Antoninus Pius

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius (19 September 86 – 7 March 161) was Roman emperor from 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.[3]

| Antoninus Pius | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

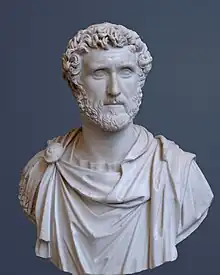

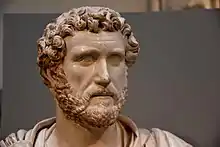

Bust in the Glyptothek, Munich | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | 11 July 138 – 7 March 161 | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Hadrian | ||||||||

| Successor | Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus | ||||||||

| Born | 19 September 86 Lanuvium, Italy | ||||||||

| Died | 7 March 161 (aged 74) Lorium, Italy | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | Annia Galeria Faustina | ||||||||

| Issue Detail |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Nerva–Antonine | ||||||||

| Father |

| ||||||||

| Mother |

| ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Roman religion | ||||||||

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nerva–Antonine dynasty (AD 96–192) | ||||||||||||||

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Family | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Succession | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Born into a senatorial family, Antoninus held various offices during the reign of Emperor Hadrian. He married Hadrian's niece Faustina, and Hadrian adopted him as his son and successor shortly before his death. Antoninus acquired the cognomen Pius after his accession to the throne, either because he compelled the Senate to deify his adoptive father,[4] or because he had saved senators sentenced to death by Hadrian in his later years.[5] His reign is notable for the peaceful state of the Empire, with no major revolts or military incursions during this time. A successful military campaign in southern Scotland early in his reign resulted in the construction of the Antonine Wall.

Antoninus was an effective administrator, leaving his successors a large surplus in the treasury, expanding free access to drinking water throughout the Empire, encouraging legal conformity, and facilitating the enfranchisement of freed slaves. He died of illness in 161 and was succeeded by his adopted sons Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus as co-emperors.

Early life

Childhood and family

Antoninus Pius was born Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionius Antoninus near Lanuvium (modern-day Lanuvio) in Italy to Titus Aurelius Fulvus, consul in 86, and wife Arria Fadilla.[3][6] The Aurelii Fulvi were an Aurelian family settled in Nemausus (modern Nîmes).[7] Titus Aurelius Fulvus was the son of a senator of the same name, who, as legate of Legio III Gallica, had supported Vespasian in his bid to the Imperial office and been rewarded with a suffect consulship, plus an ordinary one under Domitian in 85. The Aurelii Fulvi were therefore a relatively new senatorial family from Gallia Narbonensis whose rise to prominence was supported by the Flavians.[8] The link between Antoninus' family and their home province explains the increasing importance of the post of proconsul of Gallia Narbonensis during the late second century.[9]

Antoninus' father had no other children and died shortly after his 89 ordinary consulship. Antoninus was raised by his maternal grandfather Gnaeus Arrius Antoninus,[3] reputed by contemporaries to be a man of integrity and culture and a friend of Pliny the Younger.[10] The Arrii Antonini were an older senatorial family from Italy, very influential during Nerva's reign. Arria Fadilla, Antoninus' mother, married afterwards Publius Julius Lupus, suffect consul in 98; from that marriage came two daughters, Arria Lupula and Julia Fadilla.[11]

Marriage and children

Some time between 110 and 115, Antoninus married Annia Galeria Faustina the Elder.[12] They are believed to have enjoyed a happy marriage. Faustina was the daughter of consul Marcus Annius Verus (II)[3] and Rupilia Faustina (a step-sister to the Empress Vibia Sabina).[13][14] Faustina was a beautiful woman, and despite rumours about her character, it is clear that Antoninus cared for her deeply.[15]

Faustina bore Antoninus four children, two sons and two daughters.[16] They were:

- Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus (died before 138); his sepulchral inscription has been found at the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome.[17][18]

- Marcus Galerius Aurelius Antoninus (died before 138); his sepulchral inscription has been found at the Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome.[17][19] His name appears on a Greek Imperial coin.

- Aurelia Fadilla (died in 135); she married Lucius Plautius Lamia Silvanus, consul 145. She appeared to have no children with her husband; and her sepulchral inscription has been found in Italy.[20]

- Annia Galeria Faustina Minor or Faustina the Younger (between 125 and 130–175), a future Roman Empress, married her maternal cousin Marcus Aurelius in 146.[7]

When Faustina died in 141, Antoninus was greatly distressed.[21] In honour of her memory, he asked the Senate to deify her as a goddess, and authorised the construction of a temple to be built in the Roman Forum in her name, with priestesses serving in her temple.[22] He had various coins with her portrait struck in her honor. These coins were scripted "DIVA FAUSTINA" and were elaborately decorated. He further founded a charity, calling it Puellae Faustinianae or Girls of Faustina, which assisted destitute girls[12] of good family.[23] Finally, Antoninus created a new alimenta, a Roman welfare programme, as part of Cura Annonae.

The emperor never remarried. Instead, he lived with Galeria Lysistrate,[24] one of Faustina's freed women. Concubinage was a form of female companionship sometimes chosen by powerful men in Ancient Rome, especially widowers like Vespasian, and Marcus Aurelius. Their union could not produce any legitimate offspring who could threaten any heirs, such as those of Antoninus. Also, as one could not have a wife and an official concubine (or two concubines) at the same time, Antoninus avoided being pressed into a marriage with a noblewoman from another family. (Later, Marcus Aurelius would also reject the advances of his former fiancée Ceionia Fabia, Lucius Verus's sister, on the grounds of protecting his children from a stepmother, and took a concubine instead.)[25][26][27]

Favour with Hadrian

Having filled the offices of quaestor and praetor with more than usual success,[28] he obtained the consulship in 120[12] having as his colleague Lucius Catilius Severus.[29] He was next appointed by the Emperor Hadrian as one of the four proconsuls to administer Italia,[30] his district including Etruria, where he had estates.[31] He then greatly increased his reputation by his conduct as proconsul of Asia, probably during 134–135.[30]

