Assyrian continuity

Assyrian continuity is the study of continuity between the modern Assyrian people, a Semitic indigenous ethnic minority in the Middle East, and the people of ancient Assyria and Mesopotamia specifically. Assyrian continuity is a key part of the identity of the modern Assyrian people.[1] No archaeological, genetic, linguistic or written historical evidence exists of the original Assyrian and Mesopotamian population being exterminated, removed or replaced in the aftermath of the fall of the Assyrian Empire,[2] modern contemporary scholarship "almost unilaterally" supports Assyrian continuity, recognizing the modern Assyrians as the ethnic, linguistic and genetic descendants of the East Assyrian-speaking population of Bronze Age and Iron Age Assyria, and Mesopotamia in general,[2][3][4][5] which were composed of both the old native Assyrian population[2][3][5] and of neighbouring settlers in the Assyrian heartland.[2][lower-alpha 1]

_year_6769_(April_1st_2019)_in_Duhok_(Nohaadra)_07.jpg.webp)

Due to a long-standing shortage of historical sources beyond the Bible and some inaccurate works by classical authors, many western historians prior to the early 19th century believed Assyrians to have been completely annihilated. Modern Assyriology has increasingly and successfully challenged this perception; today, Assyriologists and historians recognize that Assyrian culture and people clearly survived the violent fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The last period of ancient Assyrian history is now regarded to be the long post-imperial period, during which the Akkadian language gradually went extinct but other aspects of Assyrian culture, such as religion, traditions, and naming patterns, survived in a reduced but highly recognizable form before giving way to Christianity.[8]

The extinction of Akkadian and its replacement with Aramaic does not reflect the disappearance of the original Assyrian population;[2] Aramaic was used not only by settlers but was also adopted by native Assyrians and Babylonians,[3] in time even becoming used by the royal administration itself.[9][10] In fact, the new language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the Imperial Aramaic, was itself a creation of the empire and its people, and with its retention of an Akkadian grammatical structure and Akkadian words, is distinct from the Western Aramaic of the Levant.[11] Due to assimilation efforts encouraged by Assyrian kings, fellow Semitic Arameans, Israelites, Phoenicians and other groups in the Assyrian heartland are also likely to quickly have been absorbed, self-identified, and been regarded, as Assyrians.[2] The population of Upper Mesopotamia was largely Christianized between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, with Mesopotamian religion enduring among Assyrians in small pockets until the late Middle Ages. Assyrian Aramaic-language sources from the Christian period predominantly use the self-designation Suryāyā ("Syrian") alongside "Athoraya" and "Asoraya"[12][13] The term Suryāyā, sometimes alternatively translated as "Syrian" or "Syriac", is believed to derive from the ancient Akkadian Assūrāyu, meaning Assyrian.[14][15] The academic consensus is that the modern name "Syria" originated as a shortened form of "Assyria".[16]

Assyrian nationalism centered on a desire for self-determination developed near the end of the 19th century, coinciding with increasing contacts with Europeans, increasing levels of ethnic and religious persecution, along with increased expressions nationalism in other Middle Eastern groups, such as the Armenians, Arabs, Kurds, Jews and Turks.[17] Through the large-scale promotion of long extant terms and promotion of identities such as ʾĀthorāyā and ʾAsurāyā, Assyrian intellectuals and authors hoped to inspire the unification of the Assyrian nation, transcending long-standing religious denominational divisions.[17] This effort has been met with both support and some opposition in various religious communities; some denominations have rejected unity and promoted alternate religious identities, such as "Aramean", "Syriac" and "Chaldean". Though some religious officials and activists have promoted such identities as separate ethnic groups rather than simply religious groups, they are not generally treated as such by international organizations or historians, and historically, genetically, geographically and linguistically these are all the same people.[18]

Assyrians after the Assyrian Empire

Early assumption of Assyrian annihilation

Ancient Assyria fell in the late 7th century BC through the Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire, with its major population centers violently sacked and most of its territory incorporated into the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[19] In the millennia following the fall of Assyria, knowledge of the ancient empire chiefly survived in western literary tradition through accounts of Assyria in the Hebrew Bible and works by classical authors,[20] both of which described Assyria's fall as violent and comprehensive destruction.[21][22] Before the 19th century, the prevalent belief in Biblically influenced western scholarship was that ancient Assyria and Babylonia had been literally annihilated due to provoking divine wrath.[23] This belief was reinforced through archaeologists in the Middle East initially not finding many remains fitting with the conventional European image of ancient cities, with stone columns and great sculptures, beyond those of ancient Persia;[23] Assyria and other Mesopotamian civilizations left no magnificent ruins above ground—all that remained to see were huge grass-covered mounds in the plains which travellers at times believed to simply be natural features of the landscape.[20] Early European archaeologists in the Middle East were also for the most part more interested in confirming Biblical truth through their excavations than to spend time on new interpretations of the evidence they discovered.[24]

Though the Bible and other Hebrew texts describe the destruction of the Assyrian Empire, they do not actually claim that the Assyrian people were destroyed. The 2nd century BC apocryphal Book of Judith states that the Neo-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC) "ruled over the Assyrians in the great city of Nineveh", the Book of Ezra refers to the Persian king Darius I as "king of Assyria", and the Book of Isaiah states that there will come a day when God will proclaim "Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel my heritage".[25] The idea of Assyrian annihilation, despite increasing evidence to the contrary, proved to be enduring in western academia. As late as 1925, the Assyriologist Sidney Smith wrote that "The disappearance of the Assyrian people will always remain a unique and striking phenomenon in ancient history. Other, similar kingdoms and empires have indeed passed away, but the people have lived on ... No other land seems to have been sacked and pillaged so completely as was Assyria".[26] Just a year later, Smith had abandoned the idea of the Assyrians having been eradicated and recognized the persistence of Assyrians through the Christian period.[27]

Post-imperial Assyria in modern Assyriology

Modern Assyriology does not support the idea that the fall of Assyria also brought with it a complete eradication of the Assyrian people and their culture.[29] Though in the past regarded as a "post-Assyrian" age, Assyriologists today consider the last period of ancient Assyrian history to be the long post-imperial period,[29][30] extending from 609 BC to around AD 240, and support a continuity into the present day.[29] Though the centuries that followed the fall of Assyria are characterized by a distinct lack of surviving sources from the region in comparison to previous eras,[29] the idea that Assyria was rendered uninhabited and desolated stems from the contrast with the richly attested Neo-Assyrian period, not necessarily from the actual sources from the post-imperial period.[31]

