Asthall

Asthall or Asthal is a village and civil parish on the River Windrush in Oxfordshire, about 6 miles (10 km) west of Witney. It includes the hamlets of Asthall Leigh, Field Assarts, Stonelands, Worsham and part of Fordwells. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 252.[2] Asthall village is just south of the River Windrush, which also forms the south-eastern part of its boundary. The remainder of the parish including all of its hamlets lie north of the river. A minor road through Fordwells forms most of the parish's northern boundary. Most of the remainder of the parish's boundary is formed by field boundaries.

| Asthall | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) St. Nicholas' parish church | |

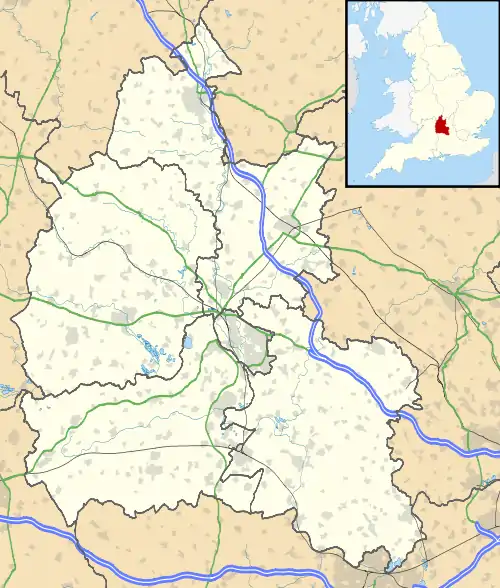

Asthall Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Population | 252 (parish) (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SP2811 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Burford |

| Postcode district | OX18 |

| Post town | Witney |

| Postcode district | OX29 |

| Dialling code | 01993 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

Name

The name Asthall derives from the Old English words ēast 'east' + healh 'corner, nook', attested in the early 11th century as East Heolon.[3]

Archaeology

On Leigh Hale Plain there are two barrows that may date from the Bronze Age.[4] The course of Akeman Street Roman Road that linked Watling Street with Fosse Way passes through the parish just south of the village and through the middle of Windrush Farm. The road crossed the Windrush about 1⁄2 mile (800 m) east of the village. Traces of a Roman settlement have been found on both sides of the course of the road on low-lying land between Windrush Farm and the site of the Roman river crossing.[5] It was occupied from the middle of the first century AD to the latter part of the fourth century.[4] Artefacts recovered include a bronze figurine of a bird seizing a hare.[6] 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) south of the village, beside the main Witney – Burford road (now part of the A40 trunk road) is an early 7th century Saxon burial mound, Asthall barrow, that contained the cremated remains of a man.[4] Objects from the barrow are now in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Wychwood Forest

The parish is elongated north-eastwards. A record of 1300 states that the manor of Asthall was extended into Wychwood Forest after 1154.[4] The name of Field Assarts in the north-east of the parish refers to assarting:[4] the medieval process of clearing any uncultivated land to convert it to agriculture.[7] The north-eastern parts of Asthall parish remained purlieus of the Wychwood until it was disafforested in 1857.[4]

Parish church

The Church of England parish church of Saint Nicholas[8] was enlarged in about 1160, when the north aisle and north transept were added to an earlier church. The north transept arch and the arcade between the nave and north aisle are in the Transitional style between Norman architecture and Early English Gothic.[9] The chancel was rebuilt in the 13th century in the Early English Gothic style. The west window of the north aisle is in the early Decorated Gothic style of the late 13th century. There is another Decorated Gothic window on the south side of the nave. In about 1350 the north transept was remodelled and its roof height increased above that of the nave. After this the remaining windows were added in the Perpendicular Gothic style. The west tower was built in the 15th century.[10]

