Bemba people

The Bemba belong to a large group of Bantu peoples mainly in the Northern, Luapula, Muchinga, and the northern Central Province of Zambia. The Bemba entered modern-day Zambia before 1740 by crossing the Luapula River from Kola. A few other ethnic groups in the Northern and Luapula regions of Zambia speak languages that are similar to Bemba but do not share a similar origin. The Bemba people are not indigenous to the Copperbelt Province, having reached there only in the 1930s due to employment opportunities in copper mining.

AbaBemba | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Bemba people | |

| Total population | |

| 4,100,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Zambia (Northern, Luapula and Tshopo Province (Democratic Republic of the Congo)) | |

| Languages | |

| Bemba language | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Traditional African religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lungu people and other Bantu peoples |

| Person | UmuBemba |

|---|---|

| People | AbaBemba, Awemba, BaWemba |

| Language | IchiBemba |

| Country | Kulubemba |

They lived in villages of 100 to 200 people and numbered 250,000 strong in 1963. The ethnicities known today as the Bemba have a ruling class called Abena Ng'andu. This clan traces its ancestry to Mbemba Nshinga who ruled Kongo 1509–1543. The traditional ruler of ethnic Bemba is Chitimukulu. The Bemba are one of the larger ethnic groups in Zambia, and their history is a significant historical phenomenon in the development of chieftainship in a large and culturally homogeneous region of Central Africa. The word Bemba originally meant a great expanse like the sea.

A sharp distinction should be made between Bemba-speaking peoples and ethnic Bemba people. There are 18 Bemba clans. These clans put a halt to the northward march of the Nguni and Sotho-Tswana descended Ngoni people, through Chief Chileshe Chitapankwa Muluba.

Bemba history is more aligned with the tribes of East Africa than the other tribes of Zambia. The fact that the Bemba is said to have come from Kola was misinterpreted by the Europeans to mean Angola. Oral Bemba folklore states that the Bemba originated from a woman who fell from heaven called Mumbi Mukasa, who had long ears. The Kikuyu of Kenya have the same folklore and similar traditions, including the way traditional huts were built. The Bemba have a rich vocabulary, including deserts and camels, which is certainly not something they would have known about if they were from Angola.

History (15th century to present)

Pre-1808

AbaBemba (the Bemba people) of Zambia in Central Africa are Bantus. The historiography of AbaBemba begins in the 15th century, with the 1484-1485 Portuguese expedition under Diego Cam (also known as Diogo Cão), when Europeans first made contact with the Kingdom of Kongo at the mouth of the Congo River.

Currently, there is no textus receptus of Bemba history; so, much of what is known about AbaBemba, especially about their early years, is a reasoned synthesis of scattered bits of history. Such history includes Bemba oral traditions,[2] historical texts on early imperialist and colonialist ventures and post-Berlin Conference European undertakings in the region,[3] inferences from historiographical mentions of well-known Bemba individuals [4] tie-ups with historical writings on other Central African kingdoms[5] and Bemba-focussed historiographical endeavors of the past century.[6]

Around 1484, Diego Cam came across the Congo River on the Atlantic Central African coast.[7] He explored the river. He came into contact with the Bantu Kongo Kingdom, which covered a vast area in many parts of the present-day countries of Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Congo-Brazzaville. The ruling monarch of the Kongo at that time was Nzinga a Nkuwu. [8] Locally, the monarchical title was Mani Kongo or Mwene Kongo, which translated as ‘the owner of the Kongo Kingdom’. Nzinga (known by AbaBemba as Nshinga) was Mwene Kongo VII. ‘Nkuwu’, with the grammatical prefix ‘a’, is a patronymic: Mwene Kongo Nzinga was a son of Nkuwu.

Primarily through the efforts of Catholic missionaries, the Portugal greatly influenced the internal politics of the Kongo Kingdom: Mwene Kongo VII Nzinga a Nkuwu was baptized in 1491 as João I (John I), the name of a Portuguese king (Gondola, 2002; Tanguy, 1948). Mwene Kongo Nzinga died in 1506[1] and was succeeded by his son Mvemba a Nzinga (Mvemba son of Nzinga). Mwene Kongo VIII Mvemba (also known as Muhemba, Mbemba, or Mubemba) also underwent Christian baptism and received a Portuguese regal name as his baptismal name: Alfonso I (Reid, 2012).

