Athenian Revolution

The Athenian Revolution (508–507 BCE) was a revolt by the people of Athens that overthrew the ruling aristocratic oligarchy, establishing the almost century-long self-governance of Athens in the form of a participatory democracy – open to all free male citizens. It was a reaction to a broader trend of tyranny that had swept through Athens and the rest of Greece.[1]

| Athenian Revolution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the history of democracy | ||||

| ||||

| Date | 508–507 BCE | |||

| Location | ||||

| Resulted in | End of rule by aristocratic oligarchy Establishment of a participatory democracy for all free men of Athens | |||

| Parties | ||||

| Lead figures | ||||

Background

According to legend, Athens was formerly ruled by kings, a situation which may have continued up until the 9th century BCE. During this period, Athens succeeded in bringing the other towns of Attica under its rule. This process of synoikismos – the bringing together into one home – created the largest and wealthiest state on the Greek mainland, but it also created a larger class of people excluded from political life by the nobility.

From later accounts, it is believed that these kings stood at the head of a land-owning aristocracy known as the Eupatridae (the 'well-born'), whose instrument of government was a Council which met on the hill of Areopagus and appointed the chief city officials known as archons. The archon was the chief magistrate in many Greek cities, but in Athens there was a council of archons which exerted a form of executive government. From the late 8th century BCE there were three archons: the archon eponymos (chief magistrate), the polemarchos (commander-in-chief), and the archon basileus (the ceremonial vestige of the Athenian monarchy).[2] The archon eponymous was the chief archon, and presided over meetings of the Boule and Ecclesia, the ancient Athenian assemblies. The archon eponymous remained the titular head of state even under the democracy, though with much reduced political importance. In 753 BCE the perpetual archonship by the Eupatridae[3] were limited to 10 year terms (the "decennial archons").[4] After 683 BCE the offices were held for only a single year.[5]

By the 7th century BCE, social unrest had become widespread, as Athens suffered a land and agrarian crisis. Many Greek city-states had seen the emergence of tyrants, opportunistic noblemen who had taken power on behalf of sectional interests. In Megara, Theagenes had come to power as an enemy of the local oligarchs. His son-in-law, an Athenian nobleman named Cylon, himself made an unsuccessful attempt to seize power in Athens in 632 BCE. However, the coup was opposed by the people of Athens, who forced Cylon and his supporters to take refuge in Athena's temple on the Acropolis. Cylon and his brother escaped, but his followers were cornered by Athens' nine archons. They were persuaded by the archons to leave the temple and stand trial after being assured that their lives would be spared. In an effort to ensure their safety, the accused tied a rope to the temple's statue and went to the trial. On the way, the rope broke of its own accord. The Athenian archons, led by Megacles, took this as the goddess's repudiation of her suppliants and proceeded to stone them to death. Megacles and his genos, the Alcmaeonidae, were exiled from the city for violating the laws against killing suppliants. In order to restore order, the Areopagus appointed Draco to draft strict new laws, replacing the system of oral law with a written legal code enforced by a court of law. However, these "Draconian" reforms ultimately failed to quell the conflict.

Reform and revolution

Seisachtheia

In 594 BCE, Solon, premier archon at the time, issued reforms that defined citizenship in a way that gave each free resident of Attica a political function: Athenian citizens had the right to participate in assembly meetings. By granting the formerly aristocratic role to every free citizen of Athens who owned property, Solon reshaped the social framework of the city-state. Under these reforms, a council of 400 members (with 100 citizens from each of Athens's four tribes) called the boule ran daily affairs and set the political agenda. The Areopagus, which formerly took on this role, remained but subsequently carried on the role of "guardianship of the laws".[6] Another major contribution to democracy was Solon's setting up of an ecclesia or Assembly, which was open to all male citizens, regardless of social class. The Alcmaeonids were also allowed back into the city, during the archonship of Solon.[7] Eventually the moderate reforms of Solon, improving the lot of the poor but firmly entrenching the aristocracy in power, gave Athens some stability. For many of the years to come, the nascent democracy even managed to govern itself without an archon.

Democracy however was threatened by tyranny, as several political factions began to vie for control of the Athenian polis. Peisistratos launched a populist coup and seized the reigns of government in Athens, declaring himself Tyrant. Upon his death, Peisistratos was succeeded to the tyranny by his sons Hippias and Hipparchus, the latter of which was murdered by the tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton. Hippias executed the tyrannicides and it was said that he became a bitter and cruel ruler, executing a large number of citizens and imposing harsh taxes on the Athenian populace.[8] Hippias's cruelty soon created unrest among his subjects. As he began losing control, he sought military support from the Persians and formed alliances with other Greek tyrannies.[9] The Alcmaeonidae family of Athens, which Peisistratus had exiled in 546 BCE, was concerned about Hippias forming alliances with the Persian ruling class, and began planning an invasion to depose him.

