Crane (bird)

Cranes are a type of large bird with long legs and necks in the Gruidae family of the group Gruiformes. The family has 15 species placed in four genera which are Antigone, Balearica, Leucogeranus, and Grus.[1] They are large birds with long necks and legs, a tapering form, and long secondary feathers on the wing that project over the tail. Most species have muted gray or white plumages, marked with black, and red bare patches on the face, but the crowned cranes of the genus Balearica have vibrantly-coloured wings and golden "crowns" of feathers. Cranes fly with their necks extended outwards instead of bent into an S-shape and their long legs outstretched.

| Crane | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Superfamily: | Gruoidea |

| Family: | Gruidae Vigors, 1825 |

| Type genus | |

| Grus | |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

Cranes live on most continents, with the exception of Antarctica and South America. Some species and populations of cranes migrate over long distances; others do not migrate at all.[2] Cranes are solitary during the breeding season, occurring in pairs, but during the nonbreeding season, most species are gregarious, forming large flocks where their numbers are sufficient.

They are opportunistic feeders that change their diets according to the season and their own nutrient requirements. They eat a range of items from small rodents, eggs of birds, fish, amphibians, and insects to grain and berries. Cranes construct platform nests in shallow water, and typically lay two eggs at a time. Both parents help to rear the young, which remain with them until the next breeding season.[3] Most species of cranes have been affected by human activities and are at the least classified as threatened, if not critically endangered.[4] The plight of the whooping cranes of North America inspired some of the first US legislation to protect endangered species.

Description

Cranes are very large birds, often considered the world's tallest flying birds. They range in size from the demoiselle crane, which measures 90 cm (35 in) in length, to the sarus crane, which can be up to 176 cm (69 in), although the heaviest is the red-crowned crane, which can weigh 12 kg (26 lb) prior to migrating. They are long-legged and long-necked birds with streamlined bodies and large, rounded wings. The males and females do not vary in external appearance, but males tend to be slightly larger than females.[5]

The plumage of cranes varies by habitat. Species inhabiting vast, open wetlands tend to have more white in their plumage than do species that inhabit smaller wetlands or forested habitats, which tend to be more grey. These white species are also generally larger. The smaller size and colour of the forest species is thought to help them maintain a less conspicuous profile while nesting; two of these species (the common and sandhill cranes) also daub their feathers with mud which some observers suspect helps them to hide while nesting.

Most species of cranes and change the intensity of colour. Feathers on the head can be moved and erected in the blue, wattled, and demoiselle cranes for signaling, as well.

Also important to communication is the position and length of the trachea. In the two crowned cranes, the trachea is shorter and only slightly impressed upon the bone of the sternum, whereas the trachea of the other species is longer and penetrates the sternum. In some species, the entire sternum is fused to the bony plates of the trachea, and this helps amplify the crane's calls, allowing them to carry for several kilometres.[5][6]

Taxonomy and systematics

The family name Gruidae comes from the genus Grus, this genus name is obtained from the epithet of the common crane which is Ardea grus, it is named by Carl Linnaeus from the Latin word grus meaning "crane".[7]

The 15 living species of cranes are placed in four genera.[1] A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2010 found that the genus Grus, as then defined, was polyphyletic.[8] In the resulting rearrangement to create monophyletic genera, the Siberian crane was moved to the resurrected monotypic genus Leucogeranus, while the sandhill crane, the white-naped crane, the sarus crane, and the brolga were moved to the resurrected genus Antigone.[1] Some authorities recognize the additional genera Anthropoides (for the demoiselle crane and blue crane) and Bugeranus (for the wattled crane) on morphological grounds.

Evolution

The fossil record of cranes is incomplete. Apparently, the subfamilies were well distinct by the Late Eocene (around 35 mya). The present genera are apparently some 20 mya old. Biogeography of known fossil and the living taxa of cranes suggests that the group is probably of (Laurasian?) Old World origin. The extant diversity at the genus level is centered on (eastern) Africa, although no fossil record exists from there. On the other hand, it is peculiar that numerous fossils of Ciconiiformes are documented from there; these birds presumably shared much of their habitat with cranes back then already. Cranes are sister taxa to Eogruidae, a lineage of flightless birds; as predicted by the fossil record of true cranes, eogruids were native to the Old World. A species of true crane, Antigone cubensis, has similarly become flightless and ratite-like.