Shortly after the 1543 death of Mwene Kongo VIII Mvemba, a Nzinga (Alfonso Mubemba), early progenitors of AbaBemba rebelled against the Kongo Kingdom, which was becoming heavily influenced and dominated by the Portuguese, mainly through Christian conversion, slavery, trade, and European education. These rebels broke away from the Kongo Kingdom, migrated eastwards from their settlements in Kola, and became an integral part of the Luba Kingdom in the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo (Tanguy, 1948).

A 17th-century anti-Portuguese rebellion in the Luba Kingdom led to another eastward movement of the breakaway group that would later be known as AbaBemba. From the Luba Kingdom, the rebels were led by two of Luba King Mukulumpe’s sons: Nkole and Chiti (Mushindo, 1977; Tanguy, 1948). The mother of Nkole and Chiti was Mumbi Lyulu Mukasa of the Bena-Ng’andu clan. Since then, Bena-Ng’andu has become the royal clan of AbaBemba. A crocodile (ing’wena in modern Bemba; ing’andu in old Bemba) is the totemic object of the clan. Today, in the highly protected royal archives (babenye) at the palace of the Chitimukulu, are four Christian statues obtained 600 years ago from early Catholic missionaries in the Kongo Kingdom. Mwene Kongo VIII Mvemba a Mzinga (Alfonso Mubemba), is regarded as the ur-ancestor of AbaBemba. The onomatopoetic similarities between -vemba (in Mvemba) and –bemba (in AbaBemba) as well as the existence of the Christian statues in the royal archives (banenye) historically connect AbaBemba to the Kongo Kingdom.

The proto-AbaBemba migrated from the Luba Kingdom, crossed the Luapula River, and settled first at Isandulula (below Lake Mweru), then at Keleka near Lake Bangweulu, Chulung’oma, and then Kashi-ka-Lwena. Afterward, they then crossed the Chambeshi River at Safwa Rapids and settled at Chitabata, Chibambo, Ipunga, Mungu, and Mulambalala. Then they crossed the Chambeshi River again, moving back west to Chikulu. A royal omen at the Milando River supposedly compelled AbaBemba to settle and cease their migrations (Mushindo, 1977; Tanguy, 1948; Tweedie, 1966). This settlement was named Ng’wena and became the first capital of UluBemba – the Bemba Kingdom. The Bemba-Ngoni wars of the 19th century were fought in the region around Ng’wena.

From the time AbaBemba established themselves as a distinct grouping to the time of the 21st Chitimukulu, the Bemba were said to have been ruled by a single Paramount Chief or King (Roberts, 1970, 1973; Tanguy, 1948). However, during the reign of the 22nd Chitimukulu at the end of the 18th century, AbaBemba became markedly more expansionist. Chitimukulu Mukuka wa Malekano started pushing AbaLungu (the Lungu people) out of the present-day Kasama area. When he had forced AbaLungu to move west and settle on the western side of the Luombe River, the geographical area of the Bemba Kingdom had grown to such an extent that it was not practical to manage it from UluBemba. So, Chitimukulu Mukuka wa Malekano gave the newly acquired Ituna area to his young brother Chitundu as a separate Mwamba Kingdom, a tributary state of the Bemba Kingdom (Mushindo, 1977; Tanguy, 1948). Chitundu became Mwine Tuna, Mwamba I.

Post-1808

Under the 23rd Chitimukulu Chilyamafwa AbaBemba, expansion continued in the years leading up to 1808. Chitimukulu pushed AbaMambwe (Mambwe people) north, creating the area that would be called Mpanda. At the same time, Chitimukulu Chilyamafwa’s young brother, Mubanga Kashampupo, who had ascended to the Mwamba throne as Mwine Tuna Mwamba II, continued pushing AbaLungu west and south, creating the Kalundu area. Chitimukulu Chilyamafwa created a vassal Mpanda kingdom over which his son Nondo-mpya would reign as Makasa I; Mwamba Kashampupo created a vassal Kalundu kingdom over which his son would rule as Munkonge I (Tanguy, 1948). Future Bemba kings continued the conquests, with both the 25th Chitimukulu, Chileshe Chepela (1810-1860), and the 27th Chitimukulu, Mutale Chitapankwa (1866-1887) bringing nearby tribes under their rule.

