Automotive industry

The automotive industry comprises a wide range of companies and organizations involved in the design, development, manufacturing, marketing, selling, repairing, and modification of motor vehicles.[1] It is one of the world's largest industries by revenue (from 16% such as in France up to 40% to countries like Slovakia).[2]

The word automotive comes from the Greek autos (self), and Latin motivus (of motion), referring to any form of self-powered vehicle. This term, as proposed by Elmer Sperry[3] (1860–1930), first came into use with reference to automobiles in 1898.

History

The automotive industry began in the 1860s with hundreds of manufacturers that pioneered the horseless carriage. Early car manufacturing involved manual assembly by a human worker. The process evolved from engineers working on a stationary car, to a conveyor belt system where the car passed through multiple stations of more specialized engineers. Starting in the 1960s, robotic equipment was introduced to the process, and today most cars are produced largely with automated machinery.[4]

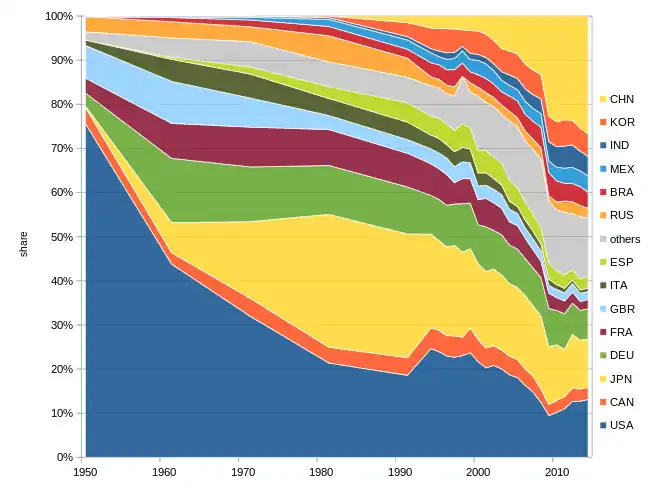

For many decades, the United States led the world in total automobile production. In 1929, before the Great Depression, the world had 32,028,500 automobiles in use, and the U.S. automobile industry produced over 90% of them. At that time, the U.S. had one car per 4.87 persons.[5] After 1945, the U.S. produced about 75 percent of world's auto production. In 1980, the U.S. was overtaken by Japan and then became a world leader again in 1994. In 2006, Japan narrowly passed the U.S. in production and held this rank until 2009, when China took the top spot with 13.8 million units. With 19.3 million units manufactured in 2012, China almost doubled the U.S. production of 10.3 million units, while Japan was in third place with 9.9 million units.[6] From 1970 (140 models) over 1998 (260 models) to 2012 (684 models), the number of automobile models in the U.S. has grown exponentially.[7]

Safety

Safety is a state that implies being protected from any risk, danger, damage, or cause of injury. In the automotive industry, safety means that users, operators, or manufacturers do not face any risk or danger coming from the motor vehicle or its spare parts. Safety for the automobiles themselves implies that there is no risk of damage.

Safety in the automotive industry is particularly important and therefore highly regulated. Automobiles and other motor vehicles have to comply with a certain number of regulations, whether local or international, in order to be accepted on the market. The standard ISO 26262, is considered one of the best practice frameworks for achieving automotive functional safety.[8]

In case of safety issues, danger, product defect, or faulty procedure during the manufacturing of the motor vehicle, the maker can request to return either a batch or the entire production run. This procedure is called product recall. Product recalls happen in every industry and can be production-related or stem from raw materials.

Product and operation tests and inspections at different stages of the value chain are made to avoid these product recalls by ensuring end-user security and safety and compliance with the automotive industry requirements. However, the automotive industry is still particularly concerned about product recalls, which cause considerable financial consequences.

Economy

In 2007, there were about 806 million cars and light trucks on the road, consuming over 980 billion litres (980,000,000 m3) of gasoline and diesel fuel yearly.[9] The automobile is a primary mode of transportation for many developed economies. The Detroit branch of Boston Consulting Group predicted that, by 2014, one-third of world demand would be in the four BRIC markets (Brazil, Russia, India, and China). Meanwhile, in developed countries, the automotive industry has slowed.[10] It is also expected that this trend will continue, especially as the younger generations of people (in highly urbanized countries) no longer want to own a car anymore, and prefer other modes of transport.[11] Other potentially powerful automotive markets are Iran and Indonesia.[12] Emerging automobile markets already buy more cars than established markets.

