Auberge Ravoux

The Auberge Ravoux is a French historic landmark located in the heart of the village of Auvers-sur-Oise.[1] It is known as the House of Van Gogh (Maison de Van Gogh) because the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh spent the last 70 days of his life as a lodger at the auberge. During his stay at Auvers, Van Gogh created more than 80 paintings and 64 sketches before shooting himself in the chest on 27 July 1890 and dying two days later on 29 July 1890. The auberge (inn) has been restored as a museum and tourist attraction. The room where Van Gogh lived and died has been restored and can be viewed by the public.[2]

Early history (1876–1889)

The auberge was built in the mid-nineteenth century as a family home on the main road leading to Pontoise. Various parts of earlier buildings were incorporated into the auberge – including an entire eighteenth-century wall. The auberge was ideally situated in front of the Town Hall. The daughter of Mr Levert, the original owner, put the centrality of the location to use by opening a retail wine business. The picturesqueness of the village, as well as its proximity and railway connection to Paris, made it a popular destination for artists, and during the mid- to late nineteenth century an influx of painters, such as Daubigny, Cézanne, Pissarro, Daumier and Corot, saw the village become an artist's colony comparable to Barbizon.[3]

Van Gogh’s stay (20 May 1890 – 29 July 1890) and suicide

In 1889 the lease on the house was taken on by Arthur Gustave Ravoux, who transformed the business into an inn popular with the artistic community in Auvers. During Van Gogh's stay, the rooms were all occupied by Dutch and American painters. The Spanish artist Nicolás Martínez Valdivieso, who lived nearby, took his meals at the auberge with Van Gogh.[4]

Van Gogh arrived in Auvers-sur-Oise on 20 May 1890. He had spent a year in a convalescent home in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence and wanted to settle in the North, closer to Paris. Camille Pissarro, a friend of Van Gogh's, suggested that he go to Auvers-sur-Oise where Dr Gachet lived and could keep an eye on Van Gogh. Dr Gachet had treated mental patients before and was interested in and sympathetic to the arts. The doctor was immortalized in a portrait Van Gogh made of him in June of that year, which fetched a record price of $82.5 million in 1990.

Upon arrival in Auvers, Van Gogh decided to stay at the Auberge Ravoux, mainly because it was cheaper than the hotel proposed by Dr. Gachet, which charged 6 francs a day for full board accommodation. At the Auberge Ravoux, Vincent paid 3 francs 50 a day, half board, and rented room 5, a tiny attic room measuring 75 square feet (7.0 m2) and containing only a bed, a dressing table and a built-in cupboard. He stored his paintings and drawings in a shed at the back of the inn.[5] He became acquainted with Arthur Ravoux and his family and painted a portrait of Adeline Ravoux, the eldest daughter of Ravoux, on more than one occasion. Van Gogh was charmed by the village and in a letter to his brother Theo van Gogh praised its old thatched roofs and colours, calling it “profoundly beautiful”.[6] He found the juxtaposition between the rustic country life and recent modern additions such as the railway and the bridge on the River Oise fascinating. He was in good health, covering large distances with his painting gear and painting as much as he could.

Despite his love of his new surroundings and his feverish activity, on the morning of 27 July 1890, Van Gogh walked into a field and shot himself in the chest. The bullet was deflected by a rib and lodged in his stomach.[7] He survived the impact and managed to walk back to the auberge.[8] Adeline Ravoux later recalled:[9]

"Vincent walked bent, holding his stomach, again exaggerating his habit of holding one shoulder higher than the other. […] [He] crossed the hall, took the staircase and climbed to his bedroom. I was witness to this scene. Vincent made such a strange impression on us that Father got up and went to the staircase to see if he could hear anything.

He thought he could hear groans, went up quickly and found Vincent on his bed, laid down in a crooked position, knees up to his chin, moaning loudly. “What’s the matter,” said Father, “are you ill?” Vincent then lifted his shirt and showed him a small wound in the region of the heart. Father cried: “Malheureux [poor soul], what have you done?”

“I have tried to kill myself,” replied Van Gogh."