By the time the first significant European presence began to make itself known in Zambia at the end of the 1800s, AbaBemba had pushed out many earlier immigrants to the Tanganyika plateau: including the Tabwa, Bisa, Lungu, and Mambwe. UluBemba extended to varying degrees as far north as Lake Tanganyika, south-west to the swamps of Lake Bangweulu, eastwards to the Muchinga Escarpment and Luangwa Valley, and as far as Lake Mweru in the west. AbaBemba was subdivided into over fifteen chieftainships under Chitimukulu’s various brothers, sons, and nephews. Richards (1939) observes that the political influence of the Chitimukulu covered much of the area marked out by the four great lakes (Mweru, Bangweulu, Tanganyika, and Nyasa) and extended south into the Lala country in present-day Central.

Despite the advent of colonial rule and later independence, many Bemba political institutions remain similar to their old forms. The Chitimukulu is the Mwine Lubemba (owner of the Bemba kingdom) and Paramount chief; UluBemba is divided into semi-autonomous chieftainship under the reign of the Chitimukulu’s brothers, sons, and nephews. Nkula and Mwamba are the senior brothers of the Chitimukulu and are usually the heirs to the Chitimukulu's throne; Nkole Mfumu and Mpepo are the junior brothers of the Chitimukulu. Nkole Mfumu usually comes to the Mwamba throne, while Mpepo usually comes to the Nkole Mfumu throne. Occasionally, Mpepo and Nkole Mfumu have gone directly to the Chitimukulu throne. Of the sons of Chitimukulu, Makasa is the senior.

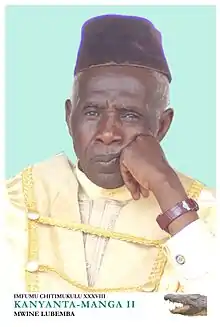

Since the establishment of the Protectorate in the early 20th century in the reign of the 30th Chitimukulu, Mutale Chikwanda (1911-1916), the Chitimukulu throne is now more cultural and ceremonial than executive and administrative. However, this has not entirely removed the Paramount Chief's political importance. Chitimukulu, Chitimukulu Kanyanta-manga II, is the 38th on the Chitimukulu throne. He came to the throne in August 2013 and was crowned on 31 July 2015. In 2016, Chitimukulu Kanyanta-manga II wrote an article entitled: The Illusive Role of the Chitimukulu reflecting on the institution he had assumed. This article set out the leadership roles the 38th Chitimukulu sought to assume.[9] Soon afterward, the Paramount Chief put out his socio-economic development agenda for the Bemba kingdom, envisioning the establishment of an UluBemba Academy and resolving to harness tourism and industrial potential for his people. All developmental and investment programs are to be coordinated by the already-established UluBemba Investment Centre, which Chitimukulu Kanyanta-manga II was responsible for setting up.

Language

The Bemba language (Ichibemba) is most closely related to the Bantu languages Kiswahili in East Africa, Kaonde in Zambia and the DRC, Luba in the DRC, Nsenga, and Nyanja/Chewa in Zambia and Malawi. In Zambia, Chibemba is mainly spoken in the Northern, Luapula, and Copperbelt Provinces, unlike in Northern province and Luapula. Bemba is not an indigenous language in the Copper Belt; what is in the Copper Belt is the Lenje, Lamba, and Sala the Bantu Botatwe languages.

Culture

Many Bemba are slash-and-burn agriculturists, with manioc and finger millet being their main crops. However, many Bemba also raise goats, sheep, and other livestock. Some Bemba are also employed in the mining industry.[10]

Traditional Bemba society is matrilineal where close bonds between women or a mother and daughter are considered essential.[10]

Quotes from studies of AbaBemba

Richards (1939, pp. 29–30) observes that AbaBemba

“…are obsessed with problems of status and constantly on the look-out for their dignity, as is perhaps natural in a society in which so much depends on rank. All their human relations are dominated by rules of respect to age and position… Probably this universal acceptance of the rights of rank makes the Bemba appear so submissive and almost servile to the European… Arrogant towards other tribes, and touchy towards their fellows, they seem to endure in silence any treatment from a chief (sic, should read ‘monarch’) or a European.