Though the Assyrian bureaucracy and governmental institutions disappeared with Assyria's fall, Assyrian population centers and culture did not.[31] At Dur-Katlimmu, one of the largest settlements along the Khabur river, a large Assyrian palace, dubbed the "Red House" by archaeologists, continued to be used in Neo-Babylonian times, with cuneiform records there being written by people with Assyrian names, in Assyrian style, though dated to the reigns of the early Neo-Babylonian kings.[32] These documents mention officials with Assyrian titles and invoke the ancient Assyrian national deity Ashur.[31] Two Neo-Babylonian texts discovered at the city of Sippar in Babylonia attest to there being royally appointed governors at both Assur and Guzana, another Assyrian site in the north. Arbela is attested as a thriving city, but only very late in the Neo-Babylonian period, and there were attempts to revive the city of Arrapha in reign of Neriglissar (r. 560–556 BC), who returned a cult statue to the site. Harran was revitalized, with its great temple dedicated to the lunar god Sîn being rebuilt under Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC).[32]

Individuals with Assyrian names are attested at multiple sites in Assyria and Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian Empire, including Babylon, Nippur, Uruk, Sippar, Dilbat and Borsippa. The Assyrians in Uruk apparently continued to exist as a community until the reign of the Achaemenid king Cambyses II (r. 530–522 BC) and were closely linked to a local cult dedicated to Ashur.[33] Many individuals with clearly Assyrian names are also known from the rule of the Achaemenid Empire, sometimes in high levels of government. A prominent example is Pan-Ashur-lumur, who served as the secretary of Cambyses II.[34] The temple dedicated to Ashur in Assur was rebuilt by local Assyrians in the reign of Cyrus the Great.[35]

Under the Seleucid and Parthian empires, efforts were made to revitalize Assyria and the ancient great cities began to be resettled,[36] with the predominant portion of the population remaining native Assyrian.[37] The original Assyrian capital of Assur is in particular known to have flourished under Parthian rule.[38] Continuity from ancient Assyria is clear in Assur during this period, with personal names of the city's denizens greatly reflecting names used in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, such as Qib-Assor ("command of Ashur"), Assor-tares ("Ashur judges") and even Assor-heden ("Ashur has given a brother", a late version of the name Aššur-aḫu-iddina, i.e. Esarhaddon).[39] The Assyrians at Assur continued to follow the traditional ancient Mesopotamian religion, worshipping Ashur (at this time known as Assor) and other gods.[40] Assur may even have been the capital of its own semi-autonomous vassal state, either under the suzerainty of the Kingdom of Hatra,[41] or under direct Parthian suzerainty.[42] Though this golden age of Assur came to an end with the conquest, sack and destruction of the city by the Sasanian Empire c. AD 240,[43] the inscriptions, temples, continued celebration of festivals and the wealth of theophoric elements (divine names) in personal names of the Parthian period illustrate a strong continuity of traditions, and that the most important deities of old Assyria were still worshipped at Assur more than 800 years after the Assyrian Empire had been destroyed.[8]

Identity in ancient Assyria

Development and distinctions

Ethnicity and culture are largely based in self-perception and self-designation.[2] In ancient Assyria, a distinct Assyrian identity appears to have formed already in the Old Assyrian period (c. 2025–1364 BC), when distinctly Assyrian burial practices, foods and dress codes are attested[44] and Assyrian documents appear to consider the inhabitants of Assur to be a distinct cultural group.[45] A wider Assyrian identity appears to have spread across northern Mesopotamia under the Middle Assyrian Empire (c. 1363–912 BC), since later writings concerning the reconquests of the early Neo-Assyrian kings refer to some of their wars as liberating the Assyrian people of the cities they reconquered.[46] Though there for much of ancient Assyria's history existed a distinct Assyrian identity, Assyrian culture and civilization, like any other culture and civilization, did not develop in isolation. As the Assyrian Empire expanded and contracted, elements from regions the Assyrians conquered or traded with culturally influenced the Assyrian heartland and the Assyrians themselves. Early Assyrian culture was greatly influenced by the Hurrians, a people that also lived in northern Mesopotamia, and by the culture of southern Mesopotamia, particularly that of Babylonia.[3]

Surviving evidence suggests that the ancient Assyrians had a relatively open definition of what it meant to be Assyrian. Modern ideas such as a person's ethnic background, or the Roman idea of legal citizenship, do not appear to have been reflected in ancient Assyria.[2] Although Assyrian accounts and artwork of warfare frequently describe and depict foreign enemies, they are not depicted with different physical features, but rather with different clothing and equipment. Assyrian accounts describe enemies as barbaric only in terms of their behavior, as lacking correct religious practices, and as doing wrongdoings against Assyria. All things considered, there does not appear to have been any well-developed concepts of ethnicity or race in ancient Assyria.[47] What mattered for a person to be seen by others as Assyrian was mainly fulfillment of obligations (such as military service), being affiliated with the Assyrian Empire politically, and maintaining loyalty to the Assyrian king; some kings, such as Sargon II (r. 722–705 BC), explicitly encouraged assimilation and mixture of foreign cultures with that of Assyria.[2]

Pre-modern self-identities

Though many foreign states ruled over the Assyrian heartland in the millennia following the empire's fall, there is no evidence of any large scale influx of immigrants that replaced the original population,[2] which instead continued to make up a significant portion of the region's people until Mongol and Timurid massacres in the late 14th century.[48] In pre-modern ecclesiastical Syriac-language (the type of Aramaic used in Christian Mesopotamian writings) sources, the typical self-designations used is suryāyā (as well as the shortened surayā), and sometimes ʾāthorāyā ("Assyrian") and ʾārāmāyā ("Aramaic" or "Aramean").[12][49] A reluctance of the overall Christian population to adopt ʾĀthorāyā as a self-designation probably derives from Assyria's portrayal in the Bible. "Assyrian" (Āthorāyā) also continuously survived as the designation for a Christian from Mosul (ancient Nineveh) and Mesopotamia in general.[50] It is clear from the surviving sources that ʾārāmāyā and suryāyā were not distinct and mutually exclusive identities, but rather interchangeable terms used to refer to the same people; the Syriac author Bardaisan (154–222) is for instance referred to in 4th-century Syriac translations of Eusebius's Church History as both ārāmāyā and suryāyā.[12]