He acquired much favor with Hadrian, who adopted him as his son and successor on 25 February 138,[32] after the death of his first adopted son Lucius Aelius,[33] on the condition that Antoninus would in turn adopt Marcus Annius Verus, the son of his wife's brother, and Lucius, son of Lucius Aelius, who afterwards became the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus.[12] He also adopted (briefly) the name Imperator Titus Aelius Caesar Antoninus, in preparation for his rule.[34] There seems to have been some opposition to Antoninus' appointment on the part of other potential claimants, among them his former consular colleague Lucius Catilius Severus, then prefect of the city. Nevertheless, Antoninus assumed power without opposition.[35]

Emperor

On his accession, Antoninus' name and style became Imperator Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pontifex Maximus. One of his first acts as Emperor was to persuade the Senate to grant divine honours to Hadrian, which they had at first refused;[36] his efforts to persuade the Senate to grant these honours is the most likely reason given for his title of Pius (dutiful in affection; compare pietas).[37] Two other reasons for this title are that he would support his aged father-in-law with his hand at Senate meetings, and that he had saved those men that Hadrian, during his period of ill-health, had condemned to death.[7]

Immediately after Hadrian's death, Antoninus approached Marcus and requested that his marriage arrangements be amended: Marcus' betrothal to Ceionia Fabia would be annulled, and he would be betrothed to Faustina, Antoninus' daughter, instead. Faustina's betrothal to Ceionia's brother Lucius Commodus, Marcus' future co-Emperor, would also have to be annulled. Marcus consented to Antoninus' proposal.[38][39]

Antoninus built temples, theaters, and mausoleums, promoted the arts and sciences, and bestowed honours and financial rewards upon the teachers of rhetoric and philosophy.[12] Antoninus made few initial changes when he became emperor, leaving intact as far as possible the arrangements instituted by Hadrian.[36] Epigraphical and prosopographical research has revealed that Antoninus' imperial ruling team centered around a group of closely knit senatorial families, most of them members of the priestly congregation for the cult of Hadrian, the sodales Hadrianales. According to the German historian H.G. Pflaum, prosopographical research of Antoninus' ruling team allows us to grasp the deeply conservative character of the ruling senatorial caste.[40]

He owned palatial villas at Lorium (Etruria) and Villa Magna (Latium).

Lack of warfare

.jpg.webp)

There are no records of any military related acts in his time in which he participated. One modern scholar has written "It is almost certain not only that at no time in his life did he ever see, let alone command, a Roman army, but that, throughout the twenty-three years of his reign, he never went within five hundred miles of a legion."[41]

His reign was the most peaceful in the entire history of the Principate,[42] notwithstanding the fact that there were several military disturbances in the Empire in his time. Such disturbances happened in Mauretania, where a senator was named as governor of Mauretania Tingitana in place of the usual equestrian procurator[43] and cavalry reinforcements from Pannonia were brought in,[44] towns such as Sala and Tipasa being fortified.[45] Similar disturbances took place in Judea, and amongst the Brigantes in Britannia; however, these were considered less serious than prior (and later) revolts among both.[42] It was however in Britain that Antoninus decided to follow a new, more aggressive path, with the appointment of a new governor in 139, Quintus Lollius Urbicus,[36] a native of Numidia and previously governor of Germania Inferior[46] as well as a new man.[47]

Under instructions from the emperor, Lollius undertook an invasion of southern Scotland, winning some significant victories, and constructing the Antonine Wall[48] from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. The wall, however, was soon gradually decommissioned during the mid-150s and eventually abandoned late during the reign (early 160s), for reasons that are still not quite clear.[49][50] Antonine's Wall is mentioned in just one literary source, Antoninus' biography in the Historia Augusta. Pausanias makes a brief and confused mention of a war in Britain. In one inscription honouring Antoninus, erected by Legio II Augusta, which participated in the building of the Wall, a relief showing four naked prisoners, one of them beheaded, seems to stand for some actual warfare.[51]

.JPG.webp)

Although Antonine's Wall was, in principle, much shorter (37 miles in length as opposed to 73), and at first sight more defensible than Hadrian's Wall, the additional area that it enclosed within the Empire was barren, with land use for grazing already in decay.[52] This meant that supply lines to the wall were strained enough such as the costs for maintaining the additional territory outweighed the benefits of doing so.[53] Also, in the absence of urban development and the ensuing Romanization process, the rear of the wall could not be lastingly pacified.[54]

It has been therefore speculated that the invasion of Lowland Scotland and the building of the wall had to do mostly with internal politics, that is, offering Antoninus an opportunity to gain some modicum of necessary military prestige at the start of his reign. Actually, the campaign in Britannia was followed by an Imperial salutation, that is, by Antoninus formally taking for the second (and last) time the title of Imperator in 142.[55] The fact that around the same time coins were struck announcing a victory in Britain points to Antoninus' need to publicise his achievements.[56] The orator Fronto was later to say that, although Antoninus bestowed the direction of the British campaign to others, he should be regarded as the helmsman who directed the voyage, whose glory, therefore, belonged to him.[57]

That this quest for some military achievement responded to an actual need is proved by the fact that, although generally peaceful, Antoninus' reign was not free from attempts at usurpation: Historia Augusta mentions two, made by the senators Cornelius Priscianus ("for disturbing the peace of Spain";[58] Priscianus had also been Lollius Urbicus' successor as governor of Britain) and Atilius Rufius Titianus (possibly a troublemaker already exiled under Hadrian[59]). Both attempts are confirmed by the Fasti Ostienses as well as by the erasing of Priscianus' name from an inscription.[60] In both cases, Antoninus was not in formal charge of the ensuing repression: Priscianus committed suicide and Titianus was found guilty by the Senate, with Antoninus abstaining from sequestering their families' properties.[61]

There were also some troubles in Dacia Inferior which required the granting of additional powers to the procurator governor and the dispatch of additional soldiers to the province.[49] On the northern Black Sea coast, the Greek city of Olbia was held against the Scythians.[63] Also during his reign the governor of Upper Germany, probably Caius Popillius Carus Pedo, built new fortifications in the Agri Decumates, advancing the Limes Germanicus fifteen miles forward in his province and neighboring Raetia.[64] In the East, Roman suzerainty over Armenia was retained by the choice in AD 140 of Arsacid scion Sohaemus as client king.[65]

