Attack submarine

An attack submarine or hunter-killer submarine is a submarine specifically designed for the purpose of attacking and sinking other submarines, surface combatants and merchant vessels. In the Soviet and Russian navies they were and are called "multi-purpose submarines".[1] They are also used to protect friendly surface combatants and missile submarines.[2] Some attack subs are also armed with cruise missiles, increasing the scope of their potential missions to include land targets.

Attack submarines may be either nuclear-powered or diesel-electric ("conventionally") powered. In the United States Navy naming system, and in the equivalent NATO system (STANAG 1166), nuclear-powered attack submarines are known as SSNs and their anti-submarine (ASW) diesel-electric predecessors are SSKs. In the US Navy, SSNs are unofficially called "fast attacks".

History

Origins

During World War II, submarines that fulfilled the offensive surface attack role were termed fleet submarines in the U.S. Navy and "ocean-going", "long-patrol", "type 1" or "1st class" by continental European navies.[3][4]

In the action of 9 February 1945, HMS Venturer sank U-864 while both were at periscope depth. This was the first and so far only intentional sinking of a submerged submarine by a submerged submarine. U-864 was snorkeling, thus producing much noise for Venturer's hydrophones (an early form of passive sonar) to detect, and Venturer was fortunate in having over 45 minutes to plot the U-boat's zig-zag course by observing the snorkel mast. Venturer's commander, James S. "Jimmy" Launders, was astute in assuming the U-boat would execute an "emergency deep" maneuver once it heard the torpedoes in the water, thus the "spread" of four torpedoes immediately available was aimed on that assumption. One hit, sinking the U-boat.[5][6]

Beginnings of the attack submarine type

Following World War II, advanced German submarines, especially the Type XXI U-boat, became available to the Allies, particularly the United States Navy and the Soviet Navy. Initially, the Type XVII U-boat, with a Walter hydrogen peroxide-fueled gas turbine allowing high sustained underwater speed, was thought to be more developed than was actually the case, and was viewed as the submarine technology of the immediate future. However, the Type XXI, streamlined and with a high battery capacity for high submerged speed, was fully developed and became the basis for most non-nuclear submarine designs worldwide through the 1950s.[7] In the US Navy, the Greater Underwater Propulsion Power Program (GUPPY) was developed to modernize World War II submarines along the lines of the Type XXI.[8] By 1955 the U.S. Navy was using the term 'attack submarine' to describe the GUPPY conversions and the first postwar submarines (the Tang class and the Darter).[9]

Beginnings of a separate hunter-killer submarine type (SSK)

It was realized that the Soviet Union had acquired Type XXI and other advanced U-boats and would soon be putting their own equivalents into production. In 1948 the US Navy prepared estimates of the number of anti-submarine warfare (ASW)-capable submarines that would be needed to counter the hundreds of advanced Soviet submarines that were expected to be in service by 1960. Two scenarios were considered: a reasonable scenario assuming the Soviets would build to their existing force level of about 360 submarines, and a "nightmare" scenario projecting that the Soviets could build submarines as fast as the Germans had built U-boats, with a force level of 2,000 submarines. The projected US SSK force levels for these scenarios were 250 for the former and 970 for the latter. Additional anti-surface (i.e., 'attack'), guided missile, and radar picket submarines would also be needed. By comparison, the total US submarine force at the end of World War II, excluding obsolescent training submarines, was just over 200 boats.[7]

.jpg.webp)

A small submarine suitable for mass production was designed to meet the SSK requirement. This resulted in the three submarines of the K-1 class (later named the Barracuda class), which entered service in 1951. At 750 long tons (760 t) surfaced, they were considerably smaller than the 1,650 long tons (1,680 t) boats produced in World War II. They were equipped with an advanced passive sonar, the bow-mounted BQR-4, but had only four torpedo tubes. Initially, a sonar located around the conning tower was considered, but tests showed that bow-mounted sonar was much less affected by the submarine's own noise.

