the situation as a whole.[13]

| Franco-Prussian War (1870) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the unification of Germany | |||||||

(clockwise from top right)

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Before 18 January 1871:

After 18 January 1871: |

Before 4 September 1870: After 4 September 1870: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total deployment:

Initial strength:

Peak field army strength:

|

Total deployment:

Initial strength:

Peak field army strength:

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

144,642[4]

| |||||||

| |||||||

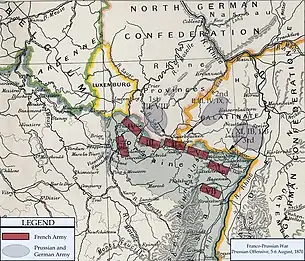

France mobilised its army on 15 July 1870, leading the North German Confederation to respond with its own mobilisation later that day. On 16 July 1870, the French parliament voted to declare war on Prussia; France invaded German territory on 2 August. The German coalition mobilised its troops much more effectively than the French and invaded northeastern France on 4 August. German forces were superior in numbers, training, and leadership and made more effective use of modern technology, particularly railways and artillery.

A series of hard fought Prussian and German victories in eastern France, culminating in the Siege of Metz and the Battle of Sedan, resulted in the capture of the French Emperor Napoleon III and the decisive defeat of the army of the Second Empire; a Government of National Defense was formed in Paris on 4 September and continued the war for another five months. German forces fought and defeated new French armies in northern France, then besieged Paris for over four months before it fell on 28 January 1871, effectively ending the war.

In the waning days of the war, with German victory all but assured, the German states proclaimed their union as the German Empire under the Prussian king Wilhelm I and Chancellor Bismarck. With the notable exceptions of Austria and German Switzerland, the vast majority of German-speakers were united under a nation-state for the first time. Following an armistice with France, the Treaty of Frankfurt was signed on 10 May 1871, giving Germany billions of francs in war indemnity, as well as most of Alsace and parts of Lorraine, which became the Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine (Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen).

The war had a lasting impact on Europe. By hastening German unification, the war significantly altered the balance of power on the continent, with the new German state supplanting France as the dominant European land power. Bismarck maintained great authority in international affairs for two decades, developing a reputation for Realpolitik that raised Germany's global stature and influence. In France, it brought a final end to imperial rule and began the first lasting republican government. Resentment over the French government's handling of the war and its aftermath triggered the Paris Commune, a revolutionary uprising which seized and held power for two months before its bloody suppression; the event would influence the politics and policies of the Third Republic.

Causes

The causes of the Franco-Prussian War are rooted in the events surrounding the gradual march toward the unification of the German states under Otto von Bismarck. France had gained the status of being the dominant power of continental Europe as a result of the Franco-Austrian War of 1859. During the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the Empress Eugénie, Foreign Minister Drouyn de Lhuys and War Minister Jacques Louis Randon were concerned that the power of Prussia might overtake that of France. They unsuccessfully urged Napoleon to mass troops at France's eastern borders while the bulk of the Prussian armies were still engaged in Bohemia as a warning that no territorial changes could be effected in Germany without consulting France.[14] As a result of Prussia's annexation of several German states which had sided with Austria during the war and the formation of the North German Confederation under Prussia's aegis, French public opinion stiffened and now demanded more firmness as well as territorial compensations. As a result, Napoleon demanded from Prussia a return to the French borders of 1814, with the annexation of Luxembourg, most of Saarland, and the Bavarian Palatinate. Bismarck flatly refused what he disdainfully termed France's politique des pourboires ("tipping policy").[15][16] He then communicated Napoleon's written territorial demands to Bavaria and the other southern German states of Württemberg, Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt, which hastened the conclusion of defensive military alliances with these states.[17] France had been strongly opposed to any further alliance of German states, which would have threatened French continental dominance.[18]

The only result of French policy was the consent of Prussia to nominal independence for Saxony, Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Baden, and Hessia-Darmstadt; this was a small victory, and one without appeal to a French public which wanted territory and a French army which wanted revenge.[19] The situation did not suit either France, which unexpectedly found itself next to the militarily powerful Prussian-led North German Confederation, or Prussia, whose foremost objective was to complete the process of uniting the German states under its control. Thus, war between the two powers since 1866 was only a matter of time.

In Prussia, some officials considered a war against France both inevitable and necessary to arouse German nationalism in those states that would allow the unification of a great German empire. This aim was epitomized by Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck's later statement: "I did not doubt that a Franco-German war must take place before the construction of a United Germany could be realised."[20] Bismarck also knew that France should be the aggressor in the conflict to bring the four southern German states to side with Prussia, hence giving Germans numerical superiority.[21] He was convinced that France would not find any allies in her war against Germany for the simple reason that "France, the victor, would be a danger to everybody—Prussia to nobody," and he added, "That is our strong point."[22] Many Germans also viewed the French as the traditional destabilizer of Europe, and sought to weaken France to prevent further breaches of the peace.[23]

The immediate cause of the war was the candidacy of Leopold of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen to the throne of Spain. France feared an encirclement resulting from an alliance between Prussia and Spain. The Hohenzollern prince's candidacy was withdrawn under French diplomatic pressure, but Otto von Bismarck goaded the French into declaring war by releasing an altered summary of the Ems Dispatch, a telegram sent by William I rejecting French demands that Prussia never again support a Hohenzollern candidacy. Bismarck's summary, as mistranslated by the French press Havas, made it sound as if the king had treated the French envoy in a demeaning fashion, which inflamed public opinion in France.[21]

French historians François Roth and Pierre Milza argue that Napoleon III was pressured by a bellicose press and public opinion and thus sought war in response to France's diplomatic failures to obtain any territorial gains following the Austro-Prussian War.[24] Napoleon III believed he would win a conflict with Prussia. Many in his court, such as Empress Eugénie, also wanted a victorious war to resolve growing domestic political problems, restore France as the undisputed leading power in Europe, and ensure the long-term survival of the House of Bonaparte. A national plebiscite held on 8 May 1870, which returned results overwhelmingly in favor of the Emperor's domestic agenda, gave the impression that the regime was politically popular and in a position to confront Prussia. Within days of the plebiscite, France's pacifist Foreign Minister Napoléon, comte Daru, was replaced by Agenor, duc de Gramont, a fierce opponent of Prussia who, as French Ambassador to Austria in 1866, had advocated an Austro-French military alliance against Prussia. Napoleon III's worsening health problems made him less and less capable of reining in Empress Eugénie, Gramont and the other members of the war party, known collectively as the "mameluks". For Bismarck, the nomination of Gramont was seen as "a highly bellicose symptom".[25]

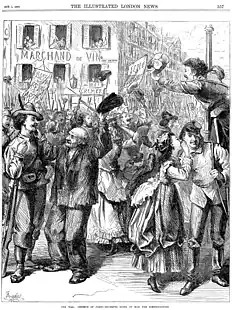

The Ems telegram of 13 July 1870 had exactly the effect on French public opinion that Bismarck had intended. "This text produced the effect of a red flag on the Gallic bull", Bismarck later wrote. Gramont, the French foreign minister, declared that he felt "he had just received a slap". The leader of the monarchists in Parliament, Adolphe Thiers, spoke for moderation, arguing that France had won the diplomatic battle and there was no reason for war, but he was drowned out by cries that he was a traitor and a Prussian. Napoleon's new prime minister, Emile Ollivier, declared that France had done all that it could humanly and honorably do to prevent the war, and that he accepted the responsibility "with a light heart". A crowd of 15,000–20,000 people, carrying flags and patriotic banners, marched through the streets of Paris, demanding war. French mobilization was ordered early on 15 July.[26] Upon receiving news of the French mobilization, the North German Confederation mobilized on the night of 15–16 July, while Bavaria and Baden did likewise on 16 July and Württemberg on 17 July.[27] On 19 July 1870, the French sent a declaration of war to the Prussian government.[28] The southern German states immediately sided with Prussia.[21]

Napoleonic France had no documented alliance with other powers and entered the war virtually without allies. The calculation was for a victorious offensive, which, as the French Foreign Minister Gramont stated, was "the only way for France to lure the wary Austrians, Italians and Danes into the French alliance".[29] The involvement of Russia on the side of France was not considered by her at all, since Russia made the lifting of restrictions on its naval construction on the Black Sea imposed on Russia by the Treaty of Paris following the Crimean War a precondition for the union. But Imperial France was not ready to do this. "Bonaparte did not dare to encroach on the Paris Treaty: the worse things turned out in the present, the more precious the heritage of the past became".[30]

