Automation

Automation describes a wide range of technologies that reduce human intervention in processes, namely by predetermining decision criteria, subprocess relationships, and related actions, as well as embodying those predeterminations in machines.[1][2] Automation has been achieved by various means including mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic, electrical, electronic devices, and computers, usually in combination. Complicated systems, such as modern factories, airplanes, and ships typically use combinations of all of these techniques. The benefit of automation includes labor savings, reducing waste, savings in electricity costs, savings in material costs, and improvements to quality, accuracy, and precision.

| Part of a series on |

| Automation |

|---|

| Automation in general |

| Robotics and robots |

| Impact of automation |

| Trade shows and awards |

Automation includes the use of various equipment and control systems such as machinery, processes in factories, boilers,[3] and heat-treating ovens, switching on telephone networks, steering, and stabilization of ships, aircraft, and other applications and vehicles with reduced human intervention.[4] Examples range from a household thermostat controlling a boiler to a large industrial control system with tens of thousands of input measurements and output control signals. Automation has also found a home in the banking industry. It can range from simple on-off control to multi-variable high-level algorithms in terms of control complexity.

In the simplest type of an automatic control loop, a controller compares a measured value of a process with a desired set value and processes the resulting error signal to change some input to the process, in such a way that the process stays at its set point despite disturbances. This closed-loop control is an application of negative feedback to a system. The mathematical basis of control theory was begun in the 18th century and advanced rapidly in the 20th. The term automation, inspired by the earlier word automatic (coming from automaton), was not widely used before 1947, when Ford established an automation department.[5] It was during this time that the industry was rapidly adopting feedback controllers, which were introduced in the 1930s.[6]

The World Bank's World Development Report of 2019 shows evidence that the new industries and jobs in the technology sector outweigh the economic effects of workers being displaced by automation.[7] Job losses and downward mobility blamed on automation have been cited as one of many factors in the resurgence of nationalist, protectionist and populist politics in the US, UK and France, among other countries since the 2010s.[8][9][10][11][12]

History

Early history

It was a preoccupation of the Greeks and Arabs (in the period between about 300 BC and about 1200 AD) to keep accurate track of time. In Ptolemaic Egypt, about 270 BC, Ctesibius described a float regulator for a water clock, a device not unlike the ball and cock in a modern flush toilet. This was the earliest feedback-controlled mechanism.[13] The appearance of the mechanical clock in the 14th century made the water clock and its feedback control system obsolete.

The Persian Banū Mūsā brothers, in their Book of Ingenious Devices (850 AD), described a number of automatic controls.[14] Two-step level controls for fluids, a form of discontinuous variable structure controls, were developed by the Banu Musa brothers.[15] They also described a feedback controller.[16][17] The design of feedback control systems up through the Industrial Revolution was by trial-and-error, together with a great deal of engineering intuition. Thus, it was more of an art than a science. It was not until the mid-19th century that the stability of feedback control systems was analyzed using mathematics, the formal language of automatic control theory.

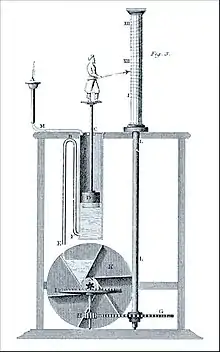

The centrifugal governor was invented by Christiaan Huygens in the seventeenth century, and used to adjust the gap between millstones.[18][19][20]

Industrial Revolution in Western Europe

The introduction of prime movers, or self-driven machines advanced grain mills, furnaces, boilers, and the steam engine created a new requirement for automatic control systems including temperature regulators (invented in 1624; see Cornelius Drebbel), pressure regulators (1681), float regulators (1700) and speed control devices. Another control mechanism was used to tent the sails of windmills. It was patented by Edmund Lee in 1745.[21] Also in 1745, Jacques de Vaucanson invented the first automated loom. Around 1800, Joseph Marie Jacquard created a punch-card system to program looms.[22]

In 1771 Richard Arkwright invented the first fully automated spinning mill driven by water power, known at the time as the water frame.[23] An automatic flour mill was developed by Oliver Evans in 1785, making it the first completely automated industrial process.[24][25]

A centrifugal governor was used by Mr. Bunce of England in 1784 as part of a model steam crane.[26][27] The centrifugal governor was adopted by James Watt for use on a steam engine in 1788 after Watt's partner Boulton saw one at a flour mill Boulton & Watt were building.[21] The governor could not actually hold a set speed; the engine would assume a new constant speed in response to load changes. The governor was able to handle smaller variations such as those caused by fluctuating heat load to the boiler. Also, there was a tendency for oscillation whenever there was a speed change. As a consequence, engines equipped with this governor were not suitable for operations requiring constant speed, such as cotton spinning.[21]

Several improvements to the governor, plus improvements to valve cut-off timing on the steam engine, made the engine suitable for most industrial uses before the end of the 19th century. Advances in the steam engine stayed well ahead of science, both thermodynamics and control theory.[21] The governor received relatively little scientific attention until James Clerk Maxwell published a paper that established the beginning of a theoretical basis for understanding control theory.

20th century

Relay logic was introduced with factory electrification, which underwent rapid adaption from 1900 through the 1920s. Central electric power stations were also undergoing rapid growth and the operation of new high-pressure boilers, steam turbines and electrical substations created a large demand for instruments and controls. Central control rooms became common in the 1920s, but as late as the early 1930s, most process controls were on-off. Operators typically monitored charts drawn by recorders that plotted data from instruments. To make corrections, operators manually opened or closed valves or turned switches on or off. Control rooms also used color-coded lights to send signals to workers in the plant to manually make certain changes.[28]

The development of the electronic amplifier during the 1920s, which was important for long-distance telephony, required a higher signal-to-noise ratio, which was solved by negative feedback noise cancellation. This and other telephony applications contributed to the control theory. In the 1940s and 1950s, German mathematician Irmgard Flügge-Lotz developed the theory of discontinuous automatic controls, which found military applications during the Second World War to fire control systems and aircraft navigation systems.[6]

Controllers, which were able to make calculated changes in response to deviations from a set point rather than on-off control, began being introduced in the 1930s. Controllers allowed manufacturing to continue showing productivity gains to offset the declining influence of factory electrification.[29]

Factory productivity was greatly increased by electrification in the 1920s. U.S. manufacturing productivity growth fell from 5.2%/yr 1919–29 to 2.76%/yr 1929–41. Alexander Field notes that spending on non-medical instruments increased significantly from 1929 to 1933 and remained strong thereafter.[29]

The First and Second World Wars saw major advancements in the field of mass communication and signal processing. Other key advances in automatic controls include differential equations, stability theory and system theory (1938), frequency domain analysis (1940), ship control (1950), and stochastic analysis (1941).

Starting in 1958, various systems based on solid-state[30][31] digital logic modules for hard-wired programmed logic controllers (the predecessors of programmable logic controllers [PLC]) emerged to replace electro-mechanical relay logic in industrial control systems for process control and automation, including early Telefunken/AEG Logistat, Siemens Simatic, Philips/Mullard/Valvo Norbit, BBC Sigmatronic, ACEC Logacec, Akkord Estacord, Krone Mibakron, Bistat, Datapac, Norlog, SSR, or Procontic systems.[30][32][33][34][35][36]

In 1959 Texaco's Port Arthur Refinery became the first chemical plant to use digital control.[37] Conversion of factories to digital control began to spread rapidly in the 1970s as the price of computer hardware fell.

