London and South Western Railway

The London and South Western Railway (LSWR, sometimes written L&SWR) was a railway company in England from 1838 to 1922. Originating as the London and Southampton Railway, its network extended to Dorchester and Weymouth, to Salisbury, Exeter and Plymouth, and to Padstow, Ilfracombe and Bude. It developed a network of routes in Hampshire, Surrey and Berkshire, including Portsmouth and Reading.

_(14778864773).jpg.webp) LSWR boat train about 1911 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | London Waterloo station |

| Locale | England |

| Dates of operation | 1840–1922 |

| Predecessor | London and Southampton Railway |

| Successor | Southern Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The LSWR became famous for its express passenger trains to Bournemouth and Weymouth, and to Devon and Cornwall. Nearer London it developed a dense suburban network and was pioneering in the introduction of a widespread suburban electrified passenger network. It was the prime mover of the development of Southampton Docks, which became an important ocean terminal as well as a harbour for cross channel services and for Isle of Wight ferries. Although the LSWR's area of influence was not the home of large-scale heavy industry, the transport of goods and mineral traffic was a major activity, and the company built a large marshalling yard at Feltham. Freight, docks and shipping business provided almost 40 per cent of turnover by 1908. The company handled the rebuilding of London Waterloo station as one of the great stations of the world, and the construction of the Waterloo & City line, giving access to the City of London. The main line was quadrupled and several of the junctions on it were given grade-separation. It pioneered the introduction of power signalling. In the Boer War its connections at Aldershot, Portland, and on Salisbury Plain, made it a vital part of the war effort, and later during the First World War it successfully handled the huge volume of traffic associated with bringing personnel, horses and equipment to the English channel ports, and the repatriation of the injured. It was a profitable company, paying a dividend of 5% or more from 1871.

Following the Railways Act 1921 the LSWR amalgamated with other railways to create the Southern Railway, on 1 January 1923, as part of the grouping of the railways. It was the largest constituent: it operated 862 route miles, and was involved in joint ventures that covered a further 157 miles. In passing its network to the new Southern Railway, it showed the way forward for long-distance travel and outer-suburban passenger operation, and for maritime activity. The network continued without much change through the lifetime of the Southern Railway, and for some years following nationalisation in 1948. In Devon and Cornwall the LSWR routes duplicated former Great Western Railway routes, and in the 1960s they were closed or substantially reduced in scope. Some unsuccessful rural branch lines nearer the home counties closed too in the 1960s and later, but much of the LSWR network continues in busy use to the present day.

The first main line

The London and South Western Railway arose out of the London and Southampton Railway (L&SR), which was promoted to connect Southampton to the capital; the company envisaged a considerable reduction in the price of coal and agricultural necessities to places served, as well as imported produce through Southampton Docks, and passenger traffic.

Construction probably started on 6 October 1834 under Francis Giles, but progress was slow. Joseph Locke was brought in as engineer, and the rate of construction improved; the first part of the line opened to the public between Nine Elms and Woking Common on 21 May 1838,[1] and it was opened throughout on 11 May 1840. The terminals were at Nine Elms, south of the River Thames and a mile or so southwest of Trafalgar Square, and a terminal station at Southampton close to the docks, which were also directly served by goods trains.[2]

The railway was immediately successful, and road coaches from points further west altered their routes so as to connect with the new railway at convenient interchange points, although goods traffic was slower to develop.[3]

Branch to Gosport, and change of name

The London and Southampton Railway promoters had intended to build a branch from Basingstoke to Bristol, but this proposal was rejected by Parliament in favour of the competing route proposed by the Great Western Railway. The parliamentary fight had been bitter, and a combination of resentment and the commercial attraction of expanding westwards remained in the company's thoughts.[4]

A more immediate opportunity was taken up, of serving Portsmouth by a branch line. Interests friendly to the L&SR promoted a Portsmouth Junction Railway, which would have run from Bishopstoke (Eastleigh) via Botley and Fareham to Portsmouth. However antagonism in Portsmouth—which considered Southampton a rival port—at being given simply as branch and thereby a roundabout route to London, killed the prospects of such a line. Portsmouth people wanted their own direct line, but in trying to play off the L&SR against the London and Brighton Railway they were unable to secure the committed funds they needed.

The L&SR now promoted a cheaper line to Gosport, on the opposite side of Portsmouth Harbour, shorter and simpler than the earlier proposal, but requiring a ferry crossing. Approval had recently been given for the construction of a so-called floating bridge, a chain ferry, which started operation in 1840.[5] The ferry would give an easy transit across Portsmouth Harbour, and the L&SR secured its Act of Parliament on 4 June 1839. To soothe feelings in Portsmouth, the L&SR included in its bill a change of name to the London and South Western Railway under Section 2.[6]

Construction of the Gosport branch was at first quick and simple under the contractor Thomas Brassey. Stations were built at Bishopstoke (the new junction station; later renamed Eastleigh) and Fareham. An extremely elaborate station was built at Gosport, tendered at £10,980, seven times the tender price for Bishopstoke. However, there was a tunnel at Fareham, and on 15 July 1841 there was a disastrous earth slip at the north end. Opening of the line had been advertised for 11 days later, but the setback forced a delay until 29 November; the ground slipped again four days later, and passenger services were suspended until 7 February 1842.[6]

With train services to Gosport operating, Isle of Wight ferry operators altered some sailings to leave from Gosport instead of Portsmouth. Queen Victoria was fond of travelling to Osborne House on the island, and on 13 September 1845 a 605 yd (553 m) branch to the Royal Clarence Victualling Establishment, where she could transfer from train to ship privately, was opened for her convenience.[7][8][9]

Gauge wars

Between the first proposal for a railway from London to Southampton and the construction, interested parties were considering rail connections to other, more distant, towns that might be served by extensions of the railway. Reaching Bath and Bristol via Newbury was an early objective. The Great Western Railway (GWR) also planned to reach Bath and Bristol, and it obtained its Act of Parliament on 31 August 1835, which for the time being removed those cities from the LSWR's immediate plans. There remained much attractive territory in the South West, the West of England, and even the West Midlands, and the LSWR and its allies continually fought the GWR and its allies to be the first to build a line in a new area.

The GWR was built on the broad gauge of 7 ft 1⁄4 in or 2,140 mm while the LSWR gauge was standard gauge (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in or 1,435 mm), and the allegiance of any proposed independent railway was made clear by its intended gauge. The gauge was generally specified in the authorising Act of Parliament, and bitter and protracted competition took place to secure authorisation for new lines of the preferred gauge, and to bring about parliamentary rejection of proposals from the rival faction. This rivalry between the GWR and the standard gauge companies became called the gauge wars.

In the early days government held that several competing railways could not be sustained in any particular area of the country, and a commission of experts referred to informally as the "Five Kings" was established by the Board of Trade to determine the preferred development, and therefore the preferred company, in certain districts, and this was formalised in the Railway Regulation Act 1844.[10]

Suburban lines

The LSWR was the second British railway company to begin running a commuter service, after the London and Greenwich Railway, which opened in 1836.[11]

When the LSWR opened its first main line, the company built a station called Kingston, somewhat to the east of the present-day Surbiton station, and this quickly attracted business travel from residents of Kingston upon Thames. The availability of fast travel into London encouraged new housing development close to the new station. Residents of Richmond upon Thames observed the popularity of this facility, and promoted the Richmond Railway from Richmond to Waterloo. The LSWR took over the construction of the extension from Nine Elms to Waterloo itself, and the line from Richmond to Falcon Bridge, at the present-day Clapham Junction, opened in July 1846. The line became part of the LSWR later that year. Already a suburban network was developing, and this gathered pace in the following decades.[12]

The Chertsey branch line opened from Weybridge to Chertsey on 14 February 1848.[13] The Richmond line was extended, reaching Windsor in 1849,[14] while a loop line from Barnes via Hounslow rejoining the Windsor line near Feltham had been opened in 1850.[15] In 1856 a friendly company, the Staines, Wokingham and Woking Junction Railway, opened its line from Staines to Wokingham, and running powers over the line shared by the South Eastern Railway and the Great Western Railway gave access for LSWR trains over the remaining few miles from Wokingham to Reading.