To my mind, their most attractive characteristics are quick sympathy and adaptability in human relationships, an elaborate courtesy and sense of etiquette, and great polish of speech. A day spent at the Paramount’s (sic, should read ‘King’) court is apt to make a European observer's manners seem crude and boorish by contrast.” (pp. 139-140)

Mukuka (2013, pp. 139–140), observes that

"With the introduction of the English polity in the (Northern Rhodesia) colony, the long-established Bemba civilization and its intrinsic psychological realities were disrupted. For many abaBemba, the arbitrary amalgamation of 70-plus ethnic groups meant 1) a new identity, incomprehensible and groundless; 2) fears of loss of what they had known (politically, socially and economically) about managing their lives; and, 3) new centers of power (political, social, and cultural) that they had to learn to navigate. Insaka and ifibwanse, the long-established centers for educating Bemba boys and girls, respectively, lost their power to Western schools that promised successful learners the social status next to that of the ‘white’ colonisers. Bemba cultural practices and ideals were harshly judged by both colonisers and Christian missionaries. Consequently, abaBemba asked: who are we in Northern Rhodesia? What is our place in this new amalgam? How do we fit in? Taking advantage of the written text, questions of who we are, where we are, and how we fit in found expression in Bemba literature; particularly the over twenty documented Bemba factual novels..."

See also

References

Notes

- For Tanguy (1948), the year of death of Mwene Kongo VII Mzinga is 1507; for Gondola (2002), it is 1506.[1]

Citations

- "Bemba | Joshua Project". Joshua Project. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Mushindo, 1977; Tanguy, 1948

- Bandinel, 1842; Richards, 1939; Roberts, 1970; Tweedie, 1966

- Bandinel, 1842; Gondola, 2002; Reid, 2012

- African Elders & Labrecque, 1949; Gondola, 2002; Reid, 2012

- Mushindo, 1977; Roberts, 1970; Roberts, 1973; Tanguy, 1948)

- Bandinel, 1842

- Gondola, 2002

- "The illusive role of the Chitimukulu as the chief executive of the Bemba people and tribe," Lusaka Times published 20 May 2016.

- Winston, Robert, ed. (2004). Human: The Definitive Visual Guide. New York: Dorling Kindersley. p. 423. ISBN 0-7566-0520-2.

Bibliography

- Bandinel, J. (1842). Some account of the trade in slaves from Africa as connected with Europe and America: From the introduction of the trade into modern Europe, down to the present time. London: Longman, Brown, & Co.

- Gondola, D. (2002). The History of Congo: The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations. London: Greenwood Press.

- Mukuka, R. (2013). Ubuntu in S. M. Kapwepwe’s Shalapo Canicandala: Insights for Afrocentric psychology. Journal of Black Studies, 44(2), 137-157.

- Mushindo, P. M. B. (1977). A Short history of the Bemba: As narrated by a Bemba. Lusaka: Neczam.

- Reid, R. J. (2012). A history of modern Africa: 1800 to the present (2nd ed.). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Richards, A. I. (1939). Land, labour, and diet in Northern Rhodesia: An economic study of the Bemba tribe. London: Oxford University Press.

- Roberts, A. (1970). Chronology of the Bemba (N.E. Zambia). Journal of African History, 11(2), 221-240.

- Roberts, A. D. (1973). A history of the Bemba: Political growth and change in north-eastern Zambia before 1900. London: Longman.

- Tanguy, F. (1948). Imilandu ya Babemba [Bemba history]. London: Oxford University Press.

- African Elders & Labrecque, E. (1949). History of Bena-Ng’oma (Ba Chungu wa Mukulu). London, Macmillan & Co. Ltd.

Further reading

- Posner, Daniel N. (2003). "The Colonial Origins of Ethnic Cleavages: The Case of Linguistic Divisions in Zambia". Comparative Politics. 35 (2): 127–146.