Modern immigration to the United Kingdom

Since 1945, immigration to the United Kingdom, controlled by British immigration law and to an extent by British nationality law, has been significant, in particular from the Republic of Ireland and from the former British Empire, especially India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Caribbean, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Hong Kong.[2] Since the accession of the UK to the European Communities in the 1970s and the creation of the EU in the early 1990s, immigrants relocated from member states of the European Union, exercising one of the European Union's Four Freedoms. In 2021, since Brexit came into effect,[lower-alpha 1] previous EU citizenship's right to newly move to and reside in the UK on a permanent basis does not apply anymore. A smaller number have come as asylum seekers (not included in the definition of immigration) seeking protection as refugees under the United Nations 1951 Refugee Convention.

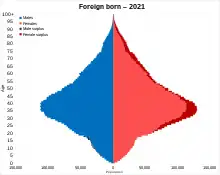

About 70% of the population increase between the 2001 and 2011 censuses was due to foreign-born immigration. 7.5 million people (11.9% of the population at the time) were born overseas, although the census gives no indication of their immigration status or intended length of stay.[4]

Provisional figures show that in 2013, 526,000 people arrived to live in the UK whilst 314,000 left, meaning that net inward migration was 212,000. The number of people immigrating to the UK increased between 2012 and 2013 by 28,000, whereas the number emigrating fell by 7,000.[5]

From April 2013 to April 2014, a total of 560,000 immigrants were estimated to have arrived in the UK, including 81,000 British citizens and 214,000 from other parts of the EU. An estimated 317,000 people left, including 131,000 British citizens and 83,000 other EU citizens. The top countries represented in terms of arrivals were: China, India, Poland, the United States, and Australia.[6]

In 2014, approximately 125,800 foreign citizens were naturalised as British citizens. This figure fell from around 208,000 in 2013, which was the highest figure recorded since 1962, when records began. Between 2009 and 2013, the average number of people granted British citizenship per year was 195,800. The main countries of previous nationality of those naturalised in 2014 were: India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Nepal, China, South Africa, Poland and Somalia.[7] The UK Government can also grant settlement to foreign nationals, which confers on them permanent residence in the UK, without granting them British citizenship. Grants of settlement are made on the basis of various factors, including employment, family formation and reunification, and asylum (including to deal with backlogs of asylum cases).[8] The total number of grants of settlement was approximately 154,700 in 2013, compared to 241,200 in 2010 and 129,800 in 2012.[7]

In comparison, migration to and from Central and Eastern Europe has increased since 2004 with the accession to the European Union of eight Central and Eastern European states, since there is free movement of labour within the EU.[9] In 2008, the UK Government began phasing in a new points-based immigration system for people from outside of the European Economic Area.

Net migration into the UK during 2022 is reported to have reached a record high of 606,000, with immigration estimated at 1.2m and emigration at 557,000. Around 114,000 people came from Ukraine and 52,000 from Hong Kong.[10]

Definitions

According to an August 2018 publication of the House of Commons Library, several definitions for a migrant exist in United Kingdom. A migrant can be:[11]

- Someone whose country of birth is different to their country of residence.

- Someone whose nationality is different to their country of residence.

- Someone who changes their country of usual residence for a period of at least a year, so that the country of destination effectively becomes the country of usual residence.

World War II

In the lead-up to World War II, many people from Germany, particularly those belonging to minorities which were persecuted under Nazi rule, such as Jews, sought to emigrate to the United Kingdom, and it is estimated that as many as 50,000 may have been successful. There were immigration caps on the number who could enter and, subsequently, some applicants were turned away. When the UK declared war on Germany, however, migration between the countries ceased.

British Empire and the Commonwealth

- British Nationality Act 1948

- Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962

- Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968

- Immigration Appeals Act 1969

- Immigration Act 1971

- British Nationality Act 1981

- Carriers Liability Act 1987

- Immigration Act 1988

- Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act 1993

- Asylum and Immigration Act 1996

- Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002

- Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006

- Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009

- Immigration Act 2014

Following the end of the Second World War, the British Nationality Act 1948 allowed the 800,000,000[12] subjects in the British Empire to live and work in the United Kingdom without needing a visa, although this was not an anticipated consequence of the Act, which "was never intended to facilitate mass migration".[13] This migration was initially encouraged to help fill gaps in the UK labour market for both skilled and unskilled jobs, including in public services such as the newly created National Health Service and London Transport. Many people were specifically brought to the UK on ships; notably the Empire Windrush in 1948.[14][15][16][17]

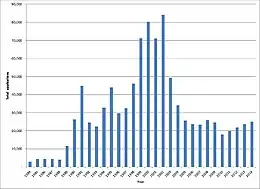

Commonwealth immigration, made up largely of economic migrants, rose from 3,000 per year in 1953 to 46,800 in 1956 and 136,400 in 1961.[12] The heavy numbers of migrants resulted in the establishment of a Cabinet committee in June 1950 to find "ways which might be adopted to check the immigration into this country of coloured people from British colonial territories".[12]

Although the Committee recommended not to introduce restrictions, the Commonwealth Immigrants Act was passed in 1962 as a response to public sentiment that the new arrivals "should return to their own countries" and that "no more of them come to this country".[18] Introducing the legislation to the House of Commons, the Conservative Home Secretary Rab Butler stated that:

The justification for the control which is included in this Bill, which I shall describe in more detail in a few moments, is that a sizeable part of the entire population of the Earth is at present legally entitled to come and stay in this already densely populated country. It amounts altogether to one-quarter of the population of the globe and at present there are no factors visible which might lead us to expect a reversal or even a modification of the immigration trend.[19]

— Rab Butler MP, 16 November 1961

The new Act required migrants to have a job before they arrived, to possess special skills or who would meet the "labour needs" of the national economy. In 1965, to combat the perceived injustice in the case where the wives of British subjects could not obtain British nationality, the British Nationality Act 1965 was adopted. Shortly afterwards, refugees from Kenya and Uganda, fearing discrimination from their own national governments, began to arrive in Britain; as they had retained their British nationality granted by the 1948 Act, they were not subject to the later controls. The Conservative MP Enoch Powell campaigned for tighter controls on immigration which resulted in the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1968.[20]

For the first time, the 1968 Act required migrants to have a "substantial connection with the United Kingdom", namely to be connected by birth or ancestry to a UK national. Those who did not could only obtain British nationality at the discretion of the national authorities.[21] One month after the adoption of the Act, Enoch Powell made his Rivers of Blood speech.[lower-alpha 2]

By 1972, with the passing of the Immigration Act, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – effectively stemming primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.[24] The Act abolished the distinction between Commonwealth and non-Commonwealth entrants. The Conservative government nevertheless allowed, amid much controversy, the immigration of 27,000 individuals displaced from Uganda after the coup d'état led by Idi Amin in 1971.[20]

In the 1970s, an average of 72,000 immigrants were settling in the UK every year from the Commonwealth; this decreased in the 1980s and early-1990s to around 54,000 per year, only to rise again to around 97,000 by 1999. The total number of Commonwealth immigrants since 1962 is estimated at 2,500,000.