Opposing forces

French

The French Army consisted in peacetime of approximately 426,000 soldiers, some of them regulars, others conscripts who until March 1869 were selected by ballot and served for the comparatively long period of seven years. Some of them were veterans of previous French campaigns in the Crimean War, Algeria, the Franco-Austrian War in Italy, and in the Mexican campaign. However, following the "Seven Weeks War" between Prussia and Austria four years earlier, it had been calculated that, with commitments in Algeria and elsewhere, the French Army could field only 288,000 men to face the Prussian Army, when potentially 1,000,000 would be required.[31] Under Marshal Adolphe Niel, urgent reforms were made. Universal conscription and a shorter period of service gave increased numbers of reservists, who would swell the army to a planned strength of 800,000 on mobilisation. Those who for any reason were not conscripted were to be enrolled in the Garde Mobile, a militia with a nominal strength of 400,000. However, the Franco-Prussian War broke out before these reforms could be completely implemented. The mobilisation of reservists was chaotic and resulted in large numbers of stragglers, while the Garde Mobile were generally untrained and often mutinous.[32]

French infantry were equipped with the breech-loading Chassepot rifle, one of the most modern mass-produced firearms in the world at the time, with 1,037,555 available in French inventories. With a rubber ring seal and a smaller bullet, the Chassepot had a maximum effective range of some 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) with a short reloading time.[33] French tactics emphasised the defensive use of the Chassepot rifle in trench-warfare style fighting—the so-called feu de bataillon.[34] The artillery was equipped with rifled, muzzle-loaded La Hitte guns.[35] The army also possessed a precursor to the machine-gun: the mitrailleuse, which could unleash significant, concentrated firepower but nevertheless lacked range and was comparatively immobile, and thus prone to being easily overrun. The mitrailleuse was mounted on an artillery gun carriage and grouped in batteries in a similar fashion to cannon.[33]

The army was nominally led by Napoleon III, with Marshals François Achille Bazaine and Patrice de MacMahon in command of the field armies.[36] However, there was no previously arranged plan of campaign in place. The only campaign plan prepared between 1866 and 1870 was a defensive one.[18]

Prussians/Germans

The German army comprised that of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia, and the South German states drawn in under the secret clause of the preliminary peace of Nikolsburg, 26 July 1866,[37] and formalised in the Treaty of Prague, 23 August 1866.[38]

Recruitment and organisation of the various armies were almost identical, and based on the concept of conscripting annual classes of men who then served in the regular regiments for a fixed term before being moved to the reserves. This process gave a theoretical peace time strength of 382,000 and a wartime strength of about 1,189,000.[39]

German tactics emphasised encirclement battles like Cannae and using artillery offensively whenever possible. Rather than advancing in a column or line formation, Prussian infantry moved in small groups that were harder to target by artillery or French defensive fire.[40] The sheer number of soldiers available made encirclement en masse and destruction of French formations relatively easy.[41]

The army was equipped with the Dreyse needle gun renowned for its use at the Battle of Königgrätz, which was by this time showing the age of its 25-year-old design.[33] The rifle had a range of only 600 m (2,000 ft) and lacked the rubber breech seal that permitted aimed shots.[42] The deficiencies of the needle gun were more than compensated for by the famous Krupp 6-pounder (6 kg despite the gun being called a 6-pounder, the rifling technology enabled guns to fire twice the weight of projectiles in the same calibre) steel breech-loading cannons being issued to Prussian artillery batteries.[43] Firing a contact-detonated shell, the Krupp gun had a longer range and a higher rate of fire than the French bronze muzzle loading cannon, which relied on faulty time fuses.[44]

The Prussian army was controlled by the General Staff, under General Helmuth von Moltke. The Prussian army was unique in Europe for having the only such organisation in existence, whose purpose in peacetime was to prepare the overall war strategy, and in wartime to direct operational movement and organise logistics and communications.[45] The officers of the General Staff were hand-picked from the Prussian Kriegsakademie (War Academy). Moltke embraced new technology, particularly the railroad and telegraph, to coordinate and accelerate mobilisation of large forces.[46]

French Army incursion

Preparations for the offensive

On 28 July 1870 Napoleon III left Paris for Metz and assumed command of the newly titled Army of the Rhine, some 202,448 strong and expected to grow as the French mobilization progressed.[47] Marshal MacMahon took command of I Corps (4 infantry divisions) near Wissembourg, Marshal François Canrobert brought VI Corps (4 infantry divisions) to Châlons-sur-Marne in northern France as a reserve and to guard against a Prussian advance through Belgium.[48]

A pre-war plan laid down by the late Marshal Niel called for a strong French offensive from Thionville towards Trier and into the Prussian Rhineland. This plan was discarded in favour of a defensive plan by Generals Charles Frossard and Bartélemy Lebrun, which called for the Army of the Rhine to remain in a defensive posture near the German border and repel any Prussian offensive. As Austria, along with Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden were expected to join in a revenge war against Prussia, I Corps would invade the Bavarian Palatinate and proceed to "free" the four South German states in concert with Austro-Hungarian forces. VI Corps would reinforce either army as needed.[49]

Unfortunately for Frossard's plan, the Prussian army mobilised far more rapidly than expected. The Austro-Hungarians, still reeling after their defeat by Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War, were treading carefully before stating that they would only side with France if the south Germans viewed the French positively. This did not materialize as the four South German states had come to Prussia's aid and were mobilizing their armies against France.[50]

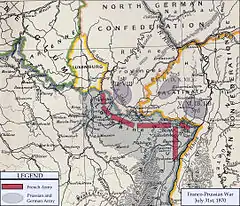

Occupation of Saarbrücken

Napoleon III was under substantial domestic pressure to launch an offensive before the full might of Moltke's forces was mobilized and deployed. Reconnaissance by Frossard's forces had identified only the Prussian 16th Infantry Division guarding the border town of Saarbrücken, right before the entire Army of the Rhine. Accordingly, on 31 July the Army marched forward toward the Saar River to seize Saarbrücken.[51]

General Frossard's II Corps and Marshal Bazaine's III Corps crossed the German border on 2 August, and began to force the Prussian 40th Regiment of the 16th Infantry Division from the town of Saarbrücken with a series of direct attacks. The Chassepot rifle proved its worth against the Dreyse rifle, with French riflemen regularly outdistancing their Prussian counterparts in the skirmishing around Saarbrücken. However the Prussians resisted strongly, and the French suffered 86 casualties to the Prussian 83 casualties. Saarbrücken also proved to be a major obstacle in terms of logistics. Only one railway there led to the German hinterland but could be easily defended by a single force, and the only river systems in the region ran along the border instead of inland.[52] While the French hailed the invasion as the first step towards the Rhineland and later Berlin, General Edmond Le Bœuf and Napoleon III were receiving alarming reports from foreign news sources of Prussian and Bavarian armies massing to the southeast in addition to the forces to the north and northeast.[53]

Moltke had indeed massed three armies in the area—the Prussian First Army with 50,000 men, commanded by General Karl von Steinmetz opposite Saarlouis, the Prussian Second Army with 134,000 men commanded by Prince Friedrich Karl opposite the line Forbach-Spicheren, and the Prussian Third Army with 120,000 men commanded by Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, poised to cross the border at Wissembourg.[54]

Prussian Army advance

Battle of Wissembourg

Upon learning from captured Prussian soldiers and a local area police chief that the Prussian Crown Prince's Third Army was just 30 miles (48 km) north from Saarbrücken near the Rhine river town Wissembourg, General Le Bœuf and Napoleon III decided to retreat to defensive positions. General Frossard, without instructions, hastily withdrew his elements of the Army of the Rhine in Saarbrücken back across the river to Spicheren and Forbach.[55]