Fossil genera are tentatively assigned to the present-day subfamilies:

Gruinae

- Palaeogrus (Middle Eocene of Germany and Italy – Middle Miocene of France)

- Pliogrus (Early Pliocene of Eppelsheim, Germany)

- Camusia (Late Miocene of Menorca, Mediterranean)

- "Grus" conferta (Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Contra Costa County, US)[9]

Sometimes considered Balearicinae

- Geranopsis (Hordwell Late Eocene – Early Oligocene of England)

- Anserpica (Late Oligocene of France)

Sometimes considered Gruidae incertae sedis

- Eobalearica (Ferghana Late? Eocene of Ferghana, Uzbekistan)

- Probalearica (Late Oligocene? – Middle Pliocene of Florida, US, France?, Moldavia and Mongolia) – A nomen dubium?

- Aramornis (Sheep Creek Middle Miocene of Snake Creek Quarries, US)

Distribution and habitat

The cranes have a cosmopolitan distribution, occurring across most of the world continents. They are absent from Antarctica and, mysteriously, South America. East Asia has the highest crane diversity, with eight species, followed by Africa, which is home to five resident species and wintering populations of a sixth. Australia, Europe, and North America have two regularly occurring species each. Of the four crane genera, Balearica (two species) is restricted to Africa, and Leucogeranus (one species) is restricted to Asia; the other two genera, Grus (including Anthropoides and Bugeranus) and Antigone, are both widespread.[5][1]

Many species of cranes are dependent on wetlands and grasslands, and most species nest in shallow wetlands. Some species nest in wetlands, but move their chicks up onto grasslands or uplands to feed (while returning to wetlands at night), whereas others remain in wetlands for the entirety of the breeding season. Even the demoiselle crane and blue crane, which may nest and feed in grasslands (or even arid grasslands or deserts), require wetlands for roosting at night. The Sarus Crane in south Asia is unique in having a significant breeding population using agricultural fields to breed in areas alongside very high density of humans and intensive farming, largely due to the positive attitudes of farmers towards the cranes.[2] In Australia, the Brolga occurs in the breeding areas of Sarus Cranes in Queensland state, and they achieve sympatry by using different habitats. Sarus Cranes in Queensland largely live in Eucalyptus-dominated riverine, while most Brolgas use non-wooded regional ecosystems that include vast grassland habitats.[10] The only two species that do not always roost in wetlands are the two African crowned cranes (Balearica), which are the only cranes to roost in trees.[5]

Some crane species are sedentary, remaining in the same area throughout the year, while others are highly migratory, traveling thousands of kilometres each year from their breeding sites. A few species like Sarus Cranes have both migratory and sedentary populations, and healthy sedentary populations have a large proportion of cranes that are not territorial, breeding pairs.[11]

Behaviour and ecology

The cranes are diurnal birds that vary in their sociality by season and location. During the breeding season, they are territorial and usually remain on their territory all the time. In contrast in the non-breeding season, they tend to be gregarious, forming large flocks to roost, socialize, and in some species feed. Sarus Crane breeding pairs maintain territories throughout the year in south Asia, and non-breeding birds live in flocks that can also be seen throughout the year.[2][11] Large aggregations of cranes likely increase safety for individual cranes when resting and flying and also increase chances for young unmated birds to meet partners.[5]

Calls and communication

Cranes are highly vocal and have several specialized calls. The vocabulary begins soon after hatching with low, purring calls for maintaining contact with their parents, as well as food-begging calls. Other calls used as chicks include alarm calls and "flight intention" calls, both of which are maintained into adulthood. Cranes are noticed the most due to their loud duet calls that can be used to distinguish individual pairs.[12] Sarus crane trios produce synchronized unison calls called "triets" whose structure is identical to duets of normal pairs, but have a lower frequency.[13]

Feeding

_pair_at_Tsokar%252CLadakh.jpg.webp)

The cranes consume a wide range of food, both animal and plant matter. When feeding on land, they consume seeds, leaves, nuts and acorns, berries, fruit, insects, worms, snails, small reptiles, mammals, and birds. In wetlands and agriculture fields, roots, rhizomes, tubers, and other parts of emergent plants, other molluscs, small fish, eggs of birds and amphibians are also consumed, as well. The exact composition of the diet varies by location, season, and availability. Within the wide range of items consumed, some patterns are suggested but require specific investigation to confirm; the shorter-billed species usually feed in drier uplands, while the longer-billed species feed in wetlands.[5]