Suryāyā, which also occurs in the forms suryāyē and sūrōyē,[14] though sometimes translated to "Syrian",[51] is believed to derive from the ancient Akkadian term assūrāyu ("Assyrian"), which was sometimes even in ancient times rendered in the shorter form sūrāyu.[14][15] Luwian and Aramaic texts from the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, such as the Çineköy inscription, sometimes use the shortened "Syria" for the Assyrian Empire.[52] The consensus in modern academia is thus that "Syria" is simply a shortened form of "Assyria".[16] The modern distinction between "Assyrian" and "Syrian" is the result of ancient Greek historians and cartographers, who designated the Levant as "Syria" and Mesopotamia as "Assyria". By the time the terms are first attested in Greek texts (in the 4th century BC), the local denizens in both the Levant and Mesopotamia had already long used both terms interchangeably for the entire region, and continued to do so well into the later Christian period.[53] Whether the Greeks began referring to Mesopotamia as "Assyria" because they equated the region with the Assyrian Empire, long fallen by the time the term is first attested in Greek, or because they named the region after the people who lived there, the (As)syrians, is not known.[54]

Although suryāyā is thus clearly connected to "Assyrian", the more prevalent term for ancient Assyrians, ʾāthorāyā is not the typical self-designation in pre-modern sources. Syriac sources did however prominently use ʾāthorāyā in other contexts, particularly in relation to ancient Assyria. Ancient Assyria was typically referred to as ʾāthor, which also survived as a designation for the region surrounding its last great capital, Nineveh.[55] The reluctance of Medieval Syriac Christians to use ʾāthorāyā as a self-designation could perhaps be explained by the Assyrians described in the Bible being prominent enemies of Israel; the term ʾāthorāyā was sometimes employed in Syriac writings as a term for enemies of Christians. In this context, the term was sometimes applied to the Persians of the Sasanian Empire; the 4th-century Syriac writer Ephrem the Syrian for instance referred to the Sasanian Empire as "filthy ʾāthor, mother of corruption". In a similar fashion, the term in this context was also sometimes applied to the later Muslim rulers.[55] Though not used by the overall Syriac-speaking community in the Middle Ages, the term ʾāthorāyā did survive as a self-identity throughout the period as it was the typically used designation for a Syriac Christian from Mosul (ancient Nineveh) and its vicinity.[55]

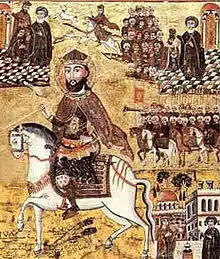

Pre-modern Syriac-language sources at times identified positively with the ancient Assyrians[56] and drew connections between the ancient empire and themselves.[51] Most prominently, ancient Assyrian kings and figures long appeared in local folklore and literary tradition[57] and claims of descent from ancient Assyrian royalty were forwarded both for figures in folklore and by actual living high-ranking members of society in northern Mesopotamia.[58] Figures like Sargon II,[59] Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BC), Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC), Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin long figured in local folklore and literary tradition.[57] In large part, tales from the Sasanian period and later times were invented narratives, based on ancient Assyrian history but applied to local and current landscapes.[60] Medieval tales written in Syriac, such as that of Behnam, Sarah, and the Forty Martyrs, for instance by and large characterize Sennacherib as an archetypical pagan king assassinated as part of a family feud, whose children convert to Christianity.[57]

The 7th-century Assyrian History of Mar Qardagh made the titular saint, Mar Qardagh, out to be a descendant of the legendary Biblical Mesopotamian king Nimrod and the historical Sennacherib, with his illustrious descent manifesting in Mar Qardagh's mastery of archery, hunting and polo.[61] A sanctuary constructed for Mar Qardagh during this time was built directly on top of the ruins of a Neo-Assyrian temple.[62] The legendary figure Nimrod, otherwise traditionally viewed as simply Mesopotamian, is explicitly referred to as Assyrian in many of the Sasanian-period texts and is inserted into the line of Assyrian kings.[59] Nimrod, as well as other legendary Mesopotamian (though explicitly Assyrian in the texts) rulers, such as Belus and Ninus, sometimes play significant roles in the writings.[63] Certain Christian texts considered the Biblical figure Balaam to have prophesied the Star of Bethlehem; a local Assyrian version of this narrative appears in some Syriac-language writings from the Sasanian period, which allege that Balaam's prophecy was remembered only through being transmitted through the ancient Assyrian kings.[64] In some stories, explicit claims of descent are made. According to the 6th-century History of Karka, twelve of the noble families of Karka (ancient Arrapha) were descendants of ancient Assyrian nobility who lived in the city during the time of Sargon II.[65]

Modern identity and nationalism

19th century identities and developments

Early travellers and missionaries in northern Mesopotamia in the 19th century observed connections between the indigenous Christian population and the ancient Assyrians. The British traveller Claudius Rich (1787–1821) referenced "Assyrian Christians" in Narrative of a Residence in Koordistan and on the site of Ancient Nineveh (published posthumously in 1836, though describing an 1820 journey). It is just possible that Rich considered "Assyrian" a geographic, rather than ethnic, term since he in a footnote on the same page also referenced the "Christians of Assyria". More clear-cut evidence of Assyrian self-identity in the 19th century can be seen in the writings of the American missionary Horatio Southgate (1812–1894). In Southgate's Narrative of a Visit to the Syrian [Jacobite] Church of Mesopotamia (1844) he remarked with surprise that Armenians referred to the Syriac Christians as Assouri, which Southgate associated with the English "Assyrians", rather than Syriani, which he himself had been using.[66] Armenian and Georgian sources have since antiquity consistently referred to Assyrians as Assouri or Asori.[67][66] Southgate also mentioned that the Syriac Christians themselves at this point claimed origin from the ancient Assyrians as "sons of Assour". Southgate's account thus demonstrates that modern Assyrians still claimed ancient Assyrian descent already in the early 19th century.[66]

Connections between the modern population and ancient Assyrians were further popularized in the west and academia by the British archaeologist and traveller Austen Henry Layard (1817–1894), responsible for the early excavations of several major ancient Assyrian sites, such as Nimrud. In Nineveh and its Remains (1849), Layard argued that the Christians he met in northern Mesopotamia were "descendants of the ancient Assyrians". It is possible that Layard's knowledge of them as such derived from his partnership with the local Assyrian archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam (1826–1910).[66]