The Ireland Act 1949 has the unusual status of recognising the Republic of Ireland, but affirming that its citizens are not citizens of a foreign country for the purposes of any law in the United Kingdom.[25] This act was initiated at a time when Ireland withdrew from the Commonwealth of Nations after declaring itself a republic.[26]

Post-war immigration (1945–1983)

Following the end of the Second World War, substantial groups of people from Soviet-controlled territories settled in the UK, particularly Poles and Ukrainians. The UK recruited displaced people as so-called European Volunteer Workers in order to provide labour to industries that were required in order to aid economic recovery after the war.[27] In the 1951 United Kingdom census, the Polish-born population of the country numbered some 162,339, up from 44,642 in 1931.[28][29]

Indians began arriving in the UK in large numbers shortly after their country gained independence in 1947, although there were a number of people from India living in the UK even in the earlier years. More than 60,000 arrived before 1955, many of whom drove buses, or worked in foundries or textile factories. The flow of Indian immigrants peaked between 1965 and 1972, boosted in particular by Ugandan dictator Idi Amin's sudden decision to expel all 50,000 Gujarati Indians from Uganda. Around 30,000 Ugandan Asians emigrated to the UK.[30]

Following the independence of Pakistan, Pakistani immigration to the United Kingdom increased, especially during the 1950s and 1960s. Many Pakistanis came to Britain following the turmoil during the partition of India and the subsequent independence of Pakistan; among them were those who migrated to Pakistan upon displacement from India, and then emigrated to the UK, thus becoming secondary migrants.[31] Migration was made easier as Pakistan was a member of the Commonwealth of Nations.[32] Pakistanis were invited by employers to fill labour shortages which arose after the Second World War. As Commonwealth citizens, they were eligible for most British civic rights. They found employment in the textile industries of Lancashire and Yorkshire, manufacturing in the West Midlands, and car production and food processing industries of Luton and Slough. It was common for Pakistani employees to work nightshifts and at other less-desirable hours.[33]

In addition, there was a stream of migrants from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).[34][35] During the 1970s, a large number of East African-Asians, most of whom already held British passports because they had been British subjects settled in the overseas colonies, entered the United Kingdom from Kenya and Uganda, particularly as a result of the expulsion of Asians from Uganda by Idi Amin in 1972.

There was also an influx of refugees from Hungary, following the crushing of the 1956 Hungarian revolution, numbering 20,990 people.[36]

Until the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, all Commonwealth citizens could enter and stay in the UK without any restriction. The Act made Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKCs), whose passports were not directly issued by the UK Government (i.e., passports issued by the Governor of a colony or by the Commander of a British protectorate), subject to immigration control.

Enoch Powell gave the famous "Rivers of Blood" speech on 20 April 1968 in which he warned his audience of what he believed would be the consequences of continued unchecked immigration from the Commonwealth to Britain. Conservative Party leader Edward Heath fired Powell from his Shadow Cabinet the day after the speech, and he never held another senior political post. Powell received 110,000 letters – only 2,300 disapproving.[37] Three days after the speech, on 23 April, as the Race Relations Bill was being debated in the House of Commons, around 2,000 dockers walked off the job to march on Westminster protesting against Powell's dismissal,[38] and the next day 400 meat porters from Smithfield market handed in a 92-page petition in support of Powell.[39] At that time, 43% of junior doctors working in NHS hospitals, and some 30% of student nurses, were immigrants, without which the health service would needed to have been curtailed.[37]

By 1972, only holders of work permits, or people with parents or grandparents born in the UK could gain entry – significantly reducing primary immigration from Commonwealth countries.[24]

Immigration as influenced by the EU (1983–2022)

The British Nationality Act 1981, which was enacted in 1983, distinguishes between British citizens and British Overseas Territories citizens. It also made a distinction between nationality by descent and nationality other than by descent. Citizens by descent cannot automatically pass on British nationality to a child born outside the United Kingdom or its Overseas Territories (though in some situations the child can be registered as a citizen).

Immigration officers have to be satisfied with a person's nationality and identity and entry can be refused if they are not satisfied.[40]

During the 1980s and 1990s, the civil war in Somalia led to a large number of Somali immigrants, comprising the majority of the current Somali population in the UK. In the late-1980s, most of these early migrants were granted asylum, while those arriving later in the 1990s more often obtained temporary status. There has also been some secondary migration of Somalis to the UK from the Netherlands and Denmark. The main driving forces behind this secondary migration included a desire to reunite with family and friends and for better employment opportunities.[41]

Non-European immigration rose significantly during the period from 1997, not least because of the government's abolition of the primary purpose rule in June 1997.[42] This change made it easier for UK residents to bring foreign spouses into the country. The former government adviser Andrew Neather in the Evening Standard stated that the deliberate policy of ministers from late-2000 until early-2008 was to open up the UK to mass migration.[43][44]

The Immigration Rules, under the Immigration Act 1971, were updated in 2012 (Appendix FM) to create a strict minimum income threshold for non-EU spouses and children to be given leave to remain in the UK. These rules were challenged in the courts, and in 2017 the Supreme Court found that while "the minimum income threshold is accepted in principle" they decided that the rules and guidance were defective and unlawful until amended to give more weight to the interests of the children involved, and that sources of funding other than the British spouse's income should be considered.[45][46]

The foreign-born population increased from about 5.3 million in 2004 to nearly 9.3 million in 2018. In the decade leading up to 2018, the number of non-EU migrants outnumbered EU migrants while the number of EU migrants increased more rapidly. EU migrants were noted to be less likely to become British citizens than non-EU migrants.[1]

