Bagamoyo Historic Town

Bagamoyo Historic Town or Bagamoyo Stone Town (Mji wa Kale wa Bagamoyo au Mji Mkongwe wa Bagamoyo, In Swahili), is the historic section of Bagamoyo town in Bagamoyo District of Pwani Region. Due to its historic significance spanning centuries and empires, Old Bagamoyo is a National Historic Site of Tanzania. The settlement was first inhabited in the 8th century as a Zaramo village and then a Swahili stone settlement, satellite to Kaole.[2] One of the most significant trading hubs on the coast of East Africa, Bagamoyo served as the last halt for ivory caravans making their way on foot from Lake Tanganyika to Zanzibar.

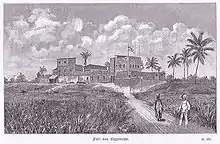

Bagamoyo Historic Town in Bagamoyo c. 1906 | |

Shown within Tanzania | |

| Location | Pwani Region, Bagamoyo District, Bagamoyo |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 6°26′40″S 38°54′10″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Material | Coral rag |

| Founded | 8th century |

| Cultures | Swahili |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Endangered |

| Ownership | Tanzanian Government |

| Management | Antiquities Division, Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism [1] |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Swahili, Omani and German |

| Official name | Bagamoyo Historic Town |

| Type | Cultural |

Etymology

Bagamoyo's name means "take a load off your heart" in Kiswahili. The phrase is meant to make you feel at ease by removing your burden. This is in reference to Bagamoyo's 19th century reputation as a town of porters. The historic hamlet served as the final stop for thousands of porters who carried, on average, 70-pound burdens held across their shoulders, mostly ivory tusks, along the caravan route. Bagamoyo beckoned as a location of rest and enjoyment, trying to reward the men after a taxing voyage after trekking for months across hazardous terrain.[3][4]

August Leue, a district officer to Bagamoyo in the late nineteenth century, interpreted a song chanted by the Nyamwezi porters as they marched into the town as a means of supporting the later interpretation of the town's name. "Be happy, my soul, surrender all worry/soon the place of your desires will be reached/the town of palms - Bagamoyo," sings the hymn, praising the town as a destination that upcountry Africans desired to visit. "Be still my heart, all worries are gone/the call to rest thunders out, and with jubilation/we reach Bagamoyo," the poem concludes, is similar in tone. The second meaning of the town's name—to be at peace—is evoked by both lines. There were other settlements in Tanzania's interior with the name Bagamoyo, according to Walter Brown, a pre-colonial historian of the town.[5][6]

History

In the 15th century, early Bagamoyo was a little satellite town of Kaole, a few kilometres south, and a originally a Zaramo settlement. The Shomvi, whose ancestors arrived in the area in the middle of the eighteenth century from a location further north along the shoreline at Malindi, established the surviving Bagamoyo Historic Town, according to oral tradition. The settlement began as a fishing and farming community that traded small amounts of local goods, slaves, copal, and ivory for Indian fabric industry as early as the 1810s. In the early 1800s, the Omanis turned adjoining Zanzibar into the main commerce hub of the western Indian Ocean, and Bagamoyo's fortunes improved at the same time. Bagamoyo dominated the trade on the Mrima, the coastal landmass of central East Africa, until the later half of the nineteenth century. Each year, thousands of African porters arrived in Bagamoyo with cattle or loads of other goods from as far away as the Great Lakes region, including ivory, gum copal, rubber, and many other goods.[7]

The porters brought these with them back to the interior to sell or keep for their own use after exchanging them for fabric, guns, copper wire, and other commodities in town. The local economy would benefit further if the porters stayed in Bagamoyo for up to three or four months. Bagamoyo is described by Tanzanian and Bagamoyo historians as having a fairly diversified population without any strong ethnic groups. Being a commercial hub, Bagamoyo historically served as a home for traders, financiers, farmers, slaves, porters, fisherman, sailors, and artisans. [8]

Bagamoyo and the slave trade

Bagamoyo, a little settlement before 1850, could not have provided the Indian Ocean commerce system with large numbers of enslaved Africans; Kilwa, considerably farther south along the Tanzanian coastline, was known for doing so. Southeast Africa developed into the heart of the world's slave trade during the 1780s and 1870s, serving both the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean markets. Four factors contributed to this phenomenon: first, the growth of French plantations in the Mascarene Islands; second, Brazilian planters' demand for new slave sources in the wake of the expansion of British anti-slavery patrols in the Atlantic Ocean beginning in 1807; third, the expansion of the clove plantation economy in Zanzibar; and fourth, the cultivation of sugarcane and rice on the mainland.[9]

Kilwa was still recognised as the "principal slave-exporting port of the East African mainland" even after 1850, when Bagamoyo started to rise to economic dominance. This status persisted until 1873, when the British started enforcing the abolition of the foreign slave trade from the eastern coast. The main objective of British anti-slavery naval patrols was Kilwa. Slave their routes northward through land as a result, using the numerous creeks and inlets for shipping to avoid being discovered by the British navy. This extraordinary slave trade through Bagamoyo eventually became just one of numerous sales and exports.17 That grew the further north they were marched, from $12–15 in Dar es Salaam to $25–40 in Pangani and $60–80 in Barawa, according to the British General Consul to Zanzibar. However, British observers in Zanzibar never stated that Bagamoyo was worthy of slavery. After the slave trade was outlawed, Pangani, to the north of Bagamoyo, became the primary slave market along the coast.[10][11]

According to a survey done by the German government in the late 1890s, Bagamoyo had one of the smallest populations of coastal towns, with roughly 15% of its inhabitants being slaves. Even the capital of German East Africa, Dar es Salaam, had twice as many slaves as Bagamoyo in 1891. Bagamoyo had frequent slave smuggling in the late nineteenth century when parti caravan porters were there.Even as late as 1900, the Germans were unable to prove that slavenapping had taken place; younger, less experienced Nyamwezi were the victims. Despite this, the archives have no information regarding the distance from Bagamoyo before or after 1873. This is likewise true of the European explorers that entered or exited Bagamoyo's interior in the late nineteenth century. Although these guys saw slave caravans and the destruction in the interior, a slave market is not mentioned in their journey accounts. Henry Stanley, who made three trips there between 1871, described the port as a hub of the slave trade in his well-known travelogues.[12][13] Father Anton Horner, the mission's founder, stated that Kilwa and Zanzibar were the epicentres of the East African slave trade in 1869, about a year after the mission was founded, but he made no similar remarks about Bagamoyo. In fact, the majority of freed slaves who the missionaries converted and assisted in raising in Bagamoyo were either bought at the Zanzibar slave market or were liberated slaves given to them by the British anti-slavery naval partrol. The reality, however, has more to do with the town's ties to the thousands of porters - the Nyamwezi - who travelled to the coast each year from their homeland in the interior than slaves. There seems to be a current popular misconception that the French Catholic Mission's goal in Bagamoyo was to end the slave trade. As long-distance traders, these individuals were thought to be more likely to convert to Christianity than the coastal Muslims, which the missionaries hoped would help the religion grow into the East African interior.[14]

Despite historical records to the contrary, the Bagamoyo Catholic Museum of the Tanzanian Tourist Board has largely contributed to the development and perpetuation of the myth in Tanzania that Bagamoyo was an important port for the African slave trade.[15][16]

The site's main attractions

Several noteworthy nineteenth-century structures can be seen in Bagamoyo, including merchant residences and several places of worship. However, many of the town's architectural forms may be seen in Stone Town, Zanzibar, or Lamu, Kenya, which are also UNESCO World Heritage Sites, in considerably higher quality, variety, and number. The caravanserai, however, is one structure that genuinely sets Bagamoyo apart. This building serves as a memorial to the ivory trade, which made this town famous. Long before plastics were developed, the globe used ivory in a variety of products for consumption, including cutlery handles, airtight containers, combs, piano keys, billiard balls, buttons, and clasps, to mention a few. The ivory exports from Bagamoyo were closely monitored by Arab, Indian, European, and American businessmen, who competed with one another, the locals, and the African porters for ownership of the city's vast wealth. Several European explorers chose it as their departure point in the late nineteenth century due to its reputation as the city that served as the entry point into the interior of Africa along well-traveled caravan routes.[17]

The caravanserai has a sizable square courtyard that is surrounded by four long, adjacent wings that are rectangular and have rooms and storage areas. A two-story building that acted as both an observation tower and administrative offices is located in the middle of the courtyard. The site serves as the new local headquarters for the Tanzania Department of Antiquities. It was renovated with financial support from the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA).[18]

A sizable signage that was given by SIDA and the University of Dar es Salaam is located outside the building's front gates. The information on the signpost is problematic and false. Nowhere does it say that the building tourists are admiring was created in 1890 by a Danish planter working for the German East Africa Company. The Germans supported the institution of slavery, but they did not promote the slave trade in their colony. Therefore, it seems improbable that the current building housed as many as 50,000 slaves annually when under German control. 50,000 slaves are said to have arrived in Bagamoyo in the first half of the nineteenth century, according to the Bagamoyo Catholic Museum, but only 10,000 porters are said to have come to the city annually during that time. The statistics provided by the museum do not add up if we are to believe that slave and porter were interchangeable as suggested by the notice at the caravanserai.[19][20]

A tax assessment of the caravanserai from the German colonial-era records kept at the Tanzania National Archives demonstrates Rockel's point. The document gives a detailed description of the current caravanserai construction, which is flanked by ten long, rectangular shelters that were arranged in a clockwork pattern but are no longer there. Up to 5,000 porters could be housed in the compound collectively, each of whom had to pay a half-rupee lodging charge.The Germans wanted to govern and organise the huge, unruly porter encampments that were dispersed across the town, not to prohibit or regulate slaving operations. Instead, they were motivated by this desire to do so. Finally, research conducted in and around the caravanserai in 2001–2002 under the direction of Professor Felix Chami of the University of Dar es Salaam found no evidence that the building was connected to a slave market.[21][22]

.jpg.webp)

The caravanserai also serves as a powerful continuation for Bagamoyo's secondary function as a destination for leisure. While trade was the town's main source of income, the porters chose this location over all the other competing locations along the central East African coastline each year for recreation and enjoyment. Rifles would be shot as the porters approached Bagamoyo, and women would ululate and children would rush to welcome the upcountry as they arrived, according to European reports from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[23][24]

The Old Fort, the Customs House, and the Caravaserai are the three buildings marked out for harbouring numerous slaves. The Old Fort, which dates to the German occupation, housed the liwali, or the governor, to Zanzibar's business interests in Bagamoyo. It is the oldest remaining edifice in the port town. The rectangular, three-story structure was leased by an Indian businessman to the Liwali in 1874 and eventually served as the DOA's headquarters starting in 1888. The Old Fort operated as the town's jail and police station until the Germans constructed a new administrative boma (fort) in the middle of the 1890s. In the late 1950s, it also served as the first location of the Tanzanian Department of Antiquities. Today, it is a museum where visitors can find documents that outline the site's history.[25]

During the Coastal Uprising in 1888, the Germans significantly altered the Old Fort. They increased its size, raised its walls, built four bastions, and added windows. The "door of no return" that the Germans built there faced the water. The Customs House is the next noteworthy building. Once more, the area was huge and semi-enclosed, although in this instance it was centred between offices and living quarters. This building is unrelated to the earlier one because it was totally created by German architects in the middle of the nineteenth century, drawing inspiration from their native country. It was also not constructed by the former Omani customs house, eliminating the chance that slave selling took place there.[26]

See also

References

- "Antiquities Division". Retrieved 21 Jul 2022.

- "Bagamoyo Stone Town History". Retrieved 2023-09-24.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Brown, Walter Thaddeus. A pre-colonial history of Bagamoyo: Aspects of the growth of an East African coastal town. Boston University Graduate School, 1971.

- Brown, Walter Thaddeus. A pre-colonial history of Bagamoyo: Aspects of the growth of an East African coastal town. Boston University Graduate School, 1971.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Lello, Didas S., and Paulina C. Mwasanyila. "Local Community-Based Participation on Conservation of Heritage Buildings: Experiences from Bagamoyo Historical Town, Tanzania." Int. Res. J. Eng. Tech 5 (2018): 2212-2226.

- Fabian, Steven. “Curing the Cancer of the Colony: Bagamoyo, Dar Es Salaam, and Socioeconomic Struggle in German East Africa.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 40, no. 3, 2007, pp. 441–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034038. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Lello, Didas S., and Paulina C. Mwasanyila. "Local Community-Based Participation on Conservation of Heritage Buildings: Experiences from Bagamoyo Historical Town, Tanzania." Int. Res. J. Eng. Tech 5 (2018): 2212-2226.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. Making identity on the Swahili coast: Urban life, community, and belonging in Bagamoyo. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Fabian, Steven. “Curing the Cancer of the Colony: Bagamoyo, Dar Es Salaam, and Socioeconomic Struggle in German East Africa.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 40, no. 3, 2007, pp. 441–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40034038. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Lello, Didas S., and Paulina C. Mwasanyila. "Local Community-Based Participation on Conservation of Heritage Buildings: Experiences from Bagamoyo Historical Town, Tanzania." Int. Res. J. Eng. Tech 5 (2018): 2212-2226.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.

- Fabian, Steven. “East Africa’s Gorée: Slave Trade and Slave Tourism in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, vol. 47, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–114. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43860408. Accessed 24 Sept. 2023.