According to a J.D. Power study, emerging markets accounted for 51 percent of the global light-vehicle sales in 2010. The study, performed in 2010 expected this trend to accelerate.[13][14] However, more recent reports (2012) confirmed the opposite; namely that the automotive industry was slowing down even in BRIC countries.[10] In the United States, vehicle sales peaked in 2000, at 17.8 million units.[15]

In July 2021, the European Commission released its "Fit for 55" legislation package,[16] which contains important guidelines for the future of the automotive industry; all new cars on the European market must be zero-emission vehicles from 2035.[17]

The governments of 24 developed countries and a group of major car manufacturers including GM, Ford, Volvo, BYD Auto, Jaguar Land Rover and Mercedes-Benz committed to "work towards all sales of new cars and vans being zero emission globally by 2040, and by no later than 2035 in leading markets".[18][19] Major car manufacturing nations like the United States, Germany, China, Japan and South Korea, as well as Volkswagen, Toyota, Peugeot, Honda, Nissan and Hyundai, did not pledge.[20]

Environmental impacts

The global automotive industry is a major consumer of water. Some estimates surpass 180,000 L (39,000 imp gal) of water per car manufactured, depending on whether tyre production is included. Production processes that use a significant volume of water include surface treatment, painting, coating, washing, cooling, air-conditioning, and boilers, not counting component manufacturing. Paintshop operations consume especially large amounts of water because equipment running on water-based products must also be cleaned with water.[22]

In 2022, Tesla's Gigafactory Berlin-Brandenburg ran into legal challenges due to droughts and falling groundwater levels in the region. Brandenburg's Economy Minister Joerg Steinbach said that while water supply was sufficient during the first stage, more would be needed once Tesla expands the site. The factory would nearly double the water consumption in the Gruenheide area, with 1.4 million cubic meters being contracted from local authorities per year — enough for a city of around 40,000 people. Steinbach said that the authorities would like to drill for more water there and outsource any additional supply if necessary.[23]

World motor vehicle production

1960s: Post-war increase

1970s: Oil crisis and tighter safety and emission regulation

1990s: Production started in NICs.

2000s: Rise of China as a top producer

Automotive industry crisis of 2008–2010

1950s: United Kingdom, Germany, and France restarted production.

1960s: Japan started production and increased volume through the 1980s. United States, Japan, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom produced about 80% of motor vehicles through the 1980s.

1990s: South Korea became a volume producer. In 2004, Korea became No. 5 passing France.

2000s: China increased its production drastically, and became the world's largest-producing country in 2009.

2010s: India overtakes Korea, Canada, Spain to become 5th largest automobile producer.

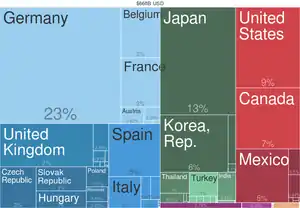

2013: The share of China (25.4%), India, Korea, Brazil, and Mexico rose to 43%, while the share of United States (12.7%), Japan, Germany, France, and United Kingdom fell to 34%.

2018: India overtakes Germany to become 4th largest automobile producer..png.webp)

By year

| Year | Production | Change | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 54,434,000 | — | [26] |

| 1998 | 52,987,000 | [26] | |

| 1999 | 56,258,892 | [27] | |

| 2000 | 58,374,162 | [28] | |

| 2001 | 56,304,925 | [29] | |

| 2002 | 58,994,318 | [30] | |

| 2003 | 60,663,225 | [31] | |

| 2004 | 64,496,220 | [32] | |

| 2005 | 66,482,439 | [33] | |

| 2006 | 69,222,975 | [34] | |

| 2007 | 73,266,061 | [35] | |

| 2008 | 70,520,493 | [36] | |

| 2009 | 61,791,868 | [37] | |

| 2010 | 77,857,705 | [38] | |

| 2011 | 79,989,155 | [39] | |

| 2012 | 84,141,209 | [40] | |

| 2013 | 87,300,115 | [41] | |

| 2014 | 89,747,430 | [42] | |

| 2015 | 90,086,346 | [43] | |

| 2016 | 94,976,569 | [44] | |

| 2017 | 97,302,534 | [45] | |

| 2018 | 95,634,593 | [46] | |

| 2019 | 91,786,861 | [47] | |

| 2020 | 77,621,582 | [48] | |

| 2021 | 80,145,988 | [49] | |

| 2022 | 85,016,728 | [50] | |

By country

The OICA counts over 50 countries that assemble, manufacture, or disseminate automobiles. Of those, only 15 countries (boldfaced in the list below) currently possess the capability to design original production automobiles from the ground up.[53][54]