While developing the purpose-built SSKs, consideration was given to converting World War II submarines into SSKs. The less-capable Gato class was chosen for this, as some of the deeper-diving Balao- and Tench-class boats were being upgraded as GUPPYs. Seven Gato-class boats were converted to SSKs in 1951–53. These had the bow-mounted BQR-4 sonar of the other SSKs, with four of the six bow torpedo tubes removed to make room for the sonar and its electronics. The four stern torpedo tubes were retained. Two diesel engines were removed, and the auxiliary machinery was relocated in their place and sound-isolated to reduce the submarine's own noise.[7][10]

The Soviets took longer than anticipated to start producing new submarines in quantity. By 1952 only ten had entered service.[11] However, production was soon ramped up. By the end of 1960 a total of 320 new Soviet submarines had been built (very close to the USN's 1948 low-end assumption), 215 of them were the Project 613 class (NATO Whiskey class), a smaller derivative of the Type XXI. Significantly, eight of the new submarines were nuclear-powered.[12][13]

End of the U.S. conventional hunter-killers (SSK)

USS Nautilus, the world's first nuclear submarine, was operational in 1955; the Soviets followed this only three years later with their first Project 627 "Kit"-class SSN (NATO November class). Since a nuclear submarine could maintain a high speed at a deep depth indefinitely, conventional SSKs would be useless against them:

By the fall of 1957, Nautilus had been exposed to 5,000 dummy attacks in U.S. exercises. A conservative estimate would have had a conventional submarine killed 300 times: Nautilus was ruled as killed only 3 times...Using their active sonars, nuclear submarines could hold contact on diesel craft without risking counterattack...In effect, Nautilus wiped out the ASW progress of the past decade.[14]

As the development and deployment of nuclear submarines proceeded, in 1957–59 the US Navy's SSKs were decommissioned or redesignated and reassigned to other duties. It had become apparent that all nuclear submarines would have to perform ASW missions.

Other new technologies

Research proceeded rapidly to maximize the potential of the nuclear submarine for the ASW and other missions. The US Navy developed a fully streamlined hull form and tested other technologies with the conventional USS Albacore, commissioned in 1953. The new hull form was first operationalized with the three conventional Barbel-class boats and the six nuclear Skipjack-class boats, when both classes entered service beginning in 1959.[15][16] The Skipjack was declared the "world's fastest submarine" following trials, although the actual speed was kept secret.

Sonar research showed that a sonar sphere capable of three-dimensional operation, mounted at the very bow of a streamlined submarine, would increase detection performance. This was recommended by Project Nobska, a 1956 study ordered by Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke.[17] The one-off Tullibee in 1960 and the Thresher class starting in 1961 were the first with a bow-mounted sonar sphere; midships torpedo tubes angled outboard were fitted to make room for the sphere.[7][18]

Failure to develop a U.S. nuclear hunter-killer (SSKN)

Tullibee was a type of nuclear-powered SSK; technologically very successful, intentionally slow but ultra-quiet with turbo-electric drive. Her unexpectedly high cost compared with the Thresher proved it was impossible to build a low-cost nuclear SSK (several nuclear reactor features could not be scaled down beyond a certain point, including radiation shielding). This result coupled with her lower performance was judged to be not cost-effective and the type was not repeated; the Navy decided to merge the hunter-killer role with the attack submarines, making the terms interchangeable.[19] Thresher was faster and had an increased diving depth, carried twice as many torpedoes, included comparable sound silencing improvements, and was commissioned only nine months later.[20]

Thresher's loss in April 1963 triggered a major redesign of subsequent US submarines known as the SUBSAFE program.[16] However, Thresher's general arrangement and concept were continued in all subsequent US Navy attack submarines.

Later developments

Britain commissioned its first nuclear attack submarine HMS Dreadnought in 1963 with a US S5W reactor. At the same time as the Dreadnought construction, attempts were made to transfer US reactor technology to Canada and the Netherlands. Admiral Hyman G. Rickover considered such technology to be obvious, but a visit to the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Lenin reportedly "appalled him" and convinced him that he should cancel the transfers to retain secrets.[21][22]

The first fully streamlined Soviet attack submarines were the Project 671 "Yorsh" class (NATO Victor I class), which first entered service in 1967.[12][23]

China commissioned its first nuclear attack submarine Changzheng 1 in 1974, and France its first Rubis-class submarine in 1983.[24][25]

The only time in history that a nuclear attack submarine engaged and sank an enemy warship was in the Falklands War, when on 2 May 1982 the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror torpedoed and sank the Argentine light cruiser ARA General Belgrano.[26]

As of 2021 Brazil has a nuclear attack submarine under construction, India has finalized a nuclear attack submarine interim design, and Australia has started a nuclear attack submarine program under the AUKUS security pact with UK and US assistance.[28][29][30]

Modern conventional submarines

Conventional attack submarines have however remained relevant throughout the nuclear era, with the British Oberon class and the Soviet Romeo, Foxtrot, Tango and Kilo classes being good examples which served during the Cold War. With the advent of air-independent propulsion technology, these submarines have grown more and more capable. Examples include the Type 212, Scorpène and Gotland classes of submarine. The US Navy leased HSwMS Gotland to perform the opposing force role during ASW exercises tactics.[31] The Gotland caused a stir in 2005 when during training it "sank" the American carrier USS Ronald Reagan.[32][33]

Operators

Current operators

Algerian National Navy operates six Kilo-class submarines.