Nevertheless, Antoninus was virtually unique among emperors in that he dealt with these crises without leaving Italy once during his reign,[66] but instead dealt with provincial matters of war and peace through their governors or through imperial letters to the cities such as Ephesus (of which some were publicly displayed). This style of government was highly praised by his contemporaries and by later generations.[67]

Antoninus was the last Roman Emperor recognised by the Indian Kingdoms, especially the Kushan Empire.[68] Raoul McLaughlin quotes Aurelius Victor as saying "The Indians, the Bactrians, and the Hyrcanians all sent ambassadors to Antoninus. They had all heard about the spirit of justice held by this great emperor, justice that was heightened by his handsome and grave countenance, and his slim and vigorous figure." Due to the outbreak of the Antonine epidemic and wars against northern Germanic tribes, the reign of Marcus Aurelius was forced to alter the focus of foreign policies, and matters relating to the Far East were increasingly abandoned in favour of those directly concerning the Empire's survival.[68]

Economy and administration

Antoninus was regarded as a skilled administrator and as a builder. In spite of an extensive building directive—the free access of the people of Rome to drinking water was expanded with the construction of aqueducts, not only in Rome but throughout the Empire, as well as bridges and roads—the emperor still managed to leave behind a sizable public treasury of around 2.7 billion sesterces. Rome would not witness another Emperor leaving his successor with a surplus for a long time, but this treasury was depleted almost immediately after Antoninus's reign due to the Antonine Plague brought back by soldiers after the Parthian victory.[69]

The Emperor also famously suspended the collection of taxes from multiple cities affected by natural disasters, such as when fires struck Rome and Narbona, and earthquakes affected Rhodes and the Province of Asia. He offered hefty financial grants for rebuilding and recovery of various Greek cities after two serious earthquakes: the first, circa 140, which affected mostly Rhodes and other islands; the second, in 152, which hit Cyzicus (where the huge and newly built Temple to Hadrian was destroyed[70]), Ephesus, and Smyrna. Antoninus' financial help earned him praise by Greek writers such as Aelius Aristides and Pausanias.[71] These cities received from Antoninus the usual honorific accolades, such as when he commanded that all governors of Asia should enter the province, when taking office, by way of Ephesus.[72] Ephesus was specially favoured by Antoninus, who confirmed and upheld its distinction of having two temples for the imperial cult (neocorate), therefore having first place in the list of imperial honor titles, surpassing both Smyrna and Pergamon.[73]

In his dealings with Greek-speaking cities, Antoninus followed the policy adopted by Hadrian of ingratiating himself with local elites, especially with local intellectuals: philosophers, teachers of literature, rhetoricians and physicians were explicitly exempted from any duties involving private spending for civic purposes, a privilege granted by Hadrian that Antoninus confirmed by means of an edict preserved in the Digest (27.1.6.8).[74] Antoninus also created a chair for the teaching of rhetoric in Athens.[75]

Antoninus was known as an avid observer of rites of religion and of formal celebrations, both Roman and foreign. He is known for having increasingly formalized the official cult offered to the Great Mother, which from his reign onwards included a bull sacrifice, a taurobolium, formerly only a private ritual, now being also performed for the sake of the Emperor's welfare.[76] Antoninus also offered patronage to the worship of Mithras, to whom he erected a temple in Ostia.[77] In 148, he presided over the celebrations of the 900th anniversary of the founding of Rome.

Legal reforms

.jpg.webp)

British Museum, London.

Antoninus tried to portray himself as a magistrate of the res publica, no matter how extended and ill-defined his competencies were. He is credited with the splitting of the imperial treasury, the fiscus. This splitting had to do with the division of imperial properties into two parts. Firstly, the fiscus itself, or patrimonium, meaning the properties of the "Crown", the hereditary properties of each succeeding person that sat on the throne, transmitted to his successors in office,[78] regardless of their previous membership in the imperial family.[79] Secondly, the res privata, the "private" properties tied to the personal maintenance of the Emperor and his family,[80] something like a Privy Purse. An anecdote in the Historia Augusta biography, where Antoninus replies to Faustina (who complained about his stinginess) that "we have gained an empire [and] lost even what we had before" possibly relates to Antoninus' actual concerns at the creation of the res privata.[81] While still a private citizen, Antoninus had increased his personal fortune greatly by means of various legacies, the consequence of his caring scrupulously for his relatives.[82] Also, Antoninus left behind him a reputation for stinginess and was probably determined not to leave his personal property to be "swallowed up by the demands of the imperial throne".[83]

The res privata lands could be sold and/or given away, while the patrimonium properties were regarded as public.[84] It was a way of pretending that the Imperial function—and most properties attached to it—was a public one, formally subject to the authority of the Senate and the Roman people.[85] That the distinction played no part in subsequent political history—that the personal power of the princeps absorbed his role as office-holder—proves that the autocratic logic of the imperial order had already subsumed the old republican institutions.[86]

Of the public transactions of this period there is only the scantiest of information, but, to judge by what is extant, those twenty-two years were not remarkably eventful in comparison to those before and after the reign.[10] However, Antoninus did take a great interest in the revision and practice of the law throughout the empire.[87] One of his chief concerns was to having local communities conform their legal procedures to existing Roman norms: in a case concerning repression of banditry by local police officers ("irenarchs", Greek for "peace keepers") in Asia Minor, Antoninus ordered that these officers should not treat suspects as already condemned, and also keep a detailed copy of their interrogations, to be used in the possibility of an appeal to the Roman governor.[88] Also, although Antoninus was not an innovator, he would not always follow the absolute letter of the law; rather he was driven by concerns over humanity and equality, and introduced into Roman law many important new principles based upon this notion.[87]

In this, the emperor was assisted by five chief lawyers: Lucius Fulvius Aburnius Valens, an author of legal treatises;[89] Lucius Ulpius Marcellus, a prolific writer; and three others.[87] Of these three, the most prominent was Lucius Volusius Maecianus, a former military officer turned by Antoninus into a civil procurator, and who, in view of his subsequent career (discovered on the basis of epigraphical and prosopographical research), was the Emperor's most important legal adviser.[90] Maecianus would eventually be chosen to occupy various prefectures (see below) as well as to conduct the legal studies of Marcus Aurelius. He was also the author of a large work on Fidei commissa (Testamentary Trusts). As a hallmark of the increased connection between jurists and the imperial government,[91] Antoninus' reign also saw the appearance of the Institutes of Gaius, an elementary legal textbook for beginners.[87]

