Stonesfield

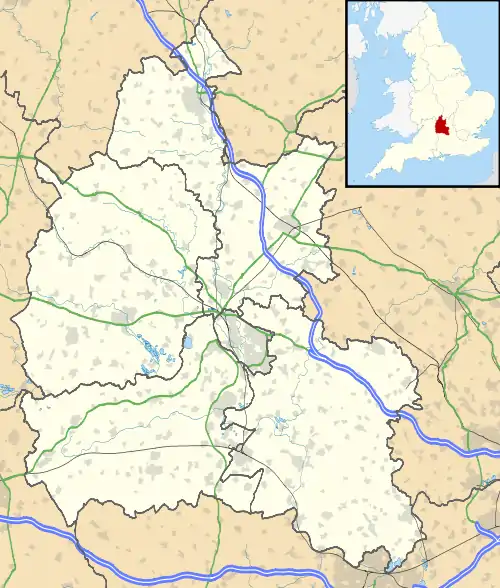

Stonesfield is a village and civil parish about 5 miles (8 km) north of Witney in Oxfordshire, and about 10 miles (17 km) north-west of Oxford. The village is on the crest of an escarpment. The parish extends mostly north and north-east of the village, in which directions the land rises gently and then descends to the River Glyme at Glympton and Wootton about 3 miles (5 km) to the north-east. South of Stonesfield, below the escarpment, is the River Evenlode which touches the southern edge of the parish. At the centre of Stonesfield stands the 13th-century church of St James the Great[1] as well as a Wesleyan chapel, Stonesfield Methodist Church, slightly further west.[2] The village is known for Stonesfield slate, a form of Cotswold stone mined particularly as a roofing stone and also a rich source of fossils. The architecture in Stonesfield features many old Cotswold stone properties roofed with locally mined slate along with some late 20th-century buildings and several properties under construction.[3] The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 1,527.[4]

| Stonesfield | |

|---|---|

| Village | |

Aerial view of the village | |

View of St James the Great parish church from The Cross | |

Stonesfield Location within Oxfordshire | |

| Area | 0.53 km2 (0.20 sq mi) (2011 Census) |

| Population | 1,527 (2011 Census) |

| • Density | 2881 |

| Area of civil parish | 513.38 sq km (198.22 sq mi) (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SP3917 |

| • London | 60 mi (97 km) |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Witney |

| Postcode district | OX29 |

| Dialling code | 01993 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Oxfordshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Stonesfield ~ Oxfordshire |

Literature

Poetry

Dr Romola Parish, an academic, lawyer, artist, and poet who studied Creative Writing at the University of Oxford has written two poems about Stonesfield during her time as poet in residence at Oxfordshire County Council, working as part of the Oxfordshire Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) project.[5] Both poems are from the collection In Polygonia and were both published in The Stonesfield Slate.[6] The first was published in April 2018 and was simply called ‘Stonesfield’ while the second was published in March 2020 on the back page of issue 500 of The Stonesfield Slate and had the title ‘Stuntesfeld’.[7]

Toponym

The Domesday Book of 1086 records Stonesfield as Stunsfeld, meaning "fool's field". This was because of the stony soil in the area, so the toponym's mutation is most appropriate. Thomas Hearne used the spelling "Stunsfield" in 1712[8] and Akerman spelt it "Stuntesfield" in 1854.[9]

Geology

Stonesfield is on the Taynton Limestone Formation, a type of Cotswold stone that until the 20th century was mined as a roofing stone called Stonesfield slate. It is common on roofs of older buildings in the Cotswolds and Oxfordshire. Many of the older buildings of the University of Oxford have Stonesfield slate roofs. The mines were also one of Britain's richest sources of Middle Jurassic vertebrate fossils. The first fossil bones to be identified as those of a dinosaur were found early in the 19th century near Stonesfield. They are part of the skeleton of a bipedal carnivore, and in 1824 the pioneering palaeontologist William Buckland named it Megalosaurus. The bones are now displayed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Other reptiles found at Stonesfield include the crocodile Steneosaurus, pterosaur Rhamphocephalus and the type specimen of the theropod genus Iliosuchus.[10] Also found here was the type specimen of the quadruped Stereognathus[10] belonging to the clade of animals called cynodonts, which were more like mammals than reptiles.