In January 2021, analysis by the Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence suggested that there had been an "unprecedented exodus" of almost 1.3 million foreign-born people from the UK between July 2019 and September 2020, in part due to the burden of job losses resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic falling disproportionately on foreign-born workers. Interviews conducted by Al Jazeera suggested that Brexit may have been a more significant push factor than the pandemic.[47] Subsequent analysis of the impact of the pandemic on population statistics generated by the Labour Force Survey (LFS) suggests that "LFS-based estimates are likely to significantly overstate the change in the non-UK national population". Payroll data shows that the number of EU workers fell by 7 per cent between October–December 2019 and October–December 2020.[48]

Office for National Statistics migration estimates published in November 2021 suggest that the number of EU nationals leaving the UK exceeded the number arriving by around 94,000, compared to net inward migration from the EU to the UK of 32,000 in 2019. Some commentators suggested that these figures underestimate the extent of emigration of EU nationals from the UK.[49]

Immigrants from the European Union

One of the Four Freedoms of the European Union, of which the United Kingdom is a former member, is the right to the free movement of workers as codified in the Directive 2004/38/EC and the EEA Regulations (UK).

With the expansion of the EU on 1 May 2004, the UK has accepted immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe, Malta and Cyprus, although the substantial Maltese and Greek-Cypriots and Turkish-Cypriot communities were established earlier through their Commonwealth connection. There are restrictions on the benefits that members of eight of these accession countries ('A8' nationals) can claim, which are covered by the Worker Registration Scheme.[50] Many other European Union member states exercised their right to temporary immigration control (which ended in 2011)[51] over entrants from these accession states,[52] but some subsequently removed these restrictions ahead of the 2011 deadline.[53]

The United Kingdom uses statistics to predict migration that are produced primarily from the International Passenger Survey conducted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The survey's primary mission is to help government's understand the effects of tourism and travel on their economy. Two parliamentary committees criticized the survey and found it to lack credibility. The actual net migration in 2015-16 from EU states to the United Kingdom, 29,000, was 16% higher than the ONS expected.[54]

Research conducted by the Migration Policy Institute for the Equality and Human Rights Commission suggests that, between May 2004 and September 2009, 1.5 million workers migrated from the new EU member states to the UK, but that many have returned home, with the result that the number of nationals of the new member states in the UK increased by some 700,000 over the same period.[55][56] Migration from Poland in particular has become temporary and circular in nature.[57] In 2009, for the first time since the enlargement, more nationals of the eight Central and Eastern European states that joined the EU in 2004 left the UK than arrived.[58] Research commissioned by the Regeneration and Economic Development Analysis Expert Panel suggested migrant workers leaving the UK due to the recession are likely to return in the future and cited evidence of "strong links between initial temporary migration and intended permanent migration".[59]

The Government announced that the same rules would not apply to nationals of Romania and Bulgaria (A2 nationals) when those countries acceded to the EU in 2007. Instead, restrictions were put in place to limit migration to students, the self-employed, highly skilled migrants and food and agricultural workers.[60]

In February 2011, the Leader of the Labour Party, Ed Miliband, stated that he thought that the Labour government's decision to permit the unlimited immigration of eastern European migrants had been a mistake, arguing that they had underestimated the potential number of migrants and that the scale of migration had had a negative impact on wages.[61][62]

A report by the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) entitled International Migration and Rural Economies, suggests that intra-EU migration since enlargement has resulted in migrants settling in rural locations without a prior history of immigration.[63]

Research published by University College London in July 2009 found that, on average, A8 migrants were younger and better educated than the native population, and that if they had the same demographic characteristics of natives, would be 13 per cent less likely to claim benefits and 28 per cent less likely to live in social housing.[64][65]

Expulsions of criminals

Expulsions of immigrants who had committed crimes varied between 4,000 and 5,000 a year between 2007 and 2010.[66][67]

Controversy over application of section 322(5)

In May 2018 under the tenure of Sajid Javid, it was the view of a significant minority that the Home Office was misusing section 322(5) of the Immigration Rules.[68][69] The section was designed to combat terrorism, but the Home Office had been wrongly applying it to hundreds of settled, highly skilled workers.[68][70][71][72] The hardship faced by the workers was compared to the Windrush scandal, which occurred around the same time.[68][73][74][72] By early 2019, approximately 90 people had been deported from the UK due to section 322(5).[75]

In May 2021, the Director of Advocacy at the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei wrote an opinion piece for The Guardian highlighting how the Home Office under Priti Patel viewed “activists as a security threat”. The human rights activist was tortured and imprisoned in Bahrain for taking part in the country's Arab Spring uprisings, following which he fled to the United Kingdom. In 2015, Bahrain “arbitrarily revoked” his citizenship. Before the birth of his daughter, Alwadaei submitted his application for indefinite leave to stay in the UK and to prevent his child from being born stateless. However, the Home Office delayed the approval of his application until 2019, and his daughter was born without any citizenship. Alwadaei said the Home Office was keeping a record of his years of activism, labeling his case as “complex”. His daughter was not granted the British citizenship she was entitled to by law, even after her parents forcefully paid £1,012 for her citizenship application. Alwadaei also pointed to the growing ties of Patel with conservation regime, Bahrain, stating that it is "deeply alarming”.[76]

Immigration Rules and prior statutory instruments and controls on aliens

In 1914, Parliament enacted "panic legislation", The Alien Restrictions Act, 1914,[77] during the onset of World War I to place limits on the entry into, and stay in, the UK of foreign nationals.[78] The act provided for the introduction of Orders in Council to detail the restrictions to be imposed on aliens.[77] In 1919, after the conclusion of the war, that legislation was re-enacted,[79] while the provisions that limited it to a time of war were removed.[78] By the early 1950s, roughly 20 Orders in Council had been passed to flesh out the details for immigration control.[78]

In 1952, Parliament moved to place its imprimatur on those orders by approving a consolidating order, The Aliens Order, 1953,[80] that also removed some of the more objectionable provisions.[78] However, other provisions of concern remained, including those potentially incompatible with other laws and international obligations of the UK.[78]

The Immigration Act 1971, section 1, provided for "rules laid down by the Secretary of State as to the practice to be followed in the administration of this Act".[81]

