Arthur Szyk

Arthur Szyk (Polish: Artur Szyk [ˈar.tur ʂɨk]; see Polish phonology); June 3, 1894 – September 13, 1951[1]) was a Polish-born Jewish artist who worked primarily as a book illustrator and political artist throughout his career. Arthur Szyk was born into a prosperous middle-class Jewish family in Łódź,[2][3] in the part of Poland which was under Russian rule in the 19th century. An acculturated Polish Jew, Szyk always proudly regarded himself both as a Pole and a Jew.[4] From 1921, he lived and created his works mainly in France and Poland, and in 1937 he moved to the United Kingdom. In 1940, he settled permanently in the United States, where he was granted American citizenship in 1948.

Arthur Szyk | |

|---|---|

%252C_Portrait_with_pipe_(c._1946)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) Szyk, circa 1945 | |

| Born | Artur Szyk 3 June 1894 |

| Died | 13 September 1951 (aged 57) |

| Resting place | New Montefiore Cemetery, Farmingdale, New York |

| Nationality | Polish American |

| Education | Académie Julian, Paris Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts, Kraków |

| Known for | Drawing, caricature, book illustration, illuminated manuscript, watercolor painting |

| Notable work | Statute of Kalisz (1932); Washington and his Times (1932); Twenty Pictures from the Glorious Days of the Polish-American Fraternity (1939); The Haggadah (1940); The New Order (1941); Andersen's Fairy Tales (1945); Ink & Blood: A Book of Drawings (1946); Pathways Through the Bible (1946); Visual History of Nations (1945–1949) |

| Awards | Ordre des Palmes Académiques (France), 1923; Gold Cross of Merit (Poland), 1931; George Washington Bicentennial Medal (United States), 1932 |

Arthur Szyk became a renowned artist and book illustrator as early as the interwar period. His works were exhibited and published not only in Poland but also in France, the United Kingdom, Israel and the United States. However, he gained broad popularity in the United States primarily through his political caricatures, in which, after the outbreak of World War II, he savaged the policies and personalities of the leaders of the Axis powers. After the war, he also devoted himself to Zionist political issues, especially the support of the creation of the state of Israel.

Szyk's work is characterized in its material content by social and political commitment, and in its formal aspect by its rejection of modernism and embrace of the traditions of medieval and renaissance painting, especially illuminated manuscripts from those periods.

Today, Szyk is known and exhibited only in his last country of residence, the United States.

Background and youth

Arthur Szyk,[5] the son of Solomon Szyk and his wife Eugenia, was born in Łódź, in Russian partition of Poland, on June 3, 1894. Solomon Szyk was a textile factory director, a quiet occupation until June 1905, when, during the so-called Łódź insurrection, one of his workers threw acid in his face, permanently blinding him.

._Portrait_of_Julia_Szyk_(1926)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp)

Szyk showed artistic talent as a child; when he was six years old, he reportedly drew sketches of the Boxer Rebellion in China.[6] Even though his family was culturally assimilated and did not practice Orthodox Judaism, Arthur also liked drawing biblical scenes from the Hebrew Bible. These interests and talents prompted his father, upon the advice of Szyk's teachers, to send Szyk to Paris to study at Académie Julian,[7] a studio school popular among French and foreign students. In Paris, Szyk was exposed to all modern trends in art; however, he decided to follow his own way, which hewed closely to tradition. He was especially attracted by the medieval art of illuminating manuscripts, which greatly influenced his later works. When studying in Paris, Szyk remained closely involved with the social and civic life of Łódź. During the years 1912–1914 the teenage artist produced numerous drawings and caricatures on contemporary political themes that were published in the Łódź satirical magazine Śmiech ("Laughter").

After four years in France, Szyk returned to Poland in 1913 and continued his studies in Teodor Axentowicz's class at Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, which was under Austrian rule at that time. He not only attended lectures and classes, but he also actively participated in Kraków's cultural life. He did not forget his home city Łódź – he designed the stage sets and costumes for the Łódź-based Bi Ba Bo cabaret. The political and national engagement of the artist also deepened during that time – Szyk regarded himself as a Polish patriot but he was also proud of being Jewish and he often opposed antisemitism in his works. At the beginning of 1914, Szyk in a group with other Polish-Jewish artists and writers set off on a journey to Palestine, organized by the Jewish Cultural Society Hazamir (Hebrew: nightingale). There he observed the efforts of Jewish settlers working for the benefit of the future Jewish state.[8]

The visit was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Szyk, who was a Russian subject, had to leave Palestine, which was part of the Ottoman Empire at that time, and go back to his home country in August 1914. He was conscripted into the Russian army and fought at the battle of Łódź in November/December 1914, but at the beginning of 1915, he managed to escape from the army and spent the rest of the war in his home city. He also used the time spent in the Russian army to draw Russian soldiers and published these drawings as postcards in the same year (1915).[9] On September 14, 1916, Arthur Szyk married Julia Likerman. Their son George was born in the following year, and their daughter Alexandra in 1922.