Marshal MacMahon, now closest to Wissembourg, spread his four divisions 20 miles (32 km) to react to any Prussian-Bavarian invasion. This organization was due to a lack of supplies, forcing each division to seek out food and forage from the countryside and from the representatives of the army supply arm that was supposed to furnish them with provisions. What made a bad situation much worse was the conduct of General Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot, commander of the 1st Division. He told General Abel Douay, commander of the 2nd Division, on 1 August that "The information I have received makes me suppose that the enemy has no considerable forces very near his advance posts, and has no desire to take the offensive".[56] Two days later, he told MacMahon that he had not found "a single enemy post ... it looks to me as if the menace of the Bavarians is simply bluff". Even though Ducrot shrugged off the possibility of an attack by the Germans, MacMahon tried to warn his other three division commanders, without success.[57]

The first action of the Franco-Prussian War took place on 4 August 1870. This battle saw the unsupported division of General Douay of I Corps, with some attached cavalry, which was posted to watch the border, attacked in overwhelming but uncoordinated fashion by the German 3rd Army. During the day, elements of a Bavarian and two Prussian corps became engaged and were aided by Prussian artillery, which blasted holes in the city defenses. Douay held a very strong position initially, thanks to the accurate long-range rapid fire of the Chassepot rifles, but his force was too thinly stretched to hold it. Douay was killed in the late morning when a caisson of the divisional mitrailleuse battery exploded near him; the encirclement of the town by the Prussians then threatened the French avenue of retreat.[58]

The fighting within the town had become extremely intense, becoming a door to door battle of survival. Despite an unceasing attack from Prussian infantry, the soldiers of the 2nd Division kept to their positions. The people of the town of Wissembourg finally surrendered to the Germans. The French troops who did not surrender retreated westward, leaving behind 1,000 dead and wounded and another 1,000 prisoners and all of their remaining ammunition.[59] The final attack by the Prussian troops also cost c. 1,000 casualties. The German cavalry then failed to pursue the French and lost touch with them. The attackers had an initial superiority of numbers, a broad deployment which made envelopment highly likely but the effectiveness of French Chassepot rifle-fire inflicted costly repulses on infantry attacks, until the French infantry had been extensively bombarded by the Prussian artillery.[60]

Battle of Spicheren

The Battle of Spicheren on 5 August was the second of three critical French defeats. Moltke had originally planned to keep Bazaine's army on the Saar River until he could attack it with the 2nd Army in front and the 1st Army on its left flank, while the 3rd Army closed towards the rear. The aging General von Steinmetz made an overzealous, unplanned move, leading the 1st Army south from his position on the Moselle. He moved straight toward the town of Spicheren, cutting off Prince Frederick Charles from his forward cavalry units in the process.[61]

On the French side, planning after the disaster at Wissembourg had become essential. General Le Bœuf, flushed with anger, was intent upon going on the offensive over the Saar and countering their loss. However, planning for the next encounter was more based upon the reality of unfolding events rather than emotion or pride, as Intendant General Wolff told him and his staff that supply beyond the Saar would be impossible. Therefore, the armies of France would take up a defensive position that would protect against every possible attack point, but also left the armies unable to support each other.[62]

While the French army under General MacMahon engaged the German 3rd Army at the Battle of Wörth, the German 1st Army under Steinmetz finished their advance west from Saarbrücken. A patrol from the German 2nd Army under Prince Friedrich Karl of Prussia spotted decoy fires close and Frossard's army farther off on a distant plateau south of the town of Spicheren, and took this as a sign of Frossard's retreat. Ignoring Moltke's plan again, both German armies attacked Frossard's French 2nd Corps, fortified between Spicheren and Forbach.[63]

The French were unaware of German numerical superiority at the beginning of the battle as the German 2nd Army did not attack all at once. Treating the oncoming attacks as merely skirmishes, Frossard did not request additional support from other units. By the time he realized what kind of a force he was opposing, it was too late. Seriously flawed communications between Frossard and those in reserve under Bazaine slowed down so much that by the time the reserves received orders to move out to Spicheren, German soldiers from the 1st and 2nd armies had charged up the heights.[64] Because the reserves had not arrived, Frossard erroneously believed that he was in grave danger of being outflanked, as German soldiers under General von Glume were spotted in Forbach. Instead of continuing to defend the heights, by the close of battle after dusk he retreated to the south. The German casualties were relatively high due to the advance and the effectiveness of the Chassepot rifle. They were quite startled in the morning when they had found out that their efforts were not in vain—Frossard had abandoned his position on the heights.[65]

Battle of Wörth

The Battle of Wörth began when the two armies clashed again on 6 August near Wörth in the town of Frœschwiller, about 10 miles (16 km) from Wissembourg. The Crown Prince of Prussia's 3rd army had, on the quick reaction of his Chief of Staff General von Blumenthal, drawn reinforcements which brought its strength up to 140,000 troops. The French had been slowly reinforced and their force numbered only 35,000. Although badly outnumbered, the French defended their position just outside Frœschwiller. By afternoon, the Germans had suffered c. 10,500 killed or wounded and the French had lost a similar number of casualties and another c. 9,200 men taken prisoner, a loss of about 50%. The Germans captured Fröschwiller which sat on a hilltop in the centre of the French line. Having lost any hope for victory and facing a massacre, the French army disengaged and retreated in a westerly direction towards Bitche and Saverne, hoping to join French forces on the other side of the Vosges mountains. The German 3rd army did not pursue the French but remained in Alsace and moved slowly south, attacking and destroying the French garrisons in the vicinity.[66]

Battle of Mars-La-Tour

About 160,000 French soldiers were besieged in the fortress of Metz following the defeats on the frontier. A retirement from Metz to link up with French forces at Châlons was ordered on 15 August and spotted by a Prussian cavalry patrol under Major Oskar von Blumenthal. Next day a grossly outnumbered Prussian force of 30,000 men of III Corps (of the 2nd Army) under General Constantin von Alvensleben, found the French Army near Vionville, east of Mars-la-Tour.[67]

Despite odds of four to one, the III Corps launched a risky attack. The French were routed and the III Corps captured Vionville, blocking any further escape attempts to the west. Once blocked from retreat, the French in the fortress of Metz had no choice but to engage in a fight that would see the last major cavalry engagement in Western Europe. The battle soon erupted, and III Corps was shattered by incessant cavalry charges, losing over half its soldiers. The German Official History recorded 15,780 casualties and French casualties of 13,761 men.[68]

On 16 August, the French had a chance to sweep away the key Prussian defense, and to escape. Two Prussian corps had attacked the French advance guard, thinking that it was the rearguard of the retreat of the French Army of the Meuse. Despite this misjudgment the two Prussian corps held the entire French army for the whole day. Outnumbered 5 to 1, the extraordinary élan of the Prussians prevailed over gross indecision by the French. The French had lost the opportunity to win a decisive victory.[69]

Battle of Gravelotte

The Battle of Gravelotte, or Gravelotte–St. Privat (18 August), was the largest battle in the Franco-Prussian War. It was fought about 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Metz, where on the previous day, having intercepted the French army's retreat to the west at the Battle of Mars-La-Tour, the Prussians were now closing in to complete the destruction of the French forces. The combined German forces, under Field Marshal Count Helmuth von Moltke, were the Prussian First and Second Armies of the North German Confederation numbering about 210 infantry battalions, 133 cavalry squadrons, and 732 heavy cannons totaling 188,332 officers and men. The French Army of the Rhine, commanded by Marshal François-Achille Bazaine, numbering about 183 infantry battalions, 104 cavalry squadrons, backed by 520 heavy cannons, totaling 112,800 officers and men, dug in along high ground with their southern left flank at the town of Rozérieulles, and their northern right flank at St. Privat.

.jpg.webp)

On 18 August, the battle began when at 08:00 Moltke ordered the First and Second Armies to advance against the French positions. The French were dug in with trenches and rifle pits with their artillery and their mitrailleuses in concealed positions. Backed by artillery fire, Steinmetz's VII and VIII Corps launched attacks across the Mance ravine, all of which were defeated by French rifle and mitrailleuse firepower, forcing the two German corps' to withdraw to Rezonville. The Prussian 1st Guards Infantry Division assaulted French-held St. Privat and was pinned down by French fire from rifle pits and trenches. The Second Army under Prince Frederick Charles used its artillery to pulverize the French position at St. Privat. His XII Corps took the town of Roncourt and helped the Guard conquer St. Privat, while Eduard von Fransecky's II Corps advanced across the Mance ravine. The fighting died down at 22:00.