Significant applications

The automatic telephone switchboard was introduced in 1892 along with dial telephones. By 1929, 31.9% of the Bell system was automatic.[38]: 158 Automatic telephone switching originally used vacuum tube amplifiers and electro-mechanical switches, which consumed a large amount of electricity. Call volume eventually grew so fast that it was feared the telephone system would consume all electricity production, prompting Bell Labs to begin research on the transistor.[39]

The logic performed by telephone switching relays was the inspiration for the digital computer. The first commercially successful glass bottle-blowing machine was an automatic model introduced in 1905.[40] The machine, operated by a two-man crew working 12-hour shifts, could produce 17,280 bottles in 24 hours, compared to 2,880 bottles made by a crew of six men and boys working in a shop for a day. The cost of making bottles by machine was 10 to 12 cents per gross compared to $1.80 per gross by the manual glassblowers and helpers.

Sectional electric drives were developed using control theory. Sectional electric drives are used on different sections of a machine where a precise differential must be maintained between the sections. In steel rolling, the metal elongates as it passes through pairs of rollers, which must run at successively faster speeds. In paper making paper, the sheet shrinks as it passes around steam-heated drying arranged in groups, which must run at successively slower speeds. The first application of a sectional electric drive was on a paper machine in 1919.[41] One of the most important developments in the steel industry during the 20th century was continuous wide strip rolling, developed by Armco in 1928.[42]

Before automation, many chemicals were made in batches. In 1930, with the widespread use of instruments and the emerging use of controllers, the founder of Dow Chemical Co. was advocating continuous production.[43]

Self-acting machine tools that displaced hand dexterity so they could be operated by boys and unskilled laborers were developed by James Nasmyth in the 1840s.[44] Machine tools were automated with Numerical control (NC) using punched paper tape in the 1950s. This soon evolved into computerized numerical control (CNC).

Today extensive automation is practiced in practically every type of manufacturing and assembly process. Some of the larger processes include electrical power generation, oil refining, chemicals, steel mills, plastics, cement plants, fertilizer plants, pulp and paper mills, automobile and truck assembly, aircraft production, glass manufacturing, natural gas separation plants, food and beverage processing, canning and bottling and manufacture of various kinds of parts. Robots are especially useful in hazardous applications like automobile spray painting. Robots are also used to assemble electronic circuit boards. Automotive welding is done with robots and automatic welders are used in applications like pipelines.

Space/computer age

With the advent of the space age in 1957, controls design, particularly in the United States, turned away from the frequency-domain techniques of classical control theory and backed into the differential equation techniques of the late 19th century, which were couched in the time domain. During the 1940s and 1950s, German mathematician Irmgard Flugge-Lotz developed the theory of discontinuous automatic control, which became widely used in hysteresis control systems such as navigation systems, fire-control systems, and electronics. Through Flugge-Lotz and others, the modern era saw time-domain design for nonlinear systems (1961), navigation (1960), optimal control and estimation theory (1962), nonlinear control theory (1969), digital control and filtering theory (1974), and the personal computer (1983).

Advantages, disadvantages, and limitations

Perhaps the most cited advantage of automation in industry is that it is associated with faster production and cheaper labor costs. Another benefit could be that it replaces hard, physical, or monotonous work.[45] Additionally, tasks that take place in hazardous environments or that are otherwise beyond human capabilities can be done by machines, as machines can operate even under extreme temperatures or in atmospheres that are radioactive or toxic. They can also be maintained with simple quality checks. However, at the time being, not all tasks can be automated, and some tasks are more expensive to automate than others. Initial costs of installing the machinery in factory settings are high, and failure to maintain a system could result in the loss of the product itself.

Moreover, some studies seem to indicate that industrial automation could impose ill effects beyond operational concerns, including worker displacement due to systemic loss of employment and compounded environmental damage; however, these findings are both convoluted and controversial in nature, and could potentially be circumvented.[46]

The main advantages of automation are:

- Increased throughput or productivity

- Improved quality

- Increased predictability

- Improved robustness (consistency), of processes or product

- Increased consistency of output

- Reduced direct human labor costs and expenses

- Reduced cycle time

- Increased accuracy

- Relieving humans of monotonously repetitive work [47]

- Required work in development, deployment, maintenance, and operation of automated processes — often structured as “jobs”

- Increased human freedom to do other things

Automation primarily describes machines replacing human action, but it is also loosely associated with mechanization, machines replacing human labor. Coupled with mechanization, extending human capabilities in terms of size, strength, speed, endurance, visual range & acuity, hearing frequency & precision, electromagnetic sensing & effecting, etc., advantages include:[48]

- Relieving humans of dangerous work stresses and occupational injuries (e.g., fewer strained backs from lifting heavy objects)

- Removing humans from dangerous environments (e.g. fire, space, volcanoes, nuclear facilities, underwater, etc.)

The main disadvantages of automation are:

- High initial cost

- Faster production without human intervention can mean faster unchecked production of defects where automated processes are defective.

- Scaled-up capacities can mean scaled-up problems when systems fail — releasing dangerous toxins, forces, energies, etc., at scaled-up rates.

- Human adaptiveness is often poorly understood by automation initiators. It is often difficult to anticipate every contingency and develop fully preplanned automated responses for every situation. The discoveries inherent in automating processes can require unanticipated iterations to resolve, causing unanticipated costs and delays.

- People anticipating employment income may be seriously disrupted by others deploying automation where no similar income is readily available.

Paradox of automation

The paradox of automation says that the more efficient the automated system, the more crucial the human contribution of the operators. Humans are less involved, but their involvement becomes more critical. Lisanne Bainbridge, a cognitive psychologist, identified these issues notably in her widely cited paper "Ironies of Automation."[49] If an automated system has an error, it will multiply that error until it is fixed or shut down. This is where human operators come in.[50] A fatal example of this was Air France Flight 447, where a failure of automation put the pilots into a manual situation they were not prepared for.[51]

Limitations

- Current technology is unable to automate all the desired tasks.

- Many operations using automation have large amounts of invested capital and produce high volumes of products, making malfunctions extremely costly and potentially hazardous. Therefore, some personnel is needed to ensure that the entire system functions properly and that safety and product quality are maintained.[52]

- As a process becomes increasingly automated, there is less and less labor to be saved or quality improvement to be gained. This is an example of both diminishing returns and the logistic function.

- As more and more processes become automated, there are fewer remaining non-automated processes. This is an example of the exhaustion of opportunities. New technological paradigms may, however, set new limits that surpass the previous limits.

Current limitations

Many roles for humans in industrial processes presently lie beyond the scope of automation. Human-level pattern recognition, language comprehension, and language production ability are well beyond the capabilities of modern mechanical and computer systems (but see Watson computer). Tasks requiring subjective assessment or synthesis of complex sensory data, such as scents and sounds, as well as high-level tasks such as strategic planning, currently require human expertise. In many cases, the use of humans is more cost-effective than mechanical approaches even where the automation of industrial tasks is possible. Therefore, algorithmic management as the digital rationalization of human labor instead of its substitution has emerged as an alternative technological strategy.[53] Overcoming these obstacles is a theorized path to post-scarcity economics.[54]

Societal impact and unemployment

Increased automation often causes workers to feel anxious about losing their jobs as technology renders their skills or experience unnecessary. Early in the Industrial Revolution, when inventions like the steam engine were making some job categories expendable, workers forcefully resisted these changes. Luddites, for instance, were English textile workers who protested the introduction of weaving machines by destroying them.[55] More recently, some residents of Chandler, Arizona, have slashed tires and pelted rocks at self-driving car, in protest over the cars' perceived threat to human safety and job prospects.[56]

The relative anxiety about automation reflected in opinion polls seems to correlate closely with the strength of organized labor in that region or nation. For example, while a study by the Pew Research Center indicated that 72% of Americans are worried about increasing automation in the workplace, 80% of Swedes see automation and artificial intelligence (AI) as a good thing, due to the country's still-powerful unions and a more robust national safety net.[57]

In the U.S., 47% of all current jobs have the potential to be fully automated by 2033, according to the research of experts Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne. Furthermore, wages and educational attainment appear to be strongly negatively correlated with an occupation's risk of being automated.[58] Even highly skilled professional jobs like a lawyer, doctor, engineer, journalist are at risk of automation.[59]

Prospects are particularly bleak for occupations that do not presently require a university degree, such as truck driving.[60] Even in high-tech corridors like Silicon Valley, concern is spreading about a future in which a sizable percentage of adults have little chance of sustaining gainful employment.[61] "In The Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee argue that "...there's never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there's never been a worse time to be a worker with only 'ordinary' skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate."[62] As the example of Sweden suggests, however, the transition to a more automated future need not inspire panic, if there is sufficient political will to promote the retraining of workers whose positions are being rendered obsolete.