In 1972, the Heath administration introduced the first proposed Immigration Rules under the 1971 act.[82] The rules proposal drew criticism from Conservative Party backbenchers, because it formally implemented a limit of six months of leave to enter as a visitor for white "Old Commonwealth" citizens who were "non-patrial" (did not have Right of Abode under the 1971 act, generally because they did not have a parent or grandparent from the UK).[82] At the same time the proposal opened the door to free movement of certain European workers from European Economic Community member states.[82] Seven backbenchers voted against the proposed Rules and 53 abstained, leading to defeat.[82] Minutes from a Cabinet meeting the next day conclude that "anti-European sentiment" among backbenchers, who instead preferred "Old Commonwealth" migration to the UK, was at the core of the result.[82] The proposal was revised, and the first Rules were passed in January 1973.[82]

By August 2018, the Immigration Rules stood at almost 375,000 words, often so precise and detailed that the service of a lawyer are typically required to navigate them.[83] That length represented nearly a doubling in just a decade.[83] During the period of the introduction of the "hostile environment" policy under Prime Minister Theresa May, more than 1,300 changes were made to the Rules in 2012 alone.[83] Former Lord Justice of Appeal Stephen Irwin referred to the complexity of the system as "something of a disgrace", and an effort to gradually overhaul the Rules into a more understandable system began to take place.[83] The England and Wales Law Commission began to make recommendations for clearer rules to be adopted.[83]

Managed migration

"Managed migration" is the term for all legal labour and student migration from outside of the European Union and this accounts for a substantial percentage of overall immigration figures for the UK. Many of the immigrants who arrive under these schemes bring skills which are in short supply in the UK. This area of immigration is managed by UK Visas and Immigration, a department within the Home Office. Applications are made at UK embassies or consulates or directly to UK Visas and Immigration, depending upon the type of visa or permit required.

In April 2006, changes to the managed migration system were proposed that would create one points-based immigration system for the UK in place of all other schemes. Tier 1 in the new system – which replaced the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme – gives points for age, education, earning, previous UK experience but not for work experience. The points-based system was phased in over the course of 2008, replacing previous managed migration schemes such as the work permit system and the Highly Skilled Migrant Programme.[85][86]

A points-based system is composed of five tiers was first described by the UK Border Agency as follows:

- Tier 1 – for highly skilled individuals, who can contribute to growth and productivity;

- Tier 2 – for skilled workers with a job offer, to fill gaps in the United Kingdom workforce;

- Tier 3 – for limited numbers of low-skilled workers needed to fill temporary labour shortages;

- Tier 4 – for students;

- Tier 5 – for temporary workers and young people covered by the Youth Mobility Scheme, who are allowed to work in the United Kingdom for a limited time to satisfy primarily non-economic objectives.[87]

The Migration Advisory Committee was established in 2007 to give policy advice.

In June 2010, The newly elected Coalition government brought in a temporary cap on immigration of those entering the UK from outside the EU, with the limit set as 24,100, in order to stop an expected rush of applications before a permanent cap was imposed in April 2011.[88] The cap caused tension within the coalition, and then-Business Secretary Vince Cable argued that it was harming British businesses.[89] Others have argued that the cap would have a negative impact on Britain's status as a centre for scientific research.[90]

For family relatives of European Economic Area nationals living in the UK, there is the EEA family permit which enables those family members to join their relatives already living and working in the UK.

Though immigration is a matter that is reserved to the UK Government under the legislation that established devolution for Scotland in 1999, the Scottish Government was able to get an agreement from the Home Office for their Fresh Talent Initiative which was designed to encourage foreign graduates of Scottish universities to stay in Scotland to look for employment.[91] The Fresh Talent Initiative ended in 2008, following the introduction of points-based system.[92][93]

Refugees and asylum seekers

The UK is a signatory to the UN 1951 Refugee Convention as well as the 1967 Protocol and has therefore a responsibility to offer protection to people who seek asylum and fall into the legal definition of a "refugee", and moreover not to return (or refoule) any displaced person to places where they would otherwise face persecution. Cuts to legal aid prevent asylum seekers getting good advice or arguing their case effectively. This can mean refugees being returned to a country where they face certain death.[95]

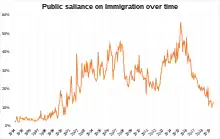

The issue of immigration has been a controversial political issue since the late 1990s. Both the Labour Party and the Conservatives have suggested policies perceived as being "tough on asylum"[96] (although the Conservatives have dropped a previous pledge to limit the number of people who could claim asylum in the UK, which would likely have breached the UN Refugee Convention)[97] and the tabloid media frequently print headlines about an "immigration crisis".[98]

This is denounced, by those seeking to ensure that the UK upholds its international obligations, as disproportionate. Concern is also raised about the treatment of those held in detention and the practice of dawn raiding families, and holding young children in immigration detention centres for long periods of time.[99][100] The policy of detaining asylum-seeking children was to be abandoned as part of the coalition agreement between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, who formed a government in May 2010.[101] However, in July 2010 the government was accused of back-tracking on this promise after the Immigration Minister Damian Green announced that the plan was to minimise, rather than end, child detention.[102]

However, critics of the UK's asylum policy often point out the "safe third country rule" – the convention that asylum seekers must apply in the first free nation they reach, not go "asylum shopping" for the nation they prefer. EU courts have upheld this policy.[103] Research conducted by the Refugee Council suggests that most asylum seekers in the UK had their destination chosen for them by external parties or agents, rather than choosing the UK themselves.[104]

In February 2003, Prime Minister Tony Blair promised on television to reduce the number of asylum seekers by half within 7 months,[105] apparently catching unawares the members of his own government with responsibility for immigration policy. David Blunkett, then the Home Secretary, called the promise an objective rather than a target.[106]

It was met according to official figures.[107] There is also a Public Performance Target to remove more asylum seekers who have been judged not to be refugees under the international definition than new anticipated unfounded applications. This target was met early in 2006.[108] Official figures for numbers of people claiming asylum in the UK were at a 13-year low by March 2006.[109]

Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International have argued that the government's new policies, particularly those concerning detention centres, have detrimental effects on asylum applicants[110] and their children,[111] and those facilities have seen a number of hunger strikes and suicides. Others have argued that recent government policies aimed at reducing 'bogus' asylum claims have had detrimental impacts on those genuinely in need of protection.[112]

The UK hosts one of the largest populations of Iraqi refugees outside the Gulf region. About 65-70% of people originating from Iraq are Kurdish, and 70% of those from Turkey and 15% of those from Iran are Kurds.[113]