The next morning the French Army of the Rhine retreated to Metz where they were besieged and forced to surrender two months later. A grand total of 20,163 German troops were killed, wounded or missing in action during the August 18 battle. The French losses were 7,855 killed and wounded along with 4,420 prisoners of war (half of them were wounded) for a total of 12,275.

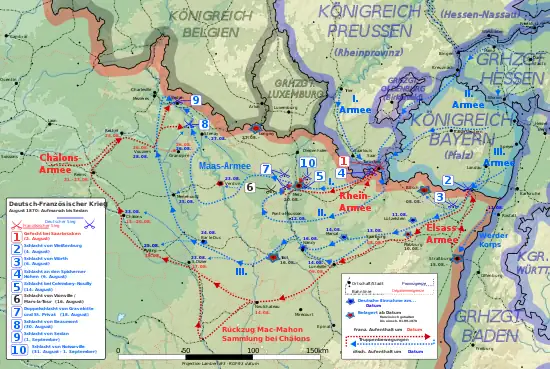

Siege of Metz

With the defeat of Marshal Bazaine's Army of the Rhine at Gravelotte, the French retired to Metz, where they were besieged by over 150,000 Prussian troops of the First and Second Armies. Further military operations on the part of the army under Bazaine's command have drawn numerous criticisms from historians against its commander. It is stated with malicious irony that his occupation at that time was writing orders on hygiene and discipline, as well as playing dominoes.[70] Bazaine's surprising inactivity was a great relief to Moltke, who now had time to improve his lines around Metz and intensify the hunt for MacMahon.[71]

At this time, Napoleon III and MacMahon formed the new French Army of Châlons to march on to Metz to rescue Bazaine. Napoleon III personally led the army with Marshal MacMahon in attendance. The Army of Châlons marched northeast towards the Belgian border to avoid the Prussians before striking south to link up with Bazaine. The Prussians took advantage of this maneuver to catch the French in a pincer grip. Moltke left the Prussian First and Second Armies besieging Metz, except three corps detached to form the Army of the Meuse under the Crown Prince of Saxony. With this army and the Prussian Third Army, Moltke marched northward and caught up with the French at Beaumont on 30 August. After a sharp fight in which they lost 5,000 men and 40 cannons, the French withdrew toward Sedan. Having reformed in the town, the Army of Châlons was immediately isolated by the converging Prussian armies. Napoleon III ordered the army to break out of the encirclement immediately. With MacMahon wounded on the previous day, General Auguste Ducrot took command of the French troops in the field.

Battle of Sedan

On 1 September 1870, the battle opened with the Army of Châlons, with 202 infantry battalions, 80 cavalry squadrons and 564 guns, attacking the surrounding Prussian Third and Meuse Armies totaling 222 infantry battalions, 186 cavalry squadrons and 774 guns. General De Wimpffen, the commander of the French V Corps in reserve, hoped to launch a combined infantry and cavalry attack against the Prussian XI Corps. But by 11:00, Prussian artillery took a toll on the French while more Prussian troops arrived on the battlefield. The struggle in the conditions of encirclement turned out to be absolutely impossible for the French — their front was shot through with artillery fire from three sides. The French cavalry, commanded by General Margueritte, launched three desperate attacks on the nearby village of Floing where the Prussian XI Corps was concentrated. Margueritte was mortally wounded leading the very first charge, dying 4 days later, and the two additional charges led to nothing but heavy losses. By the end of the day, with no hope of breaking out, Napoleon III called off the attacks. The French lost over 17,000 men, killed or wounded, with 21,000 captured. The Prussians reported their losses at 2,320 killed, 5,980 wounded and 700 captured or missing. By the next day, on 2 September, Napoleon III surrendered and was taken prisoner with 104,000 of his soldiers. It was an overwhelming victory for the Prussians, who had captured an entire French army and the leader of France. They subsequently paraded the defeated French army in view of the besieged army in Metz, which had an impact on the morale of the defenders. The defeat of the French at Sedan had decided the war in Prussia's favour. One French army was now immobilised and besieged in the city of Metz, and nothing was preventing a Prussian invasion.[72]

Surrender of Metz

Bazaine, a well-known Bonapartist, at this time allowed himself to be carried away by illusory plans for a political role in France. Unconventional military plans were put forth, by which the Germans would allow the army under Bazaine's command to withdraw from the fortress of Metz to retreat to the south of France, where it would remain until the German armies captured Paris, eliminated the political usurpers and made room for the legitimate imperial authorities with the support of Bazaine's army.[73] Even ignoring moral issues and potential public outcry, this plan seems completely unrealistic. Bismarck and Moltke answered Bazaine's offer of "cooperation" against the "republican menace" with an indifferent shrug.[74] The German press, undoubtedly at the instigation of Bismarck, widely covered this topic, and reported the details of Bazaine's negotiations. The French press could only remain completely silent on this issue. With whom Bazaine negotiated still raises questions among historians. "For a decade, the French were considered him (M. Edmond Regnier) a sinister figure, almost certainly an agent of Bismarck. They would have been more justified in thinking him a buffoon".[75] Undoubtedly, the politically motivated actions of Commander Bazaine led to the passivity of the encircled army at Metz and contributed to the defeat of not only this army, but the country as a whole. Bazaine's army surrendered on 26 October. 173,000 people surrendered, with the Prussians capturing the huge amount of military equipment located in Metz. After the war, Marshal Bazaine was convicted by a French military court.

War of the Government of National Defence

Government of National Defence

When news of Napoleon III's surrender at Sedan arrived in Paris, the Second Empire was overthrown by a popular uprising. On 4 September, Jules Favre, Léon Gambetta, and General Louis-Jules Trochu proclaimed a Provisional Government called the Government of National Defence and a Third Republic.[76] After the German victory at Sedan, most of the French standing army was either besieged in Metz or prisoner of the Germans, who hoped for an armistice and an end to the war. Bismarck wanted an early peace but had difficulty in finding a legitimate French authority to negotiate with. The Emperor was a captive and the Empress in exile, but there had been no abdication de jure and the army was still bound by an oath of allegiance to the defunct imperial regime; on the other hand, the Government of National Defence had no electoral mandate.[77]

Prussia's intention was to weaken the political position of France abroad. The defensive position of the new French authorities, who offered Germany an honorable peace and reimbursement of the costs of the war, was presented by Prussia as aggressive; they rejected the conditions put forward and demanded the annexation of the French provinces of Alsace and part of Lorraine. Bismarck was dangling the emperor over the republic's head, calling Napoleon III "the legitimate ruler of France" and dismissing Gambetta's new republic as no more than "un coup de parti" – "a partisan coup".[72] This policy was to some extent successful; the European press discussed the legitimacy of the French authorities, and Prussia's aggressive position was to some extent understood. Only the United States and Spain recognized the Government of National Defence immediately after the announcement; other countries refused to do this for some time.[78] The question of legitimacy is rather strange for France after the coup d'état of 1851.

The Germans expected to negotiate an end to the war, but while the republican government was amenable to war reparations or ceding colonial territories in Africa or South East Asia, it would go no further. On behalf of the Government of National Defense, Favre declared on 6 September that France would not "yield an inch of its territory nor a stone of its fortresses".[79] The republic then renewed the declaration of war, called for recruits in all parts of the country, and pledged to drive the German troops out of France by a guerre à outrance (overwhelming attack).[80] The Germans continued the war, yet could not pin down any proper military opposition in their vicinity. As the bulk of the remaining French armies was digging in near Paris, the German leaders decided to put pressure upon the enemy by attacking there. By 15 September, German troops had reached the outskirts and Moltke issued the orders to surround the city. On 19 September, the Germans surrounded it and erected a blockade, as already established at Metz, completing the encirclement on 20 September. Bismarck met Favre on 18 September at the Château de Ferrières and demanded a frontier immune to a French war of revenge, which included Strasbourg, Alsace, and most of the Moselle department in Lorraine, of which Metz was the capital. In return for an armistice for the French to elect a National Assembly, Bismarck demanded the surrender of Strasbourg and the fortress city of Toul. To allow supplies into Paris, one of the perimeter forts had to be handed over. Favre was unaware that Bismarck's real aim in making such extortionate demands was to establish a durable peace on Germany's new western frontier, preferably by a peace with a friendly government, on terms acceptable to French public opinion. An impregnable military frontier was an inferior alternative to him, favoured only by the militant nationalists on the German side.[81]

When the war had begun, European public opinion heavily favoured the Germans; many Italians attempted to sign up as volunteers at the Prussian embassy in Florence and a Prussian diplomat visited Giuseppe Garibaldi in Caprera. Bismarck's demand that France surrender sovereignty over Alsace caused a dramatic shift in that sentiment in Italy, which was best exemplified by the reaction of Garibaldi soon after the revolution in Paris, who told the Movimento of Genoa on 7 September 1870 that "Yesterday I said to you: war to the death to Bonaparte. Today I say to you: rescue the French Republic by every means."[82] Garibaldi went to France and assumed command of the Army of the Vosges, with which he operated around Dijon till the end of the war.