Towards the end of the 19th century, a so-called "religious renaissance" or "awakening" took place in Urmia, Iran. Perhaps partly encouraged by Anglican, Roman Catholic and Russian Orthodox missionary efforts, the concepts of nation and nationalism were introduced to the Assyrians in Urmia, who began to adopt the term ʾāthorāyā as a self-identity, and began building a national ideology more heavily based around ancient Assyria tgan Christianity. This was not an isolated phenomenon: Middle Eastern nationalism, probably influenced by developments in Europe, also began to be strongly expressed in other communities during this time, such as among the Armenians, Arabs, Kurds and Turks. This time also saw the development of Literary Urmia Aramaic, a new literary language based on the at the time spoken Neo-Aramaic dialects. Through the promotion of an identity rooted in ancient Assyria, various communities could transcend their denominational differences and unite under one national identity.[17]

Contemporary identities and name debate

In the years before World War I, several prominent Aramaic-language authors and intellectuals promoted Assyrian nationalism. Among them were Freydun Atturaya (1891–1926), who in 1911 published an influential article titled Who are the Syrians [surayē]? How is Our Nation to Be Raised Up?, in which he pointed out the connection between surayē and "Assyrian" and argued for the adoption of ʾāthorāyā. The early 20th century saw an increase in the use of the term ʾāthorāyā as a self-identity. Also used as the neologism ʾasurāyā, perhaps inspired by the Armenian Asori.[17] The adoption of ʾāthorāyā and a stronger association with ancient Assyria through nationalism is not a unique development in regard to the Assyrians. Greeks, for instance, due to associating the term "Hellene" with the pagan religion, overwhelmingly self-identified as Romans (Rhōmioi)[68] up until nationalism around the time of the Greek War of Independence, when a more strong association with Ancient Greece spread among the populace.[69][70] Today, sūryōyō or sūrāyā are the predominant self-designations used by Assyrians in their native language, though they are typically translated as "Assyrian" rather than "Syrian".[71]

Today, as a consequence of World War I, the Sayfo (Assyrian genocide) and various other massacres, a majority of the Assyrians have been displaced from their homeland, and today they live in diaspora communities in countries such as Germany, Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Greece, Australia, New Zealand and the United States. In the aftermath of these events, explicit Assyrian self-identity became even more widespread and established in their communities, not only in order to unify communities in the diaspora (which often originated in different regions) but also because "Syrian" became internationally established as the demonym of the newly created country of Syria.[72] Some Assyrians who were not members of the Church of the East also embraced Assyrian nationalism, such as D. B. Perley (1901–1979), who in 1933 helped found the Assyrian National Federation and religiously identified himself as a Syriac Orthodox Christian but ethnically identified himself as an Assyrian. In 1935, Perley wrote that "The Assyrians, although representing but one single nation as the direct heirs of the ancient Assyrian Empire … are now doctrinally divided … No one can coherently understand the Assyrians as a whole until he can distinguish that which is religion or church from that which is nation …" and even proposed uniting all Assyrians under a single patriarch of the Church of the East.[1]

For communities that identify themselves as Assyrian, Assyrian continuity forms a key part of their self-identity. Many modern Assyrians are named after ancient Mesopotamian figures, such as Sargon, Sennacherib and Nebuchadnezzar, and the modern Assyrian flag displays symbolism which is derived from ancient Assyria.[1] From the second half of the 20th century to the present, Assyrians, particularly in the diaspora, have continued to promote Assyrian nationalism as a unifying force among their people. Some denominational groups have opposed being lumped in as "Assyrians" and as a result, they have founded counter-movements of their own;[1] the so-called "name debate" is still a hotly discussed topic within Syriac Christian communities today, especially in the diaspora which lives outside the Assyrian homeland.[73]

Followers of the Assyrian Church of the East have historically most often been exposed to cultural influences from Iran whereas followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church have been exposed to cultural influences from Greece.[6] In the Syriac Orthodox Church, officials have been important part of advancing secular Assyrianism, then later reducing it by creating of separate "Syrian"[lower-alpha 2] or "Arameans" identities. For instance, Patriarch Ignatius Aphrem I (then bishop, later patriarch between 1933 and 1957) was a part of the Assyrian Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, which asked for a homeland for the Assyrian people. The patriarchal residence was later moved to Syria and after the Simele massacre, Ignatius Aphrem I took an anti-Assyrian stance, which came to influence the religious mindset of the Syriac Orthodox community. The church was then called the Assyrian Apostolic Church of Antioch in the United States, a name Ignatius Aphrem I came to change to the Syrian Orthodox.[74][75] In 1981, Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I advocated Syriac identity over both Assyrian and Aramean identity.[1] More recently, many Syriac Orthodox adherents have preferred to identify themselves as "Syriac" in English (the name of their church and the liturgical language and an alternate transliteration of suryayā), some identifying as Syriac and Assyrian or Aramean interchangeably. Some members of the Chaldean Catholic Church, "Chaldeans", have also lobbied for recognition as a distinct group in recent times.[76] Modern international organizations generally do not recognize Assyrians, Syriacs, Arameans and Chaldeans as members of different ethnic groups, instead, they merely consider these names alternate names[18] and numerous church leaders have also affirmed that they belong to the same ethnic group, albeit to different Christian denominations.[77]

Other forms of continuity

In addition to continuity in self-designation and self-perception, there continued to be important continuities between ancient and contemporary Mesopotamia in terms of religion, literary culture and settlement well after the post-imperial period.[62]

Assyrian settlements

Assyrian settlements continued to be occupied into the Christian period. The ancient capital of Nineveh, for instance, became the seat of a bishop, the Bishop of Nineveh, and a church (later converted to a mosque under Islamic rule) was built on top of the ruins of an ancient Assyrian palace. The main population center in the city gradually shifted to the opposite bank of the river, which became the city today known as Mosul; ancient Nineveh only gradually fell into ruin and eventually became open countryside.[23] Though most of the old population centers were similarly gradually abandoned and fell into ruin some also endured. The ancient city of Arbela, today known as Erbil, has been continuously inhabited since the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[78]

Religion

Although the ancient Mesopotamian pantheon ceased to be worshipped at Assur with the city's destruction in the 3rd century AD, it persisted at other localities, despite the overwhelming conversion of the region to Christianity, for much longer; the old faith persisted at Harran until at least the 10th century and at Mardin until as late as the 18th century.[79]

The Fast of Nineveh is a three-day fast found in all of the traditional churches of modern Assyrians, such as the Syriac Orthodox Church, Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church.