According to a 2020 study in the Journal of Political Economy, automation has robust negative effects on employment and wages: "One more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment-to-population ratio by 0.2 percentage points and wages by 0.42%."[63]

Research by Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne of the Oxford Martin School argued that employees engaged in "tasks following well-defined procedures that can easily be performed by sophisticated algorithms" are at risk of displacement, and 47% of jobs in the US were at risk. The study, released as a working paper in 2013 and published in 2017, predicted that automation would put low-paid physical occupations most at risk, by surveying a group of colleagues on their opinions.[64] However, according to a study published in McKinsey Quarterly[65] in 2015 the impact of computerization in most cases is not the replacement of employees but the automation of portions of the tasks they perform.[66] The methodology of the McKinsey study has been heavily criticized for being intransparent and relying on subjective assessments.[67] The methodology of Frey and Osborne has been subjected to criticism, as lacking evidence, historical awareness, or credible methodology.[68][69] Additionally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that across the 21 OECD countries, 9% of jobs are automatable.[70]

The Obama administration pointed out that every 3 months "about 6 percent of jobs in the economy are destroyed by shrinking or closing businesses, while a slightly larger percentage of jobs are added."[71] A recent MIT economics study of automation in the U.S. from 1990 to 2007 found that there may be a negative impact on employment and wages when robots are introduced to an industry. When one robot is added per one thousand workers, the employment to population ratio decreases between 0.18 and 0.34 percentages and wages are reduced by 0.25–0.5 percentage points. During the time period studied, the US did not have many robots in the economy which restricts the impact of automation. However, automation is expected to triple (conservative estimate) or quadruple (a generous estimate) leading these numbers to become substantially higher.[72]

Based on a formula by Gilles Saint-Paul, an economist at Toulouse 1 University, the demand for unskilled human capital declines at a slower rate than the demand for skilled human capital increases.[73] In the long run and for society as a whole it has led to cheaper products, lower average work hours, and new industries forming (i.e., robotics industries, computer industries, design industries). These new industries provide many high salary skill-based jobs to the economy. By 2030, between 3 and 14 percent of the global workforce will be forced to switch job categories due to automation eliminating jobs in an entire sector. While the number of jobs lost to automation is often offset by jobs gained from technological advances, the same type of job loss is not the same one replaced and that leading to increasing unemployment in the lower-middle class. This occurs largely in the US and developed countries where technological advances contribute to higher demand for highly skilled labor but demand for middle-wage labor continues to fall. Economists call this trend "income polarization" where unskilled labor wages are driven down and skilled labor is driven up and it is predicted to continue in developed economies.[74]

Unemployment is becoming a problem in the U.S. due to the exponential growth rate of automation and technology. According to Kim, Kim, and Lee (2017:1), "[a] seminal study by Frey and Osborne in 2013 predicted that 47% of the 702 examined occupations in the U.S. faced a high risk of decreased employment rate within the next 10–25 years as a result of computerization." As many jobs are becoming obsolete, which is causing job displacement, one possible solution would be for the government to assist with a universal basic income (UBI) program. UBI would be a guaranteed, non-taxed income of around 1000 dollars per month, paid to all U.S. citizens over the age of 21. UBI would help those who are displaced take on jobs that pay less money and still afford to get by. It would also give those that are employed with jobs that are likely to be replaced by automation and technology extra money to spend on education and training on new demanding employment skills. UBI, however, should be seen as a short-term solution as it doesn't fully address the issue of income inequality which will be exacerbated by job displacement.

Lights-out manufacturing

Lights-out manufacturing is a production system with no human workers, to eliminate labor costs.

Lights out manufacturing grew in popularity in the U.S. when General Motors in 1982 implemented humans "hands-off" manufacturing to "replace risk-averse bureaucracy with automation and robots". However, the factory never reached full "lights out" status.[75]

The expansion of lights out manufacturing requires:[76]

- Reliability of equipment

- Long-term mechanic capabilities

- Planned preventive maintenance

- Commitment from the staff

Health and environment

The costs of automation to the environment are different depending on the technology, product or engine automated. There are automated engines that consume more energy resources from the Earth in comparison with previous engines and vice versa. Hazardous operations, such as oil refining, the manufacturing of industrial chemicals, and all forms of metal working, were always early contenders for automation.

The automation of vehicles could prove to have a substantial impact on the environment, although the nature of this impact could be beneficial or harmful depending on several factors. Because automated vehicles are much less likely to get into accidents compared to human-driven vehicles, some precautions built into current models (such as anti-lock brakes or laminated glass) would not be required for self-driving versions. Removing these safety features would also significantly reduce the weight of the vehicle, thus increasing fuel economy and reducing emissions per mile. Self-driving vehicles are also more precise concerning acceleration and breaking, and this could contribute to reduced emissions. Self-driving cars could also potentially utilize fuel-efficient features such as route mapping that can calculate and take the most efficient routes. Despite this potential to reduce emissions, some researchers theorize that an increase in the production of self-driving cars could lead to a boom in vehicle ownership and use. This boom could potentially negate any environmental benefits of self-driving cars if a large enough number of people begin driving personal vehicles more frequently.[77]

Automation of homes and home appliances is also thought to impact the environment, but the benefits of these features are also questioned. A study of energy consumption of automated homes in Finland showed that smart homes could reduce energy consumption by monitoring levels of consumption in different areas of the home and adjusting consumption to reduce energy leaks (e.g. automatically reducing consumption during the nighttime when activity is low). This study, along with others, indicated that the smart home's ability to monitor and adjust consumption levels would reduce unnecessary energy usage. However, new research suggests that smart homes might not be as efficient as non-automated homes. A more recent study has indicated that, while monitoring and adjusting consumption levels do decrease unnecessary energy use, this process requires monitoring systems that also consume a significant amount of energy. This study suggested that the energy required to run these systems is so much so that it negates any benefits of the systems themselves, resulting in little to no ecological benefit.[78]

Convertibility and turnaround time

Another major shift in automation is the increased demand for flexibility and convertibility in manufacturing processes. Manufacturers are increasingly demanding the ability to easily switch from manufacturing Product A to manufacturing Product B without having to completely rebuild the production lines. Flexibility and distributed processes have led to the introduction of Automated Guided Vehicles with Natural Features Navigation.

Digital electronics helped too. Former analog-based instrumentation was replaced by digital equivalents which can be more accurate and flexible, and offer greater scope for more sophisticated configuration, parametrization, and operation. This was accompanied by the fieldbus revolution which provided a networked (i.e. a single cable) means of communicating between control systems and field-level instrumentation, eliminating hard-wiring.

Discrete manufacturing plants adopted these technologies fast. The more conservative process industries with their longer plant life cycles have been slower to adopt and analog-based measurement and control still dominate. The growing use of Industrial Ethernet on the factory floor is pushing these trends still further, enabling manufacturing plants to be integrated more tightly within the enterprise, via the internet if necessary. Global competition has also increased demand for Reconfigurable Manufacturing Systems.