Between the wars

In the Second Polish Republic

._Rewolucja_w_Niemczech_(Revolution_in_Germany)%252C_Valkyrie_(1919)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp)

After Poland had regained independence in 1918, Szyk fully developed his artistic activity, combining it with political engagement. In 1919, influenced by the events of the German Revolution of 1918–19, he published, together with poet Julian Tuwim, his first book of political illustrations: Rewolucja w Niemczech (Revolution in Germany), which was a satire on the Germans, who need the Kaiser's and the military's consent even to start a revolution.[10] In the same year, Szyk had to take part in warfare again – during the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1920), in which he served as a Polish cavalry officer and as the artistic director of the propaganda department of the Polish army in Łódź.[11][12]

In France

In 1921 Arthur Szyk and his family moved to Paris where they stayed until 1933. The relocation to Paris is marked by a breakthrough in the formal aspect of Szyk's works. While Szyk's prior book illustrations were drawings in pen and ink (Szyk had illustrated six books before 1925, including three published in the Yiddish language), the illustrations for the books published in Paris were full colour and full of detail. The first book illustrated in this way was the Book of Esther (Le livre d'Esther, 1925), followed by Gustave Flaubert's dialogue The Temptation of Saint Anthony (La tentation de Saint Antoine, 1926), Pierre Benoît's novel Jacob's Well (Le puits de Jacob, 1927) and other books. Those illustrations, which are characterized by a rich diversity of colours and detailed presentation, deliberately referred to the medieval and renaissance traditions of illumination of manuscripts, often with interspersed contemporary elements. Szyk drew himself as one of the characters in the Book of Esther.. The only stylistic exception is illustrations to the two volume collection of humorous anecdotes about Jews Le juif qui rit (1926/27), in which the artist returned to simple black and white graphics. (Paradoxically, the book, one of the best known of his works, met with criticism as repeating antisemitic stereotypes.) The artist's reputation was also enhanced by exhibitions which were organized by Galeries Auguste Decour (the art gallery first exhibited Szyk's works in 1922). Szyk's drawings were purchased by the Minister of Education and Fine Arts Anatole de Monzie and the New York businessman Harry Glemby.[13]

Szyk had many opportunities to travel for his art. In 1922, he spent seven weeks in Morocco, then a protectorate of France, where he drew the portrait of the pasha of Marrakech – as a goodwill ambassador he received the Ordre des Palmes Académiques from the French government for this work. In 1931 he was invited to the seat of the League of Nations in Geneva, where he began illustrating the statute of the League. The artist made some of the pages of the statute but did not complete that work as a result of his disappointment with the policies of the organization in the 1930s.[14]

._David_and_Saul_(1921)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) David and Saul (1921), Łódź, Poland.

David and Saul (1921), Łódź, Poland.._Pie%C5%9B%C5%84_nad_Pie%C5%9Bniami_(Song_of_Songs)_frontispiece%252C_(c.1924)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) Pieśń nad Pieśniami (Song of Songs) frontispiece, (c. 1924), Łódź, Poland

Pieśń nad Pieśniami (Song of Songs) frontispiece, (c. 1924), Łódź, Poland._La_Ronde_de_Deesses_(The_Circle_of_Godesses)_(1925)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) La Ronde de Deesses (The Circle of Goddesses) (1925), Paris.

La Ronde de Deesses (The Circle of Goddesses) (1925), Paris.._Le_Talisman%252C_The_Lionheart_Lies_in_his_Pavilion_(1927)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Le Talisman, The Lionheart Lies in his Pavilion (1927), Paris.

Le Talisman, The Lionheart Lies in his Pavilion (1927), Paris.._Bar_Kochba_(1927)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Bar Kochba (1927), Paris.

Bar Kochba (1927), Paris.._Pacte_de_la_Soci%C3%A9t%C3%A9_des_Nations_(Covenant_of_the_League_of_Nations)_(1931)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Pacte de la Société des Nations (Covenant of the League of Nations) (1931), Paris.

Pacte de la Société des Nations (Covenant of the League of Nations) (1931), Paris.

Statute of Kalisz and Washington and his Times

During his stay in France, Szyk maintained his ties with Poland. He often visited his home country, illustrated books, and exhibited his works there. During the second half of the 1920s, he mainly illustrated the Statute of Kalisz, a charter of liberties which were granted to the Jews by Bolesław the Pious, the Duke of Kalisz, in 1264.[15] In the years 1926–1928, he created a rich graphic setting of the 45-page-long Statute, showing the contribution of the Jews to Polish society; for example their participation in Poland's pro-independence struggle, during the January Uprising of 1863, and in the Polish Legions in World War I commanded by Józef Piłsudski, to whom Szyk also dedicated his work. The Statute of Kalisz was published in book form in Munich in 1932, but it gained popularity even earlier. Postcards with reproductions of Szyk's illustrations were published in Kraków around 1927. The original art was shown at exhibitions in Warsaw, Łódź and Kalisz in 1929, and a "Traveling Exhibition of Artur Szyk's Works" was held in 1932–1933, displaying the Statute at exhibitions in 14 Polish towns and cities. In recognition of his work, Arthur Szyk was decorated with the Gold Cross of Merit by the Polish government.[16][17]

Another great historical series Szyk created was Washington and his Times, which he began in Paris in 1930. The series, which included 38 watercolours, depicted the events of the American Revolutionary War and was a tribute to the first president of the United States and the American nation in general. The series was presented at an exhibition at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. in 1934. It brought another decoration to Szyk – this time the George Washington Bicentennial Medal from the American government.[18][19]

._Statute_of_Kalisz%252C_frontispiece_(Casimir_the_Great)_(1927)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Statute of Kalisz, frontispiece (Casimir the Great) (1927), Paris.