Cranes employ different foraging techniques for different food types and in different habitats. Tubers and rhizomes are dug for and a crane digging for them remains in place for some time digging and then expanding a hole to prise them out of the soil. In contrast both to this and the stationary wait and watch hunting methods employed by many herons, they forage for insects and animal prey by slowly moving forwards with their heads lowered and probing with their bills.[5]

Where more than one species of cranes exists in a locality, each species adopts separate niches to minimise competition. At one important lake in Jiangxi Province in China, the Siberian cranes feed on the mudflats and in shallow water, the white-naped cranes on the wetland borders, the hooded cranes on sedge meadows, and the last two species also feed on the agricultural fields along with the common cranes.[5] In Australia, where Sarus Cranes live alongside Brolgas, they have different diets: Sarus Cranes' diet consisted of diverse vegetation, while Brolga diet spanned a much wider range of trophic levels.[10] Some crane species such as the Common/ Eurasian crane use a kleptoparasitic strategy to recover from temporary reductions in feeding rate, particularly when the rate is below the threshold of intake necessary for survival.[14] Accumulated intake of during daytime shows a typical anti-sigmoid shape, with greatest increases of intake after dawn and before dusk.[15]

Breeding

_couple_parading_..._(32457893122).jpg.webp)

Cranes are perennially monogamous breeders, establishing long-term pair bonds that may last the lifetime of the birds. Pair bonds begin to form in the second or third years of life, but several years pass before the first successful breeding season. Initial breeding attempts often fail, and in many cases, newer pair bonds dissolve (divorce) after unsuccessful breeding attempts. Pairs that are repeatedly successful at breeding remain together for as long as they continue to do so.[5] In a study of sandhill cranes in Florida, seven of the 22 pairs studied remained together for an 11-year period. Of the pairs that separated, 53% was due to the death of one of the pair, 18% was due to divorce, and the fate of 29% of pairs was unknown.[16] Similar results had been found by acoustic monitoring (sonography/frequency analysis of duet and guard calls) in three breeding areas of common cranes in Germany over 10 years.[17]

Cranes are territorial and generally seasonal breeders. Seasonality varies both between and within species, depending on local conditions. Migratory species begin breeding upon reaching their summer breeding grounds, between April and June. The breeding season of tropical species is usually timed to coincide with the wet or monsoon seasons.[2] Artificial sources of water such as irrigation canals and irregular rainfall can sometimes provide adequate moisture to maintain wetland habitat outside the normal wet season, and allows for occasional aseasonal nesting throughout the year in few tropical species.[18]

Territory sizes also vary depending on location. Tropical species can maintain very small territories, for example sarus cranes in India can breed on territories as small as one hectare where the area is of sufficient quality and disturbance by humans is minimal. Even in areas with a high density of humans, in the absence of directed persecution, species like Sarus Crane maintain territories as small as 5 ha when agricultural crops and landscape conditions are suitable.[2] In contrast, red-crowned crane territories may require 500 hectares, and pairs may defend even larger territories than that, up to several thousand hectares. Territory defence is either acoustic with both birds performing the unison call, or more rarely, physical with attacks usually by the male.[5] Because of this, females are much less likely to retain the territory than males in the event of the death of a partner.[16] Rarely, breeding territorial crane pairs allow a third crane into the territory to form polygynous or polyandrous trios that improves the chances of survival of the pair's chicks.[13] Trios of Sarus cranes were seen largely in marginal habitats and third birds were young suggesting that third cranes would benefit by gaining experience.[13]

In mythology and symbolism

.jpg.webp)

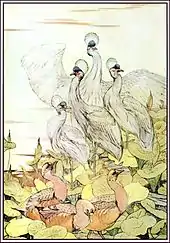

The cranes' beauty and spectacular mating dances have made them highly symbolic birds in many cultures with records dating back to ancient times. Crane mythology can be found in cultures around the world, from India to the Aegean, Arabia, China, Korea, Japan, Australia, and North America.

The Sanskrit epic poet Valmiki was inspired to write the first śloka couplet by the pathos of seeing a male sarus crane shot while dancing with its mate.[19][20]

In Mecca, in pre-Islamic Arabia, Allāt, Uzza, and Manāt were believed to be the three chief goddesses of Mecca, they were called the "three exalted cranes" (gharaniq, an obscure word on which 'crane' is the usual gloss). See The Satanic Verses for the best-known story regarding these three goddesses.

