Flavian dynasty

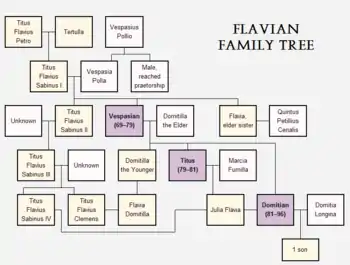

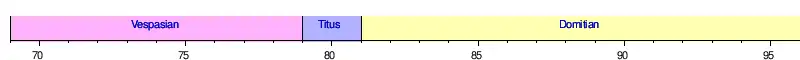

The Flavian dynasty ruled the Roman Empire between AD 69 and 96, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian (69–79), and his two sons Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96). The Flavians rose to power during the civil war of 69, known as the Year of the Four Emperors. After Galba and Otho died in quick succession, Vitellius became emperor in mid 69. His claim to the throne was quickly challenged by legions stationed in the Eastern provinces, who declared their commander Vespasian emperor in his place. The Second Battle of Bedriacum tilted the balance decisively in favour of the Flavian forces, who entered Rome on 20 December. The following day, the Roman Senate officially declared Vespasian emperor of the Roman Empire, thus commencing the Flavian dynasty. Although the dynasty proved to be short-lived, several significant historic, economic and military events took place during their reign.

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Flavian dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

|

69–79 AD |

||

|

79–81 AD |

||

|

81–96 AD |

||

| Family | ||

|

||

|

||

The reign of Titus was struck by multiple natural disasters, the most severe of which was the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79. The surrounding cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were completely buried under ash and lava. One year later, Rome was struck by fire and a plague. On the military front, the Flavian dynasty witnessed the siege and destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in 70, following the failed Jewish rebellion of 66. Substantial conquests were made in Great Britain under command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola between 77 and 83, while Domitian was unable to procure a decisive victory against King Decebalus in the war against the Dacians. In addition, the Empire strengthened its border defenses by expanding the fortifications along the Limes Germanicus.

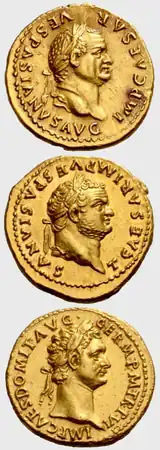

The Flavians also initiated economic and cultural reforms. Under Vespasian, new taxes were devised to restore the Empire's finances, while Domitian revalued the Roman coinage by increasing its silver content. A massive building programme was enacted by Titus, to celebrate the ascent of the Flavian dynasty, leaving multiple enduring landmarks in the city of Rome, the most spectacular of which was the Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum.

Flavian rule came to an end on 18 September 96, when Domitian was assassinated. He was succeeded by the longtime Flavian supporter and advisor Marcus Cocceius Nerva, who founded the long-lived Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

The Flavian dynasty was unique among the four dynasties of the Principate Era, in that it was only one man and his two sons, without any extended or adopted family.

History

Family history

Decades of civil war during the 1st century BC had contributed greatly to the demise of the old aristocracy of Rome, which was gradually replaced in prominence by a new Italian nobility during the early part of the 1st century AD.[1] One such family were the Flavians, or gens Flavia, which rose from relative obscurity to prominence in just four generations, acquiring wealth and status under the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Vespasian's grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, had served as a centurion under Pompey during Caesar's Civil War. His military career ended in disgrace when he fled the battlefield at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC.[2] Nevertheless, Petro managed to improve his status by marrying the extremely wealthy Tertulla, whose fortune guaranteed the upward mobility of Petro's son Titus Flavius Sabinus I.[3] Sabinus himself amassed further wealth and possible equestrian status through his services as tax collector in Asia and banker in Helvetia (modern Switzerland). By marrying Vespasia Polla he allied himself to the more prestigious patrician gens Vespasia, ensuring the elevation of his sons Titus Flavius Sabinus II and Vespasian to the senatorial rank.[3]

Around 38 AD, Vespasian married Domitilla the Elder, the daughter of an equestrian from Ferentium. They had two sons, Titus Flavius Vespasianus (born in 39) and Titus Flavius Domitianus (born in 51), and a daughter, Domitilla (born in 45).[4] Domitilla the Elder died before Vespasian became emperor. Thereafter his mistress Caenis was his wife in all but name until she died in 74.[5] The political career of Vespasian included the offices of quaestor, aedile and praetor, and culminated with a consulship in 51, the year Domitian was born. As a military commander, he gained early renown by participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43.[6] Nevertheless, ancient sources allege poverty for the Flavian family at the time of Domitian's upbringing,[7] even claiming Vespasian had fallen into disrepute under the emperors Caligula (37–41) and Nero (54–68).[8] Modern history has refuted these claims, suggesting these stories were later circulated under Flavian rule as part of a propaganda campaign to diminish success under the less reputable Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and maximize achievements under Emperor Claudius (41–54) and his son Britannicus.[9] By all appearances, imperial favour for the Flavians was high throughout the 40s and 60s. While Titus received a court education in the company of Britannicus, Vespasian pursued a successful political and military career. Following a prolonged period of retirement during the 50s, he returned to public office under Nero, serving as proconsul of the Africa province in 63, and accompanying the emperor during an official tour of Greece in 66.[10]

