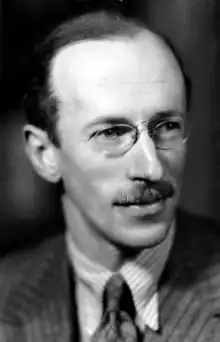

B. H. Liddell Hart

Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart (31 October 1895 – 29 January 1970), commonly known throughout most of his career as Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, was a British soldier, military historian, and military theorist. He wrote a series of military histories that proved influential among strategists. Arguing that frontal assault was bound to fail at great cost in lives, as proven in World War I, he recommended the "indirect approach" and reliance on fast-moving armoured formations.

Basil Liddell Hart | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 31 October 1895 Paris, France |

| Died | 29 January 1970 (aged 74) Marlow, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | St Peter and St Paul Churchyard, Medmenham, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Corpus Christi College, Cambridge |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier, military historian |

| Spouse |

Jessie Stone (m. 1918) |

| Children | Adrian Liddell Hart |

| Military career | |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1914 – 1927 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

His pre-war publications are known to have influenced German World War II strategy, though he was accused of prompting captured generals to exaggerate his part in the development of blitzkrieg tactics. He also helped promote the Rommel myth and the "clean Wehrmacht" argument for political purposes, when the Cold War necessitated the recruitment of a new West German army.

Life

Liddell Hart was born in Paris, the son of a Methodist minister.[1] His name at birth was Basil Henry Hart; he added "Liddell" to his surname in 1921.[2] His mother's side of the family, the Liddells, came from Liddesdale, on the Scottish side of the border with England, and were associated with the London and South Western Railway.[3] The Harts were farmers from Gloucestershire and Herefordshire.[4] As a child Liddell Hart was fascinated by aviation.[5] He received his formal academic education at Willington School in Putney, St Paul's School in London[1] and at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (where he was a student of Geoffrey Butler).

World War I

On the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Liddell Hart volunteered for the British Army, where he became an officer in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and served with the regiment on the Western Front. Liddell Hart's front line experience was relatively brief, confined to two short spells in the autumn and winter of 1915, being sent home from the front after suffering concussive injuries from a shell burst. He was promoted to the rank of captain. He returned to the front for a third time in 1916, in time to participate in the Battle of the Somme. He was hit three times without serious injury before being badly gassed and sent out of the line on 19 July 1916.[6] His battalion was nearly wiped out on the first day of the offensive on 1 July, a part of the 60,000 casualties suffered in the heaviest single day's loss in British history. The experiences he suffered on the Western Front profoundly affected him for the rest of his life.[7] Transferred to be adjutant of Volunteer units in Stroud and Cambridge which trained new recruits,[8] he wrote several booklets on infantry drill and training, which came to the attention of General Sir Ivor Maxse, commander of the 18th (Eastern) Division. After the war, he transferred to the Royal Army Educational Corps, where he prepared a new edition of the Infantry Training Manual. In it, Liddell Hart strove to instil the lessons of 1918, and carried on a correspondence with Maxse, a commanding officer during the battles of Hamel and Amiens.[9]

In April 1918 Liddell Hart married Jessie Stone, the daughter of J. J. Stone, who had been his assistant adjutant at Stroud,[10] and their son Adrian was born in 1922.[11]

Journalist and military historian

Liddell Hart was placed on half-pay from 1924.[12] He later retired from the Army in 1927. Two mild heart attacks in 1921 and 1922, probably the long-term effects of his gassing, precluded his further advancement in the small post-war army. He spent the rest of his career as a theorist and writer. In 1924, he became a lawn tennis correspondent and assistant military correspondent for The Morning Post covering Wimbledon and in 1926, publishing a collection of his tennis writings as The Lawn Tennis Masters Unveiled.[1] He worked as the military correspondent of The Daily Telegraph from 1925 to 1935 and of The Times from 1935 to 1939.

In the mid-to-late 1920s Liddell Hart wrote a series of histories of major military figures through which he advanced his ideas that the frontal assault was a strategy bound to fail at great cost in lives. He argued that the tremendous losses Britain suffered in the Great War were caused by its commanding officers not appreciating that fact of history. He believed the British decision in 1914 of directly intervening on the Continent with a great army was a mistake. He claimed that historically, "the British way in warfare" was to leave Continental land battles to her allies, intervening only through naval power, with the army fighting the enemy away from its principal front in a "limited liability" commitment.[13]

In his early writings on mechanised warfare, Liddell Hart had proposed that infantry be carried along with the fast-moving armoured formations. He described them as "tank marines" like the soldiers the Royal Navy carried with their ships. He proposed they be carried along in their own tracked vehicles and dismount to help take better-defended positions that otherwise would hold up the armoured units. That doctrine, similar to the mechanized infantry of later decades, contrasted with J.F.C. Fuller's ideas of a tank army, which put heavy emphasis on massed armoured formations. Liddell Hart foresaw the need for a combined arms force with mobile infantry and artillery, which was similar but not identical to the make-up of the panzer divisions that Heinz Guderian developed in Germany.[14]

According to Liddell Hart's memoirs, in a series of articles for The Times from November 1935 to November 1936, he had argued that Britain's role in the next European war should be entrusted to the air force. He theorised that Britain's air force could defeat her enemies while avoiding the high casualties and the limited influence that would come from Britain placing a large conscript army on the Continent.[15][16] The ideas influenced Neville Chamberlain, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, who argued in discussions of the Defence Policy and Requirements Committee for a strong air force, rather than a large army that would fight on the Continent.[17]

Becoming prime minister in 1937, Chamberlain placed Liddell Hart in a position of influence behind British grand strategy in the late 1930s.[18] In May, Liddell Hart prepared schemes for the reorganisation of the British Army for the defence of the British Empire and delivered them to Sir Thomas Inskip, Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence. In June, Liddell Hart gained an introduction to the Secretary of State for War, Leslie Hore-Belisha. Through July 1938 the two had an unofficial, close advisory relationship. Liddell Hart provided Hore-Belisha with ideas, which he would argue for in Cabinet or committees.[18] On 20 October 1937, Chamberlain wrote to Hore-Belisha, "I have been reading in Europe in Arms by Liddell Hart. If you have not already done so you might find it interesting to glance at this, especially the chapter on the 'Role of the British Army'". Hore-Belisha wrote in reply: "I immediately read the 'Role of the British Army' in Liddell Hart's book. I am impressed by his general theories".[19]

With the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the War Cabinet reversed the Chamberlain policy advanced by Liddell Hart. With Europe on the brink of war and Germany threatening an invasion of Poland, the cabinet chose instead to advocate a British and Imperial army of 55 divisions to intervene on the Continent by coming to the aid of Poland, Norway and France.[20]

Postwar

After the war, Liddell Hart was responsible for extensive interviews and debriefs for several high-ranking German generals, who were held by the Allies as prisoners-of-war. Liddell Hart provided commentary on their outlook. The work was published as The Other Side of the Hill (UK edition, 1948) and The German Generals Talk (condensed US edition, 1948).

A few years later, Liddell Hart had the opportunity to review the notes that Erwin Rommel had kept during the war. Rommel had kept the notes with the intention of writing of his experiences after the war; the Rommel family had previously published the notes in German as War without Hate in 1950. Some of the notes had been destroyed by Rommel, and the rest, including Rommel's letters to his wife, had been confiscated by the American authorities. With Liddell Hart's help, they were later returned to Rommel's widow. Liddell Hart then edited and condensed the book and helped integrate the new material. The writings, along with notes and commentary by former General Fritz Bayerlein and Liddell Hart, were published in 1953 as The Rommel Papers.[21] (See below for Liddell Hart's role in the Rommel myth.)

In 1954, Liddell Hart published his most influential work, Strategy.[22][23][24][n 1] It was followed by a second expanded edition in 1967. The book was largely devoted to a historical study of the indirect approach and in what ways various battles and campaigns could be analyzed using that concept. Still relevant at the turn of the century, it was a factor in the development of the British manoeuvre warfare doctrine.[26]

The Queen made Liddell Hart a Knight Bachelor in the New Year Honours of 1966.[27][28][29][30] As of 2009, Liddell Hart's personal papers and library form the central collection in the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King's College London.[31]

Liddell Hart died on 29 January 1970 at the age of 74 at his home in Marlow, Buckinghamshire.[32]

Key ideas and observations

[N]ot of one period but of its whole course, points to the fact that, in all decisive campaigns, the dislocation of the enemy's psychological and physical balance has been the vital prelude to his overthrow.

— B. H. Liddell Hart[33]

Liddell Hart was an advocate of the notion that it is easier to succeed in war by an indirect approach.[16][34] To attack where the opponent expects, as Liddell Hart explained, makes the task of winning harder: "To move along the line of natural expectation consolidates the opponent's balance and thus increases his resisting power". That is in contrast to an indirect approach, in which physical or psychological surprise is a component: "The indirectness is usually physical and always psychological. In strategy, the longest way round is often the shortest way home".

Liddell Hart would illustrate the notion with historical examples. For example, Liddell Hart considered the Battle of Leuctra, won by Epaminondas, an example of an indirect approach.[35] Rather than weighting his army on the right wing, as was standard at the time, Epaminondas weighted his left wing, held back his right wing and routed the Spartan army. A more modern example would be the landings of the Allies at Normandy on 6 June 1944, as the Germans were expecting a landing in the vicinity of Pas-de-Calais.[36] By contrast, an example of a direct attack, in Liddell Hart's eyes, was the attack by Union forces at the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862.[37]

Even more impressive in Liddell Hart's eyes was the further campaign by Epaminondas, his invasion of the Peloponnese, in which in winter and in separate columns, he invaded Spartan controlled territory.[38] He was unable to draw the Spartans into combat and so settled on freeing helots. He then built two city states as a break against Spartan power and so the campaign was successful. By breaking the Spartan economic base, he won a campaign without ever fighting a battle.

When analyzing the campaigns of Napoleon, Liddell Hart noted that his approaches were less subtle and more brute force as his forces became larger and that when his forces were lesser, he was more apt to be creative in his battles.[39] Constant victory seemed to have dulled his skills as a soldier.

According to Reid, Liddell Hart's indirect approach has seven key themes.:[40]

- The dislocation of the enemy's balance should be the prelude to defeat, not to utter destruction.

- Negotiate an end to unprofitable wars.

- The methods of the indirect approach are better suited to democracy.

- Military power relies on economic endurance. Defeating an enemy by beating him economically incurs no risk.

- Implicitly, war is an activity between states.

- Liddell Hart's notion of "rational pacifism".[41]

- Victory often emerges as the result of an enemy defeating itself.

Influence

During the 1960s Liddell Hart's reputation reached extraordinary heights. When he visited Israel in 1960 his trip stimulated more public interest than that of any other foreign visitor except Marilyn Monroe.

— Brian Holden Reid[42]

Liddell Hart's reputation as a military thinker stood very high at his death in 1970. Post-mortem assessments, however, have been more ambivalent.

— Christopher Bassford[43]

At the height of his popularity, John F. Kennedy called Liddell Hart "the Captain who teaches Generals" and was using his writings to attack the Eisenhower administration, which he said was too dependent on nuclear arms.[44][45] Liddell Hart influence extended to armies outside the UK and the US as well. Baumgarten stated of Liddell Hart's influence in the Australian Army: "The indirect approach was also one of the key influences on the development of manoeuvre theory, a dominant element in Army thinking throughout the 1990s".[46] Retired Pakistani General Shaafat Shah called Liddell Hart's book Strategy: the Indirect Approach "A seminal work of military history and theory".[47] In the book Science, Strategy and War, Frans Osinga mentioned while the Dutchman spoke of John Boyd, "In his recently published study of modern strategic theory, Colin Gray ranked Boyd among the outstanding general theorists of the strategy of the 20th century, along with the likes of Bernard Brodie, Edward Luttwak, Basil Liddell Hart and John Wylie".[48] His biographer, Alex Danchev, noted that Liddell Hart's books were still being translated all around the world, some of them 70 years after they had been written.[49]

Controversies

Influence on Panzerwaffe

Following the Second World War Liddell Hart pointed out that the German Wehrmacht adopted theories developed from those of J. F. C. Fuller and from his own, and that it used them against the Allies in Blitzkrieg warfare.[50] Some scholars, such as the political scientist John Mearsheimer, have questioned the extent of the influence which the British officers, and in particular Liddell Hart, had in the development of the method of war practised by the Panzerwaffe in 1939–1941. During the post-war debriefs of the former Wehrmacht generals, Liddell Hart attempted to tease out his influence on their war practices. Following these interviews, many of the generals said that Liddell Hart had been an influence on their strategies, something that had not been claimed previously nor has any contemporary, pre-war, documentation been found to support their assertions. Liddell Hart thus put "words in the mouths of German Generals" with the aim, according to Mearsheimer, to "resurrect a lost reputation".[51]

Shimon Naveh, the founder and former head of the Israel Defense Forces' Operational Theory Research Institute, stated that after World War II Liddell Hart "created" the idea of Blitzkrieg as a military doctrine: "It was the opposite of a doctrine. Blitzkrieg consisted of an avalanche of actions that were sorted out less by design and more by success."[52] Naveh stated that,

by manipulation and contrivance, Liddell Hart distorted the actual circumstances of the Blitzkrieg formation and obscured its origins. Through his indoctrinated idealization of an ostentatious concept, he reinforced the myth of Blitzkrieg. By imposing, retrospectively, his own perceptions of mobile warfare upon the shallow concept of Blitzkrieg, he created a theoretical imbroglio that has taken 40 years to unravel.[53]

Naveh stated that in his letters to German generals Erich von Manstein and Guderian, as well as to relatives and associates of Rommel, Liddell Hart "imposed his own fabricated version of Blitzkrieg on the latter and compelled him to proclaim it as original formula".[54]

Naveh pointed out that the edition of Guderian's memoirs published in Germany differed from the one published in the United Kingdom. Guderian neglected to mention the influence of the English theorists such as Fuller and Liddell Hart in the German-language versions. One example of the influence of these men on Guderian was the report on the Battle of Cambrai published by Fuller in 1920, who at the time served as a staff officer at the Royal Tank Corps. Liddell Hart alleged that his findings and theories on armoured warfare were read and later taken in by Guderian, which thus helped to formulate the basis of operations that would become known as Blitzkrieg warfare. These tactics involved deep penetration of the armoured formations supported behind enemy lines by bomb-carrying aircraft. Dive bombers were the principal agents of delivery of high explosives in support of the forward units.[55]

Though the German version of the Guderian memoirs mentions Liddell Hart, it did not ascribe to him his role in developing the theories behind armoured warfare. An explanation for the difference between the two translations can be found in the correspondence between the two men. In one letter to Guderian, Liddell Hart reminded the German general that he should provide him the credit he was due, offering "You might care to insert a remark that I emphasise the use of armoured forces for long-range operations against the opposing Army's communications, and also the proposed type of armoured division combining Panzer and Panzer-infantry units – and that these points particularly impressed you."[56]

Richard M. Swain comments that while some arguments against Liddell Hart's thinking are deserved, Liddell Hart the man himself was not a knave and Mearsheimer's attempt of character assassination is unwarranted.[57] Jay Luvaas comments that Liddell Hart and Fuller did actually anticipate the role of the armoured forces in a blitzkrieg. Luvaas opines that Liddell Hart did overestimate (in a sincere way) his influence on German generals, but the fact that many military leaders in Germany and other countries (including generals like Yigal Allon and Andre Beaufre) knew about his theories and considered his opinions as worth thinking about is true. According to Luvaas, von Mellenthin recounted that Rommel mentioned Liddell Hart many times and had a good opinion about him – although, in Luvaas's opinion, this would not make him a pupil. Luvass also sees Liddell Hart as a scholar who needed public recognition and influence, but also a naturally generous person whose efforts in building a connection to other people should not be assigned motives without evidence.[58] Joseph Forbes dismisses the claim that Liddell Hart, Guderian and Rommel's friends and relatives were in a conspiracy to misrepresent Liddell Hart's influence as baseless insinuations, considering that: Liddell Hart's chapter on Guderian quotes Guderian as having faith in the theories of Hobart and not of Liddell Hart; the fact Desmond Young once recommended Liddell Hart to Manfred Rommel as a person who might help to publish his father's memoirs should not be used as proof that there was a conspiracy to give undue recognition to Liddell Hart; the whole book The German Generals Talk contains one statement about Liddell Hart's influence. According to Forbes, Mearsheimer relies less on the actual text than on Frank Mahin's review to make the claim that Hart fills the book with fabricated comments by Germans to exaggerate his role.[59]

Role in Rommel myth

Liddell Hart was instrumental in the creation of the "Rommel myth", a view that the German field marshal Erwin Rommel was an apolitical, brilliant commander and a victim of the Third Reich due to his participation in the 20 July plot against Adolf Hitler.

The myth was initially fueled by Nazi propagandists, with Rommel's participation, as a means of praising the Wehrmacht and instilling optimism in the German public. Starting in 1941, it was picked up by the British press and disseminated in the West as an element of explaining Britain’s continued inability to defeat the Axis forces in the North Africa campaign.

Following the war, the Western Allies, and particularly the British, depicted Rommel as the "good German" and "our friend Rommel". His reputation for conducting a clean war was used to support West German rearmament and reconciliation between the former enemies – Britain and the United States on one side and the new Federal Republic on the other.[60][61][62]

After the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, it became clear to the Americans and the British that a German army would have to be revived to help face off against the Soviet Union. Many former German officers were convinced, however, that no future German army would be possible without the rehabilitation of the Wehrmacht.[63] Thus, in the atmosphere of the Cold War, Rommel's former enemies, especially the British, played a key role in the manufacture and propagation of the myth.[64] The German rearmament was highly dependent on the image boosting that the Wehrmacht needed. Liddell Hart, an early proponent of these two interconnected initiatives, provided the first widely available source on Rommel in his 1948 book on Hitler's generals. He devoted a chapter to Rommel, portraying him as an outsider to the Nazi regime. Additions to the chapter published in 1951 concluded with laudatory comments about Rommel's "gifts and performance" that "qualified him for a place in the role of the 'Great Captains' of history".[65]

1953 saw the publication of Rommel's writings of the war period as The Rommel Papers, edited by Liddell Hart, the former Wehrmacht officer Fritz Bayerlein, and Rommel's widow and son, with an introduction by Liddell Hart. The historian Mark Connelly argues that The Rommel Papers was one of the two foundational works that lead to a "Rommel renaissance", the other being Desmond Young's biography Rommel: The Desert Fox.[66][n 2] The book contributed to the perception of Rommel as a brilliant commander; in an introduction, Liddell Hart drew comparisons between Rommel and Lawrence of Arabia, "two masters of desert warfare", according to Liddell Hart.[67] Liddell Hart's work on the book was also self-serving: he had coaxed Rommel's widow into adding material that suggested that Rommel was influenced by Liddell Hart's theories on mechanised warfare, making Rommel his "pupil" and giving Liddell Hart credit for Rommel's dramatic successes in 1940.[68] (The controversy was described by the political scientist John Mearsheimer in his work The Weight of History.[68] A review of Mearsheimer's work, published by the Strategic Studies Institute, points out that Mearsheimer "correctly takes 'The Captain' [Liddell Hart] to task for ... manipulating history".)[51]

According to Connelly, Young and Liddell Hart laid the foundation for the Anglo-American myth, which consisted of three themes: Rommel's ambivalence towards Nazism; his military genius; and the emphasis of the chivalrous nature of the fighting in North Africa.[66] Their works lent support to the image of the "clean Wehrmacht" and were generally not questioned, since they came from British authors, rather than German revisionists.[69][n 3]

MI5 controversy

On 4 September 2006, MI5 files were released which showed that in early 1944 MI5 had suspicions that plans for the D-Day invasion had been leaked. Liddell Hart had prepared a treatise titled Some Reflections on the Problems of Invading the Continent which he circulated amongst political and military figures. It is possible that in his treatise Liddell Hart had correctly deduced a number of aspects of the upcoming Allied invasion, including the location of the landings. MI5 suspected that Liddell Hart had received plans of the invasion from General Sir Alfred "Tim" Pile who was in command of Britain's anti-aircraft defences. MI5 placed him under surveillance, intercepting his telephone calls and letters. The investigation showed no suggestion that Liddell Hart was involved in any subversive activity. No case was ever brought against Pile. Liddell Hart stated his work was merely speculative. It would appear that Liddell Hart had simply perceived the same problems and arrived at similar conclusions as the Allied general staff.[71][72]

Biographies

- Alex Danchev wrote the biography of Liddell Hart, Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart, with the cooperation of Liddell Hart's widow.

- Brian Bond wrote Liddell Hart: a study of his military thought (Cassell, 1977; Rutgers University Press, 1977).

- John J. Mearsheimer's Liddell Hart and the Weight of History (New York, 1988), published by the Cornell University Press and part of the Cornell Studies in Security Affairs, uses primary evidence to look at Liddell Hart's claims to have predicted the fall of France by Blitzkrieg tactics and that he was influential with German generals and thinkers (notably Guderian and Rommel) in the 1930s. What emerges are serious questions as to Liddell Hart's version of history.[51]

Works

- Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (originally: A Greater than Napoleon: Scipio Africanus; W Blackwood and Sons, London, 1926; Biblio and Tannen, New York, 1976)

- Lawn Tennis Masters Unveiled (Arrowsmith, London, 1926)

- Great Captains Unveiled (W. Blackwood and Sons, London, 1927; Greenhill, London, 1989)

- Reputations 10 Years After (Little, Brown, Boston, 1928)[73]

- Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American (Dodd, Mead and Co, New York, 1929; Frederick A. Praeger, New York, 1960)

- The Decisive Wars of History (1929) (This is the first part of the later: Strategy: The Indirect Approach)

- The Real War 1914–1918 (1930), reprinted as A History of the World War 1914-1918 (1934); later republished as History of the First World War (1970).

- Foch: The Man of Orleans in two volumes (1931), Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, England.

- The Ghost of Napoleon (Yale University, New Haven, 1934)

- T.E. Lawrence in Arabia and After (Jonathan Cape, London, 1934 – online)

- World War I in Outline (1936)

- The Defence of Britain (Faber and Faber, London, Fall 1939 (after the German war against Poland); Greenwood, Westport, 1980). German edition:

- Die Verteidigung Gross-Britanniens. Zürich 1939.

- The Current of War, London: Hutchinson, 1941

- The Strategy of Indirect Approach (1941, reprinted in 1942 under the title: The Way to Win Wars)

- The Way to Win Wars (1942)

- Why Don't We Learn From History?, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1944

- The Revolution in Warfare, London: Faber and Faber, 1946

- The Other Side of the Hill: Germany's Generals. Their Rise and Fall, with their own Account of Military Events 1939–1945, London: Cassel, 1948; enlarged and revised edition, Delhi: Army Publishers, 1965

- The Letters of Private Wheeler 1809-1828, (editor), London: Michael Joseph, 1951

- "Foreword" to Heinz Guderian's Panzer Leader (New York: Da Capo., 1952)

- Strategy, second revised edition, London: Faber and Faber, 1954, 1967.

- The Rommel Papers, (editor), 1953

- The Tanks – A History of the Royal Tank Regiment and its Predecessors: Volumes I and II (Praeger, New York, 1959)

- "Foreword" to Samuel B. Griffith's Sun Tzu: the Art of War (Oxford University Press, London, 1963)

- The Memoirs of Captain Liddell Hart: Volumes I and II (Cassell, London, 1965)

- History of the Second World War (London, Weidenfeld Nicolson, 1970)

- The German Generals Talk: Startling Revelations from Hitler's High Command (1971 ed.). William Morrow. 1948. ISBN 9780688060121.

References

Notes

- This history of this work is involved, as it has multiple titles and editions. Later versions are known as Strategy: The Indirect Approach as well. Danchev notes the first version was developed in 1929 and was rewritten and updated in 1941, 1946, 1954, and 1967.[25]

- Connelly also uses the term "Anglophone rehabilitation".[66]

- Kitchen: "The North African campaign has usually been seen, as in the title of Rommel's account, as 'War without Hate', and thus as further proof that the German army was not involved in any sordid butchering, which was left to Himmler's SS. While it was perfectly true that the German troops in North Africa fought with great distinction and gallantry, ... it was fortunate for their subsequent reputation that the SS murderers that followed in their wake did not have an opportunity to get to work." Kitchen further explains that the sparsely populated desert areas did not lend themselves to ethnic cleansing; that the German forces never reached Egypt and Palestine that had large Jewish populations; and that, in the urban areas of Tunisia and Tripolitania, the Italian government constrained the German efforts to discriminate against or eliminate Jews who were Italian citizens.[70]

Citations

- "Hart, Sir Basil Henry Liddell". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014.

- Whittle, Marius Gerard Anthony. "Deceiving Clio: A Critical Examination of the Writing of Military History in the Pursuit of Military Reform and Modernisation (with Particular Reference to Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart and Major General John Frederick Charles Fuller)". M.A. thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 2009, 63.

- Wrigley, Chris (2002). Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 215. ISBN 0874369908.

- Bond p. 12

- Bond p. 13

- Bond pp. 16–17

- Bond p. 16

- Bond p. 19

- Bond p. 25

- Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart, The memoirs of Captain Liddell Hart: Volume 1 (1965 edition), p. 31: "In April I married the younger daughter, Jessie, of my former assistant adjutant at Stroud, J. J. Stone..."

- Liddell Hart, Adrian John (1922–1991) Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine at aim25.ac.uk, accessed 3 May 2011

- Bond p. 32

- Barnett, p. 503.

- Bond p. 29

- Liddell Hart, Memoirs, Vol I, pp. 296–299, pp. 380–381.

- Alex Danchev, , "Liddell Hart and the Indirect Approach", Journal of Military History, 63#2 (1999), pp. 313–337.

- Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (London: Methuen, 1972), pp. 497–499.

- Barnett, p. 502.

- Minney p. 54

- Barnett, p. 576.

- Major 2008.

- Shah, Shafat U, In Defense of Liddell Hart's 'Strategy Archived 20 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Task and Purpose, Nov 2018.

- Reid, Brian Holden, The Legacy of Liddell Hart: The Contrasting Responses of Michael Howard and André Beaufre Archived 3 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, British Journal for Military History, Volume 1, Issue 1, October 2014, p. 67

- Marshall, S.L.A. (29 August 1954). "New Looks and Old". The New York Times. New York, New York, USA. p. 100,118. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Danchev, Alex, Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998, pp. 156–157

- Danchev, Alchemist of War, p. 157

- "new knight Liddell Hart weighs cost in Vietnam". The Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario, Canada. Associated Press. 4 January 1966. p. 10. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Teaching The Enemy". The Boston Globe. Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 4 September 1666. p. 24. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Watts, Granville (1 January 1966). "Acid Penned Writer Wins Knighthood". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon, USA. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Novelists Greene and Golding Named on Queen's Honors List". The New York Times. New York, New York, USA. 1 January 1966. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Liddell Hart archive, KCL". Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- "Basil Liddell Hart, 74, Is Dead; Military Theorist and Writer". The New York Times. 30 January 1970. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Brian Bond, Liddell-Hart: A Study of His Military Thought, London: Casell, 1979. p. 55

- Liddell Hart, B.H., Strategy, Faber and Faber, 1967, pp. 5–6.

- Liddell Hart, Strategy, pp. 14–16.

- Liddell Hart, Strategy, pp. 294–299.

- Liddell Hart, Strategy, p. 128

- Liddell Hart, Strategy, 1967, pp. 14–15

- Liddell Hart, Basil, Strategy, pp. 119–123

- Reid, Brian Holden, pp. 68–69

- Danchev, Alex, Alchemist of War, pp. 167–168

- Brian Holden Reid, p. 67.

- Bassford, Christopher, Clausewitz in English: The Reception of Clausewitz in Britain and America,Clausewitz in English, Oxford University Press, 1994, Chapter 15.

- Reid, Brian Holden, p. 69

- Bassford, Christopher, Chapter 15.

- Baumgarten, Sam, Australian Army Journal, Summer, Volume XI, No 2, p. 64

- Shah, Shaffat U, ibid

- Osinga, Franz, Science, Strategy, and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd, Routledge, 2006, p. 3

- Danchev, Alex, Alchemist of War, p. 5

- Naveh p. 107.

- Luvaas 1990.

- Naveh 1997, pp. 107–108.

- Naveh 1997, pp. 108–109.

- Naveh 1997, p. 109.

- Corum p. 42

- Danchev 1998, pp. 234–235.

- Swain, Richard M. (1991). "Reviewed Work: Liddell Hart and the Weight of History by John J. Mearsheimer". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. 23 (4 (Winter, 1991)): 801–804. doi:10.2307/4050797. JSTOR 4050797. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Luvaas 1990, pp. 9–19.

- Forbes, Joseph (1990). "Review Reviewed Work: Liddell Hart and the Weight of History. by John J. Mearsheimer". The Journal of Military History. 54 (3 (Jul., 1990)): 368–370. doi:10.2307/1985958. JSTOR 1985958. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Searle 2014, pp. 8–27.

- Caddick-Adams 2012, p. 471-478.

- Major 2008, p. 520-535.

- Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 72–73.

- Caddick-Adams 2012, p. 471–472.

- Searle 2014, pp. 8, 27.

- Connelly 2014, pp. 163–163.

- Major 2008, p. 526.

- Mearsheimer 1988, pp. 199–200.

- Caddick-Adams 2012, p. 483.

- Kitchen 2009, p. 10.

- "Files reveal leaked D-Day plans". BBC News. 4 September 2006.

- Michael Evans (4 September 2006). "Army writer nearly revealed plans of D-Day". The Times. London.

- Bakeless, John (1 April 1928). "Reputations Ten Years After". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Baumgarten, Sam. "Sir Basil Liddell Hart's influence on Australian military doctrine." Archived 19 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine Australian Army Journal 11.2 (2014): 64+

- Bond, Brian, Liddell Hart: A Study of his Military Thought. London: Cassell, 1977.

- Caddick-Adams, Peter (2012). Monty and Rommel: Parallel Lives. New York, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN 9781590207253.

- Chambers, Madeline (2012). "The Devil's General? German film seeks to debunk Rommel myth". Reuters. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Connelly, Mark (2014). "Rommel as Icon". In Beckett, F. W. (ed.). Rommel Reconsidered. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1462-4.

- Cook, Joseph J. "From Liddell Hart to Keegan: Examining the Twentieth Century Shift in Military History Embodied by Two British Giants of the Field." Saber and Scroll 4.2 (2015): 4.

- Corum, James S. The Roots of Blitzkrieg: Hans von Seeckt and German Military Reform (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1992). ISBN 0-7006-0541-X.

- Danchev, Alex, Alchemist of War: The Life of Basil Liddell Hart. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998). ISBN 0-7538-0873-0

- Danchev, Alex, "Liddell Hart and the Indirect Approach", Journal of Military History, Vol. 63, No. 2. (1999), pp. 313–337.

- Gat, Azar. Fascist and liberal visions of war: Fuller, Liddell Hart, Douhet, and other modernists (Courier Corporation, 1998).

- Gibson, Charles M.; Commander, USN (2001). "Operational Leadership as Practiced by Field Marshall Erwin Rommel During the German Campaign in North Africa 1941–1942: Success of Failure?" (PDF). Naval War College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Kitchen, Martin (2009). Rommel's Desert War: Waging World War II in North Africa, 1941–1943. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-50971-8.

- Luvaas, Jay (1990). "Liddell Hart and the Mearsheimer Critique: A "Pupil's" Retrospective" (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Larson, Robert H. "BH Liddell Hart: Apostle of Limited War." Military Affairs 44.2 (1980): 72+ in JSTOR

- Luvaas, Jay. "Clausewitz, Fuller and Liddell Hart." Journal of Strategic Studies 9.2–3 (1986): 197–212.

- Major, Patrick (2008). "'Our Friend Rommel': The Wehrmacht as 'Worthy Enemy' in Postwar British Popular Culture". German History. Oxford University Press. 26 (4): 520–535. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghn049.

- Mearsheimer, John (1988). Liddell Hart and the Weight of History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-2089-X.

- von Mellenthin, Friedrich (1955). Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-345-32158-9.

- Naveh, Shimon, In Pursuit of Military Excellence; The Evolution of Operational Theory. (London: Francass, 1997). ISBN 0-7146-4727-6.

- Reid, Brian Holden. "'Young Turks, or Not So Young?': The Frustrated Quest of Major General JFC Fuller and Captain BH Liddell Hart." The Journal of Military History 73.1 (2009): 147–175. online

- Robinson, James R. (1997). "The Rommel Myth". Military Review Journal. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- Searle, Alaric (2014). "Rommel and the Rise of the Nazis". In Beckett, F. W. (ed.). Rommel Reconsidered. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-1462-4.

- Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83365-3.

- Swain, Richard M. "BH Liddell Hart and the Creation of a Theory of War, 1919-1933." Armed Forces & Society 17.1 (1990): 35–51.