Archaeology

The course of Akeman Street Roman road forms part of the south-eastern boundary of the parish. In a field just east of the village is the site of a Roman villa that was very close to the Roman road. A tenant farmer, George Handes (or Hannes), found the villa in 1712 when his plough revealed the remains of a Roman pavement[8] dating from the 3rd or 4th century AD.[11] One of its panels showed the Roman god Bacchus riding a panther.[12] Handes' landlord, Richard Fowler of Great Barrington, Gloucestershire, did not welcome the discovery[8] and he quarrelled with Handes over any profit to be had from excavating and displaying the pavement.[13] The pavement immediately attracted the interest of the Oxford academic Thomas Hearne, soon followed by Bernard Gardiner.[14] However, in 1724 the pioneering archaeologist William Stukeley reported that Handes had destroyed the pavement as a result of the dispute with Fowler.[13] Nevertheless, in 1780 the antiquarian Daines Barrington reported that much of the room and pavement found in 1712 still survived and a second, smaller room with a tesselated floor was being excavated.[13] At the same time parts of the villa's baths were also excavated.[13] In 1789 Richard Gough reported in his new edition of William Camden's Britannia that much of the pavement had been destroyed.[11]

In 1801 Stonesfield's common lands were enclosed and the division of land caused further damage to the remains of the villa.[11] In 1813 the antiquarian James Brewer reported in the Oxfordshire volume of his The Beauties of England and Wales that only fragments of the pavement found in 1712 had survived destruction.[15] In 1826 the Ashmolean Museum acquired hypocaust flue-tiles from the site and the base of a pillar that may also be from the hypocaust.[9] In 1836 a small coin from the reign of the 4th-century Emperor Valentinian was found.[9] In 1858 a visitor called Akerman learnt that the remains of the villa had been totally destroyed.[9] During the Second World War aerial archaeology discovered a number of Roman and other archaeological sites in this part of Oxfordshire. However, despite repeated attempts in different seasons and under different crop conditions, aerial archaeology has found no surviving trace of the villa at Stonesfield.[9] About 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Stonesfield, on the other side of the River Evenlode and in the next parish, the remains of North Leigh Roman Villa survive in the care of English Heritage.

Church and chapels

Church of England

The Church of England parish church of St James the Great was built in the 13th century. Surviving Early English features from that period include the chancel arch, north chapel, south aisle, arcade and piscina[16] and most of the west tower.[17] Decorated Gothic remodelling in the 14th century includes the piscina and south windows of the chancel, the north window and west arch of the north chapel and the east window of the south aisle.[16] The octagonal font is also 14th-century.[17] In the 15th century the west tower was increased in height.[18]

Between the chancel and north chapel is a screen that is partly Perpendicular Gothic. The Perpendicular Gothic east window in the chancel is 15th-century. Fragments of 15th-century stained glass survive in the window, including a figure that has a 14th-century head and may represent Saint Peter, and symbols of the evangelists St John and St Mark. In the west window of the west tower is late-15th-century stained glass of four family coats of arms. In one of the south windows of the chancel is 16th-century stained glass of two coats of arms: one of a manorial family and the other of the Worshipful Company of Mercers. There is also mid-16th-century stained glass of two family coats of arms in one of the 17th-century south windows of the clerestory. The Jacobean pulpit was made in 1629.[17]

In 1743 a clock was installed in the church.[19] It was said to have been made for a local manor house in 1543, and transferred to the church after the house was demolished.[19] The clock has since been moved from Stonesfield, rebuilt, and installed at Judd's Garage at Wootton.[19] In 1825 the north aisle was greatly enlarged,[18] opening directly into the nave without an arcade. This greatly changed the interior of the church, and in the 20th century the architectural historians Jennifer Sherwood and Sir Nikolaus Pevsner condemned the change as "lunatic". Other 19th-century changes include the addition of the south porch, possibly during a restoration in 1876.[16] The vestry was added in 1956. The church is a Grade II* listed building[18] St James' parish is now part of the Benefice of Stonesfield with Combe Longa.[20]

Methodist

Stonesfield Methodist Church is a Wesleyan chapel with capacity for 100 people, located at the junction of Boot Street and High Street.

The current church was first opened for worship in July 1867 and still remains in use today. The current Reverend is Rev Rose Westwood, Witney and Farringdon Circuit Superintendent and Minister for Long Hanborough, Charlbury, Stonesfield, and Sutton Churches.[21]

The church contains a four and a half octave single keyboard organ with foot pedals and seven stops.[22] It bears two plaques recording two last members who helped arrange for its purchase and installation; both plaques are dedicated to the Glory of God 30 April 1966.[22]

Economic and social history

For centuries the parish had one main open field for arable farming: Home Field, which was east of the village. Three others, Church Field, Callowe, and Jenner's Sarts, were much smaller,[23] and an early 17th-century survey records that not every farmer had strips in Church Field.[24] In 1232 the parish almost doubled in size by acquiring King's Wood, a nearby detached part of Bloxham parish. It was in this wood that people from Stonesfield created Callowe by clearing woodland, a process called assarting. By the time of the Hundred Rolls in the 1270s, every tenant in Stonesfield held assarted land.