The Hampton Court branch line was opened on 1 February 1849.[16]

South of the main line, the LSWR wished to connect to the important towns of Epsom and Leatherhead. In 1859 the friendly Wimbledon and Dorking Railway opened from Wimbledon, running alongside the main line as far as Epsom Junction, at the site of the later Raynes Park station, then diverging to Epsom, joining there the Epsom and Leatherhead Railway, operated jointly with the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway.[17]

Parts of Kingston were three miles (4.8 kilometres) from Surbiton station but in 1863 a line from Twickenham to Kingston railway station (England) was opened, forming the first part of the Kingston loop line. A single-track Shepperton branch line was laid in 1864, reaching westwards up the Thames Valley. In 1869 the Kingston loop line was completed by the south-eastward extension from Kingston to Wimbledon, with its own dedicated track alongside the main line from Malden to Epsom Junction (Raynes Park), where it joined the former Wimbledon and Dorking Railway lines.[18]

London terminal stations

Nine Elms

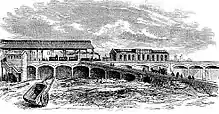

The company's first London terminus was at Nine Elms on the southwestern edge of the built-up area. The wharf frontage on the Thames was advantageous to the railway's objective of competing with coastal shipping transits, but the site was inconvenient for passengers, who had to travel to or from London either by road or by steamer.

Passenger steamboats left from Old Swan Pier, Upper Thames Street, not very close to the City centre but the best that could be managed, one hour before the departure of each train from Nine Elms, and called at several intermediate piers on the way. To take one hour and only get as far as the starting point of the train was clearly not good enough, not even 150 years ago.[19]

Extending to Waterloo

The "Metropolitan Extension" to a more central location had been discussed as early as 1836, and a four-track extension was authorised from Nine Elms to what became Waterloo station, at first called Waterloo Bridge station. Opening was planned for 30 June 1848, but the Board of Trade inspector Captain Simmonds was concerned about the structural stability of Westminster Bridge Road Bridge, and required a load test. This was carried out on 6 July 1848, and was satisfactory. The line opened on 11 July 1848, together with the four tracks from Nine Elms in to Waterloo.[20][21][22]

Waterloo station occupied three-quarters of an acre (0.3ha); there were two centre lines, and four other lines serving roofed platforms 300 ft (91m) long, soon after extended to 600 ft (182m). They were located approximately where platforms 9 to 12 are today. Only temporary buildings were provided at first, but permanent structures opened in 1853. At first incoming trains stopped outside the station, the locomotive was detached and the carriages were allowed to roll into one of the platforms while the guard controlled the brake.[23] The Nine Elms site became dedicated to goods traffic and was much extended to fill the triangle of land eastwards to Wandsworth Road.[21][22]

Development of Waterloo Station

Over the rest of the LSWR's existence Waterloo station was gradually extended and improved. Expanding its footprint in a heavily built-up area was expensive and slow. Four extra platforms were opened on 3 August 1860 on the north-west side of the original station, but separated from it by the cab road. These extended as far as what is today platform 16 and were always known as the Windsor station. There was an extra track between platforms 2 and 3 and this was the line connecting to the South Eastern Railway; it opened on 1 July 1865.[22]

The South Station was brought into use on 16 December 1878; it had two new tracks and a double sided platform; the original station now became known as the Central station, while in November 1885 the North Station was opened by extending from the Windsor station towards York Road. It had six new platform faces, so that the total was now 18 platforms, two in the South, six in the Central, four in the Windsor, and six in the North, a total area of 16 acres (6.5ha).

Two more tracks were added down the main line from Waterloo to Nine Elms between 1886 and 1892; the seventh line was added on the east side on 4 July 1900, and the eighth in 1905. New platforms 1 to 3 were opened to traffic on 24 January 1909, followed by platform 4 on 25 July 1909 and platform 5 on 6 March 1910. New platforms 6 to 11 followed in 1913.[22] In 1911 the new four storey frontage block was ready; at last Waterloo had an integrated building for passengers' requirements, staff accommodation and offices. There was a new roof over platforms 1 to 15; platforms 16 to 21 retained their original 1885 roof.[22] Other platforms were rearranged and renewed; beyond the cab road platforms 12 to 15 were allocated to main line arrivals, opening in 1916. The station reconstruction was eventually finished in 1922; the cost of the reconstruction had been £2,269,354. It was officially opened by Queen Mary on 21 March 1922.[22]

London Necropolis Company

Following the cholera outbreak of 1848–1849 in London, it was clear that there was a scarcity of burial plots in suburban London. The London Necropolis Company was established in 1852; it set up a cemetery in Brookwood served by a short branch line off the LSWR main line. At Waterloo it built a dedicated station on the south side of the LSWR station, opening it in 1854. It was independent of the LSWR, but it chartered daily funeral trains to from Waterloo to Brookwood for mourners and the deceased. First, second and third class accommodation was provided on the trains. The Necropolis Station was demolished and replaced by a new one beyond Westminster Bridge Road railway bridge; its new station had two platforms, and opened on 16 February 1902.[22]

To Cannon Street over the South Eastern Railway

Continuing to wish to have access to the City of London, the LSWR tried repeatedly to get access independently, but these plans were dropped on the grounds of expense. The Charing Cross Railway (CCR), supported by the South Eastern Railway (SER), opened a line from London Bridge to Charing Cross on 11 January 1864, and was obliged by the terms of its authorising Act to make a connection from that line to the LSWR Waterloo station. It did so but at first declined to operate any trains over the connection.

The single line connected through the station concourse and ran between platforms 2 and 3; there was a movable bridge across the track. On 6 July 1865 a circular service started from Euston via Willesden and Waterloo to London Bridge. The SER was clearly reluctant to encourage this service, and diverted to Cannon Street it struggled on until ceasing on 31 December 1867. A few van shunts, and also the Royal Train, were the only movements over the line after that.[27][28]

To Ludgate Hill over the LC&DR

The inconvenience of the location of Waterloo as a London terminal continued to exercise the Board of the LSWR. At this time the London, Chatham and Dover Railway was building its own line to the city, but was in financial difficulty having overreached itself. It therefore welcomed an approach from the LSWR to use its Ludgate Hill station in the City of London, when a financial contribution was on offer.[29]

Trains from the direct Richmond line via Barnes could access the Longhedge line at Clapham Junction, running through to Ludgate Hill by way of Loughborough Junction. This route became available on 3 April 1866. On 1 January 1869, the Kensington and Richmond line of the LSWR was ready: this ran from Richmond by way of Gunnersbury and Hammersmith to Kensington. Trains ran from there via the West London Extension Railway, then reaching the LCDR at Longhedge Junction. From there Ludgate Hill was accessible via Loughborough Junction.[30][31] The Kingston to Malden link also opened on 1 January 1869; running through independently of the main line to Wimbledon, it joined the Epsom line at Epsom Junction, later Raynes Park station. The Kingston and Epsom lines ran to a separate station at Wimbledon at first; this was integrated into the main Wimbledon station during 1869. The platforms used by those trains were also to be connected to the Tooting, Merton and Wimbledon Railway which was under construction.[32]

The Tooting line connected into the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway at Streatham Junction, and the LCDR was building a connection from its Herne Hill station to Knights Hill Junction, on the LBSCR three miles north of Streatham Junction. The LCDR connection gave direct access to Ludgate Hill, and friendly relations now existed between the LSWR and the LBSCR, such that running powers were agreed to bridge the gap. All the route sections were ready and LSWR trains started using the route on 1 January 1869.[29][33][34]

Tube line to the City

The LSWR continued to be concerned about the remoteness of Waterloo from the City of London. The approaches to Ludgate Hill via Loughborough Junction were circuitous and slow, and inaccessible to passengers using main line trains, and outer suburban trains, at Waterloo. The City and South London Railway opened in 1890 as a deep level tube railway. Although it had limitations, it showed the idea to be practical and popular, and the LSWR saw that this was a way forward.

