Auto Union racing cars

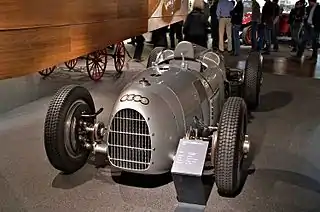

The Auto Union Grand Prix racing cars types A to D were developed and built by a specialist racing department of Auto Union's Horch works in Zwickau, Germany, between 1933 and 1939, after the company bought a design by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche in 1933. The Auto Union type B streamlined body was designed by Paul Jaray.[1]

Of the 4 Auto Union racing cars, the Types A, B and C, used from 1934 to 1937 had supercharged V16 engines, and the final car, the Type D used in 1938 and 1939 (built to new 1938 regulations), had a supercharged 3L V12 that developed almost 550 horsepower. All of the designs were difficult to handle due to extreme power/weight ratios (wheelspin could be induced at over 100 mph (160 km/h)), and marked oversteer due to uneven weight distribution (all models were tail heavy). The Type D was easier to drive because of its smaller, lower mass engine that was better positioned toward the vehicle's center of mass.

Between 1935 and 1937, Auto Unions won 25 races, driven by Ernst von Delius, Tazio Nuvolari, Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Stuck and Achille Varzi. Auto Union proved particularly successful in the 1936 and 1937 seasons. Their main competition came from the Mercedes Benz team, which also raced sleek, silver cars. Known as the Silver Arrows, the cars of the two German teams dominated Grand Prix racing until the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

Background

P-Wagen project

Having been made redundant from Steyr Automobile, Dr. Ferdinand Porsche founded Porsche in Stuttgart, with engineering colleagues including Karl Rabe, and financial backing from Adolf Rosenberger. Unfortunately, car commissions were low in the depressed economic climate, so Porsche founded the subsidiary company Hochleistungsfahrzeugbau GmbH (HFB) (High Performance Car Ltd.) in 1932 to develop a racing car, for which he had no customer.[2]

In 1933, Grand Prix racing was dominated by French and Italian marques Bugatti, Alfa Romeo and Maserati. In early 1933, governing body AIACR announced a new formula, with the main regulation that the weight of the car without driver, fuel, oil, water and tyre was not allowed to exceed 750 kg (1,650 lb). This was created to restrict the size of engine that could be used, with the authority estimating that this weight limit would allow around 2.5-litre engines.[3]

Based on Max Wagner's mid-engined 1923 Benz Tropfenwagen, or "Teardrop" aerodynamic design, also built in part by Rumpler engineers,[4] the experimental P-Wagen project racing car (P stood for Porsche) was designed according to the regulations of the 750 kg formula. On 15 November chief engineer Rabe submitted the first draft to the planning office of a racing car for the new formula, with Josef Kales responsible for the V16 engine, while Rabe also held responsibility for the chassis.[2]

Auto Union

In 1932 Auto Union Gmbh was formed, comprising struggling auto manufacturers Audi, DKW, Horch and Wanderer. The chairman of the board of Directors, Baron Klaus von Oertzen wanted a show piece project, so at fellow director Adolf Rosenberger's insistence, von Oertzen met with Porsche, who had done work for him before.[2]

At the 1933 Berlin Motor Show, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler announced two new programs:[2]

- The people's car: a project that would eventually become the KdF-wagen

- A state-sponsored motor racing programme: to develop a "high speed German automotive industry," the foundation of which would be an annual sum of 500,000 Reichsmarks to Mercedes-Benz

German racing driver Hans Stuck had met Hitler before he became Chancellor, and not being able to gain a seat at Mercedes, accepted the invitation of Rosenberger to join him, von Oertzen, and Porsche in approaching the Chancellor. In a meeting in the Reich Chancellery, Hitler agreed with Porsche that for the glory of Germany, it would be better for two companies to develop the project, resulting in Hitler agreeing to pay £40,000 for the country's best racing car of 1934, as well as an annual stipend of 250,000 Reichsmarks[2] (£20,000)[5] each for Mercedes and Auto Union. (In time, this would climb to £250,000.)[6] This highly annoyed Mercedes, who had already developed their Mercedes-Benz W25, which nevertheless was gratified, its racing program having financial difficulties since 1931.[6] It resulted in a heated exchange both on and off the racing track between the two companies until World War Two.