By the first decade of the 17th century Stonesfield had at least four fields. Church Field is taken to be ancient like Home Field,[23] but Jenner's Sarts was created by felling in Gerner's Wood.[23] It is not clear whether this field is the same as that called Gannett's Sarte in another source.[25] By 1792 very little of Stonesfield's common land had been enclosed, and most of it was still worked by arable strip farming. By 1797 most of this had been enclosed and converted to pasture. Some common land remained in the parts of the parish closest to the village,[23] but this was enclosed in a land award of 1804.[24]

Amenities

Public houses

Over the years Stonesfield has had between seven and ten pubs; however, since 2020 the village no longer has any active pubs or restaurants.[26]

The White Horse

The White Horse, Stonesfield's final pub, was at the top of the village green on The Ridings.[27] The pub had served the community since its opening in 1876.[28] Previously called the White Lion, a man named John Lardner held its licence from 1847 and resided in one of the three cottages making up the pub's buildings.[29] Following John's death in September 1865 the licence was transferred to his son, Henry Lardner, in October 1865.[29] This was the first mention of the name 'White Horse'. The White Horse was sold at auction after it was advertised on 28 October 1876.[30] The listing had the description: 'A stone-built and slated free public house, called or known by the name of "The White Horse," situate in the village of Stonesfield, and containing 2 front rooms, tap room, pantry, scullery, cellar 3 bed rooms, and 1 attic; together with the 2 Cottages adjoining (but unoccupied). Detached are a Brew-house, large Shop with extensive cellarage underneath, Stable, Barn, Wagon Hovel, Cow Shed, Poultry Pen, Piggery, and Cattle Yard; together with capital Garden Ground at the back and in the front of the house.

The Outgoings are Quit Rents amounting to 1s. yearly.'.[31] From 1876 to 1907 various landlords took on the role of running the pub until the licence was passed on to the Oliver family. The family ran it from 1907 under Edward Oliver until 1962 under Minnie Oliver.[31] The Witney Gazette referenced Vivian and Emily Miles' retirement from the pub's ownership in June 1977.[31] During the 1980s Nigel Bishop ran the White Horse. During this period, much like Sturdy's Castle on the Banbury Road (A4260) and the King's Head in the centre of Woodstock, the White Horse Inn became a 'Spud Pub'. After a period between 2001 and 2005 of the pub being shut, it was bought by a Londoner called Richard Starowki.[29] Following restoration he reopened The White Horse in 2006. Three years later, in 2009, John Lloyd bought the pub from Richard.[29] During the March 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in England, the pub was forced to close and never reopened.[28] The owner, John Lloyd, listed it for sale that July.[32] Local residents formed a community benefit society to attempt to raise money to save the pub via a shared ownership concept.[33] £430,000 was eventually raised.[34] Despite this, a private sale took place in early 2021.[27] The new owner says he plans to reopen the pub; however, concerns have arisen from his background as a property developer.[26]

The Black Head

Originally named The Black Boy, The Black Head was a pub on Church Street. The pub burnt down in around 1850 during which time Thomas Stewart had ownership.[31] This was the cause of the name change to The Black Head when it was rebuilt soon afterwards, the name sticking until the pub ceased trading in 2010.[35] During the 21st century the pub was owned by the Nomura Bank of Japan, owner of the Wellington Pub Company.[31] Its latest owner applied in 2012[36] and 2014[37] for planning permission to turn the Black Head into a private house. The building is now a private residence.[38]

The Chequers

The Chequers is another pub in the village that is now a private residence. It was on the south of Laughton's Hill and was allegedly a popular pub with entertainers travelling through Stonesfield. The Chequers was open from 1753 until 1847.[31]

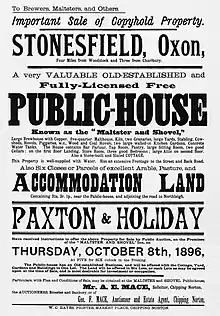

The Malster and Shovel

The Malster & Shovel, on High Street, was open from 1831 to 1939 and is now also a private residence.[31]

The Marlborough Arms

A public house which now forms part of Prospect Villa, The Marlborough Arms, opened on the Woodstock Road in 1838 and served customers until 1875.[31]

The Rose and Crown

The Rose & Crown also previously stood on the High Street; however, it was demolished in 1958[31] to make way for a new school playground and, 34 years later, five low cost houses were erected there.[26]

The Swan Inn

The Swan Inn is thought to have been up the Tewer and served from around 1865 until 1877,[41] although evidence is limited especially compared to the other Stonesfield pubs.