From c. 57 to 59, Titus was a military tribune in Germania, and later served in Britannia. His first wife, Arrecina Tertulla, died two years after their marriage, in 65.[11] Titus then took a new wife of a more distinguished family, Marcia Furnilla. However, Marcia's family was closely linked to the opposition to Emperor Nero. Her uncle Barea Soranus and his daughter Servilia were among those who were killed after the failed Pisonian conspiracy of 65.[12] Some modern historians theorize that Titus divorced his wife because of her family's connection to the conspiracy.[13][14] He never remarried. Titus appears to have had multiple daughters, at least one of them by Marcia Furnilla.[15] The only one known to have survived to adulthood was Julia Flavia, perhaps Titus's child by Arrecina, whose mother was also named Julia.[15] During this period Titus also practiced law and attained the rank of quaestor.[16]

In 66, the Jews of the Judaea Province revolted against the Roman Empire. Cestius Gallus, the legate of Syria, was forced to retreat from Jerusalem and defeated at the battle of Beth-Horon.[17] The pro-Roman king Agrippa II and his sister Berenice fled the city to Galilee where they later gave themselves up to the Romans. Nero appointed Vespasian to put down the rebellion, and dispatched him to the region at once with the fifth and tenth legions.[18][19] He was later joined by Titus at Ptolemais, bringing with him the fifteenth legion.[20] With a strength of 60,000 professional soldiers, the Romans quickly swept across Galilee, and by 68 marched on Jerusalem.[20]

Rise to power

On 9 June 68, amidst the growing opposition of the Senate and the army, Nero committed suicide, and with him the Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end. Chaos ensued, leading to a year of brutal civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors, during which the four most influential generals in the Roman Empire—Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian—successively vied for the imperial power. News of Nero's death reached Vespasian as he was preparing to besiege the city of Jerusalem. Almost simultaneously the Senate had declared Galba, then governor of Hispania Tarraconensis (modern Spain), as Emperor of Rome. Rather than continue his campaign, Vespasian decided to await further orders and send Titus to greet the new Emperor.[21] Before reaching Italy, however, Titus learnt that Galba had been murdered and replaced by Otho, the governor of Lusitania (modern Portugal). At the same time, Vitellius and his armies in Germania had risen in revolt, and prepared to march on Rome, intent on overthrowing Otho. Not wanting to risk being taken hostage by one side or the other, Titus abandoned the journey to Rome and rejoined his father in Judaea.[22]

Otho and Vitellius realised the potential threat posed by the Flavian faction. With four legions at his disposal, Vespasian commanded a strength of nearly 80,000 soldiers. His position in Judaea further granted him the advantage of being nearest to the vital province of Egypt, which controlled the grain supply to Rome. His brother, Titus Flavius Sabinus II, as city prefect, commanded the entire city garrison of Rome.[14] Tensions among the Flavian troops ran high, but as long as Galba and Otho remained in power, Vespasian refused to take action.[23] When Otho was defeated by Vitellius at the First Battle of Bedriacum, however, the armies in Judaea and Egypt took matters into their own hands and declared Vespasian emperor on 1 July 69.[24] Vespasian accepted, and entered an alliance with Gaius Licinius Mucianus, the governor of Syria, against Vitellius.[24] A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome under the command of Mucianus, while Vespasian himself traveled to Alexandria, leaving Titus in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion.[25]

In Rome, meanwhile, Domitian was placed under house arrest by Vitellius, as a safeguard against future Flavian aggression.[26] Support for the old emperor was waning, however, as more legions throughout the empire pledged their allegiance to Vespasian. On 24 October 69 the forces of Vitellius and Vespasian clashed at the Second Battle of Bedriacum, which ended in a crushing defeat for the armies of Vitellius.[27] In despair, he attempted to negotiate a surrender. Terms of peace, including a voluntary abdication, were agreed upon with Titus Flavius Sabinus II,[28] but the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard—the imperial bodyguard—considered such a resignation disgraceful, and prevented Vitellius from carrying out the treaty.[29] On the morning of 18 December, the emperor appeared to deposit the imperial insignia at the Temple of Concord, but at the last minute retraced his steps to the imperial palace. In the confusion, the leading men of the state gathered at Sabinus' house, proclaiming Vespasian Emperor, but the multitude dispersed when Vitellian cohorts clashed with the armed escort of Sabinus, who was forced to retreat to the Capitoline Hill.[30] During the night, he was joined by his relatives, including Domitian. The armies of Mucianus were nearing Rome, but the besieged Flavian party did not hold out for longer than a day. On 19 December, Vitellianists burst onto the Capitol, and in the resulting skirmish, Sabinus was captured and executed. Domitian himself managed to escape by disguising himself as a worshipper of Isis, and spent the night in safety with one of his father's supporters.[30] By the afternoon of 20 December, Vitellius was dead, his armies having been defeated by the Flavian legions. With nothing more to be feared from the enemy, Domitian came forward to meet the invading forces; he was universally saluted by the title of Caesar, and the mass of troops conducted him to his father's house.[30] The following day, 21 December, the Senate proclaimed Vespasian emperor of the Roman Empire.[31]

Although the war had officially ended, a state of anarchy and lawlessness pervaded in the first days following the demise of Vitellius. Order was properly restored by Mucianus in early 70, who headed an interim government with Domitian as the representative of the Flavian family in the Senate.[30] Upon receiving the tidings of his rival's defeat and death at Alexandria, the new Emperor at once forwarded supplies of urgently needed grain to Rome, along with an edict or a declaration of policy, in which he gave assurance of an entire reversal of the laws of Nero, especially those relating to treason. In early 70, Vespasian was still in Egypt, however, continuing to consolidate support from the Egyptians before departing.[32] By the end of 70, he finally returned to Rome, and was properly installed as Emperor.