Automation tools

Engineers can now have numerical control over automated devices. The result has been a rapidly expanding range of applications and human activities. Computer-aided technologies (or CAx) now serve as the basis for mathematical and organizational tools used to create complex systems. Notable examples of CAx include computer-aided design (CAD software) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM software). The improved design, analysis, and manufacture of products enabled by CAx has been beneficial for industry.[79]

Information technology, together with industrial machinery and processes, can assist in the design, implementation, and monitoring of control systems. One example of an industrial control system is a programmable logic controller (PLC). PLCs are specialized hardened computers which are frequently used to synchronize the flow of inputs from (physical) sensors and events with the flow of outputs to actuators and events.[80]

Human-machine interfaces (HMI) or computer human interfaces (CHI), formerly known as man-machine interfaces, are usually employed to communicate with PLCs and other computers. Service personnel who monitor and control through HMIs can be called by different names. In the industrial process and manufacturing environments, they are called operators or something similar. In boiler houses and central utility departments, they are called stationary engineers.[81]

Different types of automation tools exist:

- ANN – Artificial neural network

- DCS – Distributed control system

- HMI – Human machine interface

- RPA – Robotic process automation

- SCADA – Supervisory control and data acquisition

- PLC – Programmable logic controller

- Instrumentation

- Motion control

- Robotics

Host simulation software (HSS) is a commonly used testing tool that is used to test the equipment software. HSS is used to test equipment performance concerning factory automation standards (timeouts, response time, processing time).[82]

Cognitive automation

Cognitive automation, as a subset of AI, is an emerging genus of automation enabled by cognitive computing. Its primary concern is the automation of clerical tasks and workflows that consist of structuring unstructured data.[83] Cognitive automation relies on multiple disciplines: natural language processing, real-time computing, machine learning algorithms, big data analytics, and evidence-based learning.[84]

According to Deloitte, cognitive automation enables the replication of human tasks and judgment "at rapid speeds and considerable scale."[85] Such tasks include:

- Document redaction

- Data extraction and document synthesis / reporting

- Contract management

- Natural language search

- Customer, employee, and stakeholder onboarding

- Manual activities and verifications

- Follow-up and email communications

Recent and emerging applications

Automated power production

Technologies like solar panels, wind turbines, and other renewable energy sources—together with smart grids, micro-grids, battery storage—can automate power production.

Agricultural production

Many agricultural operations are automated with machinery and equipment to improve their diagnosis, decision-making and/or performing. Agricultural automation can relieve the drudgery of agricultural work, improve the timeliness and precision of agricultural operations, raise productivity and resource-use efficiency, build resilience, and improve food quality and safety.[86] Increased productivity can free up labour, allowing agricultural households to spend more time elsewhere.[87]

The technological evolution in agriculture has resulted in progressive shifts to digital equipment and robotics.[86] Motorized mechanization using engine power automates the performance of agricultural operations such as ploughing and milking.[88] With digital automation technologies, it also becomes possible to automate diagnosis and decision-making of agricultural operations.[86] For example, autonomous crop robots can harvest and seed crops, while drones can gather information to help automate input application.[87] Precision agriculture often employs such automation technologies[87]

Motorized mechanization has generally increased in recent years.[89] Sub-Saharan Africa is the only region where the adoption of motorized mechanization has stalled over the past decades.[90][87]

Automation technologies are increasingly used for managing livestock, though evidence on adoption is lacking. Global automatic milking system sales have increased over recent years,[91] but adoption is likely mostly in Northern Europe,[92] and likely almost absent in low- and middle-income countries.[93][87] Automated feeding machines for both cows and poultry also exist, but data and evidence regarding their adoption trends and drivers is likewise scarce.[87][89]

Retail

Many supermarkets and even smaller stores are rapidly introducing self-checkout systems reducing the need for employing checkout workers. In the U.S., the retail industry employs 15.9 million people as of 2017 (around 1 in 9 Americans in the workforce). Globally, an estimated 192 million workers could be affected by automation according to research by Eurasia Group.[94]

Online shopping could be considered a form of automated retail as the payment and checkout are through an automated online transaction processing system, with the share of online retail accounting jumping from 5.1% in 2011 to 8.3% in 2016. However, two-thirds of books, music, and films are now purchased online. In addition, automation and online shopping could reduce demands for shopping malls, and retail property, which in the USA is currently estimated to account for 31% of all commercial property or around 7 billion square feet (650 million square metres). Amazon has gained much of the growth in recent years for online shopping, accounting for half of the growth in online retail in 2016.[94] Other forms of automation can also be an integral part of online shopping, for example, the deployment of automated warehouse robotics such as that applied by Amazon using Kiva Systems.

Food and drink

The food retail industry has started to apply automation to the ordering process; McDonald's has introduced touch screen ordering and payment systems in many of its restaurants, reducing the need for as many cashier employees.[95] The University of Texas at Austin has introduced fully automated cafe retail locations.[96] Some Cafes and restaurants have utilized mobile and tablet "apps" to make the ordering process more efficient by customers ordering and paying on their device.[97] Some restaurants have automated food delivery to tables of customers using a Conveyor belt system. The use of robots is sometimes employed to replace waiting staff.[98]

Construction

Automation in construction is the combination of methods, processes, and systems that allow for greater machine autonomy in construction activities. Construction automation may have multiple goals, including but not limited to, reducing jobsite injuries, decreasing activity completion times, and assisting with quality control and quality assurance.[99]

Mining

Automated mining involves the removal of human labor from the mining process.[100] The mining industry is currently in the transition towards automation. Currently, it can still require a large amount of human capital, particularly in the third world where labor costs are low so there is less incentive for increasing efficiency through automation.

Video surveillance

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) started the research and development of automated visual surveillance and monitoring (VSAM) program, between 1997 and 1999, and airborne video surveillance (AVS) programs, from 1998 to 2002. Currently, there is a major effort underway in the vision community to develop a fully-automated tracking surveillance system. Automated video surveillance monitors people and vehicles in real-time within a busy environment. Existing automated surveillance systems are based on the environment they are primarily designed to observe, i.e., indoor, outdoor or airborne, the number of sensors that the automated system can handle and the mobility of sensors, i.e., stationary camera vs. mobile camera. The purpose of a surveillance system is to record properties and trajectories of objects in a given area, generate warnings or notify the designated authorities in case of occurrence of particular events.[101]

Highway systems

As demands for safety and mobility have grown and technological possibilities have multiplied, interest in automation has grown. Seeking to accelerate the development and introduction of fully automated vehicles and highways, the U.S. Congress authorized more than $650 million over six years for intelligent transport systems (ITS) and demonstration projects in the 1991 Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA). Congress legislated in ISTEA that:[102]

[T]he Secretary of Transportation shall develop an automated highway and vehicle prototype from which future fully automated intelligent vehicle-highway systems can be developed. Such development shall include research in human factors to ensure the success of the man-machine relationship. The goal of this program is to have the first fully automated highway roadway or an automated test track in operation by 1997. This system shall accommodate the installation of equipment in new and existing motor vehicles.