Asylum seekers have been kept in detention after the courts ordered their release because the Home Office maintains detention is not dissimilar to emergency accommodation. Immigrants with the right to stay in the UK are denied housing and cannot be released. In other cases vulnerable asylum seekers are released onto the streets with nowhere to live. In January 2018 the government repealed a law that previously allowed homeless detainees to apply for housing while in detention if they had nowhere to live when released. Charities maintain around 2,000 detainees who before this applied for support each year can no longer do so.[114]

On 9 August 2020, the reports suggested that the number of people who reached the United Kingdom shores in small boats, during that year, surpassed 4,000. The undocumented migrant crossings of the English Channel mounted tensions between the UK and France.[115]

On 17 August 2021, the United Kingdom Government launched a new resettlement programme which aims to settle 20,000 Afghan refugees fleeing the 2021 Taliban offensive over a five–year period in the UK.[116][117] This includes many Afghans who worked with British forces in Afghanistan.[118] That same year the government also launched a scheme for Hongkongers following the Hong Kong national security law, with an estimated thousands emigrating to the UK either as refugees, asylum seekers or under student visas.[119]

As of May 2023, the United Kingdom has issued 230,300 visas to Ukrainians as a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine from a total of 292,900 applications received.[120]

The UK also operates the UK Resettlement Scheme, Community Sponsorship Scheme and Mandate Resettlement Scheme.[121] Previous UK resettlement schemes included the Gateway Protection Programme and the Syrian Vulnerable Person Resettlement Programme.[122][123]

Illegal immigration

Illegal immigrants in the UK include those who have:

- entered the UK without authority

- entered with false documents

- overstayed their visas

Although it is difficult to know how many people reside in the UK illegally, a Home Office study released in March 2005 estimated a population of between 310,000 and 570,000.[124]

A recent study into irregular immigration states that "most irregular migrants have committed administrative offences rather than a serious crime".[125]

Jack Dromey, Deputy General of the Transport and General Workers Union and Labour Party treasurer, suggested in May 2006 that there could be around 500,000 illegal workers. He called for a public debate on whether an amnesty should be considered.[126] David Blunkett has suggested that this might be done once the identity card scheme is rolled out.[127]

London Citizens, a coalition of community organisations, is running a regularisation campaign called Strangers into Citizens, backed by figures including the former leader of the Catholic Church in England and Wales, the Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor.[128] Analysis by the Institute for Public Policy Research suggested that an amnesty could net the government up to £1.038 billion per year in fiscal revenue, however the long term implications of such a measure are uncertain.[129]

It has since been suggested that to deport all of the illegal immigrants from the UK might take 20 years and cost up to £12 billion.[130] Former Mayor of London Boris Johnson commissioned a study into a possible amnesty for illegal immigrants, citing larger tax gains within the London area which is considered to be home to the majority of the country's population of such immigrants.[131]

In February 2008, the government introduced new £10,000 fines for employers found to be employing illegal immigrants where there is negligence on the part of the employer, with unlimited fines or jail sentences for employers acting knowingly.[132]

Women who are illegal immigrants and also domestic violence victims risk deportation and are deported if they complain about violence. Women get brought illegally into the UK by men intending to abuse them. Women are sometimes deterred from complaining about violence to them due to the risk of deportation, therefore perpetrators including rapists remain at large.[133] Martha Spurrier of Liberty said, "It will leave people afraid to report crime, robbing them of protection under the law and creating impunity for criminals who target vulnerable people with unsettled immigration status. This is criminalising victims and letting criminals off the hook."[134]

Comparison of European Union countries

According to Eurostat, 47.3 million people lived in the European Union in 2010 who were born outside their resident country. This corresponds to 9.4% of the total EU population. Of these, 31.4 million (63%) were born outside the EU and 16.0 million (32%) were born in another EU member state. The largest absolute numbers of people born outside the EU were in Germany (6.4 million), France (5.1 million), the United Kingdom (4.7 million), Spain (4.1 million), Italy (3.2 million), and the Netherlands (1.4 million).[135]

| Country | Population density per square mile | Total population (1000) | Total foreign-born (1000) | % | Born in other EU state (1000) | % | Born in a non-EU state (1000) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EU 27 | 188 | 501,098 | 47,348 | 9.4 | 15,980 | 3.2 | 31,368 | 6.3 |

| Netherlands | 1,052 | 16,575 | 1,832 | 11.1 | 428 | 2.6 | 1,404 | 8.5 |

| Belgium (2007) | 942 | 10,666 | 1,380 | 12.9 | 695 | 6.5 | 685 | 6.4 |

| United Kingdom | 662 | 62,008 | 7,012 | 11.3 | 2,245 | 3.6 | 4,767 | 7.7 |

| Germany | 583 | 81,802 | 9,812 | 12.0 | 3,396 | 4.2 | 6,415 | 7.8 |

| Italy | 522 | 60,340 | 4,798 | 8.0 | 1,592 | 2.6 | 3,205 | 5.3 |

| Denmark | 339 | 5,534 | 500 | 9.0 | 152 | 2.8 | 348 | 6.3 |

| France | 301 | 64,716 | 7,196 | 11.1 | 2,118 | 3.3 | 5,078 | 7.8 |

| Portugal | 298 | 10,637 | 793 | 7.5 | 191 | 1.8 | 602 | 5.7 |

| Austria | 263 | 8,367 | 1,276 | 15.2 | 512 | 6.1 | 764 | 9.1 |

| Spain | 240 | 45,989 | 6,422 | 14.0 | 2,328 | 5.1 | 4,094 | 8.9 |

| Greece | 212 | 11,305 | 1,256 | 11.1 | 315 | 2.8 | 940 | 8.3 |

| Sweden | 57 | 9,340 | 1,337 | 14.3 | 477 | 5.1 | 859 | 9.2 |

Citizenship laws

Individuals wanting to apply for British citizenship have to demonstrate their commitment by learning English, Welsh or Scottish Gaelic and by having an understanding of British history, culture and traditions.[136] Any individual seeking to apply for naturalisation or indefinite leave to remain must pass the official Life in the UK test.[137]

Brexit

Figures published in November 2021 by the Office for National Statistics showed that more EU nationals left the UK in 2020 than arrived for the first time since 1991, a net emigration of around 94,000. ... At first sight, the UK now has one of the most liberal immigration systems in the world outside the EU.[138]