In 510 BCE Cleomenes I of Sparta successfully invaded Athens and trapped Hippias on the Acropolis.[10][11] They also took the Pisistratidae children hostage forcing Hippias to leave Athens in order to have them returned safely. Hippias was one of several Greek aristocrats who took refuge in the Achaemenid Empire following reversals at home, other famous ones being Themistocles, Demaratos, Gongylos or Alcibiades.[12]

The Solonian constitution was created by Solon in the early 6th century BC.[13] At the time of Solon the Athenian State was almost falling to pieces in consequence of dissensions between the parties into which the population was divided. Solon wanted to revise or abolish the older laws of Draco. He promulgated a code of laws embracing the whole of public and private life, the salutary effects[14] of which lasted long after the end of his constitution.

Revolution

With the tyrant ousted, the Spartan king installed Isagoras at the head of an oligarchy, made up of Athenian aristocrats that were loyal or sympathetic to Sparta. He found himself opposed by the majority of Athens, particularly the middle and lower classes, who desired a return to democracy. Cleisthenes, of the pro-democracy Alcmaeonidae clan, was expelled from Athens by the Spartan-backed oligarchs, leaving Isagoras unrivalled in power within the city. Isagoras set about dispossessing hundreds of Athenians of their homes and exiling them on the pretext that they too were cursed by the Alcmaeonidae miasma. He also attempted to dissolve the Boule. However, the council resisted, and the Athenian people declared their support for the council and revolted against the oligarchy. Cleomenes, Isagoras and their supporters were forced by regular citizens to flee to the Acropolis, where they were besieged by Athens' populace for two days. On the third day the Athenians made a truce, allowed Cleomenes and Isagoras to escape, and executed 300 of Isagoras' supporters. Cleisthenes was subsequently recalled, along with hundreds of exiles, and he was elected the first archon of a democratic Athens.[15]

Cleisthenes began to institutionalize the democratic revolution. He commissioned a bronze memorial from the sculptor Antenor in honor of the lovers and tyrannicides Harmodius and Aristogeiton, whom Hippias had executed. In order to forestall strife between the traditional clans, which had led to the tyranny in the first place, he changed the political organization from the four traditional tribes, which were based on family relations and which formed the basis of the upper class Athenian political power network, into ten tribes according to their area of residence (their deme,) which would form the basis of a new democratic power structure.[16] Cleisthenes also abolished patronymics in favour of demonymics (a name given according to the deme to which one belongs), thus increasing Athenians' sense of belonging to their local community, thus completely undermining the rule of aristocratic families. He also established sortition – the random selection of citizens to fill government positions rather than kinship or heredity. He also introduced the bouletic oath, "To advise according to the laws what was best for the people".[17] The court system and the Boule were also reorganized and expanded. It was now the role of the Boule to propose laws to the assembly of voters, who convened in Athens around forty times a year for this purpose. The bills proposed could be rejected, passed or returned for amendments by the assembly. Cleisthenes also may have introduced ostracism (first used in 487 BCE), whereby a vote by a plurality of citizens would exile a citizen for 10 years. The initial trend was to vote for a citizen deemed a threat to the democracy (e.g., by having ambitions to set himself up as tyrant). However, soon after, any citizen judged to have too much power in the city tended to be targeted for exile (e.g., Xanthippus in 485/84 BCE).[18] Under this system, the exiled man's property was maintained, but he was not physically in the city where he could possibly create a new tyranny. One later ancient author records that Cleisthenes himself was the first person to be ostracized.[19]

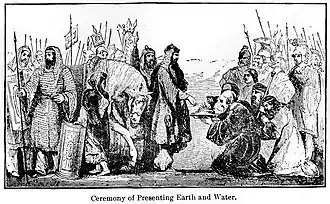

The Spartans thought that a free and democratic Athens would be dangerous to Spartan power, and attempted to recall Hippias from Persia and re-establish the tyranny. Democratic Athens sent an embassy to Artaphernes, brother of Darius I, looking for Persian assistance in order to resist the threats from Sparta.[20][21] Artaphernes asked the Athenians for "Water and Earth", a symbol of submission, if they wanted help from the Achaemenid king.[21] The Athenians ambassadors apparently complied with this request,[20] but then Artaphernes advised the Athenians that they should receive back Hippias, threatening to attack Athens if they did not accept him as their tyrant once more. Nevertheless, the Athenians preferred to remain democratic despite the danger from the Achaemenid Empire, and the ambassadors were disavowed and censured upon their return to Athens.[20] Soon after this, the Ionian Revolt began. It was put down in 494 BCE, but Darius I was intent on punishing Athens for its role in the revolt. In 490 Hippias, still in the service of the Persians, encouraged Darius to invade Greece and attack Athens; when Darius initiated the campaign, Hippias himself accompanied the Persian fleet and suggested Marathon as the place where the Persian invasion of Attica should begin.[22] But never again would the Peisistratids have influence in Athens.[23]