Full automation commonly defined as requiring no control or very limited control by the driver; such automation would be accomplished through a combination of sensor, computer, and communications systems in vehicles and along the roadway. Fully automated driving would, in theory, allow closer vehicle spacing and higher speeds, which could enhance traffic capacity in places where additional road building is physically impossible, politically unacceptable, or prohibitively expensive. Automated controls also might enhance road safety by reducing the opportunity for driver error, which causes a large share of motor vehicle crashes. Other potential benefits include improved air quality (as a result of more-efficient traffic flows), increased fuel economy, and spin-off technologies generated during research and development related to automated highway systems.[103]

Waste management

Automated waste collection trucks prevent the need for as many workers as well as easing the level of labor required to provide the service.[104]

Business process

Business process automation (BPA) is the technology-enabled automation of complex business processes.[105] It can help to streamline a business for simplicity, achieve digital transformation, increase service quality, improve service delivery or contain costs. BPA consists of integrating applications, restructuring labor resources and using software applications throughout the organization. Robotic process automation (RPA; or RPAAI for self-guided RPA 2.0) is an emerging field within BPA and uses AI. BPAs can be implemented in a number of business areas including marketing, sales and workflow.

Home

Home automation (also called domotics) designates an emerging practice of increased automation of household appliances and features in residential dwellings, particularly through electronic means that allow for things impracticable, overly expensive or simply not possible in recent past decades. The rise in the usage of home automation solutions has taken a turn reflecting the increased dependency of people on such automation solutions. However, the increased comfort that gets added through these automation solutions is remarkable.[106]

Laboratory

Automation is essential for many scientific and clinical applications.[107] Therefore, automation has been extensively employed in laboratories. From as early as 1980 fully automated laboratories have already been working.[108] However, automation has not become widespread in laboratories due to its high cost. This may change with the ability of integrating low-cost devices with standard laboratory equipment.[109][110] Autosamplers are common devices used in laboratory automation.

Logistics automation

Logistics automation is the application of computer software or automated machinery to improve the efficiency of logistics operations. Typically this refers to operations within a warehouse or distribution center, with broader tasks undertaken by supply chain engineering systems and enterprise resource planning systems.

Industrial automation

Industrial automation deals primarily with the automation of manufacturing, quality control, and material handling processes. General-purpose controllers for industrial processes include programmable logic controllers, stand-alone I/O modules, and computers. Industrial automation is to replace the human action and manual command-response activities with the use of mechanized equipment and logical programming commands. One trend is increased use of machine vision[111] to provide automatic inspection and robot guidance functions, another is a continuing increase in the use of robots. Industrial automation is simply required in industries.

Energy efficiency in industrial processes has become a higher priority. Semiconductor companies like Infineon Technologies are offering 8-bit micro-controller applications for example found in motor controls, general purpose pumps, fans, and ebikes to reduce energy consumption and thus increase efficiency.

Industrial Automation and Industry 4.0

The rise of industrial automation is directly tied to the “Fourth Industrial Revolution”, which is better known now as Industry 4.0. Originating from Germany, Industry 4.0 encompasses numerous devices, concepts, and machines,[112] as well as the advancement of the industrial internet of things (IIoT). An "Internet of Things is a seamless integration of diverse physical objects in the Internet through a virtual representation."[113] These new revolutionary advancements have drawn attention to the world of automation in an entirely new light and shown ways for it to grow to increase productivity and efficiency in machinery and manufacturing facilities. Industry 4.0 works with the IIoT and software/hardware to connect in a way that (through communication technologies) add enhancements and improve manufacturing processes. Being able to create smarter, safer, and more advanced manufacturing is now possible with these new technologies. It opens up a manufacturing platform that is more reliable, consistent, and efficient than before. Implementation of systems such as SCADA is an example of software that takes place in Industrial Automation today. SCADA is a supervisory data collection software, just one of the many used in Industrial Automation.[114] Industry 4.0 vastly covers many areas in manufacturing and will continue to do so as time goes on.[112]

Industrial robotics

Industrial robotics is a sub-branch in industrial automation that aids in various manufacturing processes. Such manufacturing processes include machining, welding, painting, assembling and material handling to name a few.[115] Industrial robots use various mechanical, electrical as well as software systems to allow for high precision, accuracy and speed that far exceed any human performance. The birth of industrial robots came shortly after World War II as the U.S. saw the need for a quicker way to produce industrial and consumer goods.[116] Servos, digital logic and solid-state electronics allowed engineers to build better and faster systems and over time these systems were improved and revised to the point where a single robot is capable of running 24 hours a day with little or no maintenance. In 1997, there were 700,000 industrial robots in use, the number has risen to 1.8M in 2017[117] In recent years, AI with robotics is also used in creating an automatic labeling solution, using robotic arms as the automatic label applicator, and AI for learning and detecting the products to be labelled.[118]

Programmable Logic Controllers

Industrial automation incorporates programmable logic controllers in the manufacturing process. Programmable logic controllers (PLCs) use a processing system which allows for variation of controls of inputs and outputs using simple programming. PLCs make use of programmable memory, storing instructions and functions like logic, sequencing, timing, counting, etc. Using a logic-based language, a PLC can receive a variety of inputs and return a variety of logical outputs, the input devices being sensors and output devices being motors, valves, etc. PLCs are similar to computers, however, while computers are optimized for calculations, PLCs are optimized for control tasks and use in industrial environments. They are built so that only basic logic-based programming knowledge is needed and to handle vibrations, high temperatures, humidity, and noise. The greatest advantage PLCs offer is their flexibility. With the same basic controllers, a PLC can operate a range of different control systems. PLCs make it unnecessary to rewire a system to change the control system. This flexibility leads to a cost-effective system for complex and varied control systems.[119]

PLCs can range from small "building brick" devices with tens of I/O in a housing integral with the processor, to large rack-mounted modular devices with a count of thousands of I/O, and which are often networked to other PLC and SCADA systems.

They can be designed for multiple arrangements of digital and analog inputs and outputs (I/O), extended temperature ranges, immunity to electrical noise, and resistance to vibration and impact. Programs to control machine operation are typically stored in battery-backed-up or non-volatile memory.

It was from the automotive industry in the USA that the PLC was born. Before the PLC, control, sequencing, and safety interlock logic for manufacturing automobiles was mainly composed of relays, cam timers, drum sequencers, and dedicated closed-loop controllers. Since these could number in the hundreds or even thousands, the process for updating such facilities for the yearly model change-over was very time-consuming and expensive, as electricians needed to individually rewire the relays to change their operational characteristics.

When digital computers became available, being general-purpose programmable devices, they were soon applied to control sequential and combinatorial logic in industrial processes. However, these early computers required specialist programmers and stringent operating environmental control for temperature, cleanliness, and power quality. To meet these challenges, the PLC was developed with several key attributes. It would tolerate the shop-floor environment, it would support discrete (bit-form) input and output in an easily extensible manner, it would not require years of training to use, and it would permit its operation to be monitored. Since many industrial processes have timescales easily addressed by millisecond response times, modern (fast, small, reliable) electronics greatly facilitate building reliable controllers, and performance could be traded off for reliability.[120]

Agent-assisted automation

Agent-assisted automation refers to automation used by call center agents to handle customer inquiries. The key benefit of agent-assisted automation is compliance and error-proofing. Agents are sometimes not fully trained or they forget or ignore key steps in the process. The use of automation ensures that what is supposed to happen on the call actually does, every time. There are two basic types: desktop automation and automated voice solutions.

Desktop automation refers to software programming that makes it easier for the call center agent to work across multiple desktop tools. The automation would take the information entered into one tool and populate it across the others so it did not have to be entered more than once, for example.

Automated voice solutions allow the agents to remain on the line while disclosures and other important information is provided to customers in the form of pre-recorded audio files. Specialized applications of these automated voice solutions enable the agents to process credit cards without ever seeing or hearing the credit card numbers or CVV codes.[121]

Control

Open-loop and closed-loop

Fundamentally, there are two types of control loop: open-loop control (feedforward), and closed-loop control (feedback).