See also

- British diaspora

- British nationality law

- Calais jungle

- Foreign-born population of the United Kingdom

- Immigrant benefits urban legend, a hoax regarding benefits comparison

- Immigration to Europe

- MigrationWatch UK

- Surinder Singh route

- Visa policy of the United Kingdom

- List of countries by British immigrants

- List of countries by foreign-born population

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories by fertility rate

- List of renewable resources produced and traded by the United Kingdom

- UK immigration enforcement

- Auf Wiedersehen, Pet, a TV sitcom about British economic migrants, during the early 1980s recession in the UK

Notes

- The Brexit came into force by the end of the transition period provisionally from 1 January 2021, and formally into force on 1 May 2021 after completion of the ratification processes by both parties (the EU and the UK).[3]

- The Act received Royal Assent on 1 March;[22] the speech was delivered on 20 April.[23]

References

- "Migrants in the UK: An Overview". Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- Randall Hansen (2000). Citizenship and Immigration in Postwar Britain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191583018.

- "EU-UK trade and cooperation agreement: Council adopts decision on conclusion". www.consilium.europa.eu. 29 April 2021.

- "Immigration Patterns of Non-UK Born Populations in England and Wales in 2011" (PDF). Office for National Statistics. 17 December 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- "Migration Statistics Quarterly Report, May 201". Office for National Statistics. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- "BBC News – Immigration points-based systems compared". BBC News. June 2016.

- Blinder, Scott (27 March 2015). "Naturalisation as a British Citizen: Concepts and Trends" (PDF). The Migration Observatory, University of Oxford. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- Blinder, Scott (11 June 2014). "Settlement in the UK". The Migration Observatory, University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- See Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- "UK net migration hits record high of 606,000". BBC News. BBC. 25 May 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- "Migration Statistics - Commons Library briefing - UK Parliament". Researchbriefings.parliament.uk. 24 August 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Immigration (Hansard, 19 March 2003)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 19 March 2003.

- Hansen, Randall (2000). Citizenship and Immigration in Post-war Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780199240548.

- "Windrush settlers". The National Archives. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Glennie, Alex; Chappell, Laura (16 June 2010). "Jamaica: From Diverse Beginning to Diaspora in the Developed World". Migration Information Source. Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Snow, Stephanie; Jones, Emma (8 March 2011). "Immigration and the National Health Service: putting history to the forefront". Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Cavendish, Richard (6 June 1998). "Arrival of SS Empire Windrush". History Today. 48 (6). Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Immigrants to United Kingdom (Hansard, 9 February 1965)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 9 February 1965.

- "COMMONWEALTH IMMIGRANTS BILL (Hansard, 16 November 1961)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 16 November 1961.

- Archives, The National. "Commonwealth Immigration control and legislation". www.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- "COMMONWEALTH IMMIGRANTS BILL (Hansard, 29 February 1968)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 29 February 1968.

- "Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968" (PDF). legislation.gov.uk.

- "Enoch Powell's Rivers of Blood: The speech that divided a nation". Sky News. 24 April 2018.

- Brah, Avtar (1996). Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. London: Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-12126-2.

- "Ireland Act 1949". Office of Public Sector Information. 2 June 1949. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- Layton-Henry, Zig (2001). "Patterns of privilege: Citizenship rights in Britain". In Kondo, Atsushi (ed.). Citizenship in a Global World: Comparing Citizenship Rights for Aliens. Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 116–135. ISBN 0-333-80265-9.

- Kay, Diana; Miles, Robert (1998). "Refugees or migrant workers? The case of the European Volunteer Workers in Britain (1946–1951)". Journal of Refugee Studies. 1 (3–4): 214–236. doi:10.1093/jrs/1.3-4.214.

- Colin Holmes (1988) John Bull's Island: Immigration and British Society 1871–1971, Basingstoke: Macmillan

- Kathy Burrell (2002) Migrant memories, migrant lives: Polish national identity in Leicester since 1945, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society 76, pp. 59–77

- "1972: Asians given 90 days to leave Uganda". BBC On This Day. 7 August 1972. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "The Pakistani Community". BBC. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Satter, Raphael G. (13 May 2008). "Pakistan rejoins Commonwealth – World Politics, World". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Robin Richardson; Angela Wood. "The Achievement of British Pakistani Learners" (PDF). Trentham Books. pp. 2, 1–17.

- Ember, Melvin; Ember, Carol R.; Skoggard, Ian (2005). Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities, Volume 1. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780306483219.

- Fox, Susan (2015). The New Cockney: New Ethnicities and Adolescent Speech in the Traditional East End of London. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137503992.

- UNHCR (2006) 'A matter of the heart': How the Hungarian crisis changed the world of refugees, Refugees 114(3), pp. 4–11

- "British Conservative Sees Foreign Influx as Threat". Eugene Register-Guard. 22 December 1968. p. 4A.

- ""We back Enoch" march by dockers; He is being victimised, they say", Evening Times, p. 1, 23 April 1968

- "More Call For Britain To Shut Out Nonwhites". Schenectady Gazette. 25 April 1968. p. 1.

- Immigration staff can ask Muslim women to remove veils Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine 24dash.com, 26 October 2006

- "Post-Conflict Identities: Practices and Affiliations of Somali Refugee Children – Briefing Notes" (PDF). The University of Sheffield. August 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- "BBC Politics 97". www.bbc.co.uk.

- Neather, Andrew (23 October 2009). "Don't listen to the whingers – London needs immigrants". Evening Standard. London. Archived from the original on 2 December 2009. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Whitehead, Tom (23 October 2009). "Labour wanted mass immigration to make UK more multicultural, says former adviser". Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- Travis, Alan (22 February 2017). "Supreme court backs minimum income rule for non-European spouses". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- The impact on children of the Family Migration Rules (PDF) (Report). Children's Commissioner for England. August 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Child, David (15 January 2021). "'Unprecedented exodus': Why are migrant workers leaving the UK?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Freeman, David (23 March 2021). "Coronavirus and the impact on payroll employment: experimental analysis". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Romei, Valentina (25 November 2021). "Net migration of EU nationals to UK turned negative in 2020". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- The Worker Registration Scheme Archived 2 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine Home Office

- Freedom of movement for workers after enlargement Archived 18 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine Europa

- Barriers still exist in larger EU, BBC News, 1 May 2005

- EU free movement of labour map, BBC News, 4 January 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007

- "EU migration to UK 'underestimated'". 21 August 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Sumption, Madeleine; Somerville, Will (January 2010). The UK's new Europeans: Progress and challenges five years after accession (PDF). p. 13. ISBN 978-1-84206-252-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Doward, Jamie; Rogers, Sam (17 January 2010). "Young, self-reliant, educated: portrait of UK's eastern European migrants". The Observer. London. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- "Migrants to UK 'returning home'". BBC News. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- "UK sees shift in migration trend". BBC News. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Anne E. Green (March 2011). "Impact of Economic Downturn and Immigration" (PDF). Institute for Employment Research, University of Warwick. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Reid outlines new EU work curbs, BBC News, 24 October 2006. Retrieved 24 October 2006.