The company encouraged the development of a tube railway from Waterloo to a "City" station, later renamed "Bank". The LSWR sponsored a nominally independent company to construct the line, and the Waterloo and City Railway Company was incorporated by Act of Parliament of 27 July 1893.[35] The line was only the second bored tube railway in the world; it was electrified, and was 1+1⁄2 miles (3 km) in length; it opened to the public on 8 August 1898. The LSWR absorbed it in 1907.[36]

Portsmouth and Alton routes

The LSWR's dominant route to Portsmouth was what became the Portsmouth Direct Line, its importance enhanced by the development of leisure travel to the Isle of Wight. Alton followed, later encouraging a local network for the Aldershot military depots, and itself forming a hub for secondary routes.

Portsmouth

The London and Southampton Railway opened in 1838, part of the way, and in 1840 throughout.[1] Its promoters wanted to make a branch line to Portsmouth, but in those early days the cost of a direct route was impossibly daunting. The company renamed itself the London and South Western Railway, and instead built a branch line from Bishopstoke (Eastleigh) to Gosport, opening on 7 February 1842. Portsmouth could be reached from Gosport by ferry.[6]

The importance of Portsmouth attracted the rival London, Brighton and South Coast Railway]], which sponsored the construction of a route from Brighton to Portsmouth via Chichester. This opened on 14 June 1847. Portsmouth could now be reached from London via Brighton [37]

The LSWR had realised how unsatisfactory its approach to Portsmouth was, and made a connecting line from Fareham. Initially intending to build its own line to Portsmouth, it compromised and joined the LBSCR route from Brighton. The actual point of junction was on a spur near Cosham, and it was agreed that the line into Portsmouth from there would be jointly operated.[37] This still fell short of the expectations of Portsmouth people, as the choice was via Brighton, reversing there, or via Bishopstoke. A branch line from Woking to Guildford and Godalming had been opened, and now a line from Godalming to Havant, joining the LBSCR line there, was made. The LSWR route relied on running powers over the LBSCR route from Havant to Portcreek Junction. The LBSCR was very disputatious at this period, and there was an undignified stand-off at Havant before mature arrangements were agreed.[38]

The Portsmouth station was about a mile (about 1.5 km) from piers at which the Isle of Wight ferries might be boarded, and as the popularity of the Island developed, the inconvenient transfer through the streets became increasingly prominent. Alternative piers on Portsea Island were built, failing to overcome the problem.[39]

A Stokes Bay branch was opened on 6 April 1863, connecting from the Gosport line; it offered direct transfer at its own ferry pier; but it was accessible via Bishopstoke, incurring a roundabout rail journey from London. It was absorbed by the LSWR in 1871 and struggled on until 1915 when part of it ws requisitioned by the Admiralty.[40]

This issue of access to steamers was finally resolved in 1876, when the existing joint line at Portsmouth was extended to a Portsmouth Harbour station, where direct transfer was at last possible.[41]

Isle of Wight lines

In 1864 the Isle of Wight Railway was opened, starting out from a Ryde station on the south-east of the town: the terrain prevented a closer approach to the steamer berth.[42] As leisure traffic developed this became increasingly, objectionable, and the mitigation provided by the horse drawn street running trams of the Ryde Pier Company from 1871, requiring two transfers for onward travel, was hardly sufficient.

The LSWR and the LBSCR together built an extension line to the pier, and it opened to the Pier Head in 1880. It was not operated by the mainland companies, but by the Isle of Wight's own lines, which used it as an extension of their own routes. In 1923, all the Island lines, including this, transferred to the new Southern Railway as part of the Grouping process.[43][44]

Southsea Railway

An independent Southsea Railway was promoted, from Fratton station, serving Clarence Pier on the south side of Portsea Island. It opened on 1 July 1885, operated jointly by the LSWR and the LBSCR. The purported object of this short line was to alleviate the transfer to the ferries; by this time the through trains from London ran through to Portsmouth Harbour, so the benefit of changing trains to get to another pier was non-existent, and the Southsea Railway was a commercial failure. In an attempt to arrest the decline, railmotors were built to operate the line; these were reputedly the first in the United Kingdom. The line closed in 1914.[45][46]

Midhurst

The market town of Midhurst wished to secure a railway and the Petersfield Railway was formed to build a line. The LSWR absorbed the local company before construction was complete, and it opened as a simple branch of the LSWR on 1 September 1864.[47]

Lee on Solent

A landowner wished to develop an area on the coast west of Gosport, planning a high class watering place. A railway branch line was, he believed, essential, and he paid for one to be built, connecting with the Gosport branch. It opened in 1894, but it never had through trains on to the LSWR. It closed to passengers in 1931 and completely in 1935.[48]

Aldershot and Alton

The LSWR opened a line from Guildford to Farnham in 1849, extending to Alton in 1852. At the time the establishment of the army garrison at Aldershot led to a massive increase in population there, and consequently demand for travel, and the LSWR constructed a line from Pirbright Junction, on the main line near Brookwood, to a junction near Farnham via Aldershot. The new line opened in 1870. A curve was opened in 1879 at Aldershot Junctions enabling direct running from Guildford to Aldershot; the original line via Tongham declined as a result. The local network was electrified in 1937 and the Tongham line was closed to passengers at that time.[49][50][51]

Bentley and Bordon branch line

The Bordon Light Railway was constructed to serve large areas of military encampment around Bordon and Longmoor, and in the speculative hope of civilian residential development. It opened on 11 December 1905. The reduction in army manpower after 1945 led to a serious decline in use and the line was closed to passenger traffic from 16 September 1957, and completely in April 1966.[52]

Meon Valley line

In 1897 the LSWR applied to Parliament for authority to build a new main line railway between Alton and Knowle Junction, near Fareham. The line, which opened on 1 June 1903 was engineered for express trains and included the 1058-yard Privett Tunnel, the 539-yard West Meon Tunnel and the four-arch Meon Valley Viaduct. Although some through trains from London used the route,[53] the mainstay of the line's business was local passenger trains. On 7 February 1955 the passenger service ceased, followed by total closure in 1968.[54]

Mid Hants Line

The independent Mid-Hants Railway (MHR) opened its line between Alton and Winchester Junction, not far north of the city, on 2 October 1865.[55] The promoters had envisaged a first class main line to Southampton and Stokes Bay (for the Isle of Wight), rivalling the LSWR routes. The reality was that it was dependent on the LSWR to work it, and that as a single line with some prodigious gradients, it could not hope to compete.[56] From the outset, the MHR repeated complained that the services run by the LSWR were poorly timed and that the line's potential was not being fully realised. The MHR was taken over by the LSWR in 1884.[57] The line closed in 1973, but part of the route was adopted by the Watercress Line, a heritage railway organisation, which continues operations at present.[58]

Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway

The Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway was opened in 1901. The intervening terrain was very thinly populated, and it has been suggested by Kelly[59] and others that the line was built as a blocker for a proposed GWR line that would have entered LSWR territory. The line never made money and was closed to passengers in 1932, and completely 1937.[60][61]

Bishops Waltham

In 1863 the Bishop's Waltham Railway Company opened its branch line between Bishop's Waltham and the LSWR's Botley station on the Eastleigh to Fareham Line. The LSWR worked the branch line. It was never commercially successful and the LSWR took over the local company in 1881. It closed to passengers in 1932 and to goods in 1962.[62]

On to Dorchester and Weymouth

The Southampton and Dorchester Railway

The London and Southampton Railway promoters had lost the first battle for authorisation to make a line to Bristol, but the objective of opening up the country in the southwest and west of England remained prominent.[63] In fact it was an independent promoter, Charles Castleman, a solicitor of Wimborne Minster, who assembled support in the South West, and on 2 February 1844 proposed to the LSWR that a line might be built from Southampton to Dorchester: he was rebuffed by the LSWR, who were looking towards Exeter as their next objective.[64] Castleman went ahead and developed his scheme, but relations between his supporters and the LSWR were extremely tense, and Castleman formed a Southampton and Dorchester Railway, and negotiated with the Great Western Railway instead. The Bristol & Exeter Railway, a broad gauge company allied to the GWR, reached Exeter on 1 May 1844, and the GWR was promoting the Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway which was to connect the GWR to Weymouth. It seemed to the LSWR that on all sides they were losing territory in the west country that they considered rightfully theirs, and they hastily prepared plans for their own lines crossing from Bishopstoke to Taunton. Much was made of the roundabout route of the Southampton and Dorchester line, and it was mockingly referred to as Castleman's corkscrew or the water snake.[65]

The Five Kings (the Commission headed by Lord Dalhousie) published their decision, that most of the broad gauge lines should have preference, as well as the Southampton and Dorchester line which was to be built on the narrow gauge.[66] Formal agreement was reached on 16 January 1845 between the LSWR, the GWR and the Southampton & Dorchester, agreeing exclusive areas of influence for future railway construction as between the parties. The Southampton and Dorchester line was authorised on 21 July 1845;[67] there was to be an interchange station at Dorchester to transfer to the broad-gauge WS&W line, which was to be required to lay mixed gauge to Weymouth to give narrow gauge trains from Southampton access. To demonstrate impartiality the Southampton and Dorchester would be required to lay mixed gauge on its line for the same distance east of Dorchester, even though this did not lead to any source of traffic as there were no stations or goods sidings on the dual-gauge section. Interests in Southampton had also forced a clause in the Act requiring the S&DR to build a station at Blechynden Terrace, in central Southampton. This became the present day Southampton Central; the Southampton and Dorchester was to terminate at the original LSWR terminus in Southampton.[68]

The line opened on 1 June 1847 from a temporary station at Blechynden Terrace westwards, as the tunnel between there and the LSWR station at Southampton had suffered a partial collapse; that section was finally opened on the night of 5–6 August 1847, for a mail train.[69][70]

Powers were taken for the LSWR to amalgamate with the Southampton & Dorchester, and this took effect on 11 October 1848.[71]

The Southampton and Dorchester line ran from Brockenhurst in a northerly sweep through Ringwood and Wimborne, bypassing Bournemouth (which had not yet developed as an important town) and Poole; the port of Poole was served by a branch to Lower Hamworthy on the south side of Holes Bay. It then continued via Wareham to a terminus at Dorchester which was sited to facilitate a further extension in the direction of Exeter. The link to the WS&W line required through trains calling at Dorchester to reverse in and out of Dorchester station.[72]

Fawley branch

Local interests proposed a light railway in 1898; it was to run from a junction with the main line at Totton to Stone Point. A pier there was planned, to make a short crossing to the Isle of Wight. The promoters approached the LSWR for financial assistance, and a line to Fawley was confirmed by a Light Railway Order on 10 November 1903. However nothing was done and the powers lapsed. The light railway proposal was revived in 1921 with the backing of the Agwi Petroleum Co, which planned to erect a small oil refinery at Fawley. The £120,000 equity capital was partly funded by the LSWR. After some changes, the Southern Railway obtained an Order on 27 February 1923. The line was opened on 20 July 1925.[73]

The line closed to passenger services in 1966, but at present plans are being implemented to reopen the passenger operation.[74]

Christchurch and Bournemouth

The Southampton and Dorchester Railway opened its main line in 1847; it was routed via Ringwood, considered at the time to be more important then Bournemouth. As Bournemouth grew in importance, it was decided to build the Ringwood, Christchurch and Bournemouth Railway. It opened in 1862 between Ringwood and Christchurch.[75] Patronage was disappointing, but the line opened on to Bournemouth in 1870.[76] The Christchurch to Bournemouth section became part of the present-day main line, but the line from Ringwood to Christchurch closed in 1935.[77]

Lymington

The Lymington Railway Company opened a line from Brockenhurst on the Southampton and Dorchester Railway main line to what is now Lymington Town station in 1858. The line was worked by the LSWR, which abosorbed the smaller company in 1879. Lymington was important industrially at the time, and a ferry service to the Isle of Wight enhanced the business on the line. The jetty at Lymington was cramped and inconvenient for passenger transfer, and in 1884 a short extension, crossing Lymington River to a new Pier station, was opened. The line was electrified in 1967,[78] and continues in use at the present day.[79]

Swanage

The town of Swanage was bypassed by the Dorchester line, and local interests set about securing a branch line. After false starts this was achieved when the Swanage Railway Act got the Royal Assent in 1881 for a line from Worgret Junction, west of Wareham, to Swanage with an intermediate station at Corfe Castle. Wareham station had been a simple wayside structure, and a new interchange station was built west of the level crossing for the purposes of the branch. The line opened on 20 May 1885, and the LSWR acquired the company from 25 June 1886. Passenger traffic ended in 1972. It was taken over by a preservation society and the line reopened as a heritage railway in 1995.[80]

Portland

The Isle of Portland is formed of a very high quality stone much used for the construction of buildings. In 1865 the Weymouth and Portland Railway opened its line from Weymouth GWR station to Portland; it was worked jointly by the LSWR and the GWR.[81] The Easton and Church Hope Railway was incorporated soon afterwards to bring stone down to a new jetty, but the company failed to build its line. A modified route connecting to the Weymouth and Portland Railway was opened in 1900. The entire route Weymouth - Portland - Easton was worked jointly, and then later by the LSWR alone.[82] The line later declined, closing to passengers in 1952 and completely in 1965.[83]

West to Salisbury and Exeter

Salisbury

While Castleman was developing his Southampton and Dorchester line, the LSWR was planning to reach the important city of Salisbury. This was done by a branch from Bishopstoke by way of Romsey and the Dean Valley. By launching from Bishopstoke, the Company wished to connect the ports of Southampton and Portsmouth with Salisbury, but this made the route to London somewhat circuitous. The necessary Act was obtained on 4 July 1844, but land acquisition delays and inefficient contract arrangements delayed the opening until 27 January 1847, and then only for goods trains; passengers were conveyed from 1 March 1847. The Salisbury station was at Milford, on the east side of the city.