The Churchill Arms

The Churchill Arms is another public house with limited information regarding its details. The Oxford Journal mentioned the pub in 1826 and 1828 regarding the auction of an 'estate at Stonesfield'.[42]

The Boot Inn

The Boot Inn was also among Stonesfield's previous pubs.[26] Mr Vivian Miles and his wife, Emily, ran the pub from 1952 until 1962 before taking ownership of the White Horse Inn up the road for a further 15 years.

The Pick and Hammer

The Pick and Hammer pub is said to have been at the bottom of Well Lane. Records are also limited in regard to this pub; however, the cottage gained notoriety in the 1990s from a police incident involving a search for the body of a murdered woman. Michael Morton, a millionaire and architect by trade, was jailed for seven years in 1997 following his conviction of the murder of Gracia, his 40-year-old wife.[31]

Village hall and Stonesfield Sports and Social Club

Stonesfield Village Hall is at the end of Field Close, next to the library, play park, and football pitch. Stonesfield Sports & Social Club opened on 23 July 1995 after 10 years of fundraising £65,000 for an extension to the village hall.[31] The Main Hall can accommodate up to 200 people.[43] The community hall contains a stage, small 50-capacity club room, kitchen and has a car-parking area outside. Stonesfield Parish Council meetings are regularly held at the village hall.[44] The library next door, Stonesfield Library, is a small community library run by Oxfordshire County Council and supported by the Friends of Stonesfield Library (FoSL).[45]

Sports pitch and playground

The adjacent 7-acre (2.8 ha) sports pitch accommodates cricket and football matches as well as three tennis courts in the far north corner.[46] This is the home ground of Stonesfield Strikers F.C., a youth football club with a number of mixed-sex and girls-only teams.[47] The club is FA Charter Standard and is affiliated with Oxfordshire FA, boasting teams in all local leagues.[47] They also fundraise for the Mickey Lewis Memorial Fund in memory of the club mentor and coach.[48]

There is also a small playground, Stonesfield Play Park, next to the library and sports pitch. The playground is fully grassed and has equipment such as three slides, five swings, and a zip line on a small mound.[49]

Stonesfield Tennis Club is a community tennis club which was established more than 50 years ago. The club's relatively small, friendly group of members play on the aforementioned tennis courts on the sports pitch, which were re-laid in 2018.[50]

Stonesfield Cricket Club, also known as Stonesfield CC, are a community cricket club which play on Stonesfield's sports field each season.[51] The club has a 1st XI, 2nd XI, under 15, under 13, and indoor team.[52] Stonesfield CC beat East & West Hendred in 2005 to win the Telegraph Cup. The 2nd XI also won the Keith Crump Centenary Cup by beating Hook Norton 2nd XI in 2007's final.[53]

Village shop

Stonesfield's village shop, Suriya Express, is located in Pendle Court in the centre of the village and is a Best-one store. It was previously known as Amlu's General Store, from the Tamil word ‘Amlu’, meaning ‘darling’.[54] The shop was run by Sri Vairamuthu and his family for over ten years before they moved to London.[54] During this time the shop was voted best Oxfordshire village shop in 2006.[54] The shop is now run by Mathon Sabapathy and his wife.[54] The shop now contains a Royal Mail post office following its move from next to St James the Great Church.[55] Adjacent to the shop is a hairdresser called Salon Copenhagen.[44]

Primary school

Stonesfield Primary School is a community primary school located in the centre of the village on the High Street. It caters for pupils age 4 to 11 from the ward of Stonesfield and Tackley and has capacity for 150 students.[56] Its current headteacher is Ben Tevail and there are currently over 100 students.[57] The approximately 68,000 square feet (6,300 m2) sports field and playground behind the school, backing onto Peaks Lane, form an iconic part of the village.[58]

Garage

Stonesfield Garage is situated on The Ridings in the north east of the village, near to The White Horse Inn. The garage opened in December 2015,[59] selling, servicing, and repairing vehicles. The garage specialises in Volkswagen and Audi but offer services for a wide range of vehicles.[60]