The following morning two gendarmes arrived to enquire into a rumour about a suicide attempt. One of them began to question Van Gogh in an aggressive manner. Van Gogh replied:

"Gendarme, my body is mine and I am free to do what I want with it. Do not accuse anybody, it is I that wished to commit suicide."

Arthur Ravoux dissuaded the gendarme from questioning him further.[9]

Two days later Vincent succumbed to his wounds in the presence of his brother Theo van Gogh. The body was laid out in the back room of the auberge.[5] The coffin was made by Vincent Levert, whose son Raoul Levert was the subject of Vincent's Child with an orange.[4] Émile Bernard described the coffin as covered in a simple white cloth and strewn with yellow flowers,[10]

"...the sunflowers that he loved so much, yellow dahlias, yellow flowers everywhere. It was, you will remember, his favourite colour, the symbol of the light that he dreamed of as being in people's hearts as well as in works of art."

His easel, folding stool and brushes were placed in front of the coffin.[10] The room was decorated with Vincent's paintings and drawings.[5] Anton Hirschig, a fellow lodger at the auberge, later recalled them,[5]

"There was the one with the fields billowing into the horizon, the one with the sun hanging in the middle, the one with the town hall decorated with flags and lanterns, the portrait of the girl in blue with the blue background and many others ..."

while Adeline Ravoux mentioned The Church at Auvers, Irises, Daubigny's Garden and Child with an orange in her memoir.[9] Bernard mentioned The Pietà and Prisoners exercising,[10]

" ... a very beautiful and sad [study] based on Delacroix's La vierge et Jesus. Convicts walking in a circle surrounded by high prison walls, a canvas inspired by Doré of a terrifying ferocity and which is also symbolic of his end. Wasn't life like that for him, a high prison like this with such high walls - so high…and these people walking endlessly round this pit, weren't they the poor artists, the poor damned souls walking past under the whip of Destiny?…"

Hirschig also recalled that the coffin was poorly made and continuously leaked fluid, forcing them to use carbol as it was so hot.[5]

Van Gogh was buried on 30 July at the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise at a funeral attended by Theo van Gogh, Andries Bonger, Charles Laval, Lucien Pissarro, Émile Bernard, Julien Tanguy and Dr. Gachet amongst some 20 family and friends, as well as a number of locals (including Arthur Ravoux).[4][9] The Catholic abbé declined to host a funeral service for a suicide. He could not, however, refuse a burial because the cemetery was a public one.[4] Dr. Gachet delivered an emotional address at the funeral. The funeral was described by Émile Bernard in a moving letter to Albert Aurier and Bernard later painted a picture of it from memory.[4][10][11]

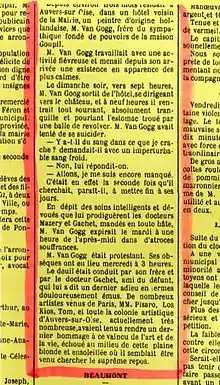

Van Gogh's death and funeral was reported by the local newspaper Le Régional in its edition dated 7 August 1890.[4][7] The report makes it clear that Van Gogh suffered at the end, expiring after "terrible suffering" (dans d'atroces souffrances), an account confirmed by Hirschig in a 1911 letter to Albert Plasschaert.[5] Theo recorded Vincent's last words as "the sadness will last forever" in a letter to their sister Elisabeth dated 5 August 1890.[12]

Thereafter room 5 was tainted by his suicide and never rented out again.[3] Van Gogh's stay at the Auberge Ravoux had been one of prolific creation: in 70 days he created more than 80 paintings and 64 sketches, amongst which were the Portrait of Dr. Gachet, Wheatfield with Crows, Auvers Town Hall on 14 July 1890 and Daubigny's Garden:

Van Gogh, who loved to feast on the light, forever transformed his low-lit little room into a room with a view: it has only one skylight to watch the day pass through, but it opens a window onto ourselves.

