Constitution of Austria

The Constitution of Austria (German: Österreichische Bundesverfassung) is the body of all constitutional law of the Republic of Austria on the federal level. It is split up over many different acts. Its centerpiece is the Federal Constitutional Law (Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz) (B-VG), which includes the most important federal constitutional provisions.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of Austria |

|---|

|

Apart from the B-VG, there are many other constitutional acts (called Bundesverfassungsgesetze, singular Bundesverfassungsgesetz, abbrev. BVG, i.e. without the hyphen) and individual provisions in statutes and treaties which are designated as constitutional (Verfassungsbestimmung). For example, the B-VG does not include a bill of rights, but provisions on civil liberties are split up over various constitutional pieces of legislation.

Over time, both the B-VG and the numerous pieces of constitutional law supplementing it have undergone hundreds of minor and major amendments and revisions.

History

Austria has been governed by multiple constitutions, including the Pillersdorf Constitution in 1848, the "irrevocable" Stadion Constitution from 1848 to 1851, the October Diploma in 1860, the February Patent from 1861 until 1865.

The B-VG was based on drafts whose principal author was Hans Kelsen and was first enacted on October 1, 1920. Since political agreement over a bill of rights could not be reached, the Basic Law on the General Rights of Citizens (Staatsgrundgesetz über die allgemeinen Rechte der Staatsbürger) of 1867 was left in place and designated as constitutional law.

Originally, the B-VG was very parliamentarian in character. The prerogative to enact law was to lie with a comparatively strong parliament, the Federal Assembly composed of two houses, the National Council and the Federal Council. The responsibility for implementing law was to reside with a cabinet headed by a chancellor, who was nominated by the National Council on a motion by its principal committee. A relatively weak president, who was elected by both houses, was to serve as head of state.

In 1929, the constitution underwent a revision significantly broadening the prerogatives of the president. In particular, the president was to be elected directly by the people rather than by the legislature. The president was also to be vested with the authority to dissolve the parliament, a power typically not held by presidents of parliamentary republics. He also had the authority to formally appoint the chancellor and the cabinet. On paper, the president was vested with powers comparable to those of the President of the United States. However, in practice his role remained mostly ceremonial and representative. For example, his right to appoint the chancellor was constrained by the National Council's power to censure the cabinet or individual ministers, meaning the president was all but required to ensure his choice of chancellor had the confidence of the National Council. He exercised many of his other executive functions on the advice of the chancellor. This move away from a government steered predominantly by a fairly large and (by definition) fractioned deliberative body towards a system concentrating power in the hands of a single autonomous leader was made in an attempt to appease the para-fascist movements (such as the Heimwehr, or later the Ostmärkische Sturmscharen and the Social Democratic Republikanischer Schutzbund) thriving in Austria at that time.

In 1934, following years of increasingly violent political strife and gradual erosion of the rule of law, the ruling Christian Social Party, which by then had turned to full-scale Austrofascism, formally replaced the constitution by a new basic law defining Austria as an authoritarian corporate state. The Austrofascist constitution was in force until Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938, ceasing to exist as a sovereign state. The Constitution of Austria was eventually reinstated on May 1, 1945, Austria having reestablished itself as an independent republic shortly before Nazi Germany's definitive collapse. The modifications enacted in 1929 were not then rescinded, and essentially remain in effect until this day, although the constitution has been heavily modified and amended since then.[1]

Structure

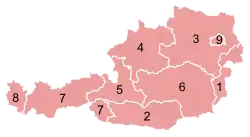

In area, the Republic of Austria is slightly smaller than Maine, Scotland, or Hokkaidō and home to a relatively ethnically and culturally homogeneous population of 8.8 million people. Given that more than one fifth of its inhabitants are concentrated in the city of Vienna and its suburbs, the nation is also naturally unipolar in terms of both economic and cultural activity. Austria's constitutional framework nevertheless characterizes the republic as a federation consisting of nine autonomous federal states:[2]

| English name | German name |  States of Austria | |

| 1. | Burgenland | Burgenland | |

| 2. | Carinthia | Kärnten | |

| 3. | Lower Austria | Niederösterreich | |

| 4. | Upper Austria | Oberösterreich | |

| 5. | Salzburg | Salzburg | |

| 6. | Styria | Steiermark | |

| 7. | Tyrol | Tirol | |

| 8. | Vorarlberg | Vorarlberg | |

| 9. | Vienna | Wien |

Like the federation, each of the nine states of Austria has a constitution defining it to be a republican entity governed according to the principles of representative democracy. The state constitutions congruently define the states to be unicameral parliamentary democracies; each state has a legislature elected by popular vote and a cabinet appointed by its legislature. The federal constitution defines Austria itself as a bicameral parliamentary democracy with near-complete separation of powers. Austria's government structure is thus very similar to that of much larger federal republics such as Germany or the United States. The main practical difference between Austria on one hand and Germany or the United States on the other is that Austria's states have comparatively little autonomy: almost all matters of practical importance, including but not limited to defense, foreign politics, criminal law, corporate law, most other aspects of economic law, education, academia, welfare, telecommunications, and the health care system, lie with the federation. The judiciary (including three supreme courts) is almost exclusively federal, with the exception of nine state administrative courts.[3]