Statute of Kalisz, frontispiece (Casimir the Great) (1927), Paris.._Statute_of_Kalisz%252C_English_page_(1927)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Statute of Kalisz, English page (1927), Paris.

Statute of Kalisz, English page (1927), Paris.._Statute_of_Kalisz%252C_Jewish_Craftsmen_and_Tradesmen_(1927)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Statute of Kalisz, Jewish Craftsmen and Tradesmen (1927), Paris.

Statute of Kalisz, Jewish Craftsmen and Tradesmen (1927), Paris.._Washington_and_His_Times%252C_Washington_with_His_Soldiers_-_Washington_the_Soldier_(1930)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Washington and His Times, Washington the Soldier (1930), Paris.

Washington and His Times, Washington the Soldier (1930), Paris.._Washington_and_His_Times%252C_The_Struggle_on_Concord_Bridge_(1930)%252C_Paris.jpg.webp) Washington and His Times, The Struggle on Concord Bridge (1930), Paris.

Washington and His Times, The Struggle on Concord Bridge (1930), Paris.

The Haggadah and moving to London.

._Hitler_as_Pharaoh_(c._1933).jpg.webp)

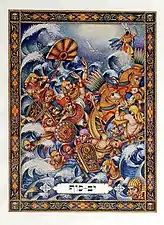

Szyk's art became even more politically engaged when Adolf Hitler took power in Germany in 1933. Szyk started drawing caricatures of Germany's Führer as early as 1933; probably the first was a pencil drawing of Hitler dressed as an ancient Egyptian pharaoh.[20] These drawings anticipated another great series of Szyk's drawings – the Haggadah, which is considered his magnum opus. The Haggadah is a very important and popular story in Jewish culture and religion about the Exodus or departure of the Israelites from ancient Egypt, which is read every year during the Passover Seder.[21] Szyk illustrated the Haggadah in 48 miniature paintings in the years 1934–1936. The antisemitic politics in Germany led Szyk to introduce some contemporary elements to it. For example, he painted the Jewish parable of the Four Sons, in which the "wicked son" was portrayed as a man wearing German clothes, with a Hitler-like moustache and a green Alpine hat. The political intent of the series was even stronger in its original version: he painted upon the red snakes the swastika, the symbol of the Third Reich.

In 1937, Arthur Szyk went to London to supervise the publication of the Haggadah. However, in the three years leading to its publication, the artist had to agree to many compromises, including painting over the swastikas. It is not clear whether he did it under the pressure from his publisher or from British politicians who pursued the policy of appeasement with to Germany. The Haggadah was at last published in 1940, dedicated it to King George VI and with a translation (of the Hebrew) and commentary by British Jewish historian Cecil Roth. The work was widely acclaimed by critics; according to The Times of London Literary Supplement, it was "worthy to be placed among the most beautiful of books that the hand of man has ever produced".[22][23] It was the most expensive new book in the world at the time, with each of the 250 limited edition copies of vellum selling for 100 guineas or US$520.[24]

._The_Haggadah%252C_Dedication_to_King_George_VI_(1936)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) The Haggadah, Dedication to King George VI (1936), Łódź, Poland.

The Haggadah, Dedication to King George VI (1936), Łódź, Poland.._The_Haggadah%252C_The_Family_at_the_Seder_(1935)%252C_Lw%C3%B3w%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) The Haggadah, The Family at the Seder (1935), Łódź, Poland.

The Haggadah, The Family at the Seder (1935), Łódź, Poland.._The_Haggadah%252C_The_Four_Questions_(1935)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) The Haggadah, The Four Questions (1935), Łódź, Poland.

The Haggadah, The Four Questions (1935), Łódź, Poland.._The_Haggadah._The_Four_Sons_(1934)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) The Haggadah. The Four Sons (1934), Łódź, Poland.

The Haggadah. The Four Sons (1934), Łódź, Poland.._The_Haggadah._French_Dedication_Page_(1935)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland.jpg.webp) The Haggadah. French Dedication Page (1935), Łódź, Poland.

The Haggadah. French Dedication Page (1935), Łódź, Poland. The Haggadah, Pharaoh's Army Perishing in the Red Sea.

The Haggadah, Pharaoh's Army Perishing in the Red Sea.

New York World's Fair, 1939

The last major exhibition of Szyk's works before the outbreak of World War II was the presentation of his paintings at the 1939 New York World's Fair, which opened in April 1939 in New York.[25] The Polish Pavilion prominently featured Szyk's twenty-three paintings depicting the contribution of the Poles to the history of the United States; many works specifically highlighted the historic political connections between the two countries, as if to remind the viewer that Poland remained a suitable ally in a turbulent time.. (Twenty of the images were reproduced as postcards in Kraków in 1938 and were available for sale.). In this series, Szyk depicted the contribution of the Poles to the history of the United States, and highlighted historic connections between the two countries.[26]

._Polish-American_Fraternity_series%252C_Tadeusz_Ko%C5%9Bciuszko_(1938)%252C_London.jpg.webp) Polish-American Fraternity series, Tadeusz Kościuszko (1938), London.

Polish-American Fraternity series, Tadeusz Kościuszko (1938), London.._Polish-American_Fraternity_series%252C_Wilson_and_Paderewski_(1939)%252C_Krak%C3%B3w.jpg.webp) Polish-American Fraternity series, Wilson and Paderewski (1939), Kraków.