The church was restored in 1885, and the chancel arch was probably rebuilt at this time.[9] The church is a Grade II* listed building.[11] The tower has a ring of six bells. The Wokingham foundry cast the fifth and tenor bells in about 1499.[12] John Taylor & Co cast the fourth bell in 1859, presumably at the foundry they then had in Oxford.[13] Whitechapel Bell Foundry cast the treble, second and third bells in 2005.[12] St Nicholas' also has a Sanctus bell, which was cast in 1640 by James Keene,[12] who had foundries at Woodstock and Bedford.[13] St Nicholas' parish is now a member of the Benefice of Burford, Fulbrook, Taynton, Asthall, Swinbrook and Widford.[14]

Asthall Hoard

In the summer of 2007 a hoard of 110 gold angel and half-angel coins was found during building work at Asthall.[15] The coins were minted at dates from 1470 to 1526, most of them in the brief second reign of Henry VI (1470–71) or the reign of Richard III (1483–85).[15] The hoard is believed to have been buried in the latter half of the reign of Henry VIII (1509–47).[15] In April 2010 a coroner found the hoard to be treasure as defined by the Treasure Act 1996, and in August the Treasure Valuation Committee valued it at £280,000.[15] The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford acquired the hoard in December 2010, and put the coins on display from March 2011.[15]

Asthall Manor House

Asthall Manor House is an H-shaped house built in about 1620 for Sir William Jones. In 1810 the 1st Baron Redesdale (of the first creation) bought the house, which then remained in his family until 1926. In 1916 the architect Charles Bateman altered and enlarged the house for the 2nd Baron Redesdale (of the second creation).[10] Lord Redesdale's daughters were the six Mitford sisters, of whom Deborah, the youngest, was born at Asthall Manor in 1920. In 1926 the Mitford family left Asthall and moved to a new country house that Lord Redesdale had had built at Swinbrook.

Asthall Barony

The Tenant-in-Chief of Asthall in the Domesday Book in 1086 was Roger d'Ivery. Another name for a tenant-in-chief was a baron, specifically one who held tenure per baroniam.[16] This feudal barony survives to this day.

Notable residents

The British politician Baroness Scotland of Asthal, the former Attorney-General for England and Wales, lives in Asthall.[18]

References

- "Asthall Parish Council Website". Asthall Parish Council. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Area: Asthal (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Watts, Victor (2010). The Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780521168557.

- Townley 2006, pp. 37–48.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 426.

- Henig & Chambers 1984, pp. 19–21.

- Rowley 1978, p. 104.

- "Asthall". Oxfordshire Churches & Chapels. Brian Curtis. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 424.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 425.

- Historic England. "Church of Saint Nicholas (Grade II*) (1053514)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Baldwin, John (24 May 2008). "Place: Asthall S Nicholas". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Dovemaster (25 June 2010). "Bell Founders". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Archbishops' Council. "Benefice of Burford Fulbrook Taynton Asthall Swinbrook and Widford". A Church Near You. Church of England. Archived from the original on 30 November 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Ashmolean acquires a hoard of angels". Media. Ashmolean Museum. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Bloch, M. (2014). Feudal society. Routledge.

- "The Maytime Inn". Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Tran, Mark (28 June 2007). "Profile: Lady Scotland". The Guardian. London.

Sources and further reading

- Booth, P.M.; Allen, Tim (1997). Asthall, Oxfordshire: Excavations in a Roman 'Small Town'. Thames Valley Landscape Series. Vol. 9. Oxford: Oxford Archaeology. ISBN 0-947816-87-9.

- Colvin, Christina; Cragoe, Carol; Ortenberg, Veronica; Peberdy, R.B.; Selwyn, Nesta; Williamson, Elizabeth (2006). Townley, Simon C. (ed.). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. Vol. 15: Carterton, Minster Lovell and Environs: Bampton Hundred (Part Three). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 37–72. ISBN 978-1-90435-606-6.

- Henig, Martin; Chambers, R.A. (1984). "Two Roman Bronze Birds from Oxfordshire" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. XLVIII: 19–21. ISSN 0308-5562.

- Rowley, Trevor (1978). Villages in the Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 104. ISBN 0-460-04166-5.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 424–426. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.