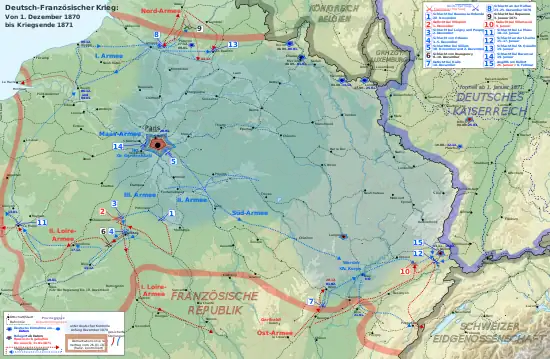

The energetic actions of a part of the government (Delegation) in Tours under Gambetta's leadership led to significant success in the formation of a new army. 11 new corps were formed, Nos. XVI–XXVI. "3 of these corps were ready only by the end of January, when a truce was already concluded, but 8 corps took a hot part in the battles. In less than 4 months, with persistent battles at the front, a new mass army was created. The average success of the formation was equal to 6 thousand infantrymen and 2 batteries per day. This success was achieved despite the fact that the military industry and warehouses were concentrated mainly in Paris and everything in the province had to be improvised anew — chiefs, weapons, camps, uniforms, ammunition, equipment, baggage. Many branches of the military industry were re-established in the province. Freedom of communication with foreign markets brought significant benefits: it was possible to make large purchases on foreign markets-mainly English, Belgian and American markets, the artillery created by Gambetta in 4 months — 238 batteries — was one and a half times larger than the artillery of imperial France and technically stood higher.[83]

While the Germans had a 2:1 numerical advantage before Napoleon III's surrender, this French recruitment gave them a 2:1 or 3:1 advantage. The French more than tripled their forces during the war, but the Germans did not increase theirs as much; the number of 888,000 mobilized by the North German Union in August increased by only 2% after 3½ months, and by the end of the war, six months later, only by 15%, which did not even balance the losses incurred. Prussia was completely unaware of the feverish activity of permanent mobilization. This disparity in forces created a crisis for the Germans at the front in November 1870,[84] which only the release of the large forces besieging the fortress of Metz allowed them to overcome.

Siege of Paris

Prussian forces commenced the siege of Paris on 19 September 1870. Faced with the blockade, the new French government called for the establishment of several large armies in the French provinces. These new bodies of troops were to march towards Paris and attack the Germans there from various directions at the same time. Armed French civilians were to create a guerilla force—the so-called Francs-tireurs—for the purpose of attacking German supply lines.

Bismarck was an active supporter of the bombardment of the city. He sought to end the war as soon as possible, very much fearing a change in the international situation unfavorable to Prussia, as he himself called it "the intervention of neutrals".[85] Therefore, Bismarck constantly and actively insisted on the early start of the bombardment, despite all the objections of the military command. Von Blumenthal, who commanded the siege, was opposed to the bombardment on moral grounds. In this he was backed by other senior military figures such as the Crown Prince and Moltke. Nevertheless, in January, the Germans fired some 12,000 shells (300–400 daily) into the city.[86]

The siege of the city caused great hardships for the population, especially for the poor from cold and hunger.

Loire campaign

Dispatched from Paris as the republican government emissary, Léon Gambetta flew over the German lines in a balloon inflated with coal gas from the city's gasworks and organized the recruitment of the Armée de la Loire. Rumors about an alleged German "extermination" plan infuriated the French and strengthened their support of the new regime. Within a few weeks, five new armies totalling more than 500,000 troops were recruited.[87]

The Germans dispatched some of their troops to the French provinces to detect, attack and disperse the new French armies before they could become a menace. The Germans were not prepared for an occupation of the whole of France.

On 10 October, hostilities began between German and French republican forces near Orléans. At first, the Germans were victorious but the French drew reinforcements and defeated a Bavarian force at the Battle of Coulmiers on 9 November. After the surrender of Metz, more than 100,000 well-trained and experienced German troops joined the German 'Southern Army'. The French were forced to abandon Orléans on 4 December, and were finally defeated at the Battle of Le Mans (10–12 January). A second French army which operated north of Paris was turned back at the Battle of Amiens (27 November), the Battle of Bapaume (3 January 1871) and the Battle of St. Quentin (13 January).[88]

Northern campaign

Following the Army of the Loire's defeats, Gambetta turned to General Faidherbe's Army of the North.[89] The army had achieved several small victories at towns such as Ham, La Hallue, and Amiens and was protected by the belt of fortresses in northern France, allowing Faidherbe's men to launch quick attacks against isolated Prussian units, then retreat behind the fortresses. Despite access to the armaments factories of Lille, the Army of the North suffered from severe supply difficulties, which depressed morale. In January 1871, Gambetta forced Faidherbe to march his army beyond the fortresses and engage the Prussians in open battle. The army was severely weakened by low morale, supply problems, the terrible winter weather and low troop quality, whilst general Faidherbe was unable to command due to his poor health, the result of decades of campaigning in West Africa. At the Battle of St. Quentin, the Army of the North suffered a crushing defeat and was scattered, releasing thousands of Prussian soldiers to be relocated to the East.[90]

Eastern campaign

Following the destruction of the French Army of the Loire, remnants of the Loire army gathered in eastern France to form the Army of the East, commanded by general Charles-Denis Bourbaki. In a final attempt to cut the German supply lines in northeast France, Bourbaki's army marched north to attack the Prussian siege of Belfort and relieve the defenders.

The French troops had a significant advantage (110 thousand soldiers against 40 thousand). The French offensive was unexpected for the Germans and began quite successfully. By mid-January 1871, the French had reached the Lisaine River, just a few kilometers from the besieged fortress of Belfort.

In the battle of the Lisaine, Bourbaki's men failed to break through German lines commanded by General August von Werder. Bringing in the German 'Southern Army', General von Manteuffel then drove Bourbaki's army into the mountains near the Swiss border. Bourbaki attempted to commit suicide, but failed to inflict a fatal wound.[91] Facing annihilation, the last intact French army of 87,000 men (now commanded by General Justin Clinchant)[92] crossed the border and was disarmed and interned by the neutral Swiss near Pontarlier (1 February).

The besieged fortress of Belfort continued to resist until the signing of the armistice, repelling a German attempt to capture the fortress on 27 January, which was some consolation for the French in this stubborn and unhappy campaign.

Armistice

On 26 January 1871, the Government of National Defence based in Paris negotiated an armistice with the Prussians. With Paris starving, and Gambetta's provincial armies reeling from one disaster after another, French foreign minister Favre went to Versailles on 24 January to discuss peace terms with Bismarck. Bismarck agreed to end the siege and allow food convoys to immediately enter Paris (including trains carrying millions of German army rations), on condition that the Government of National Defence surrender several key fortresses outside Paris to the Prussians. Without the forts, the French Army would no longer be able to defend Paris.

Although public opinion in Paris was strongly against any form of surrender or concession to the Prussians, the Government realised that it could not hold the city for much longer, and that Gambetta's provincial armies would probably never break through to relieve Paris. President Trochu resigned on 25 January and was replaced by Favre, who signed the surrender two days later at Versailles, with the armistice coming into effect at midnight.

On 28 January, a truce was concluded for 21 days, after the exhaustion of food and fuel supplies, the Paris garrison capitulated, the National Guard retained its weapons, while German troops occupied part of the forts of Paris to prevent the possibility of resuming hostilities. But military operations continued in the eastern part of the country, in the area of operation of the Bourbaki army. The French side, having no reliable information about the outcome of the struggle, insisted on excluding this area from the truce in the hope of a successful outcome of the struggle.[94] The Germans did not dissuade the French.