Polish-American Fraternity series, Wilson and Paderewski (1939), Kraków.

World War II

Reaction to the outbreak of the war

._The_Germain_'Authority'_in_Poland_(1939)%252C_London.jpg.webp)

._The_New_Order_dustjacket_(1941)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp)

The German invasion of Poland found Szyk in Britain where he supervised the publication of the Haggadah and continued to exhibit his works. The artist immediately reacted to the outbreak of World War II by producing war-themed works. One feature which distinguished Szyk from other caricaturists who were active during World War II was that he concentrated on the presentation of the enemy in his works and seldom depicted the leaders or soldiers of the Allies. This was a characteristic feature of Szyk's work till the end of the war.[27] In January 1940, the exhibition of his 72 caricatures entitled War and "Kultur" in Poland opened at the Fine Art Society in London, and was well received by the critics. As the reviewer of The Times wrote:

There are three leading motives in the exhibition: the brutality of the Germans – and the more primitive savagery of the Russians, the heroism of the Poles, and the suffering of the Jews. The cumulative effect of the exhibition is immensely powerful because nothing in it appears to be a hasty judgment, but part of the unrelenting pursuit of an evil so firmly grasped that it can be dwelt upon with artistic satisfaction.[28]

Szyk drew more and more caricatures directed at the Axis powers and their leaders, and his popularity steadily grew. In 1940, the American publisher G.P. Putnam's Sons offered to publish a collection of his drawings. Szyk agreed, and the result was the 1941 book The New Order, available months before the United States joined the war. Thomas Craven declared on the dust jacket of The New Order that Szyk:

...makes not only cartoons but beautifully composed pictures which suggest, in their curiously decorative quality, the inspired illuminations of the early religious manuscripts. His designs are as compact as a bomb, extraordinarily lucid in statement, firm and incisive in line, and deadly in their characterizations. (...) These are remarkable documents.[29]

Some years later, in 1946, art critic Carl Van Doren said of Szyk:

There is no one more certain to be alive two hundred years from now. Just as we turn back to Hogarth and Goya for the living images of their age, so our descendants will turn back to Arthur Szyk for the most graphic history of Hitler and Hirohito and Mussolini. Here is the damning essence of what has happened; here is the piercing summary of what men have thought and felt.

Moving to the United States and war caricatures

._Anti-Christ_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp)

._Collier's_Magazine_front_cover_illustrations_(1942-1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp)

At the beginning of July 1940, with the support of the British government and the Polish government-in-exile, Arthur Szyk left Britain for North America, on assignment to popularize in the New World the struggle of the British and Polish nations against Nazism. His first destination on the continent was Canada, where he was welcomed enthusiastically by the media: they wrote about his engagement in the fight with Nazi Germany, and the Halifax-based Morning Herald even reported about the alleged bounty Hitler had put on Szyk.[30] In December 1940, Szyk and his wife and daughter went to New York City, where he lived till 1945. His son, George, had enlisted in the Free French Forces commanded by General Charles de Gaulle.[31]

Soon after his arrival in the U.S., Szyk was inspired by Roosevelt's 1941 "Four Freedoms" State of the Union speech to illustrate the Four Freedoms, preceding Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms by two years;[32] these were used as poster stamps during the war, and appeared on the Four Freedoms Award which was presented to Harry Truman, George Marshall and Herbert H. Lehman. Szyk became an immensely popular artist in his new home country the war, especially after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the United States into the war. His caricatures of the leaders of the Axis powers (Hitler, Mussolini, Hirohito) and other drawings appeared practically everywhere: in newspapers, magazines (including Time (cover caricature of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in December 1941), Esquire, and Collier's), on posters, postcards and stamps, in secular, religious and military publications, on public and military buildings. He also produced advertisements for Coca-Cola and U.S. Steel, and exhibited in the galleries of M. Knodler & Co., Andre Seligmann, Inc., Messrs. Wildenstein & Co., the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the Brooklyn Museum, the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco, and the White House. More than 25 exhibitions were staged altogether in the United States during the war years. At the end of the war, in 1945, his drawing Two Down and One to Go was used in a propaganda film calling American soldiers to the final assault on Japan. According to the Esquire magazine, the posters with Szyk's drawings enjoyed even bigger popularity with American soldiers than pin-up girls put on the walls of American military bases.[33] In total, more than one million American soldiers saw Szyk's in reproduction at some 500 locations administered by the United Services Organization.[34]

._Satan_Leads_the_Ball_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Satan Leads the Ball (1942), New York.

Satan Leads the Ball (1942), New York.._The_Nibelungen_series%252C_Valhalla_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) The Nibelungen series, Valhalla (1942), New York.

The Nibelungen series, Valhalla (1942), New York.._The_Nibelungen_series%252C_Ride_of_the_Valkyries_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) The Nibelungen series, Ride of the Valkyries (1942), New York.

The Nibelungen series, Ride of the Valkyries (1942), New York.._Fool_the_Axis_Use_Prophylaxis_poster_(1942)%252C_Philadelphia.jpg.webp) Fool the Axis Use Prophylaxis poster (1942), Philadelphia.

Fool the Axis Use Prophylaxis poster (1942), Philadelphia.._In_Comradeship_of_Arms_series%252C_Joan_of_Arc_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) In Comradeship of Arms series, Joan of Arc (1942), New York

In Comradeship of Arms series, Joan of Arc (1942), New York._In_Comradeship_of_Arms_series%252C_King_Jagie%C5%82%C5%82o_of_Poland_(1942)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) In Comradeship of Arms series, King Jagiełło of Poland (1942), New York.