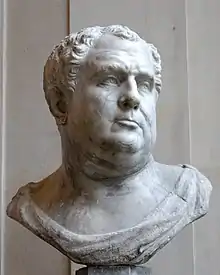

Vespasian (69–79)

Little factual information survives about Vespasian's government during the ten years he was Emperor. Vespasian spent his first year as a ruler in Egypt, during which the administration of the empire was given to Mucianus, aided by Vespasian's son Domitian. Modern historians believe that Vespasian remained there in order to consolidate support from the Egyptians.[33] In mid-70, Vespasian first came to Rome and immediately embarked on a widespread propaganda campaign to consolidate his power and promote the new dynasty. His reign is best known for financial reforms following the demise of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, such as the institution of the tax on urinals, and the numerous military campaigns fought during the 70s. The most significant of these was the First Jewish-Roman War, which ended in the destruction of the city of Jerusalem by Titus. In addition, Vespasian faced several uprisings in Egypt, Gaul and Germania, and reportedly survived several conspiracies against him.[34] Vespasian helped rebuild Rome after the civil war, adding a temple to peace and beginning construction of the Flavian Amphitheatre, better known as the Colosseum.[35] Vespasian died of natural causes on 23 June 79, and was immediately succeeded by his eldest son Titus.[36] The ancient historians that lived through the period such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus and Pliny the Elder speak well of Vespasian while condemning the emperors that came before him.[37]

Titus (79–81)

Despite initial concerns over his character, Titus ruled to great acclaim following the death of Vespasian on 23 June 79, and was considered a good emperor by Suetonius and other contemporary historians.[38] In this role he is best known for his public building program in Rome, and completing the construction of the Colosseum in 80,[39] but also for his generosity in relieving the suffering caused by two disasters, the Mount Vesuvius eruption of 79, and the fire of Rome of 80.[40] Titus continued his father's efforts to promote the Flavian dynasty. He revived practice of the imperial cult, deified his father, and laid foundations for what would later become the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, which was finished by Domitian.[41][42] After barely two years in office, Titus unexpectedly died of a fever on 13 September 81, and was deified by the Roman Senate.[43]

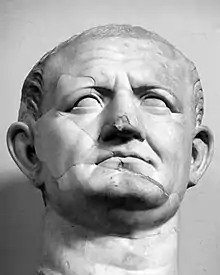

Domitian (81–96)

Domitian was declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard the day after Titus' death, commencing a reign which lasted more than fifteen years—longer than any man who had governed Rome since Tiberius. Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing the Roman coinage,[44] expanded the border defenses of the Empire,[45] and initiated a massive building programme to restore the damaged city of Rome.[46] In Britain, Gnaeus Julius Agricola expanded the Roman Empire as far as modern day Scotland,[47] but in Dacia, Domitian was unable to procure a decisive victory in the war against the Dacians.[48] On 18 September 96, Domitian was assassinated by court officials, and with him the Flavian dynasty came to an end. The same day, he was succeeded by his friend and advisor Nerva, who founded the long-lasting Nervan-Antonian dynasty. Domitian's memory was condemned to oblivion by the Roman Senate, with which he had a notoriously difficult relationship throughout his reign. Senatorial authors such as Tacitus, Pliny the Younger and Suetonius published histories after his death, propagating the view of Domitian as a cruel and paranoid tyrant. Modern history has rejected these views, instead characterising Domitian as a ruthless but efficient autocrat, whose cultural, economic and political programme provided the foundation for the Principate of the peaceful 2nd century. His successors Nerva and Trajan were less restrictive, but in reality their policies differed little from Domitian's.[49]

Administration

Government

Since the fall of the Republic, the authority of the Roman Senate had largely eroded under the quasi-monarchical system of government established by Augustus, known as the Principate. The Principate allowed the existence of a de facto dictatorial regime, while maintaining the formal framework of the Roman Republic.[50] Most Emperors upheld the public facade of democracy, and in return the Senate implicitly acknowledged the Emperor's status as a de facto monarch.[51] The civil war of 69 had made it abundantly clear that real power in the Empire lay with control over the army. By the time Vespasian was proclaimed emperor in Rome, any hope of restoring the Republic had long dissipated.