Business interests in Andover were disappointed that the Salisbury line was not to pass through their town, and a London to Salisbury and Yeovil line through Andover was being promoted; it might ally with a line from Yeovil to Exeter with a Dorchester branch, forming a new, competing London to Exeter line, so that the LSWR territorial agreement with the GWR would be worthless. When the LSWR indicated that they would themselves build a line from Salisbury to Exeter, the GWR complained bitterly that this broke the 16 January 1845 territorial agreement, and the Southampton and Dorchester complained too that this new line would abstract traffic from them. As the railway mania was now at its height, a frenzy of competing schemes was now proposed. The LSWR itself felt obliged to promote doubtful schemes in self-defence, but by 1848 the financial bubble of the mania had burst, and suddenly railway capital was difficult to find. In that year, only a few more realistic schemes gained Parliamentary authority: the Exeter, Yeovil and Dorchester Railway, for a narrow-gauge line from Exeter to Yeovil, and the Salisbury and Yeovil Railway.[10]

At the end of 1847, work had begun on the LSWR's own line from Basingstoke to Salisbury via Andover, and the scene seemed at last to be set for LSWR trains to reach Exeter. This apparent resolution of the conflict was deceptive, and in the following years a succession of disruptive pressures exerted themselves. The Southampton and Dorchester Railway insisted that it should be the route to Exeter via Bridport; the GWR and its allies were proposing new schemes intersecting the LSWR's route west; the Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth line resumed construction and appeared to threaten the LSWR's future traffic; the Andover Canal was to be converted to a broad gauge railway; and residents of towns on the proposed LSWR route were angry at the delay in actually providing the new line.

The outcome of all this was that the Salisbury and Yeovil Railway was authorised on 7 August 1854; the LSWR line from Basingstoke resumed construction, and was opened to Andover on 3 July 1854, but it took until 1 May 1857 for the line to open from there to Salisbury (Milford). The LSWR had given undertakings to extend to Exeter and it was compelled to honour these, obtaining the Act on 21 July 1856.[10]

To Exeter

After a long period of conflict, the LSWR's route to the West of England was clear; the earlier connection to Milford station at Salisbury from Bishopstoke had been opened on 17 January 1847. The route from London was shortened by the route from Basingstoke via Andover on 2 May 1859, with a more convenient station at Salisbury Fisherton Street. The conflict had centred around the best route to reach Devon and Cornwall, and this had finally been agreed to be the so-called "central route" via Yeovil. The Salisbury and Yeovil Railway opened its line, from Salisbury to Gillingham on 1 May 1859; from there to Sherborne on 7 May 1860, and finally to Yeovil Junction on 1 June 1860.[84]

The controversy over the route to Exeter having been resolved, the LSWR itself had obtained authority to extend from Yeovil to Exeter, and constructing it swiftly, it opened on 19 July 1860 to its Queen Street station there.[85]

Branches between Basingstoke and Exeter

From Basingstoke to Salisbury to be written.

The topography of the line from Salisbury to Exeter is such that the main line passed by many significant communities. Local communities were disappointed by the omission of their town from railway connection, and, in many cases encouraged by the LSWR, they promoted independent branch lines. These lines were worked, and sooner or later absorbed, by the LSWR, so that in time the main line had a series of connecting branches.

West of Salisbury there were branch lines to:

- Yeovil; the line ran from Yeovil Junction to Yeovil Town station;

- Chard; the branch opened on 8 May 1863, from Chard Road (later Chard Junction) to Chard Town;

- Lyme Regis; the branch line from Axminster to Lyme Regis opened on 24 August 1903;[86]

- Seaton; a branch line from Seaton Junction to Seaton opened on 16 March 1868;[87]

- Sidmouth and Exmouth; a line opened from Feniton, later Sidmouth Junction, to Sidmouth on 6 July 1874;[88] a branch was constructed from Tipton St Johns to Budleigh Salterton, opening on 15 May 1897, and extended from there to Exmouth, opening on 1 June 1903;[88]

- Exmouth; this branch opened from Exmouth Junction on 1 May 1861.[88]

Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway

The Somerset and Dorset Railway completed its line to Bath on 20 July 1874. The extension to Bath from its misconceived origin plunged it into debt from which it only recovered by leasing its line to the Midland Railway and the LSWR jointly. This was agreed on 1 November 1875.[89][90]

The line's trains ran from Broadstone (near Bournemouth, LSWR) and Wimborne to Bath and Burnham-on-Sea, with a branch to Wells (and from 1890 by lease, Bridgwater. At Templecombe the line made a spur connection to the LSWR station on the main line between Salisbury and Yeovil.[91]

The line retained a distinctive individuality, but it was difficult to operate, and ultimately unprofitable.[92]

West of Exeter

Exeter to Barnstaple

Local railways towards North Devon had already opened: the Exeter and Crediton Railway opened on 12 May 1851,[93] and the North Devon Railway from Crediton to Bideford opened on 1 August 1854. Both lines were constructed on the broad gauge. The LSWR acquired an interest in these lines in 1862–63 and then bought them in 1865. The Bristol and Exeter railway had reached Exeter at St Davids station on 1 May 1844[94] and the South Devon Railway had extended southwards in 1846.[95] The LSWR Queen Street station was high above St Davids station, and a westward extension required the line to descend and cross the other lines.

The LSWR built a connecting line that descended to St Davids station by a steep falling gradient of 1 in 37 (2.7%). The authorising Act required the Bristol and Exeter Railway to lay narrow gauge rails as far as Cowley Bridge Junction, a short distance north of St Davids where the North Devon line diverged. Under the terms of this concession, all LSWR passenger trains were required to make calls at St Davids station. LSWR trains to London ran southwards through St Davids station, while broad gauge trains to London ran northwards.

Plymouth

The North Devon line formed a convenient launching point for an independent LSWR line to Plymouth. The LSWR encouraged local interests, and the Devon and Cornwall Railway opened from Coleford Junction to North Tawton on 1 November 1865, and in stages from there to Lidford (later Lydford) on 12 October 1874. The LSWR obtained running powers over the South Devon and Launceston Railway, giving it access to Plymouth over that line.

Another nominally independent company, the Plymouth, Devonport and South Western Junction Railway built a line from Lidford to Devonport, and the LSWR leased and operated the line, gaining independent access to Devonport, and its own passenger terminal at Plymouth Friary.

Ocean liner services and sleeping cars

Beginning in April 1904, the LSWR operated a boat train service between Devonport Stonehouse Pool and Waterloo in connection with American Line transatlantic ocean liners, and from May 1907, liners of the White Star Line as well. On 30 June 1906, one of these trains, with five coaches carrying 48 passengers from the American liner New York, was wrecked in the Salisbury rail crash. The boat trains included restaurant cars, and in 1908, four sleeping cars were built at Eastleigh for the Plymouth boat trains. Each sleeping car had seven single-berth first-class compartments and two twin-berth third-class compartments. They did not last long: under an agreement made in May 1910 between the LSWR and GWR, passengers disembarking at Plymouth were carried to London on GWR services, and the LSWR boat trains from Plymouth were withdrawn. With the end of the ocean liner services, all four sleeping cars were sold to the GWR.[96][97][98]

Holsworthy and Bude

The line from Okehampton to Lydford itself provided a good starting point for a branch to Holsworthy, in northwest Devon, and this opened on 20 January 1879, and was extended to Bude in Cornwall on 10 August 1898.

North Cornwall

The line to Holsworthy itself provided a further starting point for a branch to what became the LSWR's most westerly point at Padstow, 260 miles (420 kilometres) from Waterloo). The line was promoted by the North Cornwall Railway, and opened in stages, finally being completed on 27 March 1899.