Language

In the wake of the Late Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BC, Aramean tribes began to migrate into Assyrian territory. In the first millennium BC, Aramean influence on Assyria grew greater and greater, owing to further migrations as well as mass deportations enacted by several Assyrian kings.[3] Though the expansion of the Assyrian Empire, in combination with resettlements and deportations, changed the ethno-cultural make-up of the Assyrian heartland, there is no evidence to suggest that the more ancient Assyrian inhabitants of the land ever disappeared or became restricted to a small elite, nor that the ethnic and cultural identity of the new settlers was anything other than "Assyrian" after one or two generations.[2]

Because the Assyrians never imposed their language on foreign peoples whose lands they conquered outside of the Assyrian heartland, there were no mechanisms in place to stop the spread of languages other than Akkadian. Beginning with the migrations of Aramaic-speaking settlers into Assyrian territory during the Middle Assyrian period, this lack of linguistic policies facilitated the spread of the Aramaic language.[80] As the most widely spoken and mutually understandable of the Semitic languages (the language group containing many of the languages spoken through the empire),[81] Aramaic grew in importance throughout the Neo-Assyrian period and increasingly replaced the Akkadian language even within the Assyrian heartland itself.[82][9] From the 9th century BC onwards, Aramaic became the de facto lingua franca, with Akkadian becoming relegated to a language of the political elite (i.e. governors and officials).[80]

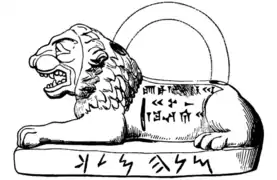

The widespread adoption of the language does not indicate a wholesale replacement of the original native population; the Aramaic language was used not only by settlers but also by native Assyrians, who adopted it and its alphabetic script.[3] The Aramaic language had entered the Assyrian royal administration by the reign of Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BC), given that Aramaic writings are known from a palace he built in Nimrud.[9] By the time of Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 745–727 BC), the Assyrian kings employed both Akkadian and Aramaic-language royal scribes, confirming the rise of Aramaic to a position of an official language used by the imperial administration.[9][10] It is clear that Aramaic was spoken by the Assyrian royal family from at least the late 8th century BC onwards, given that Tiglath-Pileser's son Shalmaneser V (r. 727–722 BC) owned a set of lion weights inscribed with text in both Akkadian and Aramaic.[10] A recorded drop in the number of cuneiform documents late in the reign of Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BC) could indicate a greater shift to Aramaic, often written on perishable materials like leather scrolls or papyrus,[80] though it could perhaps alternatively be attributed to political instability in the empire.[83] The denizens of Assur and other former Assyrian population centers under Parthian rule, who clearly connected themselves to ancient Assyria, wrote and spoke Aramaic.[37]

Though modern Assyrian languages, most prominently the Suret language, are Neo-Aramaic languages with little resemblance to the old Akkadian language,[84] they are not wholly without Akkadian influence. Most notably there are numerous examples of Akkadian loanwords in both ancient and modern Aramaic languages.[85] This connection was noted already in 1974, when a study by Stephen A. Kaufman found that the Syriac language, an Aramaic dialect today mainly used liturgical language, has at least fourteen exclusive (i.e. not attested in other dialects) loanwords from Akkadian, including nine of which are clearly from the ancient Assyrian dialect (six of which are architectural or topographical terms).[86] A 2011 study by Kathleen Abraham and Michael Sokoloff on 282 words previously believed to have been Aramaic loanwords in Akkadian determined that many such cases were questionable, and also found that 15 of those words were actually Akkadian loanwords in Aramaic and that the direction of the loan could not be determined in 22 cases; Abraham's and Sokoloff's conclusion was that the number of loanwords from Akkadian to Aramaic was far larger than the number of loanwords from Aramaic to Akkadian.[87]

Academia and politics

The use of the Assyrian name by modern Assyrians has historically led to controversy and misunderstanding, not only within but also outside the Assyrian community.[73] Discussions on the connection between the modern and ancient Assyrians have also entered into academia.[73] In addition to support by prominent historical Assyriologists, such as Austen Henry Layard[66] and Sidney Smith,[27] Assyrian continuity enjoys wide support within contemporary Assyriology. Among proponents of continuity are prominent Assyriologists such as Simo Parpola,[73][88] Robert D. Biggs,[89] H. W. F. Saggs,[90] Georges Roux,[91] J. A. Brinkman[92] and Mirko Novák.[2] Historians of other fields have also supported Assyrian continuity, such as Richard Nelson Frye,[93] Philip K. Hitti,[94] Patricia Crone,[95] Michael Cook,[95] Mordechai Nisan,[96] Aryo Makko[97] and Joshua J. Mark (contributor of the World History Encyclopedia).[98] Other scholars supporting continuity include, among others, the linguist Judah Segal,[99] the political scientist James Jupp,[100] the genocide researcher Hannibal Travis,[101][102] and the geneticists Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza,[103] Mohammad Taghi Akbari, Sunder S. Papiha, Derek Frank Roberts and Dariush Farhud.[104] Numerous scholars who themselves are of Assyrian origin, such as Efrem Yildiz,[105] Sargon Donabed[106] and Odisho Malko Gewargis,[107] have also published academic works in support of Assyrian continuity.[105][106][107]

Some academics, most notably the historians J.F. Coakley,[73] John Joseph, David Wilmshurst and Adam H. Becker, have opposed continuity between modern and ancient Assyrians, typically arguing that modern Assyrian identity only emerged in the middle to late 19th century as a consequence of interactions with foreign missionaries and/or the discovery of ancient Assyrian ruins.[108][109] Wholesale opposition of Assyrian continuity is not reflected within Assyriology. Karen Radner considers Assyrian continuity to still be a matter of debate, but also opposes the idea that Assyrian identity only emerged in the 19th century, noting that modern Christians in northern Mesopotamia saw themselves as descendants of the ancient Assyrians long before the discovery of ancient sites and visits by foreign missionaries,[43] as can for instance be gathered from the accounts of Horatio Postgate.[66] Some opponents to Assyrian continuity, such as Becker, have argued that the rich Christian literature from the Sasanian period connecting with ancient Assyria was simply based on the Bible, rather than actual remembrance of ancient Assyria,[62] despite several figures appearing in the tales, such as Esarhaddon and Sargon II, barely being mentioned in the Bible.[lower-alpha 3] The texts are also very much a local Assyrian phenomenon, given that the historical accounts presented in them are at odds with those of other historical writings of the Sasanian Empire.[111]