The Flavian approach to government was one of both implicit and explicit exclusion. When Vespasian returned to Rome in mid-70, he immediately embarked on a series of efforts to consolidate his power and prevent future revolts. He offered gifts to the military and dismissed or punished those soldiers loyal to Vitellius.[52] He also restructured the Senatorial and Equestrian orders, removing his enemies and adding his allies. Executive control was largely distributed among members of his family. Non-Flavians were virtually excluded from important public offices, even those who had been among Vespasian's earliest supporters during the civil war. Mucianus slowly disappears from the historical records during this time, and it is believed he died sometime between 75 and 77.[53] That it was Vespasian's intention to found a long-lasting dynasty to govern the Roman Empire was most evident in the powers he conferred upon his eldest son Titus. Titus shared tribunician power with his father, received seven consulships, the censorship, and perhaps most remarkably, was given command of the Praetorian Guard.[54] Because Titus effectively acted as co-emperor with his father, no abrupt change in Flavian policy occurred during his brief reign from 79 until 81.[55]

Domitian's approach to government was less subtle than his father and brother. Once Emperor, he quickly dispensed with the Republican facade[56] and transformed his government more or less formally into the divine monarchy he believed it to be. By moving the centre of power to the imperial court, Domitian openly rendered the Senate's powers obsolete. He became personally involved in all branches of the administration: edicts were issued governing the smallest details of everyday life and law, while taxation and public morals were rigidly enforced.[57] Nevertheless, Domitian did make concessions toward senatorial opinion. Whereas his father and brother had virtually excluded non-Flavians from public office, Domitian rarely favoured his own family members in the distribution of strategic posts, admitting a surprisingly large number of provincials and potential opponents to the consulship,[58] and assigning men of the equestrian order to run the imperial bureaucracy.[59]

Financial reforms

One of Vespasian's first acts as Emperor was to enforce a tax reform to restore the Empire's depleted treasury. After Vespasian arrived in Rome in mid-70, Mucianus continued to press Vespasian to collect as many taxes as possible,[60] renewing old ones and instituting new ones. Mucianus and Vespasian increased the tribute of the provinces, and kept a watchful eye upon the treasury officials. The Latin proverb "Pecunia non olet" ("Money does not smell") may have been created when he had introduced a urine tax on public toilets.

Upon his accession, Domitian revalued the Roman coinage to the standard of Augustus, increasing the silver content of the denarius by 12%. An imminent crisis in 85, however, forced a devaluation to the Neronian standard of 65,[61] but this was still higher than the level which Vespasian and Titus had maintained during their reign, and Domitian's rigorous taxation policy ensured that this standard was sustained for the following eleven years.[61] Coin types from this era display a highly consistent degree of quality, including meticulous attention to Domitian's titulature, and exceptionally refined artwork on the reverse portraits.[61]

Jones estimates Domitian's annual income at more than 1,200 million sestertii, of which over one-third would presumably have been spent on maintaining the Roman army.[62] The other major area of expenditure encompassed the vast reconstruction programme carried out on the city of Rome itself.

Challenges

Military activity

The most significant military campaign undertaken during the Flavian period was the siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 by Titus. The destruction of the city was the culmination of the Roman campaign in Judaea following the Jewish uprising of 66. The Second Temple was completely demolished, after which Titus's soldiers proclaimed him imperator in honor of the victory.[63] Jerusalem was sacked and much of the population killed or dispersed. Josephus claims that 1,100,000 people were killed during the siege, of which a majority were Jewish.[64] 97,000 were captured and enslaved, including Simon Bar Giora and John of Giscala.[64] Many fled to areas around the Mediterranean. Titus reportedly refused to accept a wreath of victory, and instead "disclaimed any such honor to himself, saying that it was not himself that had accomplished this exploit, but that he had merely lent his arms to God."[65] Upon his return to Rome in 71, Titus was awarded a triumph.[66] Accompanied by Vespasian and Domitian, he rode into the city, enthusiastically saluted by the Roman populace and preceded by a lavish parade containing treasures and captives from the war. Josephus describes a procession with large amounts of gold and silver carried along the route, followed by elaborate re-enactments of the war, Jewish prisoners, and finally the treasures taken from the Temple of Jerusalem, including the Menorah and the Torah.[67] Leaders of the resistance were executed in the Forum, after which the procession closed with religious sacrifices at the Temple of Jupiter.[68] The triumphal Arch of Titus, which stands at one entrance to the Forum, memorializes the victory of Titus.

The conquest of Britain continued under command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who expanded the Roman Empire as far as Caledonia, or modern day Scotland, between 77 and 84. In 82 Agricola crossed an unidentified body of water and defeated peoples unknown to the Romans until then.[69] He fortified the coast facing Ireland, and Tacitus recalls that his father-in-law often claimed the island could be conquered with a single legion and a few auxiliaries.[70] He had given refuge to an exiled Irish king whom he hoped he might use as the excuse for conquest. This conquest never happened, but some historians believe that the crossing referred to was in fact a small-scale exploratory or punitive expedition to Ireland.[71] The following year Agricola raised a fleet and pushed beyond the Forth into Caledonia. To aid the advance, an expansive legionary fortress was constructed at Inchtuthil.[70] In the summer of 84, Agricola faced the armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus, at the Battle of Mons Graupius.[72] Although the Romans inflicted heavy losses on the Caledonians, two-thirds of their army managed to escape and hide in the Scottish marshes and Highlands, ultimately preventing Agricola from bringing the entire British island under his control.[70]