- "Labour accused of covering up warnings about immigration". The Daily Telegraph. 1 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- "Video: Miliband – 'Immigration hit wages'". The Independent. 28 February 2011. Archived from the original on 15 May 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Experian Plc (March 2011). "International Migration and Rural Economies" (PDF). Department for Communities and Local Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- Dustmann, Christian; Frattini, Tommaso; Halls, Caroline (July 2009). "Assessing the fiscal costs and benefits of A8 migration to the UK" (PDF). CReAM Discussion Paper. Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration, Department of Economics, University College London. Retrieved 8 November 2009.

- Doyle, Jack (24 July 2009). "EU migrants 'good for UK economy'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Alleyne, Richard (19 July 2012). "A fifth of murder and rape suspects are immigrants". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- "Foreign criminals deported 'at earliest opportunity'". BBC News. 18 December 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Hill, Amelia (6 May 2018). "At least 1,000 highly skilled migrants wrongly face deportation, experts reveal". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- "Parliament set to debate the controversy over paragraph 322(5) of the Immigration Rules - www.ein.org.uk". www.ein.org.uk.

- Hill, Amelia (6 May 2018). "'Credible and honest': the company director facing deportation to Pakistan". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- Wilding, Jo (16 May 2018). "Paragraph 322(5): what the Home Office uses to refuse highly skilled migrants leave to remain in Britain". The Conversation.

- Hill, Amelia (23 November 2018). "Home Office 'wrongly tried to deport 300 skilled migrants'". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- March, Polly (21 June 2018). "Family in immigration row £15k in debt". BBC.

- "30,000 sign petition in support of Indian professionals denied UK visas". The Economic Times. 17 May 2018.

- Hill, Amelia (2 February 2019). "Home Office 'wrecked my life' with misuse of immigration law". Guardian News & Media Limited.

- "Bahrain made me stateless, now my young daughter is facing a similar fate in the UK". The Guardian. 20 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Aliens Restriction Act, 1914", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 5 August 1914, 1914 c. 12, retrieved 6 October 2022

- HC Deb, 20 November 1956 vol 560 cc1611-54

- "Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act, 1919", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 23 December 1919, 1919 c. 12, retrieved 6 October 2022

- Statutory Instruments 1953. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1954. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- "Immigration Act 1971: Section 1", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 28 October 1971, 1971 c. 77 (s. 1), retrieved 6 October 2022

- Partos, Rebecca (2019). The Making of the Conservative Party's Immigration Policy (electronic ed.). Routledge. pp. PT81–PT82. ISBN 9781351010634.

- Bozic, Martha; Barr, Caelainn; McIntyre, Niamh (27 August 2018). "Revealed: immigration rules in UK more than double in length". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Migration Statistics Quarterly Report, August 2014". Office for National Statistics. 28 August 2014.

- "The points-based system". Border & Immigration Agency. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- "Timetable for PBS launch". Border & Immigration Agency. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- "How the points-based system works". UK Border Agency. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- Boxell, James (28 June 2010). "Tories begin consultation on cap for migrants". The Financial Times. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- "Vince Cable: Migrant cap is hurting economy". The Guardian. Press Association. 17 September 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- "Nobel laureates urge rethink over immigration cap". The Guardian. Press Association. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- New Scots: Attracting Fresh Talent to meet the Challenge of Growth scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2008

- "Fresh Talent: Working in Scotland". UK Border Agency. Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- "Browse: Work in the UK - GOV.UK". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Table as_01: Asylum applications and initial decisions for main applicants, by country of nationality". Home Office. 27 August 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Lack of legal aid puts asylum seekers' lives at risk, charity warns The Guardian, 19 July 2018

- Tom Bentley Please, not again! openDemocracy, 11 February 2005

- Q&A: Conservatives and Immigration, BBC News, 9 November 2006. Retrieved 13 December 2007

- Roy Greenslade Seeking scapegoats: The coverage of asylum in the UK press (PDF) Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Institute for Public Policy Research, May 2005

- "Nicol Stephen condemns dawn raids". BBC News. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Migrant children held 'too long' in detention, MPs say". BBC News. 29 November 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- "Detention of asylum-seeker children to be scrapped". The Times. London. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- McVeigh, Karen; Taylor, Matthew (9 September 2010). "Government climbdown on detention of children in immigration centres". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- First Aid for asylum seekers Asylumlaw.org

- Travis, Alan (14 January 2010). "Chance brings refugees to Britain not choice, says report". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- Blair's asylum gamble BBC News 7 February 2003

- Ministers back down on asylum pledge BBC News 10 February 2003

- Blair's asylum target met BBC News 27 November 2003

- Public performance target: removing more failed asylum seekers than new anticipated unfounded applications Archived 29 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine Home Office

- UK asylum claims at '13-year low' BBC News 17 March 2006

- Seeking asylum is not a crime: Detention of people who have sought asylum (PDF) Amnesty International, 20 June 2005

- McVeigh, Karen (31 August 2009). "Ministers under fire for locking up immigrant children". The Guardian. London. p. 1. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Cooley, Laurence; Rutter, Jill (2007). "Turned away? Towards better protection for refugees fleeing violent conflict". Public Policy Research. 14 (3): 176–180. doi:10.1111/j.1744-540X.2007.00485.x.