Names clearly reminiscent of those used by Assyrians in the Neo-Assyrian Empire continued to be used at Assur throughout the post-imperial period, at least until the 3rd century AD.[39] Some opponents to Assyrian continuity, such as David Wilmshurst, hold that ancient Assyrian names ceased being used in the Christian period and that this in turn was evidence of a lack of continuity.[112] There is some evidence of continued use of names with explicit ancient Mesopotamian connections in the Christian period; Arabic-language records from 13th-century Rumkale for instance record a man by the name Nebuchadnezzar (rendered Bukthanaṣar in the Arabic text), a relative of a Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church named Philoxenus Nemrud (also a name with ancient Assyrian connections, deriving either from Nimrud or Nimrod); both of these names are also however mentioned in the Bible.[113] Modern Assyrian authors, such as Odisho Malko Gewargis, contend that a decrease in ancient pagan names invoking gods such as Ashur, Nabu and Sîn is hardly surprising given the Christianization of the Assyrians; similar cases of native names being increasingly replaced by Biblically derived names are also known from numerous other Christianized peoples.[107]

Modern Assyrians consider opposition to Assyrian continuity to be offensive and associate it with other historical forms of oppression against them. Sargon Donabed, for instance, considers the use of terms such as "Chaldeans", "Syrian", "Syriacs", "Arameans", or more extremely "Arab Christians", "Kurdish Christians" and "Turkish Christians", to be harmful as they add to division and confusion in regard to identity and are "clearly reflective of modern political parlance".[114] These views are partly attributable to the actions of the government in Ba'athist Iraq (1968–2003), which sought to counteract Assyrian demands for autonomy through refusing to recognize Assyrians as a third ethnic minority of the country, instead promoting Assyrians, "Syrians" and Chaldeans as separate peoples, and undercounted Assyrians in censuses; in 1977, it was made impossible to register as Assyrian in the national census and Assyrians were consequently forced to register as Arabs for fear of losing employment and ration cards.[115]

Genetic testing of Assyrian populations is a relatively new field of study, but has hitherto supported continuity from Bronze and Iron Age populations and underlined the notion that Assyrians historically rarely intermarried with surrounding populations.[116] Genetic studies conducted in 2000 and 2008 support Assyrians as genetically distinct from other groups in the Middle East, with high endogamy; this indicates that the community has historically been relatively closed owing to their religious and cultural traditions, with little intermixture with other groups.[117]

See also

Notes

- At the height of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, there were around 20 million Assyrians.[6] Settlers came from Babylonia, the Levant, among other places.[7]

- Later "Syriac", see below

- Sargon II was for instance due to being mentioned only once in the Bible long forgotten in western scholarship and was only accepted as a real Assyrian king within Assyriology in the 1860s.[110]

References

- Butts 2017, p. 605.

- Novák 2016, p. 132.

- Frahm 2017, p. 7.

- Biggs 2005, p. 10.

- Saggs 1984, p. 290.

- Parpola 2004, p. 22.

- Valk 2020, p. 77-103.

- Hauser 2017, p. 240.

- Radner 2021, p. 149.

- Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 319.

- Parpola 2004, p. 15.

- Butts 2017, p. 600.

- Makko 2012, p. 298.

- Benjamen 2022, p. 2.

- Parpola 2004, pp. 16–17.

- Shehadeh 2011, p. 17.

- Butts 2017, p. 603.

- Petrosian 2006, pp. 143–144.

- Frahm 2017b, p. 192.

- Trolle Larsen 2017, pp. 583–584.

- Frahm 2017c, p. 560.

- Kuhrt 1995, p. 239.

- Reade 2018, p. 286.

- Dalley 1993, p. 134.

- Frahm 2017c, pp. 560–561.

- Dalley 1993, pp. 135–136.

- Smith 1926, p. 69.

- Radner 2015, p. 20.

- Hauser 2017, p. 229.

- Frahm 2017, p. 5.

- Kuhrt 1995, p. 240.

- Hauser 2017, p. 230.

- Frahm 2017b, p. 194.

- Parpola 1999.

- Radner 2015, p. 6.

- Hauser 2017, p. 238.

- Reade 1998, p. 71.

- Haider 2008, p. 193.

- Livingstone 2009, p. 154.

- Haider 2008, p. 197.

- Radner 2015, p. 19.

- Harper et al. 1995, p. 18.

- Radner 2015, p. 7.

- Düring 2020, p. 39.

- Michel 2017, p. 81.

- Düring 2020, p. 145.

- Bahrani 2006, pp. 56–57.

- Filoni 2017, p. 37.

- Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 81.

- Butts 2017, p. 600-601.

- Butts 2017, p. 601.

- Rollinger 2006, pp. 285–287.

- Tamari 2019, p. 113.

- Rollinger 2006, p. 284.

- Butts 2017, pp. 600–601.

- Hauser 2017, p. 241.

- Kalimi & Richardson 2014, p. 5.

- Payne 2012, pp. 205, 217.

- Payne 2012, p. 214.

- Payne 2012, p. 209.

- Payne 2012, p. 205.

- Payne 2012, p. 208.

- Minov 2020, pp. 187, 191.

- Minov 2020, p. 203.

- Payne 2012, p. 217.

- Butts 2017, p. 602.

- Becker 2015, p. 328.

- Cameron 2009, p. 7.

- Efstathiadou 2011, p. 191.

- Morrison 2018, p. 39.

- Parpola 2004, p. 11.

- Butts 2017, p. 604.

- Butts 2017, p. 599.

- Lundgren 2023, p. 5.

- Donabed & Mako 2009, p. 80-81.

- Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. ix.

- Salem 2020.

- Trolle Larsen 2017, p. 584.

- Parpola 2004, p. 21.

- Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 318.

- Radner 2021, p. 147.

- Frahm 2017b, p. 180.

- Frahm 2017b, p. 190.

- Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 314.

- Abraham & Sokoloff 2011, pp. 22, 59.

- Kaufman 1974, p. 164.

- Abraham & Sokoloff 2011, p. 59.

- Parpola 2004, p. 5–22.

- Biggs 2005, p. 10: "Especially in view of the very early establishment of Christianity in Assyria and its continuity to the present and the continuity of the population, I think there is every likelihood that ancient Assyrians are among the ancestors of modern Assyrians of the area".