The military campaigns undertaken during Domitian's reign were usually defensive in nature, as the Emperor rejected the idea of expansionist warfare.[73] His most significant military contribution was the development of the Limes Germanicus, which encompassed a vast network of roads, forts and watchtowers constructed along the Rhine river to defend the Empire.[74] Nevertheless, several important wars were fought in Gaul, against the Chatti, and across the Danube frontier against the Suebi, the Sarmatians, and the Dacians. Led by King Decebalus, the Dacians invaded the province of Moesia around 84 or 85, wreaking considerable havoc and killing the Moesian governor, Oppius Sabinus.[75] Domitian immediately launched a counteroffensive, which resulted in the destruction of a legion during an ill-fated expedition into Dacia. Their commander, Cornelius Fuscus, was killed, and the battle standard of the Praetorian Guard lost.[76] In 87, the Romans invaded Dacia once more, this time under command of Tettius Julianus, and finally managed to defeat Decebalus late in 88, at the same site where Fuscus had previously been killed.[77] An attack on Dacia's capital was abandoned, however, when a crisis arose on the German frontier, forcing Domitian to sign a peace treaty with Decebalus which was severely criticized by contemporary authors.[78] For the remainder of Domitian's reign Dacia remained a relatively peaceful client kingdom, but Decebalus used the Roman money to fortify his defenses, and continued to defy Rome. It was not until the reign of Trajan, in 106, that a decisive victory against Decebalus was procured. Again, the Roman army sustained heavy losses, but Trajan succeeded in capturing Sarmizegetusa and, importantly, annexed the gold and silver mines of Dacia.[79]

Natural disasters

Although his administration was marked by a relative absence of major military or political conflicts, Titus faced a number of major disasters during his brief reign. On 24 August 79, barely two months after his accession, Mount Vesuvius erupted,[80] resulting in the almost complete destruction of life and property in the cities and resort communities around the Bay of Naples. The cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were buried under metres of stone and lava,[81] killing thousands of citizens.[82] Titus appointed two ex-consuls to organise and coordinate the relief effort, while personally donating large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to aid the victims of the volcano.[83] Additionally, he visited Pompeii once after the eruption and again the following year.[84] The city was lost for nearly 1700 years before its accidental rediscovery in 1748. Since then, its excavation has provided an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city at the height of the Roman Empire, frozen at the moment it was buried. The Forum, the baths, many houses, and some out-of-town villas like the Villa of the Mysteries remain surprisingly well preserved. Today, it is one of the most popular tourist attractions of Italy and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. On-going excavations reveal new insights into Roman history and culture.

During Titus' second visit to the disaster area, a fire struck Rome which lasted for three days.[83][84] Although the extent of the damage was not as disastrous as during the Great Fire of 64, crucially sparing the many districts of insulae, Cassius Dio records a long list of important public buildings that were destroyed, including Agrippa's Pantheon, the Temple of Jupiter, the Diribitorium, parts of Pompey's Theatre and the Saepta Julia among others.[84] Once again, Titus personally compensated for the damaged regions.[84] According to Suetonius, a plague similarly struck during the fire.[83] The nature of the disease, however, as well as the death toll, are unknown.

Conspiracies

Suetonius claims that Vespasian was continuously met with conspiracies against him.[34] Only one conspiracy is known specifically. In 78 or 79, Eprius Marcellus and Aulus Caecina Alienus attempted to incite the Praetorian Guard to mutiny against Vespasian, but the conspiracy was thwarted by Titus.[85] According to the historian John Crook, however, the alleged conspiracy was in fact a calculated plot by the Flavian faction to remove members of the opposition tied to Mucianus, with the mutinous address found on Caecina's body a forgery by Titus.[86] When faced with real conspiracies however, Vespasian and Titus treated their enemies with lenience. "I will not kill a dog that barks at me," were words expressing the temper of Vespasian, while Titus once demonstrated his generosity as Emperor by inviting men who were suspected of aspiring to the throne to dinner, rewarding them with gifts and allowing them to be seated next to him at the games.[87]

Domitian appears to have met with several conspiracies during his reign, one of which led to his eventual assassination in 96. The first significant revolt arose on 1 January 89, when the governor of Germania Superior, Lucius Antonius Saturninus, and his two legions at Mainz, Legio XIV Gemina and Legio XXI Rapax, rebelled against the Roman Empire with the aid of the Chatti.[88] The precise cause for the rebellion is uncertain, although it appears to have been planned well in advance. The senatorial officers may have disapproved of Domitian's military strategies, such as his decision to fortify the German frontier rather than attack, his recent retreat from Britain, and finally the disgraceful policy of appeasement towards Decebalus.[89] At any rate, the uprising was strictly confined to Saturninus' province, and quickly detected once the rumour spread across the neighbouring provinces. The governor of Germania Inferior, Lappius Maximus, moved to the region at once, assisted by the procurator of Rhaetia, Titus Flavius Norbanus. From Spain, Trajan was summoned, whilst Domitian himself came from Rome with the Praetorian Guard. By a stroke of luck, a thaw prevented the Chatti from crossing the Rhine and coming to Saturninus' aid.[90] Within twenty-four days the rebellion was crushed, and its leaders at Mainz savagely punished. The mutinous legions were sent to the front in Illyricum, while those who had assisted in their defeat were duly rewarded.[91]