St James’ Centre

Found on the High Street opposite Stonesfield Primary School and behind St James the Great Church, The St James’ Centre, previously the village school, is used for exhibitions, workshops, education classes for adults, meetings, family gatherings, fundraising events and children’s parties.[44] The centre belongs to Stonesfield Parish Church and sits on the edge of the church’s grounds. The modernised centre includes a main hall, kitchen, sitting room, patio, 3 smaller rooms, garden, and a car park.[61]

Callow Farm Shop

Callow Farm Shop was a farm shop and Cotswold country house located on Callow Farm, Stonesfield's northernmost farm located on Stonesfield Riding, 0.64 miles (1,030 m) from the B4437.[62] The farm shop was run by Dave Holloway and offered a range of produce ranging from home reared meat to freshly harvested vegetables however it was well known for its free range Bronze Christmas Turkeys which are still sold every Christmas.[63] The farm shop permanently closed on 30 April 2015 mainly due to financial pressures.[64] The holiday accommodation remains functional with Laughton's Retreat sleeping 4 guests and Harvest Barn sleeping 12.[62]

Allotments

Stonesfield Allotment Association, chaired by Jon Gordon, controls the allotments within the village. Churchfield Allotment is an allotment in the south of Stonesfield extending down into Stonesfield Common. The allotment's plot is about 473 feet (144 m) in length by 95 feet (29 m) in width. Having raised over £3000, in February 2019 the allotment holders helped to instal the infrastructure needed for four new water troughs to be installed to supply the allotment with fresh water via the Thames Water network.[65] The second, slightly smaller allotment plot is the Woodstock Road site located in the north east reaches of Stonesfield, surrounded by fields.[66]

1st Stonesfield Scouts

1st Stonesfield Scouts are a Beaver, Cubs and Scout group running in Stonesfield since 1948.[67] The group caters for local children between the ages of 6 and 14 and has over 100 members with some getting put on a waiting list due to high demand.[68] The Stonesfield Scout Hut, known as Andy's Den, was in Stonesfield Common’s woods at Stockey Bottom and could be found by taking a path off Church Fields opposite St James the Great Graveyard in the south west of Stonesfield.[69] The scout hut was originally temporary wartime accommodation at RAF Bicester. In 1958 it was dismantled and transported via lorry to its new location.[67] The site was demolished and cleared in late 2019 due to factors such as asbestos related health concerns, rodent infestations, and inadequate facilities.[70] The group now aim to build a new Outdoor Education and Environmental Wellbeing Centre, fundraising for a target of £175,000.[67]

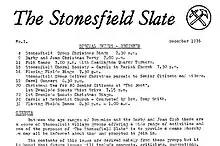

The Stonesfield Slate

The Stonesfield Slate, often known simply as the Slate, is Stonesfield's monthly village magazine named after the famous slate found in the village. It is produced and delivered by volunteers. All residents of the village have the option of being delivered a copy every month for free although physical copies are also available at the village shop and library and a digital archive of all issues can be found on Stonesfield's official Parish Council website.[71] The Bodleian Library, who believe the Slate to be one of the longest running local magazines, keeps copies of the publication for its archive.[72]

The Slate was founded in December 1976 by Gordon Rudlin who wanted a newsletter which gave details about village events as he kept hearing about things after they had taken place.[72] There have been four publishers since 2020.[73] Richard and Dale Morris took over from Gordon in January 1998 and held the publisher role for the next seven years, bringing the publication fully into the digital age.[74] Jenny and Simon Haviland were presented with a framed Stonesfield slate on 29 February 2020 to celebrate the 500th issue of the publication and recognise their efforts as publishers of the magazine since 2004.[72] In response to the Havilands stepping down, Diane and Paul Bates took over as publishers from January 2020.[72] The front page of each issue formerly had the words "With or without offence to friends or foes We sketch your world exactly as it goes."[74] Since the personal computer hadn't been invented yet, the Slate was originally typed on a mimeograph stencil on a manual typewriter.[74] To get the project going, Rudlin asked the Village Hall committee and various village residents for sponsorship and to volunteer as editors, typists, printers and deliverers.[74] For many years Rachel Sherlaw Johnson's illustrations were included in small otherwise empty spaces in each issue of the magazine.[74] On 15 June 1990 the publication won a certificate of merit in the Oxfordshire Village Ventures Competition 1988–89.[74] The Slate had a full page photographic cover for the first time to celebrate the start of the new millennium. It was by luck that it happened to snow the day of the deadline for that issue. January 2009 is the only other time a photographic cover has been used.[74]

Other

There was previously a skittle alley at the top of Pond Hill on The Ridings, next to The White Horse pub.[26] Its owner, John Lloyd, received opposition to his plans to turn it into a house next to the pub which he also owned.[26] The skittle alley is no longer present.

