Bálint's syndrome

Bálint's syndrome is an uncommon and incompletely understood triad of severe neuropsychological impairments: inability to perceive the visual field as a whole (simultanagnosia), difficulty in fixating the eyes (oculomotor apraxia), and inability to move the hand to a specific object by using vision (optic ataxia).[1] It was named in 1909 for the Austro-Hungarian neurologist and psychiatrist Rezső Bálint who first identified it.[2][3][4]

| Bálint's syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Balint-Holmes syndrome, Optic ataxia-gaze apraxia-simultanagnosia syndrome |

| |

| Balint Syndrome | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Ophthalmology, Optometry |

Bálint's syndrome occurs most often with an acute onset as a consequence of two or more strokes at more or less the same place in each hemisphere. Therefore, it occurs rarely. The most frequent cause of complete Bálint's syndrome is said by some to be sudden and severe hypotension, resulting in bilateral borderzone infarction in the occipito-parietal region.[1] More rarely, cases of progressive Bálint's syndrome have been found in degenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease[5][6] or certain other traumatic brain injuries at the border of the parietal and the occipital lobes of the brain.

Lack of awareness of this syndrome may lead to a misdiagnosis and resulting inappropriate or inadequate treatment. Therefore, clinicians should be familiar with Bálint's syndrome and its various etiologies.[7]

Presentation

Bálint's syndrome symptoms can be quite debilitating since they impact visuospatial skills, visual scanning and attentional mechanisms.[8] Since it represents impairment of both visual and language functions, it is a significant disability that can affect the patient's safety—even in one's own home environment, and can render the person incapable of maintaining employment.[9] In many cases the complete trio of symptoms—inability to perceive the visual field as a whole (simultanagnosia), difficulty in fixating the eyes (oculomotor apraxia), and inability to move the hand to a specific object by using vision (optic ataxia)—may not be noticed until the patient is in rehabilitation. Therapists unfamiliar with Bálint's syndrome may misdiagnose a patient's inability to meet progress expectations in any of these symptom areas as simply indicating incapability of benefiting from further traditional therapy. The very nature of each Bálint symptom frustrates rehabilitation progress in each of the other symptoms. Much more research is needed to develop therapeutic protocols that address Bálint symptoms as a group since the disabilities are so intertwined.[10]

Simultanagnosia

Simultanagnosia is the inability to perceive simultaneous events or objects in one's visual field.[11] People with Bálint's syndrome perceive the world erratically, as a series of single objects rather than seeing the wholeness of a scene.[12]

This spatial disorder of visual attention—the ability to identify local elements of a scene, but not the global whole—has been referred to as a constriction of the individual's global gestalt window—their visual "window" of attention. People fixate their eyes to specific images in social scenes because they are informative to the meaning of the scene. Any forthcoming recovery in simultanagnosia may be related to somehow expanding the restricted attentional window that characterizes this disorder.[13]

Simultanagnosia is a profound visual deficit. It impairs the ability to perceive multiple items in a visual display, while preserving the ability to recognize single objects. One study suggests that simultanagnosia may result from an extreme form of competition between objects which makes it difficult for attention to be disengaged from an object once it has been selected.[14] Patients with simultanagnosia have a restricted spatial window of visual attention and cannot see more than one object at a time. They see their world in a patchy, spotty manner. Therefore, they pick out a single object, or even components of an individual object, without being able to see the global "big picture."

A study which directly tested the relationship between the restriction of the attentional window in simultanagnosia compared with the vision of healthy participants with normal limits of visual processing confirmed the limitations of difficulties of patients with simultanagnosia.[15]

There is considerable evidence that a person's cortex is essentially divided into two functional streams: an occipital-parietal-frontal pathway that processes "where" information and an occipital-temporal-frontal pathway that provides "what" information to the individual.[16]

Oculomotor apraxia

Bálint referred to this as "psychic paralysis of gaze"—the inability to voluntarily guide eye movements, changing to a new location of visual fixation. A major symptom of Oculomotor apraxia is that a person has no control over their eye movements, however, vertical eye movements are typically unaffected. For example, they often have difficulty moving their eyes in the desired direction. In other words, the saccades (rapid eye movements) are abnormal. Because of this, most patients with Oculomotor apraxia have to turn their heads in order to follow objects coming from their peripherals.[17]

Optic ataxia

Optic ataxia is the inability to guide the hand toward an object using visual information[18] where the inability cannot be explained by motor, somatosensory, visual field deficits or acuity deficits. Optic ataxia is seen in Bálint's syndrome where it is characterized by an impaired visual control of the direction of arm-reaching to a visual target, accompanied by defective hand orientation and grip formation.[19] It is considered a specific visuomotor disorder, independent of visual space misperception.

Optic ataxia is also known as misreaching or dysmetria (English: difficult to measure), secondary to visual perceptual deficits. A patient with Bálint's syndrome likely has defective hand movements under visual guidance, despite normal limb strength. The patient is unable to grab an object while looking at the object, due to a discoordination of eye and hand movement. It is especially true with their contralesional hand.

Dysmetria refers to a lack of coordination of movement, typified by the undershoot or overshoot of intended position with the hand, arm, leg, or eye. It is sometimes described as an inability to judge distance or scale.[18]

As Bálint states, optic ataxia impaired his patient's daily activities, since, 'while cutting a slice of meat...which he held with a fork in his left hand, ...would search for it outside the plate with the knife in his right hand', or '...while lighting a cigarette he often lit the middle and not the end'. Bálint pointed out the systematic nature of this disorder, which was evident in the patient's behaviour when searching in space. 'Thus, when asked to grasp a presented object with his right hand, he would miss it regularly, and would find it only when his hand knocked against it.[19]

The reaching ability of the patient is also altered. It takes them longer to reach toward an object. Their ability to grasp an object is also impaired. The patient's performance is even more severely deteriorated when vision of either the hand or the target is prevented.[20]

Cause

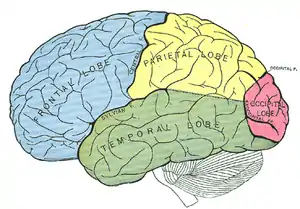

The visual difficulties in Bálint's syndrome are usually due to damage to the parieto-occipital lobes on both sides of the brain. The parietal lobe is the middle area of the top part of the brain and the occipital lobe is the back part of the brain. (It usually does not affect the temporal lobes)

Diagnosis

Lack of awareness of the syndrome may lead to misdiagnosis such as blindness, psychosis, or dementia.[1] Symptoms of Bálint's syndrome are most likely to be noticed first by optometrists or ophthalmologists during an eye check up, or therapists providing rehabilitation following brain lesions. However, due to the scarcity among practitioners of familiarity with the syndrome, the symptoms are often explained away incorrectly without being considered as a possibility and followed by medical confirmation of clinical and neuroradiological findings.[21] Any severe disturbance of space representation, spontaneously appearing following bilateral parietal damage, strongly suggests the presence of Bálint's syndrome and should be investigated as such.[22] One study reports that damage to the bilateral dorsal occipitoparietal regions appeared to be involved in Bálint's syndrome.[23]

Neuroanatomical evidence

Bálint's syndrome has been found in patients with bilateral damage to the posterior parietal cortex. The primary cause of the damage and the syndrome can originate from multiple strokes, Alzheimer's disease, intracranial tumors, or brain injury. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease have also been found to cause this kind of damage. This syndrome is caused by damage to the posterior superior watershed areas, also known as the parietal-occipital vascular border zone (Brodmann's areas 19 and 7).[24]

Manifestations

Some telltale signs suggesting Bálint's syndrome following bilateral brain insults may include:

- limitation to perceive only stimuli that is presented at 35 to 40 degrees to the right. They are able to move their eyes but cannot fixate on specific visual stimuli (optic apraxia).

- patient's field of attention is limited to one object at a time. making activities like reading difficult because each letter is perceived separately (simultanagnosia).

- figure/ground defects in which a patient can see either the background but not the object residing somewhere in the whole scene, or conversely can see the object but sees no background around it (simultanagnosia)

- a patient, while attempting to put one foot into a slipper by trying to insert the foot into a nonexistent slipper several inches from the real slipper, even as the patient focuses on the actual slipper (optic ataxia)

- a patient raising a fork or spoon containing food to a point on the patient's face above or below the mouth, and possibly finding the mouth by trial and error by manually moving the utensil on the face (optic ataxia)[25][26]

Treatment

In terms of the specific rehabilitation of visuoperceptual disorders such as Bálint's syndrome, the literature is extremely sparse.[8] According to one study, rehabilitation training should focus on the improvement of visual scanning, the development of visually guided manual movements, and the improvement of the integration of visual elements.[10] Very few treatment strategies have been proposed, and some of those have been criticized as being poorly developed and evaluated.

Three approaches to rehabilitation of perceptual deficits, such as those seen in Bálint's syndrome, have been identified:

- The adaptive (functional) approach, which involves functional tasks utilising the person's strengths and abilities, helping them to compensate for problems or altering the environment to lessen their disabilities. This is the most popular approach.

- The remedial approach, which involves restoration of the damaged CNS by training in the perceptual skills, which may be generalised across all activities of daily living. This could be achieved by tabletop activities or sensorimotor exercises.

- The multi-context approach, which is based on the fact that learning is not automatically transferred from one situation to another. This involves practicing of a targeted strategy in a multiple environment with varied tasks and movement demands, and it incorporates self-awareness tasks.[26]

Case studies

Symptoms of Bálint's syndrome were found in the case of a 29-year-old with migraines. In the aura before the migraine headache, she experienced an inability to see all of the objects in the visual field simultaneously; an inability to coordinate hand and eye movements; and an inability to look at an object on command.[27] Symptoms were not present before the onset of the migraine or after it passed.

A study of a patient with Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration (CGBD) also showed a development of Bálint's syndrome. As a result of CGBD, the patient developed an inability to move his eyes to specific visual objects in his peripheral fields. He also was unable to reach out and touch objects in his peripheral fields. An inability to recognize more than one item at a time was also experienced when presented with the Cookie Theft Picture from the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination.[28]

A 58-year-old male presented with Bálint's syndrome secondary to severe traumatic brain injury 4-months post-injury onset. He had completed a comprehensive post-acute brain injury rehabilitation program. He received 6 months of rehabilitation services as an inpatient. A three-pronged approach included the implementation of (a) compensatory strategies, (b) remediation exercises and (c) transfer of learned skills in multiple environments and situations. Comprehensive neuropsychological and occupational therapy evaluations were performed at admission and at discharge. Neuropsychological test improvements were noted on tasks that assess visuospatial functioning, although most gains were noted for functional and physical abilities.[8]

A patient with congenital deafness exhibited partial Bálint's syndrome symptoms. This patient experienced an inability to perceive simultaneous events in her visual field. She was also unable to fixate and follow an object with her eyes. In addition, her ability to point at targets under visual guidance was impaired.[21]

Bálint's syndrome is rarely reported in children, but some recent studies provide evidence that cases do exist in children. A case involving a 10-year-old male child with Bálint's syndrome has been reported[29] Similar results were seen in a 7-year-old boy. In children this syndrome results in a variety of occupational difficulties, but most notably difficulties in schoolwork, especially reading. The investigators encourage more careful recognition of the syndrome to allow adequate rehabilitation and environmental adaptation.[30]

Criticism

The validity of Bálint's syndrome has been questioned by some. The components in the syndrome's triad of defects (simultanagnosia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia) each may represent a variety of combined defects.

Because Bálint's syndrome is not common and is difficult to assess with standard clinical tools, the literature is dominated by case reports and confounded by case selection bias, non-uniform application of operational definitions, inadequate study of basic vision, poor lesion localisation, and failure to distinguish between deficits in the acute and chronic phases of recovery.[12]

References

- Udesen, H; Madsen, A. L. (1992). "Balint's syndrome--visual disorientation". Ugeskrift for Laeger. 154 (21): 1492–4. PMID 1598720.

- synd/1343 at Who Named It?

- Bálint, Dr. (1909). "Seelenlähmung des 'Schauens', optische Ataxie, räumliche Störung der Aufmerksamkeit. pp. 51–66" [Soul imbalance of 'seeing', optical ataxia, spatial disturbance of attention. pp. 51–66]. European Neurology (in German). 25: 51–66. doi:10.1159/000210464.

- Bálint, Dr.; Zeeberg, I; Sjö, O (1909). "Seelenlähmung des 'Schauens', optische Ataxie, räumliche Störung der Aufmerksamkeit. pp. 67–81" [Soul imbalance of 'seeing', optical ataxia, spatial disturbance of attention. pp. 67-81]. European Neurology (in German). 25 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1159/000210465. PMID 3940867.

- Kerkhoff, G. (2000). "Neurovisual rehabilitation: Recent developments and future directions". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 68 (6): 691–706. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.6.691. PMC 1736971. PMID 10811691.

- Ribai, P.; Vokaer, M.; De Tiege, X.; Massat, I.; Slama, H.; Bier, J.C. (2006). "Acute Balint's syndrome is not always caused by a stroke". European Journal of Neurology. 13 (3): 310–2. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01144.x. PMID 16618355. S2CID 6567099.

- Perez, F. M.; Tunkel, R. S.; Lachmann, E. A.; Nagler, W. (2009). "Balint's syndrome arising from bilateral posterior cortical atrophy or infarction: Rehabilitation strategies and their limitation". Disability and Rehabilitation. 18 (6): 300–4. doi:10.3109/09638289609165884. PMID 8783001.

- Zgaljardic, Dennis J.; Yancy, Sybil; Levinson, Jason; Morales, Gabrielle; Masel, Brent E. (2011). "Balint's syndrome and post-acute brain injury rehabilitation: A case report". Brain Injury. 25 (9): 909–17. doi:10.3109/02699052.2011.585506. PMID 21631186. S2CID 207447734.

- Toyokura, M; Koike, T (2006). "Rehabilitative intervention and social participation of a case with Balint's syndrome and aphasia". The Tokai Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine. 31 (2): 78–82. PMID 21302228.

- Rosselli, Mónica; Ardila, Alfredo; Beltran, Christopher (2001). "Rehabilitation of Balint's Syndrome: A Single Case Report". Applied Neuropsychology. 8 (4): 242–7. doi:10.1207/S15324826AN0804_7. PMID 11989728. S2CID 969103.

- Rizzo, Matthew (2000). "Clinical Assessment of Complex Visual Dysfunction". Seminars in Neurology. 20 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1055/s-2000-6834. PMID 10874778.

- Rizzo, M (2002). "Psychoanatomical substrates of Balint's syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 72 (2): 162–78. doi:10.1136/jnnp.72.2.162. PMC 1737727. PMID 11796765.

- Dalrymple, Kirsten A.; Birmingham, Elina; Bischof, Walter F.; Barton, Jason J.S.; Kingstone, Alan (2011). "Experiencing simultanagnosia through windowed viewing of complex social scenes". Brain Research. 1367: 265–77. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.022. PMID 20950591. S2CID 9857024.

- Jackson, Georgina M.; Swainson, Rachel; Mort, Dominic; Husain, Masud; Jackson, Stephen R. (2009). "Attention, competition, and the parietal lobes: Insights from Balint's syndrome". Psychological Research. 73 (2): 263–70. doi:10.1007/s00426-008-0210-2. PMID 19156438. S2CID 26978283.

- Dalrymple, Kirsten A.; Bischof, Walter F.; Cameron, David; Barton, Jason J. S.; Kingstone, Alan (2010). "Simulating simultanagnosia: Spatially constricted vision mimics local capture and the global processing deficit". Experimental Brain Research. 202 (2): 445–55. doi:10.1007/s00221-009-2152-3. PMID 20066404. S2CID 23818496.

- Kim, Min-Shik; Robertson, Lynn C. (2001). "Implicit Representations of Space after Bilateral Parietal Lobe Damage". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 13 (8): 1080–7. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.299. doi:10.1162/089892901753294374. PMID 11784446. S2CID 18411954.

- https://aapos.org/terms/conditions/138%5B%5D%5B%5D

- Perenin, M.-T.; Vighetto, A. (1988). "Optic Ataxia: A Specific Disruption in Visuomotor Mechanisms". Brain. 111 (3): 643–74. doi:10.1093/brain/111.3.643. PMID 3382915.

- Battaglia-Mayer, A.; Caminiti, R. (2002). "Optic ataxia as a result of the breakdown of the global tuning fields of parietal neurones". Brain. 125 (2): 225–37. doi:10.1093/brain/awf034. PMID 11844724.

- "Health Content A-Z".

- Drane, Daniel L.; Lee, Gregory P.; Huthwaite, Justin S.; Tirschwell, David L.; Baudin, Brett C.; Jurado, Miguel; Ghodke, Basavaraj; Marchman, Holmes B. (2009). "Development of a Partial Balint's Syndrome in a Congenitally Deaf Patient Presenting as Pseudo-Aphasia". The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 23 (4): 715–28. doi:10.1080/13854040802448718. PMC 2836810. PMID 18923965.

- Valenza, Nathalie; Murray, Micah M.; Ptak, Radek; Vuilleumier, Patrik (2004). "The space of senses: Impaired crossmodal interactions in a patient with Balint syndrome after bilateral parietal damage". Neuropsychologia. 42 (13): 1737–48. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.05.001. PMID 15351624. S2CID 880666.

- Kas, A.; De Souza, L. C.; Samri, D.; Bartolomeo, P.; Lacomblez, L.; Kalafat, M.; Migliaccio, R.; Thiebaut De Schotten, M.; Cohen, L.; Dubois, B.; Habert, M.-O.; Sarazin, M. (2011). "Neural correlates of cognitive impairment in posterior cortical atrophy". Brain. 134 (5): 1464–78. doi:10.1093/brain/awr055. PMID 21478188.

- Benson, D. F.; Davis, R. J.; Snyder, B. D. (1988). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". Archives of Neurology. 45 (7): 789–93. doi:10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310107024. PMID 3390033.

- Rizzo, M (1993). "'Bálint's syndrome' and associated visuospatial disorders". Baillière's Clinical Neurology. 2 (2): 415–37. PMID 8137007.

- Al-Khawaja, I (2001). "Neurovisual rehabilitation in Balint's syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 70 (3): 416. doi:10.1136/jnnp.70.3.416. PMC 1737281. PMID 11248903.

- Shah, P. A; Nafee, A (1999). "Migraine aura masquerading as Balint's syndrome". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 67 (4): 554–5. doi:10.1136/jnnp.67.4.554. PMC 1736566. PMID 10610392.

- Mendez, M. F. (2000). "Corticobasal Ganglionic Degeneration with Balint's Syndrome". Journal of Neuropsychiatry. 12 (2): 273–5. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12.2.273. PMID 11001609.

- Gillen, Jennifer A; Dutton, Gordon N (2007). "Balint's syndrome in a 10-year-old male". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 45 (5): 349–52. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2003.tb00407.x. PMID 12729150.

- Drummond, Suzannah Rosalind; Dutton, Gordon N. (2007). "Simultanagnosia following perinatal hypoxia—A possible pediatric variant of Balint syndrome". Journal of American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 11 (5): 497–8. doi:10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.03.007. PMID 17933675.