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Australia (main page)

- Austria

- Azerbaijan

- Bangladesh (main page)

- Belarus (main page)

- Belgium

- Brazil (main page)

- Bulgaria (main page)

- Canada (main page)

- China (main page)

- Colombia

- Czech Republic (main page)

- Ecuador

- Egypt (main page)

- Finland

- France (main page)

- Ghana (main page)

- Germany (main page)

- Hungary (main page)

- India (main page)

- Indonesia (main page)

- Iran (main page)

- Italy (main page)

- Japan (main page)

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- Kenya (main page)

- Malaysia (main page)

- Mexico (main page)

- Morocco (main page)

- Netherlands

- Pakistan (main page)

- Philippines (main page)

- Poland (main page)

- Portugal

- Romania (main page)

- Russia (main page)

- Serbia (main page)

- Slovakia (main page)

- Slovenia

- South Africa (main page)

- South Korea (main page)

- Spain (main page)

- Sweden (main page)

- Syria

- Taiwan

- Thailand (main page)

- Tunisia

- Turkey (main page)

- Ukraine (main page)

- United Kingdom (main page)

- United States (main page)

- Uzbekistan (main page)

- Venezuela

- Vietnam (main page)

| Country | Motor vehicle production (units) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 27,020,615 | ||||||||

| United States | 10,060,339 | ||||||||

| Japan | 7,835,519 | ||||||||

| India | 5,456,857 | ||||||||

| South Korea | 3,757,049 | ||||||||

| Germany | 3,677,820 | ||||||||

| Mexico | 3,509,072 | ||||||||

| Brazil | 2,369,769 | ||||||||

| Spain | 2,219,462 | ||||||||

| Others | 2,030,138 | ||||||||

| Thailand | 1,883,515 | ||||||||

| Indonesia | 1,470,146 | ||||||||

| France | 1,383,173 | ||||||||

| Turkey | 1,352,648 | ||||||||

| Canada | 1,228,735 | ||||||||

| Czech Republic | 1,224,456 | ||||||||

| Slovakia | 1,000,000 | ||||||||

| United Kingdom | 876,614 | ||||||||

| Italy | 796,394 | ||||||||

| Malaysia | 702,275 | ||||||||

|

† = cars and LCV only[55] | |||||||||

By manufacturer

These were the 15 largest manufacturers by production volume in 2017, according to OICA.[51]

| Rank | Group | Country | Vehicles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toyota | Japan | 10,466,051 |

| 2 | Volkswagen Group | Germany | 10,382,334 |

| 3 | Hyundai | South Korea | 7,218,391 |

| 4 | General Motors | United States | 6,856,880 |

| 5 | Ford | United States | 6,386,818 |

| 6 | Nissan | Japan | 5,769,277 |

| 7 | Honda | Japan | 5,236,842 |

| 8 | Fiat Chrysler Automobilesa | Italy/United States | 4,600,847 |

| 9 | Renault | France | 4,153,589 |

| 10 | PSA Groupa | France | 3,649,742 |

| 11 | Suzuki | Japan | 3,302,336 |

| 12 | SAIC | China | 2,866,913 |

| 13 | Daimler | Germany | 2,549,142 |

| 14 | BMW | Germany | 2,505,741 |

| 15 | Geely | China | 1,950,382 |

Notable company relationships

Stake holding

It is common for automobile manufacturers to hold stakes in other automobile manufacturers. These ownerships can be explored under the detail for the individual companies.

Notable current relationships include:

- Daihatsu holds a 25% stake in Perodua.[56]

- Daimler holds a 10.0% stake in KAMAZ.

- Daimler holds an 89.29% stake in Mitsubishi Fuso Truck and Bus Corporation.

- Daimler holds a 3.1% in the Renault-Nissan Alliance, while Renault-Nissan Alliance holds a 3.1% share in Daimler AG.

- Daimler holds a 12% stake in BAIC Group, while BAIC Group holds 5% stake in Daimler.[57]

- Daimler holds an 85% stake in Master Motors.