- Saggs 1984, p. 290: "The destruction of the Assyrian Empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carried on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and after various vicissitudes, these people became Christians. These Christians, and the Jewish communities scattered amongst them, not only kept alive the memory of their Assyrian predecessors but also combined them with traditions from the Bible".

- Roux 1992, pp. 276–277, 419–420.

- Assyrian Academic Society: Summary of the Lecture "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria since there is no evidence that the population of Assyria was removed".

- Frye 1999, pp. 69–70.

- Hitti 1951, p. 519.

- Crone & Cook 1977, p. 55.

- Nisan 2002, p. 181.

- Makko 2012, p. 297-317.

- Mark 2018, "there are still Assyrians living in the regions of Iran and northern Iraq, and elsewhere, in the present day".

- Segal 1970, pp. 47, 51, 68–70.

- Jupp 2001, p. 174: "The Assyrians are the descendants of the once mighty Assyrian nation which inhabited the northern part of the country known as Iraq", "The Assyrians, who were Christians, managed to survive in the lands of their forefathers until the outbreak of the First World War".

- Travis 2010, pp. 148–151.

- Cavalli-Sforza et al. 1994, p. 218: "They are Christian and are possibly bona fide descendants of their ancient namesakes".

- Akbari et al. 1986, p. 85: "The Assyrians are a group of Christians, also known as Nestorians, with a long history in the Middle East. From historical and archaeological evidence, it is thought that their ancestors formed part of the Mesopotamian civilization".

- Yildiz 1999, p. 16-19.

- Donabed 2019, p. 118.

- Gewargis 2002, p. 89.

- Wilmshurst 2011, pp. 413–416.

- Becker 2008, p. 396.

- Holloway 2003, p. 71.

- Payne 2012, p. 215.

- Wilmshurst 2011, p. 415.

- Jackson 2020, Chapter 1.

- Donabed 2012, p. 412.

- Naby 2006, pp. 527–528.

- Travis 2010, p. 149.

- Banoei et al. 2008, p. 79.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Kathleen; Sokoloff, Michael (2011). "Aramaic Loanwords in Akkadian – A Reassessment of the Proposals". Archiv für Orientforschung. 52: 22–76. JSTOR 24595102.

- Akbari, Mohammad Taghi; Papiha, Sunder S.; Roberts, Derek Frank; Farhud, Dariush (1986). "Genetic differentiation among Iranian Christian communities". American Journal of Human Genetics. 38 (1): 84–98. PMC 1684716. PMID 3456196.

- Bahrani, Zainab (2006). "Race and Ethnicity in Mesopotamian Antiquity". World Archaeology. 38 (1): 48–59. doi:10.1080/00438240500509843. JSTOR 40023594. S2CID 144093611.

- Banoei, Mohammad Mehdi; Chaleshtori, Morteza Hashemzadeh; Sanati, Mohammad Hossein; Shariati, Parvin; Houshmand, Massoud; Majidizadeh, Tayebeh; Soltani, Niloofar Jahangir; Golalipour, Massoud (2008). "Variation ofDAT1 VNTR Alleles and Genotypes Among Old Ethnic Groups in Mesopotamia to the Oxus Region". Human Biology. 80 (1): 73–81. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[73:VODVAA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 41465951. PMID 18505046. S2CID 10417591.

- Becker, Adam H. (2008). "The Ancient Near East in the Late Antique Near East: Syriac Christian Appropriation of the Biblical East". Antiquity in Antiquity: Jewish and Christian Pasts in the Greco-Roman World. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 394–415. ISBN 9783161494116.

- Becker, Adam H. (2015). Revival and Awakening: American Evangelical Missionaries in Iran and the Origins of Assyrian Nationalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226145280.

- Bedford, Peter R. (2009). "The Neo-Assyrian Empire". In Morris, Ian; Scheidel, Walter (eds.). The Dynamics of Ancient Empires: State Power from Assyria to Byzantium. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537158-1.

- Benjamen, Alda (2022). Assyrians in Modern Iraq: Negotiating Political and Cultural Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108838795.

- Biggs, Robert D. (2005). "My Career in Assyriology and Near Eastern Archaeology" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 19 (1): 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27.

- Butts, Aaron Michael (2017). "Assyrian Christians". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Cameron, Averil (2009). The Byzantines. Oxford: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2.

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo & Piazza, Alberto (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08750-4.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, Michael A. (1977). Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521211338.

- Deutscher, G. (2009). "Akkadian". Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- Dalley, Stephanie (1993). "Nineveh after 612 BC". Altorientalische Forschungen. 20 (1): 134–147. doi:10.1524/aofo.1993.20.1.134. S2CID 163383142.

- Donabed, Sargon (2012). "Rethinking Nationalism and an Appellative Conundrum: Historiography and Politics in Iraq". National Identities. 14 (4): 407–431. doi:10.1080/14608944.2012.733208. S2CID 145265726.

- Donabed, Sargon (2019). "Persistent Perseverance: A Trajectory of Assyrian History in the Modern Age". In Rowe, Paul S. (ed.). Routledge Handbook of Minorities in the Middle East. London. ISBN 978-1138649040.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Donabed, Sargon; Mako, Shamiran (2009). "Ethno-cultural and Religious Identity of Syrian Orthodox Christians". Revue d'Histoire de l'Université de Balamand: 71–113. ISSN 1608-7526.

- Düring, Bleda S. (2020). The Imperialisation of Assyria: An Archaeological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108478748.

- Efstathiadou, Anna (2011). "Representing Greekness: French and Greek Lithographs from the Greek War of Independence (1821–1827) and the Greek-Italian War (1940–1941)" (PDF). Journal of Modern Greek Studies. 29 (2): 191–218. doi:10.1353/mgs.2011.0023. S2CID 144506772.

- Filoni, Fernando (2017). The Church in Iraq. Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0813229652.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "Introduction". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "The Neo-Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE)". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "Assyria in the Hebrew Bible". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Frye, Richard N. (1999). "Reply to John Joseph" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1): 69–70. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-11.

- Gaunt, David; Atto, Naures; Barthoma, Soner O. (2017). Let Them Not Return: Sayfo – The Genocide Against the Assyrian, Syriac, and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire. New York: Berghahn. ISBN 978-1785334986.

- Gewargis, Odisho Malko (2002). "We Are Assyrians" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 16 (1): 77–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-04-21.

- Haider, Peter W. (2008). "Tradition and change in the beliefs at Assur, Nineveh and Nisibis between 300 BC and AD 300". In Kaizer, Ted (ed.). The Variety of Local Religious Life in the Near East: In the Hellenistic and Roman Periods. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004167353.