.png.webp)

Antoninus passed measures to facilitate the enfranchisement of slaves.[92] Mostly, he favoured the principle of favor libertatis, giving the putative freedman the benefit of the doubt when the claim to freedom was not clearcut.[93] Also, he punished the killing of a slave by their master without previous trial[94] and determined that slaves could be forcibly sold to another master by a proconsul in cases of consistent mistreatment.[95] Antoninus upheld the enforcement of contracts for selling of female slaves forbidding their further employment in prostitution.[96] In criminal law, Antoninus introduced the important principle that accused persons are not to be treated as guilty before trial,[92] as in the case of the irenarchs (see above). It was to Antoninus that the Christian apologist Justin Martyr addressed his defense of the Christian faith, reminding him of his father's (Emperor Hadrian's) rule that accusations against Christians required proof.[97] Antoninus also asserted the principle that the trial was to be held, and the punishment inflicted, in the place where the crime had been committed. He mitigated the use of torture in examining slaves by certain limitations. Thus he prohibited the application of torture to children under fourteen years, though this rule had exceptions.[92] However, it must be stressed that Antoninus extended, by means of a rescript, the use of torture as a means of obtaining evidence to pecuniary cases, when it had been applied up until then only in criminal cases.[98] Also, already at the time torture of free men of low status (humiliores) had become legal, as proved by the fact that Antoninus exempted town councillors expressly from it, and also free men of high rank (honestiores) in general.[99]

One highlight during his reign occurred in 148, with the nine-hundredth anniversary of the foundation of Rome being celebrated by the hosting of magnificent games in Rome.[100] It lasted a number of days, and a host of exotic animals were killed, including elephants, giraffes, tigers, rhinoceroses, crocodiles and hippopotamuses. While this increased Antoninus's popularity, the frugal emperor had to debase the Roman currency. He decreased the silver purity of the denarius from 89% to 83.5, the actual silver weight dropping from 2.88 grams to 2.68 grams.[49][101]

Scholars name Antoninus Pius as the leading candidate for an individual identified as a friend of Rabbi Judah the Prince. According to the Talmud (Avodah Zarah 10a–b), Rabbi Judah was very wealthy and greatly revered in Rome. He had a close friendship with "Antoninus", possibly Antoninus Pius,[102] who would consult Rabbi Judah on various worldly and spiritual matters.

Diplomatic mission to China

The first group of people claiming to be an ambassadorial mission of Romans to China was recorded in 166 AD by the Hou Hanshu.[103] Harper (2017)[104] states that the embassy was likely to be a group of merchants, as many Roman merchants traveled to India and some might have gone beyond, while there are no records of official ambassadors of Rome travelling as far east. The group came to Emperor Huan of Han China and claimed to be an embassy from "Andun" (Chinese: 安敦 āndūn; for Anton-inus), "king of Daqin" (Rome).[105] As Antoninus Pius died in 161, leaving the empire to his adoptive son Marcus Aurelius (Antoninus), and the envoy arrived in 166, confusion remains about who sent the mission, given that both Emperors were named "Antoninus".[106][107][108] The Roman mission came from the south (therefore probably by sea), entering China by the frontier province of Jiaozhi at Rinan or Tonkin (present-day northern Vietnam). It brought presents of rhinoceros horns, ivory, and tortoise shell, probably acquired in South Asia.[103][109] The text specifically states that it was the first time there had been direct contact between the two countries.[103][110]

Furthermore, a piece of Republican-era Roman glassware has been found at a Western Han tomb in Guangzhou along the South China Sea, dated to the early 1st century BC.[111] Roman golden medallions made during the reign of Antoninus Pius and perhaps even Marcus Aurelius have been found at Óc Eo in southern Vietnam, then part of the Kingdom of Funan near the Chinese province of Jiaozhi.[112][113] This may have been the port city of Kattigara, described by Ptolemy (c. 150) as being visited by a Greek sailor named Alexander and lying beyond the Golden Chersonese (i.e., Malay Peninsula).[112][113] Roman coins from the reigns of Tiberius to Aurelian have been discovered in Xi'an, China (site of the Han capital Chang'an), although the significantly greater amount of Roman coins unearthed in India suggest the Roman maritime trade for purchasing Chinese silk was centered there, not in China or even the overland Silk Road running through ancient Iran.[114]

Death and legacy

.jpg.webp)

In 156, Antoninus Pius turned 70. He found it difficult to keep himself upright without stays. He started nibbling on dry bread to give him the strength to stay awake through his morning receptions.

Marcus Aurelius had already been created consul with Antoninus in 140, receiving the title of Caesar, i.e., heir apparent.[115] As Antoninus aged, Marcus took on more administrative duties. Marcus's administrative duties increased again after the death, in 156 or 157, of one of Antoninus' most trusted advisers, Marcus Gavius Maximus.

For twenty years, Gavius Maximus had been praetorian prefect, an office that was as much secretarial as military.[116][117] Gavius Maximus had been awarded with the consular insignia and the honours due a senator.[118] He had a reputation as a most strict disciplinarian (vir severissimus, according to Historia Augusta) and some fellow equestrian procurators held lasting grudges against him. A procurator named Gaius Censorius Niger died while Gavius Maximus was alive. In his will, Censorius Niger vilified Maximus, creating serious embarrassment for one of the heirs, the orator Fronto.[119]

Gavius Maximus' death initiated a change in the ruling team. It has been speculated that it was the legal adviser Lucius Volusius Maecianus who assumed the role of grey eminence. Maecianus was briefly Praefect of Egypt, and subsequently Praefectus annonae in Rome. If it was Maecianus who rose to prominence, he may have risen precisely in order to prepare the incoming — and unprecedented — joint succession.[120] In 160, Marcus and Lucius were designated joint consuls for the following year. Perhaps Antoninus was already ill; in any case, he died before the year was out, probably on 7 March.[125]

_01.jpg.webp)

Two days before his death, the biographer reports, Antoninus was at his ancestral estate at Lorium, in Etruria,[126][127] about twelve miles (19 km) from Rome.[128] He ate Alpine Gruyere cheese at dinner quite greedily. In the night he vomited; he had a fever the next day. The day after that, he summoned the imperial council, and passed the state and his daughter to Marcus. The emperor gave the keynote to his life in the last word that he uttered: when the tribune of the night-watch came to ask the password, he responded, "aequanimitas" (equanimity).[129] He then turned over, as if going to sleep, and died.[130][131] His death closed out the longest reign since Augustus (surpassing Tiberius by a couple of months).[126] His record for the second-longest reign would be unbeaten for 168 years, until 329 when it was surpassed by Constantine the Great.