Stonesfield also has a Women's Institute with meetings being held monthly in Stonesfield Village Hall.[75]

Transport

Train

The nearest railway station, Finstock railway station, is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) away in the nearby village of Finstock on the Cotswold Line.[76] There is an alternative train service to London from Oxford Parkway on Chiltern Railways.[77]

Bus

.jpg.webp)

Stonesfield has four main bus stops: Combe Road, Prospect Close, Boot Street, and Green which are all used by Stagecoach S3 gold[78] and 7 gold[79] buses as well as The Villager V26 bus.[80] The S3 and 7 provide the hourly bus service between Charlbury, Woodstock and Oxford which serves Stonesfield.[81] Worths' Coaches of Enstone operated the route from the 1920s until 2004, when Oxfordshire County Council awarded the contract to Stagecoach in Oxfordshire.[82] The Villager community bus service operates the V26 route between Oddington and Witney via Stonesfield.[80] The V26 bus operates on a Monday, Tuesday and Friday only and departs from Stonesfield once in the morning, returning later in the day in the early afternoon.[80]

.jpg.webp)

Other

Stonesfield Voluntary Transport Scheme uses volunteer drivers to allow residents to get to medical facilities such as Woodstock Surgery, John Radcliffe Hospital, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre in Oxford, and Horton General Hospital in Banbury free of charge.[83][84]

Stonesfield is on the Oxfordshire Way long-distance footpath, which runs for 66 miles (106 km) from Bourton-on-the-Water to Henley.[85] The Oxfordshire Cotswolds' Step into the Cotswolds walk three is a 6.5 miles (10.5 km) route through Combe and Blenheim Great Park, starting and ending in Stonesfield.[86] Stonesfield also features in the AA’s rated trips with a 3.5 miles (5.6 km) 1.5-hour long walk through the village and south west of the parish down to the River Evenlode.[87] Oaklands Farm Airstrip lies in a field on the outer south west regions of Stonesfield.[88] It's a 400-metre long, 12-metre wide, grass, private airstrip in one of Oaklands Farm's crop fields.[89] The airstrip is thought to have featured in a flight sequence in the 2009 British film 31 North 62 East.[89]

Notable people

- Ed Atkins, an artist and teacher at Goldsmiths College London, famous for his multimedia poetry and video installations,[90] was raised in Stonesfield.[91]

- Rev. Walter Brown, rector of Handborough and St James the Great Church in Stonesfield, chaplain and librarian at Blenheim, held two residences but resided in Stonesfield in the early 1800s.[92] Walter is credited with repairing the paving and the west end of the chancel of St James the Great Church.[92] He privately educated British army officer Sir Augustus Almeric Spencer.

- Chris Davies, artist and runner-up in series 3 of the BBC One TV programme and competition The Big Painting Challenge, lives in the village.[93][94]

- Basil Eastwood, British Ambassador (Syria 1996–2000; Switzerland 2001–2004), lived in Stonesfield until retirement,[95] and founded the charity Cecily's Fund in the village.[96] A Cecily's Day picnic is held every year on the lawns of Stonesfield Manor.[97]

- Rupert Friend, actor, director, screenwriter and producer. Raised in Stonesfield and good friends with Ed Atkins.[98][99]

- Nicholas Timothy Hooper, BAFTA award-winning composer, has lived in Stonesfield since the 1980s.[95] Nick, his wife Judith Marjorie Inez Hooper, and Susana Starling make up The Boot Band: a folk music trio.[100] He runs his company, Nicholas Hooper Music Limited, from Sanders Gate, Churchfields.[101]

- Robert Sherlaw Johnson,[102] composer, lived in Stonesfield from the late 1960s until his death in 2000.

- Caroline Lucas, former leader of the Green Party of England and Wales, lived in Stonesfield until her election as an MEP in 1999. She owned this house in Stonesfield for five years.[103]

- Walter Padbury, the Australian pioneer and philanthropist who arrived in Western Australia in February 1830, was born in Stonesfield.[104]

- Gordon Rudlin, founder of The Stonesfield Slate village magazine in December 1976 and financial officer for Oxfam in Oxford for 13 years.[105] Died at the age of 97 in 2005.[106]

- Sir William Strang, 1st Baron Strang of Stonesfield (1893–1978), succeeded by his only son Colin Strang. Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (1949–1953) and subsequently the first Convenor of the Crossbench peers in the House of Lords from 1968 to 1974.[107][108]

Citations

- "History of the Church". Stonesfield Parish Church. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Methodist Church". West Oxfordshire Community Web. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "About Stonesfield". Stonesfield Village Official Parish Council Website. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "Area: Stonesfield (Parish): Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- "CARM – Leaders". carmretreats.org. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Poetry". Romola Parish. 24 August 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Poem about Stonesfield". Stonesfield Parish Council. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Taylor 1941, p. 1.