- Begikhani, Nazand; Gill, Aisha; Hague, Gill; Ibraheem, Kawther (November 2010). "Final Report: Honour-based Violence (HBV) and Honour-based Killings in Iraqi Kurdistan and in the Kurdish Diaspora in the UK" (PDF). Centre for Gender and Violence Research, University of Bristol and Roehampton University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Bulman, Mary (27 May 2018). "Asylum seekers unlawfully held in removal centres for months despite courts ruling they can be released, lawyers warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "More than 4,000 have crossed Channel to UK in small boats this year". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Walker, Peter (17 August 2021). "How is UK planning to help resettle Afghan refugees?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "UK announces plan to resettle 20,000 refugees from Afghanistan". Al Jazeera. 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- Association, Press (31 May 2021). "More Afghans who worked for British forces to resettle in UK". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- "Supporting Hong Kong arrivals to the UK | Local Government Association". www.local.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- "Ukraine Family Scheme, Ukraine Sponsorship Scheme (Homes for Ukraine) and Ukraine Extension Scheme visa data". gov.uk. Home Office. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- "UK Refugee Resettlement: Policy Guidance" (PDF). Home Office. August 2021. p. 3. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Vulnerable Persons and Vulnerable Children's Resettlement Schemes Factsheet, March 2021". UK Visas and Immigration. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- "Policy and legislative changes affecting migration to the UK: timeline". Home Office. 26 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- The thorny issue of illegal migrants BBC News, 17 May 2006.

- Irregular migration in the UK: An ippr factfile Institute for Public Policy Research, April 2006, p. 5.

- Amnesty call over illegal workers BBC News, 20 May 2006.

- Blunkett: Immigration amnesty on cards epolitix.com, 14 June 2006

- Joe Boyle, Migrants find a voice in the rain, BBC News, 7 May 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2007

- "Jacqui Smith should back amnesty for illegal workers". Institute for Public Policy Research. 15 July 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Tighter immigration controls could enable an amnesty for illegal immigrants say IPPR". Institute for Public Policy Research. 3 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- "Johnson ponders immigrant amnesty". BBC News. 22 November 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- Richard Ford (29 February 2008). "£10,000 fines for employing illegal migrant without check". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- Jeraj, Catrin Nye, Natalie Bloomer and Samir (14 May 2018). "Victims of serious crime face arrest". BBC News. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Taylor, Diane (14 May 2018). "Victims of crime being handed over to immigration enforcement". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- Vasileva, Katya (7 July 2011). "6.5% of the EU population are foreigners and 9.4% are born abroad" (PDF). Statistics in Focus. Eurostat (34/2011). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- "Tougher language requirements announced for British citizenship". Home Office. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- "Life in the UK Test". Home Office. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- "Professor Catherine Barnard: UK will need a seasonal labour scheme as a result of Brexit". 14 January 2022.

Further reading

- Buettner, Elizabeth (University of York) (December 2008). ""Going for an Indian": South Asian Restaurants and the Limits of Multiculturalism in Britain". The Journal of Modern History. 80 (4): 865–901. doi:10.1086/591113. S2CID 144235354.

- Charteris-Black, Jonathan (2006). "Britain as a Container: Immigration Metaphors in the 2005 Election Campaign". Discourse & Society. 17 (5): 563–581. doi:10.1177/0957926506066345. S2CID 145261059.

- Delaney, Enda. Demography, State and Society: Irish Migration to Britain, 1921-1971 (Montreal, 2000)

- Delaney, Enda. The Irish in Post-War Britain (Oxford, 2007)

- Durrheim, Kevin; Okuyan, Mukadder; Twali, Michelle Sinayobye; García-Sánchez, Efraín; Pereira, Adrienne; Portice, Jennie Sofia; Gur, Tamar; Wiener-Blotner, Ori; Keil, Tina F. (2018). "How Racism Discourse Can Mobilize Right-Wing Populism: The Construction of Identity and Alliance in Reactions to UKIP's Brexit 'Breaking Point' Campaign". Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 28 (6): 385–405. doi:10.1002/casp.2347. S2CID 149857477.

- Gabrielatos, Costas; Baker, Paul (2008). "Fleeing, Sneaking, Flooding: A Corpus Analysis of Discursive Constructions of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press, 1996–2005". Journal of English Linguistics. 36 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1177/0075424207311247.

- Hansen, Randall. Citizenship and Immigration in Post-war Britain: the Institutional Origins of a Multicultural Nation (Oxford, 2000),

- Holmes, Colin. John Bull's Island: Immigration and British Society, 1871-1971 (Basingstoke, 1988)

- Khosravinik, Majid (2009). "The Representation of Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in British Newspapers during the Balkan Conflict (1999) and the British General Election (2005)". Discourse & Society. 20 (4): 477–498. doi:10.1075/jlp.9.1.01kho.

- London, Louise. Whitehall & the Jews, 1933-1948: British Immigration Policy & the Holocaust (2000)

- Longpré Nicole. "'An issue that could tear us apart': Race, Empire, and Economy in the British (Welfare) State, 1968," Canadian Journal of History (2011) 46#1 pp. 63–95.

- Lea, Susan; Lynn, Nick (2003). "'A Phantom Menace and the New Apartheid': The Social Construction of Asylum-Seekers in the United Kingdom". Discourse and Society. 14 (4): 425–452. doi:10.1177/0957926503014004002. S2CID 146636834.

- Panayi, Panikos. Immigration, Ethnicity and Racism in Britain, 1815-1945 (1994)

- Paulo, Kathleen. Whitewashing Britain: Race and Citizenship in the Postwar Era (Ithaca, 1997)

- Peach, Ceri. West Indian Migration to Britain: A Social Geography (Oxford, 1968)

- Proctor, James, ed. Writing Black Britain, 1948-1998: An Interdisciplinary Anthology (Manchester, 2000),

- Simkin, John (27 May 2018). "The Politics of Immigration: 1945-2018". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 6 June 2018

- Spencer, Ian R.G British Immigration Policy since 1939: The Making of Multi-Racial Britain (London, 1997)

External links

- Born Abroad: An Immigration Map of Britain (BBC, 2005)

- Destination UK, (BBC News special, 2008)

- Immigration & Nationality Directorate at the Home Office

- Migration Statistics at parliament.uk 17 June 2014 Now dead link, needs removing

- Moving Here, the UK's biggest online database of digitised photographs, maps, objects, documents and audio items from 30 local and national archives, museums and libraries; recording migration experiences of the last 200 years

- Summary of UK immigration rules from the Home Office

- Statement of Changes to the Immigration Rules HC 1078