Antoninus Pius' funeral ceremonies were, in the words of the biographer, "elaborate".[132] If his funeral followed the pattern of past funerals, his body would have been incinerated on a pyre at the Campus Martius, while his spirit would rise to the gods' home in the heavens. However, it seems that this was not the case: according to his Historia Augusta biography (which seems to reproduce an earlier, detailed report) Antoninus' body (and not his ashes) was buried in Hadrian's mausoleum. After a seven-day interval (justitium), Marcus and Lucius nominated their father for deification.[133] In contrast to their behaviour during Antoninus' campaign to deify Hadrian, the senate did not oppose the emperors' wishes. A flamen, or cultic priest, was appointed to minister the cult of the deified Antoninus, now Divus Antoninus.

A column was dedicated to Antoninus on the Campus Martius,[12] and the temple he had built in the Forum in 141 to his deified wife Faustina was rededicated to the deified Faustina and the deified Antoninus.[129] It survives as the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda.[134]

Historiography

.jpg.webp)

The only intact account of his life handed down to us is that of the Augustan History, an unreliable and mostly fabricated work. Nevertheless, it still contains information that is considered reasonably sound; for instance, it is the only source that mentions the erection of the Antonine Wall in Britain.[135] Antoninus is unique among Roman emperors in that he has no other biographies.

Antoninus in many ways was the ideal of the landed gentleman praised not only by ancient Romans, but also by later scholars of classical history, such as Edward Gibbon[136] or the author of the article on Antoninus Pius in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.[10]

A few months afterwards, on Hadrian's death, he was enthusiastically welcomed to the throne by the Roman people, who, for once, were not disappointed in their anticipation of a happy reign. For Antoninus came to his new office with simple tastes, kindly disposition, extensive experience, a well-trained intelligence and the sincerest desire for the welfare of his subjects. Instead of plundering to support his prodigality, he emptied his private treasury to assist distressed provinces and cities, and everywhere exercised rigid economy (hence the nickname κυμινοπριστης "cummin-splitter"). Instead of exaggerating into treason whatever was susceptible of unfavorable interpretation, he turned the very conspiracies that were formed against him into opportunities for demonstrating his clemency. Instead of stirring up persecution against the Christians, he extended to them the strong hand of his protection throughout the empire. Rather than give occasion to that oppression which he regarded as inseparable from an emperor's progress through his dominions, he was content to spend all the years of his reign in Rome, or its neighbourhood.[10]

Some historians have a less positive view of his reign. According to the historian J. B. Bury,

however estimable the man, Antoninus was hardly a great statesman. The rest which the Empire enjoyed under his auspices had been rendered possible through Hadrian's activity, and was not due to his own exertions; on the other hand, he carried the policy of peace at any price too far, and so entailed calamities on the state after his death. He not only had no originality or power of initiative, but he had not even the insight or boldness to work further on the new lines marked out by Hadrian.[137]

German historian Ernst Kornemann has had it in his Römische Geschichte [2 vols., ed. by H. Bengtson, Stuttgart 1954] that the reign of Antoninus comprised "a succession of grossly wasted opportunities", given the upheavals that were to come. There is more to this argument, given that the Parthians in the East were themselves soon to make no small amount of mischief after Antoninus' death. Kornemann's brief is that Antoninus might have waged preventive wars to head off these outsiders. Michael Grant agrees that it is possible that had Antoninus acted decisively sooner (it appears that, on his death bed, he was preparing a large-scale action against the Parthians), the Parthians might have been unable to choose their own time, but current evidence is not conclusive. Grant opines that Antoninus and his officers did act in a resolute manner dealing with frontier disturbances of his time, although conditions for long-lasting peace were not created. On the whole, according to Grant, Marcus Aurelius' eulogistic picture of Antoninus seems deserved, and Antoninus appears to have been a conservative and nationalistic (although he respected and followed Hadrian's example of Philhellenism moderately) Emperor who was not tainted by the blood of either citizen or foe, combined and maintained Numa Pompilius' good fortune, pacific dutifulness and religious scrupulousness, and whose laws removed anomalies and softened harshnesses.[138]

Krzysztof Ulanowski argues that the claims of military inability are exaggerated, considering that although the sources praise Antoninus' love for peace and his efforts "rather to defend, than enlarge the provinces", he could hardly be considered a pacifist, as shown by the conquest of the Lowlands, the building of the Antonine Wall and the expansion of Germania Superior. Ulanowski also praises Antoninus for being successful in deterrence by diplomatic means.[139]

Descendants

Although only one of his four children survived to adulthood, Antoninus came to be ancestor to four generations of prominent Romans, including the Emperor Commodus. Hans-Georg Pflaum has identified five direct descendants of Antoninus and Faustina who were consuls in the first half of the third century.[140]

- Marcus Aurelius Fulvus Antoninus (died before 138), died young without issue

- Marcus Galerius Aurelius Antoninus (died before 138), died young without issue

- Aurelia Fadilla (died in 135), who married Lucius Plautius Lamia Silvanus, suffect consul in 145;[141] no children known for certain.