Democracy and counter-revolution

In 462 BCE, the pro-democracy Ephialtes and his political allies began attacking the Areopagus, a council composed of former archons which was a traditionally conservative force. According to Aristotle and some modern historians, Athens had, since about 470 BCE, been governed under an informal "Areopagite constitution", under the leadership of the aristocrat Cimon.[24] The Areopagus had already been losing prestige ever since 486 BCE, when archons were selected by lot. Ephialtes accelerated this process by prosecuting certain members for maladministration.[25] Having thus weakened the prestige of the council, Ephialtes proposed and had passed in the popular assembly a sweeping series of reforms which divided up the powers traditionally wielded by the Areopagus among the democratic council of the Boule, the Ecclesia itself, and the popular courts. Ephialtes took away from the Areopagus their "additional powers, through which it had guardianship of the constitution." The Areopagus merely remained a high court, in control of judging charges of murder and some religious matters. At the same time or soon afterwards, the membership of the Areopagus was extended to the lower level of the propertied citizenship.[26] The success of Ephialtes' reforms was rapidly followed by the ostracism of Cimon, which left Ephialtes and his faction firmly in control of the state, although the fully fledged Athenian democracy of later years was not yet fully established; Ephialtes' reforms appear to have been only the first step in the democratic party's programme.[27] Ephialtes, however, would not live to see the further development of this new form of government; In 461 BCE, he was assassinated, succeeded to the democratic leadership by Pericles.[28]

In the wake of Athens' disastrous defeat in the Sicilian expedition in 413 BCE, a group of aristocrats took steps to limit the radical democracy they thought was leading the city to ruin. Their efforts, initially conducted through constitutional channels, culminated in the establishment of an oligarchy, the Council of 400, in the Athenian coup of 411 BCE. The oligarchy endured for only four months before it was replaced by an even more democratic government. Democratic regimes governed until Athens surrendered to Sparta in 404 BCE, when the government was placed in the hands of the so-called Thirty Tyrants, who were pro-Spartan oligarchs.[29] After a year pro-democracy elements regained control, and democratic forms persisted until the Macedonian army of Phillip II conquered Athens in 338 BCE.[30]

See also

References

- Ober, Josiah (1996). The Athenian Revolution. Princeton University Press. pp. 32–52.

- Gods, Heroes and Tyrants: Greek Chronology in Chaos By Emmet John Sweeney.

- Herodotus, George Rawlinson, Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, Sir John Gardner Wilkinson. The History of Herodotus: A New English Version, Ed. with Copious Notes and Appendices, Illustrating the History and Geography of Herodotus, from the Most Recent Sources of Information; and Embodying the Chief Results, Historical and Ethnographical, which Have Been Obtained in the Progress of Cuneiform and Hieroglyphical Discovery, Volume 3. Appleton, 1882. Pg 316

- Evelyn Abbott. A Skeleton Outline of Greek History: Chronologically Arranged. Pg 27.

- Green, Peter (2009). "Diodorus Siculus on the Third Sacred War". In Marincola, John (ed.). A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons. p. 364. ISBN 978-0-470-76628-6.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Areopagus.

- See Gomme, A Historical Commentary on Athens, on 1.126.12. Megacles' son Alcmaeon held command during the first Sacred War: Plutarch, Solon 11.2.

- Smith, William (1851). A new classical dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, mythology and geography. New York: Harper. p. 671.

- Fine, John V.A. (1983). The Ancient Greeks: A Critical History. Harvard University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-674-03314-6.

- Roper, Brian S. (2013). The History of Democracy: A Marxist Interpretation. Pluto Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-1-84964-713-7.

- Sacks, David; et al. (2009). "Hippias". Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World. Infobase Publishing. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-4381-1020-2.

- Miller, Margaret C. (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-521-60758-2.

- A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, Mythology, Religion, Literature and Art, from the German of Dr. Oskar Seyffert. Page 595

- Effecting or designed to effect an improvement

- Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 20

- Aristotle, Politics 6.4.

- Morris & Raaflaub Democracy 2500?: Questions and Challenges

- Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, Chapter 22

- Aelian, Varia historia 13.24

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-107-00960-8.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00960-8.

- Smith, Willam (1851). A new classical dictionary of Greek and Roman biography, Mythology, and Geography. New York: Harper. p. 671.

- Burn, A. R. (1988). The Pelican History of Greece. London: Penguin. p. 173.

- Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, 64-5. See also Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, 23

- Unless otherwise noted, all details of this campaign are drawn from Aristotle, Constitution of the Athenians, 25

- Thorley, J., Athenian Democracy, Routledge, 2005, pp. 55–56

- Hignett, History of the Athenian Constitution, 217-18

- Plutarch, Pericles, 10.6–7

- Blackwell, Christopher. "The Development of Athenian Democracy". Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy. Stoa. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- "The Final End of Athenian Democracy". PBS.