- Dongfeng Motor holds a 12.23% stake and a 19.94% exercisable voting rights in PSA Groupe.

- FAW Group owns 49% of Haima Automobile.

- FCA holds a 10% stake in Ferrari.

- FCA holds a 67% stake in Fiat Automobili Srbija.

- FCA holds 37.8% of Tofaş with another 37.8% owned by Koç Holding.

- Fiat Automobili Srbija owns a 54% stake in Zastava Trucks.

- Fiat Industrial owns a 46% stake in Zastava Trucks.

- Fujian Motors Group holds a 15% stake in King Long. FMG, Beijing Automotive Group, China Motor, and Daimler has a joint venture called Fujian Benz. FMG, China Motor, and Mitsubishi Motors has a joint venture called Soueast, FMG holds a 50% stake, and both China Motor and Mitsubishi Motors holds an equal 25% stake.

- Geely Automobile holds a 23% stake in The London Taxi Company.

- Geely Automobile holds a 49.9% stake in PROTON Holdings and a 51% stake in Lotus Cars.[58]

- Geely Holding Group holds a 9.69% stake in Daimler AG.[59]

- Geely Holding Group holds an 8.3% stake and a 15.9% exercisable voting rights in Volvo.

- General Motors holds a 93% stake in GM India and SAIC Group holds a 7% stake.

- General Motors holds a 48.19% stake in GM Korea.

- General Motors holds a 20% stake in Industries Mécaniques Maghrébines.

- Isuzu owns 10% of Industries Mécaniques Maghrébines.

- Marcopolo owns 19% of New Flyer Industries.

- Mitsubishi Group holds 20% of Mitsubishi Motors.

- Nissan owns 34% of Mitsubishi Motors since October 2016,[60] thus having the right to nominate the chairman of Mitsubishi Motors' board and a third of its directors.

- Nissan owns 43% of Nissan Shatai.

- Porsche Automobil Holding SE has a 50.74% voting stake in Volkswagen Group. The Porsche automotive business is fully owned by the Volkswagen Group.

- Renault and Nissan Motors have an alliance (Renault-Nissan Alliance) involving two global companies linked by cross-shareholding, with Renault holding 43.4% of Nissan shares, and Nissan holding 15% of (non-voting) Renault shares.

- Renault holds a 25% stake in AvtoVAZ

- Renault holds an 80.1% stake in Renault Samsung.

- SAIPA holds a 51% stake in Pars Khodro.

- Tata Motors holds a 100% stake in Jaguar Land Rover.

- Toyota holds a 100% stake in Daihatsu.

- Toyota holds a 100% stake in Hino.

- Toyota holds a 4.6% stake in Isuzu.

- Toyota holds a 5.05% stake in Mazda, while Mazda holds 0.25% stake in Toyota.[61]

- Toyota holds a 16.7% stake in Subaru Corporation, parent company of Subaru.

- Toyota holds a 4.94% stake in Suzuki, while Suzuki holds 0.2% stake in Toyota.[62]

- Volkswagen Group holds a 99.55% stake in the Audi Group.

- Volkswagen Group holds a 37.73% stake in Scania (68.6% voting rights), a 53.7% stake in MAN SE (55.9% voting rights). Volkswagen is integrating Scania, MAN, and its own truck division into one division.

- Paccar has a 19% stake in Tatra.

- ZAP holds a 51% stake in Zhejiang Jonway.

China joint venture

- Beijing Automotive Group has a joint venture with Daimler called Beijing Benz, both companies hold a 50-50% stake. both companies also have a joint venture called Beijing Foton Daimler Automobile.

- Beijing Automotive Group also has a joint venture with Hyundai called Beijing Hyundai, both companies hold a 50-50% stake.

- BMW and Brilliance have a joint venture called BMW Brilliance. BMW owns a 50% stake, Brilliance owns a 40.5% stake, and the Shenyang municipal government owns a 9.5% stake.

- Changan Automobile has a joint venture with Groupe PSA (Changan PSA), and both hold a 50-50% stake.

- Changan Automobile has a joint venture with Suzuki (Changan Suzuki), and both hold a 50-50% stake.

- Changan Automobile has a 50-50% joint venture with Mazda (Changan Mazda).

- Changan Automobile and Ford have a 50-50% joint venture called Changan Ford.

- Changan Automobile and JMCG have a joint venture called Jiangling Motor Holding.