Several sources claim that in his carriage on the way back to Paris, Favre broke into tears, and collapsed into his daughter's arms as the guns around Paris fell silent at midnight. At Bordeaux, Gambetta received word from Paris on 29 January that the Government had surrendered. Furious, he refused to surrender. Jules Simon, a member of the Government arrived from Paris by train on 1 February to negotiate with Gambetta. Another group of three ministers arrived in Bordeaux on 5 February and the following day Gambetta stepped down and surrendered control of the provincial armies to the Government of National Defence, which promptly ordered a cease-fire across France.

War at sea

Blockade

When the war began, the French government ordered a blockade of the North German coasts, which the small North German Federal Navy with only five ironclads and various minor vessels could do little to oppose. For most of the war, the three largest German ironclads were out of service with engine troubles; only the turret ship SMS Arminius was available to conduct operations. By the time engine repairs had been completed, the French fleet had already departed.[95] The blockade proved only partially successful due to crucial oversights by the planners in Paris. Reservists that were supposed to be at the ready in case of war, were working in the Newfoundland fisheries or in Scotland. Only part of the 470-ship French Navy put to sea on 24 July. Before long, the French navy ran short of coal, needing 200 short tons (180 t) per day and having a bunker capacity in the fleet of only 250 short tons (230 t). A blockade of Wilhelmshaven failed, and conflicting orders about operations in the Baltic Sea or a return to France made the French naval efforts futile. Spotting a blockade-runner became unwelcome because of the question du charbon; pursuit of Prussian ships quickly depleted the coal reserves of the French ships.[96][97] But the main reason for the only partial success of the naval operation was the fear of the French command to risk political complications with Great Britain. This deterred the French command from trying to interrupt German trade under the British flag.[98] Despite the limited measures of the blockade, it still created noticeable difficulties for German trade. "The actual captures of German ships were eighty in number".[99]

To relieve pressure from the expected German attack into Alsace-Lorraine, Napoleon III and the French high command planned a seaborne invasion of northern Germany as soon as war began. The French expected the invasion to divert German troops and to encourage Denmark to join in the war, with its 50,000-strong army and the Royal Danish Navy. They discovered that Prussia had recently built defences around the big North German ports, including coastal artillery batteries with Krupp heavy artillery, which with a range of 4,000 yards (3,700 m), had double the range of French naval guns. The French Navy lacked the heavy guns to engage the coastal defences and the topography of the Prussian coast made a seaborne invasion of northern Germany impossible.[100]

The French Marines intended for the invasion of northern Germany were dispatched to reinforce the French Army of Châlons and fell into captivity at Sedan along with Napoleon III. A shortage of officers, following the capture of most of the professional French army at the siege of Metz and at the Battle of Sedan, led to naval officers being sent from their ships to command hastily assembled reservists of the Garde Mobile.[101] As the autumn storms of the North Sea forced the return of more of the French ships, the blockade of the north German ports diminished and in September 1870 the French navy abandoned the blockade for the winter. The rest of the navy retired to ports along the English Channel and remained in port for the rest of the war.[101]

War crimes

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 resulted in numerous war crimes committed by the Prussian army. One notable war crime committed during the conflict was the execution of prisoners of war. Reports indicate that several hundred French prisoners were summarily executed by Prussian soldiers. This included the execution of a group of over 200 French soldiers at the village of Dornach, which was subsequently referred to as the "Dornach atrocities".[104]

Prussian soldiers were also accused of committing acts of violence against civilians, including murder, rape, and the destruction of property.[105]

Aftermath

Analysis

The quick German victory over the French stunned neutral observers, many of whom had expected a French victory and most of whom had expected a long war. The strategic advantages which the Germans had were not appreciated outside Germany until after hostilities had ceased. Other countries quickly discerned the advantages given to the Germans by their military system, and adopted many of their innovations, particularly the general staff, universal conscription, and highly detailed mobilization systems.[106]

The Prussian General Staff developed by Moltke proved to be extremely effective, in contrast to the traditional French school. This was in large part because the Prussian General Staff was created to study previous Prussian operations and learn to avoid mistakes. The structure also greatly strengthened Moltke's ability to control large formations spread out over significant distances.[107] The Chief of the General Staff, effectively the commander in chief of the Prussian army, was independent of the minister of war and answered only to the monarch.[108] The French General Staff—along with those of every other European military—was little better than a collection of assistants for the line commanders. This disorganization hampered the French commanders' ability to exercise control of their forces.[109]

In addition, the Prussian military education system was superior to the French model; Prussian staff officers were trained to exhibit initiative and independent thinking. Indeed, this was Moltke's expectation.[110] The French, meanwhile, suffered from an education and promotion system that stifled intellectual development. According to the military historian Dallas Irvine, the system:

was almost completely effective in excluding the army's brain power from the staff and high command. To the resulting lack of intelligence at the top can be ascribed all the inexcusable defects of French military policy.[108]

Albrecht von Roon, the Prussian Minister of War from 1859 to 1873, put into effect a series of reforms of the Prussian military system in the 1860s. Among these were two major reforms that substantially increased the military power of Germany. The first was a reorganization of the army that integrated the regular army and the Landwehr reserves.[111] The second was the provision for the conscription of every male Prussian of military age in the event of mobilization.[112] Thus, although the population of France was greater than the population of all of the Northern German states that participated in the war, the Germans mobilized more soldiers for battle.

| Population in 1870 | Mobilized | |

|---|---|---|

| 38,000,000 | 500,000 | |

| 32,000,000 | 550,000 |

At the start of the Franco-Prussian War, 462,000 German soldiers concentrated on the French frontier while only 270,000 French soldiers could be moved to face them, the French army having lost 100,000 stragglers before a shot was fired, through poor planning and administration.[32] This was partly due to the peacetime organisations of the armies. Each Prussian Corps was based within a Kreis (literally "circle") around the chief city in an area. Reservists rarely lived more than a day's travel from their regiment's depot. By contrast, French regiments generally served far from their depots, which in turn were not in the areas of France from which their soldiers were drawn. Reservists often faced several days' journey to report to their depots, and then another long journey to join their regiments. Large numbers of reservists choked railway stations, vainly seeking rations and orders.[113]

The effect of these differences was accentuated by the peacetime preparations. The Prussian General Staff had drawn up minutely detailed mobilization plans using the railway system, which in turn had been partly laid out in response to recommendations of a Railway Section within the General Staff. The French railway system, with competing companies, had developed purely from commercial pressures and many journeys to the front in Alsace and Lorraine involved long diversions and frequent changes between trains. There was no system of military control of the railways and officers simply commandeered trains as they saw fit. Rail sidings and marshalling yards became choked with loaded wagons, with nobody responsible for unloading them or directing them to the destination.[114]

France also suffered from an outdated tactical system. Although referred to as "Napoleonic tactics", this system was developed by Antoine-Henri Jomini during his time in Russia. Surrounded by a rigid aristocracy with a "Sacred Social Order" mentality, Jomini's system was equally rigid and inflexible. His system simplified several formations that were meant for an entire army, using battalions as the building blocks. His system was simple, but only strong enough to attack in one direction. The system was adopted by the Bourbons to prevent a repeat of when Napoleon I had returned to France, and Napoleon III retained the system upon his ascension to power (hence why they became associated with his family name). The Prussians in contrast did not use battalions as their basic tactical unit, and their system was much more flexible. Companies were formed into columns and attacked in parallel, rather than as a homogeneous battalion-sized block. Attacking in parallel allowed each company to choose its own axis of advance and make the most of local cover. It also permitted the Prussians to fire at oblique angles, raking the French lines with rifle fire. Thus, even though the Prussians had inferior rifles, they still inflicted more casualties with rifle fire than the French, with 53,900 French killed by the Dreyse (70% of their war casualties) versus 25,475 Germans killed by the Chassepot (96% of their war casualties).