Federal legislature

Federal legislative powers are vested in a body the constitution refers to as a parliament. Ever since the somewhat paradoxical 1929 revision of the constitution, which strengthened the formal separation of powers in Austria at the instigation of sympathizers of fascism, Austria's legislature technically bears more resemblance to a congress than to a parliament. As a practical matter, however, it continues to function as a parliament anyway. Austria's parliament consists of two houses, the National Council and the Federal Council. The 183 members of the National Council are elected by nationwide popular vote under statutes aiming at party-list proportional representation. The currently 64 members of the Federal Council are elected by Austria's nine state legislatures under a statute allocating seats roughly proportional to state population size (the largest Bundesland being entitled to twelve members and the others accordingly, but no state to less than three). In theory, the National Council and the Federal Council are peers. As a practical matter, the National Council is decidedly more powerful; the predominance of the National Council is such that Austrians frequently use the term "parliament" to refer to just the National Council instead of to the parliament as a whole.

While bicameral legislatures such as the Congress of the United States allow bills to originate in both chambers, Austrian federal legislation always originates in the National Council, never in the Federal Council. In theory, bills can be sponsored by National Council members, by the federal cabinet, by popular initiative, or through a motion supported by at least one-third of the members of the Federal Council. In practice, most bills are proposed by the cabinet and passed after merely token debate. Bills passed by the National Council are sent to the Federal Council for affirmation. If the Federal Council approves of the bill or simply does nothing for a period of eight weeks, the bill has succeeded. Bills passed by both houses (or passed by the National Council and ignored by the Federal Council) are ultimately signed into law by the federal president. The president does not have the power to veto bills; a signature is a technical formality notarizing that the bill has been introduced and resolved upon in accordance to the procedure stipulated by the constitution. Legislation may be vetoed only on the ground that its genesis, not its substance, is in violation of basic law. Adjudicating upon the constitutionality of the bill itself is the exclusive prerogative of the Constitutional Court.[4]

Provided that the bill in question neither amends the constitution such that states' rights are curtailed nor in some other way pertains to the organization of the legislature itself, the National Council can force the bill into law even if the Federal Council rejects it; a National Council resolution overruling a Federal Council objection merely has to meet a higher quorum than a regular resolution. For this reason, the Federal Council has hardly any real power to prevent the adoption of legislation, the National Council being able to override it easily. The Federal Council is sometimes compared to the British House of Lords, another deliberative body able to stall but usually not to strike down a proposed law. While the House of Lords occasionally exercises its stalling power, however, the Federal Council hardly ever does. Since the parties controlling the National Council consistently also hold a majority in the Federal Council, the latter gives its blessing to essentially everything the former has adopted.

Federal executive

Federal executive authority is shared by the federal president and federal cabinet. The president is elected by popular vote for a term of six years and limited to two consecutive terms of office. The president is the head of state and appoints the cabinet, a body consisting of the federal chancellor and a number of ministers. The president also appoints the members of the Constitutional Court and numerous other public officials, represents the republic in international relations, accredits foreign ambassadors, and acts as the nominal commander in chief of Austria's armed forces.

While Austria's federal cabinet is technically not answerable to the legislature (except for a motion of censure), it would be almost totally paralyzed without the active support of the National Council. Since constitutional convention prevents the president from using his power to dissolve the National Council on his own authority, the president is unable to hector the legislature into doing his or her bidding, and the cabinet is for all intents and purposes subject to National Council approval. The cabinet's composition therefore reflects National Council election results rather than presidential election outcomes.

After elections, it is customary for the president to ask the leader of the strongest party to become chancellor and form a cabinet. The list is then submitted to the president by the chancellor-to-be; the president usually adopts it without much argument, although there has been at least one case in recent history where the president did refuse to install a minister. The president retains the right to dismiss the whole cabinet at will, or certain ministers of it at the request of the chancellor. Although elected for a five-year term, the National Council can dissolve itself at any time, bringing about new elections.

The federal chancellor's dual role as executive officeholder and heavyweight party official well connected to the legislature makes the chancellor far more powerful than the formally senior federal president. Actual executive authority thus lies with the chancellor and his or her ministers, while the federal president is a figurehead rather than an actual head of government. Austria's presidents are largely content with their ceremonial role, striving for the role of impartial mediator and dignified elder statesman, and more or less consistently steer clear of the murky waters of hands-on politics. In recent times, however, former president Heinz Fischer was known to comment occasionally on current political issues.

Judicial and administrative review

Federal and state judicial authority, in particular responsibility for judicial review of administrative acts, lies with the Administrative and Constitutional Court System, a structure essentially consisting of the Constitutional Court and the Administrative Court. The Constitutional Court examines the constitutionality of laws passed by Parliament, the legality of regulations by Federal ministers and other administrative authorities and finally alleged infringements of constitutional rights of individuals through decisions of the lower administrative courts. It also tries disputes between the federation and its member states, demarcation disputes between other courts and impeachments of the federal president (serving as State Court in that matter.)

The Administrative Court tries all kinds of cases which involve ex officio decisions by public officials or bodies and which are not dealt with by the Constitutional Court. Note that only the Constitutional Court has the authority to strike down laws.

In recent years, an increasing number of tribunals of a judicial nature (article 133 point 4 B-VG) hade been introduced in a number of areas to improve the review of the conduct of administrative authorities. The most important among them were the Länder independent administrative chambers (Unabhängige Verwaltungssenate - UVS), who decided, amongst other things, on second authority in proceedings relating to administrative contraventions as well as recourses against acts of direct exercise of command and constraint power from administrative authorities. Other such chambers were competent in the area of tax law (Unabhängiger Finanzsenat - UFS), in terms of asylum (Unabhängiger Bundesasylsenat - UBAS), in relation to environmental matters (Unabhängiger Umweltsenat) or in the field of telecommunications (Unabhängiger Bundeskommunikationssenat). Although all these tribunals were formally part of the administrative organization, their members had guarantees of independence and irremovability and their powers may thus be compared to jurisdictions. Their rulings could be challenged before the Administrative or the Constitutional Court. In 2014 these administrative tribunals were abolished in favour of eleven administrative courts—one in each state (Landesverwaltungsgerichte) and two on the federal level (Bundesverwaltungsgericht, Bundesfinanzgericht).

The Austrian constitution was the second in the world (nearly contemporaneous with Czechoslovakia) to enact judicial review by a Constitutional Court. It had been established in 1919 and gained the right to revise the laws of the federal states that year. After the new constitution had been adopted in 1920, the court was also entitled to revise national laws according to the constitution. This scheme of a separate constitutional court able to review legislative acts for their constitutionality came to be known as the "Austrian system". After the U.S. and the British Dominions (such as Canada and Australia), where the regular court system is in charge of judicial review, Austria was one of the earliest countries to have judicial review at all (although the Czechoslovak Constitution came into force earlier, the establishment of the Court's new rights itself predated the Czechoslovak Court by a couple of months[5]). Many European countries adopted the Austrian system of review after World War II.

Judiciary

Judicial powers not committed to the Administrative and Constitutional Court System are vested with the Civil and Criminal Court System, a structure consisting of civil courts on the one hand and criminal courts on the other hand. Civil courts try all cases in which both the claimant and the respondent are private citizens or corporations, including but not limited to contract and torts disputes: Austria's legal system, having evolved from that of the Roman Empire, implements civil law and therefore lacks the distinction between courts of law and courts of equity sometimes found in common law jurisdictions. Civil courts do not try suits against the federation or its states in their capacity as administrative units, but only when acting in the form of private law.

Most cases are tried before District Courts (Bezirksgerichte, abbrev.: BG, singular: Bezirksgericht), with Regional Courts (Landesgerichte, abbrev.: LG, singular: Landesgericht) serving as courts of appeal and the Supreme Court (Oberster Gerichtshof, abbrev.: OGH) serving as the court of last resort. In cases considered particularly grave or technically involved, the Regional Courts serve as courts of first instance and specialized Regional Courts of Appeal (Oberlandesgerichte, abbrev.: OLG, singular: Oberlandesgericht) serve as courts of appeal, the Supreme Court still being the court of last resort.

Unlike with court systems such as that of the United States federal judiciary, parties have a statutory right to appeal. Although access to the Supreme Court has been successively restricted to matters of some importance in recent years, higher courts can generally not simply refuse to review a decision reached by subordinate courts.

Note that the Supreme Court (Oberster Gerichtshof - OGH), the Constitutional Court (Verfassungsgerichtshof - VfGH) and the Administrative Court (Verwaltungsgerichtshof - VwGH) are three separate high courts, none being senior to the other two.

Civil and human rights

Most closely resembling a bill of rights in Austria is the Basic Law on the General Rights of Nationals of the Kingdoms and Länder represented in the Council of the Realm, a decree issued by Emperor Franz Josef on December 21, 1867 in response to pressure by liberal insurgents.

A very important part of Austria's canon of constitutional civil liberties thus originated as an imperatorial edict predating the current Constitution of Austria by roughly fifty years, the reason being that the framers of the Constitution in 1920 could not agree on a set of civil liberties to include in the constitution proper: as a lowest common denominator, they resorted to this Basic Law of 1867. Since then, other civil liberties have been set out in other constitutional laws, and Austria is party to the European Convention of Human Rights, which, too, has been implemented as a directly applicable constitutional law in Austria.

Given the fact that the Constitutional Court has begun to interpret the B-VG's equal treatment clause and other constitutional rights rather broadly since at least the early 1980s, civil rights are, as a general matter, relatively well protected.

Further checks and balances

In addition to their legislative capacity, the members of the two houses of parliament have the authority to impeach the president, who is then tried before the Constitutional Court, serving as State Court, or call for a referendum to have the federal president removed from office. Exertion of these emergency powers is a two-step process: first the National Council requests the president to be impeached or subjected to referendum, then the members of the National Council and the Federal Council convene in joint session, thus forming the National Assembly, and decide on the National Council's motion. If a referendum is held, and the President is not removed from office by popular vote, he is automatically considered re-elected for another six-year term (although he may still not serve for more than twelve consecutive years). The National Council will then be dissolved automatically and new general elections must be held.

The president may also dissolve the National Council, but only once for the same reason during his term of office. Note that the president does not have the power to veto specific acts of legislation: no matter how vehemently he objects to some particular bill, or believes it to be unconstitutional, all he can actually do is threaten to dismiss the government or dissolve the National Council before the bill is actually passed.

None of these emergency powers have been exercised thus far.

Criticism and reform proposals

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of Austrian constitutional law is the relative ease with which it can be changed, combined with the fact that a constitutional amendment need not be incorporated into the main text of the B-VG, or for that matter any of the more important parts of the constitutional body, but can be enacted as a separate constitutional act, or even as a simple section within any act, simply designated as "constitutional" (Verfassungsbestimmung).

In reality, all that is needed is a majority of two-thirds in the National Council. Only in the case of a fundamental change ("Gesamtänderung") of the constitution a confirmation by referendum is required. Austria's accession to EU in 1995 was considered such a change.

Over the years, the Austrian legal system became littered with thousands of constitutional provisions, split up over numerous acts. The reason for this was in many cases that the legislature—in particular when the governing coalition possessed a two-thirds majority in the National Council (such as between 1945–1966, 1986–1994, 1995–1999, and 2007–2008)—enacted laws that were considered "constitutionally problematic" as constitutional laws, effectively protecting them from judicial review by the Constitutional Court. There have even been cases where a provision that had been previously declared unconstitutional by the competent Constitutional Court has subsequently been enacted as constitutional law. Needless to say, the Constitutional Court did and does not like that practice, and has declared that it might, in a not-too-distant future, consider such changes, in their entirety, as "fundamental change" to the Constitution, which would require a public referendum.

From 2003 to 2005, a constitutional convention (Österreich Konvent)[6] consisting of representatives of all parties, representatives of all layers of government and many groups of Austrian society debated whether and how to reform the constitution. There was no general consensus on a draft for a new constitution, however, and some minor points that were universally agreed upon have yet to be implemented.

See also

Former constitutions

- Pillersdorf Constitution (1848)

- Kremsier Constitution (1848)

- March Constitution (1849)

- October Diploma (1860)

- February Patent (1861)

- December Constitution (1867)

- May Constitution (1934)

References

- For a detailed history of Austrian constitutional law from 1848 to 1955, see: Lehner, Oskar (2007). Österreichische Verfassungs- und Verwaltungsgeschichte. Mit Grundzügen der Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte (in German) (4 ed.). Linz: Trauner. ISBN 978-3-85487-339-6.

- B-VG, article 2, section (2).

- "Republic of Austria: Parliament". Parliament of Austria. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Austria 1920 (reinst. 1945, rev. 2013)". Constitute. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Langášek, Tomáš (2011). Ústavní soud Československé republiky a jeho osudy v letech 1920-1948. Vydavatelství a nakladatelství Aleš Čeněk, s. r. o. ISBN 978-80-7380-347-6.

- "The Austrian Convention and Constitutional Reform". Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz (B-VG). (English and German versions). from Rechtsinformationssystem, RIS. Retrieved on May 10, 2010.

- Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz (B-VG). (English and German versions). from Rechtsinformationssystem, RIS. Last updated on January 1, 2015. Retrieved on October 29, 2020.

External links

- Official Austrian Law online research tool (RechtsInformationsSystem, RIS) (English version), (German, full version), (Bilingual German-English version)

- Austrian Constitutional Court

- Constitutional Developments in Austria

- Verfassungen Österreichs

- Supreme Administrative Court