Algerian National Navy operates six Kilo-class submarines. Argentine Navy operates one Type 209 submarine as a pier-side trainer; one TR-1700-class submarine remains in inventory but is inactive.

Argentine Navy operates one Type 209 submarine as a pier-side trainer; one TR-1700-class submarine remains in inventory but is inactive. Royal Australian Navy operates six Collins-class submarines.

Royal Australian Navy operates six Collins-class submarines. Bangladesh Navy operates two Ming-class submarines.

Bangladesh Navy operates two Ming-class submarines. Brazilian Navy operates five Type 209 submarines and three Riachuelo-class submarines.

Brazilian Navy operates five Type 209 submarines and three Riachuelo-class submarines. Royal Canadian Navy operates four Victoria-class submarines.

Royal Canadian Navy operates four Victoria-class submarines. Chilean Navy operates two Type 209 submarines and two Scorpène-class submarines.

Chilean Navy operates two Type 209 submarines and two Scorpène-class submarines. People's Liberation Army Navy operates 6 Shang-class submarines, 3 Han-class submarines, 17 Yuan-class submarines, 13 Song-class submarines, 12 Kilo-class submarines, and 4 Ming-class submarines.

People's Liberation Army Navy operates 6 Shang-class submarines, 3 Han-class submarines, 17 Yuan-class submarines, 13 Song-class submarines, 12 Kilo-class submarines, and 4 Ming-class submarines. Republic of China Navy operates two Zwaardvis-class submarines, one Tench-class submarine and one Balao-class submarine.

Republic of China Navy operates two Zwaardvis-class submarines, one Tench-class submarine and one Balao-class submarine. Colombian National Navy operates two Type 209 submarines.

Colombian National Navy operates two Type 209 submarines. Ecuadorian Navy operates two Type 209 submarines.

Ecuadorian Navy operates two Type 209 submarines. Egyptian Navy operates four Type 209 submarines and four Romeo-class submarines.

Egyptian Navy operates four Type 209 submarines and four Romeo-class submarines. French Navy operates four Rubis-class submarines and two Barracuda-class submarines.

French Navy operates four Rubis-class submarines and two Barracuda-class submarines. German Navy operates six Type 212 submarines.

German Navy operates six Type 212 submarines. Hellenic Navy operates six Type 209 submarines and four Type 214 submarines.

Hellenic Navy operates six Type 209 submarines and four Type 214 submarines. Indian Navy operates four Type 209 submarines, five Scorpène-class submarines, and seven Sindhughosh-class submarines.

Indian Navy operates four Type 209 submarines, five Scorpène-class submarines, and seven Sindhughosh-class submarines. Indonesian Navy operates three Nagapasa-class submarines and one Cakra-class submarine.

Indonesian Navy operates three Nagapasa-class submarines and one Cakra-class submarine. Islamic Republic of Iran Navy operates three Kilo-class submarines.

Islamic Republic of Iran Navy operates three Kilo-class submarines. Israeli Navy operates six Dolphin-class submarines.

Israeli Navy operates six Dolphin-class submarines. Italian Navy operates four Type 212 submarines and four Sauro-class submarines.

Italian Navy operates four Type 212 submarines and four Sauro-class submarines. Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force operates 12 Sōryū-class submarines, 9 Oyashio-class submarines, and 2 Taigei-class submarines.[34]

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force operates 12 Sōryū-class submarines, 9 Oyashio-class submarines, and 2 Taigei-class submarines.[34].png.webp) Korean People's Navy operates 20 Romeo-class submarines.

Korean People's Navy operates 20 Romeo-class submarines. Republic of Korea Navy operates nine Jang Bogo-class submarines, nine Type 214 submarines, and two KSS-III submarines.

Republic of Korea Navy operates nine Jang Bogo-class submarines, nine Type 214 submarines, and two KSS-III submarines. Royal Malaysian Navy operates two Scorpène-class submarines.

Royal Malaysian Navy operates two Scorpène-class submarines. Myanmar Navy operates a single Kilo-class submarine, gifted by India,[35] and a single Ming-class submarine, purchased from China.

Myanmar Navy operates a single Kilo-class submarine, gifted by India,[35] and a single Ming-class submarine, purchased from China. Royal Netherlands Navy operates four Walrus-class submarines.

Royal Netherlands Navy operates four Walrus-class submarines. Royal Norwegian Navy operates six Ula-class submarines.

Royal Norwegian Navy operates six Ula-class submarines. Pakistan Navy operates five Agosta-class submarines.

Pakistan Navy operates five Agosta-class submarines..svg.png.webp) Peruvian Navy operates six Type 209 submarines.

Peruvian Navy operates six Type 209 submarines. Polish Navy operates one Kilo-class submarine.

Polish Navy operates one Kilo-class submarine. Portuguese Navy operates two Type 214 submarines.

Portuguese Navy operates two Type 214 submarines..svg.png.webp) Romanian Naval Forces possesses a single Kilo-class submarine, though it is not operational.

Romanian Naval Forces possesses a single Kilo-class submarine, though it is not operational. Russian Navy operates 10 Akula-class submarines, 2 Victor III-class submarines, two Sierra-class submarines, and c. 21 Kilo-class submarines (of which nine are the "Improved Kilo" variant).

Russian Navy operates 10 Akula-class submarines, 2 Victor III-class submarines, two Sierra-class submarines, and c. 21 Kilo-class submarines (of which nine are the "Improved Kilo" variant). Republic of Singapore Navy operates two Sjöormen-class submarines and two Västergötland-class submarines, all purchased from Sweden.

Republic of Singapore Navy operates two Sjöormen-class submarines and two Västergötland-class submarines, all purchased from Sweden. South African Navy operates three Type 209 submarines.

South African Navy operates three Type 209 submarines. Spanish Navy operates two Agosta-class submarines.

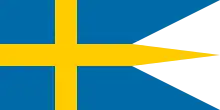

Spanish Navy operates two Agosta-class submarines. Swedish Navy operates three Gotland-class submarines and one Södermanland-class submarine.

Swedish Navy operates three Gotland-class submarines and one Södermanland-class submarine. Turkish Navy operates 12 Type 209 submarines.

Turkish Navy operates 12 Type 209 submarines. Royal Navy operates five Astute-class submarines and one Trafalgar-class submarine.

Royal Navy operates five Astute-class submarines and one Trafalgar-class submarine. United States Navy operates 26 Los Angeles-class submarines, three Seawolf-class submarines, and 21 Virginia-class submarines.

United States Navy operates 26 Los Angeles-class submarines, three Seawolf-class submarines, and 21 Virginia-class submarines..svg.png.webp) Bolivarian Navy of Venezuela operates two Type 209 submarines.

Bolivarian Navy of Venezuela operates two Type 209 submarines. Vietnam People's Navy operates six Kilo-class submarines.

Vietnam People's Navy operates six Kilo-class submarines.

Former operators

Albanian Naval Force retired all four of its Whiskey-class submarines in 1989.

Albanian Naval Force retired all four of its Whiskey-class submarines in 1989. Bulgarian Navy decommissioned its last Romeo-class submarine, Slava in 2011.

Bulgarian Navy decommissioned its last Romeo-class submarine, Slava in 2011. Cuban Revolutionary Navy retired all three of its Foxtrot-class submarines in the 1990s.

Cuban Revolutionary Navy retired all three of its Foxtrot-class submarines in the 1990s. Royal Danish Navy retired its last two Kobben-class submarines and its lone Näcken-class submarine in 2005.

Royal Danish Navy retired its last two Kobben-class submarines and its lone Näcken-class submarine in 2005. Libyan Navy retired its six Foxtrot-class submarines from active service in 1984.

Libyan Navy retired its six Foxtrot-class submarines from active service in 1984. Montenegrin Navy decommissioned its last Heroj-class submarine in 2006.

Montenegrin Navy decommissioned its last Heroj-class submarine in 2006. Navy of Serbia and Montenegro transferred its entire navy to Montenegro upon their independence in 2006.

Navy of Serbia and Montenegro transferred its entire navy to Montenegro upon their independence in 2006. Syrian Arab Navy retired all three of its Whiskey-class submarines in 1993.

Syrian Arab Navy retired all three of its Whiskey-class submarines in 1993. Ukrainian Navy only submarine, Zaporizhzhia, was captured by the Russian Navy during the 2014 Annexation of Crimea.

Ukrainian Navy only submarine, Zaporizhzhia, was captured by the Russian Navy during the 2014 Annexation of Crimea.

Former operators (pre-modern attack)

Austro-Hungarian Navy lost its entire fleet following the Empire's collapse after World War I.