Electrification

In the early years of the twentieth century electric traction was adopted by a number of urban railways in the United States. The London and North Western Railway adopted a four-rail system and started operating electric trains to Richmond over the LSWR from Gunnersbury, and soon the Metropolitan District Railway was doing so as well. In the face of declining suburban passenger income, for some time the LSWR failed to respond, but in 1913 Herbert Walker was appointed chairman, and he soon implemented an electrification scheme in the LSWR suburban area.

A third rail system was used, with a line voltage of 600 V DC. The rolling stock consisted of 84 three-car units, all formed from converted steam stock, and the system was an immediate success when it opened in 1915–16. In fact, overcrowding was experienced in busy periods and trains were augmented by a number of two-car non driving trailer units from 1919, also converted from steam stock, which were formed between two of the three-car units, forming an eight-car train. All the electric trains provided first and third class accommodation only.

The routes electrified were in the inner suburban area—a second stage scheme had been prepared but was frustrated by the First World War—but extended as far as Claygate on the New Guildford line; this was operated at first as an interchange point, but the section was discontinued as an electrified route when overcrowding nearer London occurred, the electric stock being used there and the Claygate line reverting to steam operation.

Concomitant with the electrification, the route between Vauxhall and Nine Elms was widened to eight tracks, and a flyover for the Hampton Court branch line was constructed, opening for traffic on 4 July 1915.[16]

Southampton Docks

Origins

When the London and Southampton Railway was being constructed, it was realised that new business would be generated, and the dock facilities at Southampton needed to be extended. The Southampton Docks Company was created for that purpose in May 1836, with capital of £350,000. The area chosen was the town beach, at the confluence of the rivers Test and Itchen.[99][100]

Over the following two decades there was a constant process of building larger and deeper facilities as vessels in use were larger, more numerous, and in need of additional repair facilities. By 1858 £706,000 had been spent.[101]

In 1873 a further extension of the quay southwards down the river Itchen was undertaken, culminating in the formation of the Empress Dock between 1886 and 1890. The dock company was unable to raise the finance for the work, and obtained a loan of £250,000 from the London and South Western Railway. Southampton was able to take the largest vessels afloat at any state of the tide.[102]

Acquisition by the LSWR

In 1892 the Port of Southampton was the only port in the world able to take the deepest draught vessels at any state of the tide, but the Dock Company was not financially secure. The undertaking was purchased by the LSWR on 1 November 1892 for £1.36 million. The LSWR immediately started investing in further extensions and improvements to the dock.[102][100]

The Victoria (Royal) Pier was substantially enlarged in 1892 and lengthened to include a pavilion, tea rooms, and a bandstand. A railway from the terminus station served both the Quay and the pier.[103]

LSWR shipping services

The LSWR developed a considerable cross channel shipping business. As well as passenger ferries to the Isle of Wight (also from Portsmouth and Lymington) there was a substantial cargo business to French ports on the English Channel.

Development under the Southern Railway

At the end of the nineteenth century Southampton Corporation developed plans to make new dock facilities in the West Bay, but they were hampered by inability to raise finance, and the LSWR took up the project. When the Southern Railway was formed in 1923, the Chairman Sir Herbert Walker planned the West Docks. Over 400 acres of tidal mud was reclaimed, providing new quays about 1+1⁄2 miles in extent, and a new, larger dry dock, and shore facilities; the berths opened progressively from 1934 onwards. A new railway was opened from the West (Southampton Central) station to a train ferry jetty near the Royal Pier.[104]

By 1926 the Southern Railway Company had sailings to the Channel Islands, as well as Saint Malo, Caen, Cherbourg and Honfleur. In 1931 the banana ships of Elders & Fyffes started running from the West Indies.[105]

Railway activity

When the LSWR acquired the Dock Company, it replaced the industrial locomotive fleet with fourteen class B4 dock locomotives of its own, purpose-built for the dock work. In 1947 the Southern Railway acquired a fleet of locomotives built for war use by the US Corps of Transportation.[106]

The volume of railway traffic handled at the docks was prodigious. In addition to the boat trains, banana specials were particularly memorable. In 1871 a total of 2362 ships called at the docks, and well over 500 waggons per week were used in transporting goods; a further 3483 waggons of coal also arrived that year to fuel vessels, most of which were steam ships. In addition 10,000 trucks of mail arrived; these totals had practically doubled 2 years later.[106]

Over the Friday and Saturday of the August bank holiday weekend of 1932, 78 boat trains were handled in 48 hours. On a single day in June 1933 a total of 976 goods wagons left the docks during a 19-hour period, 424 of these being loaded with bananas. In 1936 the dock railways operated 4,800 passenger and 4,245 goods trains.[106]

Eastleigh Works

In 1891, the works at Eastleigh, in Hampshire, were opened with the transfer of the carriage and wagon works from Nine Elms in London. The locomotive works were transferred from Nine Elms under Drummond, opening in 1909.

Notable people

Notable people connected with the LSWR include:

Chairmen of the board of directors[107]

- 1832–1833: Sir Thomas Baring, 2nd Baronet

- 1834–1836: John Wright

- 1837–1840: Sir John Easthope, 1st Baronet

- 1841–1842: Robert Garnet

- 1843–1852: William Chaplin

- 1853: Francis Scott

- 1854: Sir William Heathcote

- 1854–1858: William Chaplin (again)

- 1859–1872: Captain Charles Mangles

- 1873–1874: Charles Castleman

- 1875–1892: Ralph H. Dutton

- 1892–1899: Wyndham S. Portal

- 1899–1904: Lt. Col. the Hon. H. W. Campbell

- 1904–1910: Sir Charles Scotter

- 1911–1922: Sir Hugh Drummond

General managers[107]

- 1839–1852: Cornelius Stovin (as traffic manager)

- 1852–1885: Archibald Scott (as traffic manager 1852–1870)

- 1885–1898: Sir Charles Scotter

- 1898–1912: Sir Charles Owens

- 1912–1922: Sir Herbert Walker

Resident engineers[108]

- 1837–1849: Albinus [Albino] Martin

- 1849–1853: John Bass

- 1853–1870: John Strapp

- 1870–1887: William Jacomb (1832–1887)

- 1887–1901: E. Andrews

- 1901–1914: J. W. Jacomb-Hood

- 1914–1922: Alfred Weeks Szlumper[109]

Consulting engineers

- 1834–1837: Francis Giles[110][111]

- 1837–1849: Joseph Locke[111][112]

- 1849–1862: John Edward Errington[112]

- 1862–1907: W. R. Galbraith[113]

Mechanical engineers[107]

- 1838–1840: Joseph Woods (as Locomotive Superintendent)

- 1841–1850: John Viret Gooch (as Locomotive Superintendent)

- 1850–1871: Joseph Hamilton Beattie (as Locomotive Superintendent)

- 1871–1877: William George Beattie (as Locomotive Superintendent)

- 1877–1895: William Adams (as Locomotive Superintendent)

- 1895–1912: Dugald Drummond (as Chief Mechanical Engineer from 1904)

- 1912–1922: Robert Urie (as Locomotive Engineer)

Locomotive liveries

Liveries for painting of locomotives adopted by the successive Mechanical Engineers:

- To 1850 (John Viret Gooch)

Little information is available although from 1844 dark green with red and white lining, black wheels and red buffer beams seems to have become standard.

- 1850–1866 (Joseph Hamilton Beattie)

- Passenger classes – Indian red with black panelling inside white. Driving splashers and cylinders lined white. Black wheels, smokebox and chimney. Vermilion buffer beams and buff footplate interior.

- Goods classes – unlined Indian red. Older engines painted black until 1859.

- 1866–1872 (Joseph Hamilton Beattie)

- All engines dark chocolate brown with 1-inch (25 mm) black bands edged internally in white and externally by vermilion. Tender sides divided into three panels.

- 1872–1878 (William George Beattie)

- Paler chocolate (known as purple brown) with the same lining. From 1874 the white lining was replaced by yellow ochre and the vermilion by crimson.

- 1878–1885 (William Adams)

- Umber brown with a 1-inch (25 mm) black band externally and bright green line internally. Boiler bands black with white edging. Buffer beams vermilion. Smokebox, chimney, frames etc. black.

- 1885–1895 (William Adams)

- Passenger classes – pea green with black borders edged with a fine white line. Boiler bands black with a fine white line to either side.

- Goods classes – holly green with black borders edged by a fine bright green line.

- 1895–1914 (Dugald Drummond)

- Passenger classes – royal mint green lined in chocolate, triple lined in white, black and white. Boiler bands black lined in white with 3-inch (76 mm) tan stripes to either side. Outside cylinders with black borders and white lining. Smokebox, chimney, exterior frames, tops of splashers, platform etc. black. Inside of the main frames tan. Buffer beams vermilion and cab interiors grained pine.

- Goods classes – holly green edged in black and lined in light green. Boiler bands black edged in light green.

- 1914–1917 (Robert Urie)

- Passenger classes – olive green with Drummond lining.

- Goods classes – holly green with black edging and white lining.

- 1917–1922 (Robert Urie)

- Passenger classes – olive green with a black border and white edging.

- Goods classes – holly green often without lining until 1918.

Accidents and incidents

- On 11 September 1880, a light engine was waiting at Nine Elms Locomotive Junction on the Down Main Line; it was to move into the locomotive depot. Seven persons were killed. There was a changeover of signalling staff, and the engine was forgotten. A down passenger train was accepted by the signalman and the train ran into the light engine.[114]

- On 6 August 1888, a light engine and a passenger train were in a head-on collision at Hampton Wick station. Four people were killed and fifteen were injured. The light engine was started away from Kingston by hand signal, and the signalman there had failed to set the points for the correct line; the engine was running on the wrong line.[115]

- On 1 July 1906, an Up Boat Train Express passenger train was derailed at Salisbury due to excessive speed on a curve. A 30 mph (48 km/h) speed restriction applied to the curve at the east end of the station. Twenty-eight persons were killed and eleven were injured. The driver appeared not to react to the proximity of the speed restriction, yet he was a total abstainer and there were no other explanatory factors, either human or mechanical.[116]

Salisbury

Salisbury

Other details

- Disregarding the Waterloo & City line, the longest tunnel is Honiton Tunnel 1,353 yards (1,237 m); there were six others longer than 500 yards (457 m)

- The anglicised script version of the Russian word for railway station is 'vokzal'. A longstanding legend has it that a party from Russia planning their own railway system arrived in London around the time that the LSWR's Vauxhall station was opened. They saw the station nameboards, thought the word was the English word for railway station and took it back home. In fact, the first Russian railway station was built on the site of pleasure gardens based on those at Vauxhall – nothing to do with the English railway station. (Fuller details are in the Vauxhall article.)

Notes

References

- Williams 1968, p. 36

- Williams 1968, p. 40

- Williams 1968, p. 38

- Williams 1968, pp. 51–53

- David Gary, Going Over the Water: Memories of the Gosport Ferry, Chaplin Books, Gosport, 2017, ISBN 978-1-911105-25-1, section 1

- Williams 1968, pp. 121–123

- Edwin Course, Gosport's Most Private Station, Gosport Records No 5, pages 11 to 17, 1972, The Gosport Society

- Peter J Keat, Rails to the Yards, Gosport Railway Society, 1992 fourth impression 2012, ASIN B00BE2TS2O, Kindle book not paginated

- Marden 2011, p. 43.

- Williams (1968), chapter 3

- R H G Thomas, The London and Greenwich Railway, B T Batsford Ltd, London, 1972, ISBN 0-7134-0468-X, pages 50 and 51

- Williams 1968, pp. 36, 167, 168, 222 and 223

- Jackson 1999b, p. 42.

- Raymond South, Crown, College and Railways: How the Railways Came to Windsor, Barracuda Books Limited, Buckingham, 1978, ISBN 0-86023-071-6, pages 39 to 41

- Williams 1968, p. 175

- Jackson 1999a, pp. 180–183.

- White 1987, p. 63.

- Jackson 1999a, pp. 161–163.

- Gillham 2001, pp. 7–11

- Lordan 2021, p. 29.

- Williams 1968, pp. 160, 161 163 and 165

- Gillham 2001, pp. 209–222

- Lordan 2021, p. 34.

- David Brandon and Alan Brooke, London: City of the Dead, History Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7509-4633-9, Kindle book not paginated

- Course 1976, pp. 129–130.

- Lordan 2021, p. 67-68.

- Williams 1973, pp. 14–16

- Gillham 2001, pp. 8–11

- Gray, LCDR, pages 69 to 71

- Jackson 1999a, pp. 220–221, 225–226.

- Williams 1973, pp. 18–19

- Williams 1973, p. 38

- Jackson 1999a, pp. 98–99.

- Williams 1973, p. 20

- Gillham 2001, p. 41

- Gillham 2001, pp. 5, 84

- J T Howard Turner, The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, volume 1: Origins and Formation, B T Batsford Ltd, London, 1977, ISBN 0 7134 0275 X, page 237

- Williams 1968, pp. 145–146.

- Williams, volume 2, pages 111 to 114

- Kevin Robertson, The Railways of Gosport, Noodle Books, Southampton, 2009, ISBN 978 1 906419 25 7, pages 15 to 18

- Williams 1973, p. 114.

- Maycock & Silsbury 1999, p. 29.

- Williams 1973, pp. 127–128.

- Maycock & Silsbury 1999, pp. 92–93.

- Kevin Robertson, The Southsea Railway, Kingfisher Railway, Productions, Southampton, Kingfisher, 1985, ISBN 0-946184-16-X, pages 3, 5, 25 and 27

- O J Morris and E R Lacey, The Southsea Railway, in the Railway Magazine, June 1931, pages 455 to 458

- Peter A Harding, The Petersfield to Midhurst Branch Line, self-published by Peter Harding, Woking, 2013, ISBN 978 0 9552403 8 6, pages 8 and 9

- Kevin Robertson, The Railways of Gosport, Including the Stokes Bay and Lee-on-the-Solent Branches, Noodle Books, Southampton, 2009, ISBN 978-1-906419-25-7, pages 25 and 26

- Williams 1968, pp. 183–186

- J Spencer Gilks, Railway Development at Aldershot, in Railway Magazine, March 1956, pages 188 to 193

- David Brown, Southern Electric, volume 2, Capital Transport Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1-85414-340-2, pages 23 and 27

- Maggs 2010, pp. 111, 114.

- Maggs 2010, p. 99.

- Maggs 2010, pp. 102, 104.

- Hardingham 1995, p. 40.

- Hardingham 1995, pp. 7–11.

- Hardingham 1995, pp. 42–43.

- Hardingham 1995, p. 111.

- Arthur Kelly, The Basingstoke and Alton Light Railway, in the Railway Magazine, October 1900, pages 326 to 332

- Martin Dean, Kevin Robertson, and Roger Simmonds, , The Basingstoke & Alton Light Railway, Southampton 2003, ISBN 0-9545617-0-8, pages 39, 45 and 81

- Donald J Grant, Directory of the Railway Companies of Great Britain, Matador, Kibworth Beauchamp, 2017, ISBN 978 1785893 537, pages 33 and 34

- Roger Simmonds and Kevin Robertson, The Bishop's Waltham Branch, Wild Swan Publications Ltd, Didcot, 1988, ISBN 0-906867-67-3, pages 5, 12 and 79

- B L Jackson, Castleman's Corkscrew: volume 1: the Nineteenth Century, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2007, ISBN 978-0-85361-666-5, pages 17 and 18

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, pages 18, 19, 28 and 29

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, pages 14 and 30

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, page 33

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, page 38

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, page 36

- Castleman's corkscrew, volume 1, page 54

- John Bosham, The London and South Western Railway's Route to Weymouth, in the Railway Magazine, March 1903, pages 219 to 229

- Castleman's Corkscrew, volume 1, page 74

- Colin G Maggs, Dorset Railways, Dorset Books, Wellington, 2009, ISBN 978-1-871164-66-4, page 17

- Faulkner & Williams 1988, pp. 135–136

- Waterside Reopening Proposal at https://www.networkrail.co.uk/running-the-railway/our-routes/wessex/the-waterside-line/

- B L Jackson, Castleman's Corkscrew: volume 1: the Nineteenth Century, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2007, ISBN 978-0-85361-666-5, page 127

- Jackson, Corkscrew, volume 1, page 133

- Jackson 2008, pp. 90–91.

- Gillham 2001, p. 118

- Peter Paye, The Lymington Branch, Oakwood Press, Tarrant Hinton, 1979, pages 7, 9, 11 and 12

- Colin G Maggs, Dorset Railways, Dorset Books, Wellington, 2009, ISBN 978-1-871164-66-4, pages 45 to 49

- B L Jackson, Isle of Portland Railways: volume 2: the Weymouth and Portland Railway, the Easton and Church Hope Railway, Oakwood Press, Usk, 2000, ISBN 0-85361-551-9, pages 25 to 27

- Jackson, Isle of Portland, volume 2, pages 57 to 61

- Jackson, Portland Lines, volume 2, pages 207, 209 and 218

- Ruegg 1960, pp. 44–45, 48.

- Thomas 1988, p. 55.

- Mitchell & Smith 1987, Historical background.

- Phillips 2000, p. 111.

- Mitchell & Smith 1992, Historical background.

- Atthill 1985, pp. 55–59.

- MacDermot & Clinker 1964b, pp. 96–99.

- Atthill 1985, pp. 41–45, 70.

- Atthill 1985, p. 152.

- MacDermot & Clinker 1964b, p. 81.

- MacDermot & Clinker 1964a, p. 92.

- MacDermot & Clinker 1964a, p. 156.

- Faulkner & Williams 1988, pp. 162–4, 173.

- Weddell 2001, pp. 142, 145, 217.

- Rolt & Kichenside 1982, p. 166.

- Dave Marden, The Building of Southampton Docks, Derby Books Publishing Company, Derby, 2012, ISBN 978-1-78091-062-8, page 10

- Mike Roussel, The story of Southampton Docks, Breydon Books Publishing Company, Derby, 2009, ISBN 978-1-85983-707-8, page 9 and 10

- Marden, pages 21 to 26

- Marden, pages 32, 33 and 37

- Marden, page 73

- Marden pages 75 and 103

- Roussel, pages 35 and 36

- Marden, pages 176 to 181

- Ellis 1956, Appendix B.

- Williams 1973, pp. 302–303.

- Marshall 1978, p. 213.

- Williams 1968, p. 21.

- Williams 1968, pp. 29–31.

- Williams 1968, p. 77.

- Marshall 1978, pp. 89–90.

- F A Marindin, Collision which occurred on 11th September 1880 at the Locomotive Junction, Nine Elms, Board of Trade, 13 October 1880

- Mahor F A Marindin, Collision at Hampton Wick on 6th August 1888, Board of Trade, 31 August 1888

- J W Pringle, Accident to a Passenger Train at Salisbury on 1st July 1906, Board of Trade

Sources

- Atthill, Robin (1985). The Somerset and Dorset Railway (2nd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8692-1.

- Course, Course (1976). The Railways of Southern England: Independent and Light Railways. London: B T Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-3196-2.

- Ellis, C. Hamilton (1956). South Western Railway: Its mechanical history and background (1838-1922). Allen and Unwin.

- Faulkner, J. N.; Williams, R. A. (1988). The LSWR in the Twentieth Century. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8927-0.

- Gillham, J. C. (2001). The Waterloo & City Railway. Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-8536-1525-X.

- Hardingham, Roger (1995). The Mid Hants Railway: From construction to closure. Cheltenham: Runpast Publishing. ISBN 978-1870754293.

- Jackson, Alan A. (1999a). London's Local Railways (2nd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7479-6.

- Jackson, Alan A. (1999b). The Railway in Surrey. Penryn: Atlantic Transport Publishers. ISBN 0-906899-90-7.

- Jackson, B. L. (2008). Castleman's Corkscrew. Vol. 2. Cranborne: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8536-1686-3.

- Lordan, Robert (2021). Waterloo Station: A history of London's busiest terminus. Marlborough: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-78500-869-6.

- MacDermot, E. T.; Clinker, C. R. (1964a). History of the Great Western Railway. Vol. I: 1833–1863. London: Ian Allan.

- MacDermot, E. T.; Clinker, C. R. (1964b). History of the Great Western Railway. Vol. II: 1863–1921. London: Ian Allan.

- Maggs, Colin G. (2010). The Branch Lines of Hampshire. Stroud: Amberley Books. ISBN 978-1-8486-8343-3.

- Marden, Dave (2011). The Hidden Railways of Portsmouth and Gosport. Southampton: Kestrel Railway Books. ISBN 978-1-905505-22-7.

- Marshall, John (1978). A biographical dictionary of railway engineers. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7489-3.

- Maycock, R. J.; Silsbury, R. (1999). The Isle of Wight Railway. Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-544-6.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1987). Branch Line to Lyme Regis. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-9065-2045-2.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1992). Branch Lines to Exmouth. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 1-8737-9300-6.

- Phillips, Derek (2000). From Salisbury to Exeter: The Branch Lines. Shepperton: Oxford Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8609-3546-9.

- Rolt, L.T.C.; Kichenside, Geoffrey M. (1982) [1955]. Red for Danger (4th ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8362-0.

- Roussel, Mike (2009). The story of Southampton Docks. Derby: Breydon Books Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-8598-3707-8.

- Ruegg, Louis H. (1960) [1878]. The History of a Railway: The Salisbury and Yeovil Railway: A Centenary Reprint. Dawlish: David Charles.

- Thomas, David St John (1988). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 1: The West Country (6th ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-946537-17-8.

- Weddell, G.R. (March 2001). LSWR Carriages in the 20th Century. Hersham: Oxford Publishing Co. ISBN 0-86093-555-8. 0103/A1.

- White, H. P. (1987). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 3: Greater London (3rd ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-946537-39-9.

- Williams, R. A. (1968). The London & South Western Railway. Vol. 1: The Formative Years. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4188-X.

- Williams, R. A. (1973). The London & South Western Railway. Vol. 2: Growth and Consolidation. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5940-1.

Further reading

- Dendy-Marshall, C. F. (1968). Kidner, R.W. (ed.). A history of the Southern Railway. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0059-X. new ed.

- Nock, O. S. (1971). The London & South Western Railway. Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0267-3.

- Whishaw, Francis (1842). The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland Practically Described and Illustrated (2nd ed.). London: John Weale. pp. 292–301. OCLC 833076248.

External links

- www.lswr.org – South Western Circle: The Historical Society for the London & South Western Railway