— Wouter van der Veen and Peter Knapp, Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days

1890–1985: The House of Van Gogh

The Ravoux family left Auvers-sur-Oise in 1892. The period around the turn of the century saw the beginning of a new era of modernity, notably the installation of gas street lamps and telephones in Auvers. After the first exhibitions of his work in the late 1880s, Van Gogh gradually became an artist of international renown and, eventually, a household name. In the years between 1901 and 1915, major exhibitions of his work were held in cities ranging from Paris to New York. Around this time, the Blot family, who were the leaseholders of the auberge at that time, started inviting people to view Vincent's room. In 1926 the name of the auberge was changed to The House of Van Gogh. The period during and after the Second World War saw a decline in interest in the auberge, but in 1952 it was bought by Roger and Micheline Tagliana who restored Vincent's room with the help of Adeline Ravoux.[3] The film Lust for Life by Vincente Minnelli was filmed in Auvers and The House of Van Gogh was featured, garnering much publicity for the location.

1986-present

Since 1986 the auberge has been under the supervision of Dominique-Charles Janssens. An award-winning architect, Bernard Schoebel, specializing in the restoration of historical landmarks, was chosen to renovate the auberge. Van Gogh's room was painstakingly restored to its original condition. The dining room where Van Gogh took his meals was also restored and is now a restaurant serving meals inspired by nineteenth-century regional cuisine. A slide show has been set up in the attic detailing van Gogh's life and oeuvre and including extracts from his letters as well as period photographs.[3]

Van Gogh's room

Since 1993 more than one million people have visited Van Gogh's room. Room 5, restored to its original condition, can be viewed by the public. The nails upon which Van Gogh hung his canvases are still in the wall. Room 5 is bare and unfurnished, but the sparsely furnished room next door inhabited by fellow Dutch artist, Anton Hirschig, provides insight into the spartan atmosphere of the artist's final surroundings. The room contains a high-tech secure show-case, as it is hoped that room 5 will one day house a Van Gogh painting. In a letter to his brother Theo, written during his stay at the Auberge Ravoux, Vincent once confessed his longing to exhibit his work in a café: “Some day or another, I believe I will find a way to have my own exhibition in a café”.[13] The Institute of Van Gogh, via Van Gogh's dream, a non-profit organization created in 1987, believes that too many of Van Gogh's works are in private hands and thus inaccessible to the public, and aims to fulfill Vincent's wish by purchasing one of his Auvers paintings and exhibiting it in the room where he died.[14] In his 37 years, Van Gogh had lived at more than thirty different addresses.[2]

See also

References

- Base Mérimée: Auberge Ravoux, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- van der Veen, Wouter; Knapp, Peter (2010). Van Gogh in Auvers: His Last Days. Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-301-8.

- Alexandra Leaf, Fred Leeman, Van Gogh’s Table at the Auberge Ravoux, Artisan, New York, 2001.

- Obst, Andreas (2010). Records and deliberations about Vincent van Gogh's first grave in Auvers-sur-Oise. Lauenau: Het Geheugen van Nederland.

- van Crimpen, Han (1988). "Friends remember Van Gogh in 1912". In Haruo Arikawa; et al. (eds.). Vincent van Gogh. International Symposium Tokyo – October 17-19, 1985. Tokyo. pp. 73–90.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "To Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger. Auvers-sur-Oise, Tuesday, 20 May 1890". Vincent van Gogh: The Letters. Van Gogh Museum. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Le Régional. Beaumont-sur-Oise: Private archive of M. Jean-Pierre Mantel, Auvers-sur-Oise. 7 August 1890.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers, Ex. cat., Metropolitan Museum of Art, USA, 1986.

- Adeline Ravoux (1957). "Souvenirs sur le séjour de Vincent van Gogh à Auvers-sur-Oise". Les Cahiers de Van Gogh; 1 (in French). pp. 7–17.

- "Letter from Emile Bernard to Albert Aurier". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Walther, Ingo F.; Metzger, Rainer (2006). Van Gogh: The Complete Paintings. Taschen. p. 692. ISBN 3-8228-5068-3.

- "Letter from Theo van Gogh to Elisabeth van Gogh". WebExhibits. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- "881". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- "Van Gogh's dream". Retrieved 14 July 2011.