Austro-Hungarian Navy lost its entire fleet following the Empire's collapse after World War I. Estonian Navy two Kalev-class submarines were seized by the Soviet Union in 1940. After Estonia regained independence in 1991, it took back EML Lembit, and was kept in ceremonial commission as the flagship until 2011.

Estonian Navy two Kalev-class submarines were seized by the Soviet Union in 1940. After Estonia regained independence in 1991, it took back EML Lembit, and was kept in ceremonial commission as the flagship until 2011. Finnish Navy forced to decommission all five of its submarines following World War II under the Paris Peace Treaty.

Finnish Navy forced to decommission all five of its submarines following World War II under the Paris Peace Treaty. Latvian Naval Forces two Ronis-class submarines were seized by the Soviet Union in 1940.

Latvian Naval Forces two Ronis-class submarines were seized by the Soviet Union in 1940. Royal Thai Navy decommissioned its last Matchanu-class submarine in 1951.

Royal Thai Navy decommissioned its last Matchanu-class submarine in 1951.

See also

- List of submarine classes in service

- List of submarine operators

- Nuclear navy – Navy with ships powered by nuclear energy

- Coastal submarine

- History of submarines – Aspect of history

References

Citations

- Gorshkov (1979), p. 55.

- "Attack Submarine Info". US Navy. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Friedman (1995), pp. 99–104.

- le Masson, p. 143

- Jones 1986, p. 197.

- Preisler & Sewell 2013, pp. 7, 16, 164–167, 183.

- Friedman (1994), pp. 75–85.

- GUPPY and other diesel boat conversions page

- Friedman (1994), p. 64.

- List of USN SSKs

- "Russian ships website in English, conventional submarines page". Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- "Russian ships website in English, nuclear submarines page". Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- Gardiner & Chumbley (1995), pp. 396–401.

- Friedman (1994), p. 109.

- Friedman (1994), pp. 31–35, 242.

- Gardiner & Chumbley (1995), pp. 605–606.

- Friedman (1994), pp. 109–113.

- US Navy Submarine Warfare Division, Technical Innovations of the Submarine Force, retrieved 14 December 2014 Archived December 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Friedman (1994), pp. 134–138.

- Friedman (1994), pp. 235, 243.

- Gardiner & Chumbley (1995), p. 529.

- Friedman (1994), p. 127.

- Gardiner & Chumbley (1995), pp. 403–406.

- "深海蓝鲨—中国海军091,093型攻击核潜艇_网易新闻中心". 2009-08-03. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- (in French) Déconstruction : le SNA « Rubis » attendu début 2017 à Cherbourg, le marin.fr

- Rossiter (2009), pp. 305–318, 367–377.

- Pubby, Manu (2020-02-21). "India's Rs 1.2 lakh crore nuclear submarine project closer to realisation". The Economic Times. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- Gupta, Shishir (2021-03-24). "For Navy, 6 nuclear-powered submarines take priority over 3rd aircraft carrier". The Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- Prime Minister; Minister for Defence; Minister for Foreign Affairs; Minister for Women (16 September 2021). "Australia to pursue Nuclear-powered Submarines through new Trilateral Enhanced Security Partnership". Prime Minister of Australia (Press release). Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. - "SSK Gotland Class (Type A19)". Naval Technology. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- Roblin, Sebastien (2016-11-13). "Sweden's Super Stealth Submarines Are So Lethal They 'Sank' a U.S. Aircraft Carrier". The National Interest. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "How a Plucky Swedish Sub Took Out a US Carrier All on Its Own". Popular Mechanics. 2018-04-13. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- "Japan Commissions 'Hakugei' 「はくげい」2nd Taigei Class Submarine". Naval News. 20 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- "With an eye on China, India gifts submarine to Myanmar". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

Sources

- Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- Friedman, Norman (1994). U.S. Submarines Since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 1-55750-260-9.

- Gorshkov, Sergei Georgievich (1979). The Sea Power of the State (2nd ed.). Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-961-8.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chumbley, Stephen (1995). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1947–1995. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55750-132-7.

- Jones, G. P. (1986). Submarines versus U-Boats. London: William Kimber. ISBN 978-0-7183-0626-7.

- le Masson, Henri (1969). Navies of the Second World War. Vol. The French Navy 1. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

- Preisler, J.; Sewell, K. (2013) [2012]. Code-Name Caesar: The Secret Hunt for U-boat 864 during World War II (repr. Souvenir Press, London ed.). New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-285-64203-4.

- Rossiter, Mike (2009). Sink the Belgrano. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4070-3411-9. OCLC 1004977305.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

External links

Media related to Attack submarines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Attack submarines at Wikimedia Commons