- Harper, Prudence O.; Klengel-Brandt, Evelyn; Aruz, Joan; Benzel, Kim (1995). Assyrian Origins: Discoveries at Ashur on the Tigris: Antiquities in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-743-2.

- Hauser, Stefan R. (2017). "Post-Imperial Assyria". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Holloway, Steven W. (2003). "The Quest for Sargon, Pul and Tiglath-Pileser in the Nineteenth Century". In Chavalas, Mark W.; Younger, Jr, K. Lawson (eds.). Mesopotamia and the Bible. Edinburgh: A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-252-8.

- Hitti, Philip K. (1951). History of Syria: Including Lebanon and Palestine. London: MacMillan. OCLC 5510718.

- Jackson, Cailah (2020). Islamic Manuscripts of Late Medieval Rum, 1270s-1370s: Production, Patronage and the Arts of the Book. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1474451505.

- Jupp, James (2001). Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80789-1.

- Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (2014). "Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography: An Introduction". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- Kaufman, Stephen A. (1974). The Akkadian Influences on Aramaic. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago Assyriological Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-62281-9.

- Kuhrt, Amélie (1995). "The Assyrian heartland in the Achaemenid period". Pallas. Revue d'études antiques. 43 (43): 239–254. JSTOR 43660582.

- Livingstone, Alasdair (2009). "Remembrance at Assur: The Case of the dated Aramaic memorials". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 106: 151–157.

- Lundgren, Svante (2023). "When the Assyrian Tragedy Became Seyfo: A Study of Swedish-Assyrian Politics of Memory". Genocide Studies International. 14 (2): 95–108. doi:10.3138/GSI-2022-0002. S2CID 257178308.

- Luukko, Mikko; Van Buylaere, Greta (2017). "Languages and Writing Systems in Assyria". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Makko, Aryo (2012). "Discourse, Identity and Politics: A Transnational Approach to Assyrian Identity in the Twentieth Century". The Assyrian Heritage: threads of continuity and influence. Uppsala. ISSN 1654-630X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mark, Joshua J. (2018). "Assyria". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Michel, Cécile (2017). "Economy, Society, and Daily Life in the Old Assyrian Period". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Minov, Sergey (2020). Memory and Identity in the Syriac Cave of Treasures: Rewriting the Bible in Sasanian Iran. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004445505.

- Morrison, Susannah (2018). ""A Kindred Sigh for Thee": British Responses to the Greek War for Independence". The Thetean: A Student Journal for Scholarly Historical Writing. 47 (1): 37–55.

- Naby, Eden (2006). "Assyrian Nationalism in Iraq: Survival under Religious and Ethnic Threat". In Burszta, Wojciech J.; Kamusella, Tomasz & Wojchiechowski, Sebastian (eds.). Nationalisms Across the Globe: An Overview of Nationalisms in State-Endowed and Statless Nations, Volume II: the World. Bygoszcz: School of Humanities and Journalism. ISBN 83-87653-46-2.

- Nisan, Mordechai (2002). Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression (2nd ed.). Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1375-1.

- Novák, Mirko (2016). "Assyrians and Arameans: Modes of Cohabitation and Acculuration at Guzana (Tell Halaf)". In Aruz, Joan; Seymour, Michael (eds.). Assyria to Iberia: Art and Culture in the Iron Age. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1588396068.

- Parpola, Simo (1999). "Assyrians after Assyria". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (2).

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2): 5–22.

- Payne, Richard (2012). "Avoiding Ethnicity: Uses of the Ancient Past in Late Sasanian Northern Mesopotamia". In Pohl, Walter; Gantner, Clemens; Payne, Richard (eds.). Visions of Community in the Post-Roman World: The West, Byzantium and the Islamic World, 300–1100. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1409427094.

- Petrosian, Vahram (2006). "Assyrians in Iraq". Iran and the Caucasus. 10 (1): 138. doi:10.1163/157338406777979322. S2CID 154905506.

- Radner, Karen (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198715900.

- Radner, Karen (2021). "Diglossia and the Neo-Assyrian Empire's Akkadian and Aramaic Text Production". In Jonker, Louis C.; Berlejung, Angelika & Cornelius, Izak (eds.). Multilingualism in Ancient Contexts: Perspectives from Ancient Near Eastern and Early Christian Contexts. Stellenbosch: African Sun Media. ISBN 978-1991201164.

- Reade, Julian E. (1998). "Greco-Parthian Nineveh". Iraq. 60: 65–83. doi:10.2307/4200453. JSTOR 4200453. S2CID 191474172.

- Reade, Julian Edgeworth (2018). "Nineveh Rediscovered". In Brereton, Gareth (ed.). I am Ashurbanipal, king of the World, king of Assyria. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-48039-7.

- Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The Terms "Assyria" and "Syria" Again". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 283–287. doi:10.1086/511103. JSTOR 10.1086/511103. S2CID 162760021.

- Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140125238.

- Saggs, Henry W. F. (1984). The Might That Was Assyria. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 9780312035112.

- Salem, Chris (24 December 2020). "A Name Chaldeans Forgot: Assyria". Medium. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- Segal, Judah B. (1970). Edessa: The Blessed City. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821545-5.

- Shehadeh, Lamia Rustum (2011). "The name of Syria in ancient and modern usage". In Beshara, Adel (ed.). The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, pioneers and identity. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-61504-4.

- Smith, Sidney (1926). "Notes on "The Assyrian Tree"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 4 (1): 69–76. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00102599. JSTOR 607403. S2CID 178173677.

- Tamari, Steve (2019). "The Land of Syria in the Late Seventeenth Century: ʿAbd al-Ghani al-Nabulusi and Linking City and Countryside through Study, Travel, and Worship". In Tamari, Steve (ed.). Grounded Identities: Territory and Belonging in the Medieval and Early Modern Middle East and Mediterranean. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004385337.

- Travis, Hannibal (2010). Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-1594604362.

- Trolle Larsen, Mogens (2017). "The Archaeological Exploration of Assyria". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1118325247.

- Valk, Jonathan (1 November 2020). "Crime and Punishment: Deportation in the Levant in the Age of Assyrian Hegemony". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 384: 77–103. doi:10.1086/710485. S2CID 225379553.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.

- Yildiz, Efrem (1999). "The Assyrians: A Historical and Current Reality". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 13 (1): 15–30.