Both Tacitus and Suetonius speak of escalating persecutions toward the end of Domitian's reign, identifying a point of sharp increase around 93, or sometime after the failed revolt of Saturninus in 89.[92][93] At least twenty senatorial opponents were executed,[94] including Domitia Longina's former husband Lucius Aelius Lamia Plautius Aelianus and three of Domitian's own family members, Titus Flavius Sabinus IV, Titus Flavius Clemens and Marcus Arrecinus Clemens.[95] Some of these men were executed as early as 83 or 85, however, lending little credit to Tacitus' notion of a "reign of terror" late in Domitian's reign. According to Suetonius, some were convicted for corruption or treason, others on trivial charges, which Domitian justified through his suspicion.

Flavian culture

Propaganda

Since the reign of Tiberius, the rulers of the Julio-Claudian dynasty had legitimized their power through adopted-line descent from Augustus and Julius Caesar. Vespasian could no longer claim such a relation, however. Therefore, a massive propaganda campaign was initiated to justify Flavian rule as having been predetermined through divine providence.[96] At the same time, Flavian propaganda emphasised Vespasian's role as a bringer of peace following the crisis of 69. Nearly one-third of all coins minted in Rome under Vespasian celebrated military victory or peace,[97] while the word vindex was removed from coins as to not remind the public of rebellious Vindex. Construction projects bore inscriptions praising Vespasian and condemning previous emperors,[98] and a Temple of Peace was constructed in the forum.[35]

The Flavians also controlled public opinion through literature. Vespasian approved histories written under his reign, assuring biases against him were removed,[99] while also giving financial rewards to contemporary writers.[100] The ancient historians that lived through the period such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus and Pliny the Elder speak suspiciously well of Vespasian while condemning the emperors that came before him.[37] Tacitus admits that his status was elevated by Vespasian, Josephus identifies Vespasian as a patron and savior, and Pliny dedicated his Natural History to Vespasian's son, Titus.[101] Those that spoke against Vespasian were punished. A number of Stoic philosophers were accused of corrupting students with inappropriate teachings and were expelled from Rome.[102] Helvidius Priscus, a pro-Republic philosopher, was executed for his teachings.[103]

Titus and Domitian also revived the practice of the imperial cult, which had fallen somewhat out of use under Vespasian. Significantly, Domitian's first act as Emperor was the deification of his brother Titus. Upon their deaths, his infant son, and niece Julia Flavia, were likewise enrolled among the gods. To foster the worship of the imperial family, Domitian erected a dynastic mausoleum on the site of Vespasian's former house on the Quirinal,[104] and completed the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, a shrine dedicated to the worship of his deified father and brother.[105] To memorialize the military triumphs of the Flavian family, he ordered the construction of the Templum Divorum and the Templum Fortuna Redux, and completed the Arch of Titus. In order to further justify the divine nature of Flavian rule, Domitian also emphasized connections with the chief deity Jupiter,[106] most significantly through the restoration of the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill.

Construction

The Flavian dynasty is perhaps best known for its vast construction programme in the city of Rome, intended to restore the capital from the damage it had suffered during the Great Fire of 64, and the civil war of 69. Vespasian added the Temple of Peace and the Temple to the Deified Claudius.[107] In 75 a colossal statue of Apollo, begun under Nero as a statue of himself, was finished on Vespasian's orders, and he also dedicated a stage of the theater of Marcellus. Construction of the Flavian Amphitheatre, presently better known as the Colosseum (probably after the nearby statue), was begun in 70 under Vespasian and finally completed in 80 under Titus.[108] In addition to providing spectacular entertainments to the Roman populace, the building was conceived as a gigantic triumphal monument to commemorate the military achievements of the Flavians during the Jewish wars.[109] Adjacent to the amphitheatre, within the precinct of Nero's Golden House, Titus also ordered the construction of a new public bath-house, which was to bear his name.[110] Construction of this building was hastily finished to coincide with the completion of the Flavian Amphitheatre.[111]

The bulk of the Flavian construction projects were carried out during the reign of Domitian, who spent lavishly to restore and embellish the city of Rome. Much more than a renovation project, however, Domitian's building programme was intended to be the crowning achievement of an Empire-wide cultural renaissance. Around fifty structures were erected, restored or completed, a number second only to the amount erected under Augustus.[112] Among the most important new structures were an Odeum, a Stadium, and an expansive palace on the Palatine Hill, known as the Flavian Palace, which was designed by Domitian's master architect Rabirius.[113] The most important building Domitian restored was the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, which was said to have been covered with a gilded roof. Among those he completed were the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Arch of Titus, and the Colosseum, to which he added a fourth level and finished the interior seating area.[105]

Entertainment

Both Titus and Domitian were fond of gladiatorial games, and realised its importance to appease the citizens of Rome. In the newly constructed Colosseum, the Flavians provided for spectacular entertainments. The Inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre lasted for a hundred days and were said to be extremely elaborate, including gladiatorial combat, fights between wild animals (elephants and cranes), mock naval battles for which the theatre was flooded, horse races and chariot races.[110] During the games, wooden balls were dropped into the audience, inscribed with various prizes (clothing, gold, or even slaves), which could then be traded for the designated item.[110]