Although Austria-Hungary and Denmark had both wished to avenge their recent military defeats against Prussia, they chose not to intervene in the war due to a lack of confidence in the French. These countries did not have a documented alliance with France, and they were too late to start a war. After the rapid and stunning victories of Prussia, they preferred to abandon any plans to intervene in the war altogether. Napoleon III also failed to cultivate alliances with the Russian Empire and the United Kingdom, partially due to the diplomatic efforts of the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck had bought Tsar Alexander II's complicity by promising to help restore his naval access to the Black Sea and Mediterranean (cut off by the treaties ending the Crimean War), other powers were less biddable.[115] "Seizing upon the distraction of the Franco-Prussian War, Russia in November 1870 had begun rebuilding its naval bases in the Black Sea, a clear violation of the treaty that had ended the Crimean War fourteen years earlier".[116] After the peace of Frankfurt in 1871, a rapprochement between France and Russia was born. "Instead of forging ties with Russia in the east and further crippling France in the west, Bismarck's miscalculation had opened the door to future relations between Paris and St. Petersburg. The culmination of this new relationship will finally be the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894; an alliance that explicitly refers to the perceived threat of Germany and its military response".[117]

Great Britain saw nothing wrong with the strengthening of Prussia on the European continent, viewing France as its traditional rival in international affairs. Lord Palmerston, the head of the British cabinet in 1865, wrote: "The current Prussia is too weak to be honest and independent in its actions. And, taking into account the interests of the future, it is highly desirable for Germany as a whole became strong, so she was able to keep the ambitious and warlike nation, France, and Russia, which compress it from the West and the East".[118] English historians criticize the then British policy, pointing out that Palmerston misunderstood Bismarck's policy due to his adherence to outdated ideas.[119] Over time, Britain began to understand that the military defeat of France meant a radical change in the European balance of power. In the future, the development of historical events is characterized by a gradual increase in Anglo-German contradictions. "The colonial quarrels, naval rivalry and disagreement over the European balance of power which drove Britain and Germany apart, were in effect the strategical and geopolitical manifestations of the relative shift in the economic power of these two countries between 1860 and 1914".[120]

After the Peace of Prague in 1866, the nominally independent German states of Saxony, Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and Hesse-Darmstadt (the southern part that was not included in the North German Union) remained. Despite the fact that there was a strong opposition to Prussia in the ruling circles and in the war of 1866 they participated on the side of Austria against Prussia, they were forced to reckon with a broad popular movement in favor of German unity and were also afraid of angering their strong neighbor in the form of Prussia. After the diplomatic provocation in Bad Ems, these states had no room for maneuver, the war was presented by Bismarck as a war for national independence against an external enemy. All these states joined the Prussian war from the very beginning of hostilities. In January 1871, these states became part of the German Empire.

The French breech-loading rifle, the Chassepot, had a longer range than the German needle gun; 1,400 metres (1,500 yd) compared to 550 m (600 yd). The French also had an early machine-gun type weapon, the mitrailleuse, which could fire its thirty-seven barrels at a range of around 1,100 m (1,200 yd).[121] It was developed in such secrecy that little training with the weapon had occurred, leaving French gunners with little experience; the gun was treated like artillery and in this role it was ineffective. Worse still, once the small number of soldiers who had been trained how to use the new weapon became casualties, there were no replacements who knew how to operate the mitrailleuse.[122]

The French were equipped with bronze, rifled muzzle-loading artillery, while the Prussians used new steel breech-loading guns, which had a far longer range and a faster rate of fire.[123] Prussian gunners strove for a high rate of fire, which was discouraged in the French army in the belief that it wasted ammunition. In addition, the Prussian artillery batteries had 30% more guns than their French counterparts. The Prussian guns typically opened fire at a range of 2–3 kilometres (1.2–1.9 mi), beyond the range of French artillery or the Chassepot rifle. The Prussian batteries could thus destroy French artillery with impunity, before being moved forward to directly support infantry attacks.[124] The Germans fired 30,000,000 rounds of small arms ammunition and 362,662 field artillery rounds.[125]

Effects on military thought

The events of the Franco-Prussian War had great influence on military thinking over the next forty years. Lessons drawn from the war included the need for a general staff system, the scale and duration of future wars and the tactical use of artillery and cavalry. The bold use of artillery by the Prussians, to silence French guns at long range and then to directly support infantry attacks at close range, proved to be superior to the defensive doctrine employed by French gunners. Likewise, the war showed that breech-loading cannons were superior to muzzle-loaded cannons, just as the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 had demonstrated for rifles. The Prussian tactics and designs were adopted by European armies by 1914, exemplified in the French 75, an artillery piece optimised to provide direct fire support to advancing infantry. Most European armies ignored the evidence of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 which suggested that infantry armed with new smokeless-powder rifles could engage gun crews effectively in the open. This forced gunners to fire at longer range using indirect fire, usually from a position of cover.[126] The heavy use of fortifications and dugouts in the Russo-Japanese war also greatly undermined the usefulness of field artillery which was not designed for indirect fire.

At the Battle of Mars-La-Tour, the Prussian 12th Cavalry Brigade, commanded by General Adalbert von Bredow, conducted a charge against a French artillery battery. The attack was a costly success and came to be known as "von Bredow's Death Ride", but which nevertheless was held to prove that cavalry charges could still prevail on the battlefield. Use of traditional cavalry on the battlefields of 1914 proved to be disastrous, due to accurate, long-range rifle fire, machine-guns and artillery.[127] Bredow's attack had succeeded only because of an unusually effective artillery bombardment just before the charge, along with favorable terrain that masked his approach.[128][127]

A third influence was the effect on notions of entrenchment and its limitations. While the American Civil War had famously involved entrenchment in the final years of the war, the Prussian system had overwhelmed French attempts to use similar tactics. With Prussian tactics seeming to make entrenchment and prolonged offensive campaigns ineffective, the experience of the American Civil War was seen as that of a musket war, not a rifle war. Many European armies were convinced of the viability of the "cult of the offensive" because of this, and focused their attention on aggressive bayonet charges over infantry fire. These would needlessly expose men to artillery fire in 1914, and entrenchment would return with a vengeance.

Casualties

The Germans deployed a total of 33,101 officers and 1,113,254 men into France, of whom they lost 1,046 officers and 16,539 enlisted men killed in action. Another 671 officers and 10,050 men died of their wounds, for total battle deaths of 28,306. Disease killed 207 officers and 11,940 men, with typhoid accounting for 6,965. 4,009 were missing and presumed dead; 290 died in accidents and 29 committed suicide. Among the missing and captured were 103 officers and 10,026 men. The wounded amounted to 3,725 officers and 86,007 men.[4]

French battle deaths were 77,000, of which 41,000 were killed in action and 36,000 died of wounds. More than 45,000 died of sickness. Total deaths were 138,871, with 136,540 being suffered by the army and 2,331 by the navy. The wounded totaled 137,626; 131,000 for the army and 6,526 for the navy. French prisoners of war numbered 383,860. In addition, 90,192 French soldiers were interned in Switzerland and 6,300 in Belgium.[4]

During the war the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) established an international tracing agency in Basel for prisoners of that war. The holdings of the "Basel Agency" were later transferred to the ICRC headquarters in Geneva and integrated into the ICRC archives, where they are accessible today.[129]

Subsequent events

Prussian reaction and withdrawal

The Prussian Army, under the terms of the armistice, held a brief victory parade in Paris on 1 March; the city was silent and draped with black and the Germans quickly withdrew. Bismarck honoured the armistice, by allowing train loads of food into Paris and withdrawing Prussian forces to the east of the city, prior to a full withdrawal once France agreed to pay a five billion franc war indemnity.[130] The indemnity was proportioned, according to population, to be the exact equivalent to the indemnity imposed by Napoleon on Prussia in 1807.[130] At the same time, Prussian forces were concentrated in the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. An exodus occurred from Paris as some 200,000 people, predominantly middle-class, went to the countryside.

