Ascalon

Ascalon (Philistine: 𐤀𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍, romanized: *ʾAšqalōn;[1] Hebrew: אַשְׁקְלוֹן, romanized: ʾAšqəlōn; Koinē Greek: Ἀσκάλων, romanized: Askálōn; Latin: Ascalon; Arabic: عَسْقَلَان, romanized: ʿAsqalān) was an ancient Near East port city on the Mediterranean coast of the southern Levant that played several major roles in history.

𐤀𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍 אַשְׁקְלוֹן Ἀσκάλων عَسْقَلَان | |

.jpg.webp) Remains of the Church of Santa Maria Viridis | |

Ascalon Shown within Israel | |

| Location | Southern District, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia, Middle East |

| Coordinates | 31°39′43″N 34°32′46″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 2000 BCE |

| Abandoned | 1270 CE |

| Periods | Bronze Age to Crusades |

| Cultures | Philistine(?), Crusaders |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1815 |

| Archaeologists | Lady Hester Stanhope |

The site of Ascalon was first permanently settled in the Middle Bronze Age, and, over a period of several thousand years, was the site of several settlements called "Ascalon", or some variation thereof. During the Iron Age, Ascalon served as the oldest and largest seaport in Canaan, and as one of the five cities of the Philistine pentapolis, lying north of Gaza and south of Jaffa. The city remained a major metropolis throughout antiquity and the early Middle Ages, before becoming a highly contested fortified foothold on the Palestinian coast during the Crusades. In the later medieval period, the city was the site of two significant Crusader battles: the Battle of Ascalon in 1099, and the Siege of Ascalon in 1153.

The ancient and medieval history of Ascalon was brought to an end in 1270, when the then Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed, though some monuments, such as the Shrine of Husayn's Head survived. The town of al-Majdal, Askalan was established in the same period.[2] Ottoman tax records attest the existence of the village of Al-Jura adjacent to citadel walls from at least 1596.[3] That residual settlement survived until its depopulation in 1948.

The modern Israeli city of Ashkelon takes its name from the site, but it was established at the site of al-Majdal, Askalan, the town established nearby in the Mamluk period.

Names

Ascalon has been known by many variations of the same basic name over the millenia. The settlement is first mentioned in the Egyptian Execration Texts of the 11th dynasty as Asqalānu.[1] In the Amarna letters (c. 1350 BC), there are seven letters to and from King Yidya of Ašqaluna and the Egyptian pharaoh. The Merneptah Stele of the 19th dynasty recounts the Pharaoh putting down a rebellion at Asqaluna.[4] The settlement is then mentioned eleven times in the Hebrew Bible as ʾAšqəlôn.[1]

In the Hellenistic period, "Ascalon" or "Askalon" emerged as the Ancient Greek name for the city,[5] persisting through the Roman period and later Byzantine period.[6][7][8] In the Islamic period, the transliterated Arabic form became Asqalan,[9] while in modern Hebrew, it became "Ashkelon". Today, Ascalon is a designated archaeological area known as Tel Ashkelon.

History

Neolithic period

About 1.5 kilometres (1 mi) north of the ruins of Ascalon lies a Neolithic site dating habitation in the area to c. 7900 BP in the pre-pottery phase of the Neolithic. The adjacent site had no built structures and was believed to have been used seasonally by pastoral nomads for processing and curing food.

Canaanite settlement

.jpg.webp)

The first constructed settlement was hewn into the sandstone outcrop along the coast in the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BCE). A relatively large and thriving settlement for the period, its walls enclosed 60 hectares (150 acres) and as many as 15,000 people may have lived within these fortifications.

Its commanding ramparts measured 2.5 kilometres (1+1⁄2 mi) long, 15 m (50 ft) high and 45 m (150 ft) thick, and even as a ruin they stand two stories high. The thickness of the walls was so great that the mudbrick city gate had a stone-lined, 2.4-metre-wide (8 ft) tunnel-like barrel vault, coated with white plaster, to support the superstructure: it is the oldest such vault ever found.[10]

In the early MB IIA, the Egyptians mainly sent their ships further north to Lebanon (Byblos). In the late MB IIA, the settlement phases 14-10 can be compared with Tell ed-Dab'a stratums H-D/1. Contacts with Egypt increased in the late 12th Dynasty and early 13th Dynasty when maritime trade flourished.