An estimated 135 million sestertii was spent on donativa, or congiaria, throughout Domitian's reign.[114] He also revived the practice of public banquets, which had been reduced to a simple distribution of food under Nero, while he invested large sums on entertainment and games. In 86, he founded the Capitoline Games, a quadrennial contest comprising athletic displays, chariot races, and competitions for oratory, music and acting.[115] Domitian himself supported the travels of competitors from the whole empire and attributed the prizes. Innovations were also introduced into the regular gladiatorial games, such as naval contests, night-time battles, and female and dwarf gladiator fights.[116] Finally, he added two new factions, Gold and Purple, to chariot races, besides the regular White, Red, Green and Blue teams.

Legacy

The Flavians, although a relatively short-lived dynasty, helped restore stability to an empire on its knees. Although all three have been criticised, especially based on their more centralised style of rule, they issued reforms that created a stable enough empire to last well into the 3rd century. However, their background as a military dynasty led to further marginalisation of the Senate, and a conclusive move away from princeps, or first citizen, and toward imperator, or emperor.

Little factual information survives about Vespasian's government during the ten years he was emperor; his reign is best known for financial reforms following the demise of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Vespasian was noted for his mildness and for loyalty to the people. For example, much money was spent on public works and the restoration and beautification of Rome: a new forum, the Temple of Peace, the public baths and the Colosseum.

Titus's record among ancient historians stands as one of the most exemplary of any emperor. All the surviving accounts from this period, many of them written by his own contemporaries such as Suetonius Tranquillus, Cassius Dio, and Pliny the Elder, present a highly favourable view towards Titus. His character has especially prospered in comparison with that of his brother Domitian. In contrast to the ideal portrayal of Titus in Roman histories, in Jewish memory "Titus the Wicked" is remembered as an evil oppressor and destroyer of the Temple. For example, one legend in the Babylonian Talmud describes Titus as having had sex with a whore on a Torah scroll inside the Temple during its destruction.[117]

Although contemporary historians vilified Domitian after his death, his administration provided the foundation for the peaceful empire of the 2nd century, and the culmination of the Pax Romana. His successors Nerva and Trajan were less restrictive, but, in reality, their policies differed little from Domitian's. Much more than a gloomy coda to the 1st century, the Roman Empire prospered between 81 and 96, in a reign which Theodor Mommsen described as the sombre but intelligent despotism of Domitian.[118]

Flavian family tree

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dynastic timeline

See also

Notes

- Jones (1992), p. 3

- Jones (1992), p. 1

- Jones (1992), p. 2

- Townend (1961), p. 62

- Smith, William, Sir, ed. 1813–1893 (1867). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Boston: Little, Brown and co. p. 1248.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jones (1992), p. 8

- Suetonius, Life of Domitian 1

- Suetonius, Life of Domitian 4

- Jones (1992), p. 7

- Jones (1992), pp. 9–11

- Jones & Milns (2002), pp. 95–96

- Jones (1992), p. 168

- Townend (1961), p. 57

- Jones (1992), p. 11

- Jones (1992), p. 38

- Suetonius. "44". Life of Titus.; with Jones and Milns, pp. 95–96

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews II.19.9

- Jones (1992), p. 13

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews III.1.2

- Josephus, The War of the Jews III.4.2

- Sullivan (1953), p. 69

- Wellesley (2000), p. 44

- Wellesley (2000), p. 45

- Sullivan (1953), p. 68

- Wellesley (2000), p. 126

- Waters (1964), p. 54

- Tacitus, Histories III.34

- Wellesley (2000), p. 166

- Wellesley (2000), p. 189

- Jones (1992), p. 14

- Wellesley (1956), p. 213

- Sullivan (1953), pp. 67–70

- Sullivan, Phillip (1953). "A Note on Flavian Accession". The Classical Journal: 67–70.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Vespasian 25

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Vespasian 9

- Suetonius, Life of Vespasian 23.4

- "Otho, Vitellius, and the Propaganda of Vespasian", The Classical Journal (1965), pp. 267–269

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 1

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.22–24

- Jones, Brian W. The Emperor Titus. New York: St. Martin's P, 1984. 143.

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Domitian 5

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Domitian 2

- Jones (1992), pp. 73–75

- Jones (1992), pp. 127–144

- Jones (1992), pp. 79–88

- Jones (1992), p. 131

- Jones (1992), pp. 138–142

- Jones (1992), pp. 196–198

- Waters, K. H. (1963). "The Second Dynasty of Rome". Phoenix. Classical Association of Canada. 17 (3): 198–218. doi:10.2307/1086720. JSTOR 1086720.

- Jones (1992), p. 164

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Vespasian 8

- Crook, John A. (1951). "Titus and Berenice". The American Journal of Philology. 72 (2): 162–175. doi:10.2307/292544. JSTOR 292544.