In Comradeship of Arms series, King Jagiełło of Poland (1942), New York.._De_Profundis_(Chicago_Sun)_(1943)%252C_Chicago.jpg.webp) De Profundis - Cain, Where is Abel Thy Brother? as published in the Chicago Sun, 1943.

De Profundis - Cain, Where is Abel Thy Brother? as published in the Chicago Sun, 1943.._To_Be_Shot_as_Dangerous_Enemies_of_the_Third_Reich_(1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) To Be Shot as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich (1943), New York.

To Be Shot as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich (1943), New York.![We're Running Short of Jews (1943), New York. [Dedicated to Szyk's mother who was murdered in the Shoah]](../I/Arthur_Szyk_(1894-1951)._We're_Running_Short_of_Jews_(1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) We're Running Short of Jews (1943), New York. [Dedicated to Szyk's mother who was murdered in the Shoah]

We're Running Short of Jews (1943), New York. [Dedicated to Szyk's mother who was murdered in the Shoah]._Tears_of_Rage_-_Action_Not_Pity_(The_New_York_Times)_(1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Tears of Rage - "Action, Not Pity" as published in The New York Times, 1943.

Tears of Rage - "Action, Not Pity" as published in The New York Times, 1943.._Black%252C_White_and_Jew_in_Common_Cause_(1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Black, White and Jew in Common Cause (1943), New York.

Black, White and Jew in Common Cause (1943), New York.._Save_Human_Lives_poster_stamps_(1944)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Save Human Lives poster stamps (1944), New York.

Save Human Lives poster stamps (1944), New York.._Palestine_Restricted_(reproduced_1946)_(1944)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Palestine Restricted (1944) as reproduced on a 1946 report.

Palestine Restricted (1944) as reproduced on a 1946 report.._Ink_%2526_Blood%252C_Frontispiece_(1944)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Ink & Blood, Frontispiece (1944), New York.

Ink & Blood, Frontispiece (1944), New York.._Two_Down_and_One_to_Go_pamphlet_(1945)%252C_Washington_DC.jpg.webp) Two Down and One to Go pamphlet (1945), Washington DC.

Two Down and One to Go pamphlet (1945), Washington DC.

In recognition for his services in the fight against Nazism, Fascism, and the Japanese aggression, Eleanor Roosevelt, First Lady and wife of President F. D. Roosevelt, wrote about Szyk several times in her newspaper column, My Day.[35] On January 8, 1943, she wrote:

...I had a few minutes to stop in to see an exhibition of war satires and miniatures by Arthur Szyk at the Seligman Galleries on East 57th Street. This exhibition is sponsored by the Writers' War Board. I know of no other miniaturist doing quite this kind of work. In its way it fights the war against Hitlerism as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts today.

Social justice on the home front

Though Szyk was a fierce opponent of Nazi Germany and the rest of the Axis Powers, he did not avoid topics or themes which presented the Allies in a less favourable light. Szyk criticized the United Kingdom for its policies in the Middle East, especially its practice of imposing limits on Jewish emigration to Palestine.[36][37] Szyk also criticized the apparent passivity of American-Jewish organizations towards the tragedy of their European fellows.[38] He supported the work of Hillel Kook, also known as Peter Bergson, a member of the Zionist organization Irgun, who mounted a publicity campaign in American society whose aim was to draw the American public's attention to the fate of the European Jews. Szyk illustrated for example full-page advertisements (sometimes with copy by screenwriter Ben Hecht) which were published in The New York Times. The artist also spoke against racial tensions in the United States and criticized the fact that the black population did not have the same rights as the whites. In one of his drawings, there are two American soldiers – one black and one white – escorting German prisoners of war. When the white one asks the black: "And what would you do with Hitler?", the black one answers: "I would have made him a Negro and dropped him somewhere in the U.S.A."[39]

Szyk's attitude to his mother country, Poland, was very interesting and full of contradictions. Even though he regarded himself both as Jewish and Polish and showed the suffering of the Poles (not only those of Jewish descent) in the Russian-occupied Polish territories in his drawings, even though he benefited from financial support of the Polish government-in-exile (at least at the beginning of the war), Szyk sometimes presented that government in a negative light, especially at the end of World War II. In a controversial drawing dated 1944, a group of debating Polish politicians are shown as opponents of Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin, the "Bolshevik agent" Winston Churchill, and at the same time adherents of Father Charles Coughlin, known for his antisemitic views, as well as "(national) democracy"[40] and "(national) socialism." Around 1943, Szyk, a former participant in the Polish–Soviet War, also completely changed his opinions on the Soviet Union. His drawing from 1944 already depicts outright a soldier of the Moscow-supported People's Army of Poland next to a Red Army soldier, both liberating Poland.[41]

Whatever his political views, in July 1942 Szyk took the time to look after the family of the Polish diplomat and poet General Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski when the General committed suicide. He invited his wife Bronisława Wieniawa-Długoszowska and daughter Zuzanna to stay with his family for six weeks in the country.

