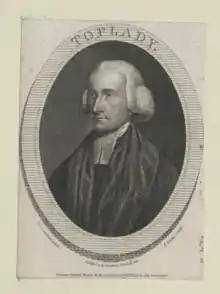

Augustus Toplady

Augustus Montague Toplady /ˈtɒpləˌdiː/ (4 November 1740 – 11 August 1778) was an Anglican cleric and hymn writer. He was a major Calvinist opponent of John Wesley. He is best remembered as the author of the hymn "Rock of Ages". Three of his other hymns – "A Debtor to Mercy Alone", "Deathless Principle, Arise" and "Object of My First Desire" – are still occasionally sung today.

Background and early life, 1740–55

Augustus Toplady was born in Farnham, Surrey, England in November 1740. His father, Richard Toplady, was probably from Enniscorthy, County Wexford in Ireland. Richard Toplady became a commissioned officer in the Royal Marines in 1739; by the time of his death, he had reached the rank of major. In May 1741, shortly after Augustus' birth, Richard participated in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias (1741), the most significant battle of the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42), during the course of which he died, most likely of yellow fever,[1] leaving Augustus' mother to raise the boy alone.

Toplady's mother, Catherine, was the daughter of Richard Bate, who was the incumbent of Chilham from 1711 until his death in 1736. Catherine and her son moved from Farnham to Westminster. He attended Westminster School from 1750 to 1755.

Trinity College, Dublin: 1755–60

In 1755, Catherine and Augustus moved to Ireland, and Augustus was enrolled in Trinity College Dublin.

Shortly thereafter, in August 1755, the 15-year-old Toplady attended a sermon preached by James Morris, a follower of John Wesley, in a barn in Codymain, co. Wexford (though in his Dying Avowal, Toplady denies that the preacher was directly connected to Wesley, with whom he had developed a bitter relationship). He would remember this sermon as the time at which he received his effectual calling from God.

Toplady underwent a religious awakening in August 1755, "but not, as has been falsely reported, under Mr. John Wesley, or any preacher connected with him". . In his own diary, he wrote ""I was awakened in the month of August, 1755, but not, as has been falsely reported, under Mr. John Wesley, or any preacher connected with him. Though awakened in 1755. I was not led into a full and clear view of all the doctrines of grace, till the year 1758, when, through the great goodness of God, my Arminian prejudices received an effectual shock, in reading Dr. Manton’s Sermons on the 17th of St. John".[2]

In 1759, Toplady published his first book, Poems on Sacred Subjects.

Following his graduation from Trinity College in 1760, Toplady and his mother returned to Westminster. There, Toplady met and was influenced by several prominent Calvinist ministers, including George Whitefield, John Gill, and William Romaine. It was John Gill who in 1760 urged Toplady to publish his translation of Zanchius's work on predestination, Toplady commenting that "I was not then, however, sufficiently delivered from the fear of man."[3]

Church ministry: 1762–78

In 1762, Edward Willes, the Bishop of Bath and Wells, ordained Toplady as an Anglican deacon, appointing him curate of Blagdon, located in the Mendip Hills of Somerset.

Toplady wrote his famous hymn Rock of Ages in 1763. A local tradition – discounted by most historians – holds that he wrote the hymn after seeking shelter under a large rock at Burrington Combe, a magnificent ravine close to Blagdon, during a thunderstorm.

Upon being ordained priest in 1764, Toplady returned to London briefly, and then served as curate of Farleigh Hungerford for a little over a year (1764–65). He then returned to stay with friends in London for 1765–66.

In May 1766, he became incumbent of Harpford and Venn Ottery, two villages in Devon. In 1768, however, he learned that he had been named to this incumbency because it had been purchased for him; seeing this as simony, he chose to exchange the incumbency for the post of vicar of Broadhembury, another Devon village. He would serve as vicar of Broadhembury until his death, although he received leave to be absent from Broadhembury from 1775 on.

Toplady never married, though he did maintain friendships with two women. The first was Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, the founder of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, a Calvinist Methodist series of congregations. Toplady first met Huntingdon in 1763, and preached in her chapels several times in 1775 during his absence from Broadhembury. The second was Catharine Macaulay, whom he first met in 1773, and with whom he spent a large amount of time in the years 1773–77.

Animals and Natural World

Toplady was a prolific essayist and letter correspondent and wrote on a wide range of topics. He was interested in the natural world and in animals. He composed a short work Sketch of Natural History, with a few particulars on Birds, Meteors, Sagacity of Brutes, and the solar system, wherein he set down his observations about the marvels of nature, including the behaviour of birds, and illustrations of wise actions on the part of various animals. Toplady also considered the problem of evil as it relates to the sufferings of animals in A Short Essay on Original Sin, and in a public debate delivered a speech on Whether unnecessary cruelty to the brute creation is not criminal?. In this speech he repudiated brutality towards animals and also affirmed his belief that the Scriptures point to the resurrection of animals.[4] Toplady's position about animal brutality and the resurrection were echoed by his contemporaries Joseph Butler, Richard Dean, Humphry Primatt and John Wesley, and throughout the nineteenth century other Christian writers such as Joseph Hamilton, George Hawkins Pember, George N. H. Peters, Joseph Seiss, and James Macauley developed the arguments in more detail in the context of the debates about animal welfare, animal rights and vivisection.[5][6][7]

Calvinist controversialist: 1769–78

Toplady's first salvo into the world of religious controversy came in 1769 when he wrote a book in response to a situation at the University of Oxford. Six students had been expelled from St Edmund Hall because of their Calvinist views, which Thomas Nowell criticised as inconsistent with the views of the Church of England. Toplady then criticised Nowell's position in his book The Church of England Vindicated from the Charge of Arminianism, which argued that Calvinism, not Arminianism, was the position historically held by the Church of England.

1769 also saw Toplady publish his translation of Zanchius's Confession of the Christian Religion (1562), one of the works which had convinced Toplady to become a Calvinist in 1758. Toplady entitled his translation The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted.[8] This work drew a vehement response from John Wesley, thus initiating a protracted pamphlet debate between Toplady and Wesley about whether the Church of England was historically Calvinist or Arminian. This debate peaked in 1774, when Toplady published his 700-page The Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England, a massive study which traced the doctrine of predestination from the period of the Early Church through to William Laud. The section about the Synod of Dort contained a footnote identifying five basic propositions of the Calvinist faith, arguably the first appearance in print of the summary of Calvinism known as the five points of Calvinism.

The relationship between Toplady and Wesley that had initially been cordial, involving exchanges of letters in Toplady's Arminian days, became increasingly bitter and reached its nadir with the "Zanchy affair".[9] Wesley took exception to the publication of Toplady's translation of Zanchius's work on predestination in 1769 and published, in turn, an abridgment of that work titled The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted, adding his own comment that "The sum of all is this: One in twenty (suppose) of mankind are elected; nineteen in twenty are reprobated. The elect shall be saved, do what they will; the reprobate will be damned, do what they can. Reader believe this, or be damned. Witness my hand." Toplady viewed the abridgment and comments as a distortion of his and Zanchius's views and was particularly enraged that the authorship of these additions was attributed to him, as though he approved of the content.

Toplady published a response in the form of A Letter to the Rev Mr John Wesley; Relative to His Pretended Abridgement of Zanchius on Predestination.[10] Wesley never publicly accepted any wrongdoing on his part and seemingly denied his authorship of the comments contained in his abridgement when, in his 1771 work The Consequence Proved that responded to Toplady's letter, he ascribed his additions to Toplady.[lower-alpha 1] Subsequently, Wesley avoided direct correspondence with Toplady, famously stating in a letter of 24 June 1770 that "I do not fight with chimney-sweepers. He is too dirty a writer for me to meddle with. I should only foul my fingers. I read his title-page, and troubled myself no farther. I leave him to Mr Sellon. He cannot be in better hands."[11]

Last years

Toplady spent his last three years mainly in London, preaching regularly in a French Calvinist chapel at Orange Street (off of Haymarket), most spectacularly in 1778, when he appeared to rebut charges being made by Wesley's followers that he had renounced Calvinism on his deathbed.

Toplady died of tuberculosis on 11 August 1778. He was buried at Whitefield's Tabernacle, Tottenham Court Road.

Hymns

- A Debtor To Mercy Alone n. 7 in The Believers Hymn Book

- Compared with Christ, in all beside n. 760 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772)

- Deathless spirit, now arise n. 1381 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776)

- Holy Ghost, dispel our sadness n. 80 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776). Modernising of John Christian Jacobi's translation (1725) of Paul Gerhardts hymn from 1653.

- How happy are the souls above n. 1434 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776) (? A. M. Topladys text)

- Inspirer and hearer of prayer n. 30 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774)

- O thou, that hear'st the prayer of faith n. 642 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1176)

- Praise the Lord, who reigns above n. 160 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759)

- Rock of ages, cleft for me n. 697 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1776)

- Surely Christ thy griefs hath borne n. 443 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1759)

- What, though my frail eye-lids refuse n. 29 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1774)

- When langour and disease invade n. 1032 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1778)

- Your harps, ye trembling saints n. 861 in The Church Hymn book 1872 (1772)

See also

- The Gospel Magazine which Toplady edited 1775–76

Bibliography

- Pollard, Arthur, "Augustus Toplady", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Toplady, Augustus, The Complete Works (Harrisonburg: Sprinkle Publications, 1987) ISBN 1-59442-078-5.

Notes

- The abridgement was not included in Wesley's "Collected Works" until 1872.

References

- "Sheltering in the Rock". Banner of Truth. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- Works of Augustus Toplady (Sprinkle Publications, Harrisonburg, VA [1794], 1987) p. 34

- Toplady, Works, vol. 1, p. 189, at Wrights, T (1911), Toplady (biography), p. 34.

- Toplady, Augustus (1837) [1794], The Works, London: J Chidley, pp. 409–16, 443–46, 518–39.

- Thomas, Keith (1984), Man and the Natural World: Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800, London: Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-014686-8.

- Linzey, Andrew; Regan, Tom, eds. (1989), Animals and Christianity: A Book of Readings, London: SPCK, ISBN 0-281-04373-6.

- Preece, Rod (2003), "Darwinism, Christianity and the Great Vivisection Debate", Journal of the History of Ideas, 63 (3): 399–419, doi:10.1353/jhi.2003.0040, S2CID 45323048.

- Zanchi, Girolamo, The Doctrine of Absolute Predestination Stated and Asserted, translated by Toplady, with a letter to John Wesley appended.

- Ella, George (2000), "8", A Debtor to Mercy Alone (biography).

- A Letter to the Rev Mr John Wesley; Relative to His Pretended Abridgement of Zanchius on Predestination Archived 6 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine (26 March 1770).

- Bayliss, Peter. "Rock of Ages". This England Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 October 2004. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 50.

- Bennett, Henry Leigh (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 57. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Pollard, Arthur. "Toplady, Augustus Montague (1740–1778)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27555. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

- Works by Augustus Toplady at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Augustus Toplady at Internet Archive

- Works by Augustus Toplady at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Augustus Toplady at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Bibliographic directory from Project Canterbury

- Psalms and Hymns for Public and Private Worship by Augustus Toplady (1776)

- Toplady and His Ministry at the Wayback Machine (archived 29 September 2007) by J. C. Ryle

- The story behind "Rock of Ages" and a brief biography

- Hymns by Augustus Montague Toplady

- Site with several of Toplady's controversial works

- Site with a detailed Toplady bibliography

- Lyrics and music in MIDI format