- Jones (1992), p. 18

- Jones (1992), p. 20

- Jones (1992), p. 22

- Jones (1992), p. 107

- Jones (1992), pp. 163–168

- Jones (1992), pp. 178–179

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, LXVI.2

- Jones (1992), p. 75

- Jone (1992), p. 73

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.6.1

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VI.9.3

- Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana 6.29 Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXV.6

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VII.5.5

- Josephus, The Wars of the Jews VII.5.6

- Tacitus, Agricola 24

- Jones (1992), p. 132

- Reed, Nicholas (1971). "The Fifth Year of Agricola's Campaigns". Britannia. 2: 143–148. doi:10.2307/525804. JSTOR 525804. S2CID 164089455.

- Tacitus, Agricola 29

- Jones (1992), p. 127

- Jones (1992), p. 131

- Jones (1992), p. 138

- Jones (1992), p. 141

- Jones (1992), p. 142

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVII.7

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVIII.14

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.22

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.23

- The exact number of casualties is unknown; however, estimates of the population of Pompeii range between 10,000 ("Pompeii Engineering". Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2009-03-10.) and 25,000 (), with at least a thousand bodies currently recovered in and around the city ruins.

- Suetonius, Life of Titus 8

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.24

- Crook (1963), p. 168

- Crook (1963), p. 169

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 9

- Jones (1992), p. 144

- Jones (1992), p. 145

- Jones (1992), p. 146

- Jones (1992), p. 149

- Tacitus, Agricola 45

- Suetonius, "Life of Domitian" 10

- For a full list of senatorial victims, see Jones (1992), pp. 182–188

- M. Arrecinus Clemens may have been exiled instead of executed, see Jones (1992), p. 187

- Charleswroth, M.P. (1938). "Flaviana". Journal of Roman Studies. 27: 54–62. doi:10.2307/297187. JSTOR 297187. S2CID 250344174.

- Jones, William "Some Thoughts on the Propaganda of Vespasian and Domitian", The Classical Journal, p. 251

- Aqueduct and roads dedication speak of previous emperors' neglect, CIL vi, 1257(ILS 218) and 931

- Josephus, Against Apion 9

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Vespasian 18

- Tacitus, Histories I.1; Josephus, The Life of Flavius Josephus 72; Pliny the Elder, Natural History, preface.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.12

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.13

- Jones (1992), p. 87

- Jones (1992), p. 93

- Jones (1992), p. 99

- Suetonius (1997). "Life of Vespasian 9". The Lives of Twelve Caesars. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-475-X. OCLC 40184695.

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-06-430158-3. OCLC 185448116.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (First ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 276–282. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History LXVI.25

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Titus 7

- Jones (1992), p. 79

- Jones (1992), pp. 84–88

- Jones (1992), p. 74

- Jones (1992), p. 103

- Jones (1992), p. 105

- Babylonian Talmud (Gittin 56b)

- Syme (1930), p. 67

References

- Grainger, John D. (2003). Nerva and the Roman Succession Crisis of 96 CE–99. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28917-3.

- Jones, Brian W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10195-6.

- Jones, Brian W.; Milns, Robert (2002). Suetonius: The Flavian Emperors: A Historical Commentary. London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-85399-613-0.

- Murison, Charles Leslie (2003). "M. Cocceius Nerva and the Flavians" (subscription required). Transactions of the American Philological Association. University of Western Ontario. 133 (1): 147–157. doi:10.1353/apa.2003.0008. S2CID 162211747.

- Sullivan, Philip B. (1953). "A Note on the Flavian Accession". The Classical Journal. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Inc. 49 (2): 67–70. JSTOR 3293160.

- Syme, Ronald (1930). "The Imperial Finances under Domitian, Nerva and Trajan". The Journal of Roman Studies. 20: 55–70. doi:10.2307/297385. JSTOR 297385. S2CID 163980436.

- Townend, Gavin (1961). "Some Flavian Connections". The Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 51 (1 & 2): 54–62. doi:10.2307/298836. JSTOR 298836. S2CID 163868319.

- Waters, K. H. (1964). "The Character of Domitian". Phoenix. Classical Association of Canada. 18 (1): 49–77. doi:10.2307/1086912. JSTOR 1086912.

- Wellesley, Kenneth (1956). "Three Historical Puzzles in Histories 3". The Classical Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. 6 (3/4): 207–214. doi:10.1017/S0009838800020188. JSTOR 636914. S2CID 170747190.

- Wellesley, Kenneth (2000) [1975]. The Year of the Four Emperors. Roman Imperial Biographies. London: Routledge. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-415-23620-1.

Further reading

External links

Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- Josephus, The War of the Jews, English translation

- Suetonius, On the Life of the Caesars

- Life of Vespasian, Latin text with English translation

- Life of Titus, Latin text with English translation

- Life of Domitian, Latin text with English translation

- Tacitus

Secondary material

- Donahue, John (2004-09-23). "Titus Flavius Vespasianus (A.D. 69–79)". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Donahue, John (2004-10-23). "Titus Flavius Vespasianus (A.D. 79–81)". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Donahue, John (1997-10-10). "Titus Flavius Domitianus (A.D. 81–96)". De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and their Families. Retrieved 2007-02-10.

- "A Gallery of Flavian Coins".