- Taylor 1941, p. 8.

- "Key geological sites: West Oxfordshire". Oxford Geology Group. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Taylor 1941, p. 7.

- Taylor 1941, p. 9.

- Taylor 1941, p. 6.

- Taylor 1941, p. 1–3.

- Taylor 1941, p. 7–8.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 790.

- Sherwood & Pevsner 1974, p. 791.

- Historic England. "Church of St James The Great (Grade II*) (1053074)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Beeson 1989, p. 67.

- Archbishops' Council. "Benefice of Stonesfield with Combe Longa". A Church Near You. Church of England. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Witney & Faringdon – Welcome Service for Rev Rose Westwood". westoxfordshiremethodists.org.uk. 16 August 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Methodist Church". wospweb.com. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Baggs et al. 1983, pp. 181–194

- Gray 1959, p. 510.

- Gray 1959, p. 84.

- Segal, David (28 November 2020). "Closing Time for a Village's Last Pub?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Rice, Liam (14 October 2021). "Oxfordshire village calls for owner to sell White Horse pub". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "About". The White Horse, Stonesfield. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "History". The White Horse Stonesfield community action group. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Rudlin, Douglas. A Brief History of the White Horse, Stonesfield (PDF). p. 1.

- Rudlin, Douglas (2020). The Life and Times of the Inns, Taverns and Beerhouses at Stonesfield, Oxfordshire.

- "Last Minute Extension Given to Raise £480,000 for White Horse in Springfield to Save It From Developers After Global Support". Ox in a Box. 1 December 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "STONESFIELD COMMUNITY PUB overview – Find and update company information". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- Everett, Flic (30 November 2020). "How the fight to save a tiny Cotswolds pub sparked a frenzy of transatlantic interest". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- "Shut-down Stonesfield pub could become house". Oxford Mail. Newsquest. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Planning >> Application Summary 12/1126/P/FP". West Oxfordshire District Council. 16 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Planning >> Application Summary 14/1173/P/FP". West Oxfordshire District Council. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Black Head, Stonesfield". whatpub.com. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- Rudlin, Douglas. The Life and Times of the Inns, Taverns and Beerhouses of Stonesfield, Oxfordshire. p. 21.

- Rudlin, Douglas. The Life and Times of the Inns, Taverns and Beerhouses of Stonesfield, Oxfordshire. p. 9.

- "License granted to Joseph Kirby for the Swan Inn, Stonesfield". Oxford Times. 2 September 1865.

- "Churchill Arms, Stonesfield". Oxford Journal. 1828.

- "Stonesfield Village Hall". Hallshire.com. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "Life". Stonesfield Parish Council. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Library". Oxfordshire County Council.

- Ruby. "Stonesfield play park, Stonesfield, Oxfordshire". freeparks.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- Stonesfield Strikers FC

- "Mickey Lewis | Stonesfield Strikers". Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Play Park – The Family Ticket Review". The Family Ticket. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Tennis Club". Stonesfield Tennis Club. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Stonesfield CC". stonesfield.play-cricket.com. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Stonesfield CC". stonesfield.play-cricket.com. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Cherwell Cricket League – Club Performance History". cherwellcricketleague.com. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "Fond farewell to much-loved village shopkeeper". Oxford Mail. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Branch Finder | Post Office". www.postoffice.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Primary School – GOV.UK". get-information-schools.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Oxfordshire County Council". oxfordshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Primary School – Learning together to achieve our best". stonesfield.oxon.sch.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "STONESFIELD GARAGE LLP overview – Find and update company information – GOV.UK". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Garage".

- "St James' Centre – Stonesfield Parish Church". Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Callow Farm Shop | How to find Callow Farm". callowfarm.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Callow Farm Shop | Product Lists". www.callowfarm.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Callow Farm Shop's Sad News". callowfarm.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Water coming to Churchfield Allotment". Stonesfield Parish Council. 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Allotment plot available". Stonesfield Parish Council. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Scout Hut". Just Giving. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Scouts". Stonesfield Scouts. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Scouts in £100k rally for new hut". Oxford Mail. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Scout Hut – Farewell old friend!". Stonesfield Parish Council. 29 November 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Life". Stonesfield Parish Council. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- Kendall, Viv (April 2020). "The Stonesfield Slate, Issue No 501". The Stonesfield Slate. p. 1.