In open-loop control, the control action from the controller is independent of the "process output" (or "controlled process variable"). A good example of this is a central heating boiler controlled only by a timer, so that heat is applied for a constant time, regardless of the temperature of the building. The control action is the switching on/off of the boiler, but the controlled variable should be the building temperature, but is not because this is open-loop control of the boiler, which does not give closed-loop control of the temperature.

In closed loop control, the control action from the controller is dependent on the process output. In the case of the boiler analogy this would include a thermostat to monitor the building temperature, and thereby feed back a signal to ensure the controller maintains the building at the temperature set on the thermostat. A closed loop controller therefore has a feedback loop which ensures the controller exerts a control action to give a process output the same as the "reference input" or "set point". For this reason, closed loop controllers are also called feedback controllers.[122]

The definition of a closed loop control system according to the British Standard Institution is "a control system possessing monitoring feedback, the deviation signal formed as a result of this feedback being used to control the action of a final control element in such a way as to tend to reduce the deviation to zero."[123]

Likewise; "A Feedback Control System is a system which tends to maintain a prescribed relationship of one system variable to another by comparing functions of these variables and using the difference as a means of control."[124]Discrete control (on/off)

One of the simplest types of control is on-off control. An example is a thermostat used on household appliances which either open or close an electrical contact. (Thermostats were originally developed as true feedback-control mechanisms rather than the on-off common household appliance thermostat.)

Sequence control, in which a programmed sequence of discrete operations is performed, often based on system logic that involves system states. An elevator control system is an example of sequence control.

PID controller

A proportional–integral–derivative controller (PID controller) is a control loop feedback mechanism (controller) widely used in industrial control systems.

In a PID loop, the controller continuously calculates an error value as the difference between a desired setpoint and a measured process variable and applies a correction based on proportional, integral, and derivative terms, respectively (sometimes denoted P, I, and D) which give their name to the controller type.

The theoretical understanding and application date from the 1920s, and they are implemented in nearly all analog control systems; originally in mechanical controllers, and then using discrete electronics and latterly in industrial process computers.

Sequential control and logical sequence or system state control

Sequential control may be either to a fixed sequence or to a logical one that will perform different actions depending on various system states. An example of an adjustable but otherwise fixed sequence is a timer on a lawn sprinkler.

States refer to the various conditions that can occur in a use or sequence scenario of the system. An example is an elevator, which uses logic based on the system state to perform certain actions in response to its state and operator input. For example, if the operator presses the floor n button, the system will respond depending on whether the elevator is stopped or moving, going up or down, or if the door is open or closed, and other conditions.[125]

Early development of sequential control was relay logic, by which electrical relays engage electrical contacts which either start or interrupt power to a device. Relays were first used in telegraph networks before being developed for controlling other devices, such as when starting and stopping industrial-sized electric motors or opening and closing solenoid valves. Using relays for control purposes allowed event-driven control, where actions could be triggered out of sequence, in response to external events. These were more flexible in their response than the rigid single-sequence cam timers. More complicated examples involved maintaining safe sequences for devices such as swing bridge controls, where a lock bolt needed to be disengaged before the bridge could be moved, and the lock bolt could not be released until the safety gates had already been closed.

The total number of relays and cam timers can number into the hundreds or even thousands in some factories. Early programming techniques and languages were needed to make such systems manageable, one of the first being ladder logic, where diagrams of the interconnected relays resembled the rungs of a ladder. Special computers called programmable logic controllers were later designed to replace these collections of hardware with a single, more easily re-programmed unit.

In a typical hard-wired motor start and stop circuit (called a control circuit) a motor is started by pushing a "Start" or "Run" button that activates a pair of electrical relays. The "lock-in" relay locks in contacts that keep the control circuit energized when the push-button is released. (The start button is a normally open contact and the stop button is a normally closed contact.) Another relay energizes a switch that powers the device that throws the motor starter switch (three sets of contacts for three-phase industrial power) in the main power circuit. Large motors use high voltage and experience high in-rush current, making speed important in making and breaking contact. This can be dangerous for personnel and property with manual switches. The "lock-in" contacts in the start circuit and the main power contacts for the motor are held engaged by their respective electromagnets until a "stop" or "off" button is pressed, which de-energizes the lock in relay.[126]

Commonly interlocks are added to a control circuit. Suppose that the motor in the example is powering machinery that has a critical need for lubrication. In this case, an interlock could be added to ensure that the oil pump is running before the motor starts. Timers, limit switches, and electric eyes are other common elements in control circuits.

Solenoid valves are widely used on compressed air or hydraulic fluid for powering actuators on mechanical components. While motors are used to supply continuous rotary motion, actuators are typically a better choice for intermittently creating a limited range of movement for a mechanical component, such as moving various mechanical arms, opening or closing valves, raising heavy press-rolls, applying pressure to presses.

Computer control

Computers can perform both sequential control and feedback control, and typically a single computer will do both in an industrial application. Programmable logic controllers (PLCs) are a type of special-purpose microprocessor that replaced many hardware components such as timers and drum sequencers used in relay logic–type systems. General-purpose process control computers have increasingly replaced stand-alone controllers, with a single computer able to perform the operations of hundreds of controllers. Process control computers can process data from a network of PLCs, instruments, and controllers to implement typical (such as PID) control of many individual variables or, in some cases, to implement complex control algorithms using multiple inputs and mathematical manipulations. They can also analyze data and create real-time graphical displays for operators and run reports for operators, engineers, and management.

Control of an automated teller machine (ATM) is an example of an interactive process in which a computer will perform a logic-derived response to a user selection based on information retrieved from a networked database. The ATM process has similarities with other online transaction processes. The different logical responses are called scenarios. Such processes are typically designed with the aid of use cases and flowcharts, which guide the writing of the software code. The earliest feedback control mechanism was the water clock invented by Greek engineer Ctesibius (285–222 BC).

See also

- Automate This

- Automated storage and retrieval system

- Automation engineering

- Automation technician

- Cognitive computing

- Control engineering

- Critique of work

- Cybernetics

- Data-driven control system

- Dirty, dangerous and demeaning

- Feedforward control

- Fully Automated Luxury Communism

- Futures studies

- The Human Use of Human Beings

- Industrial Revolution

- Industry 4.0

- Intelligent automation

- Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work

- Machine to machine

- Mobile manipulator

- Multi-agent system

- Post-work society

- Process control

- Productivity improving technologies

- The Right to Be Lazy

- Right to repair

- Robot tax

- Robotic process automation

- Semi-automation

- Technological unemployment

- The War on Normal People

References

Citations

- Groover, Mikell (2014). Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing: Materials, Processes, and Systems.

- Agrawal, Ajay; Gans, Joshua S.; Goldfarb, Avi (2023). "Do we want less automation?". Science. 381 (6654): 155–158. Bibcode:2023Sci...381..155A. doi:10.1126/science.adh9429. PMID 37440634.

- Lyshevski, S.E. Electromechanical Systems and Devices 1st Edition. CRC Press, 2008. ISBN 1420069721.

- Lamb, Frank. Industrial Automation: Hands On (English Edition). NC, McGraw-Hill Education, 2013. ISBN 978-0071816458

- Rifkin, Jeremy (1995). The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era. Putnam Publishing Group. pp. 66, 75. ISBN 978-0-87477-779-6.

- Bennett 1993.

- The Changing Nature of Work (Report). The World Bank. 2019.

- Dashevsky, Evan (8 November 2017). "How Robots Caused Brexit and the Rise of Donald Trump". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017.

- Torrance, Jack (25 July 2017). "Robots for Trump: Did automation swing the US election?". Management Today.

- Harris, John (29 December 2016). "The lesson of Trump and Brexit: a society too complex for its people risks everything | John Harris". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

- Darrell West (18 April 2018). "Will robots and AI take your job? The economic and political consequences of automation". Brookings Institution.