._De_Profundis_(Chicago_Sun)_(1943)%252C_Chicago.jpg.webp) De Profundis (Chicago Sun, 1943)

De Profundis (Chicago Sun, 1943)._Tears_of_Rage_-_Action_Not_Pity_(The_New_York_Times)_(1943)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Tears of Rage - Action - Not Pity (The New York Times, 1943)

Tears of Rage - Action - Not Pity (The New York Times, 1943)._We_Must_Ask_Washington_(1944)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) We Must Ask Washington. New York, 1944.

We Must Ask Washington. New York, 1944.

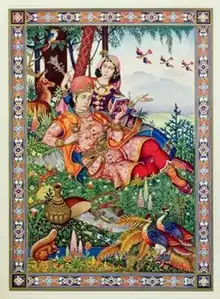

Book illustrations

Even though caricatures dominated Szyk's artistic output during the war, he was still engaged in other areas of art. In 1940, the American publisher George Macy, who saw his illustrations for the Haggadah at an exhibition in London, asked him to illustrate the Rubaiyat, a collection of poems of the Iranian poet Omar Khayyám.[42] In 1943, the artist started work on illustrations for the Book of Job, published in 1946; he also illustrated collections of fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen (Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1945) and Charles Perrault (Mother Goose, which was not published).[43]

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1940), New York.

Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1940), New York.._Andersen's_Fairy_Tales%252C_inside_cover_illustration_(1944)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Andersen's Fairy Tales, inside cover illustration (1944), New York.

Andersen's Fairy Tales, inside cover illustration (1944), New York.._Andersen's_Fairy_Tales%252C_The_King_and_Queen_of_Roses_(1945)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Andersen's Fairy Tales, The King and Queen of Roses (1945), New York.

Andersen's Fairy Tales, The King and Queen of Roses (1945), New York.

Postwar: final years

In 1945, Arthur Szyk and his family moved from New York City to New Canaan, Connecticut where he lived till the end of his life. The end of the war released him from the duty to fight Nazism through his caricatures; a large collection of drawings from the war period was published by the Heritage Press in 1946 in book form as Ink and Blood: A Book of Drawings. The artist returned to book illustrations, working for example on The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer and, most notably, books telling Bible stories, such as Pathways through the Bible by Mortimer J. Cohen (1946), The Book of Job (1946), The Book of Ruth (1947), The Ten Commandments (1947), The Story of Joseph and his Brothers (1949). Some of the books illustrated by Szyk were also published posthumously, including The Arabian Nights Entertainments (1954) and The Book of Esther (1974). He was also commissioned by Canadian entrepreneur and stamp connoisseur, Kasimir Bileski, to create illustrations for the Visual History of Nations (or United Nations) series of stamps; though the project never came to fruition, Szyk did design stamp album frontispieces for more than a dozen countries, including the United States, Poland, the United Kingdom, and Israel.

._The_Canterbury_Tales%252C_The_Manciple_(1945)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) The Canterbury Tales, The Manciple (1945), New York.

The Canterbury Tales, The Manciple (1945), New York.._Visual_History_of_Nations%252C_The_United_States_of_America_(1945)%252C_New_York.jpg.webp) Visual History of Nations, The United States of America (1945), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Visual History of Nations, The United States of America (1945), New Canaan, Connecticut.._Visual_History_of_Nations%252C_Israel_(1948)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) Visual History of Nations, Israel (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Visual History of Nations, Israel (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.._The_Holiday_Series%252C_Rosh_Hashanah_(1948)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) The Holiday Series, Rosh Hashanah (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.

The Holiday Series, Rosh Hashanah (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.._Arabian_Nights_Entertainments%252C_The_Husband_and_the_Parrot_(1948)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) Arabian Nights Entertainments, The Husband and the Parrot (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Arabian Nights Entertainments, The Husband and the Parrot (1948), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Arthur Szyk was granted American citizenship on May 22, 1948, but he reportedly experienced the happiest day in his life eight days earlier: on May 14, the day of the announcement of the Israeli Declaration of Independence.[44] Arthur Szyk commemorated that event by creating the richly decorated illumination of the Hebrew text of the declaration. Two years later, on July 4, 1950, he also exhibited the richly illuminated text of the United States Declaration of Independence. The artist continued to be politically engaged in his country, criticizing the McCarthyism policy (the ubiquitous atmosphere of suspicion and searching for sympathizers of communism in American artistic and academic circles) and signs of racism. One of his well-known drawings from 1949 shows two armed members of Ku Klux Klan approaching a tied-up African American; the caption for the drawing reads, "Do not forgive them, oh Lord, for they do know what they do." Like many outspoken artists of his era, Szyk was suspected by the House Un-American Activities Committee, which accused him of being a member of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee and six other suspicious organizations. Szyk himself, however, repudiated these accusations of alleged sympathy for communism; his son George sent Judge Simon Rifkind a memorandum outlining his father's innocence.[45]

._Do_Not_Forgive_Them%252C_O_Lord%252C_For_They_Do_Know_What_They_Do_(1949)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) "Do Not Forgive Them, O Lord, For They Do Know What They Do!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut.

"Do Not Forgive Them, O Lord, For They Do Know What They Do!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut.._McCarthyism-He_is_Under_Investigation%252C_His_Blood_is_Red_and_His_Heart_is_Left_of_Center_(1949)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) McCarthyism – "He is Under Investigation, His Blood is Red and His Heart is Left of Center!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut.

