Astypalaia

Astypalaia (Greek: Αστυπάλαια, pronounced [astiˈpalea]), is a Greek island with 1,334 residents (2011 census). It belongs to the Dodecanese, an archipelago of fifteen major islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea.

Astypalea

Αστυπάλαια | |

|---|---|

Astypalaia (harbour) | |

Astypalea Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 36°33′N 26°21′E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | South Aegean |

| Regional unit | Kalymnos |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 114.1 km2 (44.1 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 506 m (1,660 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Municipality | 1,334 |

| • Municipality density | 12/km2 (30/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 859 00 |

| Area code(s) | 22430 |

| Vehicle registration | ΚΧ, ΡΟ, ΡΚ |

| Website | astipalea |

The island is 18 kilometres (11 miles) long, 13 kilometres (8 miles) wide at the most, and covers an area of 97 km2.[2] Along with numerous smaller uninhabited offshore islets (the largest of which are Sýrna and Ofidoussa), it forms the Municipality of Astypalaia, which is part of the Kalymnos regional unit. The municipality has an area of 114.077 km2.[3] The capital and the previous main harbour of the island is Astypalaia or Chora, as it is called by the locals.

Name

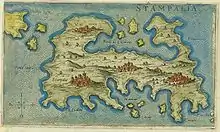

Astypalea was believed to be named after Astypalaea, an ancient Greek mythological figure. The island is known in Italian as Stampalia and in Ottoman Turkish as İstanbulya (استانبوليه)

Geography

The coasts of Astypalaia are rocky with many small pebble-strewn beaches. A small band of land of roughly 126 metres wide almost separates the island in two sections at Stenó.

A new harbour has been built in Agios Andreas on the mid island from where now the connections are west and east with Athenian port of Piraeus and the other islands of the Dodecanese. Flight connections with Athens are available from the airport close to Maltezana.

Places

- Villages : Astypalea or Chora (pop. 1,036), Analipsi or Maltezana (149), Livadi (39), Vathi (14)

- Islets : Agía Kyriakí, Astypálaia, Avgó, Glynó, Zaforás, Kounoúpoi, Koutsomýti, Mesonísi, Ofidoússa, Plakída, Pontikoúsa, Stefánia, Sýrna, Fokionísia, Khondró, Khondronísi (all uninhabited except Astypálaia itself)

History

.jpg.webp)

In Greek mythology, Astypalaia was a woman abducted by Poseidon in the form of a winged fish-tailed leopard.[4] The island was colonized by Megara or possibly Epidaurus, and its governing system and buildings are known from numerous inscriptions.[5] Pliny the Elder records that Rome accorded Astypalaia the status of a free state.[6] It was assigned to the Aegean Roman province of Insulae.

During the Middle Ages it belonged to the Byzantine Empire. It is presumed that it was conquered by the Latins in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in the early 13th century, but this is not documented. The island, known as Stampalia by the Latins, is mentioned for the first time in 1334, during a devastating raid by the Turkish ruler Umur of Aydin.[7] It was only shortly before this raid that the Venetian nobleman Giovanni Querini had purchased the island, declared himself its lord, and built a castle and a palace there.[7] The Querini held the island until 1522, and added the name of the island to their family name, which became Querini Stampalia. Astypalaia was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1522, and remained under Ottoman control until 1912, with two interruptions: from 1648 until 1668, during the Cretan War, it was occupied by Venice, and from 1821 to 1828 during the Greek War of Independence, when it was part of the provisional Greek republic.

On April 12, 1912, during the Italo-Turkish War, a detachment of the Regia Marina landed on Astypalaia, which thus became the first island of the Dodecanese to be occupied by Italy. From there the Italians, on the night between the 3rd and 4 May, landed on Rhodes.[8] The island remained under Italian governance until World War II. In a September 1943 naval battle near Astypalea, the Greek destroyer Vasilissa Olga together with the British destroyers HMS Faulknor and Eclipse sank a German convoy, consisting of the transports Pluto (2,000 tons) and Paolo (4,000 tons).

In 1947, through the Treaty of Paris, it became part of Greece along with the rest of the Dodecanese island group.

Archaeology

The religious and political center of the classical city-state of Astypalaia was the hill crowned by the Querini castle. The modern town of Chora occupies the same site, and worked stones from ancient monuments are reused in older houses as well as the castle. A one-room museum at Pera Gialos, on the shore near the old port, displays inscriptions, grave monuments, and other artifacts from the island. The earliest material on display is fragments of neolithic pottery. One case contains intact pottery, bronze weapons, and stone tools from a pair of richly furnished Mycenaean chamber tombs excavated at Armenochori (approximately 0.5 km (0.3 mi) west of the chapel of Agios Panteleimonas).