The Greek for crane is Γερανος (geranos), which gives us the cranesbill, or hardy geranium. The crane was a bird of omen. In the tale of Ibycus and the cranes, a thief attacked Ibycus (a poet of the sixth century BCE) and left him for dead. Ibycus called to a flock of passing cranes, which followed the attacker to a theater and hovered over him until, stricken with guilt, he confessed to the crime.

Pliny the Elder wrote that cranes would appoint one of their number to stand guard while they slept. The sentry would hold a stone in its claw, so that if it fell asleep, it would drop the stone and waken. A crane holding a stone in its claw is a well-known symbol in heraldry, and is known as a crane in its vigilance. Notably, however, the crest of Clan Cranstoun depicts a sleeping crane still in vigilance and holding the rock in its raised claw.[21]

Aristotle describes the migration of cranes in the History of Animals,[22] adding an account of their fights with Pygmies as they wintered near the source of the Nile. He describes as untruthful an account that the crane carries a touchstone inside it that can be used to test for gold when vomited up. (This second story is not altogether implausible, as cranes might ingest appropriate gizzard stones in one locality and regurgitate them in a region where such stone is otherwise scarce.)

Greek and Roman myths often portrayed the dance of cranes as a love of joy and a celebration of life, and the crane was often associated with both Apollo and Hephaestus.

In pre-modern Ottoman Empire, sultans would sometimes present a piece of crane feather (Turkish: turna teli) to soldiers of any group in the army (janissaries, sipahis, etc.) who performed heroically during a battle. Soldiers would attach this feather to their caps or headgear which would give them some sort of a rank among their peers.[23]

Throughout Asia, the crane is a symbol of happiness and eternal youth. In China, several styles of kung fu take inspiration from the movements of cranes in the wild, the most famous of these styles being Wing Chun, Hung Gar (tiger crane), and the Shaolin Five Animals style of fighting. Crane movements are well known for their fluidity and grace.

In Japan, the crane is one of the mystical or holy creatures (others include the dragon and the tortoise) and symbolizes good fortune and longevity because of its fabled life span of a thousand years. The crane is one of the subjects in the tradition of origami, or paper folding. An ancient Japanese legend promises that anyone who folds a thousand origami cranes will be granted a wish by a crane. In northern Hokkaidō, the women of the Ainu people performed a crane dance that was captured in 1908 in a photograph by Arnold Genthe. After World War II, the crane came to symbolize peace and the innocent victims of war through the story of schoolgirl Sadako Sasaki and her thousand origami cranes. Suffering from leukemia as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and knowing she was dying, she undertook to make a thousand origami cranes before her death at the age of 12. After her death, she became internationally recognised as a symbol of the innocent victims of war and remains a heroine to many Japanese girls.

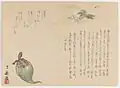

.jpg.webp) Crane, 18th century, by Mitsusuke (1675–1710), National Museum in Kraków

Crane, 18th century, by Mitsusuke (1675–1710), National Museum in Kraków Pine, Plum and Cranes, 1759, by Shen Quan (1682—1760), hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, the Palace Museum, Beijing

Pine, Plum and Cranes, 1759, by Shen Quan (1682—1760), hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, the Palace Museum, Beijing.jpg.webp)

Dwarves fighting cranes in northern Sweden, a 16th-century drawing by Olaus Magnus

Dwarves fighting cranes in northern Sweden, a 16th-century drawing by Olaus Magnus Cranes folded in origami paper

Cranes folded in origami paper Songha (Korean), Cranes and Pines, 19th century. Brooklyn Museum

Songha (Korean), Cranes and Pines, 19th century. Brooklyn Museum Tortoise Has New Year's Dream of Crane and Pine, around 1850, Brooklyn Museum

Tortoise Has New Year's Dream of Crane and Pine, around 1850, Brooklyn Museum Brass Crane Perched on a Tortoise, c. 1800–1894, from the Oxford College Archive of Emory University

Brass Crane Perched on a Tortoise, c. 1800–1894, from the Oxford College Archive of Emory University

See also

References

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2023). "Flufftails, finfoots, rails, trumpeters, cranes, limpkin". World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- Sundar, K.S. Gopi (2009). "Are Rice Paddies Suboptimal Breeding Habitat for Sarus Cranes in Uttar Pradesh, India?". The Condor. 111 (4): 611–623. doi:10.1525/cond.2009.080032. S2CID 198153258.

- Archibald, George W. (1991). Forshaw, Joseph (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Animals: Birds. London: Merehurst Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 1-85391-186-0.