McCarthyism – "He is Under Investigation, His Blood is Red and His Heart is Left of Center!..." (1949), New Canaan, Connecticut.._The_Book_of_Esther%252C_Szyk_and_Haman_(1950)._New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) The Book of Esther, Szyk and Haman (1950). New Canaan, Connecticut.

The Book of Esther, Szyk and Haman (1950). New Canaan, Connecticut.._Declaration_of_Independence_(1950)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) Declaration of Independence (1950), New Canaan, Connecticut

Declaration of Independence (1950), New Canaan, Connecticut._Thomas_Jefferson's_Oath_(1951)%252C_New_Canaan%252C_CT.jpg.webp) Thomas Jefferson's Oath (1951), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Thomas Jefferson's Oath (1951), New Canaan, Connecticut.

Arthur Szyk died of a heart attack in New Canaan on September 13, 1951.[46] He was eulogized by Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser, who said:

:"Arthur Szyk was a great artist. Endowed by God with a rare sensitivity to beauty and with a rare skill in giving it graphic representation, he used his talents to create a series of works of splendor and magnificence that will live forever in the history of art. But Arthur Szyk was more than a great artist. He was a great man, a champion of justice, a fearless warrior in the cause of every humanitarian endeavor. His art was his tool and he used it brilliantly. It was in his hands a weapon of struggle with which he fought for the causes close to his heart"; and by Judge Simon H. Rifkind, who said: "The Arthur Szyk whom the world knows, the Arthur Szyk of the wondrous color, and of the beautiful design, that Arthur Szyk whom the world mourns today—he is indeed not dead at all. How can he be when the Arthur Szyk who is known to mankind lives and is immortal and will remain immortal as long as the love of truth and beauty prevails among mankind?"[47]

Legacy

_from_-_The_Haggadah%252C_Dedication_to_King_George_VI_(1936)%252C_%C5%81%C3%B3d%C5%BA%252C_Poland_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The immense popularity Szyk enjoyed in the United States and Europe in his lifetime gradually flagged after his death. From the 1960s to the end of the 1980s, the artist's works were seldom exhibited in American museums. This changed in 1991 when the non-profit organization The Arthur Szyk Society was established in Orange County, California. The founder of the Society, George Gooche, rediscovered Szyk's works and staged the exhibition "Arthur Szyk – Illuminator" in Los Angeles. In 1997, the seat of the Society was transferred to Burlingame, California, and a new Board of Trustees was elected, headed by rabbi, curator and antiquarian Irvin Ungar. The Society's work resulted in staging many exhibitions of Szyk's works in American cities in the 1990s and 2000s. The Society also maintains a large educational website,[48] holds lectures, and produces publications on the artist. In April 2017, the Ungar collection of his work, consisting of 450 paintings, drawings and sketches, was purchased for $10.1 million by the University of California, Berkeley's Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, through a donation by Taube Philanthropies, the largest single monetary gift to acquire art in UC Berkeley history.[49][50]

Szyk's recent solo exhibitions include:

- "Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art", New-York Historical Society, New York City (September 15, 2017 - January 21, 2018)[51]

- "Arthur Szyk and the Art of the Haggadah", Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco (February 13 to June 29, 2014)

- "Arthur Szyk: Miniature Paintings and Modern Illuminations", California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco (December 10, 2010 to March 27, 2011)

- "A One-Man Army: The Art of Arthur Szyk", Holocaust Museum Houston (October 20, 2008 – February 8, 2009)

- "Arthur Szyk – Drawing Against National Socialism and Terror",[52] Deutsches Historisches Museum (DHM), Berlin, Germany (August 29, 2008 – January 4, 2009)

- "The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. (April 10 – October 14, 2002)

- "Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom", Library of Congress (December 9, 1999 – May 6, 2000)

- "Justice Illuminated: The Art of Arthur Szyk", Spertus Institute for Jewish Learning and Leadership, Chicago (August 16, 1998 – February 28, 1999)[53] —later traveled throughout Poland: Warsaw, Jewish Historical Institute; Łódź, Museum of the City of Łódź; and Kraków, Center for Jewish Culture.

- "In Real Times. Arthur Szyk: Art & Human Rights (1926-1951)" The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, University of California, Berkeley (January 28, 2020 – present)[54]

Notes

- Miller, Rhoda (16 November 2017). "Documents as a Palette of Life: The Genealogical Self-Portrait of Arthur Szyk". The Arthur Szyk Society Art History Publication Series (4): 2.

- "Szyk, Arthur : Benezit Dictionary of Artists - oi". oxfordindex.oup.com. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00178831. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Ansell, Joseph P. Arthur Szyk: Artist, Jew, Pole. Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004. p. 5

- Ansell, p. 7

- The artist's birth name was Artur Szyk, but in Western Europe and the United States he is commonly known as Arthur Szyk, which is also how he usually signed his works.

- Current Biography, New York, 1946, p. 588.

- "About Arthur Szyk > Early Years | Szyk.com". szyk.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- Irvin Ungar : Arthur Szyk : Soldier in Art, in: Arthur Szyk : Drawing against National Socialism and Terror, German Historical Museum, Berlin, 2008, pp. 12-15.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing against National Socialism and Terror, German Historical Museum, Berlin, 2008, pp. 74-75.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 72-73.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 15-16.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 76-77.

- I. Ungar, op. cit. , pp. 16-18.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 90-91.

- Ansell, Joseph P. "Art against Prejudice: Arthur Szyk's Statute of Kalisz." The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 14 (1989): 47-63. doi:10.2307/1504027.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 18-19.