Ascalon is mentioned in the Egyptian Execration Texts of the 11th dynasty as "jsqꜣnw".[1]

Egyptian period

ny.gif)

Beginning in the time of Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) the city was under Egyptian control, administered by a local governor. In the Amarna letters (c. 1350 BC), there are seven letters to and from King Yidya of Ašqaluna and the Egyptian pharaoh.

During the reign of Ramesses II the Southern Levant was the frontier of the epic war against the Hittites in Syria. In addition, the Sea Peoples attacked and rebellions occurred. These events coincide with a downturn in climatic conditions starting around 1250 BC onwards, ultimately causing the Late Bronze Age collapse. On the death of Ramesses II, turmoil and rebellion increased in the Southern Levant. The king Merneptah faced a series of uprisings, as told in the Merneptah Stele. The Pharaoh notes putting down a rebellion at "'Asqaluni".[11] Further north, the King Jabin of Hazor tried to fight for independence with Mycenaean mercenaries - Merneptah laying waste the grain fields in the Valley of Yizreel to starve out the northern rebellion. These events contributed to the fall of the 19th dynasty.

Philistine settlement

The Philistines conquered the Canaanite city in about 1150 BCE. Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre at Mycenae in mainland Greece, adding weight to the hypothesis that the Philistines were one of the populations among the "Sea Peoples" that upset cultures throughout the Eastern Mediterranean at that time.

In this period, the Hebrew Bible presents Ašqəlôn as one of the five Philistine cities that are constantly warring with the Israelites. According to Herodotus, the city's temple of Venus was the oldest of its kind, imitated even in Cyprus, and he mentions that this temple was pillaged by marauding Scythians during the time of their sway over the Medes (653–625 BCE). It was the last of the Philistine cities to hold out against Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II. When it fell in 604 BCE, burnt and destroyed and its people taken into exile, the Philistine era was over.

Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods

Until the conquest of Alexander the Great, the city's inhabitants were influenced by the dominant Persian culture. It is in this archaeological layer that excavations have found dog burials. It is believed the dogs may have had a sacred role; however, evidence is not conclusive. After the conquest of Alexander in the 4th century BCE, Ashkelon was an important free city and Hellenistic seaport.

It had mostly friendly relations with the Hasmonean kingdom and the Herodian kingdom of Judea, in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE. In a significant case of an early witch-hunt, during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra, the court of Simeon ben Shetach sentenced to death eighty women in Ashkelon who had been charged with sorcery.[12] Herod the Great, who became a client king of the Roman Empire, ruling over Judea and its environs in 30 BCE, had not received Ashkelon, yet he built monumental buildings there: bath houses, elaborate fountains and large colonnades.[13][14] A discredited tradition suggests Ashkelon was his birthplace.[15] In 6 CE, when a Roman imperial province was set in Judea, overseen by a lower-rank governor, Ashkelon was moved directly to the higher jurisdiction of the governor of Syria province.

Roman and Islamic era fortifications, faced with stone, followed the same footprint as the earlier Canaanite settlement, forming a vast semicircle protecting the settlement on the land side. On the sea it was defended by a high natural bluff. A roadway more than six metres (20 ft) in width ascended the rampart from the harbor and entered a gate at the top.

The city remained loyal to Rome during the Great Revolt, 66–70 CE.