- Annia Galeria Faustina the Younger (21 September between 125 and 130–175), had several children; those who had children were:[142]

- Annia Aurelia Galeria Lucilla (7 March 150–182?), whose children included:

- Annia Galeria Aurelia Faustina (151–?), whose children included:

- Tiberius Claudius Severus Proculus

- Empress Annia Faustina, Elagabalus' third wife

- Tiberius Claudius Severus Proculus

- Annia Aurelia Fadilla (159–after 211)

- Annia Cornificia Faustina Minor (160–213)

Nerva–Antonine family tree

| |

| Notes:

Except where otherwise noted, the notes below indicate that an individual's parentage is as shown in the above family tree.

| |

References:

|

References

- Salomies, O (2014). "Adoptive and Polyonymous Nomenclature in the Roman Empire – Some Addenda". In Caldelli, M. L.; Gregori, G. L. (eds.). Epigrafia e ordine senatorio, 30 anni dopo. Edizioni Quasar. pp. 492–493. ISBN 9788871405674.

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 492–493. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Bowman 2000, p. 150.

- Birley 2000, p. 54; Dio, 70:1:2.

- Birley 2000, p. 55; citing the Historia Augusta, Life of Hadrian 24.4.

- Harvey, Paul B. (2006). Religion in republican Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 134.

- Bury 1893, p. 523.

- Whitfield, Hugo Thomas Dupuis (2012). The rise of Nemausus from Augustus to Antoninus Pius: a prosopographical study of Nemausian senators and equestrians (PDF) (MA). Ontario: Queen's University. pp. 49–57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Gayraud, Michel (1970). "Le proconsulat de Narbonnaise sous le Haut-Empire". Revue des Études Anciennes. 72 (3–4): 344–363. doi:10.3406/rea.1970.3874. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Birley 2000, p. 242; Historia Augusta, Antoninus Pius 1:6.

- Weigel, Antoninus Pius

- Rupilius. Strachan stemma.

- Settipani, Christian (2000). Continuité gentilice et continuité familiale dans les familles sénatoriales romaines à l'époque impériale: mythe et réalité. Prosopographica et genealogica (in Italian). Vol. 2 (illustrated ed.). Unit for Prosopographical Research, Linacre College, University of Oxford. p. 278. ISBN 9781900934022.

- Vagi, David L. (2000). Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, C. 82 B.C. – A.D. 480: History. Taylor & Francis. p. 240. ISBN 9781579583163.

- Birley 2000, p. 34; Historia Augusta, Antoninus Pius 1:7.

- Magie, David, Historia Augusta (1921), Life of Antoninus Pius, Note 6

- CIL VI, 00988

- CIL VI, 00989

- Magie, David, Historia Augusta (1921), Life of Antoninus Pius, Note 7

- Bury 1893, p. 528.

- Birley 2000, p. 77; Historia Augusta, Antoninus Pius 6:7.

- Daucé, Fernand (1968). "Découverte à Rennes d'une pièce de Faustine jeune". Annales de Bretagne. 75 (1): 270–276. doi:10.3406/abpo.1968.2460. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Anise K. Strong: Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World

- Strong, Anise K. (2016). Prostitutes and Matrons in the Roman World. Cambridge University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9781107148758.

- Lind, Goran (2008). Common Law Marriage: A Legal Institution for Cohabitation. Oxford University Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780199710539.

- Birley, Anthony R (2012). Marcus Aurelius: A Biography. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 9781134695690.

- Traver, Andrew G., From polis to empire, the ancient world, c. 800 B.C. – A.D. 500, (2002) p. 33; Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 2:9

- E.E. Bryant, The Reign of Antoninus Pius.Cambridge University Press, 1895, pg.12

- Bowman 2000, p. 149.

- Bryant, p. 15

- Bowman 2000, p. 148.

- Bury 1893, p. 517.

- Cooley, p. 492.

- Grant, Michael, The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition, (1996), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-13814-0, ps. 10/11

- Bowman 2000, p. 151.

- Birley 2000, p. 55.

- HA Marcus 6.2; Verus 2.3–4

- Birley 2000, pp. 53–54.

- H.G. Pflaum, "Les prêtres du culte impérial sous le règne d'Antonin le Pieux". In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 111e année, N. 2, 1967. pp. 194–209. Available at Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 27 January 2016

- J. J. Wilkes, The Journal of Roman Studies, Volume LXXV 19book ISSN 0075-4358, p. 242.

- Bury 1893, p. 525.

- René Rebuffat, '"Enceintes urbaines et insécurité en Maurétanie Tingitane" In: Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Antiquité, tome 86, n°1. 1974. pp. 501–522. Available at Archived 4 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 26 December 2015

- Michel Christol, "L'armée des provinces pannoniennes et la pacification des révoltes maures sous Antonin le Pieux". In: Antiquités africaines, 17, 1981. pp. 133–141.

- Michael Grant, The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. Abingdon: Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-13814-0, page 17; Rebuffat "Enceintes urbaines"

- Salway, A History of Roman Britain. Oxford University Press: 2001, ISBN 0-19-280138-4, p. 149

- Birley, Anthony (2005), The Roman Government of Britain. Oxford U.P., ISBN 978-0-19-925237-4, p. 137

- Bowman 2000, p. 152.

- Bowman 2000, p. 155.

- David Colin Arthur Shotter, Roman Britain, Abingdon: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-31943-9, page 49

- Jean-Louis Voisin, "Les Romains, chasseurs de têtes". In: Du châtiment dans la cité. Supplices corporels et peine de mort dans le monde antique. Table ronde de Rome (9-11 novembre 1982) Rome : École Française de Rome, 1984. pp. 241–293. Available at Archived 2 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 14 January 2016

- W. E. Boyd (1984),"Environmental change and Iron Age land management in the area of the Antonine Wall, central Scotland: a summary".Glasgow Archaeological Journal, Volume 11 Issue 1, pp. 75–81

- Peter Spring, Great Walls and Linear Barriers. Barnsley: Pen & Sword, 2015, ISBN 978-1-84884-377-6, p. 75

- Edward Luttwak, The grand Strategy of the Roman Empire. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979, ISBN 0-8018-2158-4, p. 88

- David J. Breeze, Roman Frontiers in Britain. London: Bloomsbury, 2013, ISBN 978-1-8539-9698-6, p. 53

- Salway, 149

- Birley, Anthony (2012). Marcus Aurelius, London: Routledge, 2012, ISBN 0-415-17125-3, p. 61

- Simon Hornblower, Antony Spawforth, Esther Eidinow (2014): The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization. ISBN 978-0-1910-1676-9, entry "Antoninus Pius"

- Herbert W. Benario (1980), A Commentary on the Vita Hadriani in the Historia Augusta. Scholars Press, ISBN 978-0-891-30391-6, page 103

- Albino Garzetti, From Tiberius to the Antonines: A History of the Roman Empire AD 14-192. London: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 978-1-138-01920-1, page 447; Paul Veyne, L'Empire Gréco-Romain, Paris: Seuil, 2005, ISBN 2-02-057798-4, page 28, footnote 61; Salway, 149

- Marta García Morcillo, Las ventas por subasta en el mundo romano: la esfera privada. Edicions Universitat Barcelona, 2005, ISBN 84-475-3017-5, page 301

- Schlude, Jason M. (13 January 2020). Rome, Parthia, and the Politics of Peace: The Origins of War in the Ancient Middle East. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-351-13570-2.

- Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, ed., North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies. Leiden: Brill, 2001, ISBN 90-04-12041-6, page 425

- Birley 2000, p. 113.

- Rouben Paul Adalian, Historical Dictionary of Armenia, Lanham: Scarecrow, 2010, ISBN 978-0-8108-6096-4, entry "Arshakuni/Arsacid", p. 174

- Speidel, Michael P., Riding for Caesar: The Roman Emperors' Horse Guards, Harvard University Press, 1997, p. 50

- See Victor, 15:3

- McLaughlin, Raoul (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India and China. A&C Black. p. 131. ISBN 9781847252357.

- Allen, Timothy F. H.; Hoekstra, Thomas W.; Tainter, Joseph A. (2012). Supply-Side Sustainability. Columbia University Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780231504072.

- Barbara Burrell. Neokoroi: Greek Cities and Roman Emperors. Leiden: Brill, 2004, ISBN 90-04-12578-7, page 87

- E.E. Bryant, The Reign of Antoninus Pius. Cambridge University Press: 1895, pages 45/46 and 68.

- Conrad Gempf, ed., The Book of Acts in Its Graeco-Roman Setting. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1994, ISBN 0-85364-564-7, page 305

- Emmanuelle Collas-Heddeland, "Le culte impérial dans la compétition des titres sous le Haut-Empire. Une lettre d'Antonin aux Éphésiens". In: Revue des Études Grecques, tome 108, Juillet-décembre 1995. pp. 410–429. Available at Archived 3 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 January 2016; Edmund Thomas,(2007): Monumentality and the Roman Empire: Architecture in the Antonine Age. Oxford U. Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928863-2, page 133

- Philip A. Harland, ed., Greco-Roman Associations: Texts, translations and commentaries. II: North Coast of the Black Sea, Asia Minor . Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014, ISBN 978-3-11-034014-3, page 381

- Paul Graindor, "Antonin le Pieux et Athènes". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire, tome 6, fasc. 3–4, 1927. pp. 753–756. Available at Archived 3 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 January 2016

- Gary Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion: One Thousand Years of Religious History. London: Routledge, 2012, ISBN 978-0-415-52217-5, page 92

- Samuel Dill, Roman Society from Nero to Marcus Aurelius. Library of Alexandria, s.d.g.

- Oxford Classical Dictionary, London: 2012, ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8, entry "Patrimonium".

- After the death of Nero, the personal properties of the Julio-Claudian dynasty had been appropriated by the Flavians, and therefore turned into public properties: Carrié & Roussele, 586

- Carrié & Rousselle, 586

- The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 11: The High Empire, AD 70–192. Cambridge U.P., 2009, ISBN 9780521263351, page 150

- Edward Champlin, Final Judgments: Duty and Emotion in Roman Wills, 200 B.C. – A.D. 250. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991, ISBN 0-520-07103-4, page 98

- Birley 2000, p. 71.

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay. London: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 978-0-415-84054-5, page 49

- Heinz Bellen, "Die 'Verstaatlichung' des Privatvermögens der römische Kaiser". Hildegard Temporini, ed., Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, Berlin: De Gruyter, 1974, ISBN 3-11-004571-0, page 112

- Aloys Winterling, Politics and Society in Imperial Rome. Malden, MA: John Wiley & sons, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4051-7969-0, pages 73/75

- Bury 1893, p. 526.

- Clifford Ando, Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-7486-2050-0, page 91

- John Anthony Crook, Consilium Principis: Imperial Councils and Counsellors from Augustus to Diocletian. Cambridge U.P.: 1955, page 67

- A. Arthur Schiller, Roman Law: Mechanisms of Development. The Hague: Mouton, 1978, ISBN 90-279-7744-5, page 477

- George Mousourakis, Roman Law and the Origins of the Civil Law Tradition, Heidelberg: Springer, ISBN 978-3-319-12267-0, page 79

- Bury 1893, p. 527.

- Keith Bradley, Slavery and Society at Rome. Cambridge University Press: 1994, ISBN 9780521263351, page 162

- Aubert, Jean-Jacques. "L'esclave en droit romain ou l'impossible réification de l'homme". Esclavage et travail forcé, Cahiers de la Recherche sur les droits fondamentaux (CRDF). Vol. 10. 2012.

- Anastasia Serghidou, ed. Fear of slaves, fear of enslavement in the ancient Mediterranean. Presses Univ. Franche-Comté, 2007 ISBN 978-2-84867-169-7, page 159

- Jean-Michel Carrié & Aline Rousselle, L'Empire Romain en Mutation, des Sévères à Constantin, 192–337. Paris: Seuil 1999, ISBN 2-02-025819-6, page 290

- First Apology of Justin Martyr, Chapter LXVIII

- Digest, 48.18.9, as quoted by Edward Peters, Torture, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8122-1599-0, page 29

- Grant, 154/155.

- Bowman 2000, p. 154.

- Tulane University "Roman Currency of the Principate"

- A. Mischcon, Abodah Zara, p.10a Soncino, 1988. Mischcon cites various sources, "SJ Rappaport... is of opinion that our Antoninus is Antoninus Pius." Other opinions cited suggest "Antoninus" was Caracalla, Lucius Verus or Alexander Severus.

- For a full translation of that passage, see: Paul Halsall (2000) [1998]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham.edu. Fordham University. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- Harper, Kyle (2017). The Fate of Rome. Princeton, New Jersey, United States: Princeton University Press.