- Clare Byrne (7 December 2016). "'People are lost': Voters in France's 'Trumplands' look to far right". The Local.fr.

- Guarnieri, M. (2010). "The Roots of Automation Before Mechatronics". IEEE Ind. Electron. M. 4 (2): 42–43. doi:10.1109/MIE.2010.936772. hdl:11577/2424833. S2CID 24885437.

- Ahmad Y Hassan, Transfer Of Islamic Technology To The West, Part II: Transmission Of Islamic Engineering Archived 18 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- J. Adamy & A. Flemming (November 2004), "Soft variable-structure controls: a survey" (PDF), Automatica, 40 (11): 1821–1844, doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2004.05.017, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2021, retrieved 12 July 2019

- Otto Mayr (1970). The Origins of Feedback Control, MIT Press.

- Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, p. 64-69.

- "Charting the Globe and Tracking the Heavens". Princeton.edu.

- Bellman, Richard E. (8 December 2015). Adaptive Control Processes: A Guided Tour. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400874668.

- Bennett, S. (1979). A History of Control Engineering 1800–1930. London: Peter Peregrinus Ltd. pp. 47, 266. ISBN 978-0-86341-047-5.

- Bennett 1979

- Bronowski, Jacob (1990) [1973]. The Ascent of Man. London: BBC Books. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-563-20900-3.

- Liu, Tessie P. (1994). The Weaver's Knot: The Contradictions of Class Struggle and Family Solidarity in Western France, 1750–1914. Cornell University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8014-8019-5.

- Jacobson, Howard B.; Joseph S. Roueek (1959). Automation and Society. New York, NY: Philosophical Library. p. 8.

- Hounshell, David A. (1984), From the American System to Mass Production, 1800–1932: The Development of Manufacturing Technology in the United States, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-2975-8, LCCN 83016269, OCLC 1104810110

- Partington, Charles Frederick (1 January 1826). "A course of lectures on the Steam Engine, delivered before the Members of the London Mechanics' Institution ... To which is subjoined, a copy of the rare ... work on Steam Navigation, originally published by J. Hulls in 1737. Illustrated by ... engravings".

- Britain), Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce (Great (1 January 1814). "Transactions of the Society Instituted at London for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bennett 1993, pp. 31

- Field, Alexander J. (2011). A Great Leap Forward: 1930s Depression and U.S. Economic Growth. New Haven, London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15109-1.

- "INTERKAMA 1960 – Dusseldorf Exhibition of Automation and Instruments" (PDF). Wireless World. 66 (12): 588–589. December 1960.

[…] Another point noticed was the widespread use of small-package solid-state logic (such as "and," "or," "not") and instrumentation (timers, amplifiers, etc.) units. There would seem to be a good case here for the various manufacturers to standardise practical details such as mounting, connections and power supplies so that a Siemens "Simatic," say, is directly interchangeable with an Ateliers des Constructions Electronique de Charleroi "Logacec," a Telefunken "Logistat," or a Mullard "Norbit" or "Combi-element." […]

- "les relais statiques Norbit". Revue MBLE (in French). September 1962. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018.

- Estacord – Das universelle Bausteinsystem für kontaktlose Steuerungen (Catalog) (in German). Herxheim/Pfalz, Germany: Akkord-Radio GmbH.

- Klingelnberg, W. Ferdinand (2013) [1967, 1960, 1939]. Pohl, Fritz; Reindl, Rudolf (eds.). Technisches Hilfsbuch (in German) (softcover reprint of 15th hardcover ed.). Springer-Verlag. p. 135. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-88367-5. ISBN 978-3-64288368-2. LCCN 67-23459. 0512.

- Parr, E. Andrew (1993) [1984]. Logic Designer's Handbook: Circuits and Systems (revised 2nd ed.). B.H. Newnes / Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd. / Reed International Books. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-7506-0535-9.

- Weißel, Ralph; Schubert, Franz (7 March 2013) [1995, 1990]. "4.1. Grundschaltungen mit Bipolar- und Feldeffekttransistoren". Digitale Schaltungstechnik. Springer-Lehrbuch (in German) (reprint of 2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. p. 116. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78387-6. ISBN 978-3-540-57012-7.

- Walker, Mark John (8 September 2012). The Programmable Logic Controller: its prehistory, emergence and application (PDF) (PhD thesis). Department of Communication and Systems Faculty of Mathematics, Computing and Technology: The Open University. pp. 223, 269, 308. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2018.

- Rifkin 1995

- Jerome, Harry (1934). Mechanization in Industry, National Bureau of Economic Research (PDF).

- Constable, George; Somerville, Bob (1964). A Century of Innovation: Twenty Engineering Achievements That Transformed Our Lives. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0309089081.

- "The American Society of Mechanical Engineers Designates the Owens "AR" Bottle Machine as an International Historic Engineering Landmark". 1983. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- Bennett 1993, pp. 7

- Landes, David. S. (1969). The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. Cambridge, New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. p. 475. ISBN 978-0-521-09418-4.

- Bennett 1993, pp. 65Note 1

- Musson; Robinson (1969). Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802016379.

- Lamb, Frank (2013). Industrial Automation: Hands on. pp. 1–4.

- Arnzt, Melanie (14 May 2016). "The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS". ProQuest 1790436902.

- "Process automation, retrieved on 20.02.2010". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013.

- Bartelt, Terry. Industrial Automated Systems: Instrumentation and Motion Control. Cengage Learning, 2010.

- Bainbridge, Lisanne (November 1983). "Ironies of automation". Automatica. 19 (6): 775–779. doi:10.1016/0005-1098(83)90046-8. S2CID 12667742.

- Kaufman, Josh. "Paradox of Automation – The Personal MBA". Personalmba.com.

- "Children of the Magenta (Automation Paradox, pt. 1) – 99% Invisible". 99percentinvisible.org. 23 June 2015.

- Artificial Intelligence and Robotics and Their Impact on the Workplace.

- Schaupp, Simon (23 May 2022). "COVID‐19, economic crises and digitalisation: How algorithmic management became an alternative to automation". New Technology, Work and Employment. 38 (2): 311–329. doi:10.1111/ntwe.12246. ISSN 0268-1072. PMC 9347406. PMID 35936383.

- Benanav, Aaron (2020). Automation and the future of work. London. ISBN 978-1-83976-129-4. OCLC 1147891672.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Luddite". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Romero, Simon (31 December 2018). "Wielding Rocks and Knives, Arizonans Attack Self-Driving Cars". The New York Times.

- Goodman, Peter S. (27 December 2017). "The Robots are Coming, and Sweden is Fine". The New York Times.

- Frey, C. B.; Osborne, M.A. (17 September 2013). "THE FUTURE OF EMPLOYMENT: HOW SUSCEPTIBLE ARE JOBS TO COMPUTERISATION?" (PDF).

- Susskind, Richard; Susskind, Daniel (11 October 2016). "Technology Will Replace Many Doctors, Lawyers, and Other Professionals". Harvard Business Review.

- "Death of the American Trucker". Rollingstone.com. 2 January 2018.

- "Silicon Valley luminaries are busily preparing for when robots take over". Mashable.com. 6 August 2017.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik (2014). The second machine age : work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. Andrew McAfee (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-393-23935-5. OCLC 867423744.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Acemoglu, Daron; Restrepo, Pascual (2020). "Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy. 128 (6): 2188–2244. doi:10.1086/705716. hdl:1721.1/130324. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 201370532.

- Carl Benedikt Frey; Michael Osborne (September 2013). "The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?" (publication). Oxford Martin School.