Byzantine period

.jpg.webp)

The city of Ascalon appears on a fragment of the 6th-century Madaba Map.[16]

The bishops of Ascalon whose names are known include Sabinus, who was at the First Council of Nicaea in 325, and his immediate successor, Epiphanius. Auxentius took part in the First Council of Constantinople in 381, Jobinus in a synod held in Lydda in 415, Leontius in both the Robber Council of Ephesus in 449 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451. Bishop Dionysius, who represented Ascalon at a synod in Jerusalem in 536, was on another occasion called upon to pronounce on the validity of a baptism with sand in waterless desert. He sent the person to be baptized in water.[17][18]

No longer a residential bishopric, Ascalon is today listed by the Catholic Church as a titular see.[19]

Early Islamic period

During the Muslim conquest of Palestine begun in c. 633–634, Ascalon (called Asqalan by the Arabs) became one of the last Byzantine cities in the region to fall.[9] It may have been temporarily occupied by Amr ibn al-As, but definitively surrendered to Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan (who later founded the Umayyad Caliphate) not long after he captured the Byzantine district capital of Caesarea in c. 640.[9] The Byzantines reoccupied Asqalan during the Second Muslim Civil War (680–692), but the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705) recaptured and fortified it.[9] A son of Caliph Sulayman (r. 715–717), whose family resided in Palestine, was buried in the city.[20] An inscription found in the city indicates that the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi ordered the construction of a mosque with a minaret in Asqalan in 772.[9]

Asqalan prospered under the Fatimid Caliphate and contained a mint and secondary naval base.[9] Along with a few other coastal towns in Palestine, it remained in Fatimid hands when most of Islamic Syria was conquered by the Seljuks.[9] However, during this period, Fatimid rule over Asqalan was periodically reduced to nominal authority over the city's governor.[9]

Shrine of Husayn's Head

In 1091, a couple of years after a campaign by grand vizier Badr al-Jamali to reestablish Fatimid control over the region, the head of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) was "rediscovered", prompting Badr to order the construction of a new mosque and mashhad (shrine or mausoleum) to hold the relic, known as the Shrine of Husayn's Head.[21][22][23] According to another source, the shrine was built in 1098 by the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah.[24]

The mausoleum was described as the most magnificent building in Asqalan.[25] In the British Mandate period it was a "large maqam on top of a hill" with no tomb, but a fragment of a pillar showing the place where the head had been buried.[26] In July 1950, the shrine was destroyed at the instructions of Moshe Dayan in accordance with a 1950s Israeli policy of erasing Muslim historical sites within Israel,[27] and in line with efforts to expel the remaining Palestinian Arabs from the region.[28] Prior to its destruction, the shrine was the holiest Shi'a site in Palestine.[29] In 2000, a marble dais was built on the site by Mohammed Burhanuddin, an Indian Islamic leader of the Dawoodi Bohras.[30]

Crusaders, Ayyubids, and Mamluks

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as Ascalon) was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post.[24] The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[31] Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year.[24] According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers.[24] The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan.[24] In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress.[32]

.jpg.webp)

Three years later, after a seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem.[24] The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum outside the city and transported it to their capital Cairo.[24] Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Jewish community in Ascalon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ascalon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.[33]

In 1187, Saladin took Ascalon as part of his conquest of the Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ascalon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ascalon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule.

The ancient and medieval history of Ascalon was brought to an end in 1270, when the then Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed as part of a wider decision to destroy the Levantine coastal towns in order to forestall future Crusader invasions. Some monuments, like the shrine of Sittna Khadra and Shrine of Husayn's Head survived. According to Marom and Taxel, this event irreversibly changed the settlement patterns in the region. As a substitute for ‘Asqalān, Baybars established Majdal ‘Asqalān, 3 km inland, and endowed it with a magnificent Friday Mosque, a marketplace and religious shrines.[34]

Modern period

Ottoman tax records attest the existence of the village of Al-Jura adjacent to citadel walls from at least 1596. It had 46 Muslim households, an estimated population of 253.[35] The Syrian Sufi teacher and traveller Mustafa al-Bakri al-Siddiqi (1688–1748/9) visited Al-Jura in the first half of the eighteenth century, before leaving for Hamama.[36]

In 1863 the French explorer Victor Guérin visited the village, and found it to have three hundred inhabitants. He further noted that he could see numerous antiquities, taken from the ruined city, and that the inhabitants of the village grew handsome fruit trees, as well as flowers and vegetables.[37] An Ottoman village list from about 1870 found that the village had a population of 340, in a total of 109 houses, though the population count included men, only.[38][39]

In the late nineteenth century, the village of Al-Jura was situated on flat ground bordering on the ruins of ancient Ascalon.[40] It was rectangular in shape and the residents were Muslim. They had a mosque and a school which was founded in 1919.[36]