- "... 其王常欲通使于汉,而安息欲以汉缯彩与之交市,故遮阂不得自达。至桓帝延熹九年,大秦王安敦遣使自日南徼外献象牙、犀角、瑇瑁,始乃一通焉。其所表贡,并无珍异,疑传者过焉。" 《后汉书·西域传》

Translation:

"... The king of this state always wanted to enter into diplomatic relations with the Han. But Anxi wanted to trade with them in Han silk and so put obstacles in their way, so that they could never have direct relations [with Han]. This continued until the ninth year of the Yanxi (延熹) reign period of Emperor Huan (桓) (A.D. 166), when Andun 安敦, king of Da Qin, sent an envoy from beyond the frontier of Rinan (日南) who offered elephant tusk, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell. It was only then that for the first time communication was established [between the two states]." "Xiyu Zhuan" of the Hou Hanshu (ch. 88)

in YU, Taishan (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) (2013). "China and the Ancient Mediterranean World: A Survey of Ancient Chinese Sources". Sino-Platonic Papers. 242: 25–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.698.1744..

Chinese original: "Chinese Text Project Dictionary". ctext.org. - Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. p. 600. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G.; Leslie, D. D.; Gardiner, K. H. J. (1999). "The Roman Empire as Known to Han China". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (1): 71–79. doi:10.2307/605541. JSTOR 605541.

- Hill (2009), p. 27 and nn. 12.18 and 12.20.

- Hill (2009), p. 27.

- An, Jiayao (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China". In Juliano, Annette L.; Lerner, Judith A. (eds.). Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road. Turnhout: Brepols. p. 83. ISBN 2503521789.

- Young, Gary K. (2001). Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305. London & New York: Routledge. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0-415-24219-3.

- For further information on Oc Eo, see Osborne, Milton (2006) [first published 2000]. The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future (revised ed.). Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. pp. 24–25. ISBN 1-74114-893-6.

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire (2nd ed.). London & New York: Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6.

- Geoffrey William Adams, Marcus Aurelius in the Historia Augusta and Beyond. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, ISBN 978-0-7391-7638-2, pp. 74–75.

- Birley 2000, p. 112.

- Grant, The Antonines, 14

- Michael Petrus Josephus Van Den Hout, A Commentary on the Letters of M. Cornelius Fronto. Leiden: Brill, 199, ISBN 9004109579, p. 389

- Champlin, Final Judgments, 16

- Michel Christol, "Préfecture du prétoire et haute administration équestre à la fin du règne d'Antonin le Pieux et au début du règne de Marc Aurèle". In: Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz, 18, 2007. pp. 115–140. Available at Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 27 January 2016

- Graf, Fritz (2015). Roman Festivals in the Greek East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–90. ISBN 9781107092112.

- Hammond, M. (1938). The Tribunician Day during the Early Empire. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 15, p. 46.

- Istituto Italiano d'Arti Grafiche (1956). Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 24-25. p. 101.

- H. Temporini, W. Haase (1972). Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt: Principat. V. De Gruyter. p. 534. ISBN 9783110018851.

- IGRR I, 1509. The date is found in an inscription dedicated to Titus Flavius Xenion.[121] The Feriale Duranum 1.21., written half a century later, implies that his successors took power the day before: "Prid(ie) Non[is Ma]r[tis". However, and for some reason, most historians who cite the passage indicate that it occurred on 7 March (nones martis).[122][123][124] It's not clear whether the error comes from the authors or the digitized version. Either way, this is the universally accepted date.[10]

- Bowman 2000, p. 156.

- Victor, 15:7

- Victor, 15:7

- Bury 1893, p. 532.

- HA Antoninus Pius 12.4–8

- Birley 2000, p. 114.

- HA Marcus 7.10, tr. David Magie, cited in Birley 2000, pp. 118, 278 n.6.

- Robert Turcan, "Origines et sens de l'inhumation à l'époque impériale". In: Revue des Études Anciennes. Tome 60, 1958, n°3–4. pp. 323–347. Available at Archived 3 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 14 January 2016

- Birley 2000, p. 118.

- Historia Augusta, Life of Antoninus Pius 5:4

- Gibbon, Edward (2015). Delphi Complete Works of Edward Gibbon (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 125. ISBN 9781910630761.

- Bury 1893, p. 524.

- Grant, Michael (2016). The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. Routledge. pp. 14–23. ISBN 9781317972112.

- Ulanowski, Krzysztof (2016). The Religious Aspects of War in the Ancient Near East, Greece, and Rome: Ancient Warfare Series, Volume 1. BRILL. pp. 360–361. ISBN 9789004324763.

- Pflaum, "Les gendres de Marc-Aurèle" Archived 5 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Journal des savants (1961), pp. 28–41

- Ronald Syme, "Antonine Relatives: Ceionii and Vettuleni", Athenaeum, 35 (1957), p. 309

- Based on Table F, "The Children of Faustina II" in Birley 2000

Sources

- Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 70, English translation

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribu", English translation

- Historia Augusta, The Life of Antoninus Pius, English translation. Note that the Historia Augusta includes pseudohistorical elements.

- Secondary sources

- Weigel, Richard D. (2 August 2023). "Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138–161) De Imperatoribus Romanis".

- Bowman, Alan K. (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History: The High Empire, A.D. 70–192. Cambridge University Press.

- Birley, Anthony (2000). Marcus Aurelius. Routledge.

- Bury, J. B. (1893). A History of the Roman Empire from its Foundation to the Death of Marcus Aurelius. Harper.

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hüttl, W. (1936) [1933]. Antoninus Pius. Vol. I & II, Prag.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antoninus Pius". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–149. This source lists:

- Bossart-Mueller, Zur Geschichte des Kaisers A. (1868)

- Bryant, The Reign of Antonine (Cambridge Historical Essays, 1895)

- Lacour-Gayet, A. le Pieux et son Temps (1888)

- Watson, P. B. (1884). "ii". Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. London: New York, Harper. ISBN 9780836956672.

External links

- Itinerarium Prouinciarum Antonini Augusti: Vibius Sequester, de fluminum & aliarum..., 1550, at the National Library of Portugal