- Morris, Dale (March 2020). "The Stonesfield Slate, Issue No 500". The Stonesfield Slate. p. 3.

- Morris, Dale (March 2020). "The Stonesfield Slate, Issue No 500". The Stonesfield Slate. pp. 24–25.

- "Your Nearest WI". Oxfordshire Federation of Women's Institutes. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Finstock Train Station | Train Times | Great Western Railway". www.gwr.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Oxford Parkway to London Trains | Trains To London | Chiltern Railways". www.chilternrailways.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "S3 Bus Route & Timetable: Oxford – Chipping Norton | Stagecoach". www.stagecoachbus.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "7 Bus Route & Timetable: Oxford – Woodstock | Stagecoach". www.stagecoachbus.com. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "The Villager Bus Timetables". The Villager Bus. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Oxford – Chipping Norton Service S3" (PDF). Stagecoach in Oxfordshire. 27 July 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Family firm loses out in bus route shake-up". Oxford Mail. 2 November 2004. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Voluntary Transport Scheme – Oxfordshire". livewell.oxfordshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield Voluntary Transport Scheme – Restarting". Stonesfield Parish Council. 7 February 2022. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Oxfordshire Way". Long Distance Walkers Association. n.d. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Free Downloadable Walks – Oxfordshire Cotswolds". oxfordshirecotswolds.org. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield and its slate mining history". AA RatedTrips.com. 19 March 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- "Oaklands Farm Airstrip Airport – AG5189 – Airport Guide". AirportGuide. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Oaklands Farm Oxon – UK Airfield Guide". ukairfieldguide.net. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- "Meet Ed Atkins". Faculty of Contemporary Arts. 27 March 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Maddox, Georgina (9 October 2019). "Contemporary artist Ed Atkins' latest works showcased at the Venice Biennale". Stir World. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Parishes: Stonesfield | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "BBC One – The Big Painting Challenge – Meet the 2018 contestants". BBC. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "BBC One – The Big Painting Challenge, Series 2, Final". BBC. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Stonesfield". whatsonoxon.co.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Cecily's Fund helps orphans in Africa". Witney Gazette. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Cecily's Fund is holding annual picnic". Witney Gazette. September 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Ornos, Riza (24 February 2015). "'Agent 47' News Update: Paul Walker Replacement Rupert Friend First Images Released, Five Things to Know About the 'Homeland' Actor". International Business Times. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Rupert Friend talks Hitman, blagging and Homeland". The Independent. 21 August 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "The Boot Band". Word and Note. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "NICHOLAS HOOPER MUSIC LIMITED overview – Find and update company information – GOV.UK". find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- "Obituary: Robert Sherlaw-Johnson". The Guardian. 16 November 2000. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Caroline Lucas' speech to the CPRE". greenparty.org.uk. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- Cara Cammilleri, 'Padbury, Walter (1820–1907)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, MUP, 1974, pp 388–389.

- "Celebration of Slate 500th issue". Stonesfield Parish Council. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- "Healthy pointers to a very long life". Oxford Mail. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- The Papers of William Strang, 1st Baron Strang of Stonesfield, K.C.B. <persname>Strang, William, 1893–1978, 1st Baron Strang of Stonesfield, diplomat</persname>. 1916–1978.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - House of Lords Hansard. Vol. 185. UK Parliament. 1954.

General and cited sources

- Baggs, A. P.; Colvin, Christina; Colvin, H.M.; Cooper, Janet; Day, C.J.; Selwyn, Nesta; Tomkinson, A. (1983). Crossley, Alan (ed.). A History of the County of Oxford. Victoria County History. Vol. 11: Wootton Hundred (northern part). London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 181–194. ISBN 978-0-19722-758-9.

- Beeson, C. F. C. (1989) [1962]. Simcock, A.V. (ed.). Clockmaking in Oxfordshire 1400–1850 (3rd ed.). Oxford: Museum of the History of Science. p. 67. ISBN 0-903364-06-9.

- Gray, Howard L (1959) [1915]. The English Field Systems. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press; Merlin Press. pp. 84, 510.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 790–791. ISBN 0-14-071045-0.

- Taylor, M. V. (1941). "The Roman Tessellated Pavement at Stonesfield, Oxon" (PDF). Oxoniensia. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society. VI: 1–8.