- "Species at Risk - Conserving Endangered Cranes". Project Passenger Pigeon. Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum (The Chicago Academy of Sciences). Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- Archibald, George; Meine, Curt (1996). "Family Gruidae (Cranes)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 3, Hoatzin to Auks. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 60–81. ISBN 84-87334-20-2.

- Gaunt, Abbot; Sandra L. L. Gaunt; Henry D. Prange; Jeremy S. Wasser (1987). "The effects of tracheal coiling on the vocalizations of cranes (Aves; Gruidae)". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 161 (1): 43–58. doi:10.1007/BF00609454. S2CID 38224245.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, UK: Christopher Helm. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-4081-3326-2. OCLC 659731768.

- Krajewski, C.; Sipiorski, J.T.; Anderson, F.E. (2010). "Mitochondrial genome sequences and the phylogeny of cranes (Gruiformes: Gruidae)". Auk. 127 (2): 440–452. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.09045. S2CID 85412892.

- Miller, Alden H.; Sibley, Charles G. (1942). "A New Species of Crane from the Pliocene of California" (PDF). Condor. 44 (3): 126–127. doi:10.2307/1364260. JSTOR 1364260.

- Sundar, K.S. Gopi; Grant, John D.A.; Veltheim, Inka; Kittur, Swati; Brandis, Kate; McCarthy, Michael A.; Scambler, Elinor (2018). "Sympatric cranes in northern Australia: abundance, breeding success, habitat preference and diet". The Emu. 119 (1): 79–89. doi:10.1080/01584197.2018.1537673. S2CID 133977233.

- Sundar, K.S. Gopi (2006). "Effectiveness of road transects and wetland visits for surveying Black-necked Storks Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus and Sarus Cranes Grus antigone in India" (PDF). Forktail. 22: 179–181.

- "craneworld.de". craneworld.de. Archived from the original on 2012-07-20. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- Roy, Suhridam; Kittur, Swati; Sundar, K S Gopi (2022). "Sarus Crane Antigone antigone trios and their triets: Discovery of a novel social unit in cranes". Ecology. 103 (6): e3707. doi:10.1002/ecy.3707. PMID 35357696. S2CID 247840832.

- Bautista, L.M.; Alonso, J.C.; Alonso, J.A. (1998). "Foraging site displacement in common crane flocks" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 56 (5): 1237–1243. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0882. hdl:10261/46357. PMID 9819341. S2CID 23926741.

- Bautista, L.M.; Alonso, J.C. (2013). "Factors influencing daily food intake patterns in birds: a case study with wintering common cranes" (PDF). Condor. 115: 330–339. doi:10.1525/cond.2013.120080. hdl:10261/77900. S2CID 86505359.

- Nesbitt, Stephen A. (1989). "The Significance of Mate Loss in Florida Sandhill Cranes" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 101 (4): 648–651.

- Wessling, B. (2003). "Acoustic individual monitoring over several years (mainly Common Crane and Whooping Crane)". Craneworld.de. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- Sundar, K.S. Gopi; Yaseen, Mohammed; Kathju, Kandarp (2018). "The Role of Artificial Habitats and Rainfall Patterns in the Unseasonal Nesting of Sarus Cranes (Antigone antigone) in South Asia". Waterbirds. 41 (1): 80–86. doi:10.1675/063.041.0111. S2CID 89705278.

- Leslie, J. (1998). "A bird bereaved: The identity and significance of Valmiki's kraunca". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 26 (5): 455–487. doi:10.1023/A:1004335910775. S2CID 169152694.

- Hammer, Niels (2009). "Why Sārus Cranes epitomize Karuṇarasa in the Rāmāyaṇa". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. (Third Series). 19 (2): 187–211. doi:10.1017/S1356186308009334. S2CID 145356486.

- Arthur Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, T.C. and E.C. Jack, London, 1909, 247, https://archive.org/details/completeguidetoh00foxduoft.

- "The Internet Classics Archive | The History of Animals by Aristotle". Classics.mit.edu. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- Rami Mehmed Paşa, Münşeat, p. 141b. Flügel Catalogue, H.O. 179, Austrian National Library.

External links

- Saving Cranes website (ICF)

- Craneworld website, mainly in German

- individual recognition of cranes using frequency analysis of their calls

- Gruidae videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Crane sounds overview on xeno-canto.org

- Cranes of the World, by Paul Johnsgard

Myths and lore

- Crane Dance at the Tongdosa Temple (archive link, was dead)

- Thousand Cranes lore