- Chery has a joint venture with Jaguar Land Rover called Chery Jaguar Land Rover, both companies hold a 50-50% stake.[63]

- Chery and Israel Corporation have a joint venture called Qoros, and both companies hold a 50-50% stake.

- Dongfeng Motor and Nissan have a 50-50% joint venture called Dongfeng Motor Company.

- Daimler AG and BYD Auto have a joint venture called Denza, both companies hold a 50-50% stake.

- Daimler AG and Geely Holding Group have a joint venture called smart Automobile, both companies hold a 50-50% stake.[64]

- Dongfeng Motor and PSA Group have a 50-50% joint venture called Dongfeng Peugeot-Citroën.

- Dongfeng Motor has a 50-50% joint venture with Honda called Dongfeng Honda.

- Dongfeng Motor has a joint venture with AB Volvo called Dongfeng Nissan-Diesel.

- Dongfeng Motor has a 50-50% joint venture with Renault named Dongfeng Renault in Wuhan, which was founded in the end of 2013

- FAW Group and General Motors has a 50-50 joint venture called FAW-GM.

- FAW Group has a 50-50 joint venture with Volkswagen Group called FAW-Volkswagen.

- FAW Group has a 50-50 joint venture with Toyota called Sichuan FAW Toyota Motor and both companies also have another joint venture called Ranz.

- General Motors and SAIC Motor, both have two joint ventures in SAIC-GM and SAIC-GM-Wuling.

- Navistar International and JAC has a joint venture called Anhui Jianghuai Navistar.

Outside China

- Ford and Navistar International have a 50-50 joint venture called Blue Diamond Truck.

- Ford and Sollers JSC have a 50-50 joint venture called Ford Sollers.

- Ford and Koç Holding have a 50-50 joint venture called Ford Otosan.

- Ford and Lio Ho Group have a joint venture called Ford Lio Ho, Ford owns 70% and Lio Ho Group owns 30%.

- General Motors and UzAvtosanoat have a joint venture called GM Uzbekistan, UzAvtosanoat owns 75% and General Motors owns 25%.

- General Motors, AvtoVAZ, and EBRD have a joint venture called GM-AvtoVAZ, Both GM and AvtoVAZ owns 41.61% and EBRD owns 16.76%.

- Hyundai Motor Company and Kibar Holding has a joint venture called Hyundai Assan Otomotiv, Hyundai owns 70% and Kibar Holding owns 30%.

- Isuzu and Anadolu Group have a 50-50% joint venture called Anadolu Isuzu.

- Isuzu and General Motors has a 50-50% joint venture called Isuzu Truck South Africa.

- Isuzu, Sollers JSC, and Imperial Sojitz have a joint venture called Sollers-Isuzu, Sollers JSC owns 66%, Isuzu owns 29%, and Imperial Sojitz owns 5%.

- Mahindra & Mahindra and Navistar International have a joint venture called Mahindra Trucks and Buses Limited. Mahindra & Mahindra owns 51% and Navistar International owns 49%.

- MAN SE and UzAvtosanoat have a joint venture called MAN Auto-Uzbekistan, UzAvtosanoat owns 51% and MAN SE owns 49%.

- PSA and Toyota have a 50-50% joint venture called Toyota Peugeot Citroën Automobile Czech.

- PSA and CK Birla Group (AVTEC) have a 50-50% joint venture called PSA AVTEC Powertrain Pvt. Ltd.

- Sollers JSC is involved in joint ventures with Ford (Ford Sollers ) and Mazda to produce cars.

- Tata Motors also formed a joint venture in India with Fiat and gained access to Fiat's diesel engine technology.

- Tata Motors and Marcopolo have a joint venture called Tata Marcopolo, where Tata owns 51% and Marcopolo owns 49%.

- Volvo Group and Eicher Motors have a 50-50% joint venture called VE Commercial Vehicles.

See also

- Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers

- Automotive industry by country

- Automotive industry crisis of 2008–2010

- Automotive industry in the United States

- Big Three (automobile manufacturers)

- Effects of the 2008–10 automotive industry crisis on the United States

- List of countries by motor vehicle production

- Motocycle

Notes

^a These figures were before the merger of both Fiat Chrysler Automobiles and Groupe PSA; the latter of which has merged into Stellantis as of January 2021.

References

- Automotive industry at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- "The 2021 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard" (PDF). European Commission. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Scientific and Technical Societies of the United States (Eighth ed.). Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. 1968. p. 164. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "The Timeline: Car manufacturing". The Timeline: Car Manufacturing. The Independent. 23 October 2011.

- "U.S. Makes Ninety Percent of World's Automobiles". Popular Science. Vol. 115, no. 5. November 1929. p. 84. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "2012 Production Statistics". OICA. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Aichner, T.; Coletti, P (2013). "Customers' online shopping preferences in mass customization". Journal of Direct, Data and Digital Marketing Practice. 15 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1057/dddmp.2013.34. S2CID 167801827.

- "ISO 26262-10:2012 Road vehicles -- Functional safety -- Part 10: Guideline on ISO 26262". International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Automobile Industry Introduction". Plunkett Research. 2008. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Khor, Martin. "Developing economies slowing down". twnside.org.sg. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "2014 Global Automotive Consumer Study : Exploring consumer preferences and mobility choices in Europe" (PDF). Deloittelcom. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- Eisenstein, Paul A. (21 January 2010). "Building BRIC's: 4 Markets Could Soon Dominate the Auto World". TheDetroitBureau.com.

- Bertel Schmitt (15 February 2011). "Auto Industry Sets New World Record In 2010. Will Do It Again In 2011". The Truth About Cars. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Global Automotive Outlook for 2011 Appears Positive as Mature Auto Markets Recover, Emerging Markets Continue to Expand". J.D. Power and Associates. 15 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- "U.S. vehicle sales peaked in 2000". The Cherry Creek News. 27 May 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "European Green Deal: Commission proposes transformation of EU economy and society to meet climate ambitions". European Commission. 14 July 2021.

- "Fit for 55: European Union to end sale of petrol and diesel models by 2035". Autovista24. 14 July 2021.

- "COP26: Deal to end car emissions by 2040 idles as motor giants refuse to sign". Financial Times. 8 November 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- "COP26: Every carmaker that pledged to stop selling fossil-fuel vehicles by 2040". CarExpert. 11 November 2021.

- "COP26: Germany fails to sign up to 2040 combustion engine phaseout". Deutsche Welle. 10 November 2021.

- "Highlights of the Automotive Trends Report". EPA.gov. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 12 December 2022. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023.

- Isaiah, David (6 October 2014). "Water, water, everywhere in vehicle manufacturing". Automotive World.

- Raymunt, Monica; Wilkes, William (22 February 2022). "Elon Musk Laughed at the Idea of Tesla Using Too Much Water. Now It's a Real Problem". bloomberg.com.

- "Table 1-23: World Motor Vehicle Production, Selected Countries (Thousands of vehicles)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- "Arno A. Evers FAIR-PR". Hydrogenambassadors.com. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "1998 - 1997 world motor vehicle production by type and economic area" (PDF). oica.net. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "1999 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2000 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2001 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2002 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2003 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2004 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2005 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2006 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2007 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2008 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2009 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2010 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2011 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2012 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2013 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2014 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2015 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2016 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2017 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2018 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2019 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2020 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2021 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- "2022 Production Statistics". oica.net.

- OICA: World Ranking of Manufacturers

- "Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity". US: Harvard University. 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- Lynch, Jared; Hawthorne, Mark (17 October 2015). "Australia's car industry one year from closing its doors". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "World Motor Vehicle Production by Country and Type" (PDF). oica.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- "2022 Production Statistics". OICA. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- "Perusahaan Ootmobil Kedua" [Second Automobile Company]. Malaysia: Perodua. 17 January 2017. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017.

- Sun, Edward; Taylor, Yilei (23 July 2019). "China's BAIC buys 5% Daimler stake to cement alliance". Reuters. US. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "China's Geely to Acquire Stake in Malaysian Carmaker Proton". Bloomberg.com. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- "Mercedes and Geely joint ownership of Smart". Auto Express. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Nissan to take 34% stake in Mitsubishi Motors". BBC News. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Toyota buys stake in Mazda, joint US factory, EV development planned | CarAdvice

- "Toyota pulls Suzuki firmly into its orbit through stake deal". Reuters. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Corporate Introduction". Chery Jaguar Land Rover. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "Mercedes-Benz and Geely Holding have formally established its global joint venture "smart Automobile Co., Ltd." for the smart brand". media.daimler.com (Press release). Retrieved 5 December 2020.

Further reading

- Ajitha, P. V., and Ankita Nagra. "An Overview of Artificial Intelligence in Automobile Industry–A Case Study on Tesla Cars." Solid State Technology 64.2 (2021): 503–512. online

- Banerjee, Preeta M., and Micaela Preskill. "The role of government in shifting firm innovation focus in the automobile industry" in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Sustainability (Routledge, 2017) pp. 108–129.

- Bohnsack, René, et al. "Driving the electric bandwagon: The dynamics of incumbents' sustainable innovation." Business Strategy and the Environment 29.2 (2020): 727–743 online.

- Bungsche, Holger. "Regional economic integration and the automobile industry: automobile policies, division of labour, production network formation and market development in the EU and ASEAN." International Journal of Automotive Technology and Management 18.4 (2018): 345–370.

- Chen, Yuan, C-Y. Cynthia Lin Lawell, and Yunshi Wang. "The Chinese automobile industry and government policy." Research in Transportation Economics 84 (2020): 100849. online

- Clark, Kim B., et al. "Product development in the world auto industry." Brookings Papers on economic activity 1987.3 (1987): 729–781. online

- Guzik, Robert, Bolesław Domański, and Krzysztof Gwosdz. "Automotive industry dynamics in Central Europe." in New Frontiers of the Automobile Industry (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020) pp. 377–397.

- Imran, Muhammad, and Jawad Abbas. "The role of strategic orientation in export performance of China automobile industry." in Handbook of Research on Managerial Practices and Disruptive Innovation in Asia (2020): 249–263.

- Jetin, Bruno. "Who will control the electric vehicle market?" International Journal of Automotive Technology and Management 20.2 (2020): 156–177. online

- Kawahara, Akira. The origin of competitive strength: fifty years of the auto industry in Japan and the US (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

- Kuboniwa, Masaaki. "Present and future problems of developments of the Russian auto-industry." RRC Working Paper Series 15 (2009): 1–12. online

- Lee, Euna, and Jai S. Mah. "Industrial policy and the development of the electric vehicles industry: The case of Korea." Journal of technology management & innovation 15.4 (2020): 71–80. online

- Link, Stefan J. Forging Global Fordism: Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and the Contest over the Industrial Order (2020) excerpt; influential overview

- Liu, Shiyong. "Competition and Valuation: A Case Study of Tesla Motors." IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science . Vol. 692. No. 2. (IOP Publishing, 2021) online

- Miglani, Smita. "The growth of the Indian automobile industry: Analysis of the roles of government policy and other enabling factors." in Innovation, economic development, and intellectual property in India and China (Springer, Singapore, 2019) pp. 439–463.

- Qin, Yujie, Yuqing Xiao, and Jiawei Yuan. "The Comprehensive Competitiveness of Tesla Based on Financial Analysis: A Case Study." in 2021 International Conference on Financial Management and Economic Transition (FMET 2021). (Atlantis Press, 2021). online

- Rawlinson, Michael, and Peter Wells. The new European automobile industry (Springer, 2016).

- Rubenstein, James M. The changing US auto industry: a geographical analysis (Routledge, 2002).

- Seo, Dae-Sung. "EV Energy Convergence Plan for Reshaping the European Automobile Industry According to the Green Deal Policy." Journal of Convergence for Information Technology 11.6 (2021): 40–48. online

- Shigeta, Naoya, and Seyed Ehsan Hosseini. "Sustainable Development of the Automobile Industry in the United States, Europe, and Japan with Special Focus on the Vehicles' Power Sources." Energies 14.1 (2021): 78+ online

- Ueno, Hiroya, and Hiromichi Muto. "The automobile industry of Japan." on Industry and Business in Japan (Routledge, 2017) pp. 139–190.

- Verma, Shrey, Gaurav Dwivedi, and Puneet Verma. "Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in comparison to combustion engine vehicles: A review." Materials Today: Proceedings (2021) online.

- Vošta, M. I. L. A. N., and A. L. E. Š. Kocourek. "Competitiveness of the European automobile industry in the global context." Politics in Central Europe 13.1 (2017): 69–89. online

- Zhu, Xiaoxi, et al. "Promoting new energy vehicles consumption: The effect of implementing carbon regulation on automobile industry in China." Computers & Industrial Engineering 135 (2019): 211–226. online

External links

Media related to Automotive industry at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Automotive industry at Wikimedia Commons