- Chui, Michael; James Manyika; Mehdi Miremadi (November 2015). "Four fundamentals of workplace automation". McKinsey Quarterly. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015.

Very few occupations will be automated in their entirety in the near or medium term. Rather, certain activities are more likely to be automated....

- Steve Lohr (6 November 2015). "Automation Will Change Jobs More Than Kill Them". The New York Times.

technology-driven automation will affect almost every occupation and can change work, according to new research from McKinsey

- Arntz er al (Summer 2017). "Future of work". Economic Lettets.

- Autor, David H. (2015). "Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 29 (3): 3–30. doi:10.1257/jep.29.3.3. hdl:1721.1/109476.

- McGaughey, Ewan (10 January 2018). "Will Robots Automate Your Job Away? Full Employment, Basic Income, and Economic Democracy". SSRN 3044448.

- Arntzi, Melanie; Terry Gregoryi; Ulrich Zierahni (2016). "The Risk of Automation for Jobs in OECD Countries". OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers (189). doi:10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en.

- Executive Office of the President. December 2016. "Artificial Intelligence, Automation and the Economy." Pp. 2, 13–19.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Restrepo, Pascual. "Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets". Archived from the original on 3 April 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Saint-Paul, Gilles (21 July 2008). Innovation and Inequality: How Does Technical Progress Affect Workers?. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691128306.

- McKinsey Global Institute (December 2017). Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained: Workforce Transitions in a Time of Automation. Mckinsey & Company. pp. 1–20.

- "Lights out manufacturing and its impact on society". RCR Wireless News. 10 August 2016.

- "Checklist for Lights-Out Manufacturing". CNC machine tools. 4 September 2017.

- "Self-Driving Cars Could Help Save the Environment—Or Ruin It. It Depends on Us". Time.com.

- Louis, Jean-Nicolas; Calo, Antonio; Leiviskä, Kauko; Pongrácz, Eva (2015). "Environmental Impacts and Benefits of Smart Home Automation: Life Cycle Assessment of Home Energy Management System" (PDF). IFAC-Papers on Line. 48: 880. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.05.158.

- Werner Dankwort, C; Weidlich, Roland; Guenther, Birgit; Blaurock, Joerg E (2004). "Engineers' CAx education—it's not only CAD". Computer-Aided Design. 36 (14): 1439. doi:10.1016/j.cad.2004.02.011.

- "Automation - Definitions from Dictionary.com". dictionary.reference.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- "Stationary Engineers and Boiler Operators". Archived from the original on 30 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2006.

- "Effective host stimulation" (PDF). www.hcltech.com.

- "Automate Complex Workflows Using Tactical Cognitive Computing: Coseer". thesiliconreview.com. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- "What is Cognitive Automation – An Introduction". 10xDS. 19 August 2019.

- "Cognitive automation: Streamlining knowledge processes | Deloitte US". Deloitte United States. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- In Brief to The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. Leveraging automation in agriculture for transforming agrifood systems. 2022. doi:10.4060/cc2459en. ISBN 978-92-5-137005-6. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - The State of Food and Agriculture 2022.Leveraging agricultural automation for transforming agrifood systems. 2022. doi:10.4060/cb9479en. ISBN 978-92-5-136043-9. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Santos Valle, S.; Kienzle, J. (2020). Agriculture 4.0 – Agricultural robotics and automated equipment for sustainable crop production. Rome: FAO.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "FAOSTAT: Discontinued archives and data series: Machinery". FAO. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- Daum, Thomas; Birner, Regina (1 September 2020). "Agricultural mechanization in Africa: Myths, realities and an emerging research agenda". Global Food Security. 26: 100393. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100393. ISSN 2211-9124. S2CID 225280050.

- "Global milking robots market size by type, by herd size, by geographic scope and forecast". Verified Market Research. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- Rodenburg, Jack (2017). "Robotic milking: Technology, farm design, and effects on work flow". Journal of Dairy Science. 100 (9): 7729–7738. doi:10.3168/jds.2016-11715. ISSN 0022-0302. PMID 28711263. S2CID 11934286.

- Economics of adoption for digital automated technologies in agriculture. Background paper for The State of Food and Agriculture 2022. 2022. doi:10.4060/cc2624en. ISBN 978-92-5-137080-3. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - "The decline of established American retailing threatens jobs". The Economist. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "McDonald’s automation a sign of declining service sector employment – IT Business". 19 September 2013. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013.

- Automation Comes To The Coffeehouse With Robotic Baristas. Singularity Hub. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- New Pizza Express app lets diners pay bill using iPhone. Bighospitality.co.uk. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- Wheelie: Toshiba's new robot is cute, autonomous and maybe even useful (video). TechCrunch (12 March 2010). Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- "The impact and opportunities of automation in construction". McKinsey & Company. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- "Rio to trial automated mining." The Australian.

- Javed, O, & Shah, M. (2008). Automated multi-camera surveillance. City of Publication: Springer-Verlag New York Inc.

- Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act 1991, part B, Section 6054(b)

- Menzies, Thomas R., ed. 1998. "National Automated Highway System Research Program: A Review." Transportation Research Board Special Report 253. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. pp. 2–50.

- Hepker, Aaron. (27 November 2012) Automated Garbage Trucks Hitting Cedar Rapids Streets | KCRG-TV9 | Cedar Rapids, Iowa News, Sports, and Weather | Local News Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Kcrg.com. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- "Business Process Automation – Gartner IT Glossary". Gartner.com. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- "Smart & Intelligent Home Automation Solutions". 15 May 2018.

- Carvalho, Matheus (2017). Practical Laboratory Automation: Made Easy with AutoIt. Wiley VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-34158-0.

- Boyd, James (18 January 2002). "Robotic Laboratory Automation". Science. 295 (5554): 517–518. doi:10.1126/science.295.5554.517. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11799250. S2CID 108766687.

- Carvalho, Matheus C. (1 August 2013). "Integration of Analytical Instruments with Computer Scripting". Journal of Laboratory Automation. 18 (4): 328–333. doi:10.1177/2211068213476288. ISSN 2211-0682. PMID 23413273.

- Pearce, Joshua M. (1 January 2014). "Introduction to Open-Source Hardware for Science". Chapter 1 - Introduction to Open-Source Hardware for Science. Boston: Elsevier. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-410462-4.00001-9. ISBN 9780124104624.

- "What is machine vision, and how can it help?". Control Engineering. 6 December 2018.

- Kamarul Bahrin, Mohd Aiman; Othman, Mohd Fauzi; Nor Azli, Nor Hayati; Talib, Muhamad Farihin (2016). "Industry 4.0: A Review on Industrial Automation and Robotic". Jurnal Teknologi. 78 (6–13). doi:10.11113/jt.v78.9285.

- Jung, Markus; Reinisch, Christian; Kastner, Wolfgang (2012). "Integrating Building Automation Systems and IPv6 in the Internet of Things". 2012 Sixth International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing. pp. 683–688. doi:10.1109/IMIS.2012.134. ISBN 978-1-4673-1328-5. S2CID 11670295.

- Pérez-López, Esteban (2015). "Los sistemas SCADA en la automatización industrial". Revista Tecnología en Marcha. 28 (4): 3. doi:10.18845/tm.v28i4.2438.

- Shell, Richard (2000). Handbook of Industrial Automation. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 9780824703738.

- Kurfess, Thomas (2005). Robotics and Automation Handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 5. ISBN 9780849318047.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. "Managing man and machine". PwC. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "AI Automatic Label Applicator & Labelling System". Milliontech. 18 January 2018.

- Bolten, William (2009). Programmable Logic Controllers (5th ed.). p. 3.

- E. A. Parr, Industrial Control Handbook, Industrial Press Inc., 1999 ISBN 0-8311-3085-7