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Jura had a population of 1,326 inhabitants,[41] increasing in the 1931 census to 1,754 in a total of 396 houses.[42]

In the 1945 statistics El Jura had a population of 2,420 Muslims,[43] with a total of 12,224 dunams of arable land,[44] and 45 dunams were built-up land.[45] In the 1940s, it also had a school had 206 students.[36]

In November 1948, Al-Jura was one of the villages south of Al-Majdal named in the orders to the IDF battalions and engineers platoon to have its residents expelled, with the perpetrating troops "to prevent their return by destroying their villages".[46] In 1992, "only one of the village houses" was described as still visible at the site.[47]

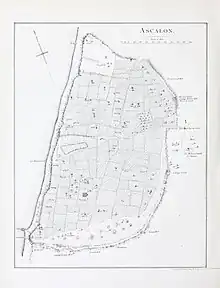

Archaeology

Beginning in the 18th century, the site was visited, and occasionally drawn, by a number of adventurers and tourists. It was also often scavenged for building materials. The first known excavation occurred in 1815. The Lady Hester Stanhope dug there for two weeks using 150 workers. No real records were kept.[48] In the 1800s some classical pieces from Ascalon (though long thought to be from Thessaloniki) were sent to the Ottoman Museum.[49] From 1920 to 1922 John Garstang and W. J. Phythian-Adams excavated on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund. They focused on two areas, one Roman and the other Philistine/Canaanite.[50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57] Over the following years a number of salvage excavations were carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority.[58]

In 1954 by French archaeologist Jean Perrot, discovered a Neolithic site 1.5 kilometres (1 mi) to the north dated by Radiocarbon dating to c. 7900 BP (uncalibrated), to the poorly known Pre-Pottery Neolithic C phase of the Neolithic. In 1997–1998, a large scale salvage project was conducted at the site by Yosef Garfinkel that discovered more than a hundred fireplaces and hearths and numerous pits, with various phases of occupation were found, one atop the other, with sterile layers of sea sand between them, indicating that the site was occupied on a seasonal basis. The excavations also found around 100,000 animal bones belonging to domesticated and non-domesticated animals, and around 20,000 flint artifacts. It was concluded that the site was used by pastoral nomads for meat processing, with the nearby sea supplying salt for the curing of meat.

Modern excavation began in 1985 with the Leon Levy Expedition. Between then and 2006 seventeen seasons of work occurred, led by Lawrence Stager of Harvard University.[59][60][61][62][63][64][65] In 2007 the next phase of excavation began under Daniel Master. It continued until 2016.

In 1991 the ruins of a small ceramic tabernacle was found a finely cast bronze statuette of a bull calf, originally silvered, ten centimetres (4 in) long. Images of calves and bulls were associated with the worship of the Canaanite gods El and Baal.

In the 1997 season a cuneiform table fragment was found, being a lexical list containing both Sumerian and Canaanite language columns. It was found in a Late Bronze Age II context, about 13th century BC.[66]

In 2012 an Iron Age IIA Philistine cemetery was discovered outside the city. In 2013 200 graves were excavated of the estimated 1,200 the cemetery contained. Seven were stone built tombs.[67]

One ostracon and 18 jar handles were recovered inscribed with the Cypro-Minoan script. The ostracon was of local material and dated to 12th to 11th century BC. Five of the jar handles were manufactured in coastal Lebanon, two in Cyprus, and one locally. Fifteen of the handles were found in an Iron I context and the rest in Late Bronze Age context.[68]

Notable people

- Antiochus of Ascalon (125–68 BC), Platonic philosopher

- Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (1372–1449), Islamic hadith scholar

References

- Huehnergard, John (2018). "The Name Ashkelon". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. 33: 91–97. JSTOR 26751887.

- Marom, Roy; Taxel, Itamar (2023-10-01). "Ḥamāma: The historical geography of settlement continuity and change in Majdal 'Asqalan's hinterland, 1270–1750 CE". Journal of Historical Geography. 82: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2023.08.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 150. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 116

- REDFORD, DONALD B. "The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stela." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 36, no. 3/4, 1986, pp. 188–200

- "Ascalon". Oxford Reference.

- Le Blanc, R. (2016). "The Public Sacred Identity of Roman Ascalon".

- Hakim, B. S. (2001). "Julian of Ascalon's Treatise of Construction and Design Rules from Sixth-Century Palestine". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 60 (1): 4–25. doi:10.2307/991676.

- Anevlavi, V.; Cenati, C.; Prochaska, W. (2022). "The marbles of the basilica of Ascalon: another example of the Severan building projects". Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences. 14 (53). doi:10.1007/s12520-022-01518-1.

- Hartmann & Lewis 1960, p. 710.

- Lefkovits, Etgar (8 April 2008). "Oldest arched gate in the world restored". The Jerusalem Post. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 14 August 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- REDFORD, DONALD B. "The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stela." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 36, no. 3/4, 1986, pp. 188–200

- Yerushalmi Sanhedrin, 6:6.

- "Ashkelon". Project on Ancient Cultural Engagement/Brill. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Negev, A (1976). Stillwell, Richard.; MacDonald, William L.; McAlister, Marian Holland (eds.). The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Eusebius (1890). "VI". In McGiffert, Arthur Cushman (ed.). The Church History of Eusebius. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, series II. §2, notes 90-91.

- Donner, Herbert (1992). The Mosaic Map of Madaba. Kok Pharos Publishing House. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-90-3900011-3. quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

- Bagatti, Ancient Christian Villages of Judaea and Negev, quoted in The Madaba Mosaic Map: Ascalon

- Pius Bonifacius Gams, Series episcoporum Ecclesiae Catholicae, Leipzig 1931, p. 452

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 840

- Lecker 1989, p. 35, note 109.

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9781474421522.

- Talmon-Heller, Daniella (2020). "Part I: A Sacred Place: The Shrine of al-Husayn's Head". Sacred Place and Sacred Time in the Medieval Islamic Middle East: An Historical Perspective. University Press Scholarship Online. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9781474460965.001.0001. ISBN 9781474460965. S2CID 240874864.

- M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Shrine". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- Hartmann & Lewis 1960, p. 711.

- Gil, Moshe (1997) [1983]. A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Translated by Ethel Broido. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–194. ISBN 0-521-59984-9.

- Canaan, 1927, p. 151

- Meron Rapoport, 'History Erased,' Haaretz, 5 July 2007.

- Talmon-Heller, Kedar & Reiter 2016.

- Petersen 2017, p. 108.

- Talmon-Heller, Daniella; Kedar, Benjamin; Reiter, Yitzhak (Jan 2016). "Vicissitudes of a Holy Place: Construction, Destruction and Commemoration of Mashhad Ḥusayn in Ascalon" (PDF). Der Islam. 93: 11–13, 28–34. doi:10.1515/islam-2016-0008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020.

- Hartmann & Lewis 1960, pp. 710–711.

- Gore, Rick (January 2001). "Ancient Ashkelon". National Geographic.

- Alex Carmel, Peter Schäfer and Yossi Ben-Artzi (1990). The Jewish Settlement in Palestine, 634–1881. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients : Reihe B, Geisteswissenschaften; Nr. 88. Wiesbaden: Reichert. p. 24,31.

- Marom, Roy; Taxel, Itamar (2023-10-01). "Ḥamāma: The historical geography of settlement continuity and change in Majdal 'Asqalan's hinterland, 1270–1750 CE". Journal of Historical Geography. 82: 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2023.08.003. ISSN 0305-7488.

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 150. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 116

- Khalidi 1992, p. 116.

- Guérin, 1869, p. 134

- Socin, 1879, p. 153 Also noted it in the Gaza district, northeast of Askalon

- Hartmann, 1883, p. 130, also noted 109 houses

- Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, p. 236. Quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 116

- Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p. 8

- Mills, 1932, p. 4

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 31

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 46

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 137

- Coastal Plain District HQ to battalions 151 and ´1 Volunteers`, etc., 19:55 hours, 25 Nov. 1948, IDFA (=Israeli Defence Forces and Defence Ministry Archive) 6308\49\\141. Cited in Morris, 2004, p. 517

- Khalidi 1992, p. 117.

- Charles L. Meryon, Travels of Lady Hester Stanhope. 3 vols. London: Henry Colburn, 1846

- Edhem Eldem. "Early Ottoman Archaeology: Rediscovering the Finds of Ascalon (Ashkelon), 1847." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 378, 2017, pp. 25–53, https://doi.org/10.5615/bullamerschoorie.378.0025

- John Garstang, "The Fund's Excavation of Ashkalon", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 12–16, 1921

- John Garstang, "The Fund's Excavation of Askalon, 1920-1921", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 73–75, 1921

- John Garstang, "Askalon Reports: The Philistine Problem", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 162–63, 1921

- John Garstang, "The Excavations at Ashkalon", PEFQS, vol. 54, pp. 112–19, 1922

- John Garstang, "Ashkalon", PEFQS, vol. 56, pp. 24–35, 1924

- W. J. Phythian-Adams, "History of Askalon", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 76–90, 1921

- W. J. Phythian-Adams, "Askalon Reports: Stratigraphical Sections", PEFQS, vol. 53, pp. 163–69, 1921

- W. J. Phythian-Adams, "Report on the Stratification of Askalon", PEFQS, vol. 55, pp. 60–84, 1923

- Yaakov Huster, Daniel M. Master, and Michael D. Press, "Ashkelon 5 The Land behind Ashkelon", Eisenbrauns, 2015 ISBN 978-1-57506-952-4

- Daniel M. Master, J. David Schloen, and Lawrence E. Stager, "Ashkelon 1 Introduction and Overview (1985-2006)", Eisenbrauns, 2008 ISBN 978-1-57506-929-6

- Barbara L. Johnson, "Ashkelon 2 Imported Pottery of the Roman and Late Roman Periods", Eisenbrauns, 2008 ISBN 978-1-57506-930-2

- Daniel M. Master, J. David Schloen, and Lawrence E. Stager, "Ashkelon 3 The Seventh Century B.C.", Eisenbrauns, 2011 ISBN 978-1-57506-939-5

- Michael D. Press, "Ashkelon 4 The Iron Age Figurines of Ashkelon and Philistia", Eisenbrauns, 2012 ISBN 978-1-57506-942-5

- Lawrence E. Stager, J. David Schloen, and Ross J. Voss, "Ashkelon 6 The Middle Bronze Age Ramparts and Gates of the North Slope and Later Fortifications", Eisenbrauns, 2018 ISBN 978-1-57506-980-7

- Lawrence E. Stager, Daniel M. Master, and Adam J. Aja, "Ashkelon 7 The Iron Age I", Eisenbrauns, 2020 ISBN 978-1-64602-090-4

- Tracy Hoffman, "Ashkelon 8 The Islamic and Crusader Periods", Eisenbrauns, 2019 ISBN 978-1-57506-735-3

- Huehnergard, John, and Wilfred van Soldt. "A Cuneiform Lexical Text from Ashkelon with a Canaanite Column." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 49, no. 3/4, 1999, pp. 184–92

- Daniel M. Master, and Adam J. Aja. "The Philistine Cemetery of Ashkelon." Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 377, 2017, pp. 135–59, https://doi.org/10.5615/bullamerschoorie.377.0135

- Cross, Frank Moore, and Lawrence E. Stager. "Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions Found in Ashkelon." Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, 2006, pp. 129–159

Sources

- Hartmann, R. & Lewis, B. (1960). "Askalan". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 710–711. OCLC 495469456.

- Khalidi, W. (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Washington D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- Lecker, Michael (1989). "The Estates of 'Amr b. al-'Āṣ in Palestine: Notes on a New Negev Arabic Inscription". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 52 (1): 24–37. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00023041. JSTOR 617911. S2CID 163092638.

- Petersen, A. (2017). "Shrine of Husayn's Head". Bones of Contention: Muslim Shrines in Palestine. Heritage Studies in the Muslim World. Springer Singapore. ISBN 978-981-10-6965-9. Retrieved 2023-01-06.