- The original paintings for the Statute are now in the Jewish Museum in New York City.

- I. Ungar, op. cit. , pp. 19-20.

- Washington and his Times was published in book form in Vienna in 1932. The originals of the watercolours were presented by the President of Poland Ignacy Mościcki to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935. They are now stored at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 100-101.

- Schochet, Dovie. "The Haggadah". www.chabad.org. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "The Szyk Haggadah > Overview | Szyk.com". szyk.com. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- I. Ungar, op. cit. pp. 19-23.

- Ansell, p. 111

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 88-89.

- Ansell, p. 118

- I. Ungar, op. cit., p. 23.

- Polish War Satires : Miniatures by Mr Szyk, in: The Times, January 11, 1940.

- Arthur Szyk, The New Order, New York, 1941.

- The Morning Herald, July 13, 1940. The information about the alleged bounty was also repeated by American media, but it is not confirmed by reliable sources.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 23-25.

- "Visualizing the Four Freedoms: FDR's Fighting Artist Arthur Szyk" by Allison Claire Chang, The Nation, January 8, 2016 (online only)

- The Answer, New York, September 1945, p. 14.

- Ansell, 147.

- Black, Allida M. (editor); Binker, Mary Jo (associate editor); Alhambra, Christopher C. (electronic text editor) (June 4, 2007). "My Day by Eleanor Roosevelt". Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Hyde Park, N.Y. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

{{cite web}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - Despite the fact that the British government had provided for the creation of a Jewish state in the Balfour Declaration, in May 1939, the House of Commons passed the so-called White Paper, which limited the number of Jewish immigrants to the Holy Land to 10,000 yearly, a policy that had tragic consequences for the Jews in Hitler-occupied Europe.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., p. 26.

- The rescue of European Jewry was personal for Szyk: his mother and his brother were in the ghettos of Łódź. (Ultimately Szyk's mother, Eugenia Szyk, and possibly her Polish-Christian companion, was murdered at the Chełmno extermination camp in 1942. See Luckert, The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk, 103.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 25-26.

- Szyk alludes to the National Democracy, a pre-war right-wing political movement in Poland, known for its nationalistic and antisemitic views.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 27-28.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 64-65.

- Arthur Szyk : Drawing..., pp. 68-69.

- Compare the memoirs of Julia Szyk, the artist's wife, who recorded her husband's reaction to that event. Her memoirs are kept by The Arthur Szyk Archives in Burlingame, California.

- Ansell. p232.

- I. Ungar, op. cit., pp. 29-31.

- "The Arthur Szyk Society – Eulogies and Tributes". Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "チルコレ". szyk.org. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Magnes museum gets big collection of Jewish art, thanks to Taube - SFGate". 3 April 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Largest single monetary gift to acquire art in UC Berkeley history brings work of major 20th-century artist to campus". Berkeley News. April 3, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art". New-York Historical Society Museum & Library. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin". www.dhm.de. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Justice Illuminated: The Art of Arthur Szyk" is a traveling exhibition of The Arthur Szyk Society. Compare the Society's website About the Arthur Szyk Society Archived November 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- "In Real Times. Arthur Szyk: Art & Human Rights (1926-1951) - The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life". 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

Bibliography

- Irvin Ungar and Samantha Lyons, Arthur Szyk Preserved: Institutional Collections of Original Art, London : D Giles Limited in association with Historicana, 2023, ISBN 978-1913875404.

- Irvin Ungar, Michael Berenbaum, Tom L. Freudenheim, and James Kettlewell, Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art, London : D Giles Limited in association with Historicana and The Arthur Szyk Society, 2017, ISBN 978-1911282082.

- Byron L. Sherwin and Irvin D. Ungar, Freedom Illuminated: Understanding The Szyk Haggadah, Burlingame, Historicana, 2008, ISBN 978-0979954610.

- Katja Widmann and Johannes Zechner. Arthur Szyk : Drawing against National Socialism and Terror, Berlin : Deutsches Historisches Museum, 2008, ISBN 978-3-86102-151-3.

- Joseph Ansell, Artur Szyk : Artist, Jew, Pole, Oxford, Portland, Or. : Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004, ISBN 1-874774-94-3.

- Stephen Luckert, The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk, Washington, D.C.: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2002, ISBN 978-0896047082.

- Irvin Ungar, Justice Illuminated : the Art of Arthur Szyk, Chicago : Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies, 1998, ISBN 978-1583940105.

- "Arthur Szyk - Soldier in Art: Rare Polish Poster from World War II Discovered" by Zbigniew Kantorosinski with Joseph P. Ansell, The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, September 5, 1994, p. 329.

- Samuel L. Shneiderman, Arthur Szyk, Tel Aviv : I. L. Peretz Publishing House, 1980 (in Hebrew).

External links

![]() Media related to Arthur Szyk at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arthur Szyk at Wikimedia Commons

- Arthur Szyk – Illuminator, Activist, Master

- Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art exhibition at the New-York Historical Society

- Arthur Szyk – Drawing against National Socialism and Terror exhibition at the German Historical Museum

- The Art and Politics of Arthur Szyk exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- The Beauty & Anti-Nazi Message of Artur Szyk's Haggadah

- Arthur Szyk's drawings in American Art Archives

- Guide to the Arthur Szyk (1894–1951) Collection at the American Jewish Historical Society, New York.