Paris Commune

During the war, the Paris National Guard, particularly in the working-class neighbourhoods of Paris, had become highly politicised and units elected officers; many refused to wear uniforms or obey commands from the national government. National guard units tried to seize power in Paris on 31 October 1870 and 22 January 1871. On 18 March 1871, when the regular army tried to remove cannons from an artillery park on Montmartre, National Guard units resisted and killed two army generals. The national government and regular army forces retreated to Versailles and a revolutionary government was proclaimed in Paris. A commune was elected, which was dominated by socialists, anarchists and revolutionaries. The red flag replaced the French tricolour and a civil war began between the Commune and the regular army, which attacked and recaptured Paris from 21–28 May in the Semaine Sanglante ("bloody week").[131][132][133]

During the fighting, the Communards killed around 500 people, including Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris, and burned down many government buildings, including the Tuileries Palace and the Hotel de Ville.[134] Communards captured with weapons were routinely shot by the army and Government troops killed between 7,000 and 30,000 Communards, both during the fighting and in massacres of men, women, and children during and after the Commune.[135][132][136][137] More recent histories, based on studies of the number buried in Paris cemeteries and in mass graves after the fall of the Commune, put the number killed at between 6,000 and 10,000.[138] Twenty-six courts were established to try more than 40,000 people who had been arrested, which took until 1875 and imposed 95 death sentences, of which 23 were inflicted. Forced labour for life was imposed on 251 people, 1,160 people were transported to "a fortified place" and 3,417 people were transported. About 20,000 Communards were held in prison hulks until released in 1872 and a great many Communards fled abroad to Britain, Switzerland, Belgium or the United States. The survivors were amnestied by a bill introduced by Gambetta in 1880 and allowed to return.[139]

1871 Kabyle revolt

In 1830, the French army invaded and conquered the Beylik of Algiers. Afterwards, France colonized the country, setting up its own administration over Algeria. The withdrawal of a large proportion of the army stationed in French Algeria to serve in the Franco-Prussian War had weakened France's control of the territory, while reports of defeats undermined French prestige amongst the indigenous population. The most serious native insurrection since the time of Emir Abdelkader was the 1871 Mokrani Revolt in the Kabylia, which spread through much of Algeria. By April 1871, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population.[140]

German unification and power

.jpg.webp)

The creation of a unified German Empire (which excluded Austria) greatly disturbed the balance of power that had been created with the Congress of Vienna after the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Germany had established itself as a major power in continental Europe, boasting one of the most powerful and professional armies in the world.[141] Although Britain remained the dominant world power overall, British involvement in European affairs during the late 19th century was limited, owing to its focus on colonial empire-building, allowing Germany to exercise great influence over the European mainland.[142] Anglo-German straining of tensions was somewhat mitigated by several prominent relationships between the two powers, such as the Crown Prince's marriage with the daughter of Queen Victoria.

Einheit—unity—was achieved at the expense of Freiheit—freedom. According to Karl Marx, the German Empire became "a military despotism cloaked in parliamentary forms with a feudal ingredient, influenced by the bourgeoisie, festooned with bureaucrats and guarded by police." Likewise, many historians would see Germany's "escape into war" in 1914 as a flight from all of the internal-political contradictions forged by Bismarck at Versailles in the fall of 1870.[143]

French reaction and Revanchism

The defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the birth of Revanchism (literally, "revenge-ism") in France, characterised by a deep sense of bitterness, hatred and demand for revenge against Germany. This was particularly manifested in loose talk of another war with Germany in order to reclaim Alsace and Lorraine.[144][145] It also led to the development of nationalist ideologies emphasising "the ideal of the guarded, self-referential nation schooled in the imperative of war", an ideology epitomised by figures such as General Georges Ernest Boulanger in the 1880s.[146] Paintings that emphasized the humiliation of the defeat became in high demand, such as those by Alphonse de Neuville.[147] Revanchism was not a major cause of war in 1914 because it faded after 1880. J.F.V. Keiger says, "By the 1880s Franco-German relations were relatively good."[148] The French public had very little interest in foreign affairs and elite French opinion was strongly opposed to war with its more powerful neighbor.[149] The elites were now calm and considered it a minor issue.[150] The Alsace-Lorraine issue remained a minor theme after 1880, and Republicans and Socialists systematically downplayed the issue. Return did not become a French war aim until after World War I began.[151][152]

See also

Notes

- Under the Government of National Defense.

- French: Guerre franco-allemande de 1870, German: Deutsch-Französischer Krieg, pronounced [dɔʏtʃ fʁanˌtsøːzɪʃɐ ˈkʁiːk] ⓘ

References

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 184, 33,101 officers and 1,113,254 men were deployed into France. A further 348,057 officers and men were mobilized and stayed in Germany..

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 184.

- Howard 1991, p. 39.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 187.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 187, of which 17,585 killed in action, 10,721 died of wounds, 12,147 died from disease, 290 died in accidents, 29 committed suicide and 4,009 were missing and presumed dead.

- Nolte 1884, pp. 526–527.

- Heath & Cocolin 2020, pp. 8.

- Nolte 1884, p. 527.

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 187, of which 41,000 killed in action, 36,000 died of wounds and 45,000 died from disease.

- German General Staff 1884, p. 247.

- Bodart 1916, p. 148, At least 370,000 captured.

- Éric Anceau, "Aux origines de la Guerre de 1870", in France-Allemagne(s) 1870–1871. La guerre, la Commune, les mémoires, (under the direction of Mathilde Benoistel, Sylvie Le Ray-Burimi, Christophe Pommier) Gallimard-Musée de l'Armée, 2017, p. 49–50.

- Ramm 1967, pp. 308–313, highlights three difficulties with the argument that Bismarck planned or provoked a French attack..

- Milza 2009, p. 39.

- Milza 2009, pp. 40–41.

- Howard 1991, p. 40.

- Milza 2009, p. 41.

- Howard 1991, p. 45.

- Wawro 2003, p. 18.

- von Bismarck 1899, p. 58.

- Britannica: Franco-German War.

- von Bismarck & von Poschinger 1900, p. 87.

- Howard 1991, p. 41.

- Wawro 2002, p. 101.

- Milza 2009, p. 49.

- German General Staff 1881, p. 8.

- German General Staff 1881, pp. 34–35.

- Milza 2009, pp. 57–59.

- Wawro 2003, p. 85.

- Vinogradov, V. N. (2005). "Was there a connection between the triumph of France in the Crimean War and its defeat at Sedan?". New and Recent History (in Russian) (5).

- McElwee 1974, p. 43.

- McElwee 1974, p. 46.

- Wawro 2002, p. 102.

- Wawro 2002, p. 103.

- Howard 1991, p. 4.

- Palmer 2010, p. 20.

- Ascoli 2001, p. 9.

- Elliot-Wright & Shann 1993, p. 29.

- Barry 2009a, p. 43.

- Wawro 2002, p. 89.

- Wawro 2002, p. 110.

- Palmer 2010, p. 30.

- Wawro 2002, p. 113.

- Wawro 2003, p. 58.

- Zabecki 2008, pp. 5–7.

- Wawro 2003, p. 47.

- Howard 1991, p. 78.

- Howard 1991, pp. 69, 78–79.

- Wawro 2003, pp. 66–67.

- Howard 1991, pp. 47, 48, 60.

- Wawro 2003, pp. 85, 86, 90.

- Wawro 2003, pp. 87, 90.

- Wawro 2003, p. 94.

- Howard 1991, p. 82.

- Wawro 2003, p. 95.

- Howard 1991, pp. 100–101.

- Howard 1991, p. 101.

- Wawro 2003, pp. 97, 98, 101.

- Wawro 2003, pp. 101–103.

- Howard 1991, pp. 101–103.

- Wawro 2003, p. 108.

- Howard 1991, pp. 87–88.

- Howard 1991, pp. 89–90.

- Howard 1991, pp. 92–93.

- Howard 1991, pp. 98–99.

- Howard 1979, pp. 108–117.

- Howard 1979, p. 145.

- Howard 1979, pp. 152–161.

- Howard 1979, pp. 160–163.

- Wawro 2003, p. 196.

- Wawro 2003, p. 201.

- Wawro 2003, p. 240.

- Wawro 2003, p. 244.

- Wawro 2003, p. 247.

- Howard, Michael (2001) [1961]. The Franco-Prussian War: The German Invasion of France 1870–1871. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26671-8

- Baldick 1974, pp. 20–21.

- Howard 1979, pp. 228–231.

- Wawro 2003, p. 239.

- Craig 1980, p. 31.

- Howard 1979, p. 234.

- Howard 1991, pp. 230–233.

- Ridley 1976, p. 602.

- Свечин (Svechin) 1928, p. 327.