At Kylindra, on the west flank of the castle hill, a unique graveyard has been excavated by the Greek archaeological service. At least 2700 newborns and small children, below the age of two, were buried in ceramic pots between approximately 750 BC and Roman times. Since 2000, a team from University College London has undertaken systematic study of these remains and those of a contemporary cemetery for adults and older children excavated at Katsalos nearby.[9]

Kylindra was first excavated in 1996 by the 22nd Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities, who dated Kylindra from the Late Archaic to the Early Classical periods, and is also the largest child and infant cemetery in the world. They dated the nearby adult cemetery, Katsalos, from the Geometric to the Roman Period. Skeletal remains of infants are rare amongst most cemetery excavations; Ancient Greeks buried their infants in trade pots, such as amphorae, which contributed to the preservation of the remains from Kylindra. The collection of child and infant remains is currently housed at University College London, where the growth and development of the children and infants through development of tissues, bones, teeth structures are studied.[10]

The well-preserved mosaic floor of an early Christian basilica, decorated with geometric designs, lies underneath the chapel of Agia Varvara about 700 meters north of the small port of Analipsi (Maltezana). Its monolithic columns and marble column bases were evidently reused from a Hellenistic or Roman-period religious building nearby. A few meters east of the harbor of Analipsi, at a site known as Tallaras, are the remains of a late Roman-era bath. Its mosaic floors, including a Helios surrounded by the signs of the Zodiac, have been reburied by the Greek Archaeological Service (as of 9/2013), but photographs are on display at the museum. Mosaic floor fragments remain in situ at the ruined early Christian basilicas of Karekli (Schoinountas) and Agios Vasilios (south of Livadi).

Road signs lead to the inconspicuous, inaccessible remains of a pre-Venetian fortification on Mt. Patelos opposite the monastery of Agios Ioannis at the western extreme of Astypalaia.[11]

Treaty with Rome

Astypalaia's treaty with Rome, made in 105 BC, has survived in an inscription found on the island.[12] A noteworthy feature of this treaty is its formal assumption of sovereign equality between Rome and Astypalaia: the Astypalaians would not aid the enemies of the Romans or allow such enemies passage through their territory, and likewise the Romans would not aid the enemies of the Astypalaians or allow such enemies passage through their territory; in case of an attack on Astypalaia, the Romans would come to its aid, in case of an attack on Rome the Astypalaians would come to its aid; etc. Rome at the end of the second century BC still maintained the forms - if not the substance - of reciprocity in its dealings with Greek city-states. Since there was no reason for the Romans to single out Astypalaia for such formal courtesy, it is assumed that this treaty followed a standard formula used in treaties with other Greek city states, whose texts did not survive.

Electric island

In 2023, the Greek government announced an agreement with the Volkswagen Group to transform Astypalea into "a model island for climate-neutral mobility", as a laboratory for developing sustainable mobility. Substantial grants will be given to replace cars and vans with electric vehicles, and ride-sharing and demand-responsive transport will be introduced. To support this, a 3.5 megawatt photovoltaic power station with battery storage will be built.[13][14]

Ecclesiastical history

Astypalaea became a Christian bishopric and is mentioned as such in a 10th-century Notitia Episcopatuum.[15] It was a suffragan of the Metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Rhodes, the capital of the Aegean Insulae province.

Titular Latin Catholic see

As a diocese that is no longer residential, it is listed in the Annuario Pontificio among titular sees.[16]

In 1933 it was nominally restored Titular bishopric under the name of Astypalæa.

It has been vacant for decades, having had a single incumbent of the lowest (episcopal) rank :

- Titular Bishop James Buis, Mill Hill Missionaries (M.H.M.) (1952.02.14 – 1980.04.24), Apostolic Vicar of Kota Kinabalu (Malaysia) (1947.01.18 – 1972).

Notable people

- Onesicritus (c.360-c.290 BC), historian

- Frank Skartados (1956-2018), American politician and businessman

- Evdokia Anagnostou Professor and inaugural Dr. Stuart D. Sims Chair in Autism at the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital, Canada Research Chair in Translational Therapeutics in Autism Spectrum Disorder.

See also

References

- "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Astypalaia" in The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 651.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- Theoi.com

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Astropalia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 819.

- Gary Reger, "The Aegean" in Hansen and Nielsen eds., An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (Oxford 2004), 737.

- Frazee, Charles A.; Frazee, Kathleen (1988). The Island Princes of Greece: The Dukes of the Archipelago. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. pp. 52–53. ISBN 90-256-0948-1.

- Bertarelli, 161

- Clement, Anna; Hillson, Simon; Michalaki-Kollia, Maria (2008). "The ancient cemeteries of Astypalaia, Greece". Archaeology International. 12. doi:10.5334/ai.1205.

- Hillson, Simon, "The World's Largest Infant Cemetery and Its Potential for Studying Growth and Development," Hesperia Supplements Vol. 43, New Directions in the Skeletal Biology of Greece (2009), pp. 137-154.

- Astypalaia: Lady of the Aegean (Municipality of Astypalea 2011).

- Greek text at IGXII,3 173. The text appears in Robert Kenneth, "Rome and the Greek East to the death of Augustus", p. 57-58

- Fuller-Love, Heidi (19 September 2023). "My trip to a Greek island idyll where electric vehicles rule". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Groß, Andreas (13 June 2023). "Electric island Astypalea: Transformation of mobility fully underway". Volkswagen Group. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Hierocles (Byzantinus); Parthey, Gustav (1866). Hieroclis Synecdemus et notitiae graecae episcopatuum: Accedunt Nili Doxapatrii Notitia patriarchatuum et locorum nomina immutata. Nicolai. p. 123 – via Google Books.

- Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 841

Notes

- Bertarelli, L.V. (1929). Guida d'Italia, Vol. XVII. Consociazione Turistica Italiana, Milano.