Having garnered state funds, Auto Union bought Hochleistungs Motor GmbH and hence the P-Wagen Project for 75,000 Reichsmarks, relocating the company to Chemnitz.[2]

Design

The rear mid-engine, rear-wheel-drive layout was unusual at the time. From front to rear the layout comprised radiator, driver, fuel tank, and engine. The layout would return to Grand Prix racing in the late 1950s by British manufacturer Cooper Car Company.

The problem with early mid-engined design was the stiffness of the contemporary ladder chassis and suspension. The car's turning angle changed as the momentum of the centrally mounted engine increased on the chassis, causing oversteer. All Auto Unions had independent suspension, with parallel trailing arms and torsion bars at the front. At the rear, Porsche tried to counter the tendency to oversteer by using a then-advanced swing axle suspension on the early cars. On the later Type D, rear suspension was a de Dion system, following the lead of Mercedes-Benz, but the supercharged engines eventually produced almost 550 horsepower, which exacerbated the oversteer.

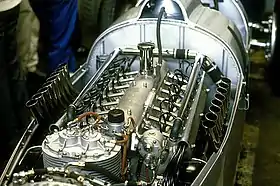

The original Porsche-designed V16 was modified as a V12 when in 1938 the Grand Prix regulations set a limit of 3 litres on supercharged engines. Originally designed as a 6-litre, the first Auto Union engines displaced 4,360 cc and developed 295 PS (217 kW). They had two cylinder blocks, inclined at an angle of 45 degrees, with a single overhead camshaft to operate all 32 valves. The intake valves in the hemispherical cylinder heads were connected to the camshaft by rocker arms, while for the exhaust valves the rocker arms were connected to the camshaft by pushrods that passed through tubes situated above the spark plugs; thus the engine had three valve covers. The engine provided optimum torque at low engine speeds, and Bernd Rosemeyer later drove an Auto Union around the Nürburgring in a single gear to prove the engine's flexibility.

The body underwent wind-tunnel testing at the German Institute for Aerodynamics, a scientific organization that still exists. With the fuel tank located in the centre of the car directly behind the driver, the front-rear weight distribution remained unchanged as the fuel was used; the same location is used in modern open-wheel racing cars for the same reason. The chassis tubes originally piped coolant from the radiator to the engine, but this was eventually abandoned owing to leaks.

Racing

Development

The development of Auto Union racing cars began 1933 by specialists of Horch works. The first cars ran in the winter 1933/34, on the Nürburgring, AVUS and Monza. Further development was stopped completely in 1942.

Unlike Mercedes, who had former racing driver turned designer Rudolf Uhlenhaut, who could provide excellent feedback on the car and required developments; Auto Union were forced to create in-car measuring systems to provide additional feedback. Auto Union used a clockwork mechanism and a paper disc to record data such as engine revs while the car was being tested, allowing the engineers to study the collected data at a later date.[3] It was found that additional work was needed on the car's cornering behaviour, as accelerating out of a corner would cause the inside rear wheel to spin furiously. This was much abated by the use of a Porsche innovation, limited slip differential, manufactured by ZF, which was introduced at the end of the 1935 season.

Co-operation between Porsche and Auto Union continued through the Types A, B and C, until the 750 kg (1,650 lb) formula ended in 1937, as engineering developments had resulted in engines producing great horsepower in lightweight vehicles, and hence high speeds and excessive accidents. Dr. Ing. Robert Eberan von Eberhorst was responsible for the new Type D car, which while still retaining the 750 kg (1,650 lb) minimum weight, also restricted capacity to 3 litres with a supercharger, or 4.5 litres without. The Type D employed a 12-cylinder engine, while the hillclimb versions, where the capacity limit was not enforced, used a different gearbox and final drive to retain the 16-cylinder engine of the Type C.

Racing results

This section includes only results of second or better.

The list of drivers for the initial 1934 season was headed by Hans Stuck; he won the German, Swiss and Czechoslovakian Grand Prix races (as well as finishing second in the Italian Grand Prix and Eifelrennen), along with wins in a number of hill-climb races, becoming European Mountain Champion. (There was no European Championship for the circuit races that year). August Momberger placed second in the Swiss Grand Prix.

In 1935, the engine had been enlarged to five litres displacement, producing 370 bhp (280 kW). Achille Varzi joined the team and won the Tunis Grand Prix in Carthage and the Coppa Acerbo in Pescara (along with placing second in the Tripoli Grand Prix). Stuck won the Italian Grand Prix (along with second at the German Grand Prix), plus his usual collection of hill-climb wins, again taking the European Mountain Championship. The new sensation, Bernd Rosemeyer, won the Czech Grand Prix (and managed a second at the Eifelrennen and Coppa Acerbo).

Hans Stuck also managed to break speed records, reaching 199 mph (320 km/h) on an Italian autostrada in a streamlined car with enclosed cockpit.[7] Lessons learned from this streamlining were later applied to the T80 land speed record car.

For 1936, the engine had grown to the full 6 litres, and was now producing 620 bhp (460 kW); and reaching 258 mph (415 km/h) in the hands of Rosemeyer and his teammates, the Auto Union Type C dominated the racing world. Rosemeyer won the Eifelrennen, German, Swiss and Italian Grands Prix and the Coppa Acerbo (as well as second in the Hungarian Grand Prix). He was crowned European Champion (Auto Union's only win of the driver's championship), and for good measure also took the European Mountain Championship. Varzi won the Tripoli Grand Prix (and took second at the Monaco, Milan and Swiss Grands Prix). Stuck placed second in the Tripoli and German Grands Prix, and Ernst von Delius took second in the Coppa Acerbo.

In 1937, the car was basically unchanged and did surprisingly well against the new Mercedes-Benz W125, winning 5 races to the 7 of Mercedes-Benz. Rosemeyer took the Eifelrennen and Donington Grand Prix, the Coppa Acerbo, and the Vanderbilt Cup (and well as second in the Tripoli Grand Prix). Rudolf Hasse won the Belgian Grand Prix (Stuck placed second). Von Delius managed second in the Avus Grand Prix.

In addition to the new 3-litre formula, 1938 brought other challenges, principally the death of Rosemeyer early in the year, in an attempt on the land speed record. The famed Tazio Nuvolari joined the team, and won the Italian and Donington Grands Prix, in what was otherwise a thin year for the team, other than yet another European Mountain Championship for Stuck.

.jpg.webp)

In 1939, as war clouds gathered over Europe, Nuvolari won the Yugoslavia Grand Prix in Belgrade (with a second place in the Eifel). Hermann P. Müller won the 1939 French Grand Prix (and took second in the German Grand Prix). Hasse managed a second place in the 1939 Belgian Grand Prix, and Georg Meier a second in the French.

Complete European Championship results

(key) (results in bold indicate pole position, results in italics indicate fastest lap)

Cars today

Very rarely were racing cars of the period kept, as components of early cars if required were scavenged for later models and repairs. Secondly, what did remain was often scrapped to provide funds for additional development.

During the latter part of World War II, an estimated eighteen Auto Union team cars were hidden in a colliery outside Zwickau, Saxony, where the Auto Union race shop was based. In 1945 the invading Russian Army discovered the cars, and they were retained as war possessions. As Zwickau post-war was located in Soviet controlled Communist East Germany, what little of the Auto Union racing cars existed were shipped back to the Soviet Union, distributed to scientific institutes and motor manufacturers including NAMI for research. The Auto Union company itself was forced to relocate to West Germany, where it was re-incorporated in Ingolstadt in 1949, ultimately evolving into Audi as it is known today.

Today, it is believed that most of the cars were probably reduced to scrap, and that no Type A or Type B cars exist today. Presently it is believed that only one Type C and three Type D cars, and a Type C/D hill climbing car remain.

The sole remaining Type C was originally left to a German museum by Auto Union, after the death of Bernd Rosemeyer resulted in only two or three of these historic cars running. Damaged by bombing during the war, its body today still shows these marks. In 1979/80, Audi commissioned restoration of the car, undertaking a preservation-level overhaul to the body, engine and transmission.

Another car was taken to Moscow to study its technology. In 1976, it was at the ZIL factory in Moscow and scheduled to be cut up for scrap metal when Viktors Kulbergs, president of the Antique Automobile Club of Latvia, brought it for the Riga Motor Museum.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Audi engineers authenticated the car as a 16-cylinder hill-climbing Auto Union that combined types C and D. Audi acquired it in exchange for a replica on a condition that all non-replaceable parts were kept at original car and replica was built on replaceable parts plus one of made parts that were originally on Audi made replica. Purchase/exchange was done for undisclosed sum of money, and in 1997 commissioned British engineering companies Crostwaite & Gardiner of Buxted and Roach Manufacturing of Ower to restore the original and create the replica. The original, which now resides in the Audi Motor Museum, appears at car shows and is also demonstrated at race meetings by long-time Audi racing driver Hans Stuck Jr., son of the original driver Hans Stuck. The replica, which was unveiled at the 2007 Festival of Speed at Goodwood House, England, with Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason as driver,[9] is exhibited in Riga.[10]

American car enthusiast Paul Karassik tracked down chassis No.19 in Russia, adding an original engine from a separate D-type carcass and handing it over in 1990 to Crosthwaite and Gardiner to restore to its original form. In February 2007, it was due to be auctioned by Christie's in Paris.[11] Although expected to be the most expensive car ever sold at auction at more than $12 million, the car did not find a buyer in the sealed auction. This was because of a discrepancy that was found with the chassis and engine numbers and the fact that they did not correspond with the numbers expected to be found on the car that it was believed to be.[12] The car went on auction in August 2009, with Bonhams estimating a sale price of around £5.5million.[13] During Bonhams 2009 Monterey auction, the bidding stalled at $6 million, and the vehicle was not sold.[14]

Replicas

For 2000, Audi commissioned a Type C Streamline, which in May 2000 raced around the banked curve of the famous Montlhéry circuit. This was 63 years after its premier at AVUS in May 1937, when Bernd Rosemeyer took a car of this type to a speed of 380 km/h (236 mph) on the straights.[10] Now resident in the Audi Mobile museum in Ingolstadt, the car has appeared at various autoshows around the world, including the 2009 Goodwood Festival of Speed commemorating Audi's 100th birthday.[10]

In 2004, Audi announced the rebuilt of Auto Union Wanderer Streamline Specials. The three cars were built by European car restorer Werner Zinke GmbH. As part of the celebration, Audi Tradition commissioned a limited edition 1:43 scale model of the car, bearing the start number 17.[15] The rebuilt cars also entered the Liège–Rome–Liège long-distance run 65 years after their original Liège-Rome-Liège runs.[16] Two of the cars, owned by Audi Tradition, went on display in its Museum in Ingolstadt, while the third car is owned by Belgian Audi importer D'Ieteren.[17]

Auto Union clones

In 1947, Automobiltechnisches Büro (ATB) created the Sokol Typ 650 Formula Two racer in the German Democratic Republic, using the talents of chassis designer Otto Seidan and engine designer Walther Träger (both former Auto Union employees), along with spare Auto Union parts and resembled the Type D. As Awtowelo it was successfully tested but never raced.

Type C pedal car

In 2007, Audi announced the sale of 999 1:2 scale Auto Union Type C pedal cars. The car was designed at Munich design studio. It features hydraulic dual-disc brake and its speed is controlled by the 7-speed hub gear with back-pedalling brake function. The car was made from aluminium space frame and the aluminium body panels. The seats, framing and steering wheel have been upholstered in leather by a bag-maker, as in the Audi TT, while the spoke wheels were custom-made. The steering wheel can be removed to make getting in and out easier, as in the original. The prototype of the pedal car was unveiled at the Paris Motor Show in autumn 2006.[18]

Auto Union Type C e-tron study (2011)

It is a version of 1:2 scale Auto Union Type C made of aluminum and carbon-look material, based on the Type C pedal car. It included rear wheel drive electric motor rated 1.5 PS (1 kW; 1 hp) and 40 N⋅m (29.50 lb⋅ft) (maximum 60 N⋅m (44.25 lb⋅ft)), a lithium-ion battery, a reverse gear. The vehicle has range of around 25 km (15.53 mi), with top speed of 30 km/h (18.64 mph). The battery can be charged at a standard 230 volt household socket.

The vehicle was unveiled in 62nd International Toy Fair in Nuremberg.[19]

Technical details

| Auto Union Racing Cars | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| characteristic | Type A (1934) | Type B (1935) | Type C (1936–37) | Type D (1938–39) | |

image |  | .jpg.webp) | .jpg.webp) |  | |

| engine orientation | longitudinal | longitudinal | longitudinal | longitudinal | |

| engine configuration | V16 | V16 | V16 | V12 | |

| cylinder bank angle | 45° | 45° | 45° | 60° | |

| engine displacement | 4,358 cubic centimetres (265.9 cu in) | 4,954 cubic centimetres (302.3 cu in) | 6,008 cubic centimetres (366.6 cu in) | 2,986 cubic centimetres (182.2 cu in) | |

| bore x stroke | 68 mm (2.68 in) x 75 mm (2.95 in) | 72.5 mm (2.85 in) x 75 mm (2.95 in) | 75 mm (2.95 in) x 85 mm (3.35 in) | 65 mm (2.56 in) x 75 mm (2.95 in) | |

| crankshaft | one-piece from Cr-Ni steel | one-piece from Cr-Ni steel | slidingstored (Hirth) | roll-stored | |

| valvetrain, ignition system | single camshaft | single camshaft | single camshaft, 2x ignition magnetos | triple camshaft | |

| aspiration | 1x Roots supercharger | 1x Roots supercharger | 1x Roots supercharger | 1 or 2x Roots supercharger | |

| compressor pressure | 0.61 bars (8.8 psi) | 0.75 bars (10.9 psi) | 0.95 bars (13.8 psi) (max) | 1.67 bars (24.2 psi) | |

| motive power | 295 PS (217 kW; 291 hp) @ 4,500 rpm | 375 PS (276 kW; 370 hp) @ 4,800 rpm | 485–520 PS (357–382 kW; 478–513 hp) @ 5,000 rpm | 420–460 PS (309–338 kW; 414–454 hp) @ 7,000 rpm | |

| torque | 530 N⋅m (391 lbf⋅ft) @ 2,700 rpm | 660 N⋅m (487 lbf⋅ft) @ 2,700 rpm | 882 N⋅m (651 lbf⋅ft) @ 2,500 rpm | 550 N⋅m (406 lbf⋅ft) @ 4,000 rpm | |

| transmission gears | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| maximum speed | 280 km/h (174 mph) | 340 km/h (211 mph) | 340 km/h (211 mph) | ||

| brakes | 400 mm (15.7 in), system Porsche hydraulic | 400 mm (15.7 in), system Porsche hydraulic | 400 mm (15.7 in), system Porsche hydraulic | 400 mm (15.7 in), system Porsche hydraulic | |

| shock absorber | friction absorber | friction absorber | friction absorber | front: hydraulic rear: hydraulic/friction | |

| front suspension | Crank semi-trailing arm (see Volkswagen Beetle) | Crank semi-trailing arm | |||

| rear suspension | Pendelachse with torsion bar suspension (in the back) | De-Dion-axle with torsion bar suspension | |||

| chassis | steel tube ladder framework, main pipe diameter: 75 mm (3.0 in) | steel tube ladder framework, main pipe diameter: 75 mm (3.0 in) | steel tube ladder framework, main pipe diameter: 105 mm (4.1 in) | steel tube ladder framework, main pipe diameter: 105 mm (4.1 in) | |

| wheelbase | 2,900 mm (114.2 in) | 2,800 mm (110.2 in) | |||

| axle track width | 1,420 mm (55.9 in) | 1,390 mm (54.7 in) | |||

| dimensions length × width × height | 3,920 mm (154.3 in) × 1,690 mm (66.5 in) × 1,020 mm (40.2 in) | 4,200 mm (165.4 in) × 1,660 mm (65.4 in) × 1,060 mm (41.7 in) | |||

| fuel capacity | 200 L (44.0 imp gal; 52.8 US gal) | ||||

| dry weight | 825 kg (1,819 lb) | 825 kg (1,819 lb) | 824 kg (1,817 lb) | 850 kg (1,874 lb) | |

| notes | Type D brought about by change of rules | ||||

References

Notes

- Scheppe, Wolfgang (2023). Paul Jaray - Die Vernunft der Stromlinie. Berlin: Kunsthaus Dahlem. pp. 14–15.

- "Auto Union Type C". DDavid.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- "Auto Union Racing Cars". BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- Wise, David Burgess. "Rumpler: One Aeroplane which Never Flew", in Northey, Tom, ed. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis, 1974), Vol. 17, p. 1964.

- Setright, L. J. K. "Mercedes-Benz: The German Fountain-head", in Northey, Tom, ed. World of Automobiles (London: Orbis, 1974), Vol. 11, p. 1311.

- Setright, p. 1312.

- G.E.T. Eyston; Barré Lyndon (1935). Motor Racing and Record Breaking.

- "THE GOLDEN ERA – OF GRAND PRIX RACING". kolumbus.fi. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Damon Lavrinc (24 June 2008). "Audi to debut Auto Union "Silver Arrow" Type D reconstruction at Goodwood". Autoblog.com. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Auto Union Type C". seriouswheels.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- Van onze verslaggever Theo Stielstra. "Miljoenen voor 'Hitlers Porsche' – Economie – de Volkskrant" (in Dutch). Volkskrant.nl. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "'World's most valuable car' fails to sell - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Bonhams Auctioneers. "1939 Auto Union 3-liter 'D-Type' V12 Grand Prix Racing Single-Seater Chassis no. '19' Engine no. 17". Bonhams.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- Frank Filipponio. "Monterey 2009: Auto Union is a no-sale at Bonhams". Autoblog.com. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Audi Rebuilds Historic Auto Union Wanderer Streamline Specials". Worldcarfans.com. 31 March 2004. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Sensational Comeback of the Wanderer Streamline Special". Worldcarfans.com. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Rare 'Streamline Special' Wanderers back on the road following Audi Tradition restoration". Classicdriver.com. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- Alex Nunez (3 August 2007). "Pedal to the Metal: Audi offering Auto Union Type C pedal car". Autoblog.com. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- Audi turns pedal car into another e-tron for German toy fair

Bibliography

- Alexandrow, Nicolaj (2004). Kirchberg, Peter (ed.). Dem Silber auf der Spur: Das Schicksal der Auto-Union-Rennwagen [On the Trail of Silver: The Fate of the Auto Union Racing Cars] (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 3613024020.

- Bamsey, Ian (1990). Auto Union V16 Supercharged: A Technical Appraisal. A Foulis motoring book. Sparkford, Somerset, England; Newbury Park, CA, USA: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 0854298045.

- Boschen, Lothar; Barth, Jürgen (1988). Das große Buch der Porsche-Sondertypen und -Konstruktionen: von 1931 bis heute – Technik zu Lande, zu Wasser und in der Luft [The Big Book of Porsche Special Types and Designs: from 1931 to today – technology on land, on water and in the air] (in German) (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 3879438056.

- Cancellieri, Gianni; DeAgostini, Cesare; Schröder, Martin (1980). Auto-Union: Die grossen Rennen 1934-39 [Auto-Union: The Great Races 1934-39] (in German) (expanded 1st German ed.). Hannover: Schröder und Weise. ISBN 3922787045.

- Clarke, R.M., ed. (1986). On Audi & Auto Union 1952-1980. Road & Track Series. Cobham, Surrey, UK: Brooklands Books. ISBN 0948207876.

- ——————, ed. (1986). On Audi & Auto Union 1980-1986. Road & Track Series. Cobham, Surrey, UK: Brooklands Books. ISBN 0948207884.

- Earl, Cameron C. (1996) [1947]. Quick Silver: An Investigation into the Development of German Grand Prix Racing Cars 1934-1939 (2nd, reprinted ed.). London: H.M.S.O. ISBN 0112905501.

- Edler, Karl-Heinz; Roediger, Wolfgang (1990) [1956]. Die deutschen Rennfahrzeuge: technische Entwicklung der letzten 20 Jahre [German Racing Cars: Technical development over the past 20 years] (in German) (2nd, reprinted ed.). Leipzig: Fachbuchverlag Leipzig. ISBN 3343004359.

- Eichhammer, Michael [in German] (2004). Silberpfeile und Kanonen: Die Geschichte der Auto Union Rennwagen und ihrer Fahrer [Silver Arrows and Cannons: The History of Auto Union Racing Cars and their Drivers] (in German). Bruckmühl, Germany: Wieland Verlag. ISBN 398087091X.

- Frankenberg, Richard von (1973) [1961]. Porsche: the Man and his Cars (revised ed.). Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire, UK: G.T. Foulis & Co. ISBN 0854290907.

- Kirchberg, Peter (1982). Grand-Prix-Report Auto-Union 1934 bis 1939 (in German). Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 3879438765.

- ———————, ed. (2008). Bernd Rosemeyer: Die Schicksalsfahrt [Bernd Rosemeyer: The Fateful Journey]. Edition Audi-Tradition (in German). Bielefeld, Germany: Delius Klasing. ISBN 9783768825054.

- Knittel, Stefan (1980). Auto Union Grand Prix Wagen: Ein faszinierendes Kapitel Renngeschichte der Dreissiger Jahre [Auto Union Grand Prix Cars: A Fascinating Chapter of Racing History in the Thirties] (in German). München: Verlag Schrader & Partner. p. 30 (units partly converted). ISBN 392261700X.

- Ludvigsen, Karl (2009). German Racing Silver: Drivers, Cars and Triumphs of German Motor Racing. Racing Colours Series. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 9780711033689.

- Merten, Holger (2 December 2002). "Auto Union - The history of the AU racing department Part 1: The small workshop that created motor racing history (1931-1935)". 8w.forix.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- Nixon, Chris (1998). Auto Union Album 1934 – 1939. London: Transport Bookman Publications. ISBN 0851840566.

- —————— (2003) [1986]. Racing the Silver Arrows: Mercedes-Benz versus Auto Union 1934-1939 (revised ed.). Isleworth, Middlesex, UK: Transport Bookman Publications. ISBN 0851840558.

- Posthumus, Cyril (1967). The 16-cylinder G.P. Auto Union. No. 59. Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications. OCLC 918155024.

- Pritchard, Anthony (2008). Silver Arrows In Camera: A photographic history of the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union Racing Teams 1934-39. Sparkford, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 9781844254675.

- Schrader, Halwart (1995). Silberpfeile: die Legendären Rennwagen, 1934 bis 1955 [Silver Arrows: The Legendary Racing Cars, 1934 to 1955] (in German). Königswinter, Germany: Heel Verlag. ISBN 3893654283.

- Sebastian, Ludwig (1952). Hinter dröhnenden Motoren: Bernd Rosemeyers Monteur erzählt [Behind the Roaring Engines: Bernd Rosemeyer's mechanic tells the story] (in German). Wien-Heidelberg: Verlag Carl Ueberreuter. OCLC 73669865.

- Vann, Peter (photographer) and authors (2001). Auto Union GP Race and Record Cars: Their Reconstruction and Restoration. St. Paul, MN, USA: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0760313075.

External links

- August Horch Museum Zwickau

- AUTO UNION Sales Brochures 1939

- AutoUnion: the cars, the drivers and the history

- Film of Auto Union winning the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup Race (VanderbiltCupRaces.com)

- The legendary "Silver Arrows"

- The small workshop that created motor racing history (1931–1935)

- What's left of the Auto Unions?

- THE GOLDEN ERA OF